7

Behind the Scenes—Casting the Crew

With the Royal Court staff firmly on his side, Jim Sharman set about recruiting the crew and cast that would bring The Rocky Horror Show to reality.

He had a three-month window in which to work: from mid-March, with The Unseen Hand on display, to mid-June, and the still-incomplete production’s scheduled debut.

It was a good thing that he enjoyed working under pressure, although it turned out that he already knew most of the people he’d be recruiting to his side.

Brian Thomson (Set Designer)

Having first met at Heavenburgers, on Sydney’s Oxford Street, in 1969, Sharman and Thomson had since become virtually inseparable, working together on a slew of productions through and beyond the next decade (see sidebar for details).

Since that time, and in and around his collaborations with Sharman, Thomson’s visionary designs have dignified stage productions around the world. He has worked for opera companies in both Australia and the UK (including Opera Australia, the English National Opera and the Welsh National Opera), while his movie credits include the Australian hits Starstruck (1982), Rebel (1985) and Ground Zero (1987). He was production designer for the closing ceremony of the Sydney Olympics in 2000, the 2003 Rugby World Cup and the 2006 Commonwealth Games.

His work on The Rocky Horror Show—both onstage and on-screen—meanwhile, is recreated almost every time a fresh rendition of the play is staged; while his contributions to the legend are not restricted to the visual. He also enjoyed a songwriting partnership with arranger Richard Hartley.

Richard Hartley (Musical Arranger)

Composer, arranger and keyboard player Hartley had already been employed as musical director on versions of The Threepenny Opera and Dionysus 73 when he met Richard O’Brien and Jim Sharman at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs, during preparations for The Unseen Hand; in fact, it was Jim Sharman who made the initial introduction to O’Brien, bringing the musician over to the playwright’s apartment one evening, to hear the songs that were destined for They Came from Denton High.

According to Sharman, Hartley, too, shivered with fear when he first heard what O’Brien was then engaged with creating. “Oh no, not another rock musical. . . .”

The quality of the songs, raw though it was, convinced him otherwise. Interviewed for the Milton Keynes Theater, Hartley explained, “He showed us the premise and we liked it . . . because it was a throwback to the movies of my formative years.” Not until they reached the rehearsal stage, however, would the songs truly come to life, “which is how things were done back then. Richard had the ideas and I just made them work, changed things, moved things around and made them work for the cast we had. Basically I just put in references to every rock ’n’ roll record I’d ever liked in there and there we had it. If you listen you can hear everything from Del Shannon and The Platters to the Rolling Stones and early Bowie.”

Unquestionably responsible for the sonic glue that bound what could otherwise have been a most disparate bunch of compositions, Hartley also played keyboards throughout the original stage production (and accompanying cast recording) and pieced together the band as well—guitarist Count Iain Blair, former Bonzo Dog Band bassist Dennis Cowan, drummer Martin Fitzgibbon and saxophonist Phil Kenzie, fresh from providing similar services to the London cast of Jack Good’s Catch My Soul.

Following The Rocky Horror Show, Hartley would continue to work with Sharman on a variety of productions, while also establishing himself as an in-demand composer for both theater and screen.

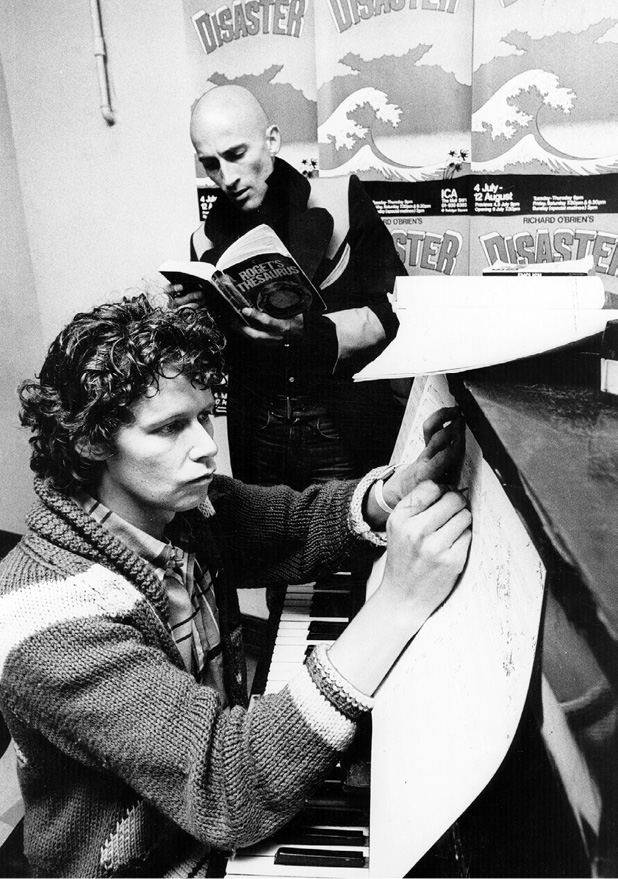

Among his celluloid triumphs can be numbered Aces High (1976), The Lady Vanishes (1979), Bad Timing (1980), Alice in Wonderland (1999) and many more. He has continued to work with Richard O’Brien on occasion, scoring the post-Rocky musicals T. Zee (1976), Disaster (1978) and The Stripper (1982), the Shock Treatment movie (1981), the unfinished Revenge of the Old Queen, and, announced in 2015, Alive on Arrival, described by O’Brien in a BBC interview as “a little musical . . . about a girl that goes to the land of the dead and she’s still alive. No idea whether it’s got any legs on it, but I’m enjoying fiddling around with some words.”

The Richards Hartley and O’Brien at work composing in the late 1970s. Posters behind O’Brien celebrate his latest creation, 1978’s Disaster.

© Evening Standard/Getty Images

Sue Blane (Costume Designer)

A student in Costume Design College of Art in her hometown Wolverhampton, Sue Blane relocated to London to complete her studies at the Central School of Art and Design. She graduated in 1971 and was already a burgeoning presence in the world of theater when she was first offered a role in The Rocky Horror Show.

Considering just how integral her work would become to the final production, and its manifold incarnations since then, Blane was not, to begin with, at all convinced that it was the right job for her. Harriet Cruickshank, the Theatre Upstairs’s manager, made the introduction, but Blane was unimpressed.

The story, she thought, sounded awful, and the proffered rate of pay was minuscule—certainly when compared to the amount of work that it would require. She saw little reward in breaking her back for what was surely destined to prove a short-lived fringe production.

A meeting with Sharman at a pub close to the Royal Court Theatre changed her mind, and the casting of several of her friends, including Tim Curry and Rayner Bourton, was the icing on the cake. By three o’clock that morning, with both Blane and Sharman beginning to feel the first effects of what was destined to become a monstrous hangover, she had agreed to do it.

Armed with a meager $400 budget, Blane set about touring London’s thrift stores and flea markets, collecting the props that she knew would be invaluable.

In an age before eBay and the Internet conspired to convince every junk store owner that their entire stock is worth a fortune, London was littered with tiny, out-of-the-way stores that overflowed with the detritus of the city’s past—discarded furniture that no self-respecting shopkeeper would have even dared to label “antique”; out-of-date clothing that had yet to acquire the cachet of “vintage”; broken-down ornaments that would never have been termed “collectible.” It was just junk, and Blane was the magpie who sorted through the heaps, seeking the pieces she required.

And then she worked her magic.

The Rocky Horror Show remains the production for which Blane is best known; it was, however, just one early stage in a career that has confirmed her among her profession’s most renowned artists.

She has worked with Jonathan Miller, Roman Polanski (the 1997 musical based around his then thirty-year-old movie The Fearless Vampire Killers), David McVicar and Disney.

Her designs have graced the stages of the English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Scala, and the Bayreuth Festival; and the costumes she conceived for the English National Ballet’s production of Alice in Wonderland saw her nominated for the 1997 Laurence Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance. In 2003, she received an MBE (Members of the Order of the British Empire).

Andrew O’Bonzo (Music Publisher)

Throughout their time with Hair, Richard and his soon-to-be-wife Kimi became close friends with several of their fellow crew members, among them John Sinclair (at one point, Belinda Sinclair’s boyfriend) and his (non-acting) friend Andy Leighton.

The two were planning to start their own recording studio at the time—later to emerge as SARM in Whitechapel, with its earliest clients including the original London cast recording of The Rocky Horror Show. The pair were also in the process of launching a music publishing company, Druidcrest Music. O’Brien became the company’s first signing once it was up and running, and soon became an equal partner in the company as well.

Later, the three would launch their own production company, Rich Teaboy Productions, releasing a string of Rocky Horror–related singles by both cast members and their friends (see Appendix Two—Discography). They also adopted a pseudonym to front their shared activities. Andrew O’Bonzo—a titular tribute to the trio’s shared passion for the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band of late sixties comedic and music fame—was born.

Michael White (Producer)

Born in Glasgow, educated at the Sorbonne, and a Wall Street runner in the New York of the 1950s, Michael White entered the world of theater following his return to the UK in the late 1950s. Pursuing a long-held interest in theater, he became assistant to Sir Peter Lauderdale Daubeny, as he launched the renowned World Theatre Season at the Aldwych Theatre in London (home to the Royal Shakespeare Company), with the cosmopolitan goal of introducing British audiences to new plays from around the world.

In 1962, White made his own debut as a West End producer, overseeing Jack Gelber’s The Connection; since that time, he had handled works as disparate as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1966); the long-running Sleuth (1969); and, most notoriously, Hair, Oh! Calcutta! and The Dirtiest Show in Town.

He was instrumental, in 1967, in plans to bring Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground to London, for a weeklong engagement at the Chalk Farm Roundhouse, beginning May 21, 1967—a significant venture in that it would have marked the first and only time the original incarnation of that so-legendary band, featuring Lou Reed, John Cale and Nico, made it to European shores. Sadly, events conspired to stymie the shows, among them White’s own schedule calling him to New York, at precisely the time Warhol would be in London, to oversee the launch of his production of Joe Orton’s Loot.

White was introduced to The Rocky Horror Show by Nicholas Wright. He detailed that phone call in the booklet accompanying the show’s fifteenth-anniversary CD box set.

“I received a phone call from [Wright], who said they were doing a new musical in the Theatre Upstairs and were looking for a producer to put up £3,000 towards the cost of production, in return for the West End rights.” And later, in his autobiography, he described it as a career high point he never tired of.

“Many of my productions I have admired objectively, abstractly. I loved every minute of Rocky Horror . . . it is the only show I have ever done that I can watch time and time again—I must have seen it a hundred times. It is snappy; only an hour and twenty minutes; non-stop, no interval. Every three minutes you are being socked with another song or event. Everything about it works. The Rocky Horror Show is critic proof.”

In later years, White would work with some of the greatest comics of the British 1970s and 1980s, both as producer of the movie Monty Python and the Holy Grail and then as co-creator of The Comic Strip Presents, an early 1980s TV series starring (among others) Dawn French, Jennifer Saunders, Ade Edmondson and Nigel Planer.

White published his autobiography, Empty Seats, in 1985, and was the subject, in 2013, of Gracie Otto’s documentary The Last Impresario. It was a fine portrait of, and a fitting tribute to, a man who had seemingly dedicated his career to confronting the British theatergoing public with the unusual, the risqué and the controversial.

Jonathan King (the Record Company Man)

The sheer quality of the music composed and performed throughout The Rocky Horror Show was evident from the outset. Indeed, the play had been onstage for exactly two nights when English record producer and habitual hit maker Jonathan King, lured into the theater by a rave review in that morning’s Daily Mail newspaper, arrived backstage; introduced himself to the theater’s manager, Harriet Cruikshank; and asked if he could release a cast album on his own UK Records.

A deal was agreed more or less on the spot, and by early August, the LP was in the can, recorded during one manic twenty-four hour session at John Sinclair’s SARM East Studios in London.

Having made that initial stake, King would become heavily involved in The Rocky Horror Show’s early promotion, while also throwing his financial weight behind the show by joining Michael White as a backer. UK Records, meanwhile, was still a comparative fledgling at the time, just a handful of singles and albums old. Alongside the maiden LP by the rock band 10cc, The Rocky Horror Show Original London Cast album, only its sixth full-length release, would place the label firmly on the British musical map.

Integral though he was to the ongoing success of The Rocky Horror Show, Jonathan King has nevertheless suffered the same fate as those other early participants who either dropped out or faded away prior to the movie, and been largely forgotten by history. In fact, anybody present that night when he burst backstage to introduce himself can probably still recall the sheer enthusiasm and excitement on his oddly owlish face, even as they perhaps cringed a little at the prospect of becoming involved with him.

For Jonathan King’s name has seldom been associated with what we might call “great music.” And that is just how he prefers it.

Age seventeen, and fresh out of public school, King first reached the British Top 5 with his debut single, “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon,” in 1965. And in the years since then, he had become one of Britain’s most prolific hit makers, because he was, quite simply, a musical genius. Unfortunately for his critics, his genius lay in determining the lowest possible common denominators in the realms of public taste and then force-feeding them to everyone else.

Upon leaving Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1966, King landed his own television show, Good Evening. It ran for six months, giving King ample opportunity to work on the image that remains with him even today, that of a spineless cynic whose respect for the record-buying populace went down another couple of notches every time they bought one of his own records.

Yet he was also responsible for some remarkable feats of prescience.

It was King who first spotted, and signed, a band formed among the pupils of his own alma mater, Charterhouse School, and christened them Genesis. It was King who first recorded the Bay City Rollers; it was King who took a chance on four session musicians laboring away in their own tiny studio in northern England and suggested they call themselves 10cc. And it was King who realized what a monster The Rocky Horror Show was set to become, before any other industry figurehead had even heard of it.

And yet . . . .

And yet, he was also responsible for some of the most misshapen ear worms ever to gnaw the brains of the record-buying public. Under a bewildering variety of pseudonyms and disguises (and wigs), King was to spend the seventies, and most of the eighties too, first spotting and then exploiting every crack in Great Britain’s musical armor. And the crasser it was, the better.

His version of the Archies’ hapless bubblegum hit “Sugar Sugar,” recorded under the name Sakharin in 1971, mercilessly employed every trick in the heavy metal song book, right down to the sub-Hendrix guitar that warbled the hookline.

“Johnny Reggae,” ostensibly by the all-girl Piglets, was a fearless updating of fifties teen romance, seen through the eye of a young lady who was dating a skinhead. And a violent cover of B. J. Thomas’s sappy American hit “Hooked on a Feeling” rode a repeated refrain of “Oogachucka, ooga-ooga-ooga chucka . . .” for no better reason than the fact that the original didn’t.

St. Cecilia’s “Leap Up and Down, Wave Your Knickers in the Air” was banned for reasons that one probably doesn’t need to expand upon; and when he launched UK, he did so with a positively disreputable-sounding revamp of the oldie “Loop Di Love,” recorded under the name of Shag. An English slang term for sexual intercourse, of course.

Hit followed hit followed hit. At one point UK was operating on a hit ratio of one in ten, at a time when most record companies considered themselves to be doing extraordinarily well if they managed half of that.

When Dutch singing group Pussycat had a hit with “Mississippi,” King was out there counseling the British people to be patriotic and buy his version instead. When the George Baker Selection threatened to have a hit with “Una Paloma Blanca,” King preempted it with a rendering even weedier than the original. A tentative Glenn Miller revival, spearheaded by “Moonlight Serenade” returning to the British chart, was celebrated by King’s “In the Mood”; and the American success of Tavares’s “It Only Takes a Minute” was echoed in Britain when UK rush-released 100 Ton and a Feather’s infinitely preferable cover version.

When the Sex Pistols released “God Save the Queen” in June 1977, King retaliated with “God Save the Sex Pistols,” by “Elizabeth R,” and doing the Pistols’ cause irreparable damage with the line, “Anarchist, anarchist, anarchist the girl next door.”

And finally, when Britain was suddenly smitten by hideous blue elf-like creatures named Smurfs, models of which were given away free by a leading chain of gas stations, King struck a blow for ecologists everywhere by unleashing Father Abraphart & the Smurps’ condemnation of leaded fuel—”Lick a Smurp for Christmas (All Fall Down).”

In 1997, he was awarded the British Phonographic Industry’s Man of the Year Award, with no less a judge of character than then-prime minister Tony Blair offering up a message of congratulations. But subsequent years have been less kind to both King and to his reputation. In 2000, he came under investigation in relation to allegations of historical sexual offenses committed against underage boys. He was ultimately sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment.

He was paroled in 2005 and has continued to protest his innocence, while also establishing himself among the country’s leading prison reformers. Whatever he may or may not have done, however, it does not alter one essential fact.

An evening spent with Jonathan King’s greatest hits is not one that you will forget in a hurry.

Oogachucka.