It was on June 16, 1973, in a tiny, sixty-three-seat theater on Lower George Street, in west London’s once-fashionable Chelsea, that the world caught its first glimpse of the madness that would become The Rocky Horror Show. And of the madness that would reinvent British theater . . . and, in particular, British rock-musical theater . . . for a still reasonably new decade.

Chelsea itself had fallen fast since it was one of the focal points of the city’s Swinging London set in the mid-late 1960s. although it really wasn’t that precipitous a plunge.

Pleasantly poised on the north bank of the River Thames, Chelsea had forever been torn between an industrial heritage and Bohemian chic, between affluent housing and tumbledown streets.

Take one turn off the arterial King’s Road, and you found yourself on Cheyne Walk, luxurious home to the rich and powerful ever since Chelsea was a village, and the Raw Silk Company cultivated mulberry and silkworms there. Take another, and terrace upon terrace of dilapidated Georgian townhouses had long since been converted into single-floor apartments, largely rented to low-income families.

David Bowie lived in Chelsea, and so did Mick Jagger. But the Rolling Stone’s latter-day wealth had not always been his to blithely command. A few years before he took up residence on Cheyne Walk, Jagger and his bandmates were crammed into an unheated cold water flat just a few hundred yards away.

For that was the dichotomy of Chelsea. Face in one direction, and you could gag on the stench of the massive Lots Road power station, built to provide electricity for the London Underground subway system. Face in the other, and you would inhale the heady bouquet of incense and perfume as it wafted from what had once been the trendiest boutiques in the city.

Granny Takes a Trip and the Sweet Shop held Swinging London in their thrall in the sixties, and a vestige of that old glory clung still to them in the early 1970s. But the times were changing, and the tides of fashion, too. Just a dog’s-legged corner away from Granny’s, with its velvet loon pants and electric satin scoop-neck T-shirts, a new boutique had opened up—Let It Rock, catering to the city’s Teddy Boy populace, fifties rock ’n’ roll fanatics whose fashions were making a comeback now.

Not only their fashions, either. Their music, too, was picking up speed once more. Half-forgotten icons from the dawn of the rock age were making regular pilgrimages across the Atlantic to perform before an audience that still worshipped in their footsteps—Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley; and new bands were rising in their wake, dressing the part and sounding the same.

Glam rock itself lifted as much from the past as it did from any contemporary currents. David Bowie’s live set included two Chuck Berry oldies, “Around and Around” and “Almost Gone.” Marc Bolan and T. Rex were confirmed Eddie Cochran nuts and rewired his “Summertime Blues” as an anthem for the new generation.

Imminent hitmakers Mud, Wizzard and Showaddywaddy scratched their sound from the Let It Rock jukebox, and their dress sense off the same store’s racks. Alvin Stardust reinvented Gene Vincent’s lizard leather look, and developed a stance straight out of the Bluejean Bopper handbook. And Gary Glitter was little more than a pulse-pounding barrage of fifties drums and guitar licks. His first hit, still the soundtrack to sports events all across America, was called “Rock and Roll.”

It wasn’t a purely British phenomenon. In the US, the unabashed nostalgia of American Graffiti and Grease was looming. Sha Na Na, a straight-ahead fifties tribute act, played the Woodstock Festival; Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids were rising fast. And though it hurt a lot of trendy journalists to admit as much, if the musical purity of that earlier age had any modern, early-seventies equivalent, it was in the posturing and pounding of the British glitter kids, recalibrating the sounds they had imbibed in their teens and then sending them out to play once again.

One of those kids was named Richard O’Brien.

The Man Who Would Be Eddie

Richard Timothy Smith was born in Cheltenham, England, on March 25, 1942, growing up amid the deprivation of the World War II years, in a town that had more than its fair share of conflict.

Factories both in town and in nearby Gloucester, six miles away, were a regular target for the German bombers, and even when there were no raids in sight, the air hung thick with the stench of burned paraffin, from the clouds of smoke that were sent up into the sky to obscure the targets from the foe.

Cheltenham suffered its worst air raid in December 1940, when twenty-three people were killed in one night; by the time O’Brien was born, the German offensive was all but over, and the air raid sirens were a thing of the past. Still, just ten days after his birth, the enemy bombed Brockworth aerodrome, home to the Gloster Aircraft Company, and Cheltenham remained on a war footing for the next three years. Signs of the conflict were everywhere, from the vast Emergency Water Tank that was embedded in the ground in Promenade Gardens, to the roar of the American bombers operating out of the USAAF bases that littered the countryside, and on to the rationing that offered every family barely enough food to live on, and which only grew worse once the war was over.

In 1951, however, the family put all this behind them, emigrating to New Zealand to take up occupancy of a farm in Taraunga, on the outskirts of Hamilton.

O’Brien (he adopted his grandmother’s maiden name once he determined he wanted to pursue a career in acting) was raised in an environment that he later described as akin to the American Midwest. Culturally a few decades behind the rest of the Western world, and politically reveling in the thrall of isolationist carelessness, New Zealand’s attitude essentially decreed that the rest of the planet could do what it pleased. Life in Taraunga would go on as it always had.

So far as entertainment went, things were a little better than that sounds. At least there were two movie houses in Hamilton, one for hot new releases and one for more culty fare. But there was very little else. Although Taraunga is now ranked among New Zealand’s six largest cities, possessed of the country’s largest port, in the fifties (and Hamilton is one of the top three), back then it was little more than a small town, all farmland, dust and locally owned businesses.

Still, the movie houses did their best to show what life was like across the ocean—or at least what life might be like.

To viewers elsewhere around the world, American cinema of the 1950s was gloriously glamorous, ineffably romantic. Even the grimmest movie depicted lifestyles and livelihoods far removed from anything that their overseas audience could ever have imagined, but which they were more than willing to accept were the American norm.

The biggest cars with the biggest fins, the biggest homes with the biggest swimming pools. Forget the Pentagon, politics and brainwashing spooks. The biggest propaganda victory of the age was won by Hollywood.

Land of the brave, home of the huge. Catch an American crime movie, and the baddies carried the biggest guns—at least until the good guys arrived, because theirs were even bigger. Watch a horror flick and you’d see the biggest monsters. Watch a teenage glamor romp and the girls had the biggest breasts, and blew the biggest bubbles with their gum.

Everything was outsized, beautiful and brash, and the kids who flooded the movie houses in those years before television and rock ’n’ roll arrived had found the icons that would sustain them through their teens. Marlon Brando and Jimmy Dean, Jayne Mansfield and Marilyn Monroe. Talking to journalist Patricia Morrisroe more than twenty years later, O’Brien’s very language still clung to the flavor of those 1950s redoubts.

He went to the movies a lot, day upon day spent at the Embassy Theatre in Hamilton, and when he started working, where better than at the hairdresser’s located next door to the theatre? “What else can you do in a small-town parochial society?” he asked Morrisroe. “You see films, you play sports. If you were a bit of a punk like me, you hung out in street corners and tried to pick up girls. . . .”

“A bit of a punk.” Before the late 1970s came along to redefine that simple word, you knew exactly what O’Brien was talking about. A “punk” was a wild kid, smarmy and street-smart. Again, Marlon Brando, Jimmy Dean. Mouthing off to his elders in thought, word and deed. In New Zealand, and across the water in Australia too, they called them bodgies, and the teenage O’Brien was unflinchingly one of them.

An old copy of the Sydney Morning Herald, dated just a few months before O’Brien arrived in New Zealand, paints the picture, not only of the bodgies “growing their hair long and getting around in satin shirts,” but also of the widgies, their female counterpart, “cutting their hair short and wearing jeans.”

Nice boys didn’t like widgies. Bad boys, bodgies, couldn’t get enough of them. Twenty years after O’Brien arrived in New Zealand, and ten years after he went back to England, he would create one of the modern world’s most majestically archetypal bodgies, a denim-clad rocker named Eddie, and pair him with the ultimate widgie, Columbia.

“Eddie” was (and remains) a great bodgie name.

O’Brien’s 1950s were spent soaking up the influences that were eking over from the US and the UK, and the early 1960s too. He heard Elvis, and learned to dance like him, and then to dance unlike him too. He heard Buddy, and taught himself to sing like him, a tremulous voice that was really no voice at all, with Holly’s trademark hiccup supplanted by just a soupçon of deadpan evil. He heard the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and he realized that New Zealand simply wasn’t enough any longer.

O’Brien returned to England in 1964. At first, he moved in with his grandparents in Cheltenham, but quickly he made his way the ninety or so miles to London, one more provincial kid heeding the swinging city’s siren call.

He originally intended to stay in England for just a year; at least that was what he had budgeted for it. That determination ended when he ran out of money a lot earlier than he expected, but he was not ready to go home so soon. Instead, he cashed in his return ticket and blew through that windfall in a matter of weeks. Clearly, he needed to make fresh plans.

Escaping from New Zealand notwithstanding, O’Brien was undecided what he wanted to do with his life. He just knew that London would be a far easier place in which to make up his mind than Taraunga.

He did a spell in hairdressing, another driving trucks, and another working the night shift at Henry Telfer’s meat pie factory on Lille Road in Fulham. Always, however, he kept his ear to the ground, searching for something else.

He found it with the realization that the movie and television studios, of which Britain then had a considerable number, were forever on the lookout for stuntmen; and, in particular, stuntmen who knew how to ride, and (perhaps more importantly) fall off, horses.

Life on his parents’ farm, where he learned to ride bareback at the age of twelve, had taught O’Brien the basics of the art; a few refresher lessons brought him up to speed, and sharp-eyed observers may or may not spot O’Brien taking a tumble in such movies as Carry On Cowboy, a 1965 western send-up featuring one of Britain’s best-loved comedy gangs; The Fighting Prince of Donegal, a barely remembered Disney flick from 1966; and Peter Sellers’s 1967 James Bond spoof Casino Royale (based on an original James Bond novel, but not considered a part of the overall franchise of films until its 2006 remake).

There were others, too, but O’Brien was tiring of the stunt life, and the people who populated it, the ones who would walk into an audition, or meet you in the pub one night, and just murmur with vague but meaningful machismo, “a funny thing happened the other day. I broke my leg.”

Aptly named on the banks of the River Thames: the Mermaid Theatre.

© Daily Mail/Rex/Alamy Stock Photo

Enrolling at the Actors Workshop, he began attending auditions, not as a potential stuntman but as a prospective regular cast member, and, at Christmas 1968, he found himself working as a runner and an understudy in the legendary designer Sean Kenny’s production of Gulliver’s Travels at the Mermaid Theatre.

Starring Manfred Mann pop star Mike D’Abo as Gulliver, it was one of the all-time great recountings of the tale. A full forty-two years later, the Guardian’s Philip French recalled, “I’ve since seen a number of adaptations [of Gulliver’s Travels], but only one of real worth: the version Sean Kenny, who died tragically young in 1973 aged 40, co-wrote, co-directed and designed at Bernard Miles’s Mermaid theatre. It was a remarkable imaginative and intellectual achievement, taking in all four books (so kids got to hear about Laputa, Glubbdubdrib, the Houyhnhnms and the Yahoos, as well as Lilliput) and including a sea sequence shot in a pond on Hampstead Heath.”

Gulliver’s Travels was only intended for a short run through the Christmas season, but it was to prove an immensely influential one for O’Brien. Not only was he working with one of the most gifted designers in British theater, but he also became friends with one of its most talented songwriters and playwrights, Lionel Bart.

In 1999, Bart recalled their introduction for The Independent newspaper.

“I went to see [Gulliver’s Travels] with my agent, and that is the first time I cast eyes . . . on Richard. He was in the company along with some worthies like William Rushton and Mike D’Abo. The whole thing was conceived as an ensemble piece where every actor played . . . six or seven roles. He was a little whirling dervish. At the time Richard was slightly thin on top with long straggly hair down to his shoulders. I went backstage afterwards for a drink with the cast, and I thought, ‘Hello, this is a character, this person is different.’ He made an impression.”

Years later, in 2012, O’Brien would star as Fagin in a New Zealand revival of Bart’s award-winning Oliver. For now, with the Mermaid season over, O’Brien returned to the pie factory et al. But nine months later, when the producers of Hair commenced casting for the musical’s first touring production in 1969, O’Brien went along.

He was accepted, alongside two other young thespians who would go on to play a major role in his immediate future, actress Kimi Wong, who became O’Brien’s first wife on December 4, 1971; and Tim Curry, who became his first Doctor Frank-N-Furter.

O’Brien’s role in Hair was minimal, more or less a bit part that saw him playing a leprotic apostle. But it was satisfying enough that, having spent nine months on the road with the National Company, he then embraced a further nine on the London stage.

Christ—the Musicals

Two years later, now the father of an infant son named Linus, O’Brien was still struggling to break out of the crowd scenes as he auditioned for and was absorbed into the chorus of the religious rock musical Jesus Christ Superstar.

The work of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, Jesus Christ Superstar was the latest, and possibly the greatest (or at least the least grating) of what amounted to a veritable plague of biblically themed musicals, all of which turned up in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Rice and Webber had already scored a major hit with their first-ever collaboration, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat; while the genre itself dated even further back, to A Man Dies, an early sixties Jesus in Jeans production schemed by a west country English priest with no real musical background at all, the Reverend Ernest Marvin, and actor Ewan Martin.

A huge hit at the time, it was unquestionably an influence on all that was to follow, although decades later, hindsight cannot help but wonder why. The late 1960s were not an especially religious time, after all—or, if they was, it was the alternative religions that had the upper hand. Hair was still heralding the Age of Aquarius; Black Sabbath were promulgating what their opponents referred to as Satanic worship; George Harrison was investigating Eastern mysticism. Open the newspapers and you were more likely to read of the antics of Wiccan figureheads Alex and Maxine Sanders, than you were the exploits of the JC gang.

So, a biblical backlash? Maybe, although religious groups found plenty to complain about in these new plays’ portrayals of Christ and Co. Jesus Christ Superstar, especially, raised the ire of the faithful after Tim Rice told Newsweek, in 1970, “We don’t see Christ as God but simply the right man at the right time at the right place.”

Their outrage was scarcely likely to dent the play’s popularity, however, and neither were a slew of other assaults. The BBC briefly banned the album on grounds of blasphemy. although it swiftly recanted, while the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith insisted that a “sharp and vivid emphasis on a Jewish mob’s demand to kill Jesus can feed into the kind of disparagement of Jews and Judaism which has always nurtured anti-Jewish prejudice and bigotry.”

All, however, were whistling in the wind. For not only did Jesus Christ Superstar have great press, it also had a host of good songs, catchy songs, easy-to-remember songs. Like the title theme, so readily adapted to the juvenile sense of humor.

There was this soccer player; long-haired, flash and so flamboyant that either you loved him or you hated him. And if you hated him, you sang these words:

“Georgie Best, Superstar

“Walks like a woman and he wears a bra.”

He didn’t and he didn’t. But it was an amusing ditty, regardless. And maybe, just maybe, it tapped into that same swirling undercurrent of curiosity and experimentation that other, older, minds were pursuing to more artistic ends?

“Doctor Frank-N-Furter, Superstar. . . .”

Jesus Christ Superstar opened at the Palace Theatre in London on August 9, 1972. Fresh from Hair, Paul Nicholas played the title role; David Bowie’s ex-girlfriend Dana Gillespie was Mary Magdalene; elsewhere around the world that same year, future ABBA star Agnetha Fältskog appeared in the Swedish version, and the Australian take featured one Reg Livermore. A name that we will encounter again.

O’Brien’s efforts were not wholly confined to the chorus, although that is where history best remembers him, an inaudible voice amid the twenty-three-strong chorus of Apostles and ensemble. He was also the understudy for the part of King Herod, as played by Paul Jabara, and when the American’s three-month contract expired in October 1972, it was with an eye for brightening up that role that O’Brien hatched a most peculiar notion. That the infanticidal Herod should be portrayed as Elvis Presley.

It was not the most widely applauded idea that O’Brien has ever had. Up the chain of command went his notion, from director Jim Sharman to writers Rice and Webber, and on to the producers whose whims controlled both the play’s direction and its purse strings.

And down again came their response. Elvis was out. But he could tap-dance, if he wanted to.

According to legend, O’Brien was so disappointed that he quit the religious rock biz on the spot.

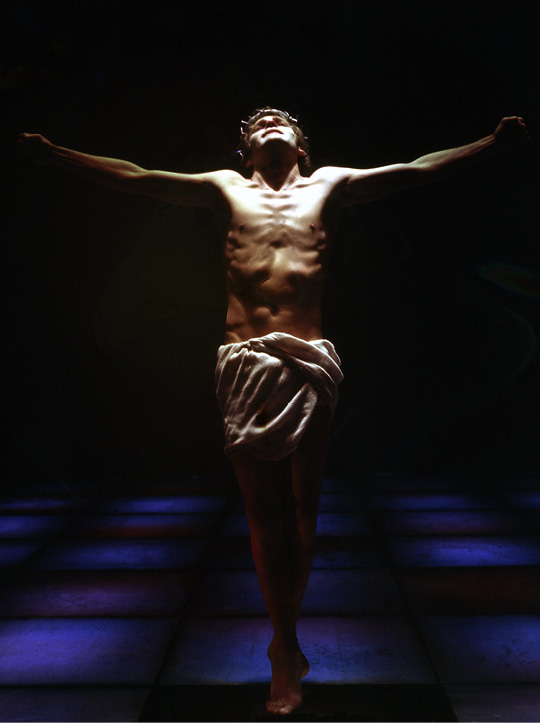

Paul Nicholas in Jim Sharman’s London production of Jesus Christ Superstar.

© Allan Warren/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons

Again, he was officially unemployed, but this time, he was scarcely downhearted. Rather, it was a plight that he resolved to fill by taking his career firmly into his own hands.

Emboldened by what he still considered to be the genius notion of a “Hound Dog”-howling Herod, and scarcely dismayed by his own lack of experience as either a songwriter or a playwright, O’Brien set to work writing his own rock ’n’ roll musical—one that would look not to the Bible for its inspiration, or to some idealized vision of the hippy underground; one that would not require nudity to attract attention, or some dubious message about the delights of drugs.

He was going to travel back to his own teenage years, to his own teenage fascinations, to the music that soundtracked his Antipodean adolescence; to the B-movies that had occupied his Taraunga dreams, and which still entertained him now, when they turned up on television.

He had no grandiose intentions. Rather, he wrote purely to kill time through the cold, dark winter of 1972–1973.

It was not a happy time for the British people. Inflation was soaring, and an ineffective government was flailing in its attempts to reign in the soaring costs. Prices were frozen and so was pay, precipitating a season of strikes and unrest.

Although wife Kimi had returned to the cast of Hair (as Chrissy, the role originally played by Sonja Kristina) following the birth of their son, the O’Brien family finances were frequently facing such dire straits that there was little to do beyond stay in and write.

The odd job did come along. Well, one job, when he was cast as a balding hippy in director Pete Walker’s new movie, The Four Dimensions of Greta. A thriller in which a German journalist journeys to London to try and locate his missing girlfriend, The Four Dimensions of Greta is best remembered today as the first-ever British movie to be shot with 3D sequences (usually those involving large-breasted blondes). But it’s classic Walker all the same, a follow-up of sorts to his earlier, magnificent (1970) Cool It Carol, and while one does not watch it for O’Brien’s part (which is tiny enough that it’s very easily missed), it’s an enthralling piece.

Shooting over, it was back to the typewriter, although O’Brien didn’t actually regard his project as writing. He was simply enjoying himself by killing time. He had a rough outline of how he saw the plot developing, had determined how the story would start and how it would end, so it was just a matter of filling in all the gaps in the middle.

Likewise, he had already written a handful of songs that he thought might find a place in the play, but he had no firm idea of where, or even if, they belonged.

It was a lot like doing a jigsaw puzzle, albeit with most of the picture box missing; and it was not until he started to show his work to various friends, sang them some of the songs, and let their advice and experience guide his own enthusiasm that O’Brien finally admitted even to himself that he’d actually written a stage show. Before that, it was still just a piece of fun.

One evening, another former Hair performer, Belinda Sinclair, and her boyfriend John Sinclair were visiting the O’Briens and watching just such a movie as had inspired their host’s imagination. Suddenly O’Brien picked up his acoustic guitar and started strumming and singing what would become “Science Fiction Double Feature,” while Belinda, John and Kimi threw their own suggestions and encouragement at him.

On another occasion, O’Brien mentioned that he was writing a rock musical to Jim Sharman, one of the few voices on the Jesus Christ Superstar team who actually approved of the Elvis Presley idea—although this time, it was a comment that Sharman probably greeted with a groan to begin with.

Everyone in theatre seemed to be writing rock musicals at that time, and most of them were religion themed. In fact, that was the first thing Sharman asked. “It’s not religious, is it?”

O’Brien shook his head. No, it definitely wasn’t religious.

Sharman breathed a sigh of relief and asked to hear more. And a notion, though none could have known it, was about to be born. Because there was so much more to come besides that song. So many other elements that would impinge upon O’Brien’s mind and seep into the concept’s consciousness.

The Gumshoe Was a Pussy Magnet

For the working title of his musical, O’Brien reflected back to an old episode of The Twilight Zone, the western-themed “Mr. Denton on Doomsday.” He called it They Came from Denton High.

Rocky, the germinating musical’s Frankensteinian hero, stepped out of the weight-lifting magazines that had long been among O’Brien’s favorite reading material; without ever indulging in the pastime himself, he ranked bodybuilding alongside rugby as his favorite sporting activity, at the same time as describing it, to journalist Phil South, as one of the “vulgar streaks” that shaped his outlook on life. Rock ’n’ roll, B-movies and weightlifting, vulgar streaks one and all.

The script came together, and again O’Brien looked abroad for inspiration. That glorious moment where Frank demands to know whether Janet has any tattoos, sprang from an incident backstage at Jesus Christ Superstar, when the troupe was visited by a group of young priests from St. Paul’s Cathedral.

In the midst of the ensuing polite, if slightly strained, meeting of minds, a voice was heard to rise above the hum of conversation, Paul Jabara asking one of the priests, “Tell me, do you have any tattoos?”

The priest stumbled his response, a negative, of course. At which point Jabara turned to one of the red-faced youngster’s colleagues, a higher rank of clergy, and sighed, “Oh well. How about you?”

The song “Superheroes,” with its unforgettably bleak reminder that “the beast is still feeding,” he later credited to an afternoon spent at the Saville Theatre in London, watching black-comedy genius Leonard Rossiter in the title role of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui in 1969.

And for the crucial scene in which the musical’s most conventional protagonists, Carol and Ricky (as Janet and Brad were originally named), first approach “the Frankenstein place,” O’Brien rekindled a scene from an old Carter Brown novel, The Lady Is Transparent.

Like O’Brien, Brown was born in England, but emigrated to Australia in 1948, shortly after getting married. There he settled into a phenomenal, and phenomenally productive, writing career; at one point, Brown was delivering to his publishers one novella and two full novels every month. By the time of his death in 1985, Brown had published no fewer than 322 novels, hard-bitten adventure yarns whose often lurid covers and evocative titles were themselves as much a part of the reading experience as the stories themselves.

Hardly surprisingly, given the schedule at which he worked, not all of his books were great, but when he was good he was spellbinding . . . and almost literally so when he delved into the occult. The Passionate Pagan; Blonde on a Broomstick; House of Sorcery; Walk Softly, Witch; The Coven; they may not be great literature, but several generations of readers awaited each new title with delirious impatience, and the young Richard O’Brien was one of them.

“They were paperback pulp fiction,” O’Brien explained in an interview for the Milton Keynes Theatre in England. “Reading matter—I won’t call them literature—. . . for under-educated adolescent males, a bit like the James Bond books. . . . The writing is just as puerile, but also just as enjoyable and very much targeted at men. The girls . . . are always slightly available and big breasted and all that stuff.”

Published in 1962, Brown’s The Lady Is Transparent is another in that redoubtable sequence of occult thrillers, a ghost-ridden locked-room mystery for police detective Al Wheeler; and what do we read as the cop first heads up to the scene of the crime, in the middle of a raging thunderstorm?

Another flash of lighting split the sky. it gave me a quick glimpse of the house maybe a hundred yards ahead—a solid mass, bone-white in the lightning, with a fantastic roof line that looked like it was all turrets and gables . . . .

Another convenient flash lit up the porch for long enough for me to see the huge bell hanging at one side of the massive front door and the rope that hung from it. I gave it a couple of sharp tugs and it rang like the knell of doom above the muttering chorus of thunder.

Seriously, the only things missing are the sign warning “Enter at your own risk” and a misshapen butler . . . named Joe Vitus in O’Brien’s original scheme, but swiftly rechristened Riff-Raff . . . to open the door, with the sinister greeting “you’re wet.”