CHAPTER 7 Skeletal System: Gross Anatomy

217

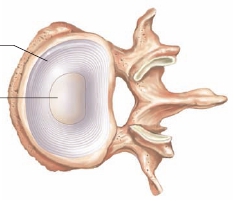

FIGURE 7.14

Surface View of the Back, Showing the Scapula

and Vertebral Spinous Processes

Annulusfibrosus

processes can be seen and felt as a series of lumps down the midlineof the back (figure 7.14). Much vertebral movement is accom-plished by the contraction of the skeletal muscles attached to thetransverse and spinous processes (see chapter 10).The location where two vertebrae meet forms the

intervertebral foramina

(table 7.9

d

; see figure 7.13). Eachintervertebral foramen is formed by

intervertebral notches

in thepedicles of adjacent vertebrae. These foramina are where spinalnerves exit the spinal cord.Movement and additional support of the vertebral column are madepossible by the vertebral processes. Each vertebra has two

superior

and two

inferior articular processes,

with the superior processesof one vertebra articulating with the inferior processes of the nextsuperior vertebra (table 7.9

c,d

). Overlap of these processes increasesthe rigidity of the vertebral column. The region of overlap and articu-lation between the superior and inferior articular processes creates asmooth

articular facet

(fas′et; little face) on each articular process.

Nucleuspulposus

(b)

Superior view

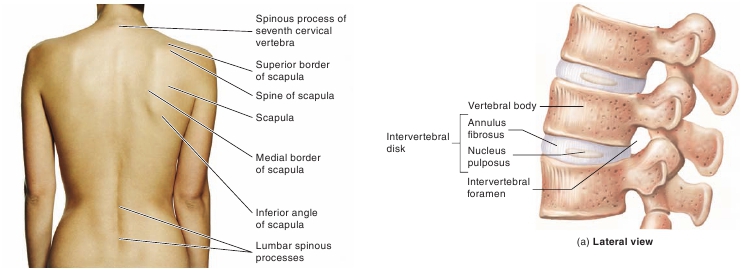

FIGURE 7.15

Intervertebral Disk

figure 7.13) have very small bodies; most have

bifid

(b ī ′fid; split)

spinous processes

and a

transverse foramen

in each transverseprocess through which the vertebral arteries extend toward thehead. Only cervical vertebrae have transverse foramina. Becausethe cervical vertebrae are rather delicate and have small bodies,dislocations and fractures are more common in this area than inother regions of the column.The first cervical vertebra is called the

atlas

(figure 7.16

a,b

)because it holds up the head, just as in classical mythology Atlasheld up the world. The atlas has no body and no spinous process,but it has large superior facets, where it articulates with the occipitalcondyles on the base of the skull. The joint between the occipitalcondyles and the atlas allows the head to move in a “yes” motionand to tilt from side to side. The second cervical vertebra is calledthe

axis

(figure 7.16

c,d

) because a considerable amount of rotationoccurs at the axis to produce a “no” motion of the head. The axishas a highly modified process on the superior side of its small bodycalled the

dens,

or

odontoid

( ō -don′toyd; tooth-shaped)

process.

The dens fits into the enlarged vertebral foramen of the atlas, andthe atlas rotates around this process. The spinous process of the sev-enth cervical vertebra, which is not bifid, is quite pronounced and

Intervertebral Disks

During life,

intervertebral disks

of fibrocartilage, which are locatedbetween the bodies of adjacent vertebrae (figure 7.15 and table 7.9;see figure 7.13), provide additional support and prevent the vertebralbodies from rubbing against each other. The intervertebral disksconsist of an external

annulus fibrosus

(an′ ū -l ŭ s f ī -br ō ′s ŭ s; fibrousring) and an internal, gelatinous

nucleus pulposus

(p ŭ l-p ō ′s ŭ s;pulp). The disk becomes more compressed with increasing age, sothe distance between vertebrae—and therefore the overall height ofthe individual—decreases. The annulus fibrosus also becomesweaker with age and more susceptible to herniation.

Regional Differences in Vertebrae

The vertebrae in each region of the vertebral column have spe-cific characteristics that tend to blend at the boundaries betweenregions (table 7.10). The

cervical vertebrae

(figure 7.16; see