1–27. In the time … when the sty is opened: This last canto of the Malebolge has perhaps the most elaborate opening, along with 24.1–21, and is a major instance of the featuring of Thebes and Troy in lower Hell (see the note to 26.52–54). Commentators have remarked on a disproportion between the atrocities in the myths and the actions of Gianni Schicchi and Myrrha. As a modem Florentine and an ancient Greek, they are correlated with Master Adam and Sinon (see the note to lines 100–129). The two are mentioned later as disseminators of news (lines 79–80).

1–12. In the time … her other burden: Juno, jealous of Semele (daughter of Cadmus, founder of Thebes), first destroys Semele (Met. 3.259–313); later, jealous of Semele’s son Bacchus, she has the Fury Tisiphonê” (see the note to 9.30–51) drive Athamas and his wife Ino (another daughter of Cadmus) mad (Met. 4.464–542). Dante sharply condenses Ovid’s account; he echoes particularly lines 512–19:

Protinus Aeolides media furibundus in aula clamât, Io, comités, his retia tendite silvis! hic modo cum gemina visa est mihi prole leaena, utque ferae sequitur vestigia coniugis amens: deque sinu matris ridentem et parva Learchum bracchia tendentem rapit et bis terque per auras more rotat fundae, rigidoque infantia saxo discutit ora ferox.

[Suddenly the son of Aeolus (Athamas), mad in the midst of the palace, cries, “Hurrah, comrades, spread the nets here in the woods! here just now I saw a lioness with twin cubs.” And he follows the footprints of his wife as if she were a beast, and from his mother’s bosom seizes Learchus, who is laughing and holding out his little arms, and whirls him in the air three, four times, like a sling, and shatters his infant face against the hard stone savagely.]

The theme of violence against children is central to Canto 33.

13–21. And when Fortune … twisted her mind: An even more condensed epitome of events from Met. 13.408–575, also taking place by the sea. After the fall of Troy (the Trojan Horse figures later in the canto), the former queen, Hecuba, is enslaved by the Greeks. Sailing home, the Greeks stop in Thrace; there Achilles’ ghost demands the sacrifice of Hecuba’s daughter Polyxena, over whom she utters a long lament. When she goes to the seashore for water to wash the body, she finds the body of her youngest, Polydorus, murdered by King Polymnestor (Dante drew on Vergil’s version of the Polydorus story in Canto 13). She kills Polymnestor by thrusting her fingers into his eyes, and when the Thracians hurl weapons and stones at her (lines 567–69):

… missum rauco cum murmure saxum morsibus insequitur rictuque in verba parato latravit conata loqui.

[… the hurled stone she pursues with a hoarse murmur, biting, and, when showing her teeth as if for words, she barked when she tried to speak.]

Like Ovid, Dante leaves implicit Hecuba’s metamorphosis into a dog (explicit in Euripides and Seneca); Athamas’s claws (line 9) also suggest a beast. The medieval commentators on Ovid identify madness (alienation of mind) as one of the forms of metamorphosis.

22–27. But neither . .. sty is opened: That is, the madness of Athamas and Hecuba was not so cruel as that of these two shades. The animal references have moved from lioness and cubs (line 8) to unspecified claws (line 9) to dog (line 20) to rabid pigs (cf. 13.112–13, in a context related to this one by the catalog of Sienese spendthrifts in 29.125–32).

32. That goblin is Gianni Schicchi: This new category of falsifiers, the impersonators, suffer from rabies. Bevenuto suggests the contrapasso: “as madness is an alienation of the mind, so they alienated theirs by assuming the person of another.” Gianni Schicchi is further identified in lines 42–45.

37–41. That is the ancient soul… another’s shape: The story of Myrrha, who became the mother of Adonis, is told in Met. 10.298–502. Line 39, “al padre, fuor del dritto amore, arnica” (cf. 5.103), makes contiguous the terms of the etymological figure (italicized), of which the second, arnica, is placed outside the preceding parenthetical phrase. Scellerata (line 37) echoes Ovid’s use of the term scelus [crime] to characterize Myrrha (Met. 10.314–15).

Jacoff (1988) points out most of the women shown in Hell have sinned sexually: Francesca (Canto 5), Thaïs (Canto 18), Myrrha (we may add Potiphar’s wife); the others are Manto and the diviners (Canto 20) (see the note to 18.133–35).

41, 44. counterfeiting herself in, counterfeit in himself: Note the antithetical symmetry of the two expressions, pointed out by Torraca; the point seems to be that both have equal validity: the impersonations wrong (“falsify”) both the impersonator and the one impersonated.

42–45. just as the other … legal form: Gianni Schicchi, who died around 1280, was a prominent member of the Cavalcanti family, famous as a mimic. No references to this story survive that antedate the Comedy. The early commentators relate that Simone Donati (the future father of Corso, Forese, and Piccarda) persuaded Gianni Schicchi to impersonate his dead uncle, Buoso Donati, and to dictate a will in Simone’s favor; Gianni willed to himself the “queen of the herd,” the most beautiful mare or mule in all Tuscany. Giacomo Puccini wrote a richly comic one-act opera on the story.

45. making a will … legal form: That is, before a notary and witnesses. Dante here condemns a violation of the legal norms that ensure the orderly transfer of property; compare the concern with the Sienese spendthrifts that concluded the last canto. The canto now reveals its major focus (see the note to lines 49–129).

49–129. I saw one … invited with many words: The major focus of the canto, and the conclusion of the Malebolge, focuses on two souls: Master Adam and Sinon. The debasing of currency (Master Adam debased the florin, the foundation of Florentine economic power) would be increasingly recognized, in the course of the fourteenth century—which saw a number of monetary crises—as a major economic problem affecting all of Europe (see Johnson 1956; Shoaf 1983). Sinon of Troy (introduced in line 98) is an instance of false testimony, like Gianni Schicchi, which in Sinon, Dante identifies as at the very root of Western history, the fall of Troy.

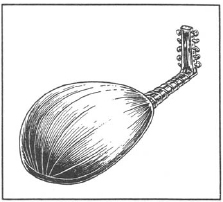

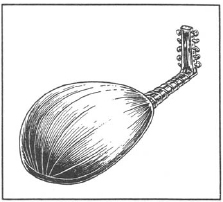

49–51. I saw one … the other forked part: That is, if one ignored the legs, the shape was that of a lute, which has an egg-shaped belly surmounted by a narrow neck (the fingerboard) that is bent back to accommodate the pegs for the strings (the metaphor thus implies that the soul is craning its neck; the lute is to be imagined with its flat face down [Figure 6]). Dante is drawing on the traditional notion of Christ on the Cross as being like a stringed instrument, his tendons stretched on the wood (Heilbronn 1983); this is a particularly rich instance of an infernal punishment parodying the Crucifixion (cf. the notes to 23.100–102, 118–20 and Additional Note 16). The drum of lines 102–3 would consist of skin stretched on a wood frame.

52–57. The heavy dropsy … the other upward: According to medieval medical writers, the type of dropsy from which Master Adam is suffering, timpanite [drum dropsy], bringing intense thirst, is caused by a malfunction of the liver, which normally converts the food, already “cooked” by the heat of the stomach and broken down into an intermediate liquid (omor, line 53), into blood, which the heart then distributes to the rest of the body; the malfunction creates impure humors that distend the belly while the other members, especially the face, lose flesh (the face “does not reply to”–is out of proportion with—the belly: the harmony, or tempering, of the fluids of the body is disrupted, so that the body is like a discordant musical instrument; see Spitzer 1963). As the commentators point out, these lines are characterized by unusual terms and harsh sounds, especially in rhyme: leuto [lute], ventraia [belly], dispaia [unpairs]–the last two apparently coinages of Dante’s (cf. discarno [lose flesh], line 69); all refer to the belly or lower body (cf. anguinaia [groin], forcuto [forked], lines 50–51).

57. turns one of them … the other upward: Thus the lips, too, are “unpaired” by the disease.

58–129. O you … with many words: The scene with Master Adam moves gradually from his learned, self-pitying effort to elicit sympathy to the futile exchange of malicious taunts and blows with Sinon. Uniquely among the souls of the other world, in this scene Master Adam entirely forgets his dialogue with the pilgrim. Master Adam’s fixation on revenge, and its role in his damnation, is similar to Ugolino’s. For Master Adam’s importance in the Malebolge as a whole, see Additional Note 13.

58–90. O you … three carats of dross: Master Adam’s first speech is eleven terzinas, thirty-three lines long. At its center, with ma [but], line 76 (to what does the “but” refer?), the focus becomes his hatred and desire for vengeance.

58–61. O you … to the wretchedness of Master Adam: These lines echo the famous passage in Lam. 1.12 (echoed by Dante also in Vita nuova 1 and in 28.130–32–Bertran de Born’s opening words; Lam. 1.1 is echoed in Vita nuova 29, 1.2 in Inf. 8.77), spoken by the personified Jerusalem after the destruction of the city in 586 B.C.:

O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite et videte si est dolor sicut dolor meus, quoniam vindemiavit me, ut locutus est Dominus in die irae furoris sui.

[O you all who pass by in the road, attend and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow, for the Lord has harvested me according to his word in the day of his anger

(trans. R. M. D.).]

Figurally the fall ofjerusalem, like the destruction of Sodom, looks forward to the Last Judgment; tropologically these lines were interpreted as expressing the fear of damnation. That Bertran de Bom and Master Adam quote the same biblical passage, one spoken by a personification of the body politic, itself points to the central theme of these cantos.

61. Master Adam: One Adam of England is identified in a legal document of 1277 as a “familiar” (that is, a member of the household) of the Conti Guidi of Romena; a chronicler relates that a representative of the Conti Guidi was burned in Florence in 1281 for circulating counterfeit coins.

62–63. alive, I had … drop of water: Dante is drawing on the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16.19–31): the rich man dies and, burning in Hell, sees in the bosom of Abraham (in Heaven) the beggar Lazarus, “full of sores” in life, whom he had spumed. He begs to have Lazarus dip the tip of a finger in water and bring it to him, and when Abraham replies that the gulf between Heaven and Hell is absolute, the rich man begs him to have Lazarus warn his five brothers; Abraham refuses, for “if they hear not Moses and the Prophets, neither will they believe, if one rise again from the dead.”

64–75. The litde streams … burned up there: The Casentino is a mountainous region east of Florence, including the upper basin of the Arno, in Dante’s time under the control of the Conti Guidi (see the note to 16.34–39), of whose casde at Romena the ruins still exist. The image of the streams intensifies Master Adam’s thirst at several metaphorical levels beyond the literal: they are an image of the health and innocence of the earth, contrasting sharply with Master Adam’s disease, and they imply the idea of baptism and its renewal of childlike innocence, present also in the other image referred to, that of the Baptist stamped on the florin. The supreme irony of the passage is that the very place where he sinned and the products of his sin, if Master Adam had attended to them, could have led him to repentance and salvation. Master Adam’s name, of course, is itself a reminder of the theological context; he should have remembered the biblical Adam when he was in the Edenic Casentino (on his offspring, see the notes to lines 79–90 and 118–20).

67. always stand before me: Dante has in mind the classical precedent for such torments, Tantalus (Met. 4.458–59): “tibi, Tantale, nullae/ deprenduntur aquae, quaeque inminet, effugit arbor” [no waters, Tantalus, can be caught by you, and the tree above you flees].

70–72. The rigid justice … the more to flight: In other words, God’s justice probes Adam internally by causing the image of the streams to be ever present to him; to dismiss it is beyond his power. Thus the true image of the streams torments the producer of false images (i.e., counterfeit coins).

72. to put my sighs the more to flight: To make him sigh (pant) more frequendy.

73–74. where I falsified the alloy sealed with the Baptist: In order to counterfeit florins, Master Adam had to imitate a distempered digestive system: first he cooked and refined gold, producing a liquid (parallel to the first digestion in the stomach); then he contaminated the gold by adding dross (parallel to the malfunction of the liver); finally, placing cast disks of the contaminated gold in a die or matrix, with blows of a hammer he imprinted on them the outer form of the florin—on one side, the Florentine lily, and on the other, the city’s patron saint (see 13.143–50, with notes), John the Baptist; this imprinting is parallel to the liver’s final production of blood (see Durling 1981a). The alloy of the florin is “sealed with the Baptist” to testify (cf. line 45) to the correct weight and composition of the coin. Master Adam’s term lega [alloy] also means “league” or “covenant”; both refer to the social bond that his crime violates (11.56) and are additional reminders of the Baptist’s call to repentance.

Medieval writers thought of money as the blood of the body politic; in their conception the heart was a reservoir, and blood flowed outward from the heart like a river (the idea of the circulation of blood is much later). Master Adam is an image of a distempered body politic (see 28.142, with note, and Additional Note 13).

76–90. But if I might see … three carats of dross: Like the first half of his speech, this half ends with the specification of his sin, this time even more precise. Italian battere [to strike, to mint] refers to the hammer blow on the matrix. The three carats of dross made Master Adam’s florins weigh twenty-one carats instead of twenty-four.

78. for Fonte Branda … trade the sight: Several candidates have been suggested for what must have been a famous spring. Master Adam’s hatred is so strong that he would prefer to witness his enemies’ suffering than to have his thirst relieved. This amounts to preferring vengeance to salvation.

80. if the raging shades … tell the truth: In other words, Gianni Schicchi and Myrrha—and presumably the other impersonators—are able to speak and disseminate information.

81. but what does it help … members are bound: Another “but,” whose referent is worth considering. The Italian che mi val means literally “what is it worth to me” (cf. coins) or “what power does it give me” (cf. 22.127). There is an important pun in legate [bound], from the same root as lega (see note to lines 73–74): his limbs are incapable of motion, made of a contaminated alloy, and bound by God’s judgment (in fact, he is a bondslave to the Old Law; he is the Pauline Old Man of Romans 5.14–19, 6.6, and 7.17–24).

86–87. although it turns … one across: In 29.9 Virgil told the pilgrim that the circumference of the ninth bolgia was twenty-two miles; the diameter of this tenth is half of the previous, thus three and a half miles.

88. household: The Italian term is famiglia (see the note to 15.22); Master Adam’s contemptuous use of it expresses his pride in his learning and high social status; we are also reminded that all the damned are members of Satan (see Additional Note 2) and ultimately his servants. In the clear allusions to the biblical Adam in Master Adam’s name and the scene of his sin, we also have allusions to the idea of the human family, all descended from him.

90. dross: Italian mondiglia derives from mondare [to cleanse]; it is the remnant after cleansing.

91–93. Who are the two … right-hand boundary: The pilgrim’s tone is sarcastic, both in his vivid simile and in his metaphoric use of “boundary”–as if Master Adam’s belly were so huge as to constitute a geographic region (another reminder of the symbolism of the body politic). The two souls’ metaphorical “smoking like wet hands” also reduces them in size next to Master Adam. The vapor identifies them as suffering from a fourth disease, thus as a fourth category of falsifier: the symptoms of their disease are those of what medieval writers identify as “putrid fever” (Contini 1953).

97–99. One is the false woman … such a stench: Both Potiphar’s wife and Sinon are formally guilty of perjury. The story of Potiphar’s wife, who tried to seduce Joseph and, when he refused, accused him of attempting to rape her, is told in Gen. 39.7–21. Sinon’s role in inducing the Trojans to take the horse into the city is discussed in the note to 26.58–60. The “stench” (Italian leppo: related to words for “fat,” it seems meant to evoke the smell of burning fat) is the “smoke” of lines 92–93 (cf. 17.3: Geryon “makes the whole world stink,” with note). The issue of perjury is closely related to the counterfeit florin: the Baptist on it is bearing false witness to its quality.

These last two souls mentioned in the Malebolge are protagonists of two major events in the (for Dante) parallel histories of the two chosen peoples: Joseph’s success in Egypt (which led to the enslavement of the Jews and the Exodus) and the fall of Troy (which led to the founding of Rome) (see the note to lines 1–27).

100–129. And one of them … with many words: The famous flyting (exchange of taunts) between Master Adam and Sinon moves from blows (one each) to verbal taunts (four for Master Adam, three for Sinon); the taunts progress from naming sins to naming punishments in purely physical terms, thus gradually downward, each echoing and mirroring the previous one, until reaching Narcissus and his mirror. Vergil’s Sinon, like Master Adam, is of noble birth, a comrade and close relative (Aen. 2.86) of King Palamedes of Nauplia. The progressive degradation of their high status is part of the savage irony. The representation of the damned in this canto begins and ends with the crazy violence of paired souls (cf. 32.43–51 and 124–32).

102–3. with his fist … a drum: Sinon’s blow establishes a relation between Master Adam’s belly and the Trojan Horse, for it alludes to LaocoÖn’s spear (Aen. 2.50–53):

… validis ingentem viribus hastam in latus inque feri curvam compagibus alvum contorsit. Stetit ilia tremens, uteroque recusso insonuere cavae gemitumque dedere cavernae.

[… with his great strength he hurled a huge spear against the beast’s side, its belly curved with ribs. It stood there trembling, and when the womb was struck the hollow caverns resounded and gave a moan.]

The terms referring to Master Adam’s belly (l’epa croia [his taut liver], ventraia [belly], line 54) resound onomatopoetically, like tamburo [drum], related to the name of his disease.

102. on his taut belly: Here, as in 25.82 and 30.119, Dante uses epa, from the Greek word for “liver” (epar), to refer to the belly; for the importance of the liver to Master Adam’s disease, see the notes on lines 52–57 and 73–74.

104–11. and Master Adam … when you were coining: As Sinon’s taunt shows, Master Adam’s blow to his face is an analogue of the hammer blow that stamps the coin.

112–14. You say true there … at Troy: The two falsifiers—one of words, the other of coins—are now condemned to speak only truths, but they are bitter truths that only intensify their pain.

117. for more than any other demon: Sinon is referring to the multitude of false florins coined by Master Adam. As the terminology of minting and the digestion metaphor suggest, there was an analogy between coining and reproduction in the Aristotelian theory: the formal principle in the father’s seed stamps the father’s form on the mother’s blood. Master Adam’s contaminated florins are thus also, at another level, his evil offspring (cf. line 48: “li altri mal nati,” and 3.115: “il mal seme d’Adamo”).

118–20. Remember, perjurer, the Horse … knows of it: The complexity of Sinon’s sin allows Master Adam to derive two taunts from it (as Sinon did from his). The fact that the whole world (all the descendants of Adam; cf. Sinon’s last taunt) knows of Sinon refers to what is perhaps the most painful side of his punishment; the lower in Hell, the more unwilling souls are to be remembered on earth.

123. a hedge before your eyes: An obstacle to sight (like the hill for which the Pisans cannot see Lucca; 33.29–30), emblematic of Master Adam’s inability to see beyond himself.

124–29. Your mouth gapes … with many words: Answering Sinon’s references to his (Adam’s) tongue and belly, Master Adam names Sinon’s mouth and head, continuing the correlation between belly and face established by the two blows that began the quarrel.

128–29. to lick … with many words: That is, Sinon is just as thirsty as Master Adam; the “mirror of Narcissus” is a surface of water, like the pond where Narcissus (named in the Comedy only here) fell in love with his own image and died of desire for it (Met. 3.370–503). The allusion to the standing water of Narcissus’s pool brings the episode to a close with a parallel to the streams of the Casentino of lines 64–66. The entire relation of Master Adam and Sinon has been specular—they are reflections of each other: this is their infernal Narcissism, fixated on the image of their own despair and damnation (see the note on the Medusa, Tydeus, and Menalippus in 32.130–31).

130– 48. I was all intent … a base desire: The two cantos of the falsifiers are thus framed by two rebukes of the pilgrim by Virgil (see 29.1–12), the second considerably more severe. The commentators point out that the entire flyting had taken place under the aegis of a “comic-realistic” stylistic mode related to the abusive tenzone (also a flyting) with Forese Donati of Dante’s youth (cf. Purg. 23.115–20), which the present passage far surpasses in energy and abusiveness, and to which Dante would be in a sense bidding farewell (its authenticity has, however, recently been questioned).

131– 32. Now keep looking … quarreling with you: Dante’s term for “look” (mirare) was, as he knew, the etymon of a common word for “mirror,” miraglio. The pilgrim’s gazing is a form of mirroring (cf. 32.54), and if he and Virgil quarreled, they would be a reflection of Sinon and Master Adam.

134–35. such shame that it still dizzies me: The shame still agitates him. The pilgrim’s capacity for intense shame, resting on his ability to see himself critically, distinguishes him from the falsifiers.

136–41. Like one who … did not think so: The description of a dreamlike, hallucinatory state, within the function of lines 130–48, replaces the blood-drunkenness of the opening of Canto 29 with a confusion whose function is to bring the pilgrim back to himself.

145–47. And mind … such a squabble: Virgil is very close here to being a personification of the pilgrim’s faculty of reason—that is, of his ability to reflect on his actions, essential to freeing himself from the debased specularity of the bolgia.