3

Did the Earth Stand Still for You Too, Dear?

Yet Frankie, Riff-Raff and Magenta were not the first sexy space invaders.

Remember Captain James T. Kirk of the Starship Enterprise, as he rocketed around on his five-year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, and to boldly grope every humanoid beauty that happened to catch his fancy?

Yes, he could dress it up as nicely as he liked, with all that “on Earth, we call this kissing” business. But put yourself in his paramours’ place. They were about to be felt up by an alien being.

Neither was Kirk alone in his interspecific philandering. Claude, the oh-so-human protagonist of Hair, was originally written and performed as a space alien (albeit one born in Flushing, New York, of Polish descent), here on Earth to pursue his ambition of becoming a movie director but finding himself instead about to be drafted.

It doesn’t make any difference whatsoever to the development of the story; in fact, Claude prefers to believe that he’s from Manchester, England, and not one of the production’s earliest reviews even seem to be aware of the fact that Claude hopped in from outer space.

Not the New York Times, not the New York Post. Not the Wall Street Journal (although its opening night review at least commented on Claude’s “lovely blond mane”); nor did the Village Voice. Not one review appears to have found it necessary to remark that Claude was not of this world. So, when Hair switched to Broadway and its hero switched species, nobody noticed that, either.

Still, the thought was there.

The final piece in the pre-Rocky jigsaw, then, at least so far as sexy spacemen go, was David Bowie, and in particular, his 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, a loosely conceptual piece in which a rock ’n’ rolling alien falls to Earth around the same time as humankind learns that the planet has just five years left to live.

Riding a message of hope that goes at least some way toward soothing that shock, Ziggy becomes the biggest star the world has ever seen, only to discover that fame is a double-edged sword. No matter how much he tries to help his audience, they demand more and more, until finally Ziggy steps, or falls, away. The final song in the cycle is titled “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide,” and we assume that was Ziggy’s fate.

It was a brilliant piece of work, as cinematic as any simple long-playing record could be, and all the more surprising for where it came from. Bowie, after all, had spent much of the previous decade as an itinerant wanderer of no especially permanent musical convictions.

Often described today as a rock ’n’ roll chameleon, changing his face like others change their underwear, he was actually more akin to a dilettante butterfly, drifting from musical fashion to musical fashion, in search of the one that he could most successfully stick to.

Four albums released between 1967 and 1971 had already introduced a tiny fan club to Bowie the vaudevillian, Bowie the folkie, Bowie the heavy metal monster and Bowie the sensitive singer-songwriter. Each one surfed the most recently fashionable musical zeitgeist; each one essentially went nowhere. So when a new craze began to peek over the parapet, in the form of the glam-rock movement, it was more or less inevitable that Bowie would be trying that next.

Ramming in the Glamming

The story of glam rock is the story of unfettered experimentation, uninhibited libido and unrelenting curiosity, all set to a pounding, mid-coital beat.

Throughout its lifetime, a period that history now measures between 1971 and 1975, it had just three fixations: sex, in as many varieties as it could be found; science fiction, with as kitsch an angle as it could be schemed; and a yearning nostalgia for the 1950s, when everything was simpler and tasted better, too. The same ingredients that The Rocky Horror Show seized upon, at much the same time as well.

It was Marc Bolan of T. (née Tyrannosaurus) Rex who set the glitter ball rolling in the first place, transitioning from, again, a longtime aspirant to a superstar demigod with little more than an ear for jagged guitar riffs, an eye for sequin and satin, and an unimpeachable understanding of what rock music ought to be . . . sexy, potent, youthful and fun. All bound up into one glorious and utterly irresistible package.

Over the years, a few grumpy critics have suggested that glam rock, or a close approximation thereof, would have happened anyway; that Bolan was simply the lucky first contestant. And it’s true that there were antecedents galore.

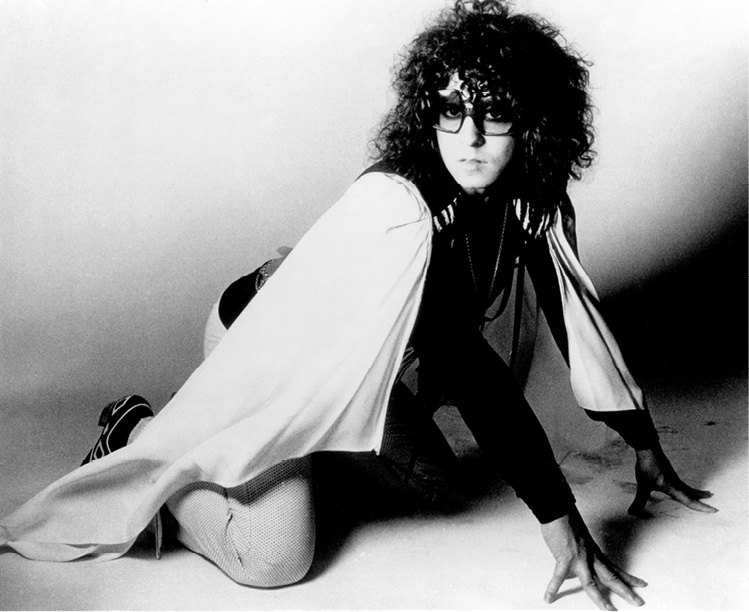

Marc Bolan, the effervescent front man for glam rock icons T. Rex.

Photofest

Flamboyant fifties rocker Little Richard was glam fifteen years before Bolan even dreamed of donning glitter. The Rolling Stones dressed up as women (for their “Have You Seen Your Mother” promo film) while Marc was still wearing short hair. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins took the stage dragged up as a ghoul.

The Kinks, whose name speaks volumes if you want to look at it that way, sang of transvestites, and there’s a small forest’s worth of tabloid newsprint that insists that the early Beatles, Stones and Pretty Things were naught but a bunch of lady-boy sissies.

It’s true. If glam had been purely a visual and lyrical confection, that would be an end to it.

But it was also a blending of a variety of other cultural currents as well.

The extravagances of Hair’s psychedelic era, though dead and buried as a musical force by the end of 1969, clung on as a sartorial statement into the new decade, and they continued evolving as well.

But the velvets, lace and dandyism of the original London underground had shifted their focus now, away from the disgraced statements of political and social liberation that fired the revolutionaries of the late 1960s, toward sexual liberation as well, an awareness that the moral climes that had survived unchanged through the twentieth-century-so-far were finally getting the facelift they required.

“Mime was one of the key breakthrough movements at that time,” says Michael DesBarres, a star of The Dirtiest Show in Town, and one of the young actors and artists who called the London arts scene home at that time. “And Lindsay Kemp was a huge influence on everyone who was taking notice of everything. That silent exhibition with white face was very intoxicating, because it looked so removed, and it looked so glamorous, and you didn’t have to learn anything. You just had to move.”

The young David Bowie had already worked with Kemp, onstage and on television; had even opened for Bolan’s Tyrannosaurus Rex as a mime act; and he and Bolan were friends. For people like them, and many more besides, home was a world of feathers and satin, a nation whose boundaries were drawn between the Speakeasy nightclub and Biba’s boutique on Kensington Church Street, and which was populated by dropouts, revolutionaries, drama students, rock ’n’ rollers. By all things bright and beautiful, with the balls to be a butterfly.

It was a world, DesBarres continues, “where hashish was smoked and clothes were exchanged between sexes. And there was a very specific bunch of guys who were androgynous, and who were into that debauchery, but—and this is where a lot of people miss the point—they weren’t gay. A lot of people talking and writing about this period focus on boys fucking boys, when in fact it was boys who looked like girls fucking girls.”

Homosexuality did exist in this world, and so did bisexuality (“of course it did,” laughs DesBarres. “It was another word for Quaaludes”). But they were merely single acts within the entire play. Hedonism in all its guises was what these searchers truly sought, and just as Rimbaud employed it as the battering ram to rewrite the poetry of a century before, so now the point was to use it to completely rewrite rock ’n ’roll.

Bolan moved with these people; he was moved by them; and they were moved by him in return. First within his own circle, and then around the world. He was not the first person to play with all of the different elements that rock historians can cite as his antecedents. But he was the first to take all of those elements—sexual ambiguity, sartorial sensuality, literary art and theatrical cinema—and blend them into a cohesive whole.

Musically, glam might well have been little more than an hysterical reaction to the musical and cultural stagnation of the previous couple of years. But it was also a social revolution, a cultural uprising, an erotic explosion and a moral reassessment. Glam rock was Sex Rock, Art Rock, Poetry Rock, Mime Rock, West End Musical Rock, Edgy Art-house Cinema Rock, and more, and none of those components would be the same again.

So far, so intellectual. But glam was also a commercial force, and one that was destined to reign supreme for close to half a decade, which it certainly couldn’t have done if the only people it appealed to were a bunch of self-styled deviants who liked wearing each other’s clothes. And that is where Bolan truly stepped out alone.

Music had grown serious. Back in the early–mid-sixties, an artist was only ever as good as his, her or their last single. That had changed over the last few years; albums had risen up as the art form to adore, and singles fell from grace. Bolan restored them to prominence; more than that, he reawakened the 45 as the purest art form of all. If you could not say what you needed to say in three minutes, then maybe you should just keep your mouth shut. Letting rip in a surge of sequins and sex, it took him one hit to make it, one hit to consolidate it, and after that, he could do what he wanted.

The genre that Bolan so effortlessly created was essentially one of pure narcissism, nothing more or less. Other pop stars seemed larger than life; the glam-rock pack was even larger than that. Aided by British television’s recent conversion to color, and a massive resurgence in the power and sales of the pinup press, it revolved around looking good, sounding good and being good. The biggest glam stars could do all three.

It meant projecting glamour, not as the nebulous property of some Hollywood screen goddess (although that was a part of it), but as something tangible, something that could be encapsulated in a word, in a gesture, in a chord. And most important of all, something that could be emulated: Monroe’s beauty spot, Harlow’s platinum blondness, Jagger’s pout, Lennon’s sneer. Catch the eye, and nail it down.

The magic was delivered on every level. Even a simple photograph captured it, and that in itself was a breakthrough.

Pop music had often been criticized for being a poor second to the packaging, but in the past, only a privileged few could actually get away with it. Glam liberated the halt, the lame, the ugly and the hopeless, as if a sprinkling of glitter and a pair of platform boots were all that were required to bring a hint of glamour to the most disparate of careers.

When the Strawbs went on television with rouged cheekbones, they were no longer folkies, they were glitterfolkies. When Edgar and Johnny Winter smothered themselves in rhinestones, they were no longer bluesmen, they were glitterbluesmen.

Jenny Haan packed a suitcase of costumes that transformed Babe Ruth’s prog into glamprog.

There was glittersoul (Labelle, silver spaceship divas asking impolite questions in French), glittertrash (the New York Dolls), glitterfunk from George Clinton’s family tree. To both the saddest cynic and the most dedicated progenitor, glam functioned on a level so transparent that you could indulge it to whatever level you liked: lifestyle, image, or just a pair of platform boots to beautify an otherwise rotting carcass.

Bryan Ferry was already an aspiring nightclub crooner when he hooked up with the musicians who became Roxy Music and, for at least a few years, held his smoother instincts at bay with a sound that redefined art rock for the ages—and, as a fascinating sideline, made a star out of Brian Eno, an electronics whiz whose greatest visual hook was that he was a dead ringer for Richard O’Brien! So much so, O’Brien later laughed, that a mutual friend delighted in introducing the pair, just to see what would happen. As Roxy’s fame took off during 1972 and 1973, O’Brien grew wearily familiar with being mistaken for Eno on the street, so closely did their hairstyles, cheekbones and body shape collide. He hoped, as his own star rose, that Eno suffered the same misidentification.

Rod Stewart was another sixties club veteran for whom the spangles had no other purpose than to keep our minds off the fact that it had been people like Rod who made glam rock so necessary in the first place. One day, Stewart visited the rented apartment where the Pork crew were living while they were in London. Apparently, the first sight to greet his eyes was a naked woman bending over and staring at him from between her own legs. The visitor promptly fled.

And that was glam rock, a movement so garish that it might all have been quite horrifying if the mood of the times had been a little less flippant.

But it was a flippant time. Even the darkest of fantasies could be defused without the slightest effort. It was only later that rock historians began to draw the dividing line between Good and Bad Clean Fun, and even then it was clear that the process was little more than a safety valve by which an ego could justify appreciating something so ultimately facile as glam rock.

But glam was not facile, any more than it was ultimately rock. Glam was an attitude, a feeling, a shift in societal tempo and an upsurge in cultural awareness.

It let you know that it was okay to be strange, or different, or weird. It taught you that sexuality is not defined by who you fuck, but by why you fuck them.

And it lined up its targets with military precision.

The crushing conformity of class and education (it is no coincidence that one of the biggest cult movies of the immediately pre-glam era was Lindsay Anderson’s If . . . ).

The dull repetition of work and suburbia (punk rock, the musical movement that followed glam with such indecent haste, was simply the sound of glam’s audience showing what they’d learned).

The ponderous burden of tradition and history . . .

And it picked them off one by one.

What more could any generation have asked for?

Well . . . .

In later years, Bowie’s fan club would argue that The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, their hero’s breakthrough album, was germinating long before glam rock first dragged the frilly panties from its big sister’s closet. And maybe it had. But Bowie himself didn’t care.

He may have been a comparative Johnny-come-lately to the glam-rock party, but he brought more than a bottle of Blue Nun and a tray of warmed-up vol-au-vents.

He bought sex and sexuality. He rode that six-month-old newspaper article in which he’d admitted he was gay (or at least bisexual . . . “girls are smashing, too,” the happily married father simpered); he raided the wardrobe and a cosmetics tray that the cast of Pork had left behind; and he invented the ultimate pop star.

Or at least the next best thing to one.

For a while around Christmas, 1972, the UK music papers were full of rumors that Bowie was preparing a Ziggy Stardust stage show, a bona fide theatrical presentation whose plot (and some new songs) would plug the gaps between those on the existing album, and which would be debuting at a West End theater very soon.

It didn’t happen. As with so many of the tales that sprang up around Bowie and his mercurial creation at this time (and everlastingly since then, too), it was a fleeting notion, a vague idea, an ambition that he voiced in a moment of playfulness, knowing full well that it would be absorbed into the mythology that already surrounded him.

But just because Ziggy Stardust wasn’t yet ready to fall to Earth, that didn’t mean that other spacemen were so shy. And light years from here, on the planet of Transexual, in the galaxy of Transylvania, on the moon-drenched shores of that androgynous planet, wide, Kohl-drenched eyes gazed down upon this planet and laid their evil plans.