Little could Virginia Reed have envisaged, when she advised anyone who wanted to follow them to California not to be deterred by their story, “to take no cutofs and hury along as fast as you can,” just how prophetic her words would turn out to be.

In a curious incident, and one that is easy to skim over altogether in her devastating account of starvation and cannibalism in the Sierra Nevada, she refers to a discovery made by John Denton, the Donner family’s teamster. Denton was an Englishman from Sheffield, a gunsmith and “gold-beater” by trade, who had shared the Reeds’ cabin. One evening, when he was trying to fashion some fire irons out of rocks by chipping pieces off them with his cane, his attention had been caught by fragments of something bright and glittering inside the stone. “Mrs. Reed, this is gold,” he had exclaimed. Virginia’s mother had replied bitterly that she wished it were bread, but Denton was undeterred. Chipping away at the rocks, he had soon collected about a teaspoonful of the shining particles, vowing then and there that “If ever we get away from here, I am coming back for more.”121

But John Denton, of course, whose frozen, emaciated body was later discovered with a small buckskin pouch of gold dust still in his pocket, did not live to fulfil his wish. Just two years later, however, an estimated thirty thousand people would set out West with exactly the same dream.

On January 24, 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. James Marshall, a carpenter from New Jersey who was working for John Sutter at the time, had spotted some flakes of gold in the river. Very soon after, other workers at the mill made similar finds. In an almost-perfect dovetailing of events, barely a week later, on February 2, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in faraway Mexico City, bringing an end to the two-year Mexican-American War. Under the terms of the treaty, a vast majority of what is now the American Southwest and West, including the whole of California, was transferred to the United States.79 The combination of these two events would change Americans’ perception of the West forever.

At first John Sutter was dismayed. Predicting disaster ahead for his business ventures should the news get out, he tried to keep the discovery under wraps, but to no avail. Within just two months, 273 pounds of gold had been recovered from the Sutter’s Mill area. It would prove impossible to keep this treasure trove a secret any longer.

A man waving a vial of gold fragments in the saloon bars of Yerba Buena lit the tinderbox. It is estimated that by the middle of June three-quarters of the men living there had abandoned the port—including all the tall ships anchored there—and were flooding into the Sierra Nevada foothills. The Gold Rush had begun.

The Oregon Fever of the early 1840s was as nothing compared to the California “Gold Fever” that now gripped the nation. Intoxicating stories soon began to filter back East. Even though most of these owed more to myth than to reality, the suggestion that the wealth of Croesus could be had by merely “dipping one’s hand into a sparkling mountain stream” soon took hold.122 It was, as one historian has written, “the beginning of our national madness, our insanity of greed.”123

Until this time, the yearly emigration to Oregon and California had numbered a few thousand at most. Now, almost overnight, the steady trickle of farmers and homesteaders making their way west became a raging torrent as gold seekers in their tens of thousands rushed in from all corners of the globe: Chinese laborers, Mexican farmers, clerks from London, tailors from eastern Europe, Spanish aristocrats, sailors from Australia. Boats set sail from almost every port in South America.

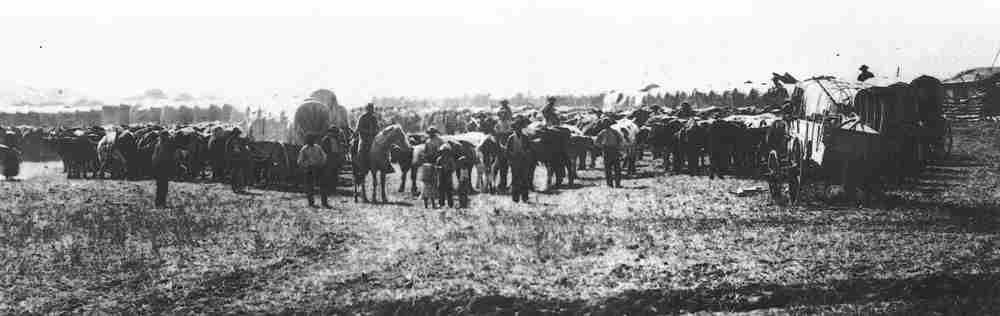

In 1848, before stories about the discovery of gold had had a chance to percolate east, four thousand overlanders set out West. The following spring, in 1849, thirty thousand set out from the Missouri borderlands and headed to California. In 1850, fifty-five thousand followed them. While a great proportion of these were single men, many families of women and children were among them. Instead of relatively modest wagon parties such as those traveled in by Virginia Reed and Keturah Belknap, so many outfits left Independence that April that the line of wagons stretched for hundreds of miles, as far as the eye could see.

“We have been eighteen days on the plains, amid the greatest show in the world,” wrote one observer. “The train is estimated to be 700 miles long, composed of all kinds of people, from all parts of the United States, and some of the rest of mankind, with lots of horses, mules, oxen, cows, steers.” 124 “It seemed to me that I had never seen so many human beings in my life before,” wrote one woman bound for the California gold mines in 1850. At one point, where the branches of two separate trails converged along the Platte River, the sheer numbers of wagons were like nothing she had ever seen before. “When we drew nearer to the vast multitude, and saw them in all manner of vehicles and conveyances, on horseback and on foot . . . I thought, in my excitement, that if one-tenth of these teams and these people got ahead of us, there would be nothing left in California to pick up.”125

By midcentury, tens of thousands of settlers were leaving the Missouri “jumping off” towns every spring.

For California’s Indigenous people, many of whom were already living in semi-slavery under the Mexican mission system, and those, such as Sarah Winnemucca’s Tribe, the Northern Paiute, living on the peripheries of the gold fields, it would mark the end of the world as they knew it.

Gold became the impetus for a new kind of emigration altogether. Now it was not only families from relatively humble backgrounds—the “backwoodsmen,” in Francis Parkman’s phrase—but middle-class men and women from prosperous homes. “On the streets, in the fields, in the workshops, and by the fireside, golden California was the chief topic of conversation,” wrote Catherine Haun, a young bride from Iowa. The effects of the economic depression, begun in 1837, still resonated throughout the Mississippi Valley, and, like many others, the couple were in financial difficulties. The stories of gold that were beginning to sweep eastward fell upon willing ears. “We . . . longed to go to the new El Dorado and ‘pick up’ gold enough with which to return and pay off our debts,” Catherine wrote, believing it was a chance to exchange their “comfortable homes—and the uncomfortable creditors—for the uncertain and dangerous trip, beyond which loomed up, in our mind’s eye, castles of shining gold.”126

For Catherine Haun, traveling west in 1849 with her lawyer husband and his brother, the reasons for going were complex ones. Her sister, while still young, had recently died of consumption, and she too “had reason to be apprehensive on that score.” Her doctor, seeing the danger of another winter of intense cold in Iowa, had advised a complete change of climate. His first recommendation was a long sea voyage, but instead he “approved our contemplated trip across the plains in a ‘prairie schooner,’ for even in those days an out-of-door life was advocated as a cure for this disease.” Incredibly, it also appealed to the recently married couple “as a romantic wedding tour.”

“Who were going? How best to ‘fix up’ the ‘outfit’? What to take as food and clothing? Who would stay at home to care for the farm and women folks? Who would take wives and children along?”—these were the questions on everyone’s lips. “Advice,” Catherine remembered, “was handed out quite free of charge and often quite free of common sense.”

Settlers had always tended to take too many belongings with them, and the Hauns were no exception. In addition to four servants—a cook and three teamsters—their outfit consisted of four wagons. One of these was given over entirely to barrels of alcohol for their consumption on the journey, while two others were loaded up with merchandise which they fondly hoped to sell “at fabulous prices” when they arrived at the other end. “The theory of this was good,” Catherine recalled, “but the practice—well, we never got the goods across the first mountain.” As was so often the case, these entirely superfluous wares would be abandoned beside the trail, for those who came after them to plunder at their will. The alcohol they buried in the ground, “lest the Indians should drink it, and frenzied thereby might follow and attack us.”

In the fourth wagon, Catherine took her trunk of “wearing apparel,” the contents of which she detailed lovingly in her account. These consisted of “underclothing, a couple of blue checked gingham dresses, several large stout aprons for general wear, one light colored for Sundays, a pink calico sunbonnet and a white one intended for ‘dress up’ days. . . . My feminine vanity had also prompted me to include, in this quasi-wedding trousseau, a white cotton dress, a black silk manteau trimmed very fetchingly with velvet bands and fringe, also a lace scuttle-shaped bonnet having a wreath of tiny pink rosebuds, and on the side of the crown, nestled a cluster of the same flowers. With this marvelous costume I had hoped to ‘astonish the natives’ when I should make my first appearance upon the golden streets of the mining town in which we might locate.” As she remarked, with a certain self-deprecating irony: “Should our dreams of great wealth acquired overnight come true, it might be embarrassing not to be prepared with a suitable wardrobe for the wife of a very rich man!”

As it turned out, she spent almost the entire journey in the same dark woolen dress, learning, as countless other women had done before her, that it “economized in laundrying, which was a matter of no small importance when one considers how limited, and often utterly wanting were our ‘wash day’ conveniences. The chief requisite, water, being sometimes brought from miles away.” But this hard-won knowledge was many long, toilsome months into the future.

Many women wrote about the pain and fear of parting with family and friends, but Catherine Haun’s account, which she dictated many years later to her daughter, is unusually honest.

The weather in the spring of 1849 was particularly inclement. Even at the end of April there was still snow on the ground, and torrential rain had made the road almost impassable. The beginning of the Hauns’ journey was painfully slow. It was not long before Catherine’s courage failed her altogether. The first night they stopped at a farm, where they found a bed for the night. “When I woke the next morning a strange feeling of fear at the thought of our venturesome undertaking crept over me,” she recalled. “I was almost dazed with dread.” She went outside into the sunny farmyard, where the contrast between the “peaceful, happy, restful home” before her and the “toil and discomfort” of the previous day’s journey “caused me to break completely down with genuine homesickness and I bust out into a flood of tears.”

“I remember particularly a flock of domesticated wild geese. They craned their necks at me and seemed to encourage me to ‘take to the woods.’ Thus construing their senseless clatter, I paused in my grief to recall the intense cold of the previous winter and the reputed perpetual sunshine and wealth of the promised land.” Wiping away her tears, lest they betray her feelings, she added: “I have often thought, that had I confided in [my husband] he would certainly have turned back, for he, as well as the other men of the party, was disheartened and was struggling not to betray it.”

They had not been traveling more than a day when their first “domestic annoyance” occurred. The cook they were taking with them had been followed by her “Romeo,” who had had no difficulty in persuading her to defect. Catherine was now the only woman in their party, and by her own admission had never prepared so much as a cup of coffee for herself before. She surprised everyone, herself included, by offering to do the cooking “if everyone else would help.”

Catherine Haun’s doctor’s recommendation of the journey west as a health cure was, on the surface of it, not quite so outrageous as it might seem. Many women wrote about the fact that their health, and certainly their appetites, were much improved by the fresh air and exercise. Catherine herself noted that, as promised, the outdoor life completely restored her health “long before the end of our journey.” Another young woman, traveling that same year, described how her invalid mother, who at the beginning of the journey was so weak that she had to be physically lifted in and out of the wagon, “now . . . walks a mile or two without stopping, and gets in and out of the wagons as spry as a young girl.”127

Middle-class etiquette sometimes followed these middle-class women, even onto the wide-open prairies. “Mr. Reade came with six young ladies to call on us this morning, also one gentleman from the Irvine train,” recorded one young woman on her journey west. “They had gone down into their trunks and were dressed in civilization costumes. They were Misses Nannie and Maggie Irvine—sisters—their brother, Tom Irvine, Mrs. Mollie Irvine, a cousin—Miss Forbes, and two other young ladies whose names I have forgotten. They are all very pleasant, intelligent young people.”128

But the sheer weight of travelers was changing the once-pristine landscape. Wagon trains that had once left the Missouri River in small, self-contained groups now surged west in numbers that suggested nothing so much as “a vast army on wheels—crowds of men, women and lots of children and last but not least the cattle and horses on which our lives depend.”129 Sometimes the wagons traveled as many as twelve teams abreast, their billowing white canvas tops glinting in the sun. This put even greater pressure on already-stretched resources such as drinking water, while the litter and waste left behind by each succeeding party made for some disgusting conditions for those who came after, such as the “unendurable stench that rose from a ravine that is resorted to for special purposes by all the Emigration.”130 One woman was so revolted by the reek of human ordure that greeted her when she arrived at one of their camps she declared to her husband that if he did not drive her to a cleaner place to camp and sleep that night “I will take my blanket and go alone.”131 Usually, however, there was simply no option but to endure it as best they could.

With so many settlers and gold seekers, the vast majority of them men, now thronging the trail, and with ever more crowded campsites, privacy was an increasing problem. “Women told of escorting each other en masse behind the wagon train to stand in a circle facing outward, holding their skirts out to provide a bit of shelter for the one taking a turn.”132

Insanitary conditions, and lack of an adequate water supply, soon became much more than just a trial to female modesty. Disease and “fevers” of all kinds thrived in overcrowded, filthy campsites. The indignity of coping with the effects of dysentery, one of the commonest (and often fatal) ailments on the trails, must have been a particular misery for those who were afflicted by it.

Like many women, Catherine Haun took with her a well-stocked medicine box. Principal among her remedies were the well-known staples of quinine, opium, and whiskey; she also took hartshorn, an early form of smelling salts, as a bizarre antidote for snake bites (perhaps it was effective in dealing with the shock), and she used citric acid against scurvy—a few drops of which added to sugar and water “made a fine substitute for lemonade.”

A cheerful glass of lemonade was likely to have been just as effective as many of the other remedies and herbal tinctures to which women often resorted on the trails. Dysentery was treated with either dried whortleberries or half a teaspoon of gunpowder; a mixture of turpentine and sugar was said to relieve stomach complaints caused by parasites; and thickened egg whites in vinegar was used as a cough syrup. The recipe for a “Worm Elixir” included a tincture made up of saffron, sage, and tansy leaves, which should then be suspended in a pint of brandy for two weeks, a teaspoon of which should be given to children “once a week to once a month as a preventative. They will never be troubled with worms as long as you do this.”133 These remedies were usually harmless enough, and often comforting; they certainly did less violence to the body than the bleedings, blisterings, powders, and pills of uncertain provenance so often prescribed by male doctors.

One of these more sinister nostrums, bluemass, was included by Catherine Haun in her medicine supplies. Bluemass was a nineteenth-century cure-all, popularly used for a wide range of ailments from toothache and constipation to the pains of childbirth, parasitic infections, and tuberculosis. Recent analysis, in a specialist British laboratory, of some of these “blue pills” has shown the basis of bluemass to have been a compound of powdered licorice (five parts), marshmallow root or althaea (twenty-five parts), glycerin (three parts), and honey of rose (thirty-four parts). However, one third of this pleasant-tasting but otherwise entirely useless concoction was a dangerously high dose of mercury, a substance so toxic to the body that its prolonged usage, far from curing anything, eventually caused symptoms ranging from loosening of the teeth and blackening of the gums to vomiting and stomach cramps, clinical depression, and renal failure.80

But in 1849, when Catherine Haun embarked on her journey, there was nothing in her medicine box that had even the smallest chance of curing the greatest killer of them all that year: cholera.

The infection had first started in the Ganges delta and had spread across Asia and finally to Europe. The global pandemic had reached the US in 1848, thought to have been brought in on a ship, the New York, which had arrived from London, where the disease was then raging, in December. Seven passengers had died on board; the ship was put into quarantine, but it was too late. Five thousand people died in New York City alone.

Soon the disease had spread all over the United States, with the Mississippi Valley being particularly hard hit. Settlers, many of whom, like Catherine Haun, had decided to travel west to escape the diseases and unhealthy climate in the East, would become the very means by which the pathogen would spread.

The crowded and insanitary trails, where families ate, slept, and defecated in the closest proximity to their neighbors and traveling companions, created perfect conditions for the disease to proliferate. “Today we have passed a great many newmade graves & we hear of many cases of cholera . . . we are becoming fearful of our own safety,” wrote Mrs. Francis Sawyer. Two weeks later, her worst fears had been realized. “Dr. Barkwell . . . informed us that his youngest child had died on the plains. . . . The trials & troubles of this long wearisome trip are enough to bear without having our hearts torn by the loss of dear ones.”134

Wood from abandoned wagons was often used to fashion makeshift coffins, causing one woman to glance nervously at the sideboards of her own conveyance, “not knowing how soon it would serve as a coffin for one of us.” There are records of burials lying in rows, fifteen or more across, and some diaries do little more than record the proliferation of wayside graves.

| May 17th | . . . Saw two graves |

| May 18 | There were two old graves close by saw two more at some distance saw one new grave |

| May 27th | started at six, saw three old graves and two new ones . . . |

| May 30th | Saw several graves today one with inscription . . . |

| We counted 5 graves close together only one with inscription | |

| June 1 | Graves now are partly dug up |

| June 7th | 7 new graves today |

| June 9th | Most graves look as if they were dug and finished in a hurry |

| June 16 | Men digging a grave for a young girl. It is common to see beds and clothing discarded by the road not to be used again. It indicates death. |

| June 20 | A young lady buried at [Independence] Rock today who had lost mother and sister about a week ago135 |

There is barely an account of the 1849 journey that does not mention similarly disturbing sights. Graves were sometimes recorded with the same obsessive attention as miles traveled, as in this chilling record kept by a woman traveling with her family from Illinois to Oregon in 1852:

| June 25 | . . . Passed 7 graves . . . made 14 miles |

| June 26 | Passed 8 graves |

| June 29 | Passed 10 graves |

| June 30 | Passed 10 graves . . . made 22 miles |

| July 1 | Passed 8 graves . . . made 21 miles |

| July 2 | One man of [our] company died. Passed 8 graves made 16 miles |

| July 4 | Passed 2 graves . . . made 16 miles |

| July 5 | Passed 9 graves . . . made 18 miles |

| July 6 | Passed 6 graves . . . made 9 miles |

| July 11 | Passed 15 graves . . . made 13 miles |

| July 12 | Passed 5 graves . . . made 15 miles |

| July 18 | Passed 4 graves . . . made 16 miles |

| July 19 | Passed 2 graves . . . made 14 miles |

| July 23 | Passed 7 graves . . . made 15 miles |

| July 25 | Passed 3 graves . . . made 16 miles |

| July 27 | Passed 3 graves . . . made 14 miles |

| July 29 | Passed 8 graves . . . made 16 miles |

| July 30 | I have kept an account of the dead cattle we have passed & the number today is 35 |

| Aug 7 | We passed 8 graves within a week . . . made 16 miles |

| Sept 7 | We passed 14 graves this week . . . made 17 miles |

| Sept 9 | We passed 10 graves this week . . . made 16 miles |

| Oct 1 | We have seen 35 graves since leaving Fort Boise136 |

Even more unnerving, if possible, was the sight of gravediggers actually at work. Or the poignant sight, often recorded, of graves being dug before the victim was even dead, “so as to save time.”

Even those who survived could find themselves in a pitiful situation, and women were particularly vulnerable. While Catherine Haun’s company was among the very few to escape the scourge, one day a “strange white woman” with torn clothes and disheveled hair, carrying a little girl in her arms, came rushing out of the wilderness into their campsite. The woman was in a state of near collapse, “trembling with terror” and barely able to walk from hunger. The little child, who at the sight of them “crouched with fear and hid her face within the folds of her mother’s tattered skirt,” appeared just as traumatized.

At first the woman was too distressed to give any account of herself “but was only able to sob: ‘Indians,’ and ‘I have nobody nor place to go to.’ ” The Haun party took her in, and after some food and a night’s rest, they were finally able to hear her story. The woman, who was from Wisconsin, was called Martha. It transpired that she had been traveling in a family group made up of her husband, their two children, and her brother and sister. When her husband and sister had contracted cholera, the other family members had made the fatal mistake of separating themselves from the rest of their company in order to look after them. “The sick ones died and while burying the sister, the survivors were attacked by Indians, who, as she supposed, killed her brother and little son.”81

Martha and her little girl had walked for three days through the wilderness trying to find help. She had seen another emigrant train in the distance but had convinced herself that there were “Indians” in the vicinity between them and herself and found it necessary to conceal herself behind trees and boulders in order to avoid them. At one point she had been forced to take a detour “miles up the Laramie [River]” in order to find a crossing place, but the swift current “had lamed her and bruised her body.”

In fact, the greatest danger she faced was not attack by Native people but starvation and exposure. Martha had survived by eating raw fish, which she caught with her hands, and, on one occasion, a squirrel that she had killed with a stone. Finally, on the third day, attracted by the sound of voices and firelight coming from the Hauns’ camp, “in desperation she braved the Indians around us and trusting to darkness ventured to enter our camp.”

Martha remained with the Hauns’ wagon train all the way to Sacramento, California. She had pleaded with them to take her back to Independence, but they had now come too far to make a return there possible, and she was reconciled to “a long and uncertain journey with strangers.” Two days into their resumed travel they found her deserted wagon, from which the horses and all her clothes had been “stolen by the Indians.”

If Martha’s clothes had indeed been stolen by Native Americans, rather than simply picked over by other settlers, it was likely to have had fatal consequences. The cholera brought by the overlanders spread with devastating rapidity among the plains Tribes who lived, hunted, and traded along the westward-bound trails. It was not only the settlers’ stinking campsites and rudimentary graveyards—where bodies had on occasion been buried so hastily that heads and limbs were sometimes still visible sticking out of the ground—that became a source of infection. Almost anything belonging to the settlers—their wagons, supplies, and equipment abandoned or cached by the roadside, soiled clothing and bedding, and even food—could potentially carry the contagion (which is spread by feces). Perhaps most terrible of all, however, was the contamination of their water sources. Infected people washing, bathing, and defecating on the banks of rivers and streams soon turned the life-giving resource into deadly poison.

At first, many Native people turned to the settlers themselves for help, often approaching wagon trains to ask for medicine, which in turn exposed them still further to infection. “Many died of the cramps,” reads a Lakota winter count for that year, its pictograph showing the agonized body of a man dying from diarrhea and dehydration, cholera’s most deadly symptom. That summer, a party of the Army Corps of Engineers, heading along the North Platte, came across a group of five tipis abandoned near the river. Approaching cautiously, they found that the tipis were in fact tombs, in which the dead bodies of a number of Lakota had been ritually laid out. Most poignantly, in the smallest tipi they found the lovingly arranged body of a young teenage girl “richly dressed in leggings of fine scarlet cloth,” her decomposing body “wrapped in buffalo-robes.”137

But as the contagion spread ever more quickly, there was often no time to dress and paint their dead. The remarkable Hunkpapa historian Josephine Waggoner, who spent several decades of her life recording her people’s oral history, gives a vivid description of the sense of panic that gripped them as the disease, previously unknown among them, struck with all the terrible force of a storm. “It came up from the south with the hot winds, which drove the malady into sweeping flames as though it were a prairie fire,” she wrote. “It took the weak and strong, the young and the old; it was a raging epidemic.”

While the disease started along the Platte River, where the overlanders were most numerous, it soon spread north, ripping through village after village. Presenting, at first, “with a bilious attack,” within a few hours “the sufferers would be seized with all the symptoms of cholera.” Usually, death followed within a matter of hours. “The well ones forsook the sick, mothers forsook their children who took it. A panic struck the whole tribe; they fled north, leaving those that died rolled in blankets or robes. Whole villages were swept away; there were tents and camps that were left standing where whole families had died and no one left alive to bury them.

“The odor from the dead bodies could be scented for miles and above the deserted tents buzzards were sailing; sometimes flocks of crows flew out of the tops of the tents. This was the desolate time remembered by those who survived the epidemic. Those who were seeking help were shot at when they came anyways near the well ones. In this way, some came to a quicker end.” Josephine Waggoner had been told this by the wife of the great Lakota chief Spotted Tail. “Mrs. Spotted Tail was a survivor; she told the conditions that existed at that time.”138

Red Cormorant Woman

Susan Bordeaux Bettelyoun, who in her later life would collaborate with Josephine Waggoner on her own account of the history of her people,82 gives an even more graphic description of the devastation caused by the cholera epidemic. Susan was the daughter of Red Cormorant Woman, a Brulé Lakota, and a woman greatly honored in her band. In 1841 she had married the French American fur trader James Bordeaux. The two had met on the North Platte River, where Red Cormorant Woman’s band often camped in order to exchange goods with the fur traders and trappers, many of whom, like Susan’s father, were of French descent. James Bordeaux operated a trading post and road ranch just eight miles east of Fort Laramie, on the North Platte River. Susan’s early childhood was spent living in close proximity to the emigrant road, and she witnessed firsthand the growing tide of white migration. Although Susan herself was born in 1857, well after the cholera epidemic, many years later she would record her family’s memories of the havoc it wreaked. “As a small child I was not talkative, but very observant and could remember well incidents and faces and names. Any stories or tragedies related to me were never forgotten.

“During the time of cholera, which had reached Laramie by 1849 it was a very dry year. There had been no rainfall all spring and summer. The disease seemed to be in the air and even in the dust. The cholera broke out in places all over so suddenly and without warning that no one knew what to do; even running water brought on the disease. People were afraid to drink water.”

The disease did not only spread among the Lakota. “It was among all the tribes in the remotest parts of the Rocky Mountains. Thousands of Blackfeet were reported to have died from it; the Snake Indians, the Crows, were greatly reduced in numbers. Some of these, it was told, killed their dying and then killed themselves. People fled from each other as the disease made its appearance. No one stopped to bury the dead.” Sometimes holes were cut in the ice, and the dead were thrown in these. “It was reported that many suicides were committed here. Those that lost loved ones jumped right into these holes preferring a watery grave.” According to Susan Bordeaux, the Mandan were reduced from three thousand people to just thirty adults, while half the Rees and the Gros Ventres died. In 1849 alone, the Sicangu lost one in every seven of their people. “All up and down the Yellowstone and the Missouri there were thousands of Cheyennes and Assiniboines lying unburied.” Even Tribes as far north as Canada were affected. “In all parts of the West there was no one spared; no matter what tribe they belonged to, they were being swept off the face of the earth. It was the most heartrending circumstance. . . . It was common for a long time for a hunter to find skeletons any place, a few years after, lying where the sick had been dragged away and left, the bones bleached as white as driven snow.”139

When she saw that the cholera was coming, Susan’s mother, Red Cormorant Woman, had locked up their ranch and taken all her children and some other relatives who were staying with her to the house of a neighbor, another French American trader, Joseph Robidoux. Robidoux ran a successful blacksmith shop, right on the Oregon Trail at Horse Creek, near Scott’s Bluff. So far, the disease had not reached Robidoux’s ranch. Then, one day at noon, while they were eating their dinner, they heard a strange sound. As it came closer, they realized it was a man singing his death song.

“A rider came to the door and said, ‘Be on the lookout. This man coming, singing, is White Roundhead. He is coming armed to kill every white man that he sees.’ ” White Roundhead had lost his entire lodge of four or five tents to the disease. “Blaming the white people for bringing such a scourge into the country, he was out for revenge.” Susan’s uncle, Swift Bear, took his gun and stepped outside, “firing above the man, who was coming along the edge of the creek bank. Every once in a while, White Roundhead was doubled up with the cramp. He kept on coming with his gun in his hand and bows and arrows strapped to his back, although he was warned not to come any farther. By this time the white men were out with their guns and, as he did not heed the warning, he was shot as he stopped with a cramp again.”

Like White Roundhead, Susan’s Brulé grandmother, Ptesanwiŋ, would also become the sole survivor of her band.83 Like all the other Lakota, her band had fled north as soon as they heard that the cholera was coming. But it was too late—the disease was already among them. “Each night’s camp there were less and less in number, as the people were buried all along the way. Some of them were in the throes of death who were to die anyway so were left behind. By the time they reached the Niobrara River [in northern Nebraska], the whole band had passed away.” Only Ptesanwiŋ and one of her brothers, Brave Eagle, were left alive.

For a while they lived in separate tents on the banks of the river. Winter had come early, making it impossible to travel any farther. “My uncle was busy trailing deer every day in the snow, and brought home the deer. He said to my grandmother, ‘You dry all this meat and make pemmican; it may be hard to find deer when this snow leaves. It is not very far from here to where some of our people are on White River—it is straight north of here. You could not lose your way even if you were to travel alone.’ ”

Ptesanwiŋ worked hard to dry the meat as fast as her brother, Brave Eagle, could bring it in. “One day, she heard a shot as she was cooking breakfast. When she went into my uncle’s tent he had dressed himself in his best clothes, had painted himself for death, and the gun with which he had shot himself was still smoking.”140