CHAPTER TWO

SUNDAY EVENING, SYDNEY HARBOUR

We got into Port Jackson early in the afternoon and had the satisfaction of finding the finest harbour in the world in which 1000 sail of line may ride in perfect security.

Arthur Phillip, 23 January 1788

In the pre-twilight hours of Sunday 31 May 1942, a crisp and wet south-westerly wind moistened Sydney Harbour. Sunset came at 4:53 pm and a full moon was due to rise at 6:11 pm. The ragged coastline from Dee Why to Bondi was majestically silhouetted against the waning light, with Middle and South Heads visible against the foreshore lights of the harbour suburbs. It was the end of another Sunday and Sydney residents were settling into their lounge chairs to listen to the war news on their wireless sets.

Inside the harbour the calm waters were dark and occasionally lit by moonlight, which penetrated the overcast sky. The serenity was disturbed only by fishing boats sprinkled about the harbour, their crews busy setting nets for the night. The Manly ferry plied the harbour as she transported her passengers to Circular Quay and the cinema.

For the past two months Sydney had been crowded with American servicemen, and the Australian way of life had become decidedly lighthearted. At the State Theatre Abbott and Costello in Keep ‘Em Flying was into its second week. (Ironically, the same feature film had been playing in Honolulu the night before Pearl Harbor was attacked.) A reduced admittance fee of one shilling for men and women in uniform had caused a long queue to form along the footpath. The theatre soon sold out and about 300 people were turned away.

A new group of American sailors, recently returned from the Coral Sea, flocked to the David Jones restaurant on Elizabeth Street where a party was held in their honour. Australian girls crowded the entrance to catch the eye of an American GI, or a wandering sailor.

On the harbour, Hornby Light at Inner South Head and Macquarie Light at Outer South Head came on as usual. The floodlights at Garden Island were switched on where work was being done on the construction of a new dry-dock. The obtuseness of defence authorities in allowing these lights to be used before they were eventually extinguished gave the Japanese a floodlit scene.

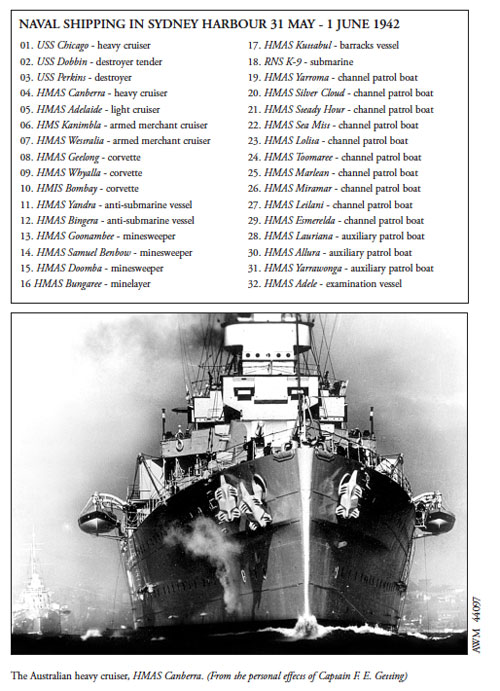

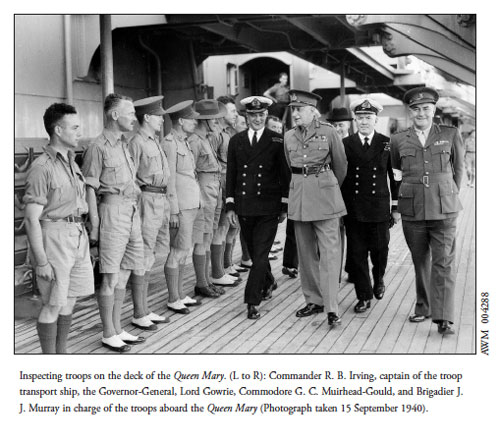

The harbour was filled to capacity with naval and commercial shipping. Wharves and buoys were fully occupied with many more vessels at anchor. There were no large transport vessels in the harbour; the Queen Mary and her sister ship, Queen Elizabeth, had sailed some weeks earlier, their decks crowded with thousands of troops en route to battle areas overseas. The Flagship of the Australian Squadron, the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia, had gone to sea only a few days earlier.

Over preceding days, the Dutch/Australian hospital ship, Oranje, had been discharging wounded troops from the Middle East, among them the distinguished Roden Cutler who had earned the Victoria Cross for heroic action in Syria. At 4.10 pm, Oranje slipped her moorings and proceeded out of the harbour with her decks aglow; but the Third Submarine Company merely watched and allowed her to pass unmolested.

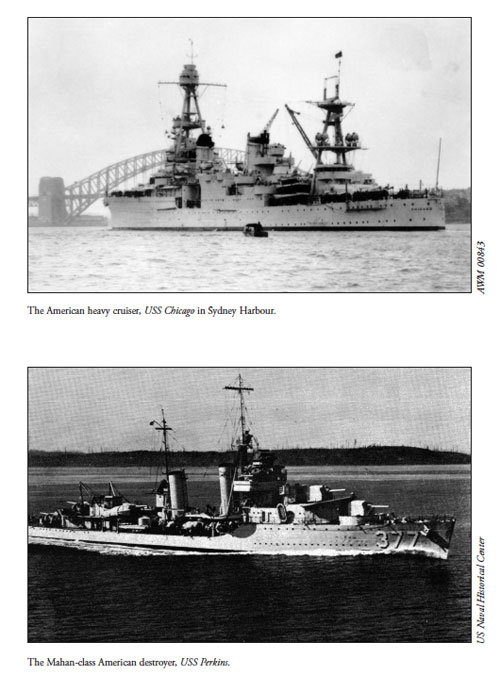

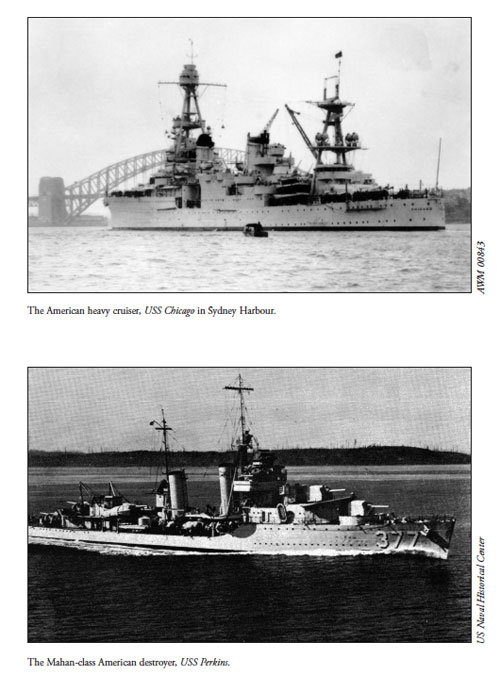

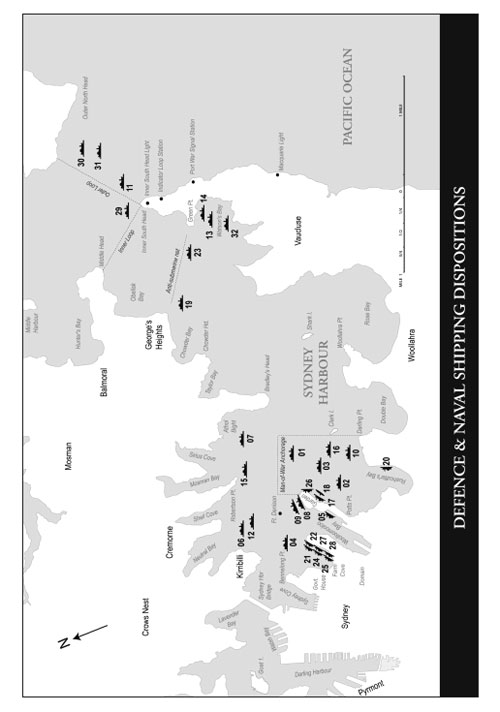

Commercial shipping movements were heavier than usual that evening. Between 5:17 am and 6:55 pm the merchant ships Cobargo, Erinna and Mortlake Bank entered the harbour and made their way down to Walsh Bay to unload their cargoes. In addition to commercial shipping, there were over 40 Allied naval vessels congesting the harbour on that Sunday evening. This unusually large contingent was present because a number of vessels had recently returned from northern waters to repair, re-arm and refuel following the historic Battle of the Coral Sea. The heavy cruiser, USS Chicago, had taken up her mooring at Man-of-War Anchorage after completing a minor refit at Cockatoo Island dockyard where her 1.1-inch machine guns were replaced with automatic, rapid fire “Bofers”. Similarly, her destroyer escort, USS Perkins, had just completed an overhaul after six months of steady steaming at sea, often at high speed. The most valuable targets from the Japanese point of view were the five American, British and Australian cruisers, three of which were carrying aircraft and highly explosive aviation fuel.

As darkness descended on Sunday 31 May, a mood of tranquillity came over the harbour and defence personnel relaxed for the evening. At Farm Cove, seven off-duty channel patrol boats (CPBs) had stood down for the night. The crew of HMAS Leilani had gone ashore for the night, leaving only a quartermaster on board. The leader of the Channel Patrol Boat Flotilla, Lieutenant-Commander E. Breydon, moved his boat, HMAS Silver Cloud, to Rushcutters Bay to be near his residence. The commander of HMAS Steady Hour, Lieutenant A. G. Townley, relinquished command of his patrol boat early in the evening, but decided to remain on board to allow the new skipper, who had family in Sydney, to go ashore for the evening.

Lieutenant R. T. Andrew assumed command of HMAS Sea Mist at midnight and arrived onboard at 4:00 pm. Since he was not rostered for patrol duty until the following morning, he decided to retire early. Also in Farm Cove was HMAS Marlean and HMAS Toomaree, which were manned, fuelled, and on standby to proceed on patrol.

HMAS Yarroma, commanded by Sub-Lieutenant H. C. Eyers, was rostered for duty and slipped her moorings at Farm Cove at 6:00 pm to proceed to the harbour entrance and the West Gate boom net opening, which was still under construction. On arriving there, he decided to drop anchor. HMAS Lolita, commanded by Warrant Officer H. S.

Anderson, slipped her moorings in Farm Cove at the same time to patrol the East Gate channel opening.

At Rushcutters Bay, Naval Auxiliary Patrol Boat (NAP) flotilla leader, L. H. Winkworth, slipped the moorings of HMAS Lauriana, also at 6:00 pm, and proceeded to the harbour entrance. Winkworth contacted flotilla vessels HMAS Yarrawonga and HMAS Allura shortly afterwards, giving them instructions to patrol between North and South Heads with the anti-submarine vessel, HMAS Yandra.

At 6:15 pm Winkworth contacted Yarroma at the West Gate and received information on the local fishing boats, which were permitted to fish in certain restricted areas. Winkworth recorded in his vessel’s running log that it was then dark and Lauriana proceeded on patrol between the heads with all her lights out. The moon was up but a patchy sky clouded it at frequent intervals. There was a steady roll coming through the heads, and no ships were sighted entering the harbour.

At Garden Island, some of the ship’s company of HMAS Kuttabul had gone ashore for the night, while others were rostered for duty or remained behind to catch up on their letter writing. Also allotted a billet on Kuttabul was Leading Seaman Diver W. L. Bullard. The previous afternoon he had secured the 42-foot diving pinnace between Kuttabul and the sea wall, taking the woollen gear, helmets, suits and telephone to the diving shed, but leaving all the heavy gear in the boat including pumps, air hoses, breast lines, boots and weights. He then proceeded ashore to his home in the inner Sydney suburb of Gladesville.

Also at Garden Island, the duty staff officer, Lieutenant Commander C. F. Mills, handed the watch over to his assistant, Lieutenant P. F. Wilson, who maintained his watch from Rear-Admiral Muirhead-Gould’s staff offices on the eastern side of Garden Island. The Operations Room looked out over Man-of-War Anchorage and the harbour. Wilson had a direct telephone link with both Combined Defence Headquarters located in the city, and “Tresco” at nearby Elizabeth Bay, the official residence of the Naval Officer-in-Charge of Sydney Harbour. Muirhead-Gould was fond of entertaining and on this particular evening he had invited Chicago’s commanding officer, Captain H. D. Bode, and other ships’ officers to dine with him at Tresco.

On the other side of the harbour, at Admiralty House, the Governor-General, Lord Gowrie VC, who played an important behind-the-scenes role in Australian politics, had just arrived in Sydney from Canberra. The Governor-General’s official Sydney residence, situated on Kirribilli Point, had a dress circle view of the harbour.

Shortly before sunset, the Third Submarine Company took up position 7 to 10 miles east of the harbour and prepared to launch three midget submarines. Those who turned in early in preparation for the coming week, were destined to be savagely awakened by a pandemonium of gunfire and explosions as the Australian forces reacted to a surprise raid by Japanese midget submarines.