7

NOTATIONS

Stephen Davies

The oldest musical instruments date to about 30,000 years ago (bp), but musical notations did not arrive until much later. The first notations date from 4500– 3000 bp in Sumeria and 2400 bp in China, but those with which Westerners are most familiar emerged in Europe around 1200 bp. The earliest European notations assisted singers to recall plainsong melodies by showing the direction and approximate interval size of melodic movement. In other words, these notations belong to the type below called “mnemonic”; they underspecified the melodies they indicated, but showed enough to bring the melody to the mind of someone who was already familiar with it. Subsequent changes to the notation over several centuries (stave lines, indications of relative duration, etc.) permitted a more precise specification of the musical notes and how they are to be sung or played.

It is not necessary to have notation in order to develop a large corpus of works (as the liturgical tradition shows) or to produce long and extremely complex works (as is apparent in Javanese and Balinese music – notations of such music are primarily archival in function and are not usually consulted by practicing musicians). Nevertheless, it probably helps. Singers and musicians in Europe from the fourteenth century or earlier played from notations and were expected to be literate. Works were often issued as part books – that is, as showing the part for each instrument or singer separately – rather than as scores showing all the parts in vertical alignment. Some part books were arranged such that the parts could be read by musicians facing each other, with the book between them. As musical works became more complex and were specified in more detail, scores became more prominent, as did the orchestra’s director, who was usually one of its members but later, from the nineteenth century, a conductor.

Generic and instrument-specific notations

One distinction that is sometimes drawn is between generic and instrument-specific notations. The former show the result to be achieved but not the manner of doing so, whereas the latter indicate the manner of eliciting the desired result from the given instrument. Notations of vocal music are generic: they present what is to be sung and not how to arrange one’s larynx so that the desired sound issues from it. The best examples – indeed, perhaps the only plausible ones – of instrument-specific notations are tablatures for stringed instruments, such as the guitar and lute. (Some of the oldest are for the Chinese quin.) Tablatures show the position of the fingers on the instrument’s strings (or, if it has them, frets) and assume or specify a particular tuning of the strings.

The generic notation of pitch might take several forms. It could be that (more or less) absolute pitch is shown, usually involving reference to some standard and presuming certain tonal or modal systems. Modern Western notation is of this kind. Alternatively, a pitch is indicated as relative to an unspecified tonic in a tonal or modal system. Modern solfeggio – the naming of the notes of the scale, as in “do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do” – takes this form. In this system, the “do” is movable but always counts as the tonic. Or relative position in a series of intervals or a scale could be specified. This is the case with Balinese solfeggio. The notes are named “deng, ding” etc. and the intervals are fixed, but any note in the scale could function as the tonic. (The same applies if “do[C]-re[D]- ” is used to notate the church modes, since in these the degree of the scale that serves as the tonic varies with the mode.) The notation of music for the Chinese shamisen shows intervals (ma) rather than pitches when the instrument accompanies a vocalist, because the singer chooses the song’s pitch according to his range. Early Indian and Arabic notations employed forms of solfeggio. Cipher notation, in which notes are assigned numbers, is similar to solfeggio and was widely adopted in China, India, and Indonesia 150–100 years ago.

Rather than pitches, the notation might show the harmonic sequence according to its chord type. The notation might be absolute (C, a, F, G7, C) or relative to a tonal (or modal) system (I, vi, IV, V7, I), possibly leaving the pitch of the tonic unspecified. A more complex system could imply the bass line by showing the chords’ position/inversion (I, vib, IVc, V7 b, I) or the bass line could be explicitly written with numbers indicating the scale degrees above the bass line of the harmonic middle voices, as in the Baroque “figured bass.” Yet more detail would be added by combining pitch and harmonic notation to show a melody and its harmonic accompaniment.

The generic notation of rhythm, rather than showing measures of absolute duration, usually employs a notation for sounded beats (and rests) and their simple multiples and subdivisions (2, 4, 8, 16, 32 or 3, 6, 12, 24). Where groups of beats are organized according to a meter, this might be specified and indicated by bar lines. (If the meter is regular, it is usually indicated only at the outset.) Alternatively, bar lines could be used as a navigational convenience to check for coordination but without implying a meter or stress. The pace of the underlying pulse can be specified, either with somewhat vague verbal terms (andante, walking pace) or by metronome markings, but even where there is no explicit indication, usually a tempo (fast, slow, etc.) is implied.

One might have supposed that instrument-specific notations preceded generic ones and that a move from one to the other went with a move toward the standardization of instruments and their combination into various ensembles. There is no evidence for this hypothesis, however, and it is unlikely to be true. The first notations came well after moves to regularize instruments and their combination. In any case, if much of the music first indicated notationally was vocal, as seems likely, we can anticipate that generic notations would be to the fore from the outset.

Generic notations have some obvious advantages. If many instruments play together, generic notation makes it simpler for the composer (or conductor) to grasp how their parts fit together. Such notations are more transparent. And they also facilitate the circulation of pieces from one kind of instrument to another, which is certainly valuable if the composer cannot be sure what resources will be available for the presentation of his work. These advantages can be inappropriately exaggerated, however. As I now discuss, predominantly generic notations quite commonly do not show what is to be done in a literal or translucent fashion.

The fact is, notations are neither purely generic nor purely instrument-specific. If tablatures show rhythmic values, as those for lute usually do, these are indicated in a manner that is not lute-specific. The notation of the relative duration of notes and of rests was standardized from the earliest times. Meanwhile, generic notations constantly employ instrument-specific directions if the desired instrumentation is indicated. Sometimes special notational symbols are used, such as that for a down-bow. In other cases, a written instruction is given, such as pizz. (for pizzicato) or sul ponticello (which means play with the bow close to the bridge). There are literally dozens of terms and symbols dealing with the manner of using the bow, for instance. Obviously, these instructions are addressed to string players; wind instrumentalist do not use a bow and have no strings to bow or pluck. In a similar vein, organ music includes instructions for preferred couplings (resulting in doubling at the octave, for instance) and stops (that reproduce the timbral effects of specific instruments or the voice). Piano music may include specifications about the use of the pedal; harps have seven pedals each of which has three positions and idiomatic harp writing usually indicates how they are to be used.

Sometimes a notational element that appears to be generic because it is addressed to very different kinds of instruments in fact requires modes of execution that are instrument specific. A good example of this is the instruction con sord (which means play with a mute). The mute on a stringed instrument is a clamp that attaches to the bridge and dampens the instrument’s resonance. By contrast, mutes for brass instruments are cones or hats placed in or over the instrument’s bell. Some wind instruments can be muted, though this is not common, by the insertion of a cloth in the instrument’s bell. These instrument-specific means of quieting the instrument result in distinctive modifications to the instrument’s timbre, and it is these effects, rather than quietness alone, that are often sought by the composer. Another example is the instruction tr. (for “trill”). Addressed to an untuned percussion instrument, a roll is called for, whereas a violin rapidly alternates notes at the interval of a semitone or tone, depending on the context.

Another implicitly instrument-specific aspect of standard notations is in the use of clefs. The piano made the use of a G (treble) clef and F (bass) clef standard, with the two sharing middle C one ledger line below the treble clef’s five stave lines and one above the bass clef’s five stave lines. The parts for most instruments nowadays use one or other of these clefs (sometimes with a transposition up or down an octave, as with the piccolo and double bass). In the past, C clefs, placed variously in relation to the stave’s lines, were more common. (This practice apparently did not inhibit the readability of the various parts in vertical relation, from the composer’s point of view.) Their use survives for a few instruments. In particular, the viola alone uses the C alto clef (with middle C as the stave’s middle line). In their upper ranges, the bassoon and trombone (and less often the ’cello) use the C tenor clef (with middle C on the fourth line of the stave). Presumably, these usages hark back to earlier periods in which certain kinds of instruments were viewed as forming families with ranges overlapping at the fourth and octave.

It was formerly common to produce a kind of instrument as a family or choir, with each individual within the family tuned a fifth or fourth from its nearest siblings. Viols, for example, were arranged as a consort. (The only member of the viol family surviving to the modern orchestra is the double bass.) Recorders were tuned as follows (high to low): garklein (C), sopranino (F), soprano (C), alto (F), tenor (C), bass (F), great bass (C), contrabass (F). In this case, the tuning indicates the instrument’s lowest note, with the tenor’s being middle C. It is not common for modern instruments to retain the full choir – for instance the flute (C) is usually accompanied only by the piccolo (an octave higher but lacking the lowest C) and the alto flute (a fourth lower, to G) and the oboe is paired only with the cor anglais (a fifth lower at F) – but the saxophone is an exception with sopranino (E-flat), soprano (B-flat), alto (E-flat), tenor (B-flat a major ninth with below middle C), baritone (E-flat), bass (B-flat), contrabass (E-flat).

It is useful for the musician to be able to swap from one instrument to its siblings. To facilitate this, the note designations of the fingerings were kept the same. For example, if the second oboist took up the cor anglais, she would finger a notated C as she would on the oboe, but the note sounded would be the F below this. Or in other words, the notation of the part was transposed up a fifth, so that she could treat the two differently pitched instruments as using a consistent fingering. This flexibility and convenience compromises the clarity of the notation, however. It results in notations showing pitches and keys other than those literally sounded. Moreover, where this occurs the pattern is not systematic because many instruments employing different transpositions may be in simultaneous use. Though the notation has the appearance of being generic and is certainly not instrument-specific, it is significantly affected by the practice of playing that goes with different kinds of instruments.

Transposing instruments as they are called – that is, instruments whose parts are notated at a pitch other than the one sounded – do not always divide up the pitch range so neatly as the recorder or the saxophone. Soprano and sopranino clarinets come in many pitches. Meanwhile, the player of the main clarinet part has two instruments – one transposing to B-flat and the other to A. In other words, a B-flat clarinet sounds a B-flat when the musician fingers what is notated as C, and the A clarinet sounds an A when the musician uses the same fingering, also notated as a C. The B-flat clarinet is better suited to flat keys (it cancels two of the flats in the key signature) and the A clarinet to sharp keys (it cancels three of the sharps in the key signature). No doubt historical contingency played a major role in bringing about this musical anomaly, but one reason for it might have been to avoid forked or half-hole fingerings, with their uneven tone and timbre, which would have been unavoidable for sharpened and flattened notes prior to the introduction of the modern Boehm system for woodwinds, which addresses the problem by adding supplementary holes activated by metal keys.

Prior to valves and slides, brass instruments could play only the fundamental and the natural harmonic series above it (and, for horns, a few other pitches half-stopped with the fist), where the pitch of the fundamental was determined by the tube’s length. To get around the limitations this caused on the number of keys in which the instrument could play, it was common to insert “crooks,” extra lengths of tubing that altered the instrument’s fundamental. Again, pitch was notated as if no crook was in use, and the part was transposed to take account of the crook’s effect. The modern introduction of valves did not remove the need for transposition: most brass instruments transpose to B-flat or E-flat. Indeed, the modern French horn in effect conjoins two horns tuned to F and B-flat, and the notational conventions for the instrument are unique, with the part notated a fifth higher than it sounds in the treble clef but a fourth lower in the bass clef.

One final use of instruments that leads to the transposition of the notation of the instrument’s part is scordatura, in which there is some departure for a stringed instrument from the standard interval or pitch tuning of the strings. Because the musician is trained to finger the instrument in the normal fashion in producing what is notated, to keep a scordatura part in tune with other instruments the part must be notationally transposed or altered to take account of the unusual tuning.

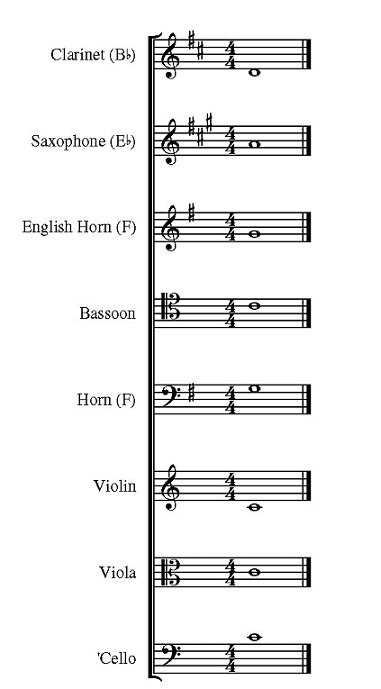

In a normal orchestral score, the parts of a number of the instruments will be transposed, so that the pitches that are written are not the ones that are sounded (Figure 7.1). This undermines one of the advantages of a generic notation, namely, transparency across the parts of the score, and shows how the practical business of dealing with the instruments shapes the notation, even where the notation is not entirely instrument specific in design. Of course, one obvious response to this would be to show all parts in a score at their sounded pitch; the score’s indication of the cor anglais’s music, say, need not duplicate the part from which the relevant musician plays. This has yet to become the general practice, though, perhaps because it could make communication between the orchestra’s director and the musicians difficult or ambiguous.

Because notations are not always to be read literally, their proper interpretation relies on knowledge of both the conventions of the notation system and the background of musical practice it takes for granted.

Functions of notations

We might prefer to classify notations not in terms of their appearance but of their function. A first type was mentioned earlier: mnemonic notations. These are sketchy or gappy notations that serve either to remind the musician of something she knows or to provide something from which she can derive her part. Examples of the latter, perhaps, are Indonesian notations that indicate the melodic spine of the piece, since other instruments improvise around that spine or can derive their parts from it, or, in jazz, a notation of a chord sequence or melody that is the basis for an improvisation. Mnemonic notations do not always go with free or improvisatory pieces. Long and complex pieces can be committed to memory and recalled with great accuracy once the necessary notational (or other) cues are presented, as is apparent in traditions of liturgical chant or in Balinese music.

In the West, a primary function of notations has become that of specifying works. Such notations have a prescriptive force: if you would play my work, make this so! The interpretation of work-specifying notations requires some care: as well as knowing the general conventions of the notation and the practice it assumes, one needs to be aware of others specific to the kind of work notated. For instance, it may be that not everything that is required in delivering the work is indicated in the notation – perhaps melodies must be decorated when repeated. And it may be that not everything that is notated is prescribed, as against recommended – perhaps marked repeats, phrasings, and fingerings are optional.

Such scores can include comments or programs that are not addressed to the performer as such. These, if not solely for the composer’s benefit, are usually addressed to the work’s listener. Also, the notation might be written so as to have, in addition to its musical import, a pictorial significance. For instance, the notes might be so disposed in the score of a passion to look like three crosses. (Some fifteenth-century composers created “eye-music” in which visual aspects of the score were relevant to the music’s subject. A famous example of c.1400 is a love song by Baude Cordier in the Codex Chantilly, which is notated in the shape of a heart.) Whereas the visual aspects of concrete poetry surely are to be counted as among the work’s elements, the same does not apply here: the score is not the musical work as such and the pictures in the score rarely generate equivalent “aural pictures” when the music is played. Such notational tricks have their interest, of course, but they belong with many other techniques and devices – such as the creation of long-distance derivations and relations between bits of the work – that structure the composer’s efforts without being audibly discriminable in how the work sounds.

The use of pictorial elements in scores is not always incidental, however. In the early days of electronic music, pictorial impressions of the music’s sound were issued as “scores.” From the composer’s point of view, this was no idle matter because the law at the time allowed works to be copyrighted only via their notational specifications. And in the 1950s, some composers addressed performers not with standard notational instructions but with pictorial impressions of the sounds they desired the performers to realize. An example is Earle Brown’s Folio of 1952–53. In such cases, the performer may have considerable freedom not only in the manner of her interpretation of the work but also in her interpretation of the notation that specifies it.

A further principal function of notations is to document musical events. Such notations, known as transcriptions, are descriptive, not prescriptive; they are usually based on a single performance and record what was done. A performance can present more than one musical object: a work (if there is one), a repeatable interpretation of a work (if there is one), and a singular musical event of playing. A documentary notation can target any of these. Musical works can be more or less thick or thin with constitutive detail – one requiring sections of improvisation is thinner than one that indicates each and every note that is to be played – but even in the case of the thickest works for live performance, their renditions always contain sonic detail that is attributable to the performer’s interpretation rather than to the work itself. That is, even the most complex notational specifications of the thickest musical works leave many choices to the performer’s discretion, as regards both microscopic features, such as phrasing nuance, and macroscopic elements, such as shaping, contrasting, balancing, and emphasizing. Accordingly, a notation intended to capture only the work recovers less detail than one intended to display the performer’s interpretation of the work. And whereas both of these may involve the notational correction of what were performance errors, a notation attempting to record the microscopic detail that marks the single performance as an unrepeatable individual act of playing does not. Transcriptions of this third kind are rare, however, because standard musical notations, even when supplemented with specially defined symbols, are not fine-grained enough to capture the shadings of pitch, timbre, attack, rhythmic inflection, etc. that are crucial to the individuality of a single live musical rendition.

Functions apart from these three are served by some musical notations. Notations can be used for pedagogical purposes: for teaching the use of the notation, the playing of musical instruments, orchestration, and so on. As well, musical analysts and historians of music use them to illustrate their accounts. Composers sketch their ideas, doodle, and write drafts of works. These further uses are obviously secondary and derivative.

Nelson Goodman on musical notations

Nelson Goodman is among the few philosophers to have discussed musical notations. He focuses on the work-identifying function of scores and holds that they must uniquely and unequivocally describe the work they specify. To do this the notational system must meet two syntactic requirements – disjointness and finite differentiation – and three semantic ones – unambiguity, disjointness, and finite differentiation (1968: 130–52). The syntactic conditions are met when each notational mark belongs to one and only one “character” (that is, each symbol denotes only one musical element or event). The semantic conditions are met if the notation is unambiguous, all work-relevant musical elements are notationally specifiable, and no two distinct scores could have any accurate copies or performances in common. According to Goodman, a performance must comply exactly with the score to instance the work it specifies and the score must be derivable from a genuine instance of the work.

At first glance, it looks as if Goodman will have to regard as notationally satisfactory only those scores that spell out each and every work-identifying detail that is to be played in instancing the work. A score that invites the performer to decorate melodies when they are repeated, for instance, will lead to non-identical renditions from which a single score is apparently not derivable. Goodman avoids this difficulty by distinguishing different systems of notation, with any given work relativized to only one of these. Provided the instances of a given work form a class that is distinct from the classes of genuine instances of all other works specifiable under the same notational system, it does not matter that the instances comprising the class of the given work vary in respects allowed for within that notational system. For example, though a trio sonata with a figured bass tolerates more than one realization of its middle parts, we could derive a score of the work from any accurate performance provided that we were aware that the work belonged to a notational subsystem allowing this mode of improvisation. Such a work would be distinguishable from different trio sonatas that also use a figured bass. Moreover, though works relativized to a different notational subsystem (for instance, to one that spells out the middle parts and does not permit improvisation) might happen to have compliants intersecting with those of the trio sonata (and hence violating the condition for disjointness), this appearance is illusory given that work identity is a function of the notational subsystem under which the work-identifying inscription falls.

Goodman is not always so accommodating, however. For instance, he regards verbal tempo indications, such as largo, as non-notational because they are ambiguous and not finitely differentiated. In dismissing such markings as non-notational, he removes tempo as a work-identifying feature. A genuine performance for such a work might have any tempo, including one so slow as to make the piece unrecognizable. Similarly, the mark tr. (trill) is non-notational because it does not specify how many notes should be played, so a performance of Giuseppe Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata would be accurate, according to Goodman, if it contained no trills.

Goodman’s is offered as an idealized, revisionary account, but to be acceptable it should at least capture many of our central intuitions regarding notationally specified works. If it is to come close to doing so, it will be necessary to assume there are a great many exclusive musical notational subsystems and that we are (or could be) clear on how they differ. Neither assumption is convincing. A more plausible approach is the one advocated earlier. Instead of leaving the notational system to do all the work, so to speak, which means that many distinct systems will have to be recognized, we should acknowledge that general notations are employed according to a spread of historically grounded conventions concerning how they are to be read, established traditions of performance practice, and characteristics of differing work genres or types.

See also Authentic performance practice (Chapter 9).

References

Goodman, N. (1968) Languages of Art, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Further reading

Apel, W. (1953) The Notation of Polyphonic Music: 900–1500, rev. 5th edn, Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America. (The classic treatment of Western early music notation.)

Davies, S. (2001) Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration, Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Chapter 3 is devoted to a discussion of notations.)

Gerou, T. and Lusk, L. (1996) Essential Dictionary of Music Notation: The Most Practical and Concise Source for Music Notation, Indianapolis: Alfred Publishing. (A practical guide to Western musical notation.)

Kaufman, W. (2003) Musical Notations of the Orient: Notational Systems of Continental East, South, and Central Asia, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (A description of some classical non-Western notational systems.)