11

New Figures of Woman

In 1834, Balzac wrote a novel entitled A Woman of Thirty. In 1832, curiously, Freud ends his lecture on femininity with some considerations on the thirty-year-old woman.

Balzac and Freud were writing a century apart, in two different languages, were living in two countries, although they were both Europeans, and operated within two different discourses.

The title Lacan gives to his seminar, L’envers de la psychanalyse, is an allusion to another title by Balzac, The Reverse of Contemporary Life (L’envers de la vie contemporaine).1 Balzac, obviously, writes from the point of view of the reverse (envers). As for Freud, in 1932, when he gives his final assessment of his analytic experience of women, his message is radically opposed to Balzac’s.

The implicit message of Balzac’s novel, seen from today, is one of progress, which anticipates something of the evolution of women’s conditions. Balzac writes to say that at the age of thirty, his heroine, despite her misfortunes, has her life in front of her. In this case, the future means love, and also the possibility of determining her own life. As the jacket of my copy of the novel says, “She is not forbidden from becoming a human being.”

This has nothing in common with Freud’s final sentence, which although well-known, is still very striking:

A man of about thirty strikes us as a youthful, somewhat unformed individual, whom we expect to make powerful use of the possibilities for development opened up to him by analysis. A woman of the same age, however, often frightens us by her psychical rigidity and unchangeability. Her libido has taken up final positions and seems incapable of exchanging them for others. There are no paths open to further development; it is as though the whole process had already run its course and remains thenceforward insusceptible to influence—as though, indeed, the difficult development to femininity had exhausted the possibilities of the person concerned.2

This paragraph comes after some considerations on the drive, in which Freud emphasizes that women’s drives are less plastic than men’s. He gives two well-known examples as proof: the lesser aptitude of women’s libido to be displaced onto compromise formations—especially the sense of justice and fairness—and to be sublimated into the creations of civilization. Freud’s thesis is categorical: the drives have been fixed immovably. Is this a simple prejudice on the part of the very traditional Freud? Perhaps. This is the mainstream opinion. I do not doubt, furthermore, that every enunciation bears the mark of the subject’s sexual inscription; nevertheless, I do not think that we can get rid of Freud’s thesis by positing simplistically that he was more prejudiced than other people. We know at least that his prejudices did not prevent him from inventing psychoanalysis, and this is enough to indicate, as Lacan said, that he had a “sense of orientation.”

If I tried now to draw a portrait of a thirty-year-old woman of today, in 1995, I believe that it would be different once again: she would be neither Balzac’s nor Freud’s woman. In the discourse of the reverse, it is indisputable that many things have changed since the 1930s. Women are no longer as they were, and if we were to rewrite Balzac’s novel, it would have to be very different. These mutations of reality are not enough, however, for us to discard Freud’s thesis. It seems to me that today, the question is the following: How and to what extent have these changes at the level of the discourse of the reverse, by obviously modifying women’s desire, also modified the economy of the drives, and especially of the part of jouissance that does not proceed by phallic mediation, the part that is “not whole”?

In his final paragraph, Freud, conscious of the malaise that he is going to produce, tries, in order to make his judgment more nuanced, to introduce a distinction that is not unrelated to the one that I mentioned earlier. He says, “[D]o not forget that I have only been describing women in so far as their nature is determined by their sexual function. It is true that that influence extends very far; but we do not overlook the fact that an individual woman may be a human being in other respects as well” (p. 119). The German text can be checked: the expression “human being,” used in the French and English and suppressed in the Spanish translation, is correct. Thus Freud establishes, concerning woman, a cut between what can be called her being for sex—as one says, “being for death”—and her belonging to humankind: the universal of the speakingbeing.

CHANGES INSIDE-OUT

The institution of the family, the semblances, and the discourse on sexual jouissance are no longer what they were several decades ago.

Lacan, at the end of his text on feminine sexuality, asks himself whether it is not women who have maintained the status of marriage in our culture. Today, this remark from 1958 seems largely irrelevant. Numerous indications—at the level of statistics, the evolution of legislation, and so on—indicate that the status of marriage has changed radically in the last two or three decades. The disturbance of this status, which reaches an extreme in the dissociation between marriage and sexual life as well as maternity, has not yet become general, but can be seen quite clearly, at least in the United States. To bring up a child alone, or in a homosexual couple, or in a partnership between a woman and a homosexual, and so forth, are configurations that are not only possible, but ever more frequent and legal. They are especially symptomatic of changes in discourse that have taken the scandalousness out of the category of unmarried mother. Couples who do not want to be married can obtain the legal benefits of marriage; homosexuals of both sexes can be married, and as a correlate, the status of the family is changing with surprising speed. People are obviously asking questions about the long-term subjective repercussions of these changes on children. The structure of the traditional family is not the necessary condition for the paternal metaphor, but when the effect of the fragmentation of social bonds touches the elementary cell to the point of producing single-parent families, and the individual becomes the last residue of this fragmentation, we must necessarily anticipate some consequences, as impossible as they may be to foresee.

For some time already, we have been talking, almost as a banality, about the fall of semblances, or at least their pluralization. It is obvious that the ideal of what a couple should be has been included in this general fall. Let us take, as our reference point, because of its dates, Léon Blum’s book On Marriage, which was first published in 1907 and then reprinted in 1937. At the time, it was an ideological bombshell, a provocation: in the name of erotic satisfaction, he argued in favor of sexual freedom, fought traditional values linked to marriage, especially abstinence outside marriage, recommended, in order to forestall future disappointment, multiple sexual experiences before one makes any definitive choice. This struggle for sexual freedom has become out-of-date in the context of today’s mores and we can sometimes find it amusing. When condoms are sold at the doors of high schools, when fidelity, which was once a value, is reduced more and more to a subjective requirement or to a personal disposition, when houses of prostitution are launched by having an “open house” for potential clients, when prostitutes testify on television, then exalting free choice no longer has any meaning. The “images and symbols” of women have changed drastically. The same semblances are no longer drawn on the masks: the place of the “girl phallus” remains, but Zazie and other Lolitas have been substituted for the virginal innocence that Valmont enjoyed despoiling in Les liaisons dangereuses, and the femme fatale of the great age of Hollywood has herself been replaced by supermodels with empty gazes. As for man, the theme of the possible disappearance of manliness has been circulating for some time now. In short, therefore, and without a more ample survey, we can see that the semblances that ordered the relations between the sexes are no longer what they were.

As a correlate, the place given to jouissance in discourse about love has been modified greatly in recent decades. Whatever the causes may be, we are the contemporaries of what I would call a legitimation of sexual jouissance. This was not the case of the age in which Freud analyzed and wrote. Sexual satisfaction appears as a requirement so justified, a dimension so natural, an end in itself so independent of the aims of procreation and the pacts of love that not only has it become the object of a discourse that is public—and no longer intimate—but it has also become the object of attention and care for an entire series of therapists and sexologists.

Psychoanalysis may not be completely innocent in this evolution of mores, but something like a de facto right to sexual jouissance is added today to the list of the modern subject’s rights (see all the polemics concerning female circumcision). Furthermore, sexual jouissance is subject today to the discourse of distributive justice. Everyone can now lay claim to his/her own orgasm, and sometimes even in court! All we have to do is to read the press in order to see how far this has gone.

What are the effects of these changes for women? What are their effects at the level of the economy of the drives?

THE “PHALLIC RECUPERATION”

As I have already said, all the new objects of the “recuperation of the sexual metaphor”3 are offered to all people, without distinction of sex. In the field of reality that is founded on desexualization, when it comes to conquering knowledge, power, and more generally, all the products of surplus jouissance engendered by civilization, the arenas of competition are now open to women. It seems that the recognized and accepted substitutes for the lack of the phallus have themselves been multiplied: this is why I have spoken of a general unisex.

We can also question what happens at the level of the sexual relation. Lacan challenged Freud’s belief that the child wanted by a woman, and who is the consequence of a man’s love, is the only phallic substitute that is in harmony with feminine being. Today, with the discourse of the legitimation of the sex, it is clear that this substitute is not the only one. Depending on the case, the organ itself, discreetly fetishized, can be such a substitute, as can a more recent development, the series of lovers who dispense the phallic agalma, not to speak of women who become lesbians and those who disdain motherhood.

RETURN TO FREUD’S WOMAN

In the light of these changes, it is important to explain, or rather to interpret, Freud’s position: Why did he think that the only positive evolution of the libido in a woman was her transformation into a mother? Lacan, we repeat, diverges on this point, but Freud’s reduction of woman to mother does not seem to me to have been explained completely.

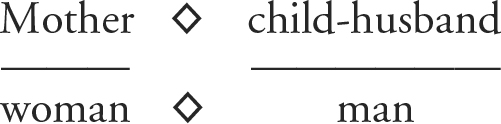

Freud affirms this thesis categorically throughout his elaborations, and it appears very clearly in his text on femininity. Not only does it destine woman to be the mother of her own child, but it also seeks to make her the mother of her husband. After some considerations on the bond with the child, he notes that “a marriage is not made secure until the wife has succeeded in making her husband her child as well and in acting as a mother to him” (p. 118). The context leaves no doubt about the fact that the child, especially the son, and the child-husband, have the function of satisfying, by proxy, the aspiration to have the phallus. In considering the husband as a reduplication of the child, Freud intensifies his reduction of femininity to the mother’s phallicism. Not only does he say that a woman can have the phallus only through the bond with the child, but he effaces the phallicism of being, which is in play in love, to the profit of a single phallicism: that of having the phallus. This tendency is all the more noticeable since two pages earlier, Freud emphasized what women require from love. As a couple, the mother-woman and her husband, the child-man, make up for the more problematic couple of a man and a woman. This is a metaphor and the substitution can be written as

From the structural point of view, it is obvious to us that the relative failure of Freud’s efforts to find a satisfying conception of the avatars of the libido in women and his constant tendency to make other bonds the metaphors of the sexual bond carry an implicit enunciation, for which Lacan was finally able to give us the statement (énoncé): “there is no sexual relation.” Despite all these considerations, however, the question of Freud’s prejudices has not yet been settled.

It is difficult to say how far Freud considered his conclusions to be absolute, but I would like to emphasize that he introduces the solution of the child-husband as the condition for a marriage’s stability. This fact relativizes his solution, for it connects the supposed norms of a woman’s evolution—making herself into a mother—with the only socially acceptable outcome that Victorian society offered women. Perhaps my remark should itself be made with greater nuance, since it is based on an isolated indication by Freud; just afterwards, he adds some considerations on the erotic value of the mother-woman that go in a completely different direction and that are surprising since they come from the man who diagnosed the debasements of love life so well. This indication testifies, however, to the link between the clinical facts that Freud isolated and the state of discourse in his time, and thus leads us not to attribute everything to his own prejudices.

The lack of the phallus, which is Freud’s sole reference, gives us only half of the phenomenon. The other half is the objects that arise as its substitutes. They function as social bonds and program certain arrangements between the sexes, arrangements that are now dated. They enable us to grasp why Freud’s “impression”—this is his term—of the inertia of libidinal positions in his thirty-year-old woman would not necessarily be shared today, even from the analytic viewpoint. The historical definition of the kinds of surplus jouissance offered to women, or more precisely, the reduced series of objects compatible with the semblances of woman, accounts for a part of the libidinal blockage that Freud perceived. It presents not only a woman who is completely in the phallic problematic, but who is also the captive of social conditions in which there is no safe point outside marriage; such a state condemns her to achieve her phallicism, with a few exceptions, only as a mother. Thus it is not so much a matter of questioning the phenomena that Freud perceived as of seeing what they owe, despite the universal of castration, to the bids of the discourse of his time.

NEW FANTASIES

Today, now that the whole field of phallic acquisitions is being opened to women, we need to ask where, outside the sexual relation (relation) properly speaking, the manifestations of the relation to the signifier of the barred Other and of other jouissance are to be found. We no longer have any mystics and we can wonder whether it is possible to identify the substitutes for yesterday’s mystics.

I believe that the absolute Other, or more exactly, woman as absolute Other, is everywhere and haunts the figures of the same. Contemporary civilization no longer deals with the Other by segregation—at least in the West. Internal segregation was a simple, and perhaps effective, way of dealing with the Other. It plugged up problems by allotting spaces: to each his/her own perimeter, and as a correlate, his/her own tasks and attributes. To a woman the house, to a man the world; to a woman the child, to a man the career. The first could sacrifice herself through love and the second could exercise power, and so on. Today the situation is more mixed, and this, as Lacan said in Television,4 produces new fantasies.

In fact, the rise in the past century of the theme of women seems to be a correlate of the extension of the discourse of human rights and of the ideals of distributive justice. The more the ideology—I think that this term is adequate here—of distributive justice triumphs, with all that it implies of a common measure, the more the Other and its opaque jouissance, a jouissance that is outside the phallic law, takes on existence. We can certainly speak of the modern subject, the Cartesian subject, conditioned by the cogito, but concerning contemporary woman, to know whether she is modern is another problem: she is doubtless so as subject, like anyone, but could it be that she is not, inasmuch as she is Other?

The absolute Other of a jouissance that is not whole, not countable, can hardly be thought of as modern, even if it is foreclosed from a discourse that calls itself such. There may be something well-founded in the rather antiprogressive expression, the “eternal feminine.” On this point, it is not impossible for psychoanalysis to make a contribution. By following Lacan’s indication in Television, which establishes a link between the “racism” of jouissances and religion, in order to predict their revival, we can situate a theme that Encore develops more broadly, that of the two faces of God: the face of God-the-Father, but also the face of an Other god, who is completely other and absolute, and whom woman makes present. This is a very earthly god, but one that is capable nevertheless of arousing “fear and trembling.”

In fact, we can note a certain “uneasiness”—this may be a euphemism—one that is discreet but obvious, toward modern women. It is an ambiguous disquiet, composed of phallic rivalry, but also and especially of frightened fascination, and perhaps even of envy for her Otherness, which unisex does not succeed in reducing. I would argue that this “envy” develops as the shadow of cynical discourse: the idea that women have a jouissance that does not fall within the discontinuity and short duration of phallic jouissance and does not call for a complementary object of lack. Women have an access to something oceanic, to borrow the term that Freud uses for religious aspirations. In lending our ears to this, we sometimes perceive a fascination with the jouissance attributed to women, a fascination that goes in exactly the direction indicated by Lacan: toward God, the god of jouissance, who takes up existence beside woman.

With this thread, we are very far from the classic theme of feminine penis envy. The latter can only arise from a lack, from a sense of frustration concerning something that an other is supposed to have at his disposal. Envy is the sister of the malady of comparison. It is intrinsically linked with the register of phallic jouissance, for the latter is an incarnate objection to any access to beatitude, about which it can, however, dream. Freud was right: envy is very much linked to the phallus. In other words, the absolute Other, as such, never envies.

What is amusing is that women who identify most with the phallus sometimes carry, as a pretense, the agalma of the ineffable other jouissance, and play at bringing about (jouant à faire) the Other, without actually being her. This is my explanation of the surprise provoked by that incredible diva, the divine Marlene Dietrich, when she confessed that she had always been frigid.

NEW SYMPTOMS

What about the new symptoms of contemporary women? I am not going to consider the most recent forms of the internal conflicts that women experience in their relation to the phallus, which have been diagnosed for a long time. Conflicts, tensions between the two types of phallicism—being and having the phallus—far from being reduced only to the opposition between being a woman and being a mother, also take on a new form today, one that has become banal: a tension between professional success and what is called the “emotional life”—let’s say between work and love.

Debasement

I would like first to introduce the theme of the debasement of love life, which Freud diagnosed in men, but which does not spare women. In terms of the splitting between the love object and the object of desire, the evolution of contemporary mores has made new phenomena appear. Lacan, years after Freud, had already spoken in a more nuanced way. His 1958 text, “The Signification of the Phallus,” seems first to adopt Freud’s thesis, which he reformulates by noting that in women, unlike men, love and desire are not separate, but converge on the same object. On the following page, however, he introduces an important nuance: the division between the objects of love and desire is no less present in women, except that the first is hidden by the second.5

Well, what must not be hidden today is that, once liberated from the sole choice of marriage, many women love on one side and desire or get off on the other. They had to escape from the yoke of an exclusive and definitive bond before we could see that their various partners are situated on one side or the other: on the side of the organ that satisfies sexual jouissance or on that of love. The convergence of the two on the same object is only one configuration among others. Here I see an obvious change in the clinic.

Inhibition

There is also another: the new feminine inhibitions. There is only inhibition when a choice is possible, or when there is an imperative. When women were not asked about their desire and were constrained to act in certain ways, they could hardly procrastinate in deciding or acting. Their emancipation multiplies what is possible for them; they can live in any way they like, can choose whether or not to have a child, whether and when to marry, and whether or not to work. This liberation shows that the drama of inhibition is not a masculine specialty. This is all the more true since, in discourse, everything that is not forbidden becomes obligatory. Consequently, we see women shrink before the act in the same way that an obsessional man would; they exhibit the same hesitations when confronted with fundamental decisions and definitive commitments, especially in the domain of love. In the clinic of contemporary life, we frequently encounter women who want a man and a child, but who must defer having the latter until they have met someone better; such situations are often the origin of a demand for analysis. The extension of unisex to the whole of social conduct goes along with the homogenization of a large part of symptomatology.

Women in Charge of Fatherhood

There is a typically feminine configuration that seems to me both frequent and quite contemporary. It can be seen not among thirty-year-old women, but rather among those who are approaching their forties, single, who usually work, who can choose freely whom to be intimate with, and who are beginning to notice that time is passing and that if they want to have a child, they are going to have to hurry. They are going to have to encounter a man who is worthy of being a father, at least if they have not chosen to be single mothers. Since contraception and the legality of abortion have disjoined reproduction from the sexual act more radically than ever, women are obliged not only to decide to have a child but often to take upon themselves the choice of a father; now only age or sterility remains to make the situation impossible. The conjunctures of the desire for a child have changed and have engendered new subjective dramas and new symptoms. They also, however, give women a new power, which, I would argue, could have massive consequences.

We could say that these women put themselves in charge of the father. Diogenes, in his ironic position, claimed to be looking for a man. Today, many women are looking for a father for the child who is to come. Now there are new choices, new torments, new complaints! Their configurations are multiple: “I am looking for a father, but I cannot bear to live with a man”; “I am looking for a father, but the men I meet don’t want children”; “I am looking for a father, but I haven’t found anyone.” Let us also not forget the statement, “I immediately thought that he would be a good father!” The next step is to give the father a lesson about what a father should be, and this sometimes takes the new form of self-reproach concerning the man who has been chosen; she cannot forgive herself for having given such a father to her children.

I obviously do not want to call into question the freedoms that have been conditioned by the disjunction between procreation and love; it is also important not to misunderstand the small bit of freedom that the unconscious really leaves the subject in terms of what is to be chosen. We can, however, notice that these new freedoms place women in a new position, one that allows them, more than ever before, to make themselves the ones who judge and measure the father. Thus, we have seen the development of a discourse of maternal responsibility, one that has reached the point of triumphing over that of the father. This new discourse conveys something like an inverted paternal metaphor, or at least raises to a second power the paternal failure that is specific to our civilization, for it places the mother-woman in the position of a subject who is supposed to know about being a father. We perceive, indeed, that the statement “I am looking for a father,” like Diogenes’s “I am looking for a man,” means “there aren’t any”: “There isn’t anyone who meets my requirements.”

In conclusion, we are not deploring the evolution of our civilization. A psychoanalyst has nothing to criticize: s/he can only report the facts within the perspective of the discourse that determines him/her. Perhaps, for the moment, we do not yet know what are going to be the consequences of the mutations of contemporary woman’s status.

1. Envers can be translated variously as “reverse,” “back,” “underside,” and “wrong side.” Balzac’s novel L’envers de l’histoire contemporaine has sometimes been rendered as The Seamy Side of History. The expression à l’envers, which appears later in the chapter, means “inside out,” “upside down,” or “back to front.” (Translator’s note.)

2. Sigmund Freud, “Femininity,” New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis, trans. James Strachey. SE XXII, London: Hogarth Press, 1964, p. 119.

3. “Guiding Remarks for a Congress on Feminine Sexuality,” p. 91. Translation altered.

4. Television, p. 32.

5. Lacan, “The Signification of the Phallus,” pp. 278–280.