Birth of the Mazda roadster

The Toyo Kogyo business was renamed the Mazda Motor Corporation on 1 May 1984, with Kenichi Yamamoto elected President shortly after his 62nd birthday. Born in September 1922, the former MD had served Toyo Kogyo for many years, and had been the company’s Chief Engineer since January 1978.

Yamamoto had seen a vast number of changes along the way in both technology (he had been responsible for designing a V-twin engine for the three-wheeled Mazda trucks shortly after the war, and was heavily involved with the R360 and its descendants; he was also one of the key people behind the development of the Mazda rotary engine), and in the growth of the company as a leading car manufacturer. However, behind all of Yamamoto’s achievements in the field of engineering was an underlying enthusiasm for his work – an important factor which would have a bearing on the future.

Kenichi Yamamoto, RJC ‘Person of the Year’ 1991-92, and a key figure in Mazda’s automotive history.

MANA

Mazda (North America) Inc. (or MANA) had a Product Planning & Research (PP&R) arm, which was managed by Shigenori Fukuda. The idea behind this department was that its findings would give Mazda a much better feel for its market, so that future vehicles could be tailored specifically to suit the tastes of different countries.

One of the first Americans to join the PP&R office was Bob Hall, a true car enthusiast with a background in automotive journalism. Hall, having been brought up around British sports cars, was keen on the idea of a modern equivalent. In fact, when casually asked at the end of a meeting with Kenichi Yamamoto in the spring of 1979 (when Hall was still working as a journalist), what he would like to see Toyo Kogyo building, he suggested that Mazda should make a lightweight sports car that would sell at a price even cheaper than the RX-7’s.

On a trip to the 1983 Pebble Beach concours event, Hall soon found he was not alone in this idea. Fukuda, one of the group evaluating the RX-7 in the all-important American market, was asked by Hall what type of car he would like to design next. His reply was “a lightweight sports car.” Naturally, this drew quite an eager response, and Hall’s Japanese soon turned into excited English. Needless to say, by the end of the journey (after Hall had been stopped for speeding as his enthusiasm grew by the mile), Fukuda-san’s English had improved no end!

The MANA team actually drew a diverse range of sports car proposals, but, in reality, it was the lightweight open two-seater that appealed the most.

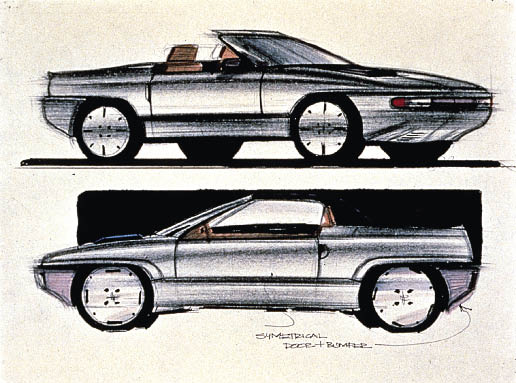

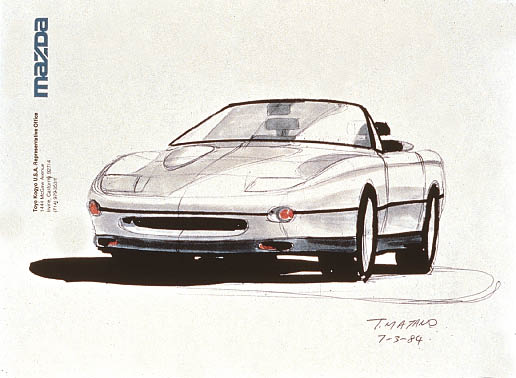

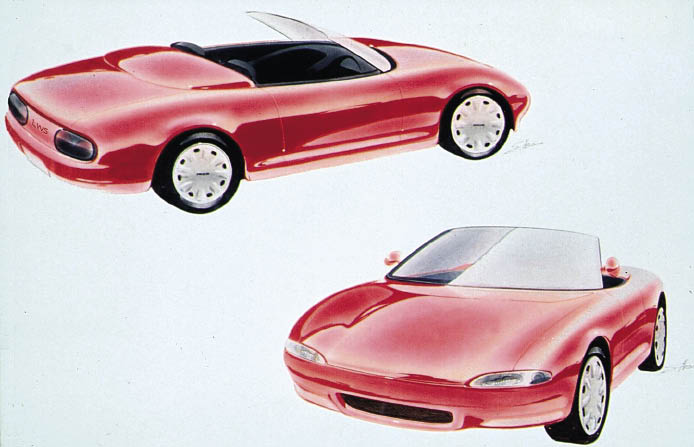

An original design sketch from Tom Matano, dated March 1984.

A roadster with a detachable hard-top in place. A closed coupé was also investigated, at least on paper.

Another of the design drawings submitted by MANA for its ideal lightweight sports car. According to Fukuda-san, hundreds of sketches were produced, a number of the proposals resembling vehicles like the Morgan three-wheeler, Lotus Seven, and the Porsche 550 Spyder.

Not long after this, an appraisal entitled What is a Sports Car to an American? was sent through to Head Office. This was quite a lengthy piece, but the most important paragraphs read as follows: “Sports cars must have a degree of performance, but more importantly, they must be fun to drive. A low-cost sports car doesn’t need 0.81g lateral acceleration or 0-60 in 8.5 seconds. It has to, as one journalist succintly put it, ‘feel faster than it is, but it doesn’t have to be fast in absolute terms.’ Of course, a sports car musn’t be a sluggard either, so it is a classic example of searching for the happy medium.

“Appearance (particularly one’s first impression) and performance are obvious things which make a sports car, but there are a couple of intangibles, too. Not the least of these is image. If you look back in history, all (not some or most, but all) of the successful sports cars have developed a cult-like following of enthusiasts, a core of people who have an almost maniacal enthusiasm for the particular make and model of car they own – MG or Lotus Elan enthusiasts, for example. Most of these people would never race or rally their car, but they won’t buy anything else. This image is essential to a successful sports car. The MGs all had it – Saab’s Sonnet never did. Any TR-series Triumph possessed this element, but try as hard as it could, Sunbeam wasn’t ever able to develop such an image for the Alpine.

“There have also been a lot more successful convertible sports cars than coupés, at least in the United States and Canada. The Opel GT, Marcos 1800, Glas 1700 GT, Lancia Montecarlo (Scorpion in America), Simca 1000 and (in later forms) Saab Sonnet were all pretty, but there wasn’t a convertible (or a success) among them. Even Targas are not open cars to most sports car owners. This is not to say that a light sports car cannot succeed without a convertible [top], but an $8000 convertible among a flock of $9000 –$12,000 coupés and Targas should be as popular as beer at a baseball stadium.”

It was obvious that the people at MANA thought America was in need of an affordable sports car. At this stage in the proceedings, however, nothing was heard from Hiroshima.

An LWS

A friend of the author’s, Yoshihiko Matsuo, Chief Designer of the original Fairlady Z (240Z) and now a design consultant, gave his definition of a modern sports car in a recent interview: “It must be a two-passenger automobile with attractive body styling designed for high speed, highly-responsive driving. The engine must have reserves of power even at high rpm. It should have a manual transmission with a good feel and a fully functional cockpit, and support pleasant high speed handling. To state it as a category, I would say that sports cars belong to a category somewhere between specialty cars and racing prototypes. Also, I believe, there are two main types of sports cars; one the Lightweight Sports Car and the other the Super Sports Car.”

The Mazda RX-7 wasn’t exactly lightweight, but it was nearer the lightweight concept than most. Weighing in at around 1100kg (2420lb), it was substantially lighter than Nissan’s S130 series Fairlady (280ZX), and the recently introduced Z31 models. But the RX-7 was destined to follow the Fairlady in its move upmarket: the P747 would be bigger, faster, heavier, and better-equipped. In other words, the second generation RX-7 was going to be a Super Sports Car.

The first generation RX-7 sold in massive numbers in the States, just like the original affordable Japanese sports car of the Seventies, the 240Z. The Toyota Celica was another success story. Of course, exchange rates at the time helped, but these cars were not the pure flukes some would have you believe – nothing in Japanese business happens by chance. By careful research, the Japanese had found the formula: offer excellent value-for-money in an attractive, reliable package, and it’s a licence to print money.

However, with the new RX-7 scheduled for the 1986 model year (work had started on it in 1981), this was going to leave a void in the market as far as Japanese manufacturers were concerned. Toyota immediately spotted this niche and tried to fill it with the mid-engined MR2, but in America – the world’s biggest sports car market – it was not as successful as was hoped, probably because Pontiac brought out the Fiero just beforehand. Honda also saw the gap and launched the sporty front-engined, front-wheel drive CRX, but this could never be considered a true sports car in the great tradition of the S500, S600 and S800 roadsters.

The Mazda marque was flying high in the States at that time, with the RX-7 dominating the IMSA racing scene and the SCCA Pro-Rally series. Kenichi Yamamoto knew that a true LWS – an abbreviation of lightweight sports car, a term used within the trade in much the same way as MPV (multi-purpose vehicle), and so on – would potentially have the market to itself and further strengthen Mazda’s sporting image.

Yamamoto had got the sports car bug after Hirotaka Tachibana of the Experimental Department and Takaharu Kobayakawa (one of Yamamoto’s most respected engineers who had been Chief Engineer on the RX-7 since 1986) – both LWS enthusiasts of the highest order – had encouraged him to take a business trip to Tokyo via the mountain roads around Hakone in a Triumph Spitfire. After this, he knew that Mazda should try and develop a similar vehicle. Judging by MANA’s essay sent to Hiroshima in 1982, the staff there also thought the market needed an entry level sports car as well.

The Mazda Technical Research Centre in Hiroshima was still in the planning stage (it opened in 1985), so as something of a stop-gap, in November 1983, the company established a programme to allow its designers to think up and develop ideas for vehicles outside their recognised range. This programme was given the bizarre name, ‘Off-Line, Go, Go’.

Michinori Yamanouchi, Mazda’s Managing Director, hoped that this programme would encourage the engineering and design staff to take a fresh approach and, indeed Off-Line, Go, Go (or OGG) elicited some novel proposals. The subject of this book was one of the projects to be tackled off-line - a lightweight sports car.

A competition

Once the LWS project had been chosen, there was the matter of which layout to go for. It was decided that the three main possibilities – FR (front engine, rear-wheel drive), FF (front engine, front-wheel drive), and MR (mid-engine, rear-wheel drive) – would be split so that each idea could be developed properly. After some far from subtle hints, the FR layout went to MANA in the States, while the FF and MR cars were assigned to the Tokyo Design Studio in Japan. The resulting designs would then go through two rounds of judging in Hiroshima and, ultimately, a winner declared. Masakatsu Kato, who was behind many of Mazda’s concept cars, was given the task of overseeing the project, code number P729.

Although there were no firm plans for the LWS as yet, Mazda was seriously considering producing a Familia Cabriolet. Mark Jordan, who had joined MANA in January 1983, was put in charge of the project. The son of Chuck Jordan (the head of design at General Motors), he came from talented stock. A car was duly built, and the model eventually joined the Mazda line-up.

However, the team at MANA was far more interested in the LWS project. By this time, Fukuda, Jordan, and stylist Masao Yagi (Fukuda’s assistant who had been sent to the States from Hiroshima), had already began working on their ideal open sports car. Tsutomu (Tom) Matano joined MANA at the end of 1983 as head of the design section, having previously worked for GM and BMW, earning an excellent reputation along the way.

Tom Matano wasn’t particularly happy with the facilities at MANA when he first moved there (most of MANA’s money at that time came from fitting air conditioning units bought in the States), although the LWS project that he took over had great appeal. “When I joined Mazda,” he said, “the first project I worked on was the Miata, and I thought this was a good chance for me to really put my emotions and passions together to make a car.”

Having said that it was the Bertone-styled Alfa Romeo Giulia Canguro of 1964 which inspired him to become a car designer in the first place, Matano’s view concerning the background to the project was quite significant: “I think what we’re looking for is the simplicity of the era, say, the Sixties. We want to get back to a relationship between car and driver that simply brings fun [to the owner]. At a time when the British sports cars had all gone ... due to either safety rules or emission rules and so forth, the fun element was really disappearing out of the market. And again, another urge was to provide the type of car that we loved when we were younger ... [We thought] a small sports car with a convertible [top] has to have a place in the future as it had in the past.”

Shortly after Matano joined the team, a layout engineer by the name of Norman Garrett III signed up for MANA as well. Given that the American LWS would use an FR layout (the one preferred by most traditional sports car enthusiasts and the MANA team itself), Garrett decided to use components from the existing range – an old rwd GLC (323) engine and transmission, and MacPherson struts all-round for the suspension.

Although a fresh approach could have been used (that was the reason behind the formation of OGG, after all), it was hoped that by using parts which could be easily sourced from within the organisation, the project stood more chance of being accepted.

Meanwhile, two lightweight coupés were being designed in the Tokyo Design Studio; one, a front-wheel drive model (FF), and the other, a mid-engined (MR) vehicle. The FF design had a distinct advantage, as the 323 was moving in this direction and would make an obvious donor car if the design was allowed to progress. The success of the Honda CRX also helped promote this configuration.

Having been involved with the RX-7, Yoichi Sato was quite keen to produce a car to compete with the CRX, and set about his task with the help of Hideki Suzuki in their small office in the Gotanda district of Tokyo, not far from Haneda Airport. Early drawings included a convertible but, eventually, an attractive coupé was settled on. However, the mid-engined vehicle, with its wedge shape and sharp roofline, was more distinctive. Indeed, when the competitors met for the first round of the contest in April 1984, it was the MR machine that looked the most impressive on paper.

The MANA proposal was not totally without support, though, as Toriyama-san (Mazda’s export man and MANA President) was quite enthusiastic about the open car.

Seconds out, Round Two ...

When the second round of competition was held in August, the FF design was looking odds-on favourite. The MR design, meanwhile, had an uphill struggle on its hands. In reality, it was almost doomed from the start, as Masaaki Watanabe had already built a Familia with the MR layout and declared it unsuitable for production. Extra bulkheads would have insulated the noise and heat build-up, but, naturally, weight then increases as a result. It had dimensions very close to those of the recently announced Toyota MR2, and with the Pontiac Fiero also available, the mid-engined sports car market was probably better catered for than it had been since the 1970s.

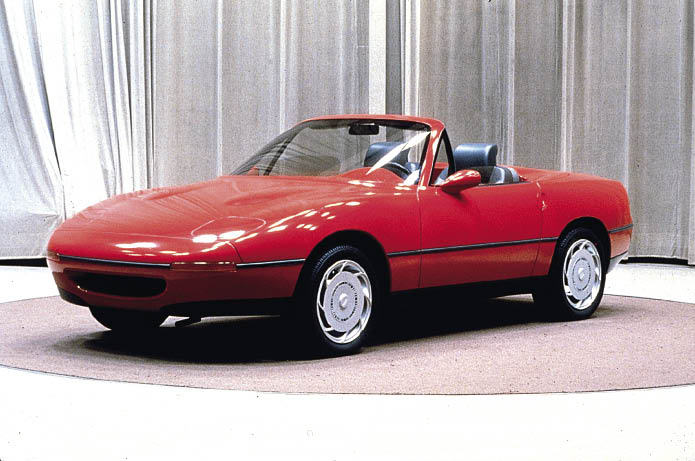

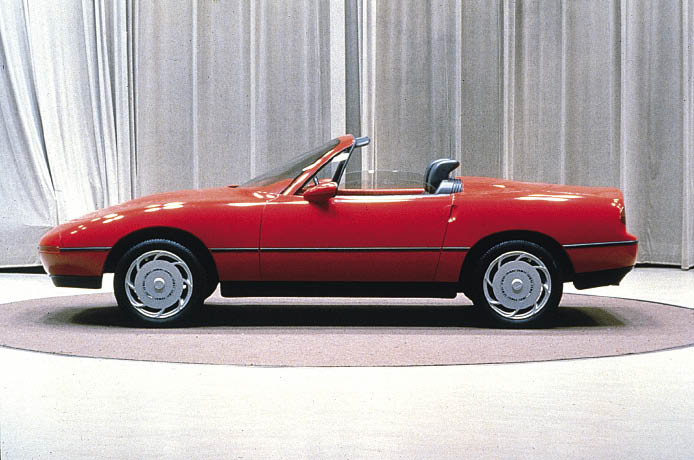

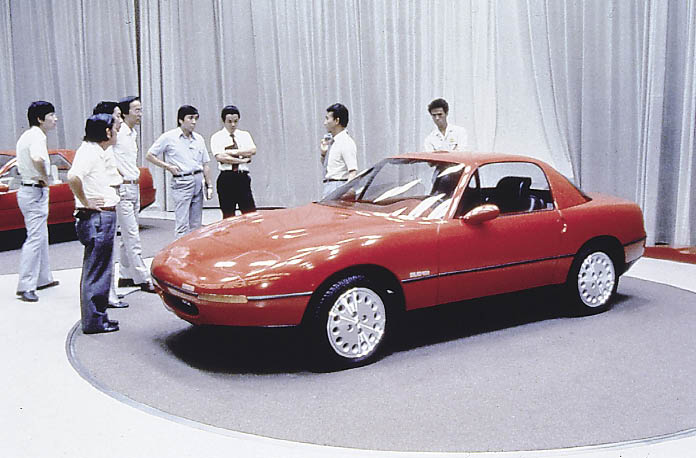

August 1984. The first model from MANA which set the LWS project in motion. Tom Matano said his team had set out “to recapture the spirit of the British sports car,” but no-one could have anticipated at the time the huge success of the subsequent production model.

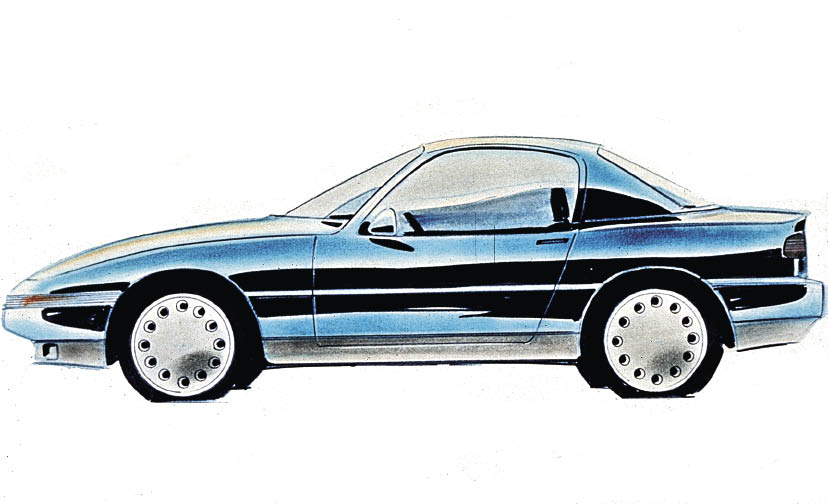

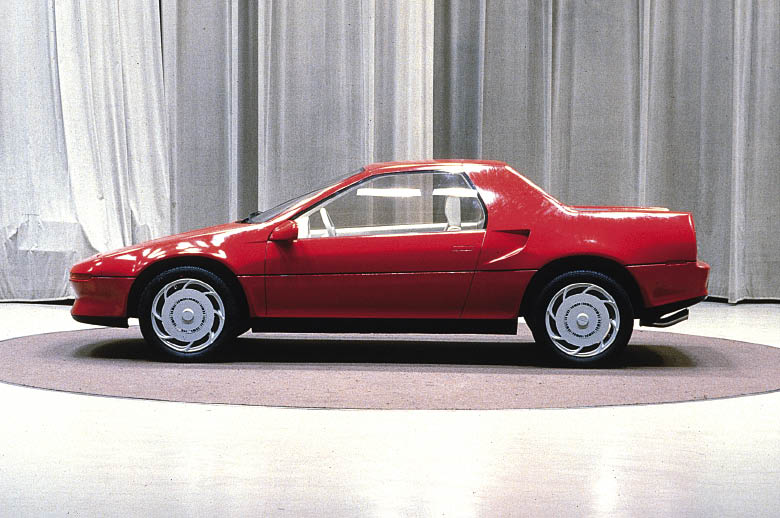

The Tokyo Design Studio’s FF coupé in profile. The drawings based around this layout were perhaps better than the full-sized clay, although the nose was very attractive. A convertible had also been suggested in the early stages of the design process.

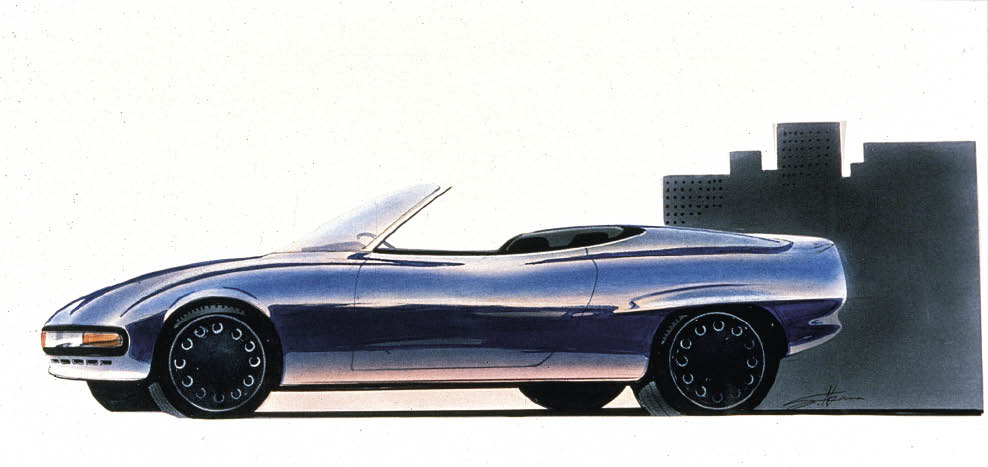

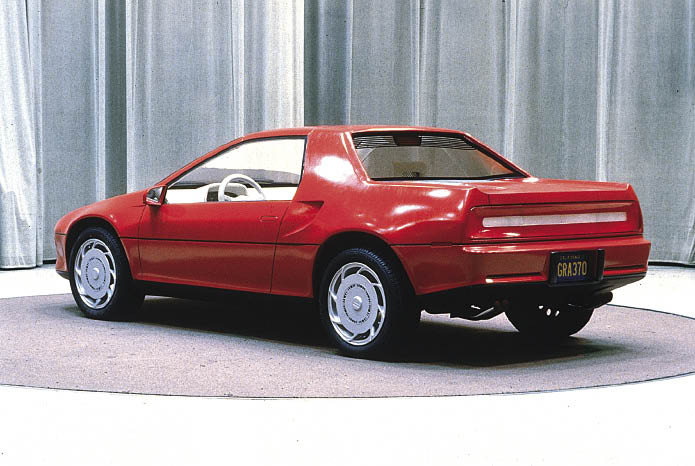

The MR design submitted by Sato and Suzuki. An interesting proposal, the overall dimensions were very close to those of the recently introduced Toyota MR2.

Front three-quarter shot of the MR proposal.

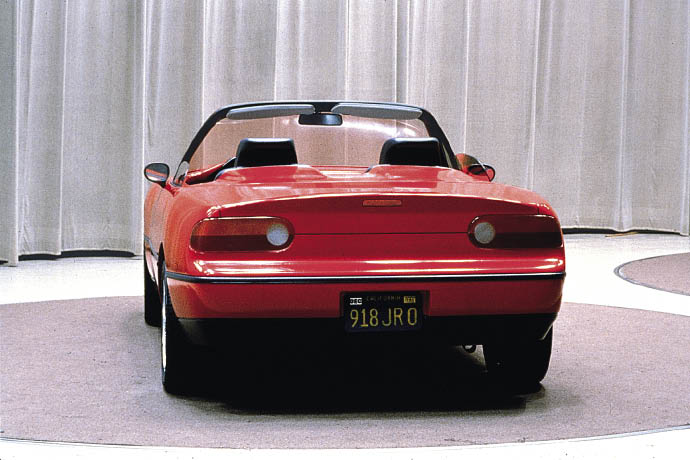

A rear view of the MR model. In fact, the MR layout was always going to struggle, as Masaaki Watanabe had built an experimental mid-engined 323 and dismissed it on NVH (Noise, Vibration and Harshness) grounds.

MANA’s Duo 101 in profile.

A front view of the FR model. Note the stylish air intake and small door mirrors.

The attractive Kamm tail of the Duo 101. Neat touches abound, such as the hidden door releases and the fairing on the rear deck.

The second phase of the competition was to present full-scale clays, and, through this process, the MANA proposal suddenly came alive. Even Sato was impressed, saying: “Their full-size model was a quantum leap from those flat sketches.”

The design (which was actually the first clay to be built at the Irvine studio) was christened the ‘Duo 101’ by the staff at MANA – Duo apparently signifying that either a hard-top or soft-top could be used.

Fukuda and Hall put forward a whole host of reasons outlining why the FR layout was more suitable in a car of this type, and even put together a video presentation to try and sway the judges’ decision. It was a very professional approach which ultimately paid off. The MANA team won and was therefore destined to play an important part in the early stages of Mazda’s LWS project.

The Duo 101 with its hard-top in place. Shigenori Fukuda can be seen in the middle of this picture, draping his jacket over his shoulder.

A brave decision?

The decision to go for the convertible may have seemed a brave move, but, in retrospect, there was an obvious hole in the market. The Alfa Romeo Spider was suffering from a lack of investment and ongoing development, and the Fiat Spider, latterly badged as a Pininfarina model, was about to fade away.

There wasn’t really much else available, unless one was willing to look at low-volume models, special conversions on existing coupés, or very expensive convertibles. But it wasn’t always this way: look in any American monthly magazine from the 1960s and there will almost certainly be more adverts for open British sports cars than for any homegrown products. However, by 1970, British manufacturers had completely lost their stronghold on the American market.

Forthcoming Federal regulations seemed to signal the end of the convertible, but it’s much too easy to cite this as the sole reason for the extinction of the cheap sporty models eminating from UK shores. In fact, a number of factors contributed, with the car builders having to take at least some of the blame for poor build quality, archaic specifications, and a distinct lack of customer care.

Reliability problems were another factor. The author has owned a string of cars which would appeal to the enthusiast, so can confirm as well as anyone that the occasional problem is accepted and passed off as thoroughbred temperament. However, after a while it soon becomes wearing, and, with the introduction of the Datsun Fairlady roadsters (and then the legendary 240Z), many sports car enthusiasts were converted to Japanese products which not only spent more time on the road instead of in the garage, but also offered exceptional value for money.

This spoilt the Americans, who witnessed the qualities of Japanese cars in SCCA racing as well. When the Triumph TR7 eventually became available as a convertible (it was designed as a pure coupé from the start as it was thought soft-top cars would be banned in the US), an American magazine carried out a loyalty survey to see if existing owners would buy another. In stark contrast to cars like the 240Z and RX-7, the results were some of the worst recorded. In Europe, too, although sports car buyers were a little less receptive to these Oriental impersonators, the Japanese were certainly making inroads.

Japan had not built many convertibles since the war, and most of them from the early 1980s were coupés converted to cabriolets by third parties. Avatar did this with the first generation RX-7 before Mazda produced its own convertible on the second generation RX-7. Other notable examples included ASC’s work on the Celica, and Richard Straman’s 300ZX and cheap little roadster based on the Honda Civic. Interestingly, all of these conversions were carried out in North America.

Looking further back in history, the Datsun DC-3 was probably the first purpose-built Japanese convertible, sold during 1952. Nissan built a few soft-top prototypes before launching the Datsun Fairlady Roadsters. There was also a prototype 240Z drophead, which, sadly, failed to make it into production due to proposed Federal regulations threatening to stamp out open cars. There was also the Mikasa, but very few were sold. Other rarities included the Prince Skyline Sport Convertible and Daihatsu Compagno. Honda built a run of successful roadsters, and Toyota took the roof off a 2000GT for a James Bond movie, but it wasn’t until the third generation Celica that Toyota listed a convertible in its line-up. The examples mentioned here show that the Japanese had hardly flooded the market with convertibles, the best-selling models having gone out of production in the late 1960s.

Ultimately, the American authorities didn’t pass the regulations outlawing the soft-top, but even though the convertible’s future seemed assured, surprisingly few manufacturers took the opportunity to build one. The consensus of opinion seemed to be that the convertible market had simply ceased to exist after 1970. Maybe Mazda was right to explore the possibilities, and, by using the OGG route, the company didn’t have to commit itself fully until totally satisfied there was still sufficient interest. Although the LWS project was not guaranteed production status at this stage, the team at MANA was convinced it would eventually find its way into the showrooms.

IAD

In September 1984, International Automotive Design, better-known as IAD, was asked by Mazda to become involved with the LWS project. Based in Worthing in the south of England, IAD was founded by the late John Shute (an ex-GM body engineer and avid collector of MGs) in the early 1970s. Shute was well-known in the trade, and IAD soon gained an excellent reputation for developing prototypes.

Mazda wanted its new car to have a British flavour and actually commissioned IAD not only to build a running prototype based on the Duo 101, but also to carry out evaluations on a number of British classics. Cars – including the first Lotus Elan – were tested at the MIRA facility in the centre of England and reports compiled.

A fibreglass lookalike open body and makeshift interior were constructed around mechanical components from a selection of Mazda models: the 1.4 litre engine and transmission came from a rwd Familia, the front suspension and wheels were taken from an early RX-7, and the rear suspension was from a Luce (929). The interesting part of the prototype was the use of a backbone chassis, designed and built in-house by IAD.

The completed IAD running prototype, built in glassfibre and featuring a backbone chassis. It was based on the first MANA clay – the second clay had the air intake removed at the front, relocated door handles and different rear lights.

A rear view of the V705. Note the exceptionally large rear screen area and the Toyota reference on the number plate – typical British humour.

Given the code number V705 by Mazda, the car – with its fibreglass body (a feature Kato had insisted on at this early stage), backbone chassis and FR layout – was, in effect, the Japanese equivalent of the original Lotus Elan. The V705 was fully-functional and, under the direction of Project Manager, Bill Livingstone, it was eventually completed in August 1985.

California dreamin’

The enthusiastic team at MANA had done little on the LWS project since it was handed over to IAD, but work had recently started again to enable some subtle design changes to the body, the eventual result being the S-2 clay. In the meantime, on 17 September 1985, Mazda staff from Japan and America met up in Worthing to view and drive the IAD prototype in England.

On the first day, the car was viewed in the IAD works, but on the second day the group, led by Masakatsu Kato, was taken to the Ministry of Defence test track not too far from IAD, where the V705 was compared on a high speed loop, a road course and a skidpan with a Fiat X1/9, a Toyota MR2, and the new Reliant Scimitar. Everyone was exceptionally happy with the vehicle. Mark Jordan wrote in his report that IAD “did an excellent job. After testing the car, it felt very pleasing ...”

The car was then scheduled to be shipped back to Japan, but, on the orders of Managing Director, Masataka Matsui, newly-appointed head of the Technical Research Centre, it was sent to the States instead. Matsui wanted to see the new machine in its natural environment, which made sense, but it was also very risky as the car could have been spotted by someone from the motoring journals. For this reason, somewhere that wasn’t too busy had to be chosen. After much deliberation, Santa Barbara seemed the ideal place.

In mid-October, Matsui arrived in California to see the new car in the setting it was designed for. MANA had assembled a small group of cars for comparison (an RX-7, a Triumph Spitfire, and a Honda convertible by the Straman concern), and took the V705 to Santa Barbara on a car transporter. Anyone remotely interested in cars immediately came to look at the new vehicle, which wasn’t exactly anonymous as it carried Californian plates borrowed from a local distributor.

Unfortunately, whilst out driving, the Mazda crew came across a number of journalists testing cars, and the registration plates quickly gave the game away. Bob Hall, being an ex-writer, explained the situation and somehow managed to get the motoring scribes to agree not to publish any photographs.

In retrospect, Fukuda thought it was a mistake to expose the car so early. Overall, though, it was a highly successful day. Matsui was more than happy with the public response at this impromptu clinic. At dinner with the MANA team that evening, Matsui was convinced that the LWS had potential and declared “I think we should build this car.” More importantly, when he returned to Hiroshima, he gave the LWS project his full recommendation.

When the IAD-built V705 prototype arrived in America for its Santa Barbara excursion, the RX-7 wheels were changed for some multi-spoke items that would not give a clue to the car’s true identity. Arriving on the back of a car transporter wrapped in a grey cover, the vehicle was made ready for its drive around the local area, but its number plates from a Mazda distributor soon gave the game away.

Virtual reality

1985 saw the introduction of the all-new fwd Mazda Familia (323) series in Japan, and the second generation Savanna RX-7. The RX-7 was duly named 1986 ‘Import Car of the Year’ by Motor Trend magazine.

A number of interesting concept cars appeared as well. Suzuki displayed its R/S1 LWS at the 1985 Tokyo Show. However, somewhat surprisingly, despite favourable reactions, the vehicle never made it into production, so the way was still clear for Mazda. The Hiroshima marque displayed the MX-03, a four-wheel drive, four-wheel steer coupé designed by Kato, at the same event. With 2+2 seating, it was sportier than the MX-02 from two years earlier (which was quite staid by comparison), but was destined to remain a prototype.

Shigenori Fukuda returned to Japan to take up the post of General Manager of the Design Division. Having been closely involved with the LWS project from its birth, Fukuda was obviously keen to see it through to the end, as it was the epitome of his ‘Romantic Engineering’ concept. However, the LWS was still not guaranteed a place in the Mazda line-up. At the end of the 1980s, Fukuda stated that “the project was interrupted several times.” In fact, Shunji Tanaka feels that had Fukuda not returned to Japan, the LWS might never have seen the light of day.

There were a number of reasons for having doubts about the LWS’s future. Mazda had already approved its new MPV which, with the benefit of hindsight, was an excellent move (Japan’s roads are full of these utility vehicles nowadays), but was also pushing for a new model in the Light (or Kei) class. The tiny K-car was a proven winner, and, with limited resources available, many in the company recommended that this route should be taken and the LWS project suspended.

Fortunately, this immediate problem was overcome via a joint engineering agreement with Suzuki in relation to the Light Car; Mazda now had the resources to enable it to do the MPV, the K-car (the Carol) and the LWS, but the men in the finance department were still not too happy. America was always going to be the main market for an open sports car, and the value of the yen was making life hard for Japanese exports.

The first major Japanese sports car success in the US market, the Datsun 240Z, hit the shores of America in 1970. The floating exchange rate system was introduced in 1971, and almost immediately the yen began to strengthen against the dollar. By 1972, 300 yen would buy a dollar instead of the 357 needed at the start of the previous year.

With the oil crisis of 1973, the yen was quoted at 253 per dollar before the greenback recovered dramatically. By the end of the 1970s, when Mazda’s RX-7 arrived on the scene, the rate had dropped to below 200 yen to the dollar, and was still moving in the same direction. 1985 had seen the yen moving strongly against the dollar, pushing prices in export markets up to unprecedented levels, which had an obvious effect on sales.

This was not such an easy problem to resolve, as the thinking behind the LWS was that it should be cheap enough to tempt people into buying what was, at the end of the day, something of an indulgence.

In January 1985, AutoAlliance International Inc., a 50/50 venture with Ford, was established in Flat Rock, Michigan. Having a manufacturing plant in the States would overcome currency fluctuations (MX-6 production began in September 1987, followed shortly by the Ford Probe, and later the 626), but there were no plans to build the LWS there.

With initial sales projections pointing towards 1800 units a year for Japan, 30,000 for North America and around 3600 for Europe, the volume was hardly massive. Careful design, to keep production costs down, would ultimately be the car’s saviour (although, luckily, these figures proved grossly underestimated).

In the meantime, progress was slow. MANA eventually completed the S-2 clay in December 1985. When it was officially presented to the Board the following month, Yamamoto was fully behind the LWS idea, saying it had “a smell of culture.” Mazda’s Managing Director, Takashi Kuroda, also expressed his support, and, for this reason, on 18 January 1986, the P729 was grudgingly given approval. But then there was another, unexpected delay ...

Kato, who had overseen the project since inception, decided to step down from his position as head of P729 and concentrate his efforts on new ideas within the recently opened Technical Research Centre. Naturally, this meant a replacement had to be found. Fortunately, Toshihiko Hirai, previously in charge of the Familia (323), made it known that he would like to be considered for the LWS project. Born in 1935, Hirai was well-respected and had a proven record with the successful 323 range. With his vast engineering experience and a spell in the Service Department, he was declared the ideal man for the job and, in February, duly took up his new post as the P729’s Chief Engineer.

In the same month, MANA was told it could start on the third and final clay model (the S-3). Work began in earnest in the middle of March, with Tom Matano and Koichi Hayashi responsible for the majority of input, ably supported by Mark Jordan and Wu-Huang Chin.

The third and final clay produced by MANA. The front indicators were a little too large, and the shape of the air intake and tail graphics were further refined in Japan.

Toshihiko Hirai, the MX-5’s Chief Engineer, pictured by the author during a recent trip to Hiroshima. He is now a highly successful university lecturer.

Matano wanted to develop a family resemblance between the “faces” of the various cars in the Mazda range – a frontal view that would immediately single out the vehicle as a Mazda. Using BMW and Mercedes-Benz grilles as examples, he went on: “To us, this is a graphical way of identifying the car. It’s great if you have a [long] heritage, and so forth, that establishes you in such a way, but at this point in Mazda’s development we wanted to upgrade our image ... To achieve that, we wanted to have something like a body language to [distinguish] the Mazda for that time.

“I always look for the movement of the highlights on a car. It’s almost like a drama, or a symphony in some cases; like a Jaguar is a symphony. Every moment that lights move on a surface by driving [along], really [tells] the whole story of a car.”

Matano dislikes the use of fussy lines and heavy creases in styling. He said: “I often think of water, dropping onto the roof, following the curvature, going down the roof to the pillar, to the bottom of the pillar, to whatever. And every time this water has to think which way shall I go down – if the water has to think that way – the design is not right yet. You know, it’s not natural yet.

“Because it’s a convertible, the rear end is very important to identify the car. And yet we don’t really want to have a spoiler just for the sake of it, so it’s there but it’s not really obvious.”

During May, the project was considered advanced enough to call a joint meeting between the MANA staff and a large delegation from Japan. As far as the American team was concerned, the project was finished.

An interview with Shunji Tanaka (Chief Designer on the M1 body)

Mr Tanaka: “Today, there are many open two-seater cars on the market. However, in 1986, there was nothing resembling the open two-seater concept available, and it was hard even to carry out market research effectively. I remember that at the time we really struggled to get this car into production.”

Miho Long: “Could you tell us your favourite parts of the design, and why?”

Mr Tanaka: “I like the rear view when the car is open – I believe the rear view of a sports car has to be cute! I would also suggest the tail lamps, which are as one with the body. I wanted them to resemble a fundo [a balance weight from old-style weighing scales], so I shaved a tail lamp housing myself to get exactly the shape I desired.”

Miho Long: “Which would you say was the hardest part of the body design to execute?”

Mr Tanaka: “To create the authentic originality of Mazda and Japan on the body surface. You will notice that the lines enclose an aesthetic consciousness, giving different feelings depending on the angle from which the car is viewed, just like a Noh mask.“Every time I take up a chisel to create a Noh mask, I always respect the traditional simplicity and perfect curves which have been handed down over the centuries. Many different feelings and wishes are held within the mask, their appearance depending on the light and changing shadows. It is very characteristic of the Japanese, and completely different from the Western notion of expressing perfection concretely.

“I also wanted to enclose the rhythms – peace, motion, and silence – which exist in the Japanese heart, into the form of the sports car. For peace, I looked towards a statue of the Goddess of Mercy for inspiration, a truly graceful symbol. For motion, I thought of a wild animal when it’s hunting, running fast and accurate, and for silence, the tranquility of nature. I wanted the car to melt into the scenery, reflecting the light over its curved surfaces.

“I wanted to establish a new mould which was dynamic and original, yet distinctly Japanese in its origin – a mixture of sensitivity and modern technology.”

A return to Worthing

Once the decision was finally taken to embrace the lightweight sports car, Mazda again turned to IAD in England – this time to produce five complete running vehicles (engineering mules), and nine bodyshells for test and evaluation.

The mules didn’t have the PPF brace (all will be explained in due course), but otherwise were similar to the future production models. Significant detail changes were made along the way, including the use of a larger fuel tank (the original was far too small to be practical), and redesigning of the hood.

IAD actually carried out the front and rear crash tests, which the LWS passed with flying colours. After the Worthing phase in the proceedings was completed, a number of IAD staff were sent to Japan to personally explain problems encountered and make the transition as smooth as possible. The Mazda roadster was now a reality.

The synthesis of man and horse

The author’s point of view regarding sports cars has always been that they have only one main purpose – to be driven. Of course, some of the more exotic designs can be looked upon as works of art – like automotive sculpture – but basically speaking, a sports car is intended simply to provide driving pleasure.

The LWS project’s Chief Engineer, Toshihiko Hirai, felt exactly the same way. The Japanese love their cars; they represent personal space in a crowded city, something they can own. Few young people are in a position to buy anything in the housing market other than a tiny flat, as prices are extremely high. Even if somebody does take on a mortgage, repayments often continue well into the third generation of the family! The car is also a way to escape into the countryside, or a means of getting to the fishing port. In other words, even given the prospect of enormous traffic jams at certain times of the day, the automobile is considered a necessity to the enjoyment of life. However, a sports car is not just a means of transport: it has to look and feel special, and make its owner enjoy each and every mile, every corner, every gearchange.

Hirai gathered around him a team of about ten people, including Shinzo Kubo (who had been at MANA for a while, and would later become Hirai’s assistant), Kazuyuki Mitate and Hideaki Tanaka (both of whom had been with the project for some time), Takao Kijima and Masaaki Watanabe. Hirai, described by Bill Livingstone as “a very professional engineer,” began by listing every minute detail that he expected from a sports car, declaring he would not be happy until this criteria had been met. The list took on an almost legendary status once the journalists got to hear about it!

The concept was originally described as the synthesis of man and vehicle, but this was later changed to the synthesis of man and horse; Hirai wanted the new Mazda to give the driver the feeling of oneness that exists between a good rider and a thoroughbred stallion.

The final design

The third MANA clay (S-3), arrived in Hiroshima in July 1986, at a time when the studio was packed with other projects. A now familiar figure entered the story when Shunji Tanaka of Design Department No.1 (Hiroshima), took over as Chief Designer. Initially, Tanaka struggled to find a surface plate for the clay; considering the project had still not secured the full support of everyone at Mazda, in a country that is usually so organised, one wonders if this had not been planned to delay it still further. However, one was eventually obtained and, in November that year, Tanaka started work on the model.

Tanaka decided that the car was too heavy-looking for his liking. As he said, he proceeded to “take one layer of skin off the MANA model from front to rear” to reveal a lither profile. He insisted that the wheelbase be shortened slightly, causing more than a few problems for the layout engineers (MANA had already lengthened it during development of the third clay), the most obvious of which being the need to move the battery from behind the seats to a new location in the boot. The battery then encroached on luggage space, but the stylist stood by his decision. In the end, it helped with weight distribution anyway, so could be regarded as something of a mixed blessing, even though a special lightweight battery was eventually deemed necessary by Hirai.

Tanaka and Hirai had several more arguments during the development of the final model. Tanaka lowered the cowl height but was prevented by the Chief Engineer from going the extra 20mm (0.79in) he really wanted, although he did manage to change the width of the air intake. When Hirai found out after taking a ruler to the model, it was too late to change it!

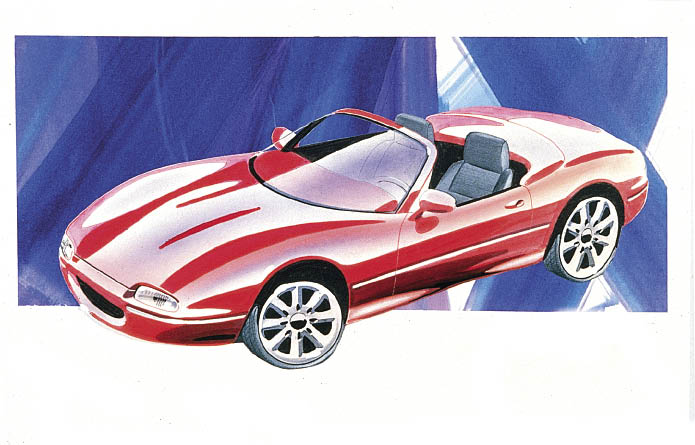

Once the project was moved to Hiroshima, another round of sketching began. Note the ‘LWS’ marking on the rear panel.

The MX-5 is definitely starting to show through in this proposal sketched by Iwao Koizumi (Chief Designer of the Atenza, or Mazda 6).

The LWS taking shape in Japan, based on MANA’s S-3 clay. The Americans had been worried that Tanaka would drop the pop-up headlights; in actual fact, Fukuda (seen pointing in the background) wanted the headlamps placed under clear covers, but regulations dictated that the pop-up arrangement remained. Note the Minilite-type wheels.