Apart from metaphysics and physics proper, theology proved to be a most important factor in the formulation of physical theories of space from the time of Philo to the Newtonian era and even later. Because of the great effect of theological considerations upon the development of mechanics, as shown in the case of d’Alembert1 or of Maupertuis2 who derived from his theoretical physics a proof of the existence of God, it will be worth while looking into the matter. It may be objected to such an inquiry that a religious physicist would quite naturally insist, without recourse to tradition, upon linking science and religion. Yet it should be borne in mind that the general climate of opinion is historically conditioned.

Let us take for example Colin Maclaurin’s Account of Sir Isaac Newton’s philosophical discoveries, published in London in 1748 by Patrick Murdoch from the author’s manuscript papers. In Book One, Chapter One, we read: “But natural philosophy is subservient to purposes of a higher kind, and is chiefly to be valued as it lays a sure foundation for natural religion and moral philosophy; by leading us, in a satisfactory manner, to the knowledge of the Author and Governor of the Universe. To study nature is to search into his workmanship: every new discovery opens to us a new part of his scheme.” As this passage shows, the scientist’s attitude toward the very function of science may effect his work, while his mental disposition is generally to a great extent determined by his place in history and by his environment. As far as our problem is concerned, there is no doubt that a clearly recognizable and continuous religious tradition exerted a powerful influence on physical theories of space from the first to the eighteenth century.

This influence culminated in the assertion that space is but an attribute of God, or even identical with God. To Newton, absolute space is the sensorium of God; to More, it is divine extension. What are the sources of these doctrines and where did they originate? It is the purpose of this chapter to show that these sources can be traced back to Palestinian Judaism during the Alexandrian period. But this by itself is not enough; we have also to point out the possible channels through which this Eastern lore passed into Western thought.

The earliest indication of a connection between space and God lies in the use of the term “place” (ma om) as a name for God in Palestinian Judaism of the first century. “In Greek philosophy the use of the term ‘place’ as an appellation of God does not occur.”3 The only intimations of Greek influence in this usage are found in Sextus Empiricus and perhaps in Proclus.4 In Sextus Empiricus we read:

om) as a name for God in Palestinian Judaism of the first century. “In Greek philosophy the use of the term ‘place’ as an appellation of God does not occur.”3 The only intimations of Greek influence in this usage are found in Sextus Empiricus and perhaps in Proclus.4 In Sextus Empiricus we read:

And so far as regards these statements of the Peripatetics, it seems likely that the First God is the place of all things. For according to Aristotle the First God is the limit of Heaven. Either, then, God is something other than the Heavens limit, or God is just that limit. And if He is other than Heaven’s limit, something else will exist outside Heaven, and its limit will be the place of Heaven, and thus the Aristotelians will be granting that Heaven is contained in place; but this they will not tolerate, as they are opposed to both these notions, — both that anything exists outside of Heaven and that Heaven is contained in place. And if God is identical with Heaven’s limit, since Heavens limit is the place of all things within Heaven, God — according to Aristotle — will be the place of all things; and this, too, is itself a thing contrary to sense.5

With reference to these words Fabricius adds the following interesting remarks: “Deum Hebraei non dubitant, quia a nullo continetur, ipse vero immensa virtute sua continet omnia, appellare “ma om” sive locum, ut saepe fit in libello rituum Paschalium quern edidit Rittangelius.”6

om” sive locum, ut saepe fit in libello rituum Paschalium quern edidit Rittangelius.”6

We have quoted at length the passage from Sextus Empiricus in order to emphasize the fact that for Greek thought the association of God with space is, if admissible at all, only a very remote abstract deduction of an almost paradoxical character; while in Jewish theology of this period, and probably even earlier, the substitution of “place” for the name of God is a common procedure. It seems reasonable to assume that originally the term “place” was used only as an abbreviation for “holy place” (ma om

om  adosh), the place of the “Shekinah.” Incidentally, the Arabic term mak

adosh), the place of the “Shekinah.” Incidentally, the Arabic term mak m designates the place of a saint or of a holy tomb. Since theological conceptions in Judaism soon became more and more abstract and universal, the original connotation of the term “place” fell into oblivion and the word became an appellation of God without the implication of any spatial limitation. For the notion of God’s omnipresence very early became an important idea, as seen, for example, in the writings of the Hebrew Psalmist. Thus in Psalm 139 we read:

m designates the place of a saint or of a holy tomb. Since theological conceptions in Judaism soon became more and more abstract and universal, the original connotation of the term “place” fell into oblivion and the word became an appellation of God without the implication of any spatial limitation. For the notion of God’s omnipresence very early became an important idea, as seen, for example, in the writings of the Hebrew Psalmist. Thus in Psalm 139 we read:

Whither shall I go from they spirit? or whither shall I flee from thy presence?

If I ascend up into heaven, thou art there: if I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there.

If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea;

Even there shall thy hand lead me, and thy right hand shall hold me …

My substance was not hid from thee, when I was made in secret, and curiously wrought in the lowest parts of the earth.7

In the Midrash Rabbah we find the following discussion: “R. Huna said in R. Ammi’s name: Why is it that we give a changed name to the Holy One, blessed be He, and that we call Him ‘the place’? Because He is the place of the world. R. Jose b.  alafta said: We do not know whether God is the place of His world or whether His world is His place, but from the verse ‘Behold, there is a place with me’8 it follows that the Lord is the place of His world, but His world is not His place. R. Isaac said: It is written ‘The eternal God is a dwelling-place’;9 now we do not know whether the Holy One, blessed be He, is the dwelling-place of His world or whether His world is His dwelling-place. But from the text ‘Lord, Thou hast been our dwelling-place’10 it follows that the Lord is the dwelling-place of His world but His world is not His dwelling-place.”11

alafta said: We do not know whether God is the place of His world or whether His world is His place, but from the verse ‘Behold, there is a place with me’8 it follows that the Lord is the place of His world, but His world is not His place. R. Isaac said: It is written ‘The eternal God is a dwelling-place’;9 now we do not know whether the Holy One, blessed be He, is the dwelling-place of His world or whether His world is His dwelling-place. But from the text ‘Lord, Thou hast been our dwelling-place’10 it follows that the Lord is the dwelling-place of His world but His world is not His dwelling-place.”11

The Mishna could also be cited as illustrating the frequent use of the term “place” to denote God.12 It has been maintained that this use of the term is of Persian origin, but according to Wolfson13 it is undoubtedly of native Jewish origin. Elisaeus Landau14 referred to certain Pahlavi texts and to the much earlier Zend Avesta in which space is deified and reverenced, as mentioned also by Damascius. Landau traces the use of the term “place” or “space” as an appellation of God back to Simon b. Shetah who, according to Jerus. Berachoth15 had frequent contact with Persians. But Marmorstein16 has shown that the use of “space” in this sense dates back before Simon b. Shetah, at least to Simon the Just (c. 300 B.C.), which disproves Landau’s theory of Persian influence; and Geiger17 disposes of a possible Alexandrian origin.

The Jewish Palestinian metonymy is not to be taken simply as a metaphor, but is evidently the result of a long process of theological thought which culminated in the concept of the Divine Omnipresence. And if this is so, it provides additional support for the assumption of Palestinian origin. For such an ideological development is congenial only to a monotheistic religion and is alien to any form of polytheism whatever. Thus Schechter notes the various steps in the gradual widening of the Divine abode in Jewish theology: “Say the Rabbis, ‘Moses made Him fill all the space of the Universe, as it is said “The Lord he is God in the heaven above, and upon the earth beneath; there is none else,”18 which means that even the empty space is full of God.”19

In the Palestinian Talmud we find an interesting legend that admirably illustrates our thesis: R. Tanhuma narrates how a horrible storm threatened a boat on which a company of pagans and one Jewish boy were sailing; as their life seemed to be in danger, each passenger reached for his idol to worship it, but without success; finally the Jew yielded to the pagans’ request and prayed to his God, whereupon the sea calmed down. When they came to the nearest port, all of them went ashore to buy provisions, except the Jew. When asked why he stayed aboard, he replied, “What can a needy stranger like me do?” Whereupon they answered, “You a poor stranger? We are the strangers. We are here, but our gods are in Babylon or Rome; and others amongst us who carry their gods with them derive not the least benefit from them. But you, wherever you go, your God is with you.”20

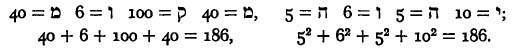

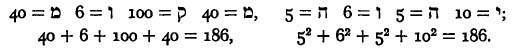

This notion, that God was at one and the same time here and there, had no pantheistic consequences in Jewish theology, but led to the association of God and space as an expression of his ubiquity. This usage had spread to Alexandrian philosophy,21 was incorporated in the Septuaginta22 and was adopted also in the pre-Mohammedan world of thought, as we see from the Divan of Lebid.23 In later Jewish literature the term “space” or “place” as a name for God became so frequent that an explanation, if only post facto, appeared to be called for. Thus the gematria explains that both the name of God (the nomen ineffabile) and the word “place” lead to the same number: adding the squares of the numbers corresponding to the letters of the holy name one gets the sum of the numbers that correspond to the letters of the word “place”:

The designation “place” for God and the mystical conception of God as the space of the universe are frequently encountered in the post-Talmudic-Midrashic literature. The Zohar vindicates this use by saying that God is called “space” because He is the space of Himself.24 As is well known, the Zohar is a collection of treatises, texts, and extracts belonging to different periods, but with one common purpose: to reveal the hidden truth in the Pentateuch. Tradition claims that Simon b. Yohai, a sage of the second century and pupil of Rabbi Akiba, was the author of this book of mystical interpretation. According to the legend, he had spent many years in complete solitude, when he received sacred revelations from the prophet Elijah. It is said that the Zohar has been hidden for more than a thousand years in a cave in Galilee until it was discovered by Moses of Leon at the end of the thirteenth century. According to another version, Moses of Leon compiled the Zohar himself, using an Aramaic idiom to give it an air of antiquity. Whatever its source may be, it is a collection of ancient Jewish folklore and oral tradition that had a great influence, and not on Jewish thought alone. Italy especially, that shifting conglomeration of republics, states, and cities in the Renaissance, became a fruitful soil for Jewish esoteric teachings and, in particular, for the spread of cabalistic ideas. In the second half of the fifteenth century, when Greek scholars streamed westward after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, there were among them Jewish scholars who found a refuge in Italy, as we know from the case of Elijah del Medigo. In 1480 Elijah was called to the University of Padua, where he made the acquaintance of Giovanni della Mirandola, who invited him to Florence. Pico della Mirandola is generally considered as the first to introduce the cabala into Christianity. By the time of Mirandola’s death, in the year 1494, cabalistic ideas had already spread farther to the north. Henry Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim, who became a lifelong devotee of the cabala, delivered a lecture in 1509 at the University of Dôle on Reuchlin’s De verbo mirifico in which he preached the doctrine of the cabala and which led to a controversy with a Franciscan, who accused him of being a “Judaizing heretic.” The promulgation of the Zohar toward the end of the sixteenth century in Italy added new impetus to the spreading of cabalistic ideologies to the north, and the number of scholars interested in this rabbinical learning increased yearly.

One of the most erudite scholars of his time, John Rainoldes (1549–1607), president of Corpus Christi College in Oxford, made an extensive study of rabbinical lore. The German alchemist Michael Maier (born in Ruidsburg, Holstein, 1568), who became court physician to the Emperor Rudolph, visited England in 1615, where he very likely exerted great influence on Robert Fludd. Fludd was one of the early English Platonists whose importance for English theories of space and time in the sixteenth century cannot be overlooked. He taught “the immediate presence of God in all nature” and illustrated his ideas from Trismegistus. “God is the center of everything, whose circumference is nowhere to be found.” One of the major sources of Fludd’s rabbinical knowledge was probably Rainoldes’ Censura librorum apocryphorum Veteris Testamentis.25

But before we continue with the history of the English Christian Cabalists and Platonists and their influence on theories of space and time, let us return to Italy, where Campanella, a leading figure in the new Italian natural philosophy, was engaged in formulating a spiritualized conception of space.

If we bear in mind that both Newton’s and Locke’s theories of space originated in part, at least, in Gassendi’s natural philosophy and that Gassendi was in personal contact with Campanella,26 we are in a position to see that Campanella’s ideas about space are of no little importance for the history of later natural philosophy. As can be shown in detail by comparing the writings of Campanella, especially his astrological and metaphysical works, or his Medicinalium”27 with the writings of Paracelsus and of Agrippa of Nettesheim, the influence on Campanella of German mystical thought of the middle of the sixteenth century was very great. But, as we know, Paracelsus, and Agrippa much more, were ardent students of the Jewish cabala. It is no wonder, therefore, that Campanella’s ways of thinking show strong cabalistic tendencies. In his De occulta philosophia (liber I) Agrippa restates in the spirit of the cabala the doctrine of the realization of the Divine Thought through the creation of a hierarchy of worlds. With Campanella the hierarchy of five mutually enveloping and penetrating worlds comprises the mundus maihematicus seu spatium, the third realization after the mundus Archetypus and the mundus mentalis. In his Metaphysicarum rerum juxta propria dogmata28 Campanella characterizes this mathematical world or space as the “omnium divinitas substentas, portansque omnia verbo virtutis suae …” In words analogous to those of R. Huna,29 “The Lord is the dwelling-place of His world but His world is not His dwelling-place,” Campanella states that space is in God, but God is not limited by space, which is His “divina creatura.”30 The idea of the identification of space with at least an attribute of the Divine Being gains new impetus in the second book,31 where we read: “Spatium, entia locans invenio primum immortale, quia nulli est contrarium.” In Campanella’s conception, space becomes an absolute, almost spiritual entity, characterized by divine attributes. Its reality guarantees a sound foundation for mathematical speculations, which, according to Campanella, ought to be based not on hypothetical artifacts but on reliable sense data.

Together with this cabalistic-Platonic conception we find in Campanella’s theory of space the strong influence of his teacher Bernardino Telesio. We shall have occasion in the next chapter to speak of Telesio since his doctrine represents a turning point in the history of physical thought of the sixteenth century owing to its anti-Aristotelian conception of space and time. But in the frame of the present chapter we are concerned only with the change brought about in Campanella’s original conception of space by Telesio’s critique. Campanella, too, came to the conclusion that space was completely homogeneous and undifferentiated, immovable and incorporeal, penetrated by matter and penetrating matter, destined for the collocation of mobile entities. “Up” and “down,” “right” and “left” were only pure creations of the intellect, designed to facilitate practical orientation among the multitude of concrete bodies, but with no real directional differentiations in space corresponding to them. Campanella is here following in the footsteps of his master, as he generally did, and to such an extent that he was held to be the reincarnation of him: “… horum clarissimus erat Thomas Campanella Stylensis, cujus in corpus Telesii ingenium transmigrasse dicebatur.”32

Another trend in the history of the theory of space, very similar in its mystical-theological character and its association of God and space, was the identification of space and light. From prehistoric times light was the symbol of supernatural forces. The oldest religions are of astral character, as Egypt’s Re and ancient Persia’s Ahura Mazda bear witness. In the Sutran33 Brahman is personified as the Primordial Light. Atman is honored by the Gods “as immortal life, as the light of lights.”34

Even the Bible, which prohibits all images of God, still uses the element of light as the medium in which God becomes visible to man: God appeared to Moses in a burning bush;35 a column of fire showed the children of Israel the way out of Egypt.36 We read in the Psalms: “Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment.”37 In the New Testament God is explicitly identified with light: “Ego sum lux mundi.”38 Light plays an important role in the metaphysical systems of Philo and of Plotin. In the vocabulary of the Jewish Midrashim and of the cabala “light” is one of the most important terms signifying the most holy conception. The word Zohar,39 the title of the most important book in Jewish mysticism, denotes “light,” “splendor,” or “glimmer.” According to the cabala, the Infinite Holy One, whose light originally occupied the whole universe, withdrew his light and concentrated it on his own substance, thereby creating empty space.40

This apotheosis of light became a fundamental characteristic of later Neoplatonism and medieval mysticism. Even the more sober natural philosophy of the Middle Ages, though still anthropomorphic with its hierarchy of values in nature, accepted light as the most “noble” entity in the world. Plotinus set the example of ranking light as highest in existence. Through its various degrees and emanations the macrocosm formed one coherent and organic unit. Light is the means by which universal order is maintained. In its purest actuality light is Deity. According to Saint Bonaventure, God is “spiritualis lux in omnia-moda actualitate.”41 The theories that identify space with light under the influence of Neoplatonism and religious mysticism are therefore essentially theological in character. In our treatment of them here we shall confine ourselves in the main to two representative examples, one in antiquity, the other in the thirteenth century. The first is the theory of Proclus; the second is that of Witelo.

Fragment No. 6 of The fragments that remain of the lost writings of Proclus42 discusses space as being the interval between the boundaries of the surrounding body. This is similar to the Stoic definition. But Proclus draws the conclusion that space must therefore be commensurable with things that are corporeal and since it is able to contain other bodies it must be in some sense corporeal in itself. Yet space must be immaterial and immovable; for were it material, it would not be able to occupy the same place as another body, and were it movable, it would be moving in space, that is, in itself. To Proclus, space contains the whole material world, but is not contained by the world and becomes therefore coextensive with the domain of light.43 It is regrettable that Proclus’s work On space, mentioned in various texts,44 is not extant; thus we know very little about the immediate source of this identification of space and light. Perhaps it was an old Pythagorean theory about the primitive light or the more poetical variation in Plato’s Republic where the myth of the Pampylian Er, son of Armenios, is related: “For this light binds the sky together, like the hawser that strengthens a trireme, and thus holds together the whole revolving universe.”45

The conceptions of the Neoplatonic “light-metaphysics,” propagated persistently also by Jewish philosophy and mysticism (Saadya of Fayum, Ibn Gabirol and many cabalists), exerted a strong influence on Robert Grosseteste. Assuming light (lux) as the first corporeal form and the first principle of motion, Grosseteste reduced the creation of the universe in space to the “auto-diffusion” of light. Light, which in his view is propagated by itself instantaneously, as shown by its physical manifestation, the visible light, is conceived by him as the basis of extension in space. As A. C. Crombie rightly points out in his book on Grosseteste,46 it was this fundamental assumption that made Grosseteste believe that the key to the understanding of the universe lies in the study of geometric optics. Thus, in the last analysis, it was the Neo-Platonic conception of space that led to the great interest in optics and mathematics exhibited by the thirteenth century.

Among the most conspicuous figures in this respect were the unknown author of the Liber de intelligentiis and the Silesian Witelo, both of whom were certainly influenced by Grosseteste.47 In fact, the writings of these two are so similar both in contents and in style that Clemens Baeumker erroneously attributed the Liber de intelligentiis to Witelo.48 As with Proclus, the point of departure in the unknown author’s theory is Aristotle’s physics. We read at the very beginning of the Liber de intelligentiis that space is the “ultimum continentis immobilis,” in contrast to Aristotle’s “ultimum immobile continentis.” As Baeumker remarks, the author accepted the introduction of two additional celestial spheres, the second of which is immovable, the motive being to bring science into line with Scripture.49 But when the author comes to the famous passage in Aristotle’s Physics reading, “Moreover the trends of the physical elements (fire, earth, and the rest) show not only that locality or place is a reality but also that it exerts an active influence,”50 he becomes Platonic in his conception of “dynamis” (power, in the sense of exertion of force) and interprets it as the faculty of space. In his view, the nature of space is characterized by two functions: to inclose (the periechein of Aristotle) and to support “continere” and “conservare.” Light, the source of all existence, the all-pervading power, ranking highest in the hierarchy of Being, light alone fulfills these two conditions. Hence space and light are one.

The assertion, “Unumquodque primum corporum est locus et forma inferiori sub ipso per naturam lucis,”51 is proved by a series of syllogisms.52

These writers were not the last proponents of the importance of light for a theory of space. Light played an important role in most cosmologies of the Italian natural philosophers of the Renaissance. Francesco Patrizi, the predecessor of Campanella, was also fascinated by the mysteries of light and made light an integral part in his speculations. He was faced, like most philosophers of nature, in the sixteenth century, with the formidable task of incorporating the inherited supernatural world of the Middle Ages in the newly discovered world of nature of the Renaissance. The problem was how to unite the corporeal concrete world of nature with the incorporeal world of spirit. Space, light, and soul, and the Neoplatonic doctrine of emanations, together constitute the means by which he tried to solve the problem. Space, the entity that is neither corporeal nor immaterial, serves as the intermediary between the two worlds. Indeed, it was created by God for the fulfillment of this function. Space is infinite, for an infinite cause can give rise only to an infinite effect. The traditional scholastic principle, according to which the effect is always feebler than the cause, applies, according to Patrizi, only to finite entities. The first thing to fill this space is light, the all-pervading, all-preserving medium of three dimensions, whose importance is not confined to its physical function as a transmitter of heat, power, and other influences; it is also metaphysically the way to God.

An outstanding example of a strong religious bias in the conception of space is the theory of Henry More.53 In order to substantiate his vigorous religious beliefs, More thought it necessary to augment the science of Descartes with cabalistic and Platonic concepts. That the cabala, apart from Neo-Platonic philosophy, was a major factor in More’s conception of space can be proved not only by an analysis of the conception itself, but on historical grounds as well. First of all, we know that More, together with Fludd, was regarded as one of the greatest rabbinical students of his time. He certainly studied Hebrew and read the Scripture in its original version, as may be seen from his wide use of that language in his various writings, especially in his Discourses on several texts of Scripture.54 Having studied the writings of Marsilius Ficinus, Plotinus, and Trismegistus, he was persuaded that cabalistic philosophy, as expounded, for instance, in the Liber drushim (Book of dissertations) of Isaac Luria, was of the greatest importance. As far as his theory of space is concerned, More himself refers to the cabalistic doctrine as explained by Cornelius Agrippa in his De occulta philosophia,55 where space is specified as one of the attributes of God.

More’s metaphysical writings are in the main a somewhat desultory expansion of his fundamental views on the nature of incorporeal substances, whose existence he was convinced that he had proved on the basis of his cabalistic studies. During the last twenty years of his life he wrote numerous publications on mystical subjects, including a Cabalistic catechism.56 Some of these writings were addressed to Baron Knorr von Rosenroth and published in the Kabbala denudata,57 a translation into Latin of cabalistic writings that has done an immense service to many occultists by furnishing material for their reveries.58

More exerted a great influence on Locke, Newton, and Clarke, and through them on eighteenth-century philosophy in general, so that his doctrine is worth analyzing in detail. His writings reveal that the problem of space occupied his mind as early as 1648 at least and continued to interest him till 1684; that is, his interest dates from his correspondence with Descartes to his correspondence with John Norris. In his letters to Descartes More places himself in strong opposition both to ancient Greek atomism and to the Cartesian identification of space and matter. Both seem to him to lead inevitably to materialism and atheism, and for the refutation of these he deems it necessary to demonstrate the existence of a spiritual Being, which permeates and acts in nature. To Descartes the attribute that distinguishes spirit from matter is thought, as manifested in contemplation and consciousness; to More it is spontaneous activity, the source of all change and motion. Since change and motion are present in all realms of nature, the question arises how this interaction can be performed on matter at all. The answer lies, according to More, in the nature of space, the clear understanding of which can alone save philosophy from an otherwise inevitable atheism. “Atque ita per earn ipsam januam per quam Philosophia Cartesiana Deum videtur velle e Mundo excludere, ego, e contra, eum introducere rursus enitor et contendo.”59

The chief motive behind More’s concern with the problem of space, as it is the motive of his whole philosophy, is to find a convincing demonstration of the indubitable reality of God, spirit, and soul. In accord with this purpose he rejects Descartes’ absolute identification of matter and extension. In order to prove the reality of spirit, it suffices to show that extension is spiritual provided extension itself is real. On the basis of this reasoning More’s treatment of the space problem may be divided into three parts: (1) extension is not the distinguishing attribute of matter; (2) space is real, having real attributes; (3) space is of divine character. We shall comment on each of these in turn.

(1) In his correspondence with Descartes More points out that, apart from the primary qualities of matter, mentioned by Descartes, matter has also the property of impenetrability or “solidity,” as impenetrability was called at that time. Impenetrability (and the related tangibility) is the criterium differentionis between matter and extension. As is well known, Locke in his Essay concerning human understanding60 takes account of these ideas. In order to understand the mutual interaction between the world of spirit and the world of matter it is necessary to find a common ground between them. This common ground is space. Hence it follows that extension characterizes the world of spirit no less than the world of matter. In a word, extension is not a distinguishing attribute of matter, but belongs to both spirit and matter.

(2) In order to prove that space is real, More used different arguments at different times. Already in his correspondence with Descartes he undertakes to refute the latter’s plenum against the existence of space as such. To both thinkers empty space does not exist; but if space may be empty as far as matter is concerned, it is yet, according to More’s view, always filled with spirit. Descartes contended that the walls of a vessel that is exhausted of air must necessarily collapse. “Si quaeratur, quid fiet, si Deus auferat omne corpus quod in aliquo vase continetur, et nullum aliud in ablati locum venire permittat? Respondendum est: Vasis latera sibi invicem hoc ipso fore contigua.”61 Descartes’ prediction of this presumably too complicated experiment, which in his view only a God is able to perform, was based on his philosophy of space and matter. Descartes published his Principia in 1644. Only a few years later, or perhaps even at the same time,62 a simple burgomaster performed such an experiment. Sed vasis latera non fierunt contigua! When reading today Descartes’ argumentation on this subject one has to bear in mind that the concept of “a sea of air,” surrounding the earth, evolved only toward the middle of the seventeenth century, as the history of pneumatics shows, and that it was unknown to the French philosopher.63 More’s reply to Descartes’ argument must be understood with these same cautions in mind: It is not necessary that the walls of the vessel collapse, since all motion of matter in Descartes’ own view is originated in God, so that God may impart to the walls of the vessel some counteracting motion and so prevent its collapse.64 Yet even if God can provide for the existence of an empty space, it still would not be an absolute vacuum because of the “divine extension” which permeates all space.

Still another proof for the reality of space, more scholastic in manner, is given in an appendix to More’s Antidote against atheism.65 The existence of space is guaranteed by its very measurability “par aunes ou par lieues.”66 In other words, space has indubitably the attribute of measurability, even when empty of all matter; as there are no accidents without substance, measurability as an accident demonstrates the substantiality of space. It is of course an incorporeal substance, since it includes “certain notions, such as immobility and penetrability, which are inconsistent with matter.”67 The penetrability of space affords in More’s view another proof of its incorporeality, and hence of its total discriminability from matter. More differs from Descartes, whose doctrine in this respect he characterizes in the following words: “For though it is wittily supported by him for a ground of more certain and mathematical after-deductions in his philosophy; yet it is not at all proved, that matter and extension are reciprocally the same, as well every extended thing matter as all matter extended. This is but an upstart conceit of the present age.”68

In the book just quoted, another very interesting demonstration of the reality of space is attempted, which, because of its originality and the probability of its direct influence upon Newton, calls for detailed treatment. Philotheus, the “zealous and sincere Lover of God and Christ, and of the whole Creation,” in his discourse with Hylobares, the “young, witty, and well-moralized Materialist,” gives the following example:

Philotheus: Shoot up an Arrow perpendicular from the Earth; the Arrow you know, will return to your foot again.

Hylobares: If the wind hinder not. But what does this Arrow aim at?

Philotheus: This Arrow has described only right Lines with its point, upwards and downwards in the Air; but yet, holding the motion of the Earth, it must also have described in some sense a circular or curvilinear line.

Hylobares: It must be so.

Philotheus: But if you be so impatient of the heat abroad, neither your body nor your phancy need step out of this cool Bowre. Consider the round Trencher that Glass stands upon; it is a kind of a short Cylinder, which you may easily imagine a foot longer, if you will.

Hylobares: Very easily, Philotheus.

Philotheus: And as easily phansy a Line drawn from the top of the Axis of that Cylinder to the Peripherie of the Basis.

Hylobares: Every jot as easily.

Philotheus: Now imagine this Cylinder turned round on its Axis. Does not the Line from the top of the Axis to the Peripherie of the Basis necessarily describe a Conicum in one Circumvolution?

Hylobares: It does so, Philotheus.

Philotheus: But it describes no such Figure in the wooden Cylinder itself: As the Arrow in the aiereal or material Aequinoctial Circle describes not any Line but a right one. In what therefore does the one describe, suppose, a circular Line, the other a Conicum?

Hylobares: As I live, Philotheus, I am struck as it were with Lightning from this surprizing consideration.

Philotheus: I hope, Hylobares, you are pierced with some measure of Illumination.

Hylobares: I am so.

Philotheus: And that you are convinced, that whether you live or no, that there ever was, is, and ever will be an immovable Extension distinct from that of movable Matter.69

In these last words, reminiscent of the style of Jewish medieval Piutim, Philotheus concludes with the absolute reality of space. It is interesting to note that in the case of the arrow, the proof is based, in the last analysis, on the relative motion of the earth according to the Copernican theory, and in the case of the rotating cylinder the proof is based on the assumption that rotation is always relative to something, a question that occupied Newton, as we know from his famous experiment with the rotating pail. Whereas in the first case no observable phenomena result, the second, according to Newton, makes the existence of absolute space physically demonstrable.

Space, then, is the medium in which the curved line or the cone is formed. But here the discussion is interrupted by Cuphophron, “a zealous, but Aiery-minded, Platonist and Cartesian, or Mechanist,” who contends, “that it may be reasonably suggested, that it is real Extension and Matter that are terms convertible; but that Extension wherein the Arrow-head describes a curvilinear Line is only imaginary.” This remark ushers in a line of arguments that for the modern reader suggests the Kantian conception of space. For Hylobares replies: “But it is so imaginary, that it cannot possibly be dis-imagined by humane understanding. Which methinks should be no small earnest that there is more than an imaginary Being there.”

Collateral confirmation of the reality of space is adduced by calling upon the authority of the ancient atomists, of Aristotle, and of the Pythagoreans with reference to the famous analogy that the “Vacuum were that to the Universe which the Air is to particular Animals.” Finally, More reverts to his old argument, which we characterized as scholastic, when he makes Hylobares say: “And lastly, O Cuphophron, unless you will flinch from the Dictates of your so highly-admired DesCartes, forasmuch as this Vacuum is extended, and measurable, and the like, it must be a Reality; because Non entis nulla est Affectio, according to the Reasonings of your beloved Master. From whence it seems evident that there is an extended Substance far more subtile than Body, that pervades the whole Matter of the Universe.”

(3) It is contended with regard to this “subtile” substance, called further on the “Divine Amplitude,” that it exists necessarily, and would exist even if all matter were annihilated. The necessary existence of space, even without matter, leads More to the final identification of space with God. For it might be argued, as Cuphophron argues toward the end of the discussion on the nature of space, that, if God as well as matter were annihilated from the world, extension would seem necessarily to remain. The spokesman for More’s reasoning here is Bathynous, “the deeply-thoughtful and profoundly-thinking Man,” who replies that God’s essence implies existence (the ontological proof). In other words, to assume the annihilation of God is a contradictio in adjecto. God and space have both the property of necessary existence; they are therefore one and the same.

This conclusion that God and space are one is drawn also in the appendix to the Antidote against atheism:

If after the removal of corporeal matter out of the world, there will be still space and distance, in which this very matter, while it was there, was also conceived to lie, and this distant space cannot but be conceived to be something, and yet not corporeal, because neither impenetrable nor tangible, it must of necessity be a substance incorporeal, necessarily and eternally existent of itself; which the clearer idea of a being absolutely perfect will more fully and punctually inform us to be the self-subsisting God.70

The attributes of space are attributes of God. A list of these attributes is given in More’s Enchiridion metaphysicum:

Neque enim Reale duntaxat, (quod ultimo loco notabimus) sed Divinum quiddam videbitur hoc Extensum infinitum ac immobile, (quod tarn certo in rerum natura deprehenditur) postquam Divina illa Nomina vel Titulos qui examussim ipsi congruunt enumeravimus, qui & ulteriorem fidem facient illud non posse esse nihil, utpote cui tot tamque praeclara Attributa competunt. Cujusmodi sunt quae sequuntur, quaeque Metaphysici Primo Enti speciatim attribunt. Ut Unum, Simplex, Immobile, Aeternum, Completum, Independens, A se existens, Per se subsistens, Incorruptibile, Necessarium, Immensum, Increatum, Incircumscriptum, Incomprehensibile, Omnipraesens, Incorporeum, Omnia permeans & complectans, Ens per Essentiam, Ens actu, Purus Actus. Non pauciores quam viginti Tituli sunt quibus insigniri solet Divinum Numen, qui infinito huic Loco interno, quem in rerum natura esse demonstravimus, aptissime conveniunt: ut omittam ipsam Divinum Numen apud Cabbalistes appellari “ma om,” id est, Locum.71

om,” id est, Locum.71

This list of attributes and names, a recurrent theme in the cabalistic writings, is quoted in full to show the extent to which More was influenced by Jewish mysticism. In his Divine dialogues as well More mentions the cabalists in connection with the divine nature of God. The discussion that we cited from the Dialogues ends with Psalm 90:

Lord, thou hast been our dwelling-place in all generations.

Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever thou hadst formed the Earth or the World, even from everlasting to everlasting, thou art God.

No doubt, the general tenor of the cabala may easily have provoked such spiritual ideas about space as were harbored by More. Anyone who has read the Book of formation (Sepher Yezirah), which deals with cosmogonical problems of the universe, or who has read on Luria’s cabalistic notion of the “Zimzum,”72 the divine self-concentration, creating space by self-restriction, will certainly accept the thesis that a somehow pantheistic interpretation of the cabala must necessarily lead to More’s conception of space.

Indeed, a similar intellectual process was most probably influential on the philosophy of Spinoza. With reference to his fundamental dictum; “Quidquid est, in Deo est et nihil sine Deo esse neque concipi potest,”73 Spinoza admits in a letter to Oldenburg: “… omnia, inquam, in Deo esse et in Deo moveri cum Paulo affirmo … et auderem etiam dicere, cum antiquis omnibus Hebraeis, quantum ex quibusdam traditionibus, tametsi multis modis adulteratis conjicere licet.”74 As A. Franck in La cabbale75 and much earlier (1699) Johann Wachter in Der Spinozismus in Jüdenthumb76 have shown, Spinoza’s remarks can refer only to cabalistic writings.

In contrast to More, Spinoza includes not only extension but also matter as an attribute of God, thus changing the conception of God into that of an absolutely impersonal, almost mechanical God, as is shown in his Ethics. Leibniz, who seems to have read Wachter’s De recondita Hebraeorum philosophia,77 in which the author repeats his thesis concerning Spinoza’s dependence on the cabala, wrote in this context in a letter to Bourget, “Verissimum est, Spinozam Cabbala Hebraeorum esse abusum.”78

This digression on Spinoza’s philosophy and its possible cabalistic sources has been inserted only to show that elements of Jewish esoteric writings, perhaps owing to the rise of Neo-platonic ideas, could have been easily integrated into the philosophy of the seventeenth century. We reserve judgment on the question how far in detail Spinoza, More, or any other thinker of that time has actually been influenced by the cabala, but we claim — as definitely demonstrated in the case of the concept of space — that certain general ideas of cabalistic origin have been absorbed into the intellectual climate of that period.

Our investigation into the influence of Judeo-Christian religious speculations on the conception of absolute space in the seventeenth century has not been presented as an uninterrupted chain of incontestable conclusions. Owing to the evasive character of the rather obscure and mystical ideas involved, the contention is rather based on the tradition of a certain “climate of opinion” or attitude of mind, and not on a direct communication of definite statements. In the case under discussion it was at least possible to expose all the major stages in this transmission.

More problematic, and still more conjectural, is the theory of a religious background in the rival conception of space, that is, Leibniz’s relational point of view. As we shall see in Chapter IV. Leibniz rejected Newton’s theory of an absolute space on the ground that space is nothing but a network of relations among coexisting things. In his correspondence with Clarke, Leibniz likens space to a system of genealogical lines, a “tree of genealogy,” or pedigree, in which a place is assigned to every person. The assumption of an absolute space, according to Leibniz’s view, is wholly analogous to a hypostatization of such a system of genealogical relations.

Now it is important to recall that a similar theory had already been propounded by the eleventh-century Muslim philosopher Al-Ghaz l

l , or possibly by one of his predecessors. Here again it becomes apparent that theological and metaphysical speculations were influential on the formulation of a theory of space. In fact, the whole issue in question is based on the ideological conflict between Aristotelian cosmology and the Koranic dogma of divine creation. For a full understanding of the situation it is perhaps most instructive to discuss both the temporal and the spatial aspect of the problem. Time was defined by Aristotle79 as the “number of motion” (for example, of the revolutions of the celestial spheres). Since without natural bodies there cannot be motion, Aristotle concluded that outside the finite heaven there is no time. Place, according to the Stagirite, presupposes the possibility of the presence of bodies.80 Since outside the finite heaven no body can exist, as proved in his writings previously, Aristotle deduced that outside the finite heaven there is no place. So far Muslim philosophy complies with Aristotelian cosmology. But now the conflict becomes apparent: whereas Aristotelian cosmology assumes the eternity of substance, the Koranic dogma affirms divine creation. Thus for Muslim philosophy a new problem is raised which did not exist for Aristotelian cosmology. It is the question whether there were space and time prior to the act of creation. Obviously, the answer must be negative, since space and time have no existence apart from matter per definitionem; they are mere relations among bodies. Space and time are consequently also products of creation. Muslim philosophy even went so far that it rejected the logical validity of the statement, “God was before the world was”81 (“K

, or possibly by one of his predecessors. Here again it becomes apparent that theological and metaphysical speculations were influential on the formulation of a theory of space. In fact, the whole issue in question is based on the ideological conflict between Aristotelian cosmology and the Koranic dogma of divine creation. For a full understanding of the situation it is perhaps most instructive to discuss both the temporal and the spatial aspect of the problem. Time was defined by Aristotle79 as the “number of motion” (for example, of the revolutions of the celestial spheres). Since without natural bodies there cannot be motion, Aristotle concluded that outside the finite heaven there is no time. Place, according to the Stagirite, presupposes the possibility of the presence of bodies.80 Since outside the finite heaven no body can exist, as proved in his writings previously, Aristotle deduced that outside the finite heaven there is no place. So far Muslim philosophy complies with Aristotelian cosmology. But now the conflict becomes apparent: whereas Aristotelian cosmology assumes the eternity of substance, the Koranic dogma affirms divine creation. Thus for Muslim philosophy a new problem is raised which did not exist for Aristotelian cosmology. It is the question whether there were space and time prior to the act of creation. Obviously, the answer must be negative, since space and time have no existence apart from matter per definitionem; they are mere relations among bodies. Space and time are consequently also products of creation. Muslim philosophy even went so far that it rejected the logical validity of the statement, “God was before the world was”81 (“K na all

na all hu wal

hu wal ‘

‘ lama”), if k

lama”), if k na is to be understood in a temporal sense. Even in the most fundamental proposition, “God created the world” (“halaka all

na is to be understood in a temporal sense. Even in the most fundamental proposition, “God created the world” (“halaka all hu al ‘

hu al ‘ lama”), the verb “created” (hala

lama”), the verb “created” (hala a) has to be understood in a causal and not in a temporal sense. The relation between God and the work of his hands is essentially a causal relation and not a relation in space and time. The question, “Where was God before the creation?” is meaningless, since space is a “pure relation” (i

a) has to be understood in a causal and not in a temporal sense. The relation between God and the work of his hands is essentially a causal relation and not a relation in space and time. The question, “Where was God before the creation?” is meaningless, since space is a “pure relation” (i

fat ma

fat ma

a) among created bodies.

a) among created bodies.

Theological polemics, as we see, led to a conception of space as a network of relations a conception that shows a striking resemblance to Leibniz’s idea about space. To be sure, it is always very difficult to assess any influence where thought processes are involved. Certainly, allowance has to be made for a complete independence between similar conceptions, especially if they are separated so much by time, space, and language. In the case under discussion it is certainly wise to defer judgment until a comparative study of the relevant texts establishes the fact of an indubitable intellectual dependence or until historic-biographic research proves the indebtedness without doubt. In our case it is rather tempting to suspect such a dependence if it is also noted that Leibniz’s monadology shows a striking resemblance to the atomistic theory and occasionalism of the Kal m, a famous Muslim school of thought, called also the “Muta-kallim

m, a famous Muslim school of thought, called also the “Muta-kallim n,” or “Loquentes,” as mentioned by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Details about their theory of space will be explained in Chapter III. As far as our question of theological influence on ideas about space is concerned, we have to stress the following fact: It has been established that the theory of atoms in Islam and the corresponding conception of space were originally of a purely profane character and became adapted to an extreme theistic dogma only during later stages of their development. From a strictly historical point of view it must be admitted, therefore, that the Kal

n,” or “Loquentes,” as mentioned by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Details about their theory of space will be explained in Chapter III. As far as our question of theological influence on ideas about space is concerned, we have to stress the following fact: It has been established that the theory of atoms in Islam and the corresponding conception of space were originally of a purely profane character and became adapted to an extreme theistic dogma only during later stages of their development. From a strictly historical point of view it must be admitted, therefore, that the Kal mic theory of space did not originate on the background of religious speculations. However, it was this background from which it drew, at the climax of its vitality, its emotional strength of conviction. Our exposition of the Kal

mic theory of space did not originate on the background of religious speculations. However, it was this background from which it drew, at the climax of its vitality, its emotional strength of conviction. Our exposition of the Kal mic conceptions of space, in Chapter III, refers to this later stage, the “orthodox” Kal

mic conceptions of space, in Chapter III, refers to this later stage, the “orthodox” Kal m, which once was defined as “the science of the foundations of the faith and the intellectual proofs in support of the theological verities.”82

m, which once was defined as “the science of the foundations of the faith and the intellectual proofs in support of the theological verities.”82

1 J. R. d’Alembert, Oeuvres philosophiques (Paris, 1805), vol. 2, Elémens de philosophie, chap. 6, p. 124.

2 P. L. M. de Maupertuis, Essai de cosmologie (Lyons, 1756).

3 H. A. Wolfson, Philo: Foundations of religious philosophy in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1947), vol. 1, p. 247.

4 E. Diehl, ed., Procli Diadochi in Platonis Timaeum commentarium (Leipzig, 1903–06), 117 d.

5 Sextus Empiricus, Adversus mathematicos (Against the physicists), II, 33, trans. by R. G. Bury (Loeb Classical Library; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1936), vol. 3, p. 227.

6 J. A. Fabricius, ed., Sexti Empirici opera (Leipzig, 1840–41), p. 681.

7 Ps. 139: 7–10, 15.

8 Exod. 33:21.

9 Deut. 33:27.

10 Ps. 90:1.

11 Midrash Rabbah, Genesis II, LXVIII, 9 (trans. by H. Freedman; Soncino Press, London, 1939), p. 620.

12 Aboth II, 9; Pessah X, 5; Middoth V, 4.

13 Wolfson, Philo, vol. 1, p. 247.

14 E. Landau, Die dem Raum entnommenen Synonyma für Gott (Zurich, 1888), p. 42.

15 Palestinian Talmud, Berachoth, VII, 2, Nasir V, 5.

16 A. Marmorstein, The old rabbinic doctrine of God (London, 1927), vol. 1, p. 92.

17 A. Geiger, Nachgelassene Schriften (Breslau, 1885), vol. 4, p. 424.

18 Deut. 4:39.

19 S. Schechter, Some aspects of rabbinic theology (New York, 1910), p. 25.

20 Berachoth, IX, Halacha 1.

21 See Philo, De somniis, I, 575.

22 Compare Exod. 24:10 with the Hebrew original.

23 J suf Dij

suf Dij -ad-D

-ad-D n al-Ch

n al-Ch lid

lid , ed., Der Diwan des Lebid (Vienna, 1880), p. 12.

, ed., Der Diwan des Lebid (Vienna, 1880), p. 12.

24 Zohar, I, 147 b; II, 63 b and 207 a.

25 Oppenheim, 1611.

26 They met, for example, in Aix. See Gassendi’s biography of Peiresc.

27 Thomas Campanella, Medicinalium juxta propria principia libri septem (Lyons, 1635).

28 Paris, 1638.

29 See p. 28.

30 Campanella, De sensu rerum et magia, libri quatuor (Frankfurt, 1620), I, c. 12.

31 Ibid., c. 26.

32 Erythraeus, Pinacotheca, I, p. 41.

33 Sutran, I, 3. 22–23.

34 B ih ad-ara

ih ad-ara yakam, 4, 4, 16; cf. P. Deussen, The system of the Ved

yakam, 4, 4, 16; cf. P. Deussen, The system of the Ved nta (Chicago, 1912), p. 130.

nta (Chicago, 1912), p. 130.

35 Exod. 3:4.

36 Exod. 13:21; Num. 14:14.

37 Ps. 104:2.

38 John 8:12.

39 The name is derived from Dan. 12:3.

40 The cosmogony of Genesis does not conceive space as a product of creation. But God’s first words were: “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). Thus light was created before the stars or the sun existed.

41 Liber sententiarum, II, 13 a. Cf. Etienne Gilson, La philosophie de Saint Bonaventura (Vrin, Paris, 1943), p. 217.

42 English translation by Thomas Taylor (London, 1825), p. 113.

43 Simplicius, Physics, 612, 32.

44 For example, in the Fihrist.

45 Plato, Republic, X, 616.

46 A. C. Crombie, Robert Grosseteste and the origins of experimental science (Clarendon, Oxford, 1953), p. 104.

47 A. Birkenmajer, “Études sur Witelo,” Bull. intern. acad. polon., Classe hist. philos. (Cracow), p. 4 (1918), p. 354 (1920), p. 6 (1922).

48 C. Baeumker, “Zur Frage nach Abfassungszeit und Verfasser des irrtümlich Witelo zugeschriebenen Liber de intelligentiis,” in Miscellanea Francesco Ehrle (Studi e testi, 37–47) (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City, 1924). The Liber de intelligentiis was edited with a commentary by Baeumker (Münster, 1908).

49 Cf. the “caelum Empyreum” of William of Auvergne.

50 Aristotle, Physics, 208 b 10–11.

51 Liber, de intelligentiis, VIII, 4. (See reference 48.)

52 “Cuius expositio est quod locus est ultimum continentis immobilis; illud autem ultimum caeli est ultimum per comparationem ad id ad quod determinatur locus unicuique inferiori sub ipso, sicut manifestum est de naui et palo fixo in aqua. mutat enim superficiem corporis continentis, scilicet aquae, non tamen mutat locum quia caeli non mutat partem, per comparationem ad quam determinabatur ei locus. unde caeli ultimum locus est. Hoc autem habet naturam lucis. Illud enim ultimum est continens et conseruans, cum sit locus …”

53 For his biography and intellectual development, see R. Ward, The life of Dr. H. More (London, 1710).

54 “By the late pious and learned Henry More, D. D.” (London, 1692).

55 III, 11. Cf. Friedrich Barth, Die Cabbala des H. C. Agrippa von Nettersheim (Stuttgart, 1855).

56 For a list of More’s cabalistic writings, see Gerhard Scholem, Bibliographia kabbalistica (Berlin, 1933), p. 110.

57 Kabbala denudata seu doctrina Hebraeorum transcendentalis et metaphysica (Sulzbach, 1677).

58 On the relations between More, Knorr, and Van Helmont, see John Tulloch, Rational theology and christian philosophy in England in the 17th century (Edinburgh and London, 1872), vol. 2, p. 345.

59 Henry More, Enchiridion metaphysicum sive de rebus incorporeis (London, 1671), part I, chap. 8, 7.

60 Book II, c. 4.

61 Descartes, Principia philosophiae, II, 18.

62 We do not know the exact date when Otto von Guericke began his famous line of experiments. It was between 1635 and 1654. In 1657 the first accounts of the air-pump experiments were published by Kaspar Schott in his Mechanica hydraulico-pneumatica, through which Robert Boyle became acquainted with Guericke’s experiments.

63 See J. B. Conant, On understanding science (Mentor, New York, 1952), p. 54.

64 Oeuvres de Descartes (Paris, 1824–1826), vol. 10, p. 184.

65 First edition published 1653 (appendix 1655, London).

66 Oeuvres de Descartes, vol. 10, p. 214.

67 More, Enchiridion metaphysicum, VI–VIII; letter to Descartes, March 1649.

68 More, Divine dialogues (London, 1668), I:XXIV.

69 Ibid. (London, ed. 2, 1713), p. 52.

70 A collection of several philosophical writings 6f Dr. Henry More (London, ed. 2, 1655), appendix, p. 338. Cf. F. I. MacKinnon, ed., Philosophical writings of Henry More (London and New York, 1925).

71 More, Enchiridion metaphysicum, part I, chap. 8.

72 “Deus creaturus mundos contraxit praesentiam suam,” Kabbala denudata (Sulzbach, 1677), part II, p. 150.

73 “Ethica more geometrico demonstrata,” I, prop. 15, in Spinoza, Opera (ed. C. Gebhart; Heidelberg, 1925), p. 56.

74 H. Ginsberg, ed., Der Briefwechsel des Spinoza im Urtext (Leipzig, 1876), p. 53, Epistola XXI; also Epistola LXXXIII.

75 Adolphe Franck, La cabbale ou la philosophie des Hébreux (Paris, 1843).

76 J. G. Wachter, Der Spinozismus in Jüdenthumb oder die von dem heutigen Jüdenthumb und dessen geheimen kabbala vergötterte Welt (Amsterdam, 1699).

77 Published in 1706.

78 Letter of the year 1707.

79 Aristotle, De caelo, I, 9, 279 a.

80 Ibid.

81 Algazel, Tahafot Al-Falasifat (ed. by Maurice Bouyges, S. J.; Beyrouth, 1927), p. 53.

82 Sir Thomas Arnold and Alfred Guillaume, The legacy of Islam (Oxford University Press, London, 1949), p. 265.

om) as a name for God in Palestinian Judaism of the first century. “In Greek philosophy the use of the term ‘place’ as an appellation of God does not occur.”3 The only intimations of Greek influence in this usage are found in Sextus Empiricus and perhaps in Proclus.4 In Sextus Empiricus we read:

om) as a name for God in Palestinian Judaism of the first century. “In Greek philosophy the use of the term ‘place’ as an appellation of God does not occur.”3 The only intimations of Greek influence in this usage are found in Sextus Empiricus and perhaps in Proclus.4 In Sextus Empiricus we read: m

m alafta said: We do not know whether God is the place of His world or whether His world is His place, but from the verse ‘Behold, there is a place with me’

alafta said: We do not know whether God is the place of His world or whether His world is His place, but from the verse ‘Behold, there is a place with me’

l

l , or possibly by one of his predecessors. Here again it becomes apparent that theological and metaphysical speculations were influential on the formulation of a theory of space. In fact, the whole issue in question is based on the ideological conflict between Aristotelian cosmology and the Koranic dogma of divine creation. For a full understanding of the situation it is perhaps most instructive to discuss both the temporal and the

, or possibly by one of his predecessors. Here again it becomes apparent that theological and metaphysical speculations were influential on the formulation of a theory of space. In fact, the whole issue in question is based on the ideological conflict between Aristotelian cosmology and the Koranic dogma of divine creation. For a full understanding of the situation it is perhaps most instructive to discuss both the temporal and the

n,” or “Loquentes,” as mentioned by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Details about their theory of space will be explained in Chapter III. As far as our question of theological influence on ideas about space is concerned, we have to stress the following fact: It has been established that the theory of atoms in Islam and the corresponding conception of space were originally of a purely profane character and became adapted to an extreme theistic dogma only during later stages of their development. From a strictly historical point of view it must be admitted, therefore, that the Kal

n,” or “Loquentes,” as mentioned by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Details about their theory of space will be explained in Chapter III. As far as our question of theological influence on ideas about space is concerned, we have to stress the following fact: It has been established that the theory of atoms in Islam and the corresponding conception of space were originally of a purely profane character and became adapted to an extreme theistic dogma only during later stages of their development. From a strictly historical point of view it must be admitted, therefore, that the Kal mic theory of space did not originate on the background of religious speculations. However, it was this background from which it drew, at the climax of its vitality, its emotional strength of conviction. Our exposition of the Kal

mic theory of space did not originate on the background of religious speculations. However, it was this background from which it drew, at the climax of its vitality, its emotional strength of conviction. Our exposition of the Kal suf Dij

suf Dij ih ad-ara

ih ad-ara yakam,

yakam,