It has been said that all American heroes are western heroes, and in the past, of course, almost all these heroes have been men.

For all the considerable work done by historians over the last fifty years to correct that imbalance, in popular imagination the “Wild West” is still a man’s world. Served up to us as entertainment, high on thrills if short on historical accuracy, to this day our masculine images of the West—of trappers and huntsmen, of gunslingers, outlaws, and train robbers, of cowboys and gold seekers—are an indelible part of America’s foundation myth. Immortalized in a thousand ballads, novels, movies, and television shows, the names of men like Buffalo Bill, Wyatt Earp, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid still spring easily to our lips. But for all their enduring appeal, not one of them was more than a walk-on part in an epic story that transcends them all.

Women’s experiences are the very core of any true understanding of the reality of the American West, which is not so much a story about gunslingers and cowboys, although they play their part, but a story about one of the largest and most tumultuous mass migrations in history.

When this great migration began, in 1840, the United States of America consisted of just twenty-six states, covering a landmass that was only a fraction of the size it is now. In those days, the “frontier” was more of a vaguely defined idea than an actual place, and one that was in a continual state of flux. Some Americans might have seen it as anywhere west of the Mississippi River, particularly the furthermost borders of the newly created states of Missouri and Arkansas, and what (until July 1836) was then still known as Michigan Territory.1 But for many others it lay, for all practical purposes, along a particular stretch of the Missouri River, the great tributary of the Mississippi, where it flows along the western periphery of present-day Iowa and Missouri.

Beyond this, as the crow flies, lay two thousand miles of prairie, mountain, and desert, much of it designated on contemporary maps as either “Indian Territory” or, simply, “Unorganized Territory.”2 California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, parts of Colorado and Wyoming, and the whole of Texas were at that time still Mexican sovereign territory. Present-day Oregon and Washington States, and large parts of Idaho and Montana, were lands disputed between the US and Britain but as yet belonged to neither. The British-owned Hudson’s Bay Company had a small but vigorous settlement, Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest, but, with the exception of small numbers of traders and trappers and the odd missionary, the rest of this vast continental landmass was almost entirely untouched by whites: a wilderness of almost unimaginable size and beauty.

The westward migrations started slowly. In 1836, two Presbyterian missionaries, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding, became the first white women ever to attempt what was then “an unheard-of journey for females”: a 2,200-mile overland trek, from the Missouri “frontier,” across the Great Plains and over the Rocky Mountains to Oregon country. Encouraged by their success, two years later in 1838 four more missionaries, together with their husbands, joined them in the Pacific Northwest.

The news of these groundbreaking journeys spread fast. If missionaries could endure them, then why not other women settlers too?

Women on horseback

While small numbers of American men had gone west before this time, their presence had for the most part been either transitory or seasonal, usually in line with the hunting and trapping year. It was clear that long-term settlement of these lands could not be achieved by men alone. It was only when women could be persuaded to go west alongside their men that the business of putting down permanent roots could begin.3 Homesteads and farms would then be built, the land would be plowed and crops sown, animals bred and husbanded. Most importantly, future generations would be born to carry on the work their parents had begun. The presence of white women would change everything.

Beginning in 1840, at least one settler family—Mary and Joel Walker and their four children—was emboldened to follow in the missionaries’ footsteps, making the overland journey to Oregon in search of free land and new lives.4 In 1841, a hundred settlers made the journey. In 1842, it was two hundred. In 1843, a thousand. The year after that the numbers doubled again. Soon, stories about Oregon country began to percolate back East, each one taller than the next, and then so magnified that Oregon became known as an almost mythic paradise—the first of many utopias white Americans would look for in the West. Oregon country, it was said, was a land of milk and honey where vegetables grew to prodigious size and the rain only ever fell as gentle dew. With each passing year, the numbers of hopefuls setting out West from the Missouri borderlands grew.

They knew they were making history. These early westward migrations, as well as those that came after them, are uniquely well documented, by women as well as men. But whose version of history do they tell? The millions of square miles of “empty” wilderness (or so it seemed to them) that these early emigrant families traversed were not, in fact, empty. Nor was the “free” land on which they had set their sights in any truthful sense free.

For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, as many as five million people inhabited these lands. By the mid-nineteenth century, their numbers significantly depleted by warfare and diseases brought to them by whites, contemporary estimates indicated that only 250,000 to 300,000 Native Americans remained living in the trans-Mississippi west.5 Organized into many hundreds of different nations, and speaking languages from as many as seven different linguistic families, these were politically and culturally complex societies. Webs of ancient trading trails stretched in every direction, and covered every corner of the land. While some of these nations led relatively simple hunter-gatherer lives, others, such as the seven closely interconnected bands of the Lakota people of the northern plains, were masters of an empire that, in terms of power politics, was every bit as sophisticated and cosmopolitan as that of their mid-nineteenth-century white neighbors. The land they oversaw was not only a source of power and wealth for these Native Americans, but “a dream landscape, full of sacred realities.”1

For centuries, Native people lingered in the recesses of the American imagination as a kind of “dark matter” of history, in the memorable phrase of the historian Pekka Hämäläinen. “Scholars have tended to look right through them into peoples and things that seemed to matter more.” Native Americans, he writes, were “a hazy frontier backdrop, the necessary ‘other’ whose menacing presence heightened the colonial drama of forging a new people in a new world.”2

In the last few decades, particularly in scholarly circles, this perspective has undergone a much-needed and long-overdue shift. Native Americans have reclaimed their place in history as powerful protagonists. The legacies of great leaders such as Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, and Crazy Horse are now as well known as those of Custer, Sheridan, and Sherman.

The experiences of women, however, are still far less easy to come by. What did these tumultuous events feel like to them? After all, within just four decades, Native women would see their entire world changed beyond all recognition.

The testimonies of the Native American women included here, while relatively few in number, are thus, I believe, the most important in this book. At once mirroring and refracting the settler experience, their accounts are essential to our understanding of the mid-nineteenth-century west. The missionary women Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding traveled to Oregon in 1836 because the Cayuse and the Nez Percé, however much they may have later regretted it, wanted them there, and even vied for their services. The combined bands of the Lakota, having initially tolerated the emigrants for the trading opportunities they brought with them, later not only fought back, but for many years bested the US Army, forcing the government in Washington to agree to their own terms.

For the remarkable Josephine Waggoner, a woman of mixed Hunkpapa and Irish ancestry, it was the work of many years to gather together the testimonies of her people, lest the white version of their history be the only one to prevail (although her magisterial work, Witness: A Hunkpapa Historian’s Strong-Heart Song of the Lakotas, was not published until 2013, more than seventy years after her death). To her we owe an exquisite description of a summer spent as a child in Powder River country, the Lakota heartland—the very last moment when her people were free to roam in the time-honored way, living in vast tented villages as many as ten thousand tipis strong. Susan Bordeaux Bettelyoun, Waggoner’s friend and literary collaborator, meanwhile gives us a glimpse of the extraordinarily vibrant, hybrid world of the northern plains, in which relatives from her mother Red Cormorant Woman’s Brulé Tribe lived side by side with French American fur trappers such as her father. Through her testimony we see a vision of what life in the West once was, and might even perhaps have remained, if the currents of history had not dictated otherwise.

But it was not to be. Within a decade of Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding’s arrival in Oregon, the journey that had once been considered impossible for women to undertake had now become almost a commonplace. “The past winter there has been a strange fever raging here,” wrote Keturah Penton Belknap in the spring of 1847. “It is the ‘Oregon fever.’ It seems to be contagious and it is raging terribly. Nothing seems to stop it but to tear up and take a six months trip across the plains with ox teams to the Pacific Ocean. . . . There was nothing done or talked of but what had Oregon in it and the loom was banging and the wheels buzzing and trades being made from daylight until bedtime.”3

While most of these early settlers headed for Oregon country, some chose to go to California, though the route was more challenging and even less well known. In 1849, however, after gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, an estimated thirty thousand people made the journey west. “Gold Fever” replaced “Oregon Fever” in the American imagination (after the Mexican-American War, California was now conveniently part of the US). While the very earliest overlanders had no maps, no guides, and so little information about the route that they were forced, as one put it, to “smell their way west,” by the 1850s wagon trains were traveling as many as twelve abreast and were many hundreds of miles long.

For three decades, from 1840 to the late 1860s, it is estimated that around half a million settlers like Keturah Belknap and her family poured across the Missouri River and headed west on foot, making it one of the largest peacetime mass migrations in history.6 In the twenty years or so that followed the completion of the transcontinental railway in 1869, many millions more would follow these original settlers, filling up the lands in between. Within a period of just forty years, the “frontier” was no more.

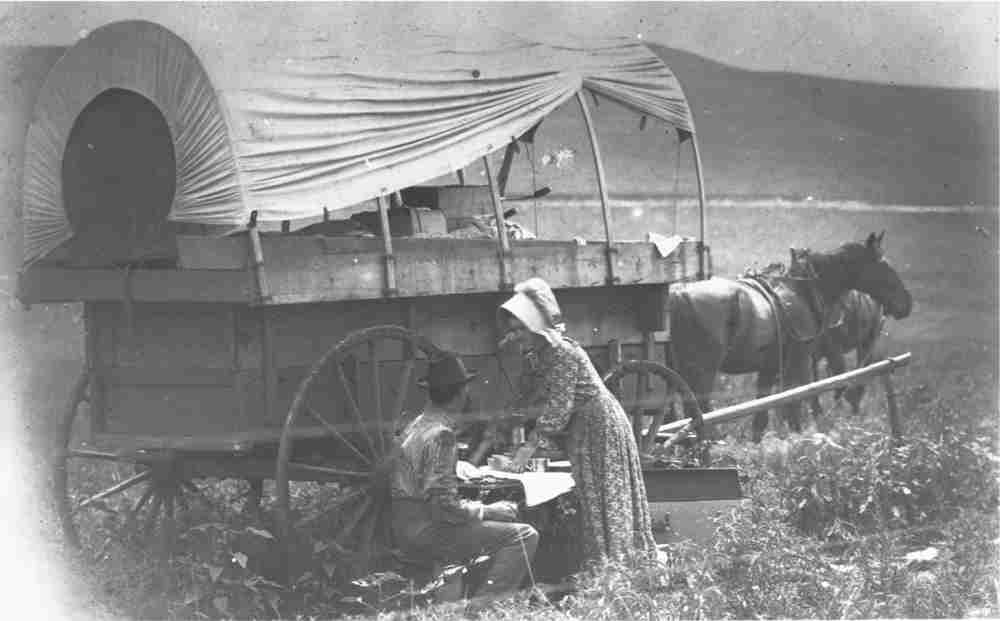

I have beside me as I write a classic photograph taken on what had become known as the “Oregon Trail.” It shows a woman in a sunbonnet standing next to her covered wagon. Bending slightly forward, her face almost obscured by shadow, she is engrossed in laying out lunch for her husband in the shade of the wagon: a loaf of bread and a tin mug full of coffee, some beans and a slice of bacon, all carefully arranged on a neat white cloth. Toward the front of the wagon, the white canvas covering—perhaps stitched, and possibly even woven, by her own hands—has been hitched up, revealing the contents inside: stores of food and clothing, perhaps (we might guess) a treasured heirloom like china plates or a family Bible, her sewing basket, her husband’s work tools. Whatever was inside, it was likely to be everything she had in the world. Their horses, grazing to one side on the open prairie, still look sleek and well fed, and the cloth on the makeshift table is pristine, so the photograph is likely to have been taken early on in their journey.

This peaceful, pastoral scene belies the very real dangers settlers faced on their 2,200-mile journey west.

I first came across this image quite by chance. On a visit to the famous Parisian bookstore Shakespeare & Co., I picked up a well-thumbed secondhand copy of Cathy Luchetti’s Women of the West, a collection of sublimely beautiful black-and-white photographs of women during the westward migrations. It has been on my shelves for more than ten years now, and I often take it down to ponder these all but forgotten lives.

Had the woman in my photograph, like so many of her fellow women travelers, just recently bid farewell to parents, siblings, and every friend she ever had, with the almost-certain knowledge that she would never see them again? Who knows how many more months’ traveling were still ahead of her. Who knows how many of her few remaining poor possessions had to be jettisoned along the way to lighten the load for their, by now, half-starved and exhausted animals. Who knows if their supplies even held out. Did she, like so many of the early settlers, all but starve to death along the road? Or did some other catastrophe lie in store: cholera or “camp fever,” or a pregnancy gone wrong, or perhaps attack or even capture by those she had been raised to know as “savages.”

Or did she, quite simply, just get lost?

This photograph is a classic, some might say a cliché, of western emigration. The woman in it appears like a figure sprung directly from the pages of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie. Wilder was, of course, herself the child of restless pioneers, and the extraordinary power of her stories lies in her ability to extract exactly the same kind of details from her own lived experience—the warp and weft of everyday life—as can also be found in so many of the diaries and journals included in this book. Despite being altogether quieter tales and despite their relative scarcity, Wilder’s stories, so passionately beloved by millions not only in America but throughout the world, have proven at least as influential as any “cowboy” movie in shaping our vision of the West, sealing (in the words of Wilder’s biographer Caroline Fraser) complex and ambiguous reactions to western emigration inside the “unassailably innocent vessel” of a children’s story.4

While some of the women in this book are white women with myriad similarities to the figure in my photograph, there are large numbers who do not fit that picture at all. They instead encompass an extraordinarily diverse range of humanity, of every class, every background, and of numerous different ethnicities, many of them rarely represented in histories of the West. From the very earliest days of the emigration, many free-born African Americans found themselves in the grip of “Oregon Fever.” Although their experience would prove profoundly different from that of whites, they too made their way west, urgently motivated by their state of “unfreedom” in the hostile East. In the later years of the emigration, these white and Black Americans were joined along the rapidly proliferating trails by hundreds of thousands of Europeans, immigrants from as far away as Scandinavia, Germany, Russia, Ireland, and Great Britain, all eager to claim land and start new lives. Others, such as Ah Toy, one of many thousands of Chinese sex slaves trafficked against their will and sold openly on the docks of San Francisco, or the Mississippi slave Biddy Mason, had no choice in the matter.

Most of the women in this book, however, chose to go west. For many it was the prospect of free or very cheap farmland that drew them, and the chance to escape from the economic depression that throughout the 1830s had ruined many farmers in the East. For those who went to California, it was the lure of gold. For others, such as Catherine Haun, it was little more than a honeymoon jaunt and (incredibly) a health cure. Others would have more complex reasons. Miriam Davis Colt dreamed of starting a utopian vegetarian community on the plains of Kansas. For Priscilla Evans, a Welsh convert to Mormonism, it was religious freedom and the prospect of helping found a City of the Saints in Utah’s desert salt flats. In 1856, Evans and her husband, having sailed from Liverpool to Boston, were among nearly three thousand “handcart pioneers”—fellow converts from Germany, Wales, Scotland, Sweden, and Denmark—who completed the punishing five-month overland journey from Iowa to Salt Lake City on foot. Too poor to afford the ox-drawn wagons used by most settlers, they trudged for up to fifteen miles a day, pulling all their possessions behind them in handcarts.

Others had experiences so extreme that their stories gripped the public imagination even in their own lifetimes: thirteen-year-old Virginia Reed, whose company, the Donner-Reed party, was reduced to cannibalism when they became trapped in the winter snows of the Sierra Nevada, or Olive Oatman with her mysterious facial tattoos, adopted by the Mohave, with whom she lived for several years in Arizona after her family had been massacred by a neighboring Tribe. The account Oatman would later write about her experiences became an instant bestseller. Life Among the Indians remains one of the most famous “captivity narratives” of all time, transforming Olive Oatman herself, in all her otherworldly Gothic beauty, into one of America’s first media stars.

Still others seemed barely to know why they were going at all, other than feeling a vague restlessness that even they found hard to justify. Sarah Herndon, a young woman who made the journey west in 1865 in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, pondered exactly that. At the end of a glorious day in May—“the sky most beautifully blue, the atmosphere delightfully pure, the birds twittering joyously, [when] the earth seems filled with joy and gladness”—she sat down in the shade of her prairie schooner, a blank book in her hands, pen poised ready to record the events of their first day on the road. “Why are we here?” she wrote, on the very first page of her journal. “Why have we left home, friends, relatives, associates, and loved ones, who have made so large a part of our lives and added so much to our happiness?

“Are we not taking great risks, in venturing into the wilderness?” she wondered. “When people who are comfortably and pleasantly situated pull up stakes and leave all, or nearly all, that makes life worth the living, start on a long, tedious, and perhaps dangerous journey, to seek a home in a strange land among strangers, with no other motive other than bettering their circumstances, by gaining wealth, and heaping together riches . . . it does seem strange that so many people do it.”5

The motives did not seem to justify the many inconveniences and perils of the road. “Yet how would the great West be peopled were it not so?” she wrote. Although Herndon does not say so in so many words, vast numbers of Euro-Americans had come to believe, as she did, that it was their “manifest destiny” to move west.7 “God knows best,” she concluded. “It is, without doubt, this spirit of restlessness, and unsatisfied longing, or ambition—if you please—which is implanted in our nature by an all-wise Creator that has peopled the whole earth.”

This claim, outrageous as it might sound to us today, was one that would have been shared by all her fellow overlanders. The fact that “the great West” was already richly peopled caused them not even the smallest moral hesitation in setting forth. It is hardly surprising then that within a year of Sarah Herndon’s journey, the once-peaceful emigrant trails had erupted into violence and bloodshed.

The experiences of the women in this book, and the part each played in the transformation of the West, are so diverse that they defy any easy categorization. They have only one thing in common: whoever they were, and wherever they came from, their decision to uproot themselves from everything they held dear and make the journey west was the defining moment of their lives. More than eight hundred diaries and journals written by women and describing their experiences are known to exist, both published and in manuscript form.8 More unusual still, they range from the literary musings of well-to-do, highly educated middle-class women to the poignant streams of consciousness of the barely literate. For those who either did not or could not write—enslaved African Americans, for example, were forbidden by law from even attempting to do so—a wide range of other documentary evidence exists: not only in oral records, but in census and law reports, US Army records, and many thousands of newspaper and magazine articles.

They do what women’s records always do: they tell us what day-to-day life was really like. They vividly describe the practical realities of a particular time and place, sometimes in excoriating but often in marvelous detail too. One explains how the women on the trail would gather together in groups to relieve themselves, standing in a circle, each one holding up her skirts to give the others much-needed privacy. Another tells of the accouchement of a woman who gave birth to a child in the middle of a prairie thunderstorm, her female friends wading up to their knees in muddy water as they rallied round to help. Yet another gives us an extraordinary account of what it was like to feel the ground tremble at the approach of a 100,000-strong herd of buffalo—while viewing them, at a safe distance, through opera glasses. There is a freshness, and a drama, about their version of events, even quite ordinary ones, that is entirely undimmed by time.

The accounts by Native American women are more powerful still, although for the most part they make for somber reading. Who could ever forget the devastating testimony of Cokawiŋ, a Brulé elder left for dead after she had been shot by a US soldier at the Battle of the Blue Water, binding up her own wounds with strips of skunk skin? Or that of Sally Bell, from the Sinkyone Tribe in California, whose entire village, including almost all her family, was massacred by a vigilante militia during the Gold Rush years. Or that of Sarah Winnemucca, a Northern Paiute, whose most vivid childhood memory is of being buried alive by her mother, up to her neck in the ground, to hide her from a party of whites.

Time and again, these Native American women’s accounts show how it was not only human but environmental destruction that followed inevitably in the settlers’ wake. In her deceptively simple parable, Old Lady Horse, a Kiowa, gives us a piercing lament for the bison herds on which her people depended, some thirty million of which once roamed the prairies, but which she saw disappear entirely from the southern plains, hunted to extinction by whites.

This book covers the forty-five-year period from 1836, the year Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding made their journey west, to 1880, the year when the US Census Bureau declared that the “frontier” was no longer. It is not intended to be a comprehensive history of that time. By confining myself mostly, but not exclusively, to the principal emigrant trails to California and Oregon, I am aware that there is much that I have necessarily left out (events in and around what is now Texas, for example, are beyond the scope of this book). But by telling the stories of just some of the women who lived through those times, I hope that the general arc of history will become clear.

This has not been an easy book to write, but of all the books I have written it is the one that means most to me. Even though there were many times when I felt overwhelmed by the sheer weight of material, both physically and emotionally, and even though the testimonies contained here have led me to write a story that has proved quite different from the one I thought I was going to write, I have come to feel a profound connection with these women. They were wives and daughters, mothers and grandmothers—just as I am, and just as are many of you reading this book. They were doing what women always do: they kept going, looking after their families as best they could, no matter what the circumstances. While many women lived to tell their tales about their part in the westward migrations, a great number of them did not. Included here are some of the most extreme stories I have ever come across, and I felt a particular responsibility to tell these truthfully. It is not a simple picture. For every moment of heroic resilience, I found its counterpart in savagery and betrayal. For every story of hope and new beginnings, I found another of suffering and death. But as I went along, I also came to realize that to make simple heroes or villains of either side is to make caricatures of both, to allow cardboard cutouts to take the places of their all-too-human complexities.

For better and for worse, women were at the beating heart of everything that happened.

This is their story.