Five

PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) had just one route to Cleveland, but it was a busy one, hosting a steady procession of freight trains that served the region’s steel and automotive industries. The PRR line had an active passenger operation until the 1960s.

The route began with the March 14, 1836, chartering of the Cleveland, Warren & Pittsburgh Railroad (CW&P), which intended to build from Cleveland to the Ohio River and connect with a railroad expected to be built from Pittsburgh. An economic downturn stalled development of the CW&P for nine years. Renamed the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad (C&P), the company was reorganized by the Ohio legislature on March 11, 1845. The reorganization also changed the route from “the most direct in the direction of Pittsburgh” to “the most direct, practicable, and the least expensive route to the Ohio River, at the most suitable point.” That point turned out to be Wellsville, Ohio.

In July 1847, contracts were awarded for constructing the railroad from Wellsville northward. Construction from Cleveland lagged until the C&P received an infusion of cash from the city of Cleveland. On April 18, 1853, the Pennsylvania Legislature approved an act incorporating the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad Company and gave it authority to comply with all provisions of the C&P’s Ohio charter.

The C&P was built to haul coal from eastern Ohio mines to Cleveland. But on June 24, 1856, the first boat carrying iron ore from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula arrived in Cleveland, and the C&P was soon feeding iron ore to the growing steel industry of Northeast Ohio and Western Pennsylvania.

The C&P’s freight business caught the interest of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago Railroad (PFtW&C), which leased the C&P in 1862. The C&P crossed the PFtW&C at Alliance. Seven years later, the PRR leased the PFtW&C, forming the PRR’s western extension from Pittsburgh to Chicago. The PRR then leased the C&P on December 1, 1871, for a period of 999 years.

Today, the former C&P is owned by Norfolk Southern Railway and is a key component of its route between Chicago and the Mid-Atlantic region.

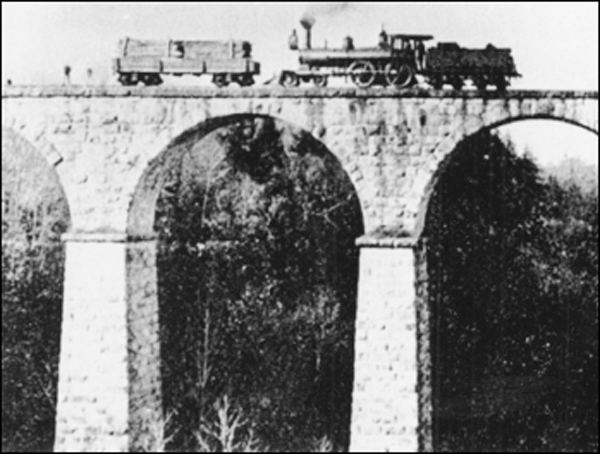

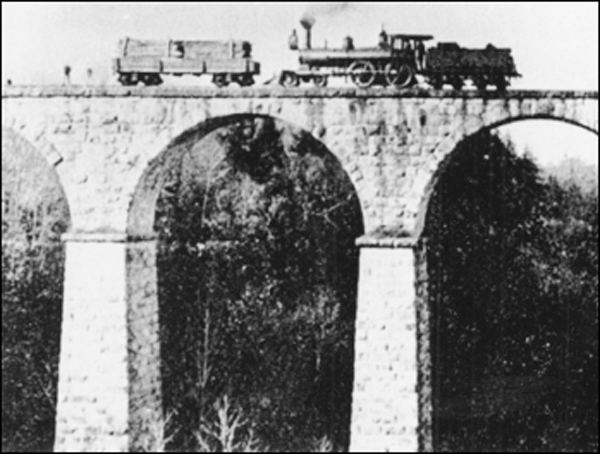

The C&P crossed Tinker’s Creek in Bedford on a wood trestle. In 1864, the railroad built the stonemasonry arch bridge shown in this 1880 image. It was 100 feet tall and 200 feet long, and its arches were spaced 50 feet apart. The bridge was abandoned during a 1901 line relocation project, and fill was placed around it. The top of the bridge exists today in Viaduct Park. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

A PRR passenger train has stopped at the pier at the foot of Columbus Avenue that served Cedar Point boats. This may be a special train because it carries a banner reading, “Kilbourne & Jacobs Mfg. Co., Columbus, Ohio” on the side of a passenger car. Steamships shown are the A. Wehrle, Jr. (left) and the Arrow. Slightly visible behind the pier is the R.B. Hayes. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

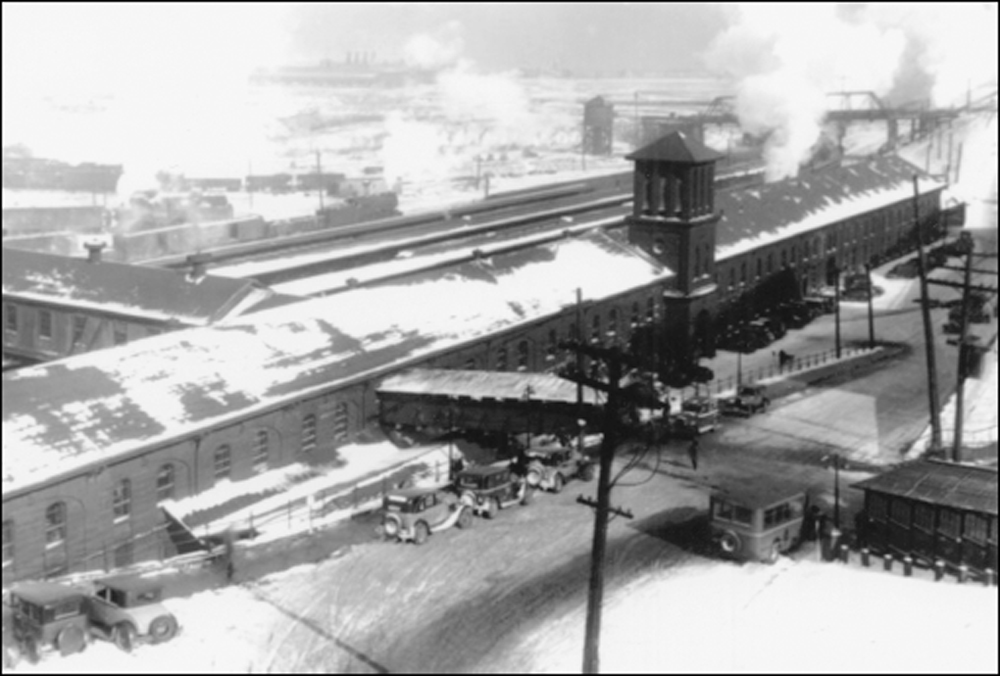

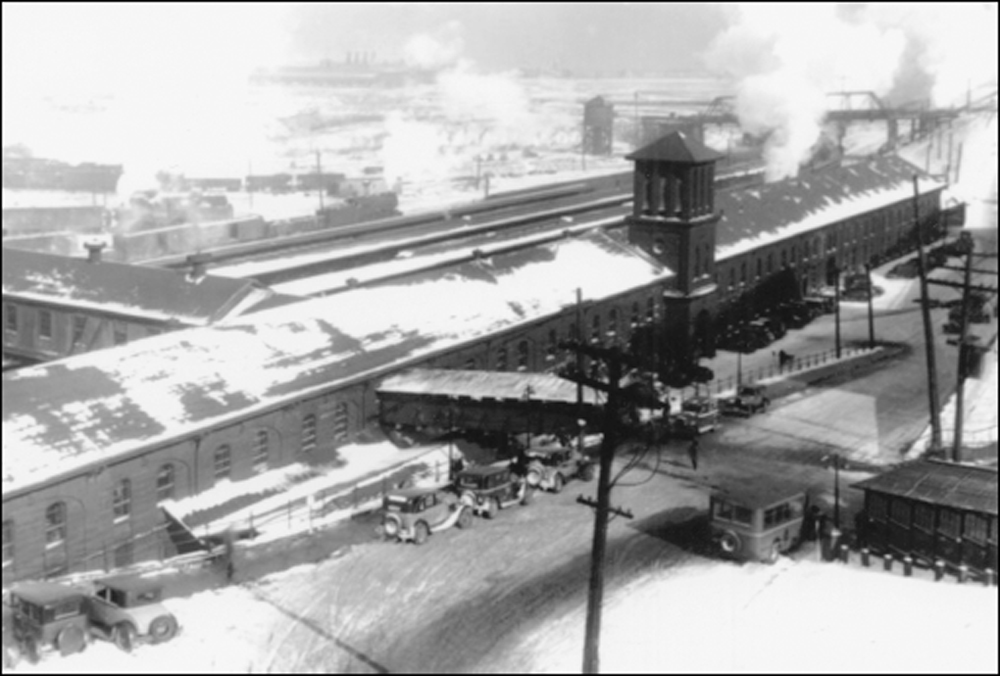

By the 1890s, Cleveland Union Depot had become a civic embarrassment. It was too small for the level of passenger traffic it served, and it appeared dingy and grimy. Someone placed a sign nearby imploring travelers not to judge Cleveland by its train station. Plans to replace it in the early 20th century were thwarted by World War I. All railroads serving the station, except the PRR, agreed to use the new CUT, which opened in 1929. The PRR remained at Union Depot until September 1953, when it began originating and terminating its Cleveland passenger trains at a station at Fifty-fifth Street and Euclid Avenue. Union Depot was demolished in 1959. In the image below, a PRR switcher works at the station in September 1950. A portion of Cleveland Municipal Stadium can be seen at right. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The June 24, 1856, arrival of a Lake Erie freighter hauling iron ore from the upper peninsula of Michigan began the long history of ore hauling by rail from Cleveland. As the steel industry in Ohio and Pennsylvania grew, this business boomed. The C&P purchased land on Whiskey Island near the mouth of the Cuyahoga River for an ore-loading facility. In the early 1900s, the PRR developed a new lakefront unloading facility that featured four Hulett unloaders. The Huletts used clamshell buckets to unload ore from boats. Cars were stored in an adjacent marshalling yard until they were ready for loading beneath one of the Huletts. The photograph above shows tracks leading into a Hulett unloader. The photograph below shows an overhead view of a Hulett unloading an ore boat. The Huletts were removed from service in 1992 and dismantled. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

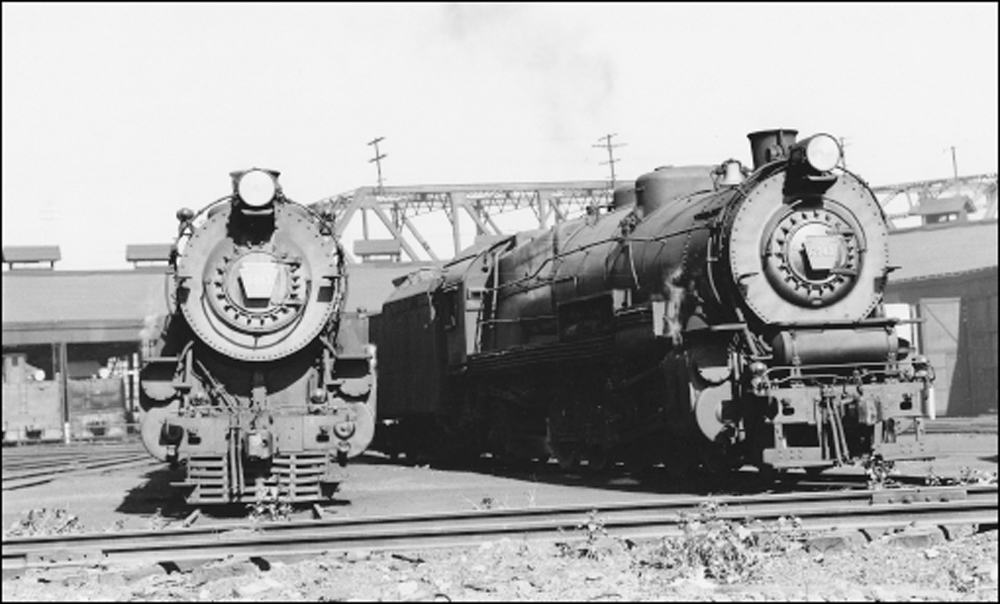

The PRR had one of the largest steam locomotive fleets in the country, and during the late steam era, it had more locomotives of certain types than some railroads had in their entire steam fleet. The PRR tended to develop specifications for locomotives and take those to a builder rather than relying on the builder to design a locomotive. Here, four locomotives are seen at Kinsman Yard in Cleveland. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

It might be crew-change time at Kinsman Yard in Cleveland, or perhaps the engineer is receiving instructions on what move to make next. No. 7247 is an N1s for PRR Lines West for drag-freight service, hauling heavy trains of coal and iron ore to and from Lake Erie ports. The PRR had 60 of this model, and all were built between 1918 and 1919. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

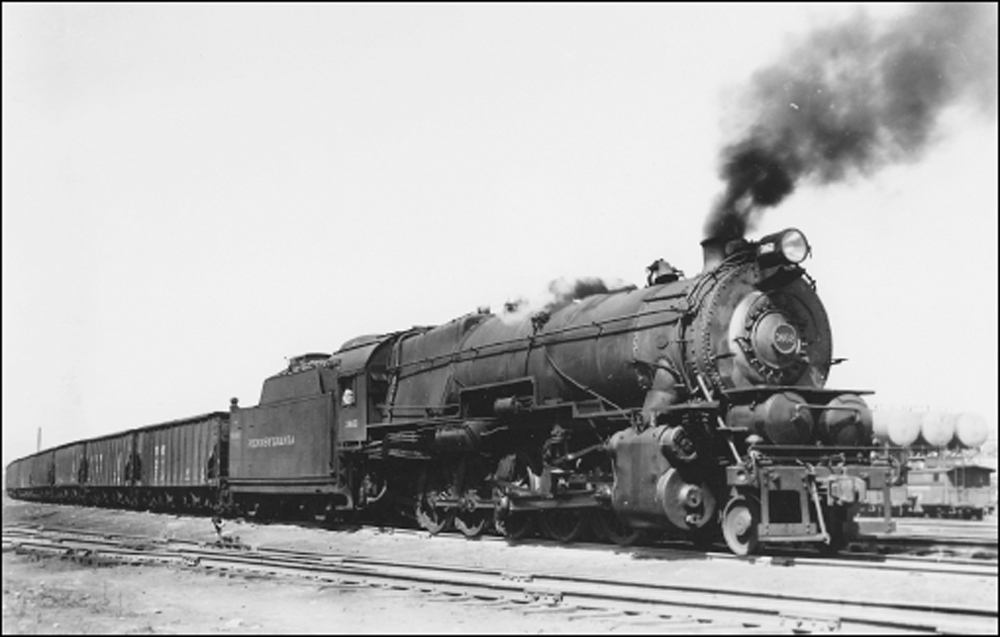

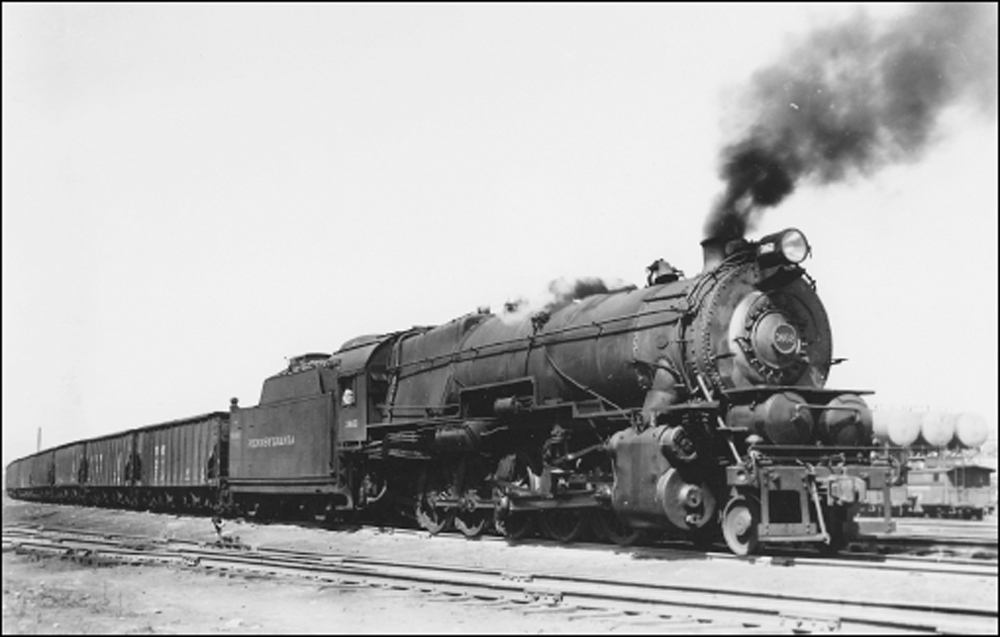

The C&P pioneered the use of coal for fuel in steam locomotives. Its first train pulled by a coal-burning locomotive left Cleveland in 1856, and coal soon supplanted wood as the fuel source for steam locomotives. The C&P was also a major hauler of coal from eastern Ohio mines to Cleveland industries and for loading on Lake Erie freighters. No. 3462, a 2-10-0 Decapod, hauls a train of hoppers. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The M1-class 4-8-2 of the Mountain type that the PRR ordered for use on freight or passenger trains was most often used to pull fast freight trains. Because they could be assigned to passenger service, the M1 locomotives received keystone-shaped number plates. The PRR owned 301 of these locomotives, and some were still operating when the railroad phased out steam power in 1957. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

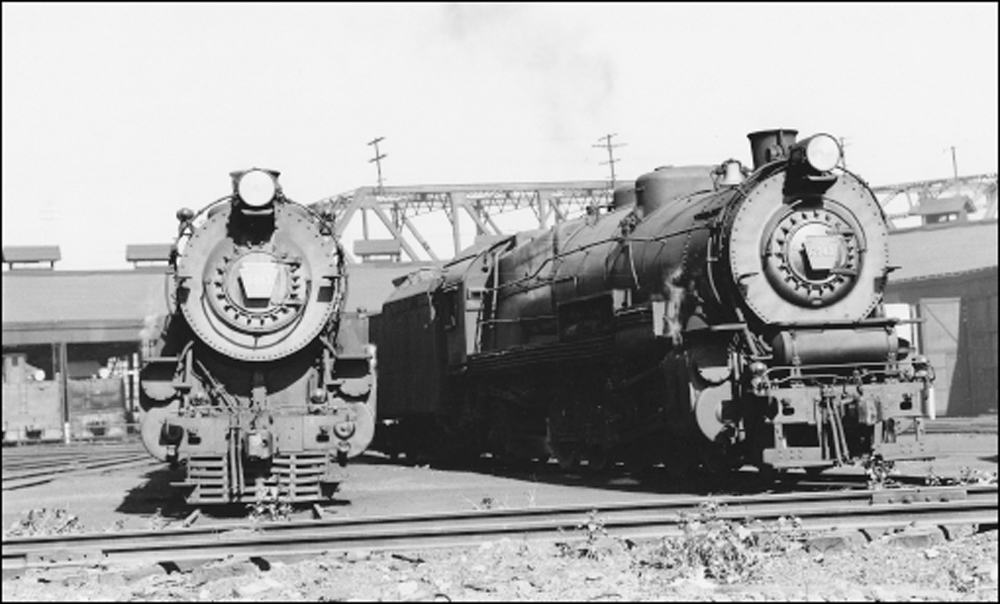

Kinsman Yard was the PRR’s primary Cleveland classification facility. Located six miles southeast of downtown Cleveland, the 70-track yard classified merchandise freight. Situated on both sides of the mainline, Kinsman had a roundhouse and coal dock for fueling steam locomotives. Passenger locomotives serviced here were required to leave at least one hour before the scheduled departure of their train. Inbound trains received at Erie Crossing Tower a track assignment for working at Kinsman Yard. After the PRR merged with the NYC, Kinsman was closed by 1970, and all of the tracks and service facilities were removed. PC consolidated most Cleveland classification activity at the former NYC Collinwood Yard. Shown above at the roundhouse are Nos. 5461 (a K4s 4-6-2) and No. 6941 (a 4-8-2 M1). In the photograph below is No. 7472, a 2-8-0 H-class locomotive. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Most PRR Cleveland passenger service operated to Pittsburgh, although one train, the Clevelander, ran between Cleveland and New York with through sleepers for Washington, DC. Following World War II, the PRR upgraded its premier passenger trains, including the Clevelander, by giving them diesel locomotives and lightweight passenger cars. At the same time, the PRR spruced up two pairs of Cleveland-Pittsburgh trains, naming one pair the Morning Steeler and another the Evening Steeler. The budding interstate-highway system and airline competition ate into the PRR’s passenger business in the late 1950s. By early 1960, the Steelers were gone, leaving the Clevelander, Nos. 38 and 39, as the last PRR passenger train in Cleveland. The Clevelander made its last Cleveland-Pittsburgh runs on April 25, 1964. A Cleveland-Youngstown remnant of Nos. 38 and 39 last operated on January 29, 1965. (Both, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The K4s-class locomotive was the PRR’s standard passenger locomotive. The PRR operated 425 of these Pacific-type locomotives, 349 of which were built in the railroad’s Juniata shops in Altoona, Pennsylvania, between 1917 and 1928. K4s locomotives remained in service until the PRR ceased using steam locomotives in 1957. No. 8261 is shown leading a six-car train on the Cleveland Line in the late 1930s. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

The PRR had two routes between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Most trains operated on PRR rails via Alliance. However, some trains diverged at Ravenna and used B&O tracks to Niles Junction before getting onto the PRR’s Ashtabula-Youngstown Line. Those trains made stops in Youngstown. The Clevelander operated via Youngstown, but the Steelers ran via Alliance. A four-car train is shown in Cleveland passing the Mooney Iron Works. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Nos. 252 and 253 were all-stops locals between Cleveland and Alliance that operated on commuter schedules. No. 253, shown on June 28, 1935, in Cleveland, departed Alliance at 7:15 a.m. and arrived in Cleveland just before 9:00 a.m. No. 253 was later renumbered and continued to run from Alliance to Cleveland until October 23, 1959. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

Beginning in the 1920s, some railroads assigned self-propelled passenger cars to lightly patronized branchlines. Nicknamed “doodlebugs,” these cars used gasoline to turn a generator that sent electricity to the traction motors that propelled the car. The PRR used doodlebugs in shuttle service between Akron and Hudson, the latter being a stop for Cleveland Line passenger trains. A doodlebug with a trailing coach is shown in Cleveland on May 11, 1940. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

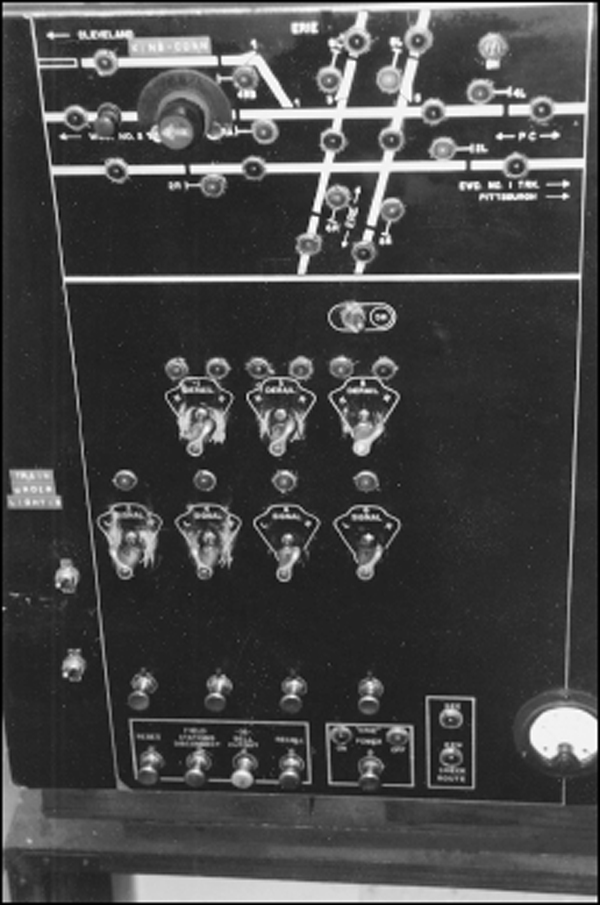

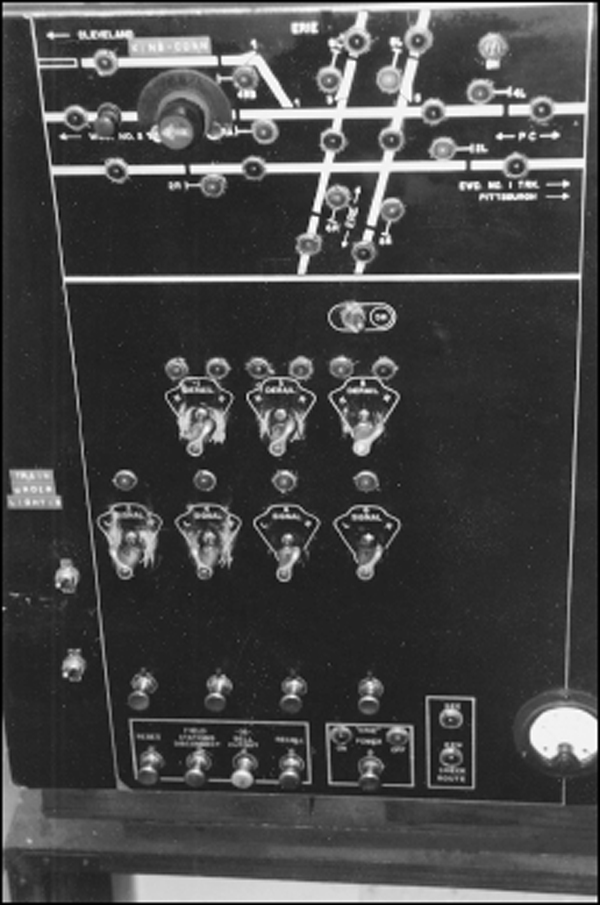

The PRR had a series of interlocking towers on its Cleveland Line that controlled the switches and signals at junctions with other railroads and at crossovers from one track to another. Shown at right is a portion of the interlocking machine used at Harvard Tower, which was located at the junction with the Newburgh & South Shore Railroad and the Wheeling & Lake Erie. This particular machine controlled the crossing of the PRR with the Erie. (Photograph by Craig Sanders.)

The PRR maintained a 15-track yard in Bedford in which to store empty hoppers and iron-ore jennies until they were needed at the ore dock on Whiskey Island. Farther south was Motor Yard in Macedonia, which was established in 1954 to serve a Chrysler Corporation stamping plant at Twinsburg and a Ford Motor Company stamping plant in Walton Hills. Shown is No. 7722, an 0-6-0 switcher. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

In the years before the PC merger, PRR diesels had a bare-bones appearance, with some newly delivered locomotives wearing little more than a number and PRR keystone logos. Gone was the attractive look of Tuscan red and pinstripes. Reportedly, this was done in anticipation of the merger with the NYC. In the photograph above, No. 7082 sports a rather plain appearance. This GP9 was built by EMD in 1956. The GP designation stood for “general purpose,” whereas an SD designation meant “special duty.” The GP models were often called “geeps.” In the photograph below, it is July 13, 1968. The PC merger is barely six months old, and already this former PRR RS-11 has received its PC number of 7635. Built in May 1957, this locomotive wore No. 8635 before the merger. (Above, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections; below, photograph by Robert Farkas.)