Epidemics create a kind of history from below:

they can be world-changing, but the participants are almost inevitably ordinary folk, following their established routines, not thinking for a second about how their actions will be recorded for posterity. And of course, if they do recognize that they are living through a historical crisis, it’s often too late—because, like it or not, the primary way that ordinary people create this distinct genre of history is by dying.

—Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map

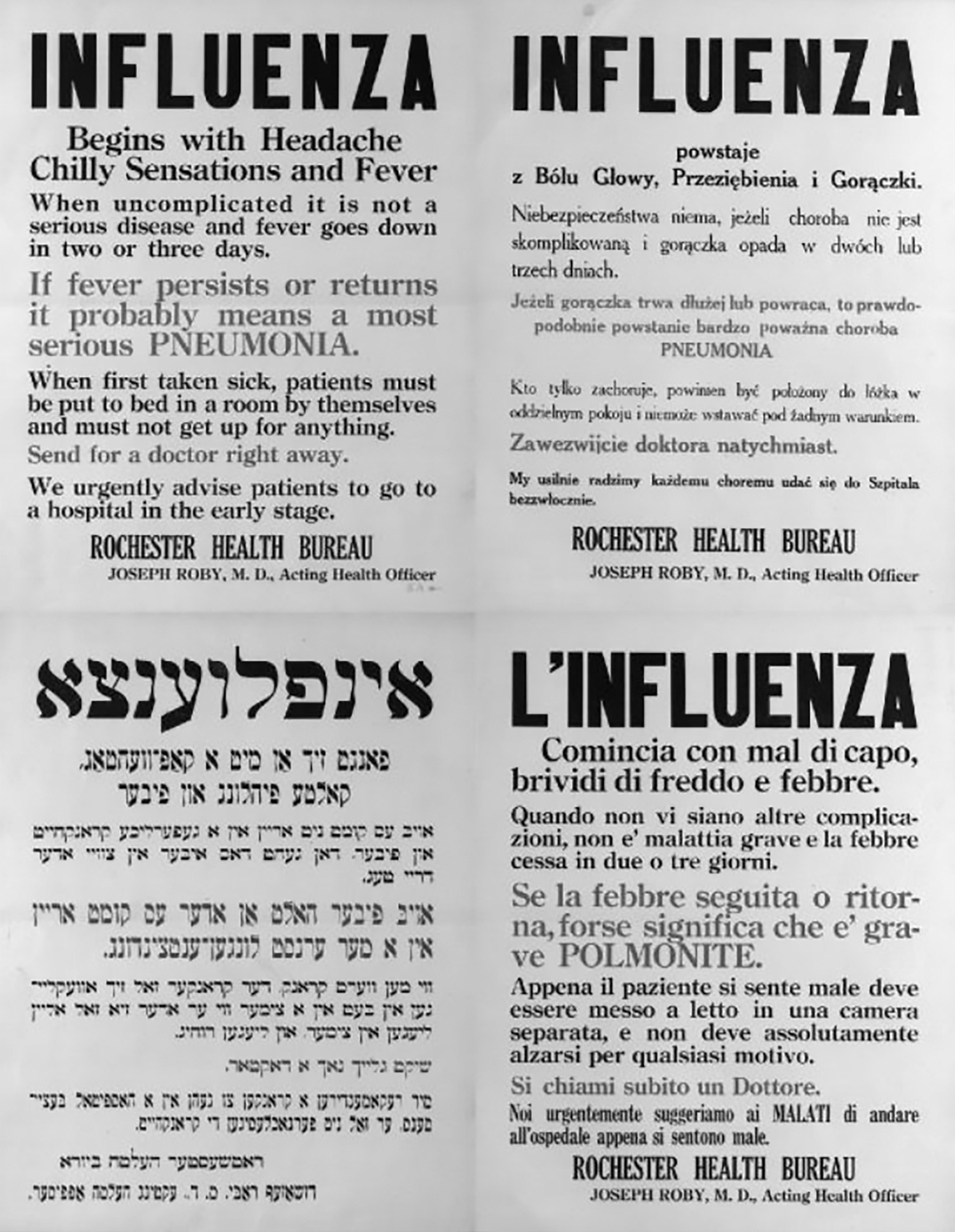

The Health Department in Rochester, New York, produced flu warning posters in four languages. [Rochester Public Library]

IT WAS 1950. The horrors of the First World War were distant memories, displaced by the calamities of World War II and the Holocaust. In America’s heartland, Johan Hultin, a twenty-five-year-old researcher from Sweden, was studying at the University of Iowa when he had a chance conversation over lunch. Hultin was focused on influenza viruses and had been interested in the 1918 flu pandemic for years.

By this time, scientists had begun to unlock the secret of influenza. In the early 1930s, they proved it was caused by a virus, not the bacteria many had blamed during the pandemic. Experimental vaccines began to be developed. Through the 1940s, different strains of the virus were found, showing it could quickly mutate, changing its genetic makeup. In 1944, the U.S. Army started giving flu shots to all its soldiers. In a process still used today, the flu shots were made from viruses grown in chicken eggs, then killed so that they could not cause infection. The dead virus triggers the body’s immune system response without actually making the person sick.

The lunchtime conversation with a visiting scientist from a well-known laboratory had piqued Hultin’s interest. The key to unlocking the still hidden secrets of the 1918 Spanish flu, the scientist suggested, might lie with bodies buried in an Arctic region where the permanently frozen ground might keep the viruses intact. Intrigued, Hultin later hit on the idea of going to Alaska to find bodies of flu victims that might be buried in the permafrost.

Lacking both funding and serious scientific equipment, Hultin became obsessed with his quest. When he learned of the place called Brevig Mission, he traveled there in 1951 and discovered the graves of the village’s victims, marked by a pair of crosses. Following a hunch, Hultin spoke with some of the village elders about his search for an answer to the Purple Death, and he was given permission to dig.

The man who traveled to Alaska in search of the Spanish flu virus, Johan Hultin was later called the “Indiana Jones of the scientific set.” [Kim Komenich, San Francisco Chronicle]

“This was a great adventure for a little boy from Sweden,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle in a 2001 interview. “I had never spoken to Eskimos before. I thought I was going to find the virus alive, I really did.”

After the catastrophe hit Brevig Mission, few survivors were left to bury the dead. Fewer still wanted to go near the bodies. Eventually, Alaskan territorial officials hired gold miners from Nome to bury the remains of flu victims in 1919. Using steam machinery, they melted a hole twelve feet wide, twenty-five feet long, and about six feet deep in the frozen ground.

Now in 1951, the bodies remained encased in the frozen soil. Working alone at first with only a pickax and shovel, Hultin built a fire to thaw the rock-hard ground, shoveled off the melted soil, then repeated the process. “It took two days to reach the first body,” he later recalled.

Two scientists from the University of Iowa and a paleontologist from the university in Fairbanks joined Hultin. Wearing only surgical masks and gloves, they had little protection against the virus if it should somehow still be “live.” Using the picks for two more days, the men reached four more bodies.

“In 1951, I was a graduate student,” Hultin later explained to journalist Gina Kolata. “I just didn’t have enough knowledge of how things spread.… We took precautions that were standard at the time, but we were not afraid of getting infected.”

Working with the remains of the flu victims, Hultin used rib cutters—instruments that look like pruning shears—to remove the chest plates and expose the lungs of the frozen corpses. Then he snipped some of the tissue from the lungs.

“We probably had a two-inch cube from each lung. The reason we didn’t do more was that we had a limited number of specimen containers.” The effort was decidedly low-tech and improvised. Using sterilized screw-cap jars, Hultin managed to get the lung tissue samples back to a lab in Iowa City. Without proper refrigeration equipment, he had preserved the tissue samples with dry ice removed from fire extinguishers. Back in the Iowa laboratory, however, using what would now be considered primitive techniques, Hultin failed to produce any live virus.

More than forty years later, in March 1997, fate struck again. Having retired as a pathologist, Johan Hultin happened to come across an article in Science magazine about other scientists seeking the answer to the Spanish flu mystery. One of these researchers, Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger, had discovered Spanish flu virus in tissue samples from 1918—a tiny bit of lung tissue that had been kept in storage by the U.S. Army. During the 1918 pandemic, doctors in the army camps had performed autopsies and collected tiny samples of lung tissue. A doctor in Fort Riley in Kansas—site of the initial outbreak in March 1918—had dutifully preserved the lung tissue in paraffin wax and sent it to Washington, D.C., where it lay in storage for nearly eighty years. “It was like Raiders of the Lost Ark,” Taubenberger later said. “We found the Ark of the Covenant.”

Reviving his quest, Hultin contacted Taubenberger and volunteered to go back to Alaska. Using his own savings, the seventy-two-year-old Hultin struck out for Brevig Mission once more in August 1997. The tissue samples from 1951 were by now useless. He would need to find new samples. On this solitary expedition, the veteran pathologist carried a pair of garden clippers borrowed, without permission, from his wife.

At about the same time, another research team was attempting to find the remains of the virus in the bodies of miners buried on a Norwegian island. That attempt failed when they discovered the ground in which the bodies were buried had thawed and refrozen repeatedly over the years.

As he had done in 1951, Johan Hultin appealed to the villagers for permission to open the graves. Again, Hultin explained his mission to the people, including the niece of a 1918 victim. “I said that a terrible thing had happened in November 1918 and I am here to ask permission to go back to the grave for a second time,” Hultin later recalled. “Science has now moved to the point where it is possible to analyze a dead virus and through that make a vaccine so that when it comes again, all of you can be immunized against it. There shouldn’t be any more mass deaths.”

With the agreement of local leaders and help from four young men of the village, Hultin opened the mass grave once more and found the body of a large woman who had died in the Spanish flu epidemic.

Hultin named the woman Lucy, taking his inspiration from the discovery of an ancient skeleton found in Ethiopia in 1974 that shed light on human evolution. The corpse’s thick layers of fat kept the woman’s lungs well preserved in the permafrost.

Using his wife’s pruning shears, Hultin opened Lucy’s mummified rib cage. He found two frozen lungs—the tissue he needed—and both were still full of blood. He removed the lungs, sliced them with an autopsy knife, and placed them in preserving fluid provided by Dr. Taubenberger.

Then he and the village helpers replaced the graveyard sod. Noticing that the grave markers from 1951 were gone, Hultin went to a nearby woodshop and built two new crosses. Carefully documenting the names of the seventy-two Brevig flu victims, Hultin later paid for brass plaques honoring the people whose deaths might now help unlock the secret of the Spanish flu. The plaques were attached to the crosses he had made.

With the samples Hultin had collected and sent on, a breakthrough moment was at hand. But it was not going to be an overnight solution. Using far more sophisticated techniques than had been available in 1951, including more advanced understanding of genetics and the ability to “map” genes, the secret of the Spanish flu virus was about to be unlocked.

Years of painstaking work led to a development that was a little like something out of Jurassic Park. Jeffery Taubenberger, medical technician Ann Reid, and their colleagues finally reconstructed the 1918 Spanish flu virus in 2005. Working with Hultin’s samples, the 1918 lung samples from Camp Funston preserved in paraffin, and another sample of the virus from the Royal London Hospital, Taubenberger and his colleagues actually re-created the virus in a secure lab at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These researchers used it to infect mice and human lung cells that had been grown in lab dishes. “For the first time in history,” writes science journalist Gina Kolata, “a long-extinct virus had been resurrected.”

One of the mysteries of the Spanish flu was solved: it was an avian strain of influenza, a virus carried by birds, which had jumped directly to humans.

“When a pathogen [a microorganism that can cause disease] leaps from some nonhuman animal into a person … sometimes causing illness or death, the result is a zoonosis,” science writer David Quammen explains. “It’s a mildly technical term … but it helps clarify the biological complexities behind the ominous headlines about swine flu, bird flu, SARS, emerging diseases in general, and the threat of a global pandemic. It helps us comprehend why medical science and public health campaigns have been able to conquer some horrific diseases, such as smallpox and polio, but unable to conquer other horrific diseases, such as dengue and yellow fever.… Ebola is a zoonosis. So is bubonic plague. So was the so-called Spanish influenza of 1918–1919.”

Besides isolating, identifying, and re-creating the Spanish flu virus, there were still large questions to be answered: Why was the virus so deadly? Why did it strike the young and healthy? And where did it really come from?

There are several possible explanations for the high mortality rate of the 1918 influenza pandemic. One is that a mutation of this particular virus had made the Spanish flu particularly aggressive. Viruses are in a constant state of mutation, as they exist only to find hosts in which they can reproduce. These alterations in the influenza virus mean a new flu vaccine is required each year to respond to the changes. As Jeffery Taubenberger writes, “It is unclear what gave the 1918 virus this unusual ability to generate repeated waves of illness. Perhaps the surface proteins of the virus drifted more rapidly than other influenza virus strains, or perhaps the virus had an unusually effective mechanism for evading the human immune system.”

The most obvious factor is that wartime circumstances alone contributed to the extraordinarily high death toll. Malnutrition, overcrowding in army and refugee camps, hospitals, and poor hygiene all combined to create large groups highly susceptible to the flu and far less able to fight it off.

That doesn’t explain why the Spanish flu was so strangely fatal to younger people. “Influenza and pneumonia death rates for 15-to-34-year-olds,” Taubenberger explains, “were more than twenty times higher in 1918 than in previous years.”

It may have to do with the power of the immune system. Younger, healthier people tend to have stronger immune systems. The immune system is the body’s response to any sort of danger. It is now thought that the powerful immune reactions of young adults were simply too strong. Part of their immune response was to send body fluids, including blood, to the lungs to attack or dislodge the invading virus. As the immune systems of young people aggressively responded to the virus, large amounts of bloody fluid flooded the lungs. Younger people, including many soldiers, were drowning in their own bodily fluids—the cause of the cyanosis that turned victims blue—the direct cause of the deaths of so many flu victims. The weaker immune systems of children and middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths among those groups.

This idea was tested in monkeys infected with the virus in 2007. The virus quickly spread and set off a powerful immune system response, moving faster than a normal flu virus and filling their lungs with blood and other fluids. The same thing may have happened to healthy humans in 1918. “Essentially people are drowned by themselves,” said one of the researchers in the monkey experiment.

There is another theory that explains the high mortality rates in 1918 and 1919. Perhaps the Spanish flu virus was not brand-new in 1918 but had existed before in a slightly weaker form. Some people may have already been affected by a strain of this flu virus and had developed the necessary antibodies—a protein produced by the immune system to fight viruses—to fend off the Spanish flu.

The question of the Spanish flu’s geographical origin still remains a mystery. If the Spanish flu existed before 1918, it could have originated in several places before exploding in Haskell County, Kansas, in March 1918. There had been earlier outbreaks of a similar flu in China and France. But lacking tissue samples from anyone in those areas, this remains an unsolved question. One theory is that the virus responsible for the Spanish flu was carried by wild aquatic birds. After passing through domesticated animals, such as ducks, it eventually made the leap to humans—perhaps through an open wound or small cut on someone handling infected bird meat or through consuming infected poultry.

* * *

AS THE SPANISH FLU epidemic wound down, the scientists who had struggled to understand it were brought up short. Dr. Victor Vaughan was one of the leading medical authorities of the time. He had seen the carnage of the pandemic in its early days at Camp Devens in the autumn of 1918. After the Spanish flu pandemic began to recede, he said, “Never again allow me to say that medical science is on the verge of conquering disease.… Doctors know no more about this flu than 14th century Florentine doctors had known about the Black Death.”

While some mysteries of the Spanish flu are still being explored, the consequences of the pandemic were profound in America and around the world.

The New Testament book of Revelation describes the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, whose arrival signals widespread disaster and destruction for humanity. Following World War I, two of these biblical Four Horsemen—War and Disease—had completed a hard ride over the world’s landscape. The life expectancy in America, which had been rising for decades, suddenly fell in 1918 from fifty-one years to thirty-nine years, dropping by an astonishing twelve years. The year 1918 also showed a very rare decline in the American population. Hundreds of thousands of children had been orphaned and whole families wiped out. Besides the unthinkable human toll, businesses had been destroyed and fortunes lost in the death and destruction.

After the twin horrors of world war and the Spanish flu, many Americans longed for a return to normalcy—a word used by President Warren G. Harding in his successful 1920 campaign for the presidency. It may be one of the reasons that very few people wrote or talked about the Spanish flu and that it largely disappeared from public memory—becoming a piece of hidden history.

Cover of sheet music for the popular song “How ’Ya Gonna Keep ’Em Down on the Farm.” [Wikimedia]

In many ways, America turned inward again. The horrors of the war and fears of rising Bolshevism in Eastern Europe made many Americans wary of immigrants and foreign entanglements. The desire to return to the isolationism of the past was expressed in stark terms when the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected American membership in the League of Nations. Without American participation, Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic dream of a world body that would promote and protect international peace was doomed to ineffectiveness.

America soon passed stricter immigration laws targeting Italians, Jews, and other people from Eastern Europe. The Ku Klux Klan, a racist terrorist group born out of the defeated Confederacy, was revived in the 1920s. Alongside its traditional hatred of African Americans, the invigorated Klan had a new emphasis on keeping foreigners, especially Catholics and Jews, out of America.

Laws were also passed to battle what was seen as a growing threat of socialism after the Russian Revolution created the communist Soviet state. During the war, the Justice Department had created the Alien Enemy Bureau to keep track of the half million Germans on American soil. After the war, America underwent what was called the Red Scare of 1919–1920, when federal authorities in the Justice Department’s General Intelligence Division arrested thousands in an effort to round up suspected socialists, anarchists, and radicals. Although the department was criticized for abusing Americans’ civil rights during this period, most Americans were reassured. The intelligence division was later folded into the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation, now known as the FBI.

Even though many wanted to forget the horrors of the Spanish flu—in what medical journalist Gina Kolata later called “collective amnesia”—America had been changed. Part of the response was to enter a new era, what would be called the Jazz Age and Roaring Twenties. The booming stock market on Wall Street was the centerpiece of a new American economy that seemed to know no limits. The country was firing on all cylinders as the Automobile Age began and America sped into the twentieth century.

While the nation wanted normalcy, it also wanted to forget its recent troubles. As people left farms for factories and began moving to growing cities, a popular song of the time asked, “How ’ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm (after they’ve seen Paree)?”

In art and fashion, the world was becoming thoroughly modern. Radio stations blared the new music called jazz. “Moving picture” theaters, some of which had been shuttered during the pandemic, sprouted across the country as Hollywood became America’s entertainment center.

American women, in particular, tossed aside many traditions and conventions. New hairstyles, “flapper” dresses, and “shocking” dances like the Charleston appeared. As wartime had pushed more women into the workforce, many were beginning to look toward careers and professional lives. The large number of nurses enlisted in the flu effort had changed what had once been a volunteer job into a more established profession. And in 1920, American women finally got the right to vote with ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Many of the women who marched and demonstrated for the vote were also pressing for Prohibition—outlawing alcohol. A belief that the nation had become too criminal and violent because of widespread drunkenness had led to ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919.

American medicine was also undergoing a transformation. The Spanish flu pandemic had underscored the importance of serious scientific research. Once far behind the standards of European medical and scientific research, American universities and government agencies gradually modernized and upgraded America’s scientific facilities. “Around the world, authorities made plans for international cooperation on health,” writes John M. Barry, “and the experience led to restructuring public health efforts throughout the United States.” Working without the United States, the League of Nations created its Health Section in 1922, with a focus on coordinating international quarantines to limit the spread of contagion in the war’s aftermath. (It was the forerunner of the current United Nations’ World Health Organization, or WHO.) The public gradually forgot the specter of the Spanish flu, but research into the flu and other diseases continued. It took Congress ten years to finally pass legislation in 1930 that created the National Institute of Health, establishing a new era of federal support for medical and scientific research.