CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAOS AND INDECISION

… the distinction between heroism and villainy begins to blur, and it is not easy to distinguish between errors of omission or of commission.

The Day The Admirals Slept Late,

A. Hoehling.

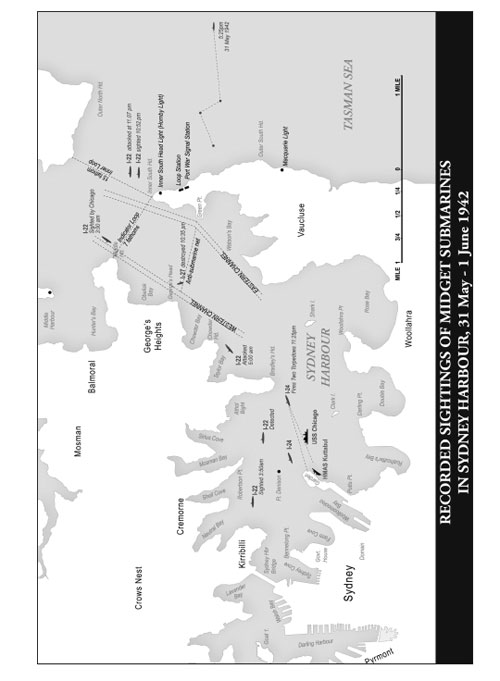

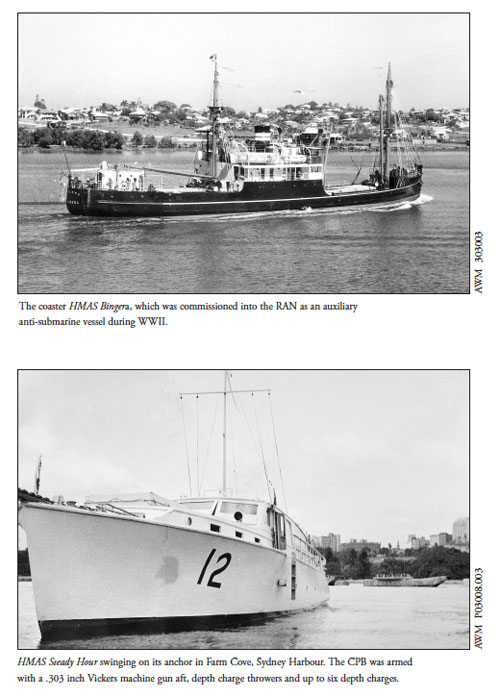

In the confusion that followed the sinking of Kuttabul, searchlights pencilled the harbour, seeking an invisible enemy. The anti-submarine vessel HMAS Bingera slipped her moorings at Man-of-War Anchorage and began to patrol between the anchorage and Bradley’s Head, while Yarroma and Lolita covered the West and East boom gate openings, respectively. NAPs Lauriana, Allura and Yarrawonga were ordered to assist at the boom net area while Yandra continued to criss-cross the harbour entrance between North and South Head. The minesweeper Goonambee, which had already weighed anchor from Watson’s Bay, patrolled along the western channel.

At 1:10 am, forty minutes after Kuttabul had sunk, Muirhead-Gould notified all ships: “Enemy submarine is present in the harbour and Kuttabul has been torpedoed.” Muirhead-Gould’s worst fears had been realised.

Small motor launches scurried around the harbour at high speed in an attempt to keep the submarine submerged while the American ships Chicago, Dobbin, and Perkins, the Australian cruisers Adelaide, Canberra, and Westralia, and corvettes Whyalla and Geelong, and the British converted troop carrier Kanimbla, prepared to go to sea.

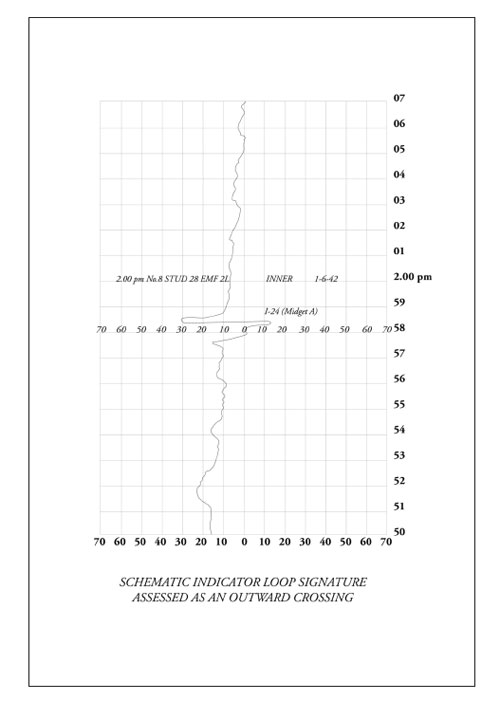

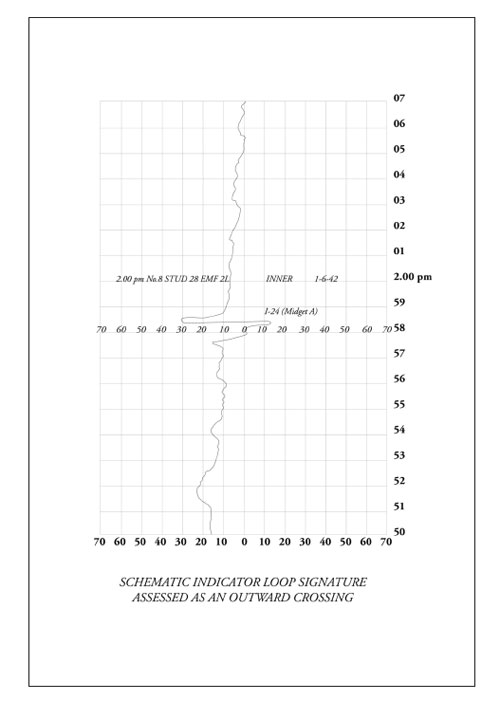

At 1:58 am, another crossing was recorded on the inner indicator loop. It was thought this crossing was a third submarine entering the harbour. However, Lieutenant Matsuo and Petty Officer Tsuzuku, in Midget I-22, were still lurking at the harbour entrance. The next day, Muirhead-Gould and a visiting American electrical expert, Professor L. A. Rumbaugh, analysed the loop signature and came to the conclusion that this was an outward crossing.

The outward crossing was that of Lieutenant Ban and Petty Officer Ashibe making good their escape from the harbour after firing both their torpedoes.

Muirhead-Gould’s draft report [undated] concerning this crossing suggests he was unaware of this signature until much later when he writes: “There was some lack of co-ordination between my operations staff, the Loop Station, and shore defences.”

The inefficiencies of the Loop Station were highlighted as early as January 1942 when Acting-Captain Harvey Newcombe advised Muirhead-Gould he was not satisfied with the watch-keeping scheme at the Loop Station. Many years after the war he recounted the detection equipment had not been properly manned, and some equipment was out of action. In fact, four of the outer loops were operational but not fully tested and, therefore, unmanned.

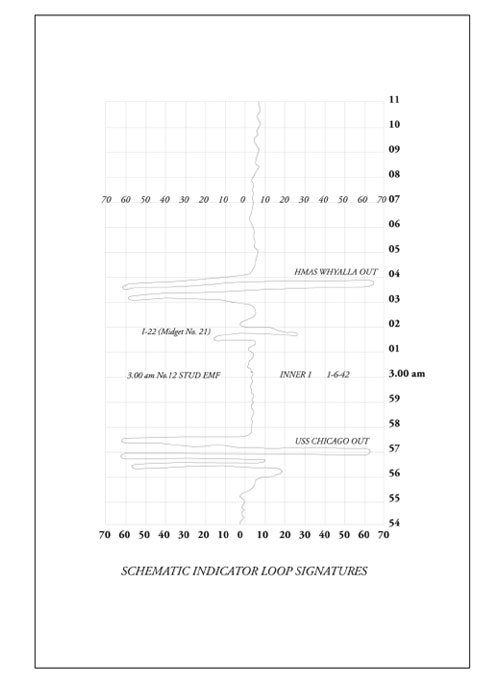

At 2:14 am, Chicago slipped her moorings at Man-of-War Anchorage and proceeded to sea, passing through the West Gate opening, which was now illuminated by searchlights, at 2:56 am. A few minutes later, the heavy cruiser sighted a periscope almost alongside, too close for the heavy cruiser’s guns to bear. At 3:00 am Chicago notified Garden Island: “Submarine entering harbour”. One minute later, a signature was recorded on the inner loop. Lieutenant Matsuo and Petty Officer Tsuzuku, who had waited patiently on the seabed, were now making their entry into the harbour through the West Gate.

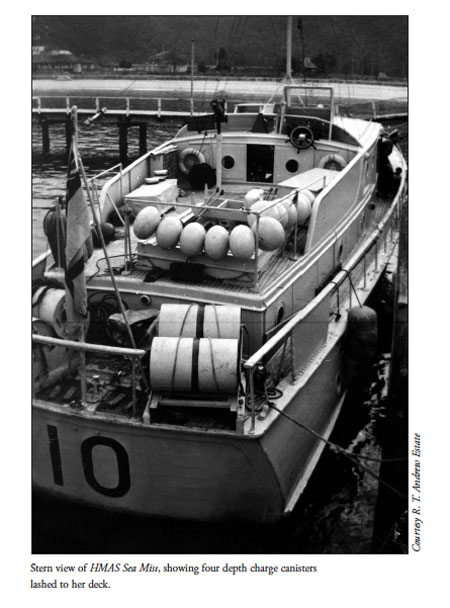

Meanwhile, at Farm Cove, several off-duty patrol boats were still at their moorings, either unaware of the commotion on the harbour, or without adequate crews to proceed on patrol. Most had switched their R/T sets off for the night. Although Muirhead-Gould’s report records the channel patrol boats at Farm Cove were ordered to patrol the vicinity of Bradley’s Head and the boom gate area at 2:30 am, Lieutenant Wilson later recounted to the official naval historian that the CPBs were unable to see visual signals from Garden Island.

Channel Patrol Boats were anchored in Farm Cove on the other side of Macquarie’s Point, and they were unable to see visual signals from Garden Island. Long delays occurred sending messages by launches … Very few CPBs carried depth charges … All concerned in the port did as well as communications, craft, and armaments permitted. They should be applauded … Though records show that the four “stand off ” CPBs in Farm Cove were not ordered to proceed until 2:30 am on 1 June, I am sure they were away and in the vicinity of the Heads before midnight on 31 May.

Channel patrol boats Marlean and Toomaree had slipped their moorings at Farm Cove shortly before midnight to see what all the commotion was about, while Esmerelda, Leilani, Steady Hour and Sea Mist were still at their moorings, unaware of the activity on the harbour. In an interview with the author in 1978, the commanding officer of Sea Mist, Lieutenant R. T. Andrew, said the order didn’t reach Farm Cove until 3:10 am when he was awoken by the sound of a speedboat and a frantic cry, “I think you’d better get underway. There are subs in the harbour.” He immediately relayed the news to Acting-Flotilla Leader, Lieutenant A. G. Townley on Steady Hour, who instructed him to patrol between Bradleys Head and the West Gate. Townley also ordered the depth charges to be set to 50 feet.

Sea Mist was the first to slip her moorings at 3:15 am followed by Steady Hour, which proceeded to the West Gate near Georges Heights. Leilani was unmanned and unable leave her moorings. Esmerelda, with her engines unserviceable, was also unable to proceed.

Andrew recounted he was starved of information and unfamiliar with his new command in a darkened harbour. As he groped his way towards Bradleys Head, he memorised the current recognition signals while manoeuvring between a multitude of ships, hoping that the patrol boat would not be mistaken for the enemy and riddled with bullets.

Arriving at Bradleys Head, Sea Mist began her patrol to the West Gate, keeping to the main channel and running parallel to the darkened shoreline. Andrew instructed his coxswain to remove the sea lashings securing the depth charges.

Hereafter, a period of quiet followed during which the Indian corvette, HMIS Bombay, left the harbour and Bingera moved to Farm Cove to carry out an anti-submarine search in the vicinity of the heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra, which was on “four hours notice” to raise enough steam to proceed to sea.

Suddenly, at 3:50 am, the harbour was again awakened when the British armed merchant cruiser, HMS Kanimbla, which was on 12-hours notice, sighted a periscope in Neutral Bay. Illuminating the periscope with searchlights, the merchant cruiser opened fire. Bingera raced over from Farm Cove to assist but the periscope had already disappeared. Although Bingera criss-crossed the vicinity for the next hour, no further contact was made.

The mood of the harbour was jittery and the slightest indication of a submarine was pounced on. On patrol in the western channel, minesweeper Goonambee flashed Sea Mist to investigate a suspicious object in Taylors Bay. The CPB made a thorough search of the bay but failed to confirm Goonambee’s sighting and resumed her patrol.

There followed another peaceful interlude until 4:40 am when lookouts on Canberra reported an unconfirmed sighting of torpedo tracks from the direction of Bradley’s Head. At the same time, the minesweeper Doomba reported an ASDIC contact off Robertson Point. The minesweeper signalled nearby Bingera for assistance and both vessels launched a determined search of the area. Once again, the submarine eluded them and no further contact was made in that area.

Shortly before 5:00 am, Sea Mist was heading down the western channel from the West Gate when Lieutenant Andrew saw a dark object off Taylors Head, approximately half way between the channel patrol boat and the shoreline. Turning to starboard, he headed towards the object, instructing the boat’s signalman not to illuminate the object. Drawing closer, they both saw a midget submarine on the surface, the conning tower protruding some three feet above water. Continuing in a starboard turn, Sea Mist ran between the submarine and the shoreline until they were both pointing towards the West Gate. Andrew told the author it was a shattering experience to find a submarine on the surface and it caught him very much off guard and far from ready to deal with the situation.

Lieutenant Andrew continued turning in a tight circle and called for the Verey pistol and flares to be brought up from the wheelhouse. He observed that the submarine was starting to dive while the channel patrol boat was still turning on the arc. The patrol boat arrived over the swirling water where the craft had now disappeared. Firing a red flare into the sky, Andrew ordered a depth charge dropped over the stern. At the same time, he pushed the throttle wide open to clear the area in the five seconds before the charge detonated.

The detonation was devastating, followed by a huge wall of water, which the 62-foot Sea Mist rode like a surf boat. A column of water shot skywards and, looking up, Andrew thought the stars would be extinguished. He returned to the vicinity of the depth charge explosion to assess the results of his attack and heard the whirring of propellers churning through the water before he saw the submarine slowly rising upwards out of the sea. As it continued to rise, two contra-revolving propellers became visible within a metal cage. The force of the detonation had forced the craft upwards, and it now laid exposed and inverted, thrashing helplessly on the surface.

Realising the necessity to press home the attack, Lieutenant Andrew turned Sea Mist and once again found himself between the midget submarine and the shoreline. He ordered the coxswain to set a second depth charge to 50 feet and called for another flare. Suddenly, there was a cry from the stern. Andrew’s first impression was that another two submarines were astern of the patrol boat.

I had time to note that a second submarine seemed to be in the process of diving, but the aspect was peculiar. The submarine was not moving forward and the conning tower was boiling with escaping air. It was slipping below the surface and then I realised it was sinking.

Although Andrew insisted later that he saw three submarines in Taylors Bay, he could only have seen one. Nonetheless, with the realisation that there might be more than one submarine in the vicinity, he decided to demolish the inverted craft as quickly as possible. Firing another flare into the sky, he ordered the coxswain to release a second depth charge. Andrew said later that the release point was so close he could easily have stepped off the bridge and on to the hull of the submarine.

As the flare mushroomed downward, bathing the vicinity in red light, Sea Mist desperately tried to clear the area to avoid the detonation. The crew braced themselves and waited for the tremendous upheaval that would follow. When it did, Sea Mist was dealt a crippling blow. At once, her 10 knots were reduced by half and the stoker reported one engine had stopped. With the patrol boat’s speed reduced to five knots, Lieutenant Andrew considered it unlikely he could carry out another attack and safely clear the danger zone in time.

Andrew said after the war that he was concerned when he was ordered to set his depth charges at such a shallow depth. As he explained: “When I encountered the submarine, I only had four to five seconds to clear the area after dropping my charges, and at my maximum speed of 10 knots, it did not give me much of a safety margin.”

After surveying the damage to Sea Mist, Andrew realised his boat was virtually disabled. He flashed Steady Hour for assistance and, although nearby, the CPB did not respond. Sea Mist limped closer to Steady Hour so Andrew could converse by megaphone.

Flushed with success, but disappointed at not being able to press home the attack, he was ordered to return to Farm Cove.

The flares fired from Sea Mist were seen by a number of vessels in the harbour, including Lolita who came racing to the scene along with Yarroma and Goonambee. The coxswain of Lolita described the scene as a “swarm” of small naval vessels, but the CPB was ordered by Steady Hour to “stand-by”.

At this time a North Shore ferry appeared from nowhere and Lolita attempted to head it off before it entered the “danger area”. Only under threat of machine gun fire across the bow did the ferry master finally divert his course. Ferry masters later criticised the patrol boats which, they said, had been running all over the harbour indiscriminately dropping depth charges. In all, there were 17 charges dropped.

From 5:10 am until 8:27 am, Steady Hour and Yarroma searched the vicinity for the midget submarine. At 6:40 am, Steady Hour dropped two charges and at 6:58 am Yarroma picked up an ASDIC contact and dropped one charge. At 7:18 am Yarroma made a second attack, and at 7:30 am Steady Hour reported that her anchor had caught up in the submarine and that light oil and large bubbles were clearly visible. Yarroma carried out a third and final attack at 8:27 am where oil and air bubbles continued to rise.

Rear-Admiral Muirhead-Gould recorded in his preliminary report that although he thought Sea Mist’s claim of three submarines sounded “fantastic” at the time, he considered it was possible.

Members of her crew drew a most convincing sketch of the stern cage of the submarine, which they claim to have seen. At this time, no one was aware that these submarines had tail cages. It’s unfortunate that all efforts to locate this submarine have failed.

Muirhead-Gould recorded that he considered Steady Hour was responsible for sinking this midget submarine. He added that Yarroma and Sea Mist were equally concerned in the submarine’s destruction and therefore, to some extent, Yarroma had made up for her previous indecision.

It seems more likely Matsuo’s craft was crippled by Sea Mist at 5:00 am on 1 June. An examination of the wreckage after the attack revealed it was unable to fire its two torpedoes. The torpedoes were protected by metal caps that were pushed off before firing and an attempt had been made to fire one torpedo; however, the metal cap had jammed against the damaged nose-guard.

It’s plausible Lieutenant Matsuo’s craft was sighted by Kanimbla off Robertson Point at 3:50 am, and again by Doomba who reported an ASDIC contact off Robertson Point at 4:50 am. A conning tower was sighted by Mr Robert Dulhunty from his balcony in Mosman. The sub seemed like it was at the bottom of his garden in Little Sirius Cove. Mr Dulhunty and his father, also Robert, are probably the only civilians to have opened fire on the midget submarine. The 24-year-old accountant at the time fired two shots at the conning tower with his .22 rifle, and his father fired off another two rounds before the conning tower disappeared.

Unable to fire his torpedoes owing to damage sustained to the submarine’s nose guard earlier in the night, Matsuo and Tsuzuku may have been caught while trying to escape the harbour when sighted in Taylors Bay by Sea Mist. When first discovered, Lieutenant Andrew reported the submarine was pointing towards the West Gate. What seems like hurriedly drawn charts ( Appendix D) recovered from the midget submarine after the Sydney raid supports the notion Matsuo had planned his escape from the harbour along the western channel.