Introduction

Let’s Not Do the Time Warp. Yet.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

The eel,” says author James Proesk in his jaw-dropping study of that magnificent beast, the aptly titled Eels, “is not an easy fish to love. It does not have the beauty of the trout or the colors of the sunfish.”

Very much the same thing can be said for The Rocky Horror Show. It is not an easy production to love.

It does not have the beauty of Cabaret or the colors of Cats; it does not have the melody of South Pacific or the style of Chicago.

It is not The Lion King.

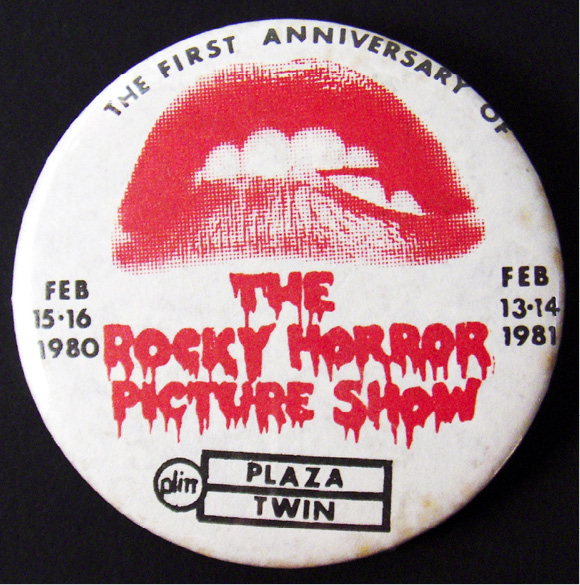

Saw the movie, bought the button: a vintage ‘70s Rocky souvenir.

Author’s collection

It does have laser guns, but only briefly toward the end, and it does have sex, albeit in silhouette. It has humor, of course, and pathos too, and those are good things. And it has songs, which generally are immensely wonderful, but they do need to be handled with care, as singer Maxine Peake reminds us midway through the Eccentronic Research Council’s 2014 festive offering “Black Christ-Mass.”

Peake is bemoaning the average drone’s mandatory indulgence in that most ghastly of rituals, the corporate office Christmas party. It is packed, as always, with groping management, sycophantic secretaries and wage-slave wastrels, and the only reason she’s there is because “The beer is free [and] I’m a cheapskate. . . .”

But even so, “I will never do the time warp again.”

Because it’s astounding how many people you wouldn’t normally want to associate with (Traci from Accounts; the boy with BO from Shipping) think it’s the height of liberated entertainment to do that particular dance.

Badly.

While getting the words wrong.

And mixing up their lefts and their rights, their jumps and their thrusts, their blackness and their void.

It really is rather sad.

But it’s also an indication of just how firmly, and how deeply, The Rocky Horror Show (on stage and screen, on CD and DVD, on every available platform of merchandising possibility) has entrenched itself into our lives. Or at least upon our culture.

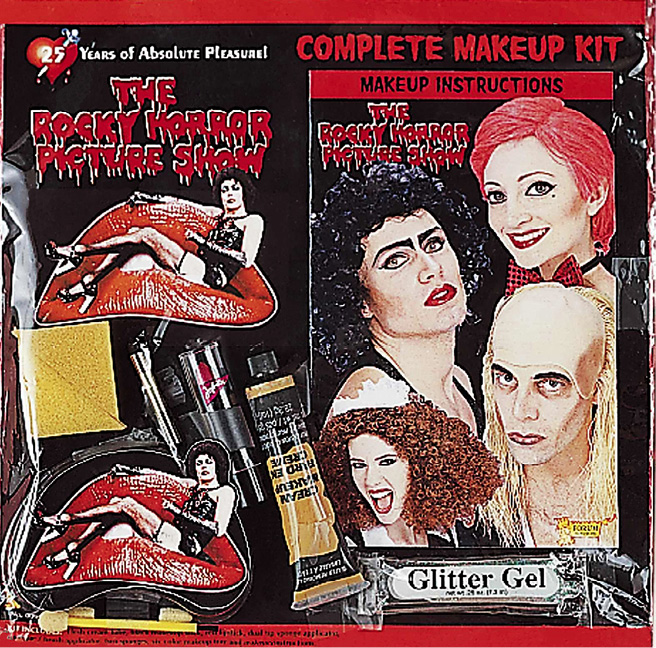

Everything you need for your own Rocky Horror Show: the complete make-up set, including glitter gel.

Author’s collection

Forty-plus years on from its debut in a tiny London theater; four decades, too, from its transition to the silver screen, Rocky Horror stands among the 1970s’ most lasting, and successful, contributions to modern culture.

It has outlived pet rocks, it has outlasted disco.

It has shaken off its Daisy Dukes and pinged Pong back into the Stone Age.

It might even be better known than Randy Mantooth.

None of which is at all shabby for something that many people still regard as a quaint, if kinky, cult.

Not that Rocky Horror itself would be dismayed at that assumption. Indeed, that quaintness and kinkiness might well be among the production’s most lasting attributes.

It does not matter that the imagery within which The Rocky Horror Show so archly cavorts, and the shocks that it once so gamely delivered, have long since been overtaken by events. The Rocky Horror Show lives on despite all the slings and arrows that outrageous time and culture can throw at it, to establish itself as an integral part of every subsequent generation’s cultural DNA . . . and possibly even a factor within the very development of that DNA.

A popular meme circulating the Internet in the sorrowful aftermath of the movie Fifty Shades of Grey depicts the titular Grey himself, with his whips and chains and similar silliness, all decked out for a night of torment . . . and Doctor Frank-N-Furter, Mr. Rocky Horror himself, looking over at him with penis-deflating disdain. And shrugging, simply, “Bitch. Please.”

Because it’s true. No matter how big and bold pop culture may think it has grown in the last four decades, it still hasn’t truly out-rocked Rocky. And it probably never will. Which is why The Rocky Horror Show remains as popular today, among an audience that discovered it for the first time via a Blu-ray disc in 2014, or the following year’s (admittedly overblown) televised anniversary performance, as among those whose initial contact was made before VHS was even available.

Times have changed, society has moved. The Rocky Horror Show has done little of either. But still it played a major role in both the changing and the moving.

In 1973, when Doctor Frank-N-Furter first donned his trademark fishnets, corsets and gorgeous tattoos, and set about building himself the perfect husband, homosexuality had only just been decriminalized in the UK, and was still a long way from there in almost every other country.

And remember, that’s decriminalized, not legalized. Meaning, you could no longer be arrested for expressing your love for a same-sex partner. But you didn’t actually have the right to do so. The idea that one day Frank and Rocky would simply be able to high-tail it down to City Hall, there to tie the marital knot, was so beyond belief that it could not even be imagined.

Likewise, when playwright Richard O’Brien first composed the show’s words and music, his blending of fifties rock ’n’ roll with early seventies glam rock was the ultimate, blinding collision of ancient and modern. Today, glam rock itself is such ancient news that many of its progenitors have already died of old age . . . or at least they soon will. Whereas rock ’n’ roll is now so old that even its revivalists are in the market for walkers.

Nevertheless, every weekend across the world, in those tiny, backstreet movie houses that both time and the multiplex chains forgot to transform into steel and glass monuments to crass crud and consumerism, the night time is the right time.

For that is when the hordes and hounds of Rockydom descend to wallow in a midnight matinee that they’ve seen so many times that they not only know the scripted words, they have written their own script around them.

Plenty of shows, on stage or on film, have encouraged their audience to step into the world that is unfolding on-screen, and dress or act the part of its characters. Attend any sci-fi or comic book convention and they’ll be pouring from the rafters. A Batman here, a She-Hulk there, a dozen different Doctor Whos and the entire crew of Battlestar Galactica.

Mr. Spock!

Seek and you shall find.

But with the exception of the traditional English pantomime, an historically interactive Christmas staple for the juvenile crowd, few (if any) productions have ever encouraged their viewers to so vociferously tear down the so-called fourth wall that divides art and audience, and reassemble the story in their own excitable image. And even panto tends to draw the line at hissing the villain, applauding the hero and shouting “oh no it’s not” when someone on stage says the opposite.

Oh, and warning “behind you” whenever something tries creeping up on the goodies.

The Rocky Horror Show, on the other hand, encourages interaction. Demands, it even; and we speak here of both the Picture Show movie and, in more recent times, the stage show.

Yes, it is true, British audiences looked most askance at the first American tourists to attend the play’s London run in the late 1970s and behave as though they were at the movies. But within just a few short years, the Brits were as abandoned as the visitors, and today a staging cannot be considered even halfway successful unless great swathes of the dialogue are blotted out by the audience playing its own part in the proceedings.

Whether you caught it in New York in 1976, when the Waverly Theatre hosted the cult Anglo oddity’s first-ever stateside midnight matinees; or in Newark, Delaware, in 2012, when the Chapel Street Players mounted a gloriously spirited onstage version, The Rocky Horror [Picture] Show would not be The Rocky Horror [Picture] Show without an auditorium filled by the same distinctive characters that are simultaneously capering around on stage.

Neither does it stop there. In the virtual world of Second Life, at least one troupe of entertainers, Lightning Productions, has added a Rocky Horror Show to their repertoire, recreating every last nuance of the Real Life production in pixelated miniature and drawing in an audience of avatars that likewise gets into the spirit of things. They even type the same dialog as their real-life equivalents!

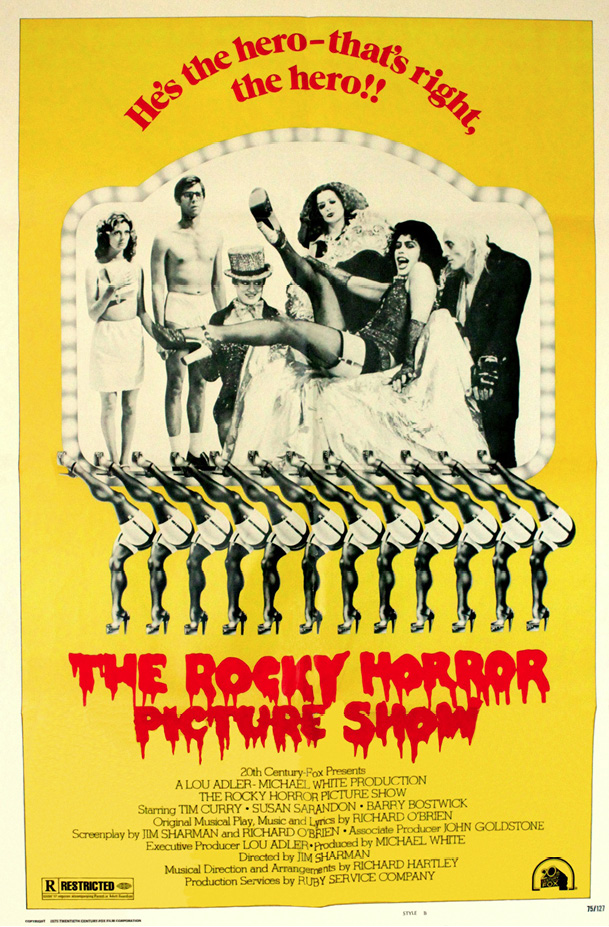

An uncompromising introduction to the movie. “The hero????”

Author’s collection

A world of collectibles has exploded around Rocky Horror. Original cast albums from around the world; books and magazines exploring its universe; bobbleheads and temporary tattoos of all your favorite characters. Action figures. Trading cards. Comic books. Lingerie.

If it can be made, it can be marketed, and though the modern toy store is no stranger today to plastic spin-off tie-ins of every description, from Captain Kirk to the Walking Dead, still there is something almost poetic about finding an alien transvestite, a squeaky-voiced groupie, a cannibalized rocker and a wheelchair-bound professor nestled with the satsuma in the toe of your Christmas stocking.

Poetic as in ever-so-slightly warped.

Warped as in ever-so-gently out of time.

And time, as in just one of the myriad things that stands still when you enter the world of The Rocky Horror Show.

Yet it wasn’t always like this. There was a time, of course there was, when The Rocky Horror Show was not even a figment of creator Richard O’Brien’s imagination. When the songs that we’ve sung with such gusto for what will very soon be half a century had yet to be written; when the lines we can recite so smartly had not yet even been spoken.

A time when Frank-N-Furter was simply an odd way of spelling a particular kind of sausage; when Magenta was just a color and Riff-Raff was an upper-class putdown for the kind of people who . . . well, basically, for the kind of people who weren’t upper class.

A time when the name “Brad” was not automatically associated with that of “Janet.”

An age in which no one did the Time Warp. When the sword of Damocles was just an old fable. And the only light over at the Frankenstein place was the fiery glow of the villagers’ torches, as they turn out to burn out the madman.

But we’ll ring the doorbell anyway, beside the sign that’s marked “the Distant Past,” and we will patiently wait while the misshapen handyman slowly opens the creaking wooden portal; pauses to adjust his hump; and inquires how he might help us.

Maybe he’ll remark on the weather?

Maybe he’ll note that we’re damp.

Maybe he’ll usher us in.

Maybe he’ll offer to take our coats.

Wouldn’t that be astounding?