Three

NEW YORK

CENTRAL SYSTEM

The New York Central System (NYC) was Cleveland’s dominant railroad. The primary ancestors of the NYC in Cleveland were the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway (Big Four), and the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad (LS&MS).

The LS&MS, incorporated April 6, 1869, resulted from a series of mergers in the 1850s and 1860s. By August 16, 1869, it controlled a Chicago-Buffalo, New York, route via Cleveland and Toledo, Ohio, and Erie, Pennsylvania. Cornelius Vanderbilt and his New York Central and Hudson River Railroad (NYC&HR) gained stock control of the LS&MS in August 1877. The LS&MS maintained its own identity until merging with the NYC&HR on December 22, 1914.

Cleveland’s first intercity railroad, the CC&C, had merged with the Bellefontaine Railroad on May 16, 1868, to form the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis Railroad (CCC&I), also known as the Bee Line.

Vanderbilt’s son, William H. Vanderbilt, had invested in the first Big Four—the Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis & Chicago Railroad (CIStL&C)—which had formed on March 6, 1880. By the time of the CCC&I merger with the CIStL&C in June 1889, the Vanderbilts had stock control of the Big Four. The NYC leased the Big Four on February 1, 1930.

The LS&MS held ownership stakes in two other railroads that built routes in Cleveland. It held all of the stock in the Cleveland Short Line Company, incorporated on November 24, 1902, to build between Collinwood Yard and Rockport on Cleveland’s southwest side. The route opened between Rockport and Marcy (9.73 miles) on February 24, 1910, and between Marcy and Collinwood (9.91 miles) on July 1, 1912.

The LS&MS was a half owner with the Pennsylvania Railroad of the Lake Erie and Pittsburgh Railway (LE&P), incorporated on April 29, 1903, to build between Lorain and Youngstown. The only portion of the LE&P ever built was a 27.79-mile section between Marcy and Brady Lake Junction on the PRR. The PRR did not use the LE&P, but the NYC used it for freight service only between Cleveland and Youngstown. East of Brady Lake Junction, the NYC exercised trackage rights on the PRR and B&O to reach Youngstown.

Commercial passenger service on Lake Erie dates to the early 19th century. The first steam-powered boat was the Walk-In-The-Water, built in 1818. In 1869, the Detroit & Cleveland Steam Navigation Company began scheduled overnight service between the two cities. The Cleveland & Buffalo Transit Company was organized in 1885 to provided service between its namesake cities. The C&B ultimately also operated side-wheelers to Toledo, Cedar Point, and Put-in-Bay. Both photographs on this page show an NYC train at the Cleveland Lake Erie docks in about 1900. The D&C and C&B began using a new dock in 1915 that was located at the foot of East Ninth Street. This facility was served by a streetcar line. The C&B ceased operations in 1939 after going bankrupt. The D&C continued in operation until 1951. Both companies lost business as the automobile grew in popularity. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

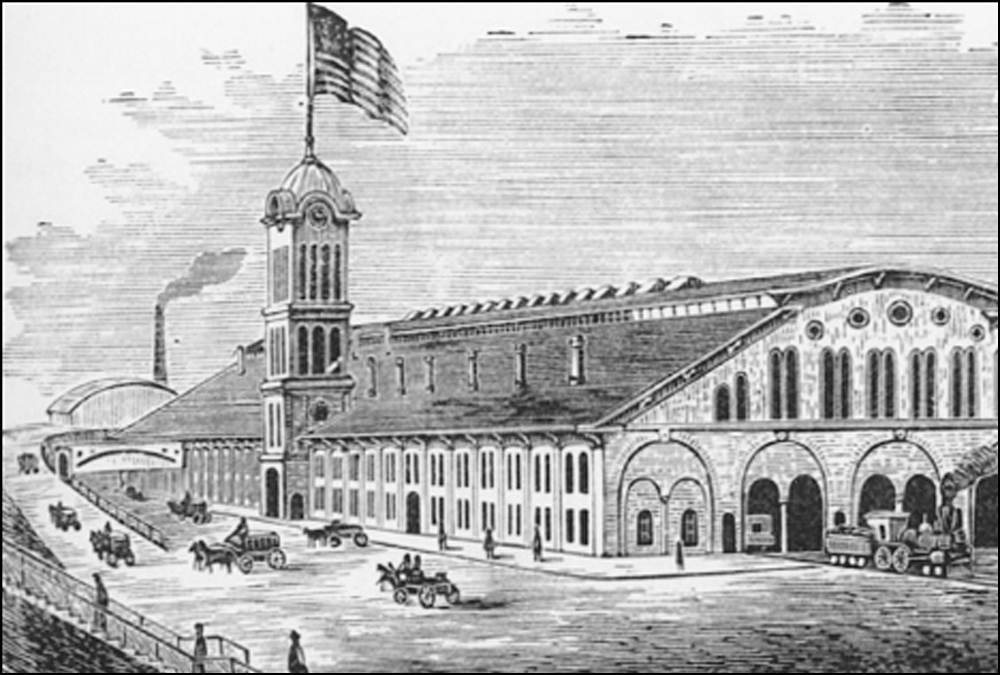

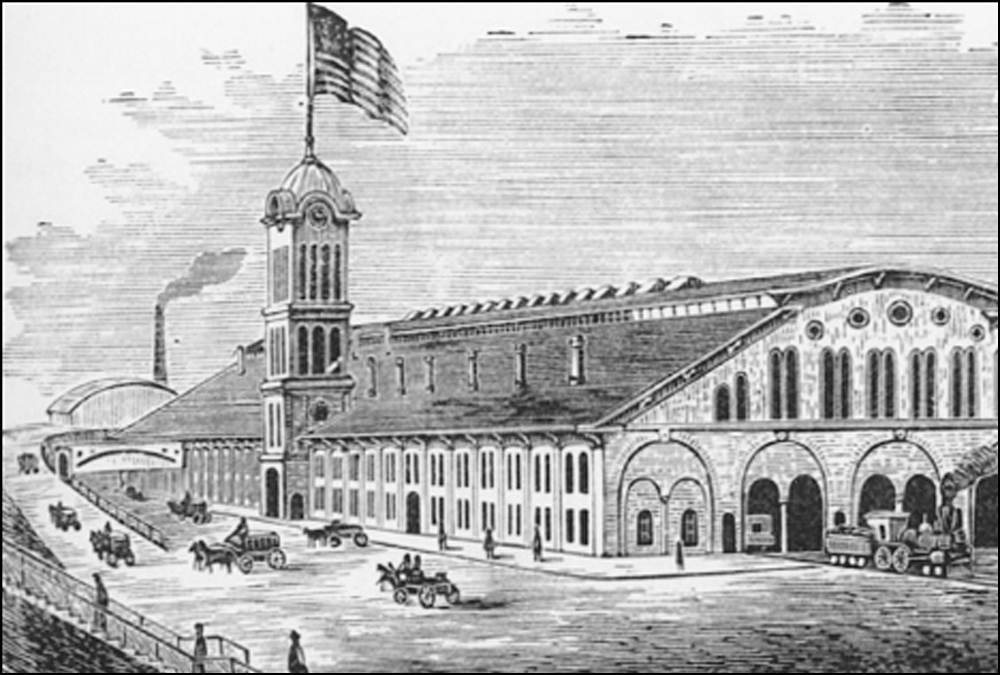

Until the construction of a Union Depot in 1853, each railroad that served Cleveland had its own passenger station. Cleveland’s first Union Depot was destroyed by fire in 1864, and a second Union Depot was built at a cost of $475,000 near the site of the first station. Dedicated on November 10, 1866, the second Union Depot measured 603 by 108 feet and was, at the time, the largest building in the country under a single roof. The station was constructed of Berea sandstone and was among the first buildings to use structural iron. Its signature feature was a 96-foot clock tower on its southern facade. The image above of the second Union Depot was made from a wood engraving. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The LS&MS had two Cleveland-Toledo routes. The Northern Division ran via Sandusky and Elyria. The Southern Division used the Big Four to Grafton; there, LS&MS trains gained their own tracks, operating via Oberlin and Norwalk before joining the Northern Division at Milbury. In 1866, a line was built from Elyria to Oberlin. The route between Oberlin and Grafton was removed, and use of the Big Four ceased. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Wood was commonly used in the construction of railcars in the late 19th and early 20th century because lumber was plentiful and there was an abundance of workers with woodworking skills. Though metal cars might last longer and be fireproof, cars built with wood were less expensive. By the 1930s, railcars were made primarily of metal with wood sheathing, a practice that had ended by the 1950s. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

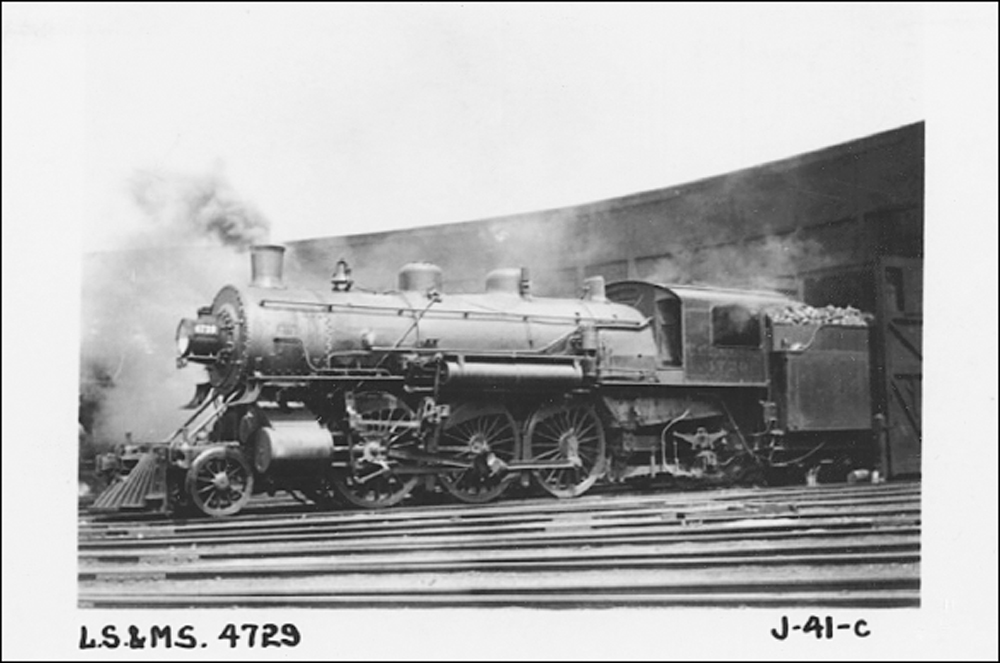

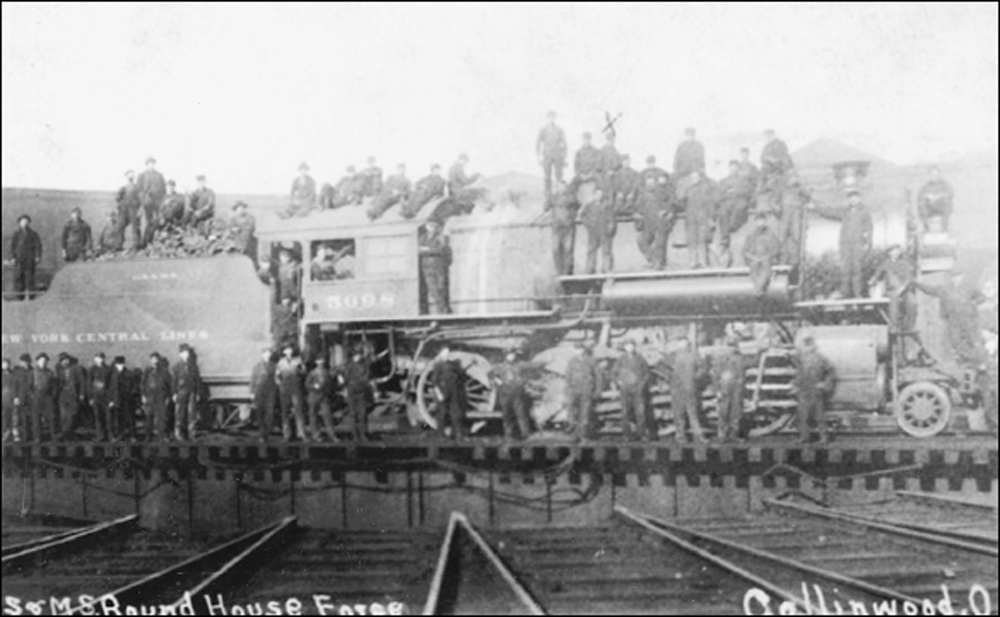

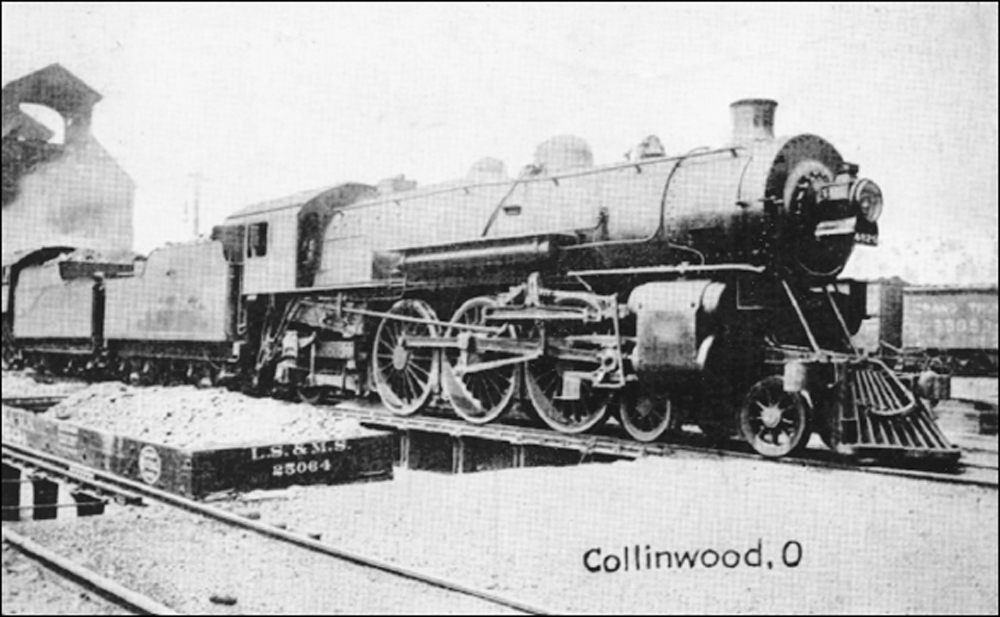

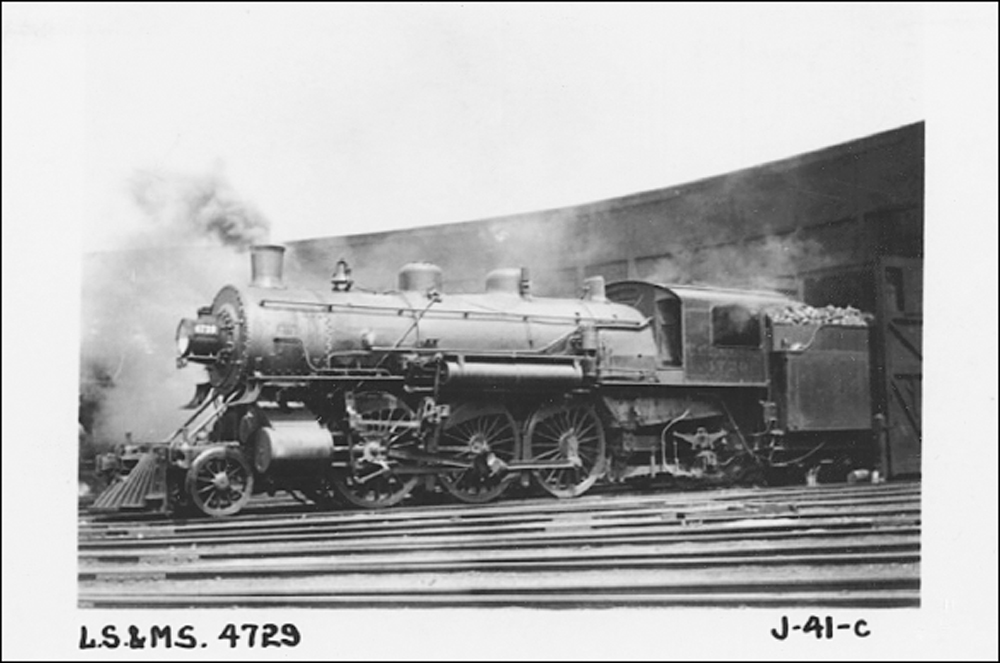

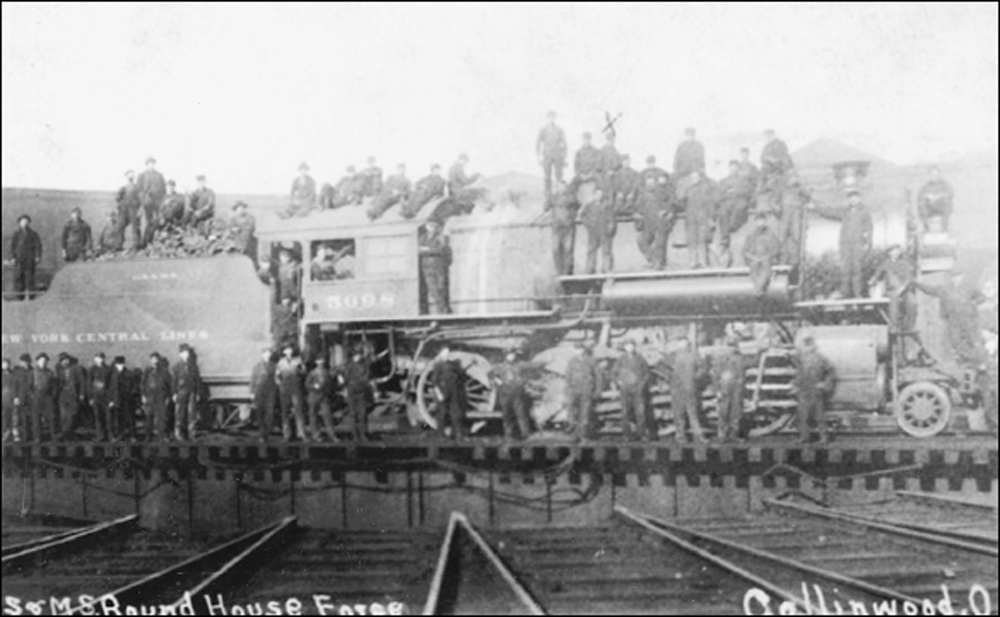

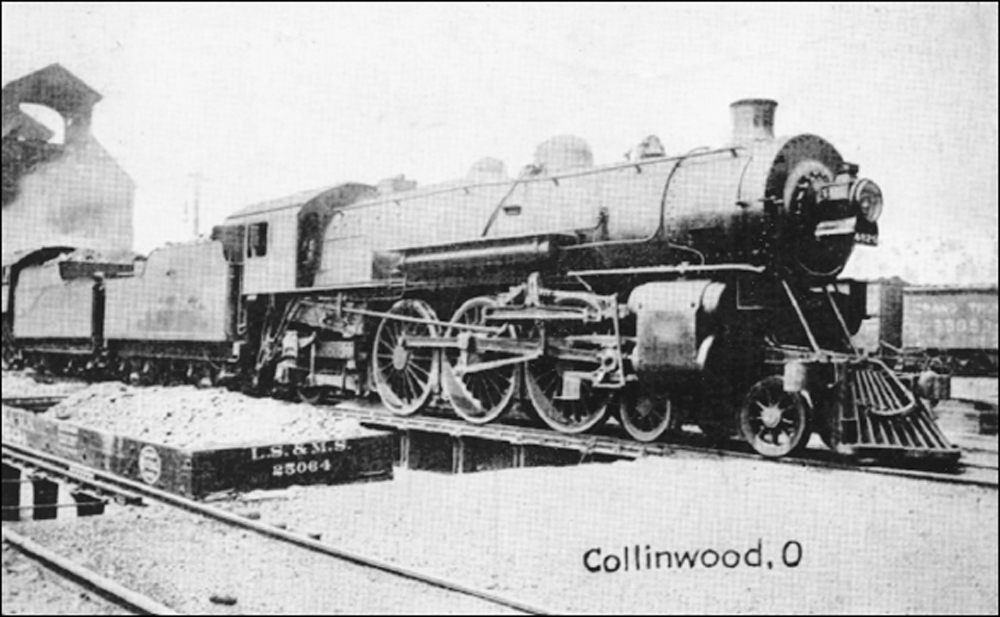

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, travelers often sent postcards to family and friends to show where they had been or provide examples of what could be seen in their own communities. Railroad scenes were popular subjects for postcards, particularly during the first two decades of the 20th century when railroad travel was at its peak. Railroad postcards featured everything from stations to landmarks to railroad workers. It was common around the turn of the 20th century to pose shop workers on a locomotive, as seen in the image above on the LS&MS at Collinwood Yard in Cleveland. Sometimes, the image would simply be of one or more locomotives, as demonstrated in the image below of two LS&MS locomotives that were posed tender to tender at Collinwood Yard. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

NYC called its 4-8-2 steam locomotives Mohawks, whereas other railroads used the Mountain-type designation. NYC used the Mohawk name because it emphasized that it was a railroad route that ran at water level. The NYC acquired its first Mohawk in 1916 for use on fast freight trains; it eventually owned 600 of them. L3-class No. 2956 is shown pulling a freight in Cleveland on May 1, 1938. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The L3a- and L4a-class NYC Mohawks were built without smoke deflectors and later had them added. L3-class No. 3021 is shown headed westbound with a caboose up west Park Hill at Bulkey Boulevard on March 3, 1946. An L3a-class locomotive was designed to haul freight or passenger trains. The NYC had 65 locomotives in this class, all built in 1940 by Alco.

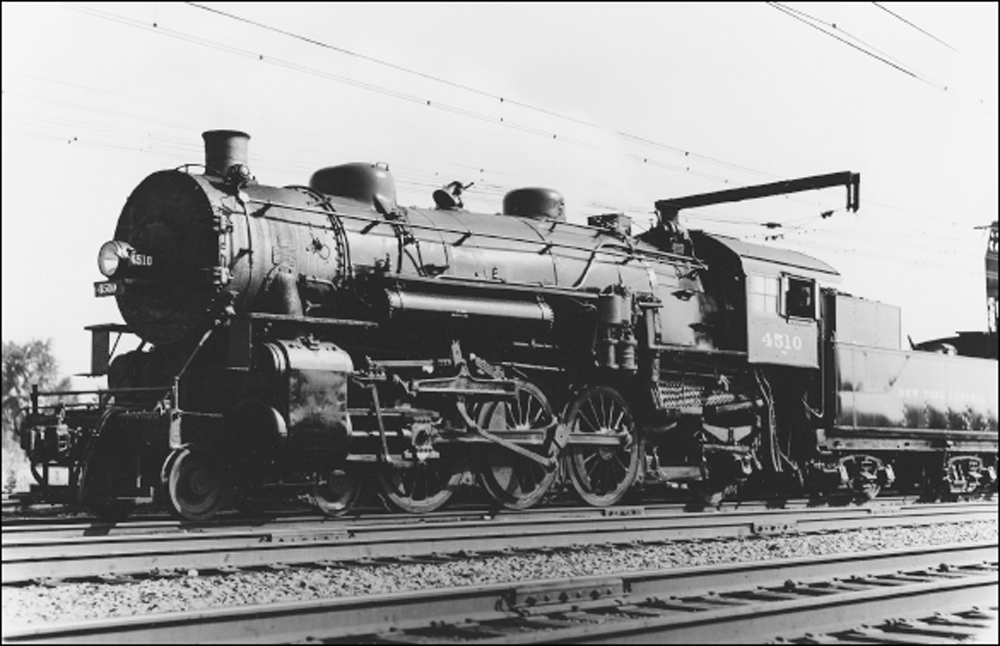

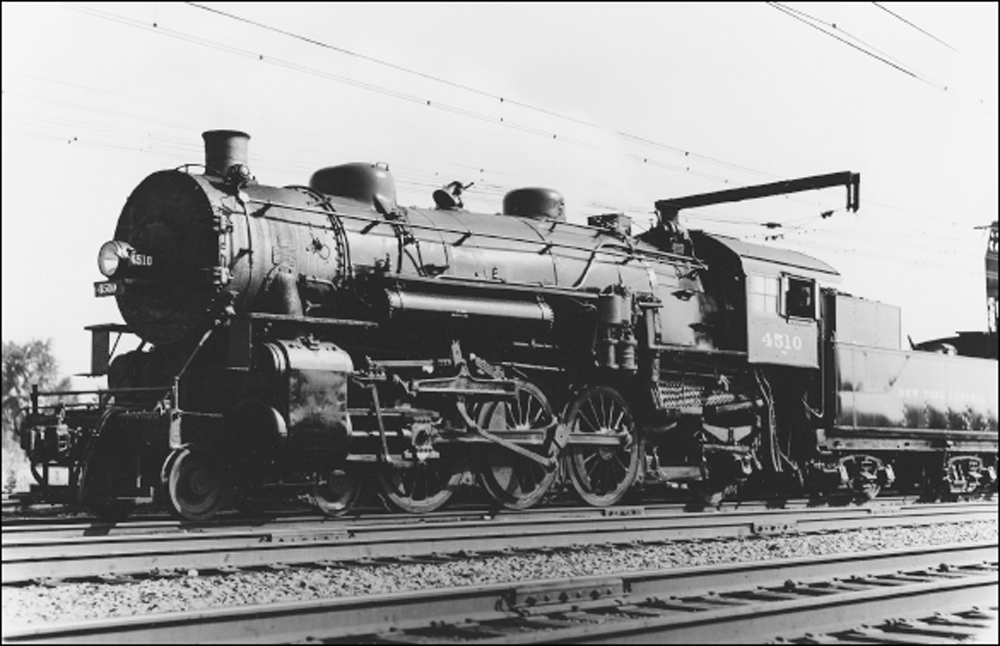

The 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotive was the most pervasive locomotive used in the United States and Canada during the first half of the 20th century. The first Pacific was built in 1902, and by 1930, about 6,800 of these locomotives had been built for North American service. The NYC had more than 1,000 Pacifics in 26 classes. In the photograph above, No. 4912 reposes at a service facility on May 1, 1938, in Cleveland. This locomotive was one of 35 K5-class Pacifics on the NYC roster. These were the largest Pacifics on the roster and were built for express passenger service. They were built by Alco in 1924 and were the last Pacifics produced for the NYC. In the photograph below, No. 4510 is shown in Cleveland in an undated photograph. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Refrigerated boxcars, often called reefers, enabled railroads to carry meat and produce over long distances. Reefers commonly operated in dedicated trains that had expedited schedules that, in some instances, gave them priority over passenger trains. Many reefers used ice to provide refrigeration, and these trains had to stop at designated points to receive new ice. A NYC reefer train is shown in Cleveland in an undated photograph. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

With 1,350 Mikado-type locomotives in the system, the NYC was the nation’s largest operator of the 2-8-2 engine. First built in the early 1900s, most of these locomotives had entered service by the 1930s. No. 95, pictured here in an undated photograph at Cleveland, was an H10a-class locomotive. The NYC had 57 of these, all built between 1922 and 1923 by Alco. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

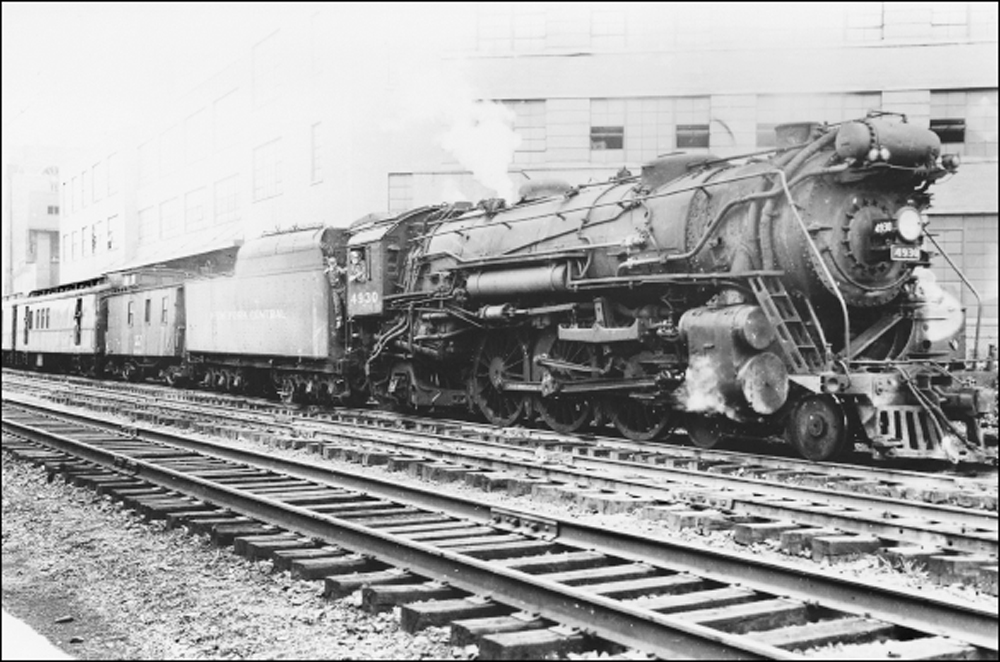

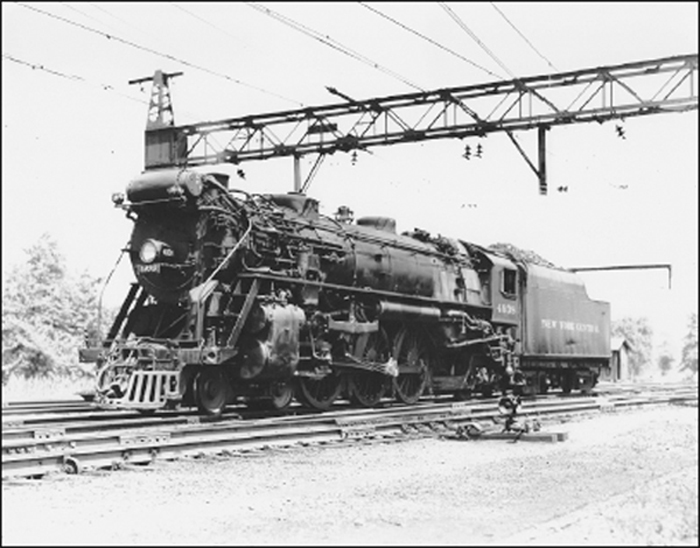

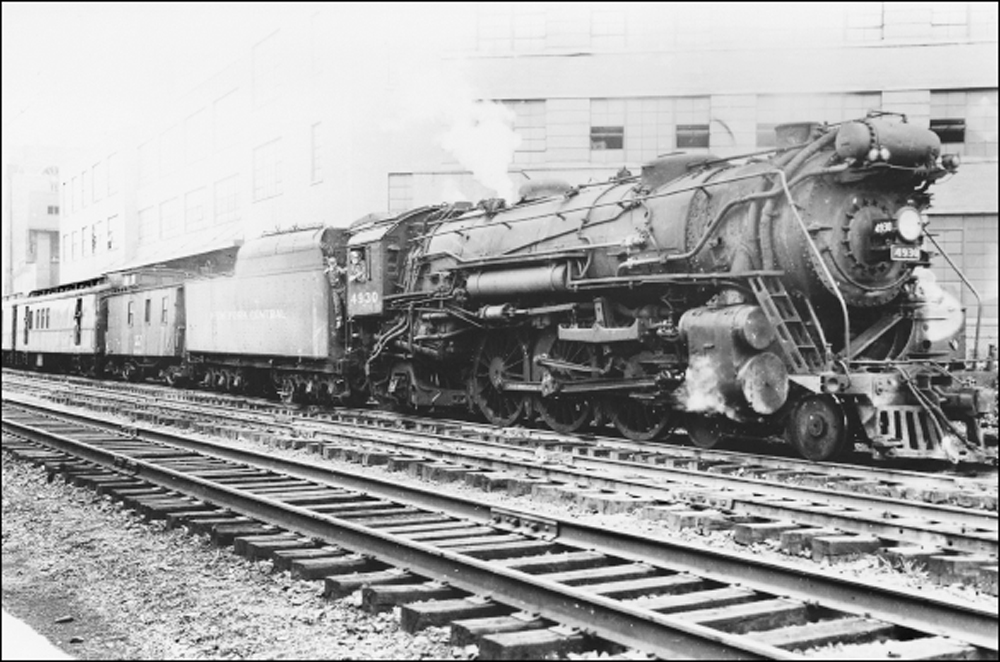

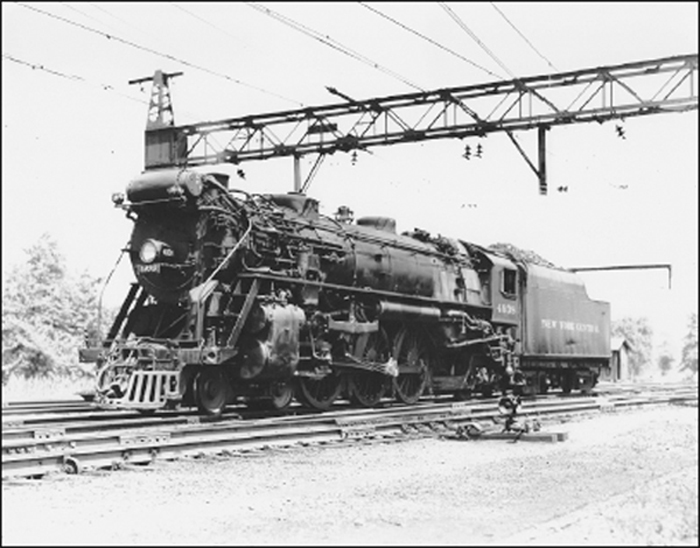

By 1900, the NYC’s Lakefront Line was clogged with freight and passenger traffic. To reduce congestion, the Cleveland Short Line Railway constructed (between 1910 and 1912) a double-track line between Collinwood and Rockport that bypassed downtown. Another congestion-reducing step was building a passenger terminal on Public Square. Backed by the Van Sweringen brothers, the proposed CUT received support from A.H. Smith, a regional director of the United States Railroad Administration (USRA), which controlled the nation’s railroads during World War I.O.P. Van Sweringen wanted to extend the tracks directly north from CUT to the lakefront, but Smith rejected that because it would not reduce congestion. He favored building a new route that crossed the Cuyahoga River on a high-level bridge. These images both show NYC K–class Pacifics built in 1924 by Alco. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Alco built 265 of the NYC’s Hudsons, while Lima built 10. The first was delivered on February 14, 1927, and the last arrived in 1938. NYC subsidiary Michigan Central Railroad was assigned 30 of the locomotives, while 30 went to the Big Four, 20 to the Boston & Albany Railroad, and 195 to the NYC proper. No. 5430 and its tender were photographed in Cleveland on May 21, 1939. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The LE&P never hosted passenger trains and was used only by the NYC even though the PRR had an ownership stake in it. Most of the LE&P was abandoned by PC in the early 1970s. A small portion remained in place near Twin Lakes to serve a sand company. Here, a westbound NYC train has just entered the LE&P at Brady Lake in March 1957. (Photograph by Bob Redmond.)

The early 1950s saw a mixture of steam and diesel power on NYC trains in Cleveland. There were still many steam locomotives operating on the former Big Four, but their numbers were steadily dwindling. A westbound freight pulled by a 4-8-2 Mohawk locomotive is pictured here at West Twenty-fifth Street in Cleveland, passing the Federal Coal yard. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC was not among the earliest railroads to forsake steam for diesel power, but once it began to dieselize, it moved quickly. It replaced steam locomotives with diesels from east to west, and the system east of Buffalo, New York, was converted by fall 1953. In this image, three Hudson-type locomotives sit silently on the dead track at Collinwood Yard on June 19, 1956, soon to meet the scrapper’s torch. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

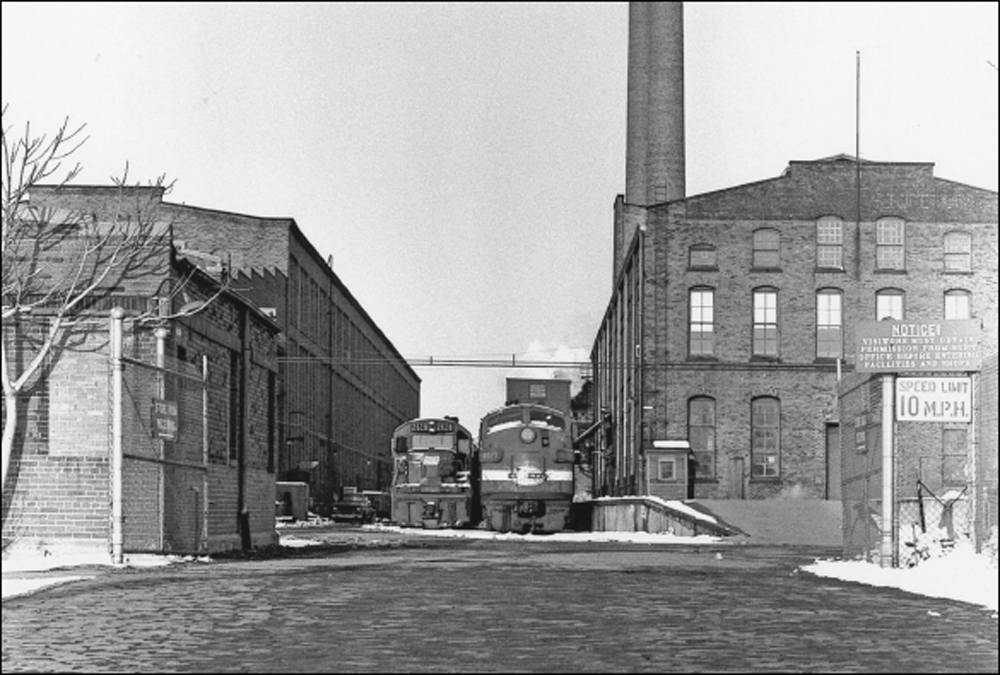

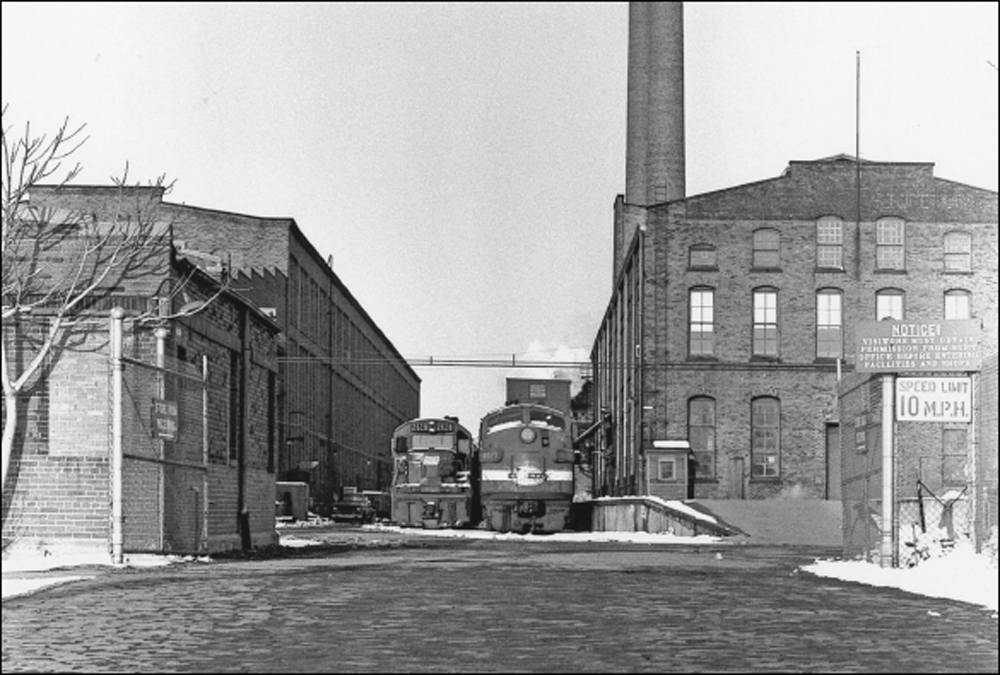

Above, a trio of F-series diesel-electric locomotives built by EMD sits at the service facility in Collinwood Yard on July 27, 1950. These locomotives were primarily used in freight service, and each was rated at 1,500 horsepower. The locomotives are, from left to right, No. 1633 (an F3A), No. 1609 (an F3A) and No. 1674 (an F7A). Altogether, the NYC had 341 F units, the first of which it acquired in 1944 when it ordered eight FT-model locomotives. The NYC spent two years studying the performance of the FTs before it ordered any more freight diesels. Below, a crewmember watches F7A No. 1836 and a B unit maneuver at the Collinwood shops. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC’s EMD E-series diesels were used in passenger service throughout the system. The first of these that the NYC ordered were 50 E7 locomotives that it acquired between 1945 and 1949. In the undated image at right is E7A No. 4002 with the engineer waving for the photographer. NYC’s E7 fleet included 36 cab and 14 booster locomotives. This model of locomotive generated 2,000 horsepower. In the undated photograph below, E8A Nos. 4044 and 4043 are seen at Cleveland. NYC ordered 60 of these locomotives between 1951 and 1953. Although intended for passenger service, some E units were assigned to Super Van intermodal trains. Some NYC E units continued to pull passenger trains for PC and, later, for Amtrak. Nos. 4043 and 4044, both built in September 1951, became Amtrak Nos. 260 and 261 respectively. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC bought diesel locomotives from six manufacturers, including Alco, which had built most of NYC’s steam locomotives. NYC’s all-time diesel roster, including subsidiaries and affiliated railroads, listed 2,751 locomotives. The NYC usually assigned diesels to designated pools, basing them at or near a home repair terminal. With 770 units, the NYC had one of America’s largest rosters of Alco diesel locomotives. Ultimately, the NYC had more EMD and GE locomotives than Alco products. Among the Alco locomotives that the NYC used were 30 PA/PB passenger locomotives. Shown above are PA-1 No. 4204 and another unidentified locomotive pulling a passenger train. The NYC often assigned these passenger diesels to Cleveland-Pittsburgh trains. It also ordered 35 Fairbanks-Morse C-liner cab units for passenger service, including No. 4505, shown with a mate in Cleveland in an undated photograph below. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC owned just 99 locomotives built by Baldwin Locomotive Works. One of those models was the RF16, which had the nicknames “shark” or “shark nose.” Most of the NYC’s RF16 locomotives were assigned to former Big Four routes in Ohio and Indiana. Originally numbered in the 3804-to-3821 series, the sharks were later renumbered 1204 to 1221. This NYC freight train includes work-train equipment and a crane. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

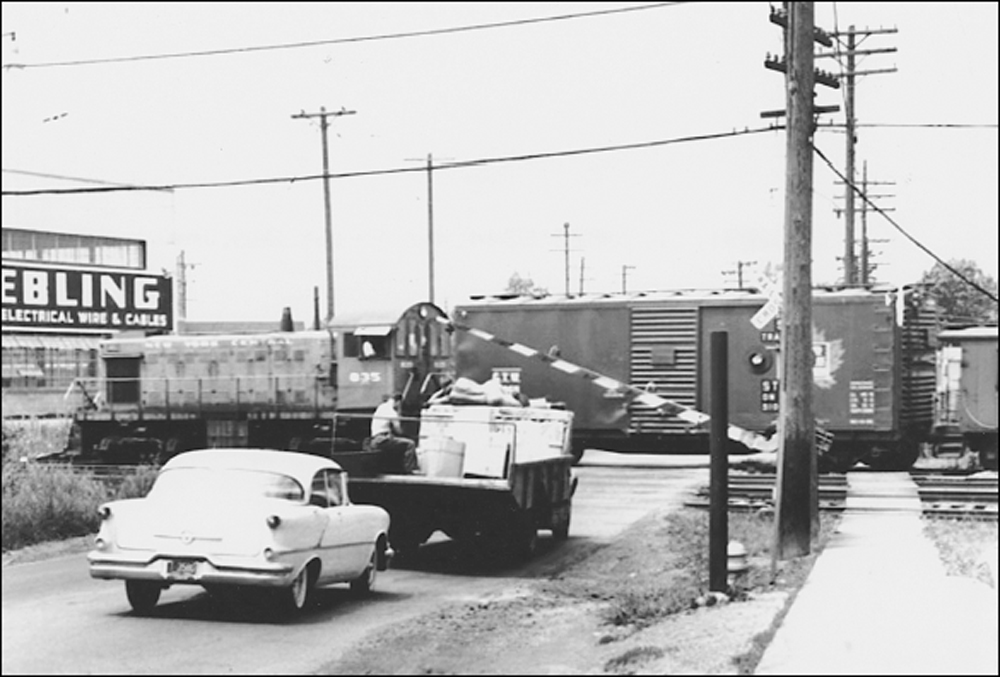

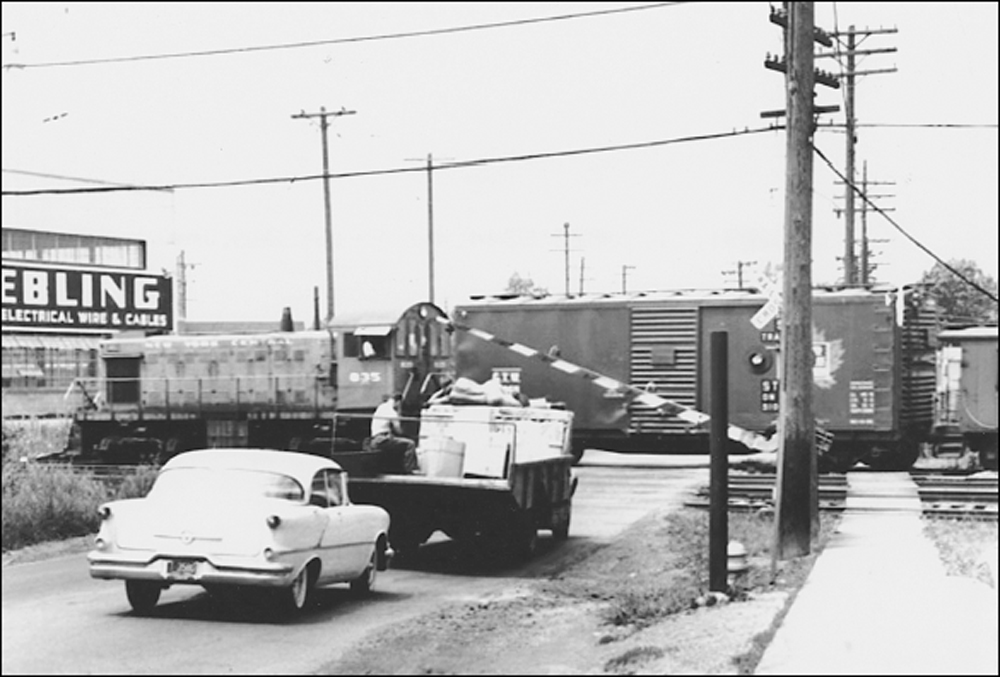

Most people encountered railroads in one or two situations. They rode trains as passengers for business or pleasure, or they found themselves waiting for trains at grade crossings. This 1956 image shows a NYC local freight train crossing Lakewood Heights Boulevard. At the head of the train is Alco S-1 switcher No. 835, which originally wore No. 716 and was eventually assigned No. 9319. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

A collection of NYC motive power spends its final days on the dead line at Collinwood Yard on September 9, 1967, including a locomotive that was involved in a derailment. The XH5 is a steam-heater car that was used on passenger trains to provide steam for heating and cooling. Also shown are No. 8693, a model NW2 switcher; and No. 1736, an F7A road diesel. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

The NYC had 238 F7A locomotives that were built by EMD between 1949 and 1953 and rated at 1,500 horsepower. Although promoted by EMD as a freight-service locomotive, F units were used by some railroads in passenger service. In freight service, they were often used on trains that did not require much switching. Nos. 1675 and 1702 are shown leading a freight at Painesville. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

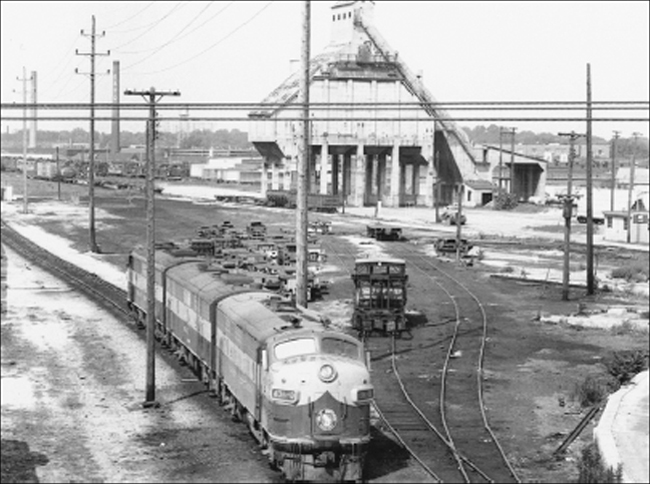

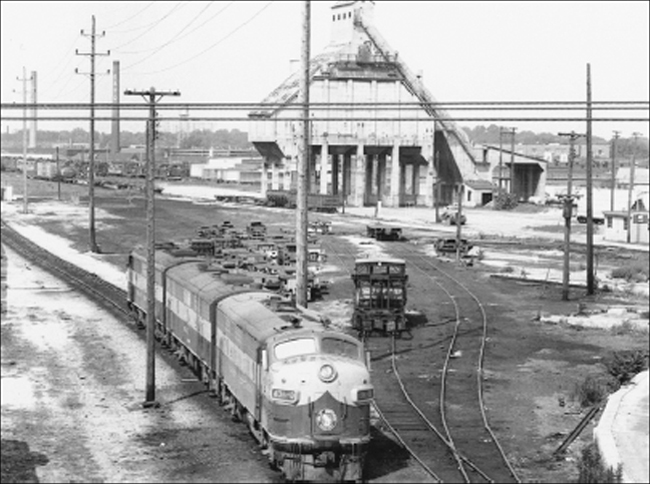

Freight traffic could be seasonal, and a railroad might find itself short of enough locomotive power to handle traffic surges. In such instances, a railroad might lease locomotives from another railroad for the short term. Shown at Collinwood Yard is an A-B-A set of F7 locomotives that the NYC leased from the Great Northern Railway. Behind the locomotives is Collinwood’s massive coal dock. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

The NYC and PRR merged on February 1, 1968, to form Penn Central Transportation Company. For a while, it was common to see locomotives still bearing NYC or PRR markings mixed in with locomotives in PC’s livery of an interlocked P and C. Shown in the foreground of an image made at Collinwood is a lash-up of locomotives with markings from all three railroads. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

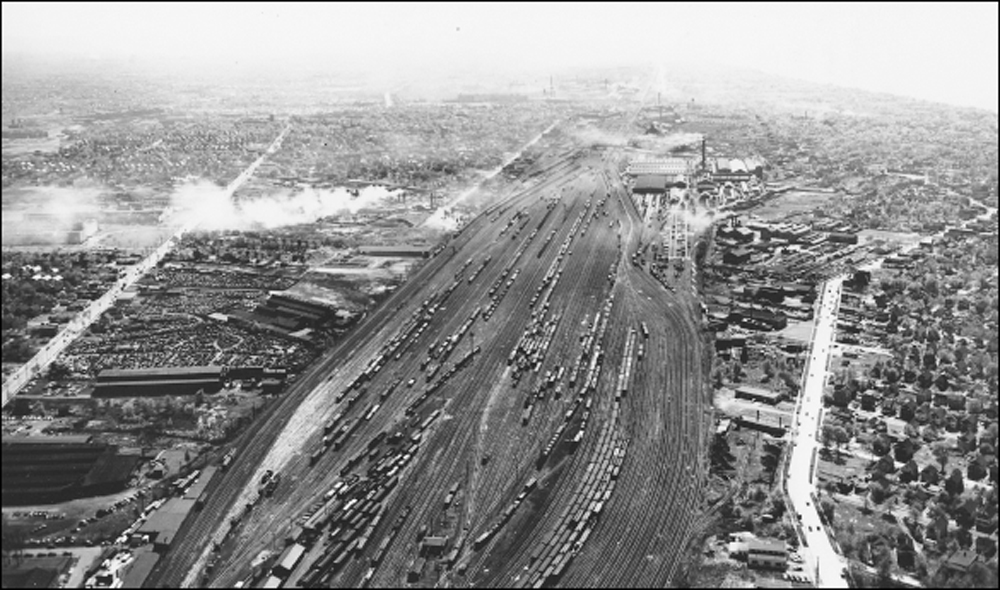

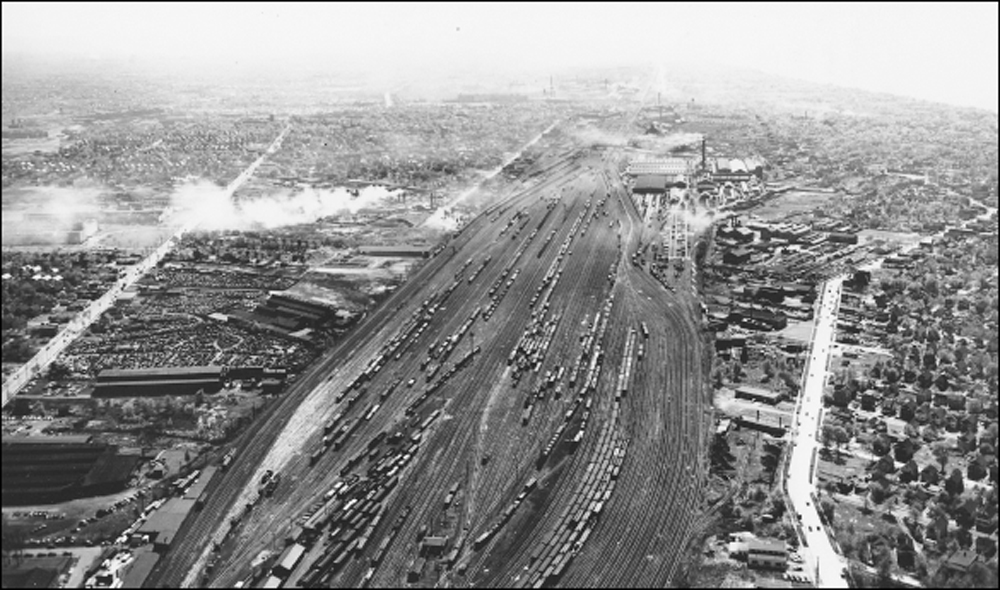

The LS&MS established a yard and repair shops in 1874 in the village of Collinwood, northeast of Cleveland. At that time, the facility had 500 employees who handled 72 freight trains a day. The facility was expanded in 1903 and again in 1929. By now, Collinwood had become a major classification yard for the NYC that employed more than 3,000 and featured 120 miles of track. The village of Collinwood, which had grown to a population of 3,200 by the 1890s, was annexed by the city of Cleveland in 1910. The yard is located between Interstate 90 and Saranac Road. The photograph above, taken on May 4, 1949, provides a sense of how large the yard is. In the photograph below, diesel switchers and one steam locomotive shuffle freight cars and assemble trains. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

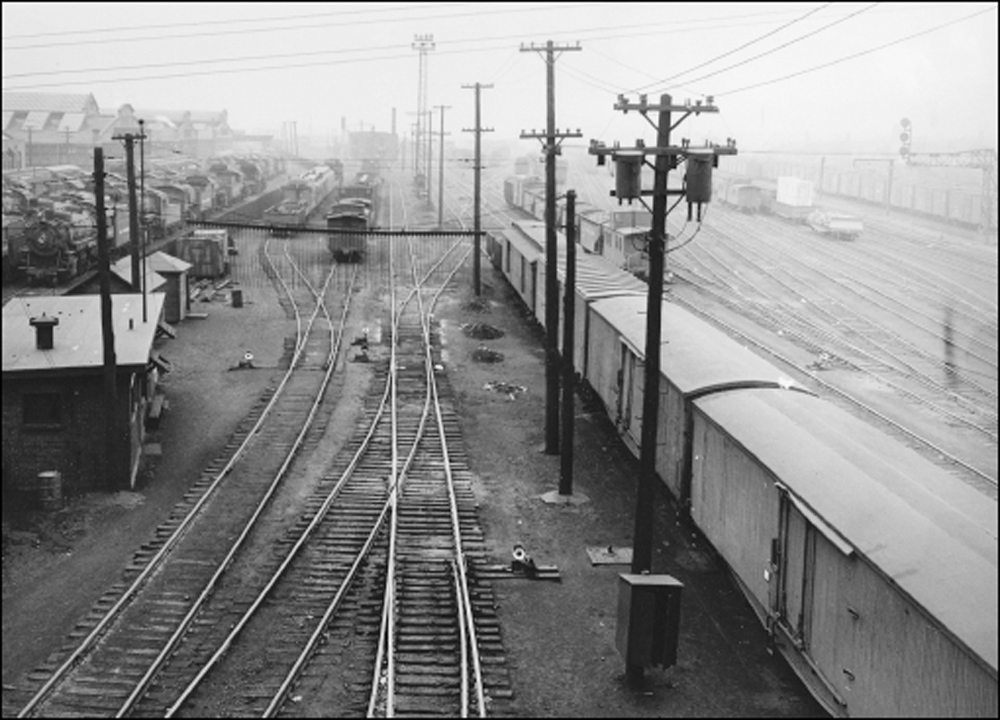

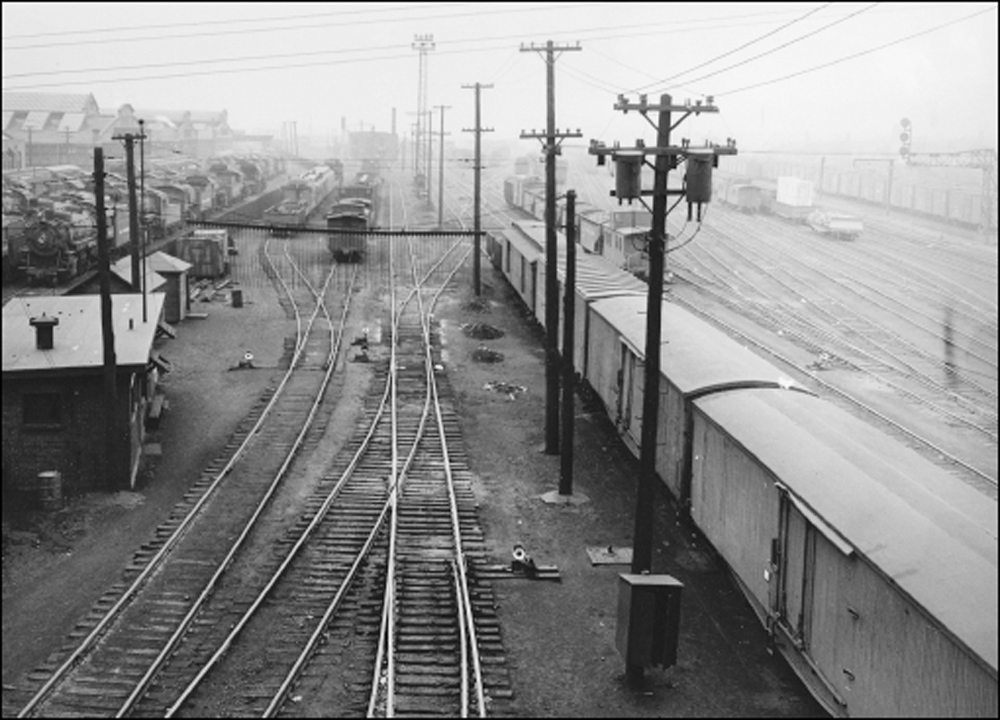

The two images of Collinwood Yard on this page were taken from approximately the same location and show how much a railroad can change in two years. Each photograph was taken on a bridge carrying East 152nd Street over the yard. The image above dates to 1953. Note that there are several steam locomotives clustered near the shop buildings. It is not clear from the information with the photograph if these locomotives were still active or were waiting to be scrapped. The NYC was well along with retiring steam locomotive power used east of Cleveland at this time. The photograph below was taken in March 1955. Steam power had not yet vanished from the NYC, but it had less than two years before it ended. By now, most motive power was diesel locomotives. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

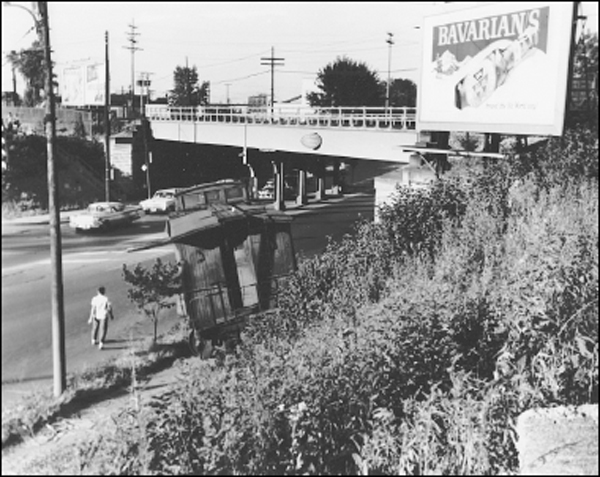

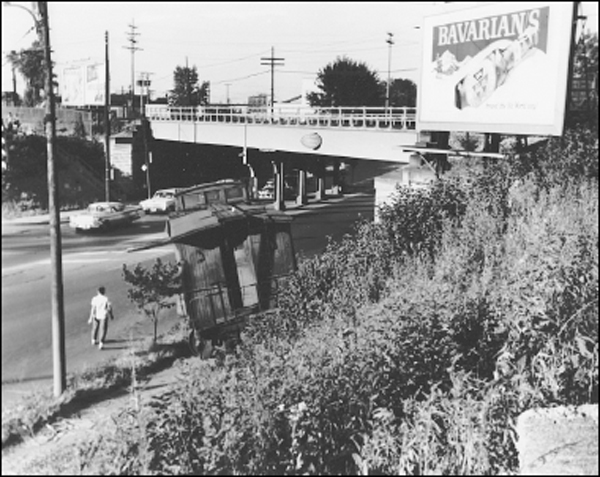

Railroads go to great lengths to avoid accidents that cause injury to employees and the public. In the photograph above, No. 1609 has derailed at Collinwood Yard on May 12, 1950. It took some work to clean this up, but it is not likely that a wrecker will need to be called to the scene. No. 1603 is an FTA model built by EMD. In the photograph below, it took a crane to get this NYC caboose back onto the tracks. This accident occurred along Lorain Street on July 4, 1963. The photograph did not include any information about the cause of this accident, but it does not appear that anyone on the street or sidewalk was injured. The sight of a caboose resting on the sidewalk next to a main street must have attracted a lot of curiosity seekers. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

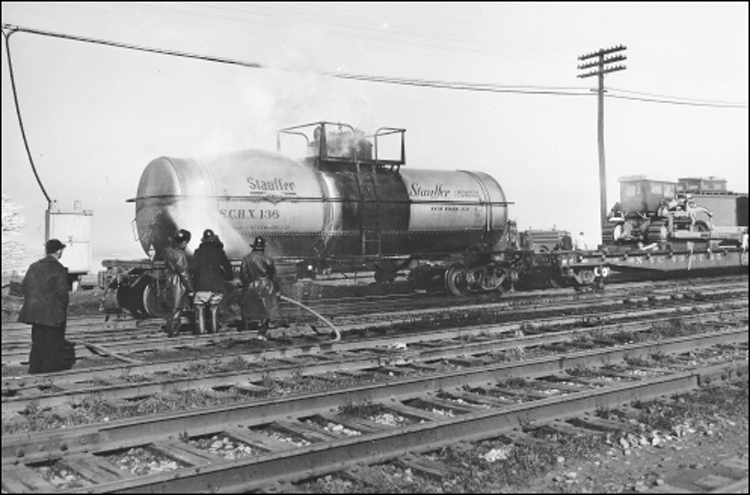

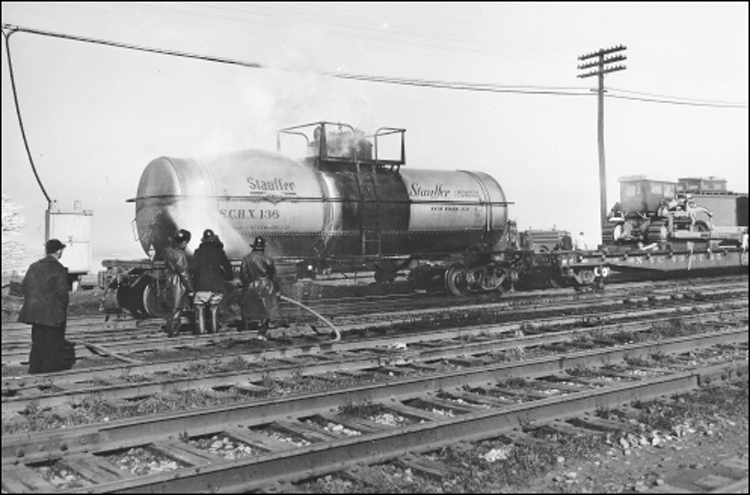

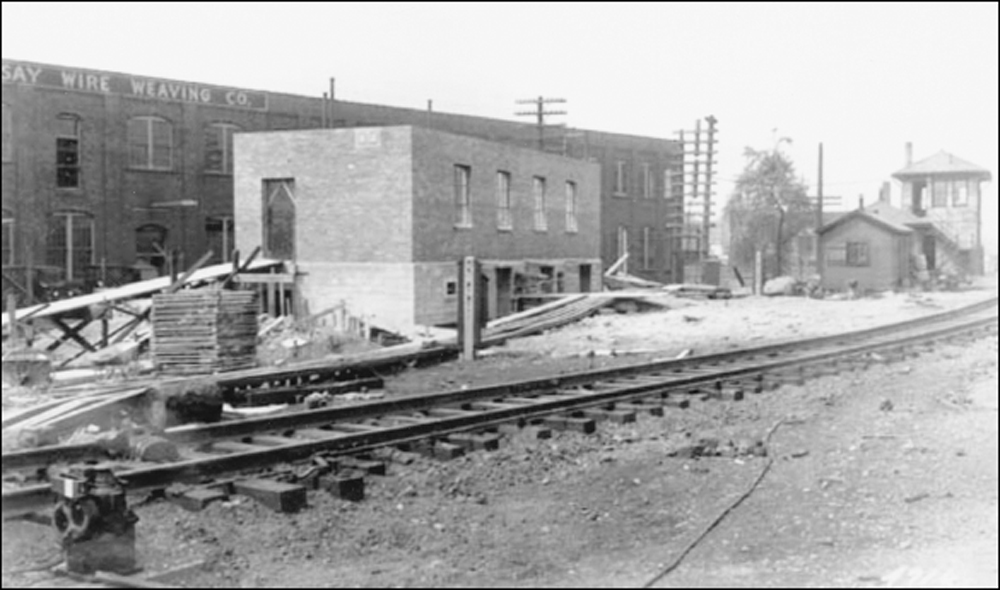

Young businessman John D. Rockefeller shipped oil by rail to Cleveland. By the 1870s, he controlled most of the city’s refineries and had established the Standard Oil Company. Refiners needed sulfuric acid, which prompted the growth of a sizable chemical industry in Cleveland. The city’s chemical factories were soon producing a range of industrial chemicals. The availability of petroleum products in Cleveland also resulted in the development of a paint-and-varnish industry in the 1870s. Henry Sherwin and Edward Williams formed the Sherwin-Williams Company, while Francis H. Glidden in 1875 formed a company that sold varnishes and enamels. It is not clear why firefighters are spraying the tank car shown in these two images. The incident occurred on the NYC on November 9, 1952, near East Twenty-fifth Street and Lakeshore Boulevard. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

This postcard shows an LS&MS locomotive at the Collinwood roundhouse in about 1908. Note that the tender carries the name “New York Central Lines,” a designation that the NYC used on equipment assigned to railroads that it leased. The brick roundhouse was built when Collinwood Yard was established in 1874. It has since been demolished, but locomotive-service facilities still exist at Collinwood, which is now owned by CSX Transportation. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Approximately 60 years after the image above was made, the motive power at Collinwood changed dramatically. Steam locomotives were gone, but some shops that were built to care for them still stood. PC No. 2628 (left) is a U25B originally built in 1962 for the PRR for heavy freight service. NYC No. 4023 is an E7A locomotive built for passenger service. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

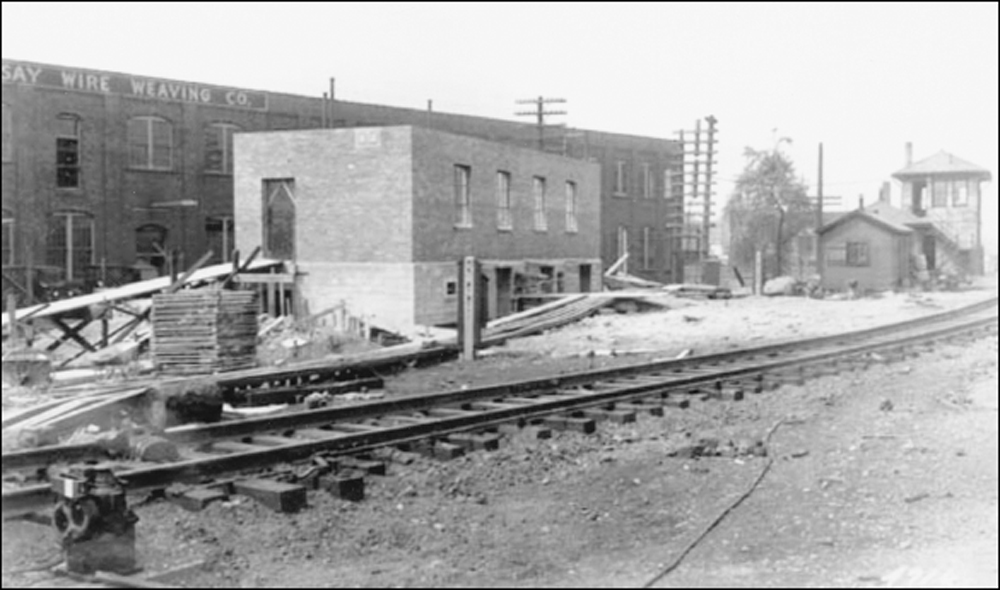

QD Tower, later known as Quaker Tower, controlled the interlocking plant at Collinwood where tracks of the NYC’s Short Line and Lakefront Line and the CUT came together at the west end of the yard. The tower is shown under construction in an undated photograph. It continued in service through the 1990s, but control of the interlocking was later passed on to a dispatcher, and the tower was closed. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

A wide variety of diesel locomotive power passed through the Collinwood locomotive service facilities during the late 1960s, particularly after the PC merger. Shown in the fall of 1968 are an Alco locomotive that was painted into the Spartan PC livery and some NYC power that still has its original markings. First- and second-generation diesels were common at Collinwood in this era. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

The LS-1000 was introduced in 1949 by Lima Locomotive Works. Only 38 units were built, including six for the NYC. No. 8407 originally was lettered for a NYC subsidiary, the Chicago River & Indiana Railroad, but by the time this photograph was made, it had been reassigned to the NYC roster. It is shown working in a Cleveland scrap yard on June 29, 1968. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

Here, PC is 11 months old, and the Collinwood locomotive-service facility remains the place to photograph a variety of motive power. In this image made on November 16, 1968, passenger and freight power alike await their next assignments. PC aggressively sought to end the remaining passenger service on the former NYC and PRR, so the need for E7A No. 4019 was diminishing. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

GP7 No. 5761 leads a parade of EMD and Alco power east of Cleveland. F units were used by the NYC and PC to pull freight trains in the Cleveland area. One F7A locomotive, No. 1648, was painted in Consolidated Railroad Corporation colors and was still working in the mid-1970s. No. 5751 also joined the Conrail roster when that railroad was created on April 1, 1976. (Photograph by Robert Farkas)

The NYC and Nickel Plate Road shared this station in East Cleveland, shown in January 1962, which was located along the electrified portion of the CUT tracks. The NYC had a 91.5-percent ownership share, while the NKP owned 8.5 percent. The NYC was responsible for station operations and maintenance, but each railroad owned and maintained its own platforms, canopies, and elevators. (Photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

When the LS&MS built this station in Olmsted Falls in 1876, it was way out in the country. NYC passenger trains still stopped here twice a day through late 1949, but by late 1952, no trains were scheduled to stop in Olmsted Falls. Located 15 miles west of CUT, the Olmsted Falls depot is today owned by the Cuyahoga Valley & West Shore Model Railroad Club. (Photograph by Craig Sanders.)

The Cleveland Group Plan designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham called for a Union station along the lakefront, but Cleveland businessmen and brothers O.J. and M.P. Van Sweringen led a campaign that, in January 1919, culminated in the passage of an ordinance to locate the station on Public Square. The west approach tracks are shown here under construction, and the B&O station is visible to the left. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

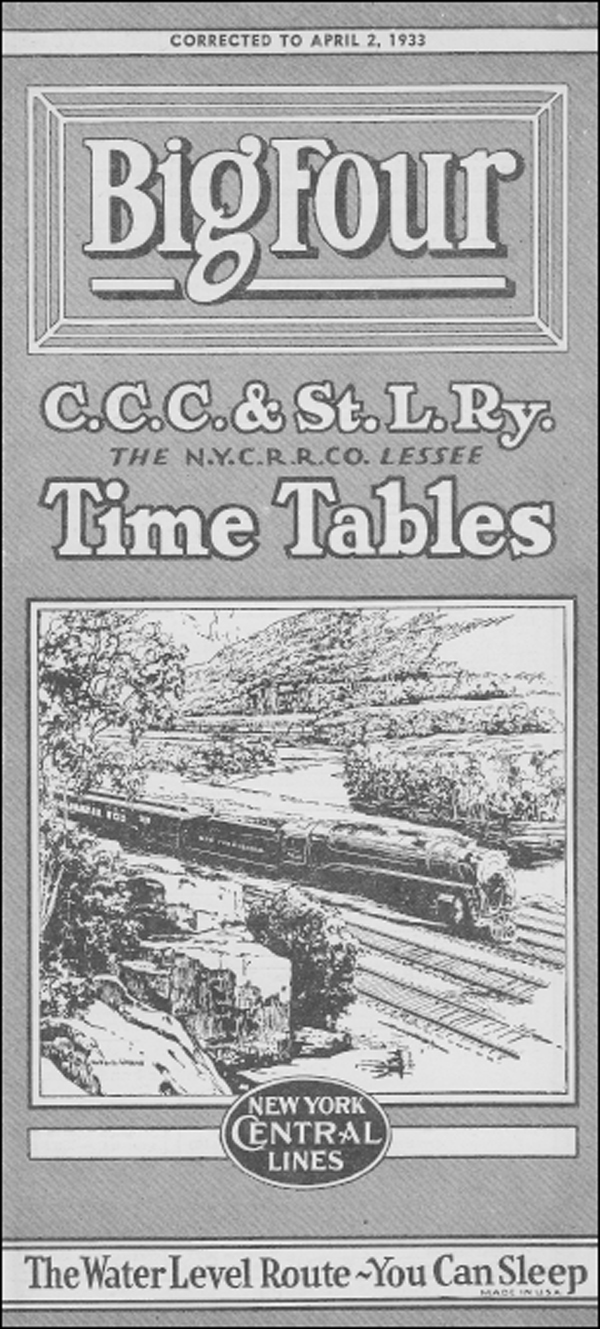

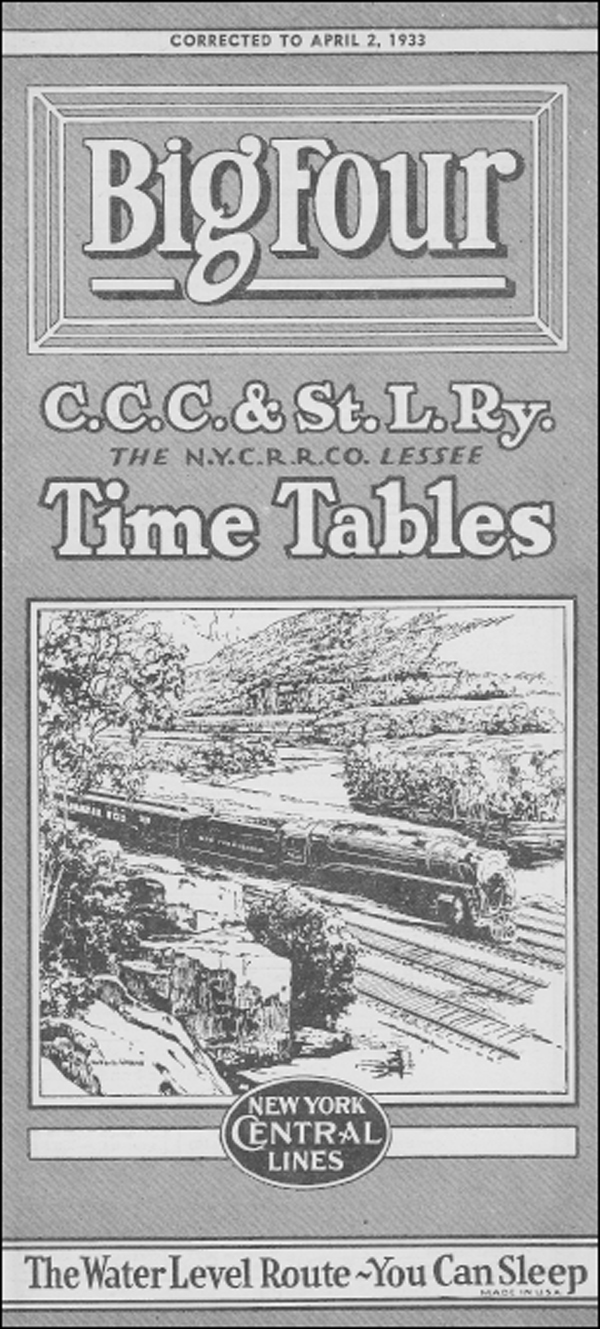

Railroads used timetable covers as a marketing tool. The image at left shows a timetable issued on April 2, 1933, by the Big Four, which at the time was still an autonomous entity even if it was controlled by the NYC. The somewhat ornate design clearly reflects the NYC control of the Big Four. The slogan, “The Water Level Route— You Can Sleep,” was used by the NYC for decades. The image below shows a regional timetable issued by the NYC on November 5, 1967. By now, NYC timetable covers were more functional, showing only the scope of service, and NYC passenger service in Cleveland had shrunk to nine trains a day. These trains continued to operate during the PC era, and all were discontinued on May 1, 1971, with the coming of Amtrak. (Both, Craig Sanders collection.)

The Van Sweringens envisioned that CUT would serve all steam railroads, most interurban railways, and their planned regional rapid-transit system. But interurban railways were declining and never used CUT. The PRR announced in December 1919 that it would not use CUT. Only the Shaker Heights Rapid of the proposed rapid-transit network was ever built. Shown are the tracks at the east end of CUT just before its opening. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The Hudson steam locomotives of the NYC were numbered consecutively, starting with 5200 and ending with 5474. To do this, the NYC renumbered some Hudson locomotives on its B&A subsidiary that had arrived with road numbers 600–619. No. 5266 is a J1-class Hudson built by Alco in 1927. It is shown pulling No. 624, a Cleveland-to-Baltimore train that operated over the Erie and B&O Railroads. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC and PRR were the dominant passenger carriers between Chicago and New York, and no other railroad could match the number of trains that each offered. The NYC and PRR had another edge in that they went into Manhattan. The New York trains of other carriers terminated in New Jersey, and passengers had to take a boat or bus to Manhattan. The PRR’s Chicago mainline passed through Canton, 60 miles south of Cleveland. The NYC offered the most destinations from Cleveland as well. From Cleveland, the NYC had direct service to Florida via an interchange at Cincinnati with the Southern Railway and the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. The photograph above shows eastbound No. 78 in Cleveland on May 1, 1938. The photograph below was also made in Cleveland but is undated. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

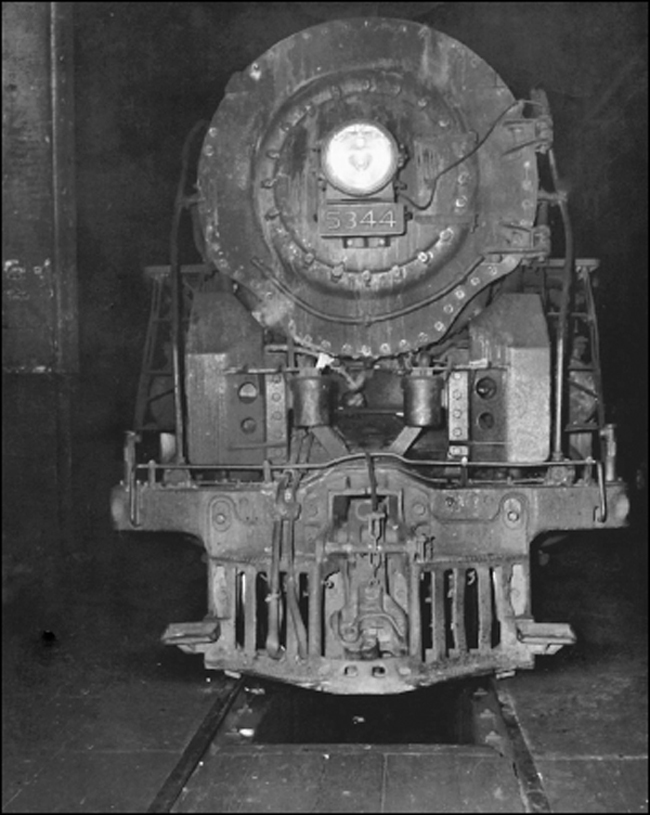

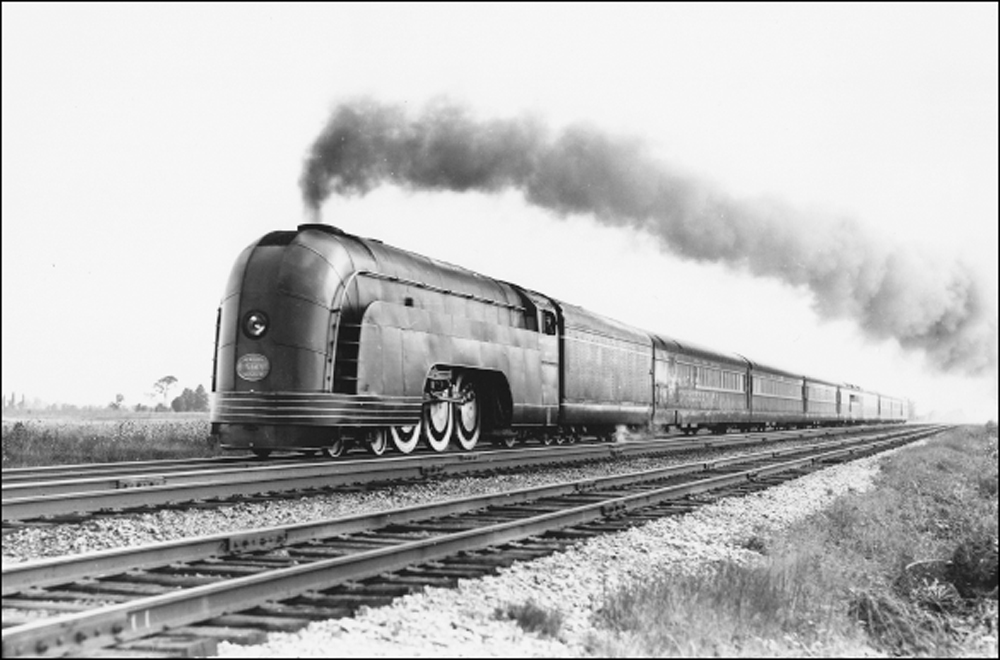

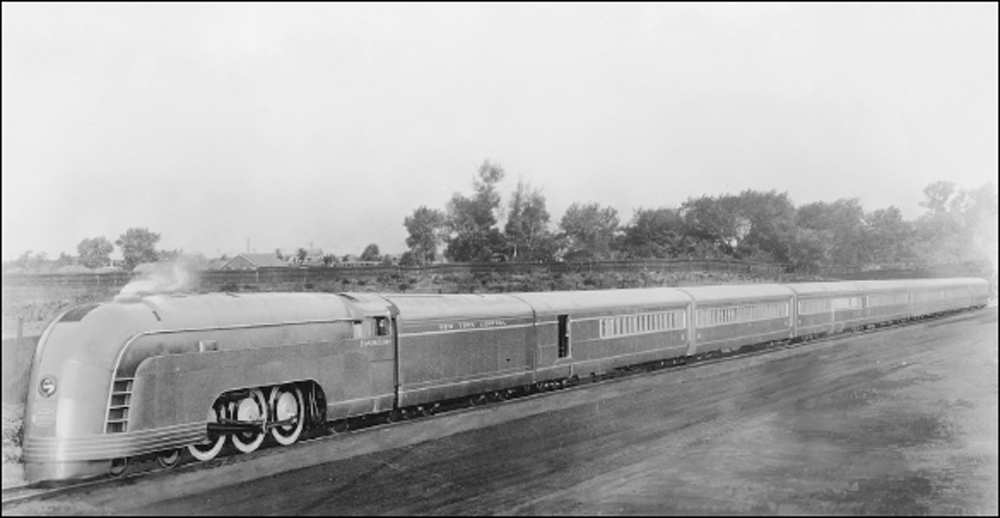

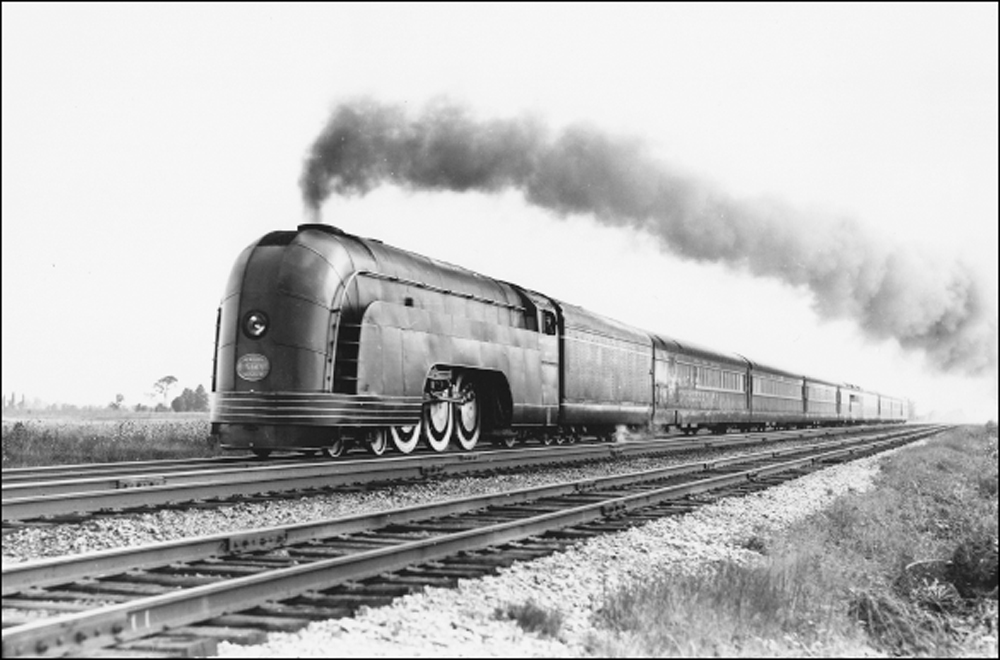

A total of 13 of the NYC’s 4-6-4 Hudson-type steam locomotives were streamlined. No. 5344 was the first to be streamlined, receiving a “bathtub-like” shrouding in 1934 that was designed by the Case School of Science in Cleveland. In 1938, Alco built 10 J-3–class Hudsons—Nos. 5445 through 5454—with a streamlined look created by industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss. The streamlined design was intended to complement the motif that Dreyfuss gave to new passenger cars ordered for the Twentieth Century Limited. In the photograph above, No. 5445 leads No. 49, the Iroquois, through Cleveland on August 10, 1939. This New York–to-Chicago train was renamed the Chicagoan on April 27, 1957, and continued in service until December 3, 1967. In the bottom photograph, No. 5449 leads an unidentified train in Cleveland in 1939. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

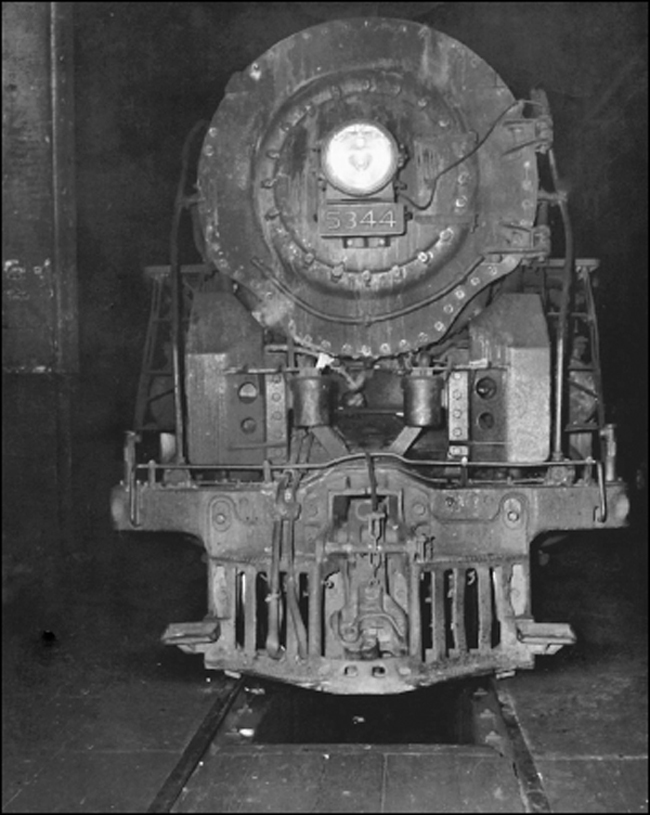

No. 5344 was the NYC’s first steam locomotive to be streamlined. After receiving a “bathtub-like” shroud in 1934, it pulled the Twentieth Century Limited between Chicago and Toledo. It received new shrouding in July 1939 to match the look of newly built, streamlined J3s. The shrouding was removed following a grade-crossing accident with a sand truck. No. 5344 also served as the prototype for a Lionel O-gauge model. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

In June 1938, the NYC debuted a new look for its flagship Twentieth Century Limited. The cars received a livery of two-tone gray with blue and silver stripes. This train, photographed in Cleveland on May 8, 1940, reflects that new look, but the Century came through during nighttime hours. It is either a very late Century, the Commodore Vanderbilt, or the Southwestern Limited, which also received cars with the new livery. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC developed the Hudson-type steam locomotive in 1926 because it needed a more powerful engine for passenger service. The existing Pacific-type locomotives could only handle 12 cars, and some mainline trains had to operate in separate sections. The NYC and its subsidiaries eventually operated 275 Hudsons. No. 5248 has a seven-car train in tow in the late 1930s in Cleveland. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

NYC locomotive No. 3315 has an 11-car train in hand under the CUT wires on July 24, 1934. The train’s makeup, with its heavyweight cars, is typical of the era. Supplementing the three head-end cars is a combine. During the 1930s, many railroads stepped up their efforts to air-condition their passenger cars, and they prominently promoted this in timetables and advertisements. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The Forest City operated on an overnight schedule between Cleveland and Chicago. It carried numerous sleeping cars and coaches. During the World War II era, it operated in two sections eastbound, with the Advance Forest City continuing to New York. The two sections were scheduled to depart Chicago 10 minutes apart, but they arrived in Cleveland 50 minutes apart. The eastbound Forest City is shown at Cleveland on May 1, 1938. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The Niagara-type locomotive was a 4-8-4 built by Alco. On other railroads, this type of locomotive was known as a Northern, but NYC named its fleet after Niagara Falls. NYC ordered 27 of these locomotives, and they were delivered between 1945 and 1946. Following World War II, they were used primarily in passenger service. No. 6021 is shown pulling the New York Special at Berea in an undated photograph. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Hudson-type locomotive No. 5312 pulls an unidentified passenger train in June 1955 at Linndale during the twilight era for steam power on the NYC. The last steam operation on the NYC occurred on May 2, 1957, when class H-7a No. 1977 (a 2-8-2), formerly No. 6177, worked for the last time at Riverside Yard in Cincinnati. By mid-August 1953, NYC steam locomotives no longer operated east of Cleveland. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

In the mid-1930s, the NYC operated nine round-trips between Cleveland and Cincinnati via the former Big Four. Many of those trains featured the names of the endpoint cities in their names, including No. 119, the Cincinnati Special, which is shown in Cleveland on May 6, 1939, behind Big Four No. 4926, a 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotive. No. 119 made the trip to Cincinnati in six hours flat. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC and PRR also fiercely competed in the New York–St. Louis market, but the PRR had the faster, more direct route. In Cleveland, the NYC had the only direct service to St. Louis. Cleveland–St. Louis service crested in 1930 at seven round-trips. The premier train was the Southwestern Limited, which the Big Four had begun on October 6, 1889. Other notable St. Louis route trains included the Knickerbocker and the Missourian. NYC sought to end all passenger service west of Indianapolis, but state regulatory commissions in Indiana and Illinois only allowed the discontinuance of two of the four pairs of trains that operated to St. Louis, effective August 17, 1958. The Southwestern Limited is shown above westbound in Cleveland on May 1, 1938, while an unidentified westbound train is shown below on the ex–Big Four at Wellington in 1954. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

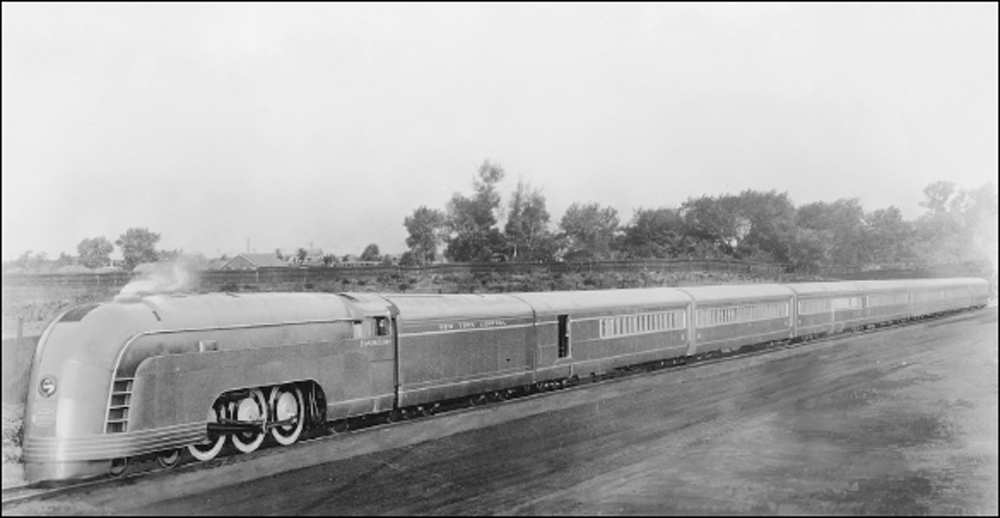

The Mercury was a streamlined passenger train that began Cleveland-Detroit service on July 15, 1936. The NYC could not afford new equipment, so it rebuilt Osgood-Bradley commuter coaches into luxury coaches, a lounge car, a diner, and an observation car, all designed by Henry Dreyfuss. The Mercury made the trip to Detroit in slightly less than three hours, with Toledo being the only intermediate stop. The equipment featured a striking design. Inside were curved leather divans and armchairs rather than the traditional two-by-two seating. The 4-6-2 Pacific locomotive was shrouded except for its driving wheels, which were illuminated at night. By its first anniversary, the Mercury had grown from seven to nine cars and had carried 112,000 passengers. The NYC subsequently launched a series of Midwest-corridor trains with the Mercury name, including one operating between Cleveland and Cincinnati. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

For more than two decades, NYC passenger trains serving CUT operated with P1a electric locomotives. CUT ordered 22 of the 3,000-volt locomotives from Alco-General Electric, and they were built between 1929 and 1930. NYC trains switched from steam to electric power at Collinwood Yard on the city’s east side and at Linndale on the west side. NYC constructed a repair shop at Collinwood that was still called “the P1a” decades after the electrics had been removed from CUT service. In the photograph above, NYC No. 407, the westbound Cleveland–St. Louis Special, has exchanged its P1a in September 1953 for a steam locomotive at Linndale, which was located on the former Big Four. In the photograph below, P1a No. 206 has hooked onto an eastbound train in September 1952 and is heading toward CUT. (Both photographs by Herbert Harwood.)

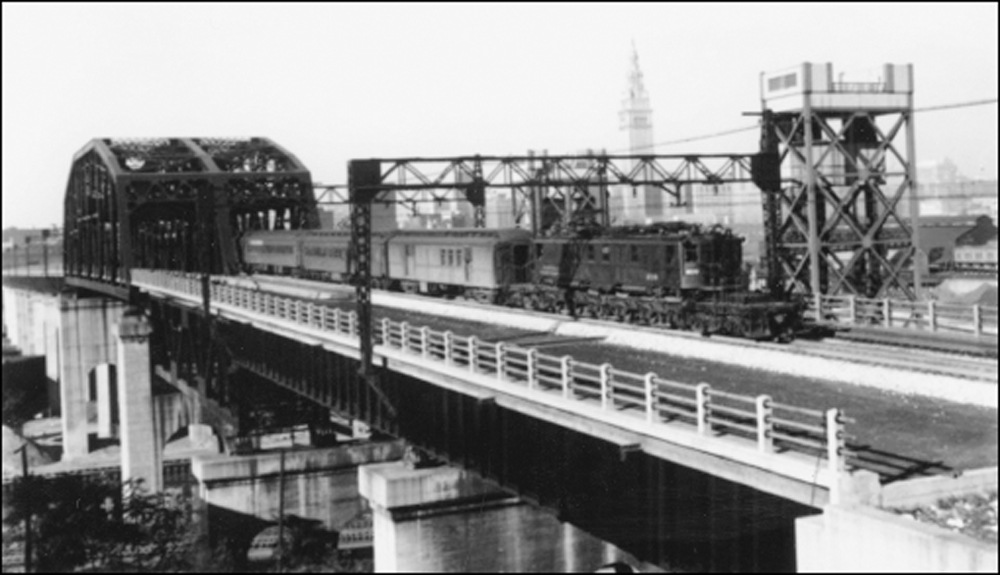

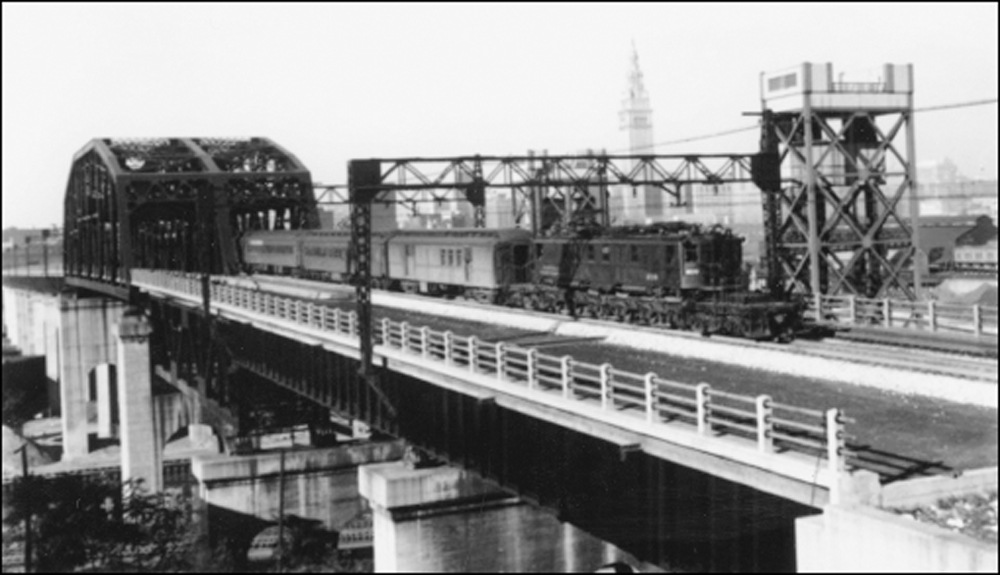

CUT built 17 route miles of electrified track to avoid smoke and soot coming from its underground station. CUT’s P1a electric locomotives were 80 feet long and weighed 204 tons. By the early 1950s, most of the passenger trains using CUT used diesel-electric locomotives, and the need for electric locomotives diminished. CUT ceased using its P1a locomotives in 1953, and 21 of them were refurbished by the NYC for use in the electrified territory of New York City, where they operated as P2 locomotives. In the photograph above, an NYC train has departed CUT and is approaching West Twenty-fifth Street in 1944. This bridge over the Cuyahoga River was built as part of the CUT project. In the photograph below, a P1a pulls the Empire State Express through East Cleveland in 1954. (Above, photograph by Anthony Krisak; below, photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

Steam locomotives briefly operated out of CUT in the 1950s. Here, NYC No. 3012 has train No. 433, the Cleveland-Cincinnati Special, charging over the CUT viaduct in January 1955. No. 433 carried a sleeper as a parlor car and a diner/lounge. It made the trip to the Queen City in six and a half hours. The last steam operations on the NYC occurred on the former Big Four routes. (Photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

CUT had three SW900 switchers and four GP9 diesels that were purchased by the NYC but lettered for and assigned to duty at CUT. Switchers were needed to switch passenger cars, and mail and express cars from many of the trains that called at CUT. No. 8629 eventually passed to Conrail ownership before being sold to a New Jersey steel company. (Photograph by Robert Farkas.)

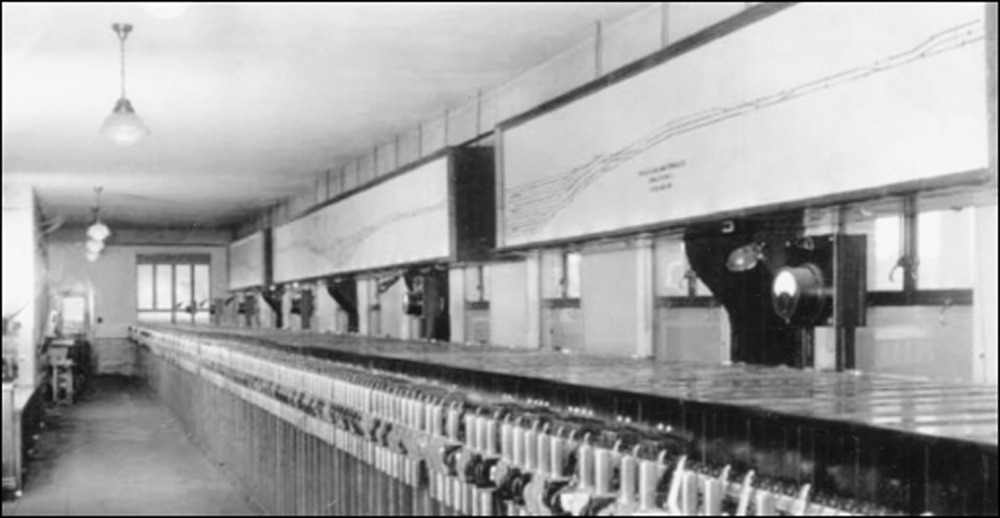

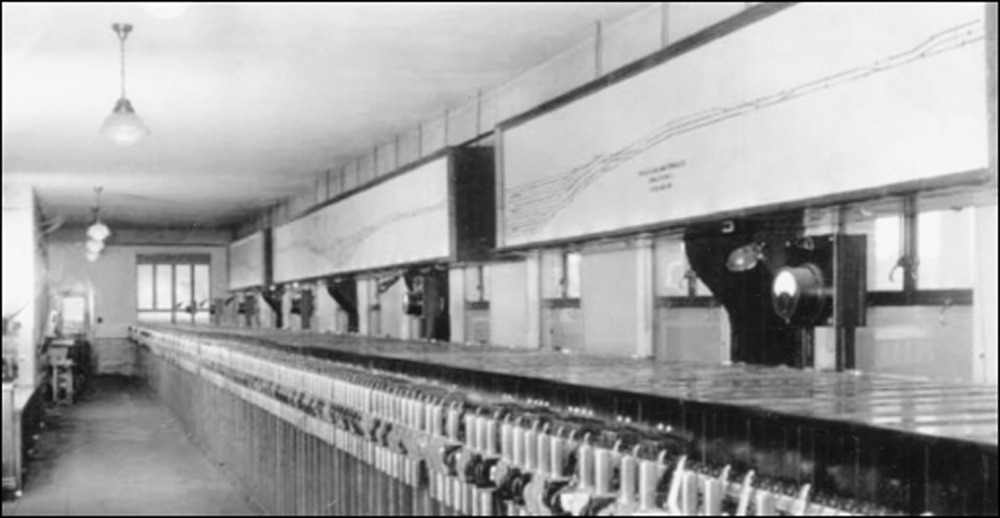

CT Tower controlled train movements over three and a half miles of CUT track between East Thirty-fourth and West Twenty-fifth Streets. Operators used levers to set the signals and switches. The CT interlocking machine had 576 levers and was the largest electromechanical interlocking machine in the country when CUT opened in 1929. The model board above the interlocking machine showed the locations of trains, and lights illuminated when trains passed certain control points. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Although four railroads used CUT, only the passenger trains of the NYC and NKP used the CUT viaduct over the Cleveland Flats west of the station. NYC No. 407, the Cleveland-St. Louis Special, departs CUT in December 1954 shortly past noon en route to St. Louis. This train carried coaches and a parlor car out of Cleveland and picked up a dining car in Indianapolis. (Photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

The South Shore operated between New York and Chicago. A late 1959 timetable showed that it was scheduled to arrive into Cleveland at 5:55 p.m. and operated as a local across Ohio. Shown at old Broadway Avenue in Cleveland in April 1960, No. 43 picked up coaches at Cleveland for Chicago but carried no sleepers west of Buffalo. It was discontinued on September 24, 1960. (Photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

The October 24, 1959, NYC timetable listed 29 passenger trains through Cleveland, including four that did not serve CUT. Most trains operated on the Water Level Route between Chicago and New York, including seven that originated or terminated in Cleveland. One pair operated between Cleveland and St. Louis, two between Cleveland and Indianapolis, and three between Cleveland and Cincinnati. Shown is No. 234 in June 1960. (Photograph by Herbert Harwood.)

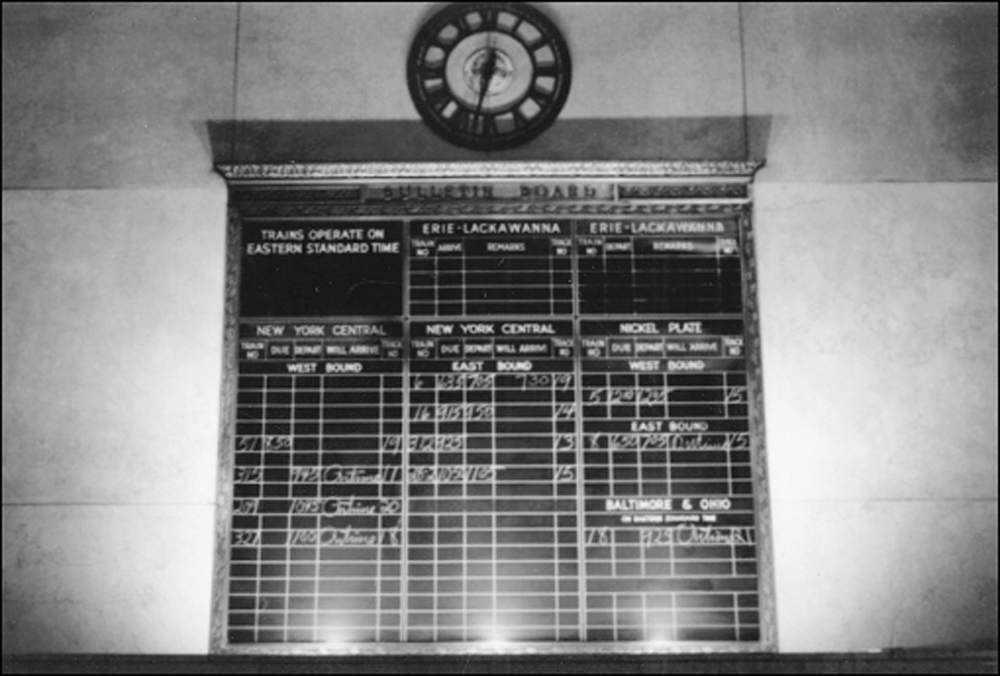

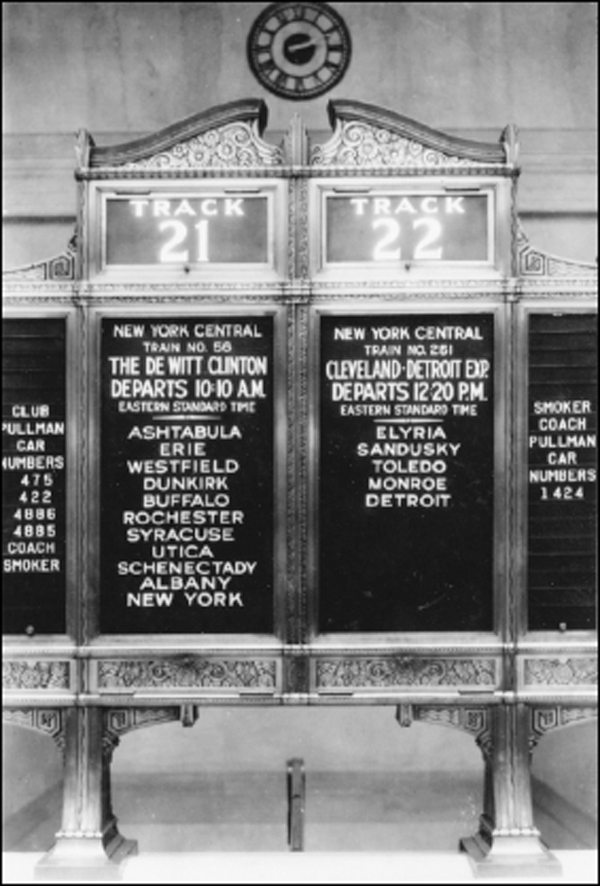

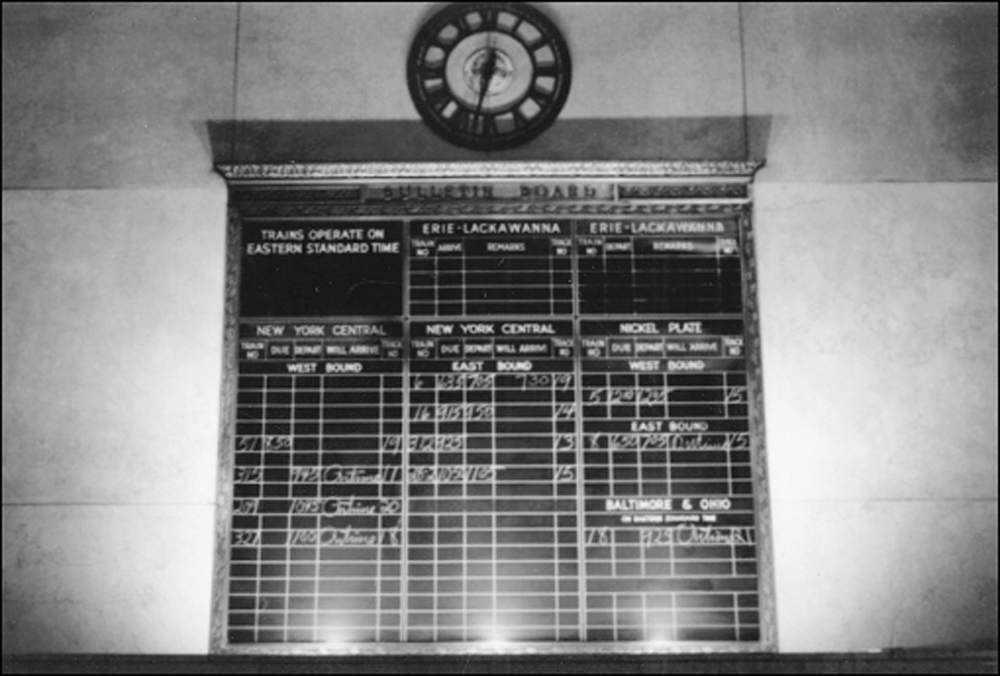

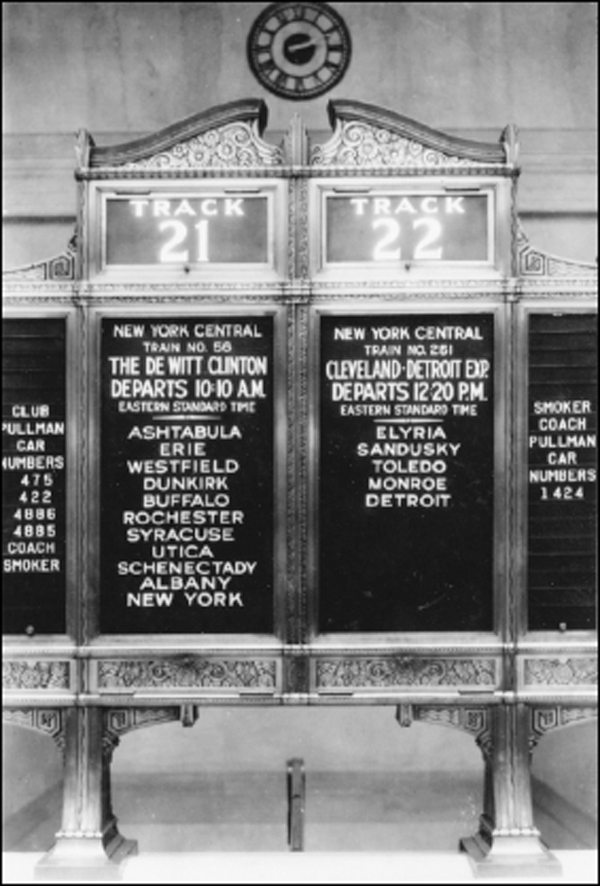

Travelers and visitors could check the status of trains on the CUT bulletin board where station personnel wrote in chalk the latest information. The above photograph taken in February 1962 at 6:30 p.m. shows trains scheduled for that evening. Passengers boarded from a concourse area that had stairways leading down to the platforms below. For each doorway, there was an ornate train-information stand that showed the train number, name, and select cities served by that train. Also shown was the location of the cars in the train. Therefore, a passenger holding space in sleeper No. 4885 could tell at a glance where that car was in the makeup of NYC train No. 56. When a train was ready for boarding, a gateman opened the doors to the stairway. (Above, photograph by Herbert Harwood; left, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC’s oval-shaped logo dated to 1893, although its interior design was tweaked over the years. In 1959, the NYC adopted a new logo, which became known as the “cigar band logo.” Freight and passenger locomotives were repainted between 1960 and 1962 into a minimalist black livery, with freight locomotives featuring a white stripe on their lower flanks. Shown is GP9 No. 7392 working during the mid-1960s. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The Ohio State Limited, shown on June 3, 1967, was the NYC’s premier passenger train between New York and Cincinnati. It featured sleepers, coaches, a diner, and, until October 1956, a lounge-observation car. Nos. 15 and 16 were discontinued between Cleveland and Buffalo on November 5, 1967. The Cleveland-Cincinnati segment continued as an all-coach train until the Columbus-Cincinnati leg was discontinued in 1969, ending direct Cleveland-Cincinnati rail passenger service. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The NYC named its Budd Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) “Beeliners.” In the early 1960s, a daytime train named the Miami Valley Beeliner operated from Cleveland to Cincinnati. There was no corresponding return train, so the RDC equipment returned empty or was attached to another train, probably the Night Special. RDCs returned to the Cleveland-Cincinnati route in late 1967 upon the discontinuance of the Ohio State Limited east of Cleveland. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

As passenger patronage fell in the 1960s, the NYC reduced passenger train consists to a bare-bones operation. Shown is a typical consist of the mid-1960s—a GP7 locomotive, a railway post office, and two coaches. NYC ended its last direct service between Cleveland and St. Louis on September 6, 1967, by ending the westbound Knickerbocker and eastbound Southwestern between Cleveland and Union City, Indiana. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)