Partridge Chantecler bantam.

Farmers who have had no experience with the different varieties of purebred fowls are very apt to choose a breed because they “like the looks” of the fowls, or because somebody says that particular breed “is the best,” but it frequently happens that their poultry fails to pay, because the breed selected is not the one best adapted to the special purpose for which they keep fowls, and disappointment results.

— Waldo F. Brown, The People’s Farm & Stock Cyclopedia, 1884

Partridge Chantecler bantam.

Humans have depended on domesticated and captive-bred wild birds for thousands of years. These fowl have both fed us and provided us with feathers for uses ranging from strictly ornamental to highly practical (such as goose down insulation). They have played a spiritual role for many cultures and attracted us with their beauty and interesting character.

Our need (both utilitarian and aesthetic) for fowl has resulted in an amazing variety of barnyard birds. There are over a dozen species, hundreds of breeds, and thousands of varieties kept in barnyards and backyards around the country and around the world.

Let this book serve as your guide to the marvelous selection of birds that are kept by farmers and fanciers in North America. This first chapter provides some general background information on the birds of the barn. Next comes a chapter dedicated to chickens (by far the largest group of domesticated birds), followed by chapters on turkeys, waterfowl, and finally some of the other birds that farmers and fanciers raise (such as the upland game birds).

To make it easier to cross-reference breed information, we have highlighted in bold breed names that are discussed in the book and included hyperlinks to the place in the book to which their write-up appears.

Welcome to the fascinating world of fowl. Enjoy your exploration of our feathered friends.

A Silver Sebright bantam is just one of the breeds of poultry raised for show and pleasure.

Trying to understand the natural history of domesticated birds is like doing a giant jigsaw puzzle: as each piece, or clue, falls into place, you begin to get a feel for the picture, yet as other pieces are added the picture can change before your eyes to something you hadn’t quite expected. Biologists, archaeologists, historians, and bird fanciers continue to search for evidence that will help finish the picture, but in the meantime, I’ve gathered some of the prevailing thoughts on where, and how, our domestic birds got their start.

Scientists are fairly certain that there is some connection between our modern birds and dinosaurs. If you see a chicken attacking a hapless mouse that has had the misfortune of finding itself in the coop, the resemblance to a killer dinosaur is very clear, and you’re darn glad that bird isn’t 40 feet (12 m) tall and standing above you.

In fact, most scientists think that birds evolved from the same line of dinosaurs that spawned the bad-guy dinosaur of the movie Jurassic Park, the Velociraptor. Some, however, speculate that birds are more like cousins of dinosaurs, having evolved concurrently from a common ancestor that gave way to dinosaurs, birds, and reptiles about 275 million years ago. Either way, modern birds and reptiles share a surprising number of traits that support the idea of an evolutionary connection, such as scales (which birds have on their legs) and the external incubation of eggs.

The earliest birds that are recognized as such, Archaeopteryx lithographica, were discovered in limestone deposits in Europe and appeared during the Upper Jurassic period (about 150 million years ago). The trip from Archaeopteryx lithographica to our modern birds (subclass Neornithes) included several now-extinct intermediary species and took millions of years. Somewhere around the end of the Cretaceous period, about 65 to 70 million years ago, the relatives of today’s waterfowl showed up, making them among the earliest modern birds that scientists have documented. Then, by 35 million years ago, the ancestors of the majority of modern birds had made the scene.

Guinea fowl, such as this helmeted guinea, are unusual-looking birds that are known for eating insects, snakes, and small rodents.

There are about nine thousand known birds within the subclass Neornithes; these are separated into two major subdivisions: the Eoaves, a rather small group that includes ostriches, rheas, emus, and kiwis; and the Neoaves, which includes all other living birds, from albatrosses and avocets to woodpeckers and wrens (and, of course, chickens, turkeys, and other domesticated birds). Within the Neoaves there are many major subdivisions, but for our purposes the superorders Gallomorphae and Anserimorphae are the two important groups.

The gallinaceous birds, which are members of Gallomorphae, are terrestrial, chickenlike birds with relatively blunt wings that aren’t capable of flying very far. They have strong legs and feet for digging, fighting, and running. There are over 250 species in this group, including many barnyard birds, such as chickens, jungle fowl, turkeys, pheasants, quail, grouse, and guineas.

The Anserimorphae are waterfowl, and there are over 150 species in the group. They are strong swimmers with short, stout legs and webbed feet. They also fly very well, though many of the domestic ducks and geese have been bred to have a large breast, which reduces their flying capabilities. They have a feathered oil gland and down feathers to help maintain their temperature whether in water, on land, or in the air. They also have a thick layer of fat that acts as insulation and provides buoyancy.

One unusual characteristic of waterfowl is the way they molt (shed their plumage). Most birds undergo a gradual molt during which the feathers are shed and replaced slowly, so the birds can still fly during this time. Waterfowl, however, molt all of their flight feathers (wing and tail feathers) simultaneously, with the result that they become flightless for several weeks. You may notice that during the molt period male ducks (wild or domestic) lose their typically vibrant breeding colors and assume a drab appearance like that of the females and juvenile birds.

Turkeys, like this handsome Narragansett tom, are one of the few domesticated species that are native to the Americas.

The Araucana chicken breed provides a great example of the way thoughts are challenged in the scientific world and of how our understanding of history can change over time.

This bantam Araucana rooster’s DNA could hold the key to a mystery: did the Chinese arrive in the New World before Columbus?

There is a great deal of debate about the Araucana and its progenitors, the Collonca and Quetero birds, domestic races that were kept by tribal groups in different areas of Chile. The debate centers on whether these birds predated the arrival of Columbus in the New World, and if so, where they came from. Here is the short version of the story, which, as one Italian scientist wrote, has had lots of ink spilled on it, with more yet to come.

We have all been taught that Columbus discovered America. Until recently the accepted wisdom was that livestock — ranging from chickens to pigs, goats, sheep, cows, and horses — were introduced to the New World by Columbus and the Europeans that followed him. Now, however, there is a divide in the academic community between those who agree with this view and another group that believes the Chinese arrived in South America before Columbus and introduced chickens to the New World.

“There have been repeated rumors about pre-Columbian chickens, generally focused on the Araucana, but this has never been supported by scientific evidence and is considered highly improbable, as is all evidence for any trans-Pacific human migration into South America after the early Holocene [about eleven thousand years ago],” according to Dr. Elizabeth Reitz, an anthropologist at the University of Georgia who manages the zooarchaeology lab. “Both concepts are unsupported in the professional archaeological literature at this time. Chickens are not the only European introduction that spread in advance of Europeans themselves. European-introduced diseases surely spread far in advance of Europeans, as did a number of plant species (for example, watermelon and peaches).”

But the opposite view has its own strong — and well-respected — supporters. Dr. Carl Johannessen, professor emeritus in the geography department at the University of Oregon, is a strong proponent of the view that there were transoceanic contacts between the Chinese and Amerindians before Columbus came to the New World. “Chickens are just one of about 125 species of plants and animals that appear to have moved between Asia and South America before Columbus came,” he says.

Dr. Antonio Alcalde, an agronomist and lecturer on plant and animal domestication at Catholic University in Chile, also supports the pre-Columbian introduction of chickens. “My educated guess is that these chickens were here before the Europeans arrived,” he says.

Both Johannessen and Alcalde point to some strong evidence that the Araucana’s forebears were pre-Columbian chickens, including these five basic points:

Which camp is right in this debate? Only time will tell, but scientists are now using DNA analysis to help solve the puzzle of the Araucana.

The Araucana is known for several unusual traits, such as the lack of tail and ear tufts seen on this bantam hen.

A species is a group of organisms that are genetically similar and have evolved from the same genetic line. Organisms within the same species readily interbreed, exchanging genes to produce viable offspring that are also capable of interbreeding. Sometimes different-yet-similar species are capable of breeding (for example, horses and donkeys), but generally these cross-species pairings result in offspring that are not viable or that are not readily capable of interbreeding (as is the case with the mule, which is sterile).

A breed is a group within a species that shares definable and identifiable characteristics (visual, performance, geographical, and/or cultural) which allow it to be distinguished from other groups within the same species. So, although chickens are of the same species, an Ameraucana is easily distinguished from a Yokohama, and a Dutch Bantam is readily distinguished from a Jersey Giant.

Within breeds there are additional subdivisions for variety and type. Varieties are often defined on the basis of the color of their plumage, the shape of their comb, or the presence of a beard and muffs. Types are defined based on differences in use, such as production or utility types versus exhibition types.

Some chicken and duck breeds have corresponding miniature versions (one-fifth to one-quarter the size of the large bird). There are also some breeds that exist only in a small form. These diminutive forms are referred to as bantams.

Breeds come in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. The Jersey Giant hen (top photo) represents one of the largest breeds and one of the most common colors — Black. Blue Wheaten, as seen in the Ameraucana cock (lower photo), is a somewhat uncommon color.

Breeds have been developed over many millennia. In North America the designation of poultry and fowl into breeds is basically determined, or “recognized,” by one of two groups: the American Poultry Association (APA) and the American Bantam Association (ABA). Both organizations publish a “standard” (the APA Standard of Perfection and the ABA Bantam Standard) that describes each breed in great detail. These standards are used by breeders in selecting breeding stock and by judges at poultry shows in evaluating birds.

Within one breed there is often a large, or standard-sized variety, and a small, or bantam, variety. A standard New Hampshire rooster and a bantam New Hampshire hen are shown for comparison.

The terms purebred and registered do not mean the same thing for poultry as they do for large livestock animals. Rather, poultry that meet the breed and variety descriptions found in the APA Standard of Perfection or the ABA Bantam Standard are said to be “standard bred.”

Founded in Buffalo, New York, in 1873, the APA is the oldest livestock organization in the United States. The ABA formed in 1914 with the goal of setting standards for, and promoting, the bantam breeds. There is some crossover between the two organizations: the APA recognizes many, but not all, of the bantams that the ABA recognizes, and vice versa. In other words, some bantam breeds and varieties are recognized by both groups, while other breeds and varieties are recognized only by one.

When breeds are first introduced to this country, the interested breeders arrange with the APA and/or the ABA to host a qualifying meet. If the birds at the meet show sufficient standardization of characteristics, they may be accepted for inclusion in a future standard. Anyone interested in raising or showing standard-bred poultry (chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese) should invest in a copy of the appropriate standard.

Unfortunately, breeds come and go. New ones are developed; older ones languish when few breeders are interested in them anymore; some breeds become extinct. The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) and the Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities (SPPA) are two of the leading organizations that work on protecting breeds from extinction.

Ducks and other kinds of waterfowl also come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. This Khaki Campbell drake is known for its unique tannish coloring, which reminded Adele Campbell, the English developer of the breed, of Britain’s military uniforms.

The Ark of Taste is a program designed to preserve and celebrate endangered tastes. It does this by promoting economic, social, and cultural heritage foods ranging from animals raised for meat to fruits and vegetables, cheeses, cereals, pastas, and confectionaries. The following breeds were accepted by Slow Food USA (see Resources, p. 261) into the Ark of Taste as of September 2006.

Chickens: Delaware, Dominique, Black Jersey Giant, White Jersey Giant, New Hampshire, “Old Type” Rhode Island Red, Plymouth Rock, Wyandotte

Geese: American Buff, Pilgrim

Turkeys: Bourbon Red, American Bronze (Standard), Buff, Midget White, Narragansett

Since the earliest days of agriculture, countless individuals have dedicated themselves to the care and breeding of poultry. These birds have filled a wide array of human needs for food, fiber, creative and spiritual expression, sport, and companionship. Both human and natural selection have worked together in the evolution of breeds, so that each breed reflects a particular set of characteristics valued in the interplay among the people who depend on them, the birds, and environment.

The Sicilian Buttercup, named for its unusual comb, is a beautiful but critically endangered breed of chicken.

Breed diversity today is a legacy from our ancestors and reflects the ways that they lived.People who lived in cold climates had breeds adapted to the cold; in hot climates, breeds were adapted to the heat and to the greater number of parasites that plague steamy regions. In areas where grass was plentiful, breeds were adapted to good forage, but in areas of poor forage, the breeds were adapted to survive on lower feed quality. Taken together, the breeds within a species represent the species’ adaptability and utility, providing the genetic diversity the species needs to survive and prosper.

The importance of genetic diversity is widely recognized as it relates to the wild realm — rain forests, wetlands, tidal marshes, and prairies. Similarly, agriculture is a biological system with humans as a major source of selection pressure, and genetic diversity allows it to be both dynamic and stable.

Genetic diversity within a species is the presence of a large number of genetic variants for each of the species’ characteristics. For example, variation in the amount of feathering in chicken populations allows for some individuals to have featherless necks (as seen in the Naked Neck breed), which is an excellent adaptation for a hot environment, and for others to have thicker and looser feathers that trap insulating air (as seen in the Buckeye and Chantecler breeds), which is the perfect adaptation for a cold climate. This variability, resulting from small genetic differences among the breeds, allows the species to adapt to changes in the environment or other selection pressures.

The opposite of genetic diversity is genetic uniformity. Populations that have been intensely bred for certain characteristics over time, such as the Broad Breasted White turkey, may be well adapted to a specialized habitat or production system. Unfortunately, such specialization leads to genetic uniformity, resulting in inbreeding and a limited reserve of genetic options. This dramatically restricts the population’s ability to adapt to changing conditions, making it vulnerable, for example, to being wiped out by a disease outbreak or by climatic change.

The industrialization of agriculture has consolidated and specialized the once decentralized and integrated production of poultry into uniform systems of specialized mass production. Climate-controlled confinement housing, sophisticated husbandry and veterinary support, chemical additives, and heavy grain feeding have allowed breeders to ignore adaptation and other survival characteristics in favor of maximized production. While highly productive in exquisitely designed and supported environments, industrial stocks are unlikely to be able to adapt to any changes in their environment, such as a sudden restriction of external energy.

Genetic conservation must include varied breeds and types, especially those that have traits no longer found in industrial stocks. Failure to be far-sighted will eventually result in an agricultural crisis. Conservation of breed diversity must be actively pursued now, while the genetic diversity within the species is still available and relatively robust.

The conservation of rare breeds of poultry protects the broad genetic base found in each of the species of chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, and other poultry. This genetic diversity is imperative to meeting seven societal needs: food security, economic opportunity, environmental stewardship, scientific knowledge, cultural and historical preservation, ethical responsibility, and common ownership.

This Buff Orpington rooster is a member of a breed that is making a comeback. This resurgence is due to the efforts of conservation breeders, who recognize the many great traits of breeds that don’t perform well in an industrial system but do perform well in a barnyard setting.

Our culture is dependent on a stable food supply. Genetic diversity is the basis for responses to future environmental challenges, such as global warming, evolving pests and diseases, bioterrorism, and dwindling energy supplies. The Irish potato famine and the more recent outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease and avian influenza are examples of the vulnerability of genetic uniformity and industrial consolidation. Diversity is essential for long-term food security. Most people recognize the wisdom of not putting all of their eggs in one basket.

Rare breeds can offer economic opportunity by providing specialty products and services, such as free-range meat and eggs, colored eggs, and unusual feathers for fly-tying, crafts, decoration, and fashion that can be marketed into specialty niches. Specialty services might include pest control, recreational opportunities (the best fishing flies, for example, are produced with real feathers, rather than manmade materials), and product association for marketing purposes (such as Clydesdale horses with Anheuser-Busch’s Budweiser beer or Highland cattle with Dewar’s Scotch).

Genetic diversity can be used to develop new breeds to meet new needs. The specialization of the Leghorn for egg production and the Cornish-Rock cross for broiler production has been so successful that development of other breeds has not been considered recently. That does not mean that these specialized, ubiquitous breeds will always be able to provide for our needs.

Breeds that are rare today were important contributors to human welfare in the past and may possess characteristics that will be needed again to meet new or reemerging needs. The loss of these survival traits through negligence would be a tragedy for humankind.

Agriculture, including animal husbandry, is the chief interaction of humans with the environment. Genetic diversity within agriculture is essential for us to be able to adapt to environmental changes. It also allows us to improve the sustainability of agriculture by selecting breeds and production methods that require less input (of chemicals, energy, and so on) than what “modern” agriculture requires.

For example, poultry breeds that are adapted to do well on free-range forage require less input than those that are bred for mass production in contained, highly specialized environments. These sustainable practices are increasingly recognized for their economic and environmental value.

To fully understand the animal kingdom (to which we ourselves belong) requires the conservation of genetic diversity. Many rare breeds are biologically unusual because of the selection pressures applied in their evolution. Knowing about these pressures — climatic conditions and changes, diseases and parasites, reproductive differences, feed utilizations — and the way in which populations responded to them could provide useful information for improved agricultural production and human health.

Like artwork, architecture, language, and other complex artifacts, rare breeds inform us about the interests, skills, and values of our ancestors. Solutions to contemporary problems are often found in records of the past. Many traditional poultry husbandry techniques retain their usefulness today, but this once common wisdom is slipping away.

These living creatures also reflect our evolving relationship with the natural world. Rare breeds of domestic birds and other animals, as well as rare varieties of agricultural plants, represent the biodiversity that is closest to us and upon which we are most dependent.

Stewardship of the planet includes not only the many species of wild animals, plants, and habitats but also the domestic animals and plants that are part of the biological web of life. Those who appreciate the role of domesticated animals in providing services, food, and other products must believe that domestic animals have a right to continued existence, as do the wild species.

Domestic animals have been our partners for many centuries of coevolution and interdependence. They play a unique role in our culture; they are the first animals we learn about as children and are the subject of most nursery rhymes and children’s stories. We have a special obligation to protect them.

Rare-breed conservation keeps genetic resources in the hands of individual farmers and breeders around the world. This allows poultry to be freely owned, used, and bred by farmers and breeders without the barriers of patents and other corporate restrictions.

In contrast, consider the example of the seed industry, in which the concentration of genetic ownership and corporate patenting of hybrid and genetically modified seed varieties has resulted in a lack of public access to diverse seed supplies and the loss of many heirloom varieties. Widespread breed conservation can help prevent the same from happening to the poultry industry.

The adaptability and biological health of all domesticated species must be maintained to ensure that they continue to thrive in a wide range of environments and production systems without elaborate and expensive support systems.

The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) is the pioneer conservation organization for farm animals in North America. Its mission is the protection and promotion of over 150 breeds of cattle, goats, horses, asses, sheep, pigs, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys. Founded in 1977, the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy is a nonprofit membership organization working to conserve genetic diversity and save heritage breeds from extinction. For information about participating in breed conservation efforts, contact the ALBC; see Other Organizations for contact information.

Englishman Robert Bakewell took over his father’s Dishley Grange farm in 1760. While still quite young, Bakewell traveled throughout Europe studying farming practices of the time. Once the family’s farm became his, he began applying and documenting new ideas for irrigation, fertilization, crop rotation, and breeding.

Bakewell began his breeding program with the old native breed of sheep in his region of Leicestershire. At the time, both sexes were traditionally kept together in the fields. The first thing Bakewell did was separate the males from the flock. By controlling which rams were allowed to enter the flock for breeding, and when they were allowed to enter the flock, he found he could breed for specific traits.

The rams Bakewell selected for breeding were big, yet delicately boned, and had good quality fleece and fatty forequarters to respond to the market of the day, which favored fatty mutton. Soon Bakewell’s flock showed distinctive changes, and he named his new breed of sheep New Leicesters.

Bakewell’s approach to breeding was revolutionary. His efforts were based on a keen sense of observation and willingness to experiment, and his work provided the foundation upon which much of our understanding of breeding and genetics is based. Both Gregor Mendel (a monk whose 1865 paper on inheritance in peas is considered to be the first scientific research on the topic of genetics) and Charles Darwin referred to Bakewell’s efforts in developing their theories.

We often hear debates over the influence of genes on everything from behavior to health — the nature-versus-nurture debate. The truth is, most traits are influenced by both nature and nurture.

For instance, birth weight and growth rate are both definitely dependent on the genetic material passed down from Mom and Dad, but they are also highly influenced by environmental factors such as diet and weather. An animal can have top-of-the-line breeding and perform poorly if not given proper care, or an animal that has poorer genetic material can do really well when given excellent care (think Sea Biscuit, the knock-kneed poor-excuse-of-a-racehorse that captured the world’s fancy and the Triple Crown when the right owner, trainer, and jockey gave him their best).

A small group of traits, like the color of plumage, are controlled primarily by heredity; however, even these can be affected by extremes in environmental factors. To give just one example, black-feathered animals that have inadequate amounts of the trace minerals zinc and copper in their diet may exhibit a coppery tinge.

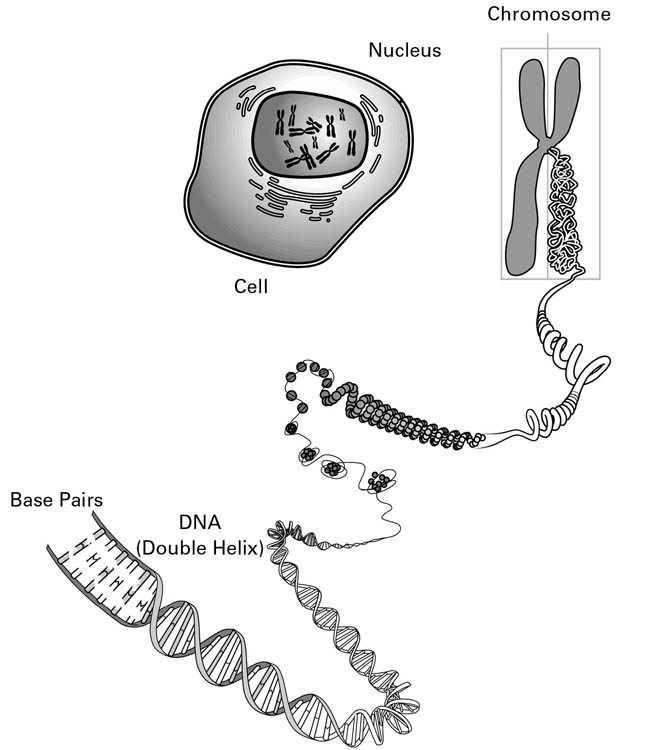

If you haven’t given much thought to biology since high school, then a quick review of some of the principles may be helpful. All living things are made up of cells, and with the exception of some types of single-cell organisms (such as blue-green algae), every cell contains a nucleus. Stored within the nucleus is the genetic data that defines the creature, be it a microscopic organism or the incomprehensible teenager who works at the movie rental store. This genetic data is carried on chromosomes.

There are some important points to remember about chromosomes: Different species have different numbers of chromosomes. Chromosomes come in pairs in all cells of the body except the egg and sperm cells. Each egg and sperm cell has only half of the pair of chromosomes; when the egg and sperm combine to create a zygote, or fertilized egg, the two halves combine to create a complete pair of chromosomes.

All but one pair of chromosomes are identical in shape and proportion, though they do vary in size; these pairs are called autosomes. The pair that is distinctly different from the rest is the pair that determines the sex of the animal.

A turkey, for example, which has a total of 40 chromosome pairs, has 39 pairs of autosomal chromosomes that are the same shape and share the same proportions within each pair. It also has one pair of chromosomes that are clearly different, and these are referred to as the sex chromosomes.

In poultry, the letters Z and W designate the sex chromosomes, with the male having two Z chromosomes (written ZZ), and the female having a Z and a W chromosome (written ZW). (In mammals the sex chromosomes are designated by the letters X or Y, with the female combination written as XX and the male as XY.)

Each chromosome is made up of a single molecule of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), but the DNA molecule can be parsed out into still smaller units called genes. DNA molecules typically have hundreds or even thousands of genes. Scientists estimate that most mammals and birds have a total complement of twenty thousand to thirty thousand genes, depending on the species, and this total complement is called the genome.

Scientists around the world are busy trying to map the genome for humans and other species, including poultry. This research is yielding some interesting findings. For instance, chickens and humans share over 60 percent of the same genes, yet there are significant divergences in the DNA sequences along those genes. Scientists say this information will help them better understand how the evolutionary tree of birds and mammals split over millions of years.

|

SPECIES |

NUMBER OF CHROMOSOME PAIRS |

TOTAL NUMBER OF CHROMOSOMES |

|

Human |

23 |

46 |

|

Chicken |

39 |

78 |

|

Turkey |

40 |

80 |

|

Duck |

40 |

80 |

Genetic information is contained on chromosomes, which are made up of a DNA molecule and reside within the nucleus of the cell. DNA consists of thousands of genes, and each parent contributes one-half of the genetic code to its offspring.

DNA takes the form of a double helix (picture a very long, though submicroscopic, ladder that twists as it extends upward). Four compounds, adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C), are the primary chemical building blocks of the DNA molecule. Each rung of the ladder is made up of two of these compounds. The A always shares a rung with the T, and the G always shares a rung with the C. The rails, or sides of the ladder, are made up of a sugar molecule (deoxyribose) and a phosphoric acid molecule. The average gene is thought to occupy an area of about 600 pairs, or rungs, of these DNA building blocks.

As a cell divides and multiplies into two cells, the DNA molecule separates down the middle of the ladder, like a zipper opening up. Each new cell receives one side of the helix. The designated pairings of A to T and G to C serve as a template for rebuilding the molecule from chemical compounds within the cell.

Traits ranging from color to size, hardiness, and personality are most often influenced by more than one gene. When multiple genes are responsible for a trait, one may be epistatic over other genes, meaning that it will suppress them and thus control how the trait manifests.

Over thirty genes influence color in chickens, which helps to explain the extraordinary array of feather colors and patterns, such as the spangled pattern in this bantam Old English hen.

Each gene is made up of a pair of “alleles,” or gene forms, which are typically designated by a letter, or by letters and symbols. Every gene has at least two potential alleles, or variations, but many have multiple alleles. Some of these alleles are dominant over others, acting like an on-off button that activates certain genetic manifestations. Others act like a dimmer switch on a light, altering the intensity of a trait. In other words, how a trait actually shows up depends on which alleles are present on the gene. By convention, capital letters are generally used to represent dominant alleles and lowercase letters to represent recessive ones.

So far, geneticists have identified over thirty different genes that can come into play in determining the color of poultry plumage, eyes, earlobes, beak, and legs and at least thirteen genes that contribute to eggshell color. It is thanks to this great variation in gene and allele combinations that we see such an extraordinary range of colors in our humble barnyard birds and their eggs.

Let’s use one of these color genes, the melanocortin (MC) gene, as an example. Also known as the “extended black” gene, the MC gene has eight allele forms, which are designated by E, ER, e+, eb, ewh, es, ebc, and ey. These alleles control black, brown, red, and yellow pigments in the plumage, as well as speckling.

The order of dominance among the MC alleles is generally accepted as E > ER > e+ > eb > ewh > es > ebc > ey. For example, the E form is associated with solid black plumage, and the e+ with black-breasted red plumage (called the “wild type” because it is similar to the coloring of the Red Jungle Fowl). If the pair of genes shows up as Ee+, the dominant E results in solid black, but if the e+e+ combo happens to show up, the black-breasted red feather pattern is seen.

Rose comb

Single comb

Pea comb

Walnut comb

Comb type is usually controlled by just two genes, the rose and the pea gene. The Hamburg rooster (top) has at least one dominant R allele on the rose gene, and no dominant P alleles on the pea gene. The Andalusian rooster (2nd from the top) shows the most common comb, the single, which results when no dominant R or P shows up on either gene. The Ameraucana rooster (3rd from the top) has a dominant P on the pea gene. The walnut comb, as seen on the Orloff rooster (bottom) has at least one dominant allele on both the rose and pea genes.

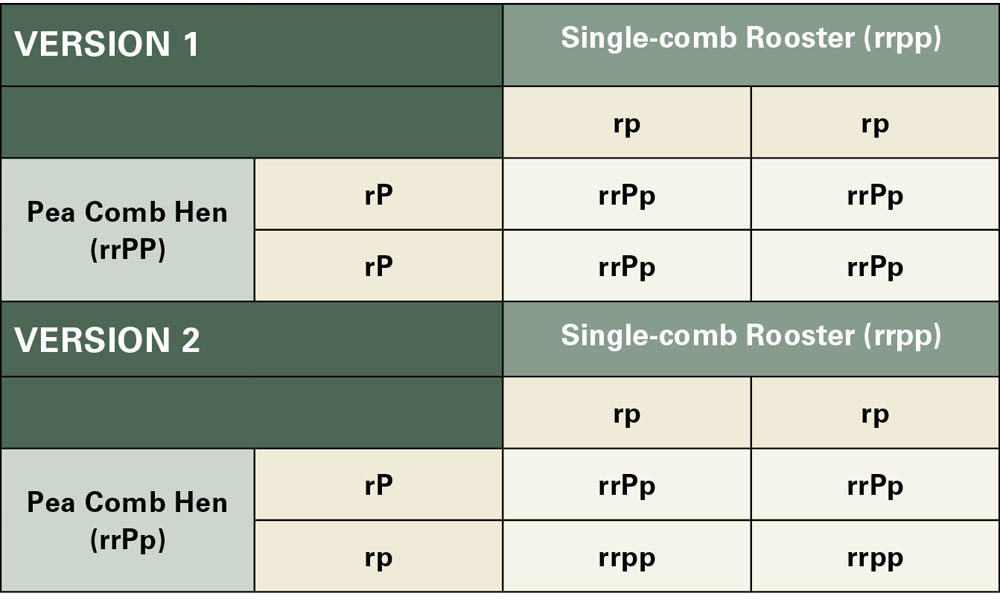

Genes are passed from one generation to the next in a fairly orderly manner. Just as DNA is supplied by both parents, so are the alleles that adjust traits. Since the comb type is primarily controlled by just two genes (the rose, or R, gene and the pea, or P, gene) and each has just two alleles (R and r for the rose and P and p for the pea), we will use it to see how traits actually pass from one generation to the next.

For the two genes, there are essentially nine combinations (RRPP, RRPp, RRpp, Rrpp, RrPp, RrPP, rrPp, rrPP, and rrpp). The majority of chickens have a single comb — the upright type of comb with spikes that most people visualize when they picture a rooster cock-a-doodle-dooing. It is the default when neither a dominant rose allele (R) nor a dominant pea allele (P) is present; in other words, when the combination of the two genes is rrpp.

Birds that have a rose comb have at least one dominant rose allele but they don’t have a dominant pea allele (RRpp or Rrpp); birds with a pea comb have at least one dominant pea allele but they don’t have a dominant rose allele (rrPP or rrPp); and birds with a walnut comb have both a dominant rose allele and a dominant pea allele (RRPP, RrPp, RrPP, or RRPp).

The chart to the right shows the likelihood of outcomes for a pea-comb hen and a single-comb rooster, depending on the allele combinations that the rooster and hen have.

Although most of the time genetic messages are passed from parents to offspring correctly, sometimes they are not. When chromosomal material is lost or rearranged during early development, the most common outcome is death of the developing embryo.

As a rule, most chromosomal problems are attributable to a problem during formation of the egg or sperm or during the combining of the sperm and egg. Some minor losses or rearrangements may not be lethal, but they often cause continuing health problems such as slow and abnormal growth or infertility.

When inherited from both parents, some alleles (referred to as “lethal alleles”) result in death or serious health problems. One example of a lethal allele is associated with the ear tuft gene in Araucana chickens. Araucana chicks that are homozygous, or that have the same form on both halves of the gene for ear tufts (EtEt), usually die in the egg somewhere between day 17 and day 19 of incubation. Araucanas that survive have the (Etet+) combination.

Two hens with a pea comb, when mated with a single-comb rooster, may not have chicks with the same comb types, depending on the allele combinations in the hen. In version 1, all of the chicks will be born with a pea comb, but in version 2, roughly half of the chicks will be born with a pea comb and the other half will be born with a single comb.

Some allele combinations, referred to as “lethals,” result in death or serious health problems. The dominant Et allele of the ear tuft gene, which gives the Araucana its ear tuft feathers, is such a lethal. Birds that have the EtEt combination usually die in the egg.

Breed. Historically, breeds were developed and recognized as predictable packages of characteristics. Juliette Clutton-Brock, a historian, biologist, and leading expert on the domestication of animals, defines the term breed as “a group of animals with a uniform appearance and behavior that distinguishes them from other groups of animals of the same species. When mated together they reproduce the same type.” That is, breeds breed true.

Domesticated Species. A species that has been brought into a codependent and relatively “tame” relationship with humans that has resulted in unique biological changes within the species. Many individual wild animals can be tamed, but of the thousands of species that share the earth with us, fewer than 50 have been truly domesticated.

Genotype. The complete genetic makeup of an individual as described by the arrangement of its genes. The genotype of individuals within the same breed will be similar but unique.

Phenotype. The physical characteristics or behaviors of an animal that can be observed or tested for, such as feather color, aggressiveness, or blood type.

Variety. A subdivision within a breed that breeds true for distinct characteristics, such as color or comb type.

The Serama (a Serama rooster is shown) is a relatively new breed in North America. In its native Malaysia, the breed is said to have thousands of color varieties.

The husbandry of poultry isn’t particularly challenging, but selective breeding for maintaining traits is. One of the challenges that arises is caused simply by the genetic complexity that exists within the gene pool of domesticated birds. Another is caused by the social network that birds live in: Chicken, duck, and turkey flocks, for example, have a distinct hierarchy, or pecking order, and introducing new birds (or new bloodlines) to the flock usually results in fighting and a reorganization period. And geese and swans form pair bonds, taking particular mates that they keep for long periods.

Selections generally need to be made for multiple traits. Physical conformation, general health and soundness, reproductive qualities (including broodiness and mothering capabilities), color, utility qualities (such as meat or egg production), hardiness, foraging ability, adaptability to confinement, and temperament are just some of the traits that need to be considered when planning a breeding program. Successful breeders stay focused on the traits they are trying to maintain or improve and make breeding decisions systematically.

There are several approaches to breeding. These include single mating, where one specific male is bred to one specific female in a pen separated from the rest of the flock; line mating, where closely related birds are bred, such as a rooster to his daughters; multiple-sire mating with selection, where groups of three to five males are cycled through a segregated flock of females and the best offspring from the multiple matings are selected; and distinct-line breeding, where unrelated lines are crossed in genetically limited groups of birds to improve vigor. Each option has its own benefits, depending on the goals of the breeder.

Breeders make breeding selections based on desired traits. Here, Silkie chicks are already beginning to show the trait their breed is best known for — the silky feathers that cover them from head to toe.

Breeding to meet specific colors or physical characteristics can often be a challenge. For example, meeting the standard for the Japanese bantam’s conformation is not something many neophyte breeders do well.

Probably the best way to learn the breeder’s skills is to be mentored by a poultry breeder who has been at it for some time. Over the years I have found serious poultry keepers to be generous souls who love to share their knowledge with those that are new to the endeavor (see the resources section to find out how to meet these folks). Your mentor will reinforce these three keys to success:

If there are no knowledgeable breeders near you, the ALBC has published two excellent books: A Conservation Breeding Handbook, by Dr. Phillip Sponenberg and Carolyn J. Christman, and Managing Breeds for a Secure Future: Strategies for Breeders and Breed Associations, by Dr. Phillip Sponenberg and Dr. Donald E. Bixby.

No matter where you live, you can probably keep poultry on a small scale. Even large cities usually allow homeowners to keep a few hens. Birds are fun, and they supply real value, from eating pesky bugs to keeping the family in eggs. Let this book be your guide to the breeds and do get started with poultry; it is a decision you won’t regret.

This bantam White Leghorn hen is the result of generations of breeding for outstanding ability as a layer.

As you read the bird descriptions in later chapters, you will see for each a category labeled Conservation Status. This category uses designations established by the ALBC for its Conservation Priority List. These designations (listed below) are based on the estimated number of breeding birds and breeding flocks, as determined by a census and other research.

Critical. Fewer than 500 breeding birds in the United States, with five or fewer primary breeding flocks (50 birds or more), and globally endangered.

Threatened. Fewer than 1,000 breeding birds in the United States, with seven or fewer primary breeding flocks, and globally endangered.

Watch. Fewer than 5,000 breeding birds in the United States, with ten or fewer primary breeding flocks, and globally endangered. Also included are breeds with genetic or numerical concerns or limited geographic distribution.

Recovering. Breeds that were once more threatened and have now exceeded “Watch” category numbers but are still in need of monitoring.

Study. Breeds that are of interest but either lack definition or lack genetic or historical documentation.

Not Applicable. The ALBC has not listed this breed on its Conservation Priority List. This could be due to a number of reasons: the breed has sufficient breeding birds and flocks; it was never established with continuous breeding populations in North America; the foundation stock is no longer available; or the global population is sufficient to protect a breed that isn’t traditionally important in North America.