2

While the Censor’s Away . . .

Writing in his Blood and Glitter autobiography, Jim Sharman, the director of the first Rocky Horror Show, declared that the death of the old regime freed the stage to again indulge in one of its most traditional pursuits, “the early vulgarity that theater had discarded in the pursuit of taste.”

Because that was what the Lord Chamberlain engendered. A preponderance of taste. Good taste. Moral taste. Pusillanimous taste. The theater became a place you could take your granny. Remove him from the landscape, and the old girl would probably have a heart attack before the first curtain even rose . . . as it was rather tastelessly pointed out when the manager of the Royal Court Theatre, George Devine, was felled by a fatal heart attack while performing in his own company’s staging of A Patriot for Me. If it was too much for him, imagine its effect on non-showbiz people!

Thankfully, common sense as opposed to alarmist coincidence was to rule the roost. But still, reflecting on his induction into The Rocky Horror Show from a distance of thirty-two years, actor Rayner Bourton—the original Rocky—told the Birmingham Post newspaper, “You’ve got to remember that it was only four years since censorship had been relaxed in the British theatre. So this was still very shocking. It was virtually soft porn.”

Reg Livermore, who portrayed Doctor Frank-N-Furter in the first Australian production in 1974, just a year after the play’s London opening, continued in a similar vein when interviewed by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2015.

“Rocky Horror was really a grown-ups show. It was for the grown-ups, because it was touching on areas that really hadn’t been investigated in the theatre quite so openly, prior. And so I always think that it was dark and down and dirty, and it had a really sort of seamy edge to it.”

Seamy and shocking. For no matter how many taboos had been broached and breached over those past four years, The Rocky Horror Show was determined, and destined, to shatter many more.

Silhouetted though it might have been, the scenes in which Doctor Frank-N-Furter seduces his guests Brad and Janet offered the audience a glimpse of acts that had never hitherto been witnessed on a British stage, at least beyond the most obscure and forgotten underground productions.

In terms of camp suggestiveness, The Rocky Horror Show gleefully overstepped the boundaries that even English vaudeville and “seaside postcard” humor had established as the furthest reaches of acceptability.

And in terms of style . . . .

The stage had swiftly grown accustomed to the sight of human nakedness—indeed, that was the very first of the old boundaries to crumble.

The Rocky Horror Show showed off something far worse than bare flesh, however. It glorified perversion and corruption, and glamorized fetish, as Roger Baker, authoring the definitive guide to female impersonation in the performing arts, Drag, explained.

“Perhaps [Greta] Garbo’s greatest screen role, Queen Christina [was] a seventeenth century Swedish monarch with a penchant for wearing male attire and almost certainly a lesbian . . . [allowing] the star to fully exploit her ambiguity. Interestingly, Garbo’s appearance in this film is echoed by . . . [Doctor Frank-N-Furter] . . . [who now] made bodices, stockings and suspenders almost de rigueur among heterosexual men.”

The dirty deeds that people do in the privacy of their own boudoirs had always been the province of imagination alone . . . well, that and the smutty postcards and photographs that could be purchased for exorbitant sums from shabby little men in the city’s red-light district.

Now here they were on open display, in one of London’s most venerable theaters.

Not every taboo was shattered at once, but slowly and surely, the old bastions crumbled. By the early 1980s, The Rocky Horror Show appeared very tame indeed when compared to Howard Brenton’s The Romans in Britain (1980), prosecuted for indecency over a scene depicting homosexual rape; in June 2015, audiences at the Royal Opera House in London roundly booed a production of William Tell that included a naked gang-rape scene.

The good old days of Hair seemed very, very far away.

Got My Hair, Got My Naughty Parts

On September 27, 1968, a mere twenty-four hours after the Theatres Act became law, the American hippy musical Hair: A Tribal Love Rock Musical opened at the Shaftesbury Theatre in London.

Produced by impresarios Robert Stigwood and Michael White, it would be, as all the advance promotion made clear, the first live stage show ever to openly present nudity, sexuality, blasphemy and bad language on a British stage. And there was nothing that could be done to prevent it.

With lyrics by James Rado and Gerome Ragni, and music by Galt MacDermot, Hair was the first truly mainstream attempt to place the mores and morals of the then-prevalent hippy generation into a mainstream context—or at least to lay them bare for the consumption of audiences that would include the mainstream.

No longer an underground cult whose secrets could only be misinterpreted and distorted by the “straight” press, the counterculture would be stripped naked by Hair—literally, in one scene.

The story itself was simple: a self-styled tribe of politically active and sexually promiscuous hippies living in New York City find themselves suddenly forced to face up to what really was one of the crucial questions of the day—whether the leader of their little commune, Claude, should drop out, as his friends, peers and musical heroes all seemed to recommend; or “do the right thing” and join the war in Vietnam.

He is certainly conflicted. Having passed his military medical, Claude returns to the tribe and ceremoniously burns his draft card, only for another member of the tribe to reveal that he simply torched his library card. And in the end, Claude does join up, slipping away unseen to do the deed and returning to the tribe only after the worst has happened, a ghost with a single, chilling message: “Like it or not, they got me.”

A cautionary coming-of-age tale, then, a modern fable of youth learning to choose its future path in a world that apparently offered nothing but conflict.

But who remembers, or even cared to pay attention to, the plot? Hair was about the music, the language, the drugs, the sex and the nudity.

Especially the nudity.

No matter that it was merely one single scene, the tribe stalking the stage chanting “beads, flowers, freedom, happiness.” Nor that you needed to be very close to the stage (or at least equipped with some very powerful opera glasses) to catch more than a glimpse of unveiled naughtiness.

In an age when public nakedness was literally confined to art galleries and nudist colonies, even the suggestion that those people up there aren’t wearing a stitch of clothing was enough to enrapture a generation of theatergoers. Particularly in the UK.

In its America homeland, after all, Hair was a long way from being Broadway’s first nude spectacular (for spectacular it was, no matter how brief), even if it was the most pronounced. The most shameless, even.

Historically, earlier honors belonged to 1965’s Marat/Sade, albeit with backs very decorously presented to the audience. Off-Broadway, where the Living Theater and the LaMama Experimental Theatre held sway, tits and ass had been glimpsed (if not glamorized) for years.

The Warhol circus, in which the likes of Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis held such glorious, glamorous (and so sexually ambiguous) sway, was even more colorful, deploying their charms, on- and offstage, to challenge both ingrained attitudes and cultural stereotyping.

But you had to delve deep into the underground, both physically and emotionally, to taste those fruits. Hair was different. Not only was it tits and ass and all other points as well. It was also being rubbed in your face from the heart of American showbiz.

Hair itself started life off-Broadway, debuting in October 1967 at Joseph Papp’s newly opened Public Theater at 425 Lafayette St. (albeit with their back very decorously presented to the audience)—which makes it all the more ironic that, at this stage in the play’s gestation, it actually featured no nudity whatsoever. Zero. There were less songs, too. And more plot.

How dull it must have been.

Still, Hair was an immediate hit, both there and at its next port of call, the Cheetah, a discothèque at 53rd Street and Broadway. As early as the following April, the production was preparing for its debut on the Great White Way, to rock those walls like they’d never been shaken before.

But, first of all, it needed to be revised.

With director Tom O’Horgan coming in from the LaMama Experimental Theater, Hair was completely restyled. All the elements that would bring the newspaper headline writers running were slotted into place. More bad language. More drugs. More sex. And the bare bits.

All of which, had they been Hair’s sole talking points, would have been enough for at least a short-lived hit. But Hair’s creators were sharper than that, just as Richard O’Brien would prove himself to be a few years later. Hair was a musical. Therefore it needed music. And while a good musical features songs that people will like, a great musical features songs that people remember.

A lot of Hair’s early, and most disapproving, press concentrated on songs like “Black Boys” (an ode to a type of candy, albeit one that was gloriously laden with double entendre) and the somewhat less ambiguous “Sodomy” and “Hashish.”

But they were mere interludes alongside the true giants of the score: the opening celebration of the dawning of the age of “Aquarius.” “Ain’t Got No” and “I Got Life”; “Good Morning Starshine” and “Let the Sunshine In.” Those songs are now integral parts of the era’s very lifeblood, in the same fashion as a subsequent generation might look back on “Time Warp,” “Science Fiction Double Feature” and “Over at the Frankenstein Place” as songs that have likewise so transcended their original surroundings that they are now key elements within any self-respecting mid-1970s soundtrack.

The Hair songs that shocked at the time are all but forgotten by the general public today. But almost anyone can strike up the chorus to “Flesh Failures.”

In New York, the public response to Hair was unequivocal. In London, it was all but hysterical. A run of 1,750 performances on Broadway was readily eclipsed by 1,997 in London. True, not everybody who attended each of those performances was delighted by what they saw.

Some were shocked, some were outraged, some were simply bored. Zsa Zsa Gabor went backstage after the London premier and loudly declared “this is not acting.” To which Executive Producer Bertrand Castelli replied, equally loudly, “what do you know about acting?”

All sorts of responses, then. But at least they witnessed it.

Critical response to Hair was just as divided as the audience’s. Among those observers who believed that the theater should be afforded the same opportunities to question, reflect and condemn society that rock and the cinema had long enjoyed, the actual quality of Hair was secondary to its purpose. What mattered was not what it said but what it did, which was shake a stagnant medium to its foundations, and open the door for further explorations.

“Nothing else remotely like it has yet struck the West End,” opined The Times’s Irving Wardle. “Its honesty and passion give it the quality of a true theatrical celebration—the joyous sound of a group of people telling the world exactly what they feel.”

Such opinions were, of course, naturally and ruthlessly countered by those who saw Hair as a brain-damaging barrage of filth and degradation; of gratuitous obscenity and untrammeled disgust.

The clergy clobbered it. The almost-amusingly-named Reverend Michael Botting, Rural Dean of Hammersmith, in west London, organized a petition against the play, describing it as “pornographic and blasphemous,” and adding “I would never encourage masturbation.”

Other public watchdogs, including Britain’s doughtiest antismut campaigners, Mary Whitehouse and Lord Longford, spoke out against Hair’s corrupting influence, doubtless foreseeing a day when all British theater would be conducted in the raw; while the perhaps inappropriately named Society for Individual Freedom railed furiously against the play’s “carefree attitude to drugs, the idea of easy sex, an irresponsible attitude to life, blasphemy and obscenity.” Because individual freedom should never actually be taken to mean freedom.

Many of these same complaints, albeit with alternate wording, would be leveled at The Rocky Horror Show just a few short years later. But there is another reason why Hair should be considered among Frank and company’s nearest and dearest, and it’s not just that line in “Flesh Failures” that promises “I fashion my future on films in space.”

Hair was marketed as the world’s first rock musical, and rock history delights in plucking out the names of the future stars who passed through the ranks of onstage performers and the accompanying band: Sonja Kristina, later to find fame as vocalist with the progressive rock band Curved Air. Alex Harvey, whose Sensational Alex Harvey Band was to become one of the looming decade’s most theatrical groups. Marsha Hunt, a former member of Ike and Tina Turner’s Ikettes, who relocated her singing career to London at the behest of Mick Jagger. Elaine Paige, later to star in Andrew Lloyd Weber’s Cats.

And a bunch of folks of whom we will be hearing a lot more shortly: Richard O’Brien, Tim Curry, Belinda Sinclair, Michael White and Ziggy Byfield in and around the London production; Reg Livermore, Jim Sharman and Graham Matters in Australia’s. Meat Loaf and Kim Milford in the US, Eddie Skoller and Hans Beijer in Europe.

All future inhuman life was there . . . .

O Quel Cul T’as!

English theater critic Kenneth Tynan’s Oh! Calcutta! had absolutely nothing to do with the Indian city of the same name. Rather, with typical English comedic guile, it took its cue, and its amusement, from a schoolboyish mispronunciation of the French phrase quel cul t’as, which translates (very) loosely into “what a lovely ass you have.”

Who said language classes were dull?

Forty-three years old at the time, Tynan was long since established as the enfant terrible of the British arts. His virulent opposition to the Lord Chamberlain’s powers was matched by his staunch support for the Angry Young Men movement that employed the stage as a means of defiling the entrenched British class system in the 1950s; while he was also known, most notoriously of all, as the first person ever to use the word “fuck” on live British television, in 1965.

It was not a gratuitous act, although of course Tynan was well aware of the effect his language would have. Discussing censorship on the BBC, he simply made the trenchant observation that he doubted whether there were “any rational people to whom the word ‘fuck’ would be particularly diabolical, revolting or totally forbidden.” And then followed up by informing the live viewing public that “anything which can be printed or said can also be seen.”

Of course, the incident thrust Tynan to instant notoriety. The aforementioned Mary Whitehouse even wrote a letter to the Queen, recommending that Tynan should “have his bottom spanked”—a fate that several subsequent commentators have noted was an extraordinarily ironic choice of punishment. In his private life, Tynan was a firm advocate of BDSM.

Oh! Calcutta! was not Tynan’s first venture into the world of the playwright, but it would become his most infamous. Overall, it was largely plotless, being an amalgam of scenes written both by Tynan and by a select handful of guest authors, Beatle John Lennon, Samuel Beckett, Edna O’Brien and Sam Shepard among them. And, of course, the producers kept the lid firmly closed on what precisely these scenes might involve.

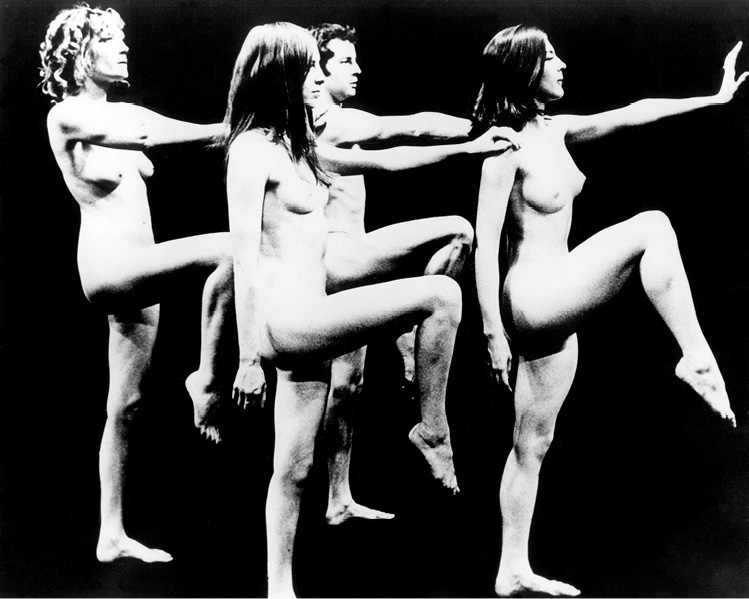

Kenneth Tynan’s Oh! Calcutta! delivered nudity to the stage . . . but rumor had promised even more.

Photofest

Just one rumor was permitted to escape, and an extraordinarily virulent creature it proved to be. As Oh! Calcutta! prepared for its Off-Broadway opening, at the Eden Theatre on June 21, 1969, the word on the street was that it would be the first legitimate stage show ever to feature live sexual intercourse.

And passersby wondered why the lines at the ticket office went on for several blocks.

Of course, the rumor was just that, salacious scuttlebutt designed to put culs on seats. There were no less than six nude scenes positioned strategically throughout the play’s duration, but not one of them was especially explicit.

Success beckoned regardless. On February 17, 1971, Oh! Calcutta! transferred to Broadway’s Belasco Theatre for the first of a total of 1,314 performances. A Broadway revival in 1975 did even better, stripping off for a staggering 5,959 performances to become one of the longest-running revues in American theater history. And the London production was equally successful, although again it was attended by scenes of wild enthusiasm on the one hand and horrified opprobrium on the other.

The Times—at that time still a prestigiously influential publication—condemned Oh! Calcutta!’s London opening thus: “In many ways it is a ghastly show: ill-written, juvenile and attention-seeking.”

The Daily Telegraph was equally unimpressed, although it at least gave the play credit for “teeter[ing] along the borderline between the indecorous and the obscene,” while the Daily Mirror warned, “sadly, it has more corn than porn.”

But from the moment Oh! Calcutta! (another Stigwood-White production, incidentally) made its London debut at the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm on July 27, 1970, the die was cast. Just two months later, on September 30, it transferred to the Royalty Theatre in the theatergoing West End heart of the capital, and it would be another decade before Oh! Calcutta! (by now, it must be said, a strangely tame and innocent period piece) finally pulled its pants up.

The Dirtiest Precursors in Town

With Stigwood and White now firmly established as the enfant terribles of London theater, their next import arrived in May 1971. The Dirtiest Show in Town was the work of songwriters Tom Eyen (words) and Henry Krieger (music), and it did its damnedest to live up to its title, although it was left up to the individual viewer to decide what the dirtiest show itself might be.

The same-sex suggestions and unchastened nudity that made both Hair and Oh! Calcutta! seem almost quaint by comparison, and which culminated in a mass onstage orgy?

Or the Vietnam War, whose ongoing violence represented a very different kind of orgy altogether?

Destined to run for almost eight hundred performances, The Dirtiest Show in Town took the West End by storm. More so than either of its naked predecessors, The Dirtiest Show in Town also worked in the realms of actual political commentary, as opposed to mere sound bite rhetoric.

Of course, it had its problems. The New Scientist was not the only magazine to point out, in its review, that its erotic bits really weren’t that erotic. Or at least “if sex is to be simulated rather than performed, it should hardly be flaunted flaccidly over the footlights.” But the cast impressed: “Madeleine Le Roux was magnificent if you like your women intimidating, and Mary Jennifer Mitchell [one of half a dozen cast members who came over from Broadway with the show] had a voice like a Puerto-Rican Eartha Kitt and the sexiest movements I’ve seen in a long while.”

It had a plot (of sorts) and a purpose. It was uproariously funny. And, in direct theatrical terms, it opened the door through which The Rocky Horror Show—yet another Michael White production—would sashay two years later.

In cultural terms, its portrayal of homosexuality certainly furthered the democratization of sexuality in Britain. But it also cemented the link between sexual deviant and rock star freak that so many past pop idols have toyed with, but which it took the advent of glam rock to perfect, and the birth of The Rocky Horror Show, to perpetuate.

The Dirtiest Show in Town was a wild success. It was not, however, the most accurately titled production. For back at the Chalk Farm Roundhouse, just half a dozen stops up the underground Northern Line, where once Oh! Calcutta! had besmirched the corridors of decency and cleanliness, there awaited another American import that made the dirtiest show look positively pristine.

It was called Pork . . . or, more formally, Andy Warhol’s Pork; and it doesn’t even matter that it never once glanced toward West End respectability or fame. In terms of sewing the final stitch into the theatrical fabric that would cloak the Rocky Horror Show, Pork had no peers.

Oink Oink

“Basically, it was nothing more than a lot of pointless conversation,” assistant director Leee Black Childers says of Pork, the stage show that moved into the Roundhouse in August 1971 and finally proved that, in the new permissive regime of British theater, absolutely anything went.

Pork had it all, every sexual and chemical “-ology” that the human mind can conceive of, and more besides. And it sprang from one single source, the box of cassette tapes that Andy Warhol had accumulated over the past three years, documenting every telephone conversation that he and actress Brigid Polk had ever enjoyed.

Warhol’s vision was of a twenty-nine-act, two-hundred-hour commentary on a society in which people have forgotten how to listen to each other, because they’re too busy taking drugs and having sex. Preferably, dirty, deviant sex. Director Anthony Ingrassia then edited this sprawling Behemoth down to two acts and a mere two hours. But the gist of the play remained the same.

The Pork team, cast from the fringes of both Warhol’s circus and Ingrassia’s past work on the New York experimental scene, arrived in London in June for six weeks of rehearsal; time enough to get the lay of the land, while slowly comprehending just how controversial their play was going to be.

Just weeks earlier, screenings of Warhol’s latest movie, Women In Revolt, had been raided by Scotland Yard’s antiobscenity squad. Now its star, Geri Miller, was in the UK with Pork, and that alone was sufficient to set the moral watchdogs howling against Pork.

Nightly, protestors descended on the Roundhouse, with one group so determined to disrupt the performance that it block-booked an entire row of seats and slow-clapped through every scene that dismayed its members. Which was most of them.

“We got reviews like you wouldn’t believe,” actor Wayne (now Jayne) County recalled. “There’d be the really intelligent reviews about Andy’s art and the sociopolitical side of it all, and we’d just say ‘what is he going on about?’ Then there’d be The Sun saying ‘stop these perverts!’”

The Times described Pork as “a witless, invertebrate, mind-numbing farrago”; the News of the World reckoned that it made Oh! Calcutta! look like a vicar’s tea party. County continued, “then there was someone who said ‘Pork is nothing but a pigsty. Pork is nothing but nymphomaniacs, whores and prostitutes running around naked on stage.’

“The next night we were packed to the rafters!”

No recordings exist, no footage, no documents beyond photographs and memories, so we can probably agree that Pork was a lot of the things that its detractors claimed it to be. But it was something else, too. It was a mad sexual extravaganza that not only had no precedent on the British stage, it had none in British society, either.

No sexual act was out of reach. Indeed, by the time the evening’s performance was over, acts that had once seemed unimaginable beneath the spotlight were looking positively old-fashioned and, dare one say it, boring. People douched onstage. They held orgies as unconcernedly as other people might queue for the bathroom. They pooped on one another. Even open-minded eyes left the show reeling. Bigots more or less self-combusted.

The factor that separated Pork from those other shows was in its approach to its subject matter. Hair and Oh! Calcutta! shocked because that, in part, was what they were supposed to do. They looked at contemporary societal attitudes and neuroses and then calculatedly set out to disrupt them.

Pork (and, to a lesser degree, The Dirtiest Show In Town), on the other hand, was hatched within an environment where no such attitudes existed. It approached sex (and drugs and, yes, rock ’n’ roll) not as a reaction against existing conventions, but as a lifestyle in and of itself. It was not “liberated,” because it did not believe it had anything to be liberated from.

It simply existed, positing a world in which its cast’s behavior, no matter how abhorrent and depraved it might seem to a “normal” human being, was perfectly normal to them.

Almost as if they were aliens. Invaders from another world. Science fiction sex fiends come to wreak unimaginable perversions on the pale, innocent flesh of this planet’s youth.

The world’s first Triple X B-movie was about to be born.