8

In the Spotlight—Crewing the Cast

Nobody who auditioned for The Rocky Horror Show in the weeks and months before it made its debut ever believed it would become as huge as it did.

Most couldn’t believe it was even going to open.

Rayner Bourton, the actor who portrayed Rocky in the first London run, even confessed that he thought it was “tacky,” when he initially read through the script, and simply “couldn’t believe” that it was being staged by the Royal Court, “a very prestigious theatre company, dedicated to new work.”

More surprises followed, for Bourton and the rest. Among the demands that Jim Sharman made on them was a solid grounding in the art of camp—as when he organized that outing to the movies to watch Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

Barry Bostwick, who played the part of Brad in the subsequent Rocky Horror movie, later explained to Scott Miller, author of the book Inside Rocky Horror, “There was a slight over-the-top acting that was required [by Rocky Horror], yet it had to be grounded in reality and very real. Sort of fifteen percent hyper-ness that had to be added on top of every character’s reality.”

Unless, of course, you were discussing Tim Curry. For him, that fifteen percent came naturally.

“When Richard O’Brien conceived Frank,” Jim Sharman wrote in his memoir, “I’m sure he had in mind a lovely dress, an elegant staircase and probably himself. It didn’t quite turn out that way.”

Part of the blame was O’Brien’s own; by the time The Rocky Horror Show came to fruition, he had abandoned any earlier notion he might have had of taking the play’s lead role, and set his heart on playing Eddie.

Part of the blame was Sharman’s, who could not even look at O’Brien’s “wiry” frame without immediately flashing on F. W. Murnau’s classic vampire flick Nosferatu, and casting him instead as Riff-Raff.

Meaning, the part of Doctor Frank-N-Furter was still up for grabs.

And part of the blame was Tim Curry’s, because he was the one who grabbed it. Yes, other people could dream of being Frank, and others still could play him. As indeed they have done for the past forty years.

But for anybody who witnessed The Rocky Horror Show in its earliest prime, no matter how many subsequent productions they’ve seen since then, only one person actually is the demon doctor, and that person was born on April 19, 1946, in the unprepossessing village of Grappenhall, near the northern English town of Warrington.

Tim Curry

Timothy James Curry was the son of a Royal Navy Methodist chaplain, James, and a school secretary, Patricia. It was a musical family; Curry’s sister Judy was an aspiring concert pianist, and little Tim was likewise always drawn to performance. He was a soprano in his local church at age six and, thanks to the annual school play, a Shakespearean actor at ten.

His father passed away when the boy was twelve, and the family moved to London. But Curry himself was sent away to boarding school, Kingswood School in the western city of Bath. He then moved to Birmingham University to study drama and English.

He graduated in 1968 with a combined degree, a BA in drama and theatre studies, and it was that same year that he firmly envisioned his future—not as an actor, not as a singer, but as a single, singular star. In fact, he could even pinpoint the moment when he reached that conclusion, the night that he and his college roommate, fellow drama student Patrick Barlow, attended a performance of Cabaret at London’s Palace Theatre.

Before Liza Minnelli made the role of Cabaret’s female lead her own, courtesy of its 1972 movie adaptation; and ahead, too, of Judy Haworth who played the part on Broadway, there really was just one Sally Bowles.

Actress Judi Dench is best regarded now as one of the so-called national treasures of the British movie hierarchy; the Queen in Mrs. Brown; “M” in noughties James Bond; Dame Sybil Thorndike in My Week with Marilyn [Monroe]; and so forth. Back then, however, she was still a relative unknown, personifying a part that—if you had only read the original books (Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Trilogy)—might well have seemed impossible to capture.

She captured it.

Tiny, vulnerable, beautiful, frail, Dench dominated the stage, and when she stepped into the spotlight alone, the entire audience held spellbound in her palm, the watching Curry whispered to Barlow, “That’s what I want to be.” Twenty-four hours, he and Barlow auditioned for a street theater troupe in Chalk Farm. Scarcely any time later, Curry landed his first major role, in Hair.

He was not a complete novice. At college, he played with both the drama department and a local theater, while his student group were twice winners of the Grand Prix at the World Festival of Student Drama in Nancy, France. Hair, however, was more than a single step up the ladder—in the character of Woof, he was prominent in three songs, “Don’t Put It Down,” “Electric Blues” and “Eyes Look Your Last.”

Elsewhere, too, it was hard to miss him. Interviewed by the Guardian newspaper in 2006, Patrick Barlow enthused, “[Curry’s singing voice] was just completely perfect, just something he was born with—it came ready-made. We would go to university parties and end up having a drink and whatever and he would break out into song, this marvelous bluesy voice.”

Curry remained with Hair until early 1970, following it up with further studies and acting engagements as far apart (in geographical terms) as the Royal Court in London and from there, the Citizen’s Theatre in Glasgow, at a time when that particular institution was taking its own especial advantage of the end of censorship.

Practically dead on its feet when the Lord Chamberlain finally rolled over, the Citizen’s was reborn the following year, with the arrival of a new artistic team, Giles Havergal and Philip Prowse, and a whole new attitude toward stagecraft—a season filled with the most populist plays they could conceive of, performed like they had never been before.

The season began with an all-male Hamlet that opened with a barely sheeted sex scene, dressed its gravediggers in loin cloths and the rest of the cast in black. The familiar text was sliced and diced, the cast instructed to behave as though they were approaching mental meltdown, and the cream of Scotland’s theatrical media was invited to witness the ensuing cataclysm.

Hamlet was hammered, but not only for its perceived ineptitude. There was a sexual edge to the production that was darker and more dangerous than anything the city—nay, the country—had seen before, a whiff of corruption and immorality so strong that it practically warped minds before the curtains even raised. Or at least, that was how the media portrayed it. And, of course, the public just had to find out for itself.

The Citizen’s Theatre was reborn, and it was there, in the heart of the city’s once notorious Gorbals district, behind the crumbling facade of battered Corinthian columns, within that cozy womb of red and gold, green and black, with the stage supervised by gold, plaster-cast goddesses, that Curry first encountered one of the women whose vision would be responsible for maintaining that rebirth, costume designer Sue Blane.

He was not the only name in contention for the role of Doctor Frank-N-Furter. Several others had already been bookmarked as distinct possibilities, including American Jonathan Kramer, fresh from Warhol’s Women in Revolt. But the moment Curry walked through into the audition at the Irish Club on Sloane Street, to perform Little Richard’s “Rip It Up” for the astonished watchers, he more or less got the job on the spot.

Curry recalled his audition in a syndicated interview with journalist Frank Lovece in 1992. Of course, he already knew Richard O’Brien from their shared experiences in Hair, and he was aware, too, that the out-of-work actor was now doubling as an out-of-work playwright.

“I’d heard about the play because I lived on Paddington Street, off Baker Street [above the Speed Queen laundromat] and there was an old gym a few doors away. I saw Richard O’Brien in the street, and he said he’d just been to the gym to see if he could find a muscleman who could sing. I said, ‘Why do you need him to sing?’ And he told me that his musical was going to be done, and I should talk to Jim Sharman. He gave me the script, and I thought, ‘Boy, if this works, it’s going to be a smash.’”

“The casting of Frank-N-Furter [was] crucial,” O’Brien told The Scotsman newspaper. “Wit and intelligence is what you need. And that sense of danger, that he might climb over the footlights and roger the wife—and he may well roger the husband as well. It’s that kind of ambivalence that makes him dangerous and appealing, cheeky and charming, charismatic and selfish and all the things that he is.”

Interviewed by Film Talk in 1975, Curry continued, “When I read it, I just thought it was very, very funny, and the most kind of economical script that I’d read for a very long time.” He admitted, with stunning prescience, “I was hesitant in that if it worked, it might be a very difficult image to shake off. But really, I have always thought that [acting] isn’t worth doing unless you took a risk. . . . So I took a risk.” According to Rayner Bourton, Curry actually passed up two television offers in order to play Frank.

The team’s vision of Doctor Frank-N-Furter, however, was still far from the finished item. In O’Brien’s original script, he is the archetypal Mad Scientist, clad in a white coat and fiendishly devoted to science without any care, or even awareness, of its effect on his fellow human beings.

With this glorious archetype in mind, Curry was understandably considering adopting a German accent for the role. This then became a more traditionally Transylvanian tone, which gave way in turn to an American twang. But then he remembered the evening spent riding the Number 19 bus, when he overheard two very aristocratic-sounding English women discussing their respective living arrangements.

“There is a particular kind of social group, sort of Knightsbridge, who wear headscarves knotted under the chin [and] Louis Jourdan shoes,” he explained to Interview magazine in 1976, and this pair were fine examples of that.

“Do you have a house in town, or a house in the country?” one inquired of the other, each word positively glittering with cut-diamond finesse. And before the words were out of her mouth, Curry had his Frank ’n’ accent, a tone that he described as a combination of Her Majesty the Queen and his own mother’s telephone voice.

But the voice was one thing, and the personality was quite another. “I didn’t actually base the character on anybody, really,” Curry continued when he spoke with Interview. “The Americans have thought Bette Davis much more than the English, because it’s partly, I think, using a very cold English accent which makes people think Bette Davis. I didn’t actually base it on Joan Crawford or Bette Davis, but I do like them very much, of course.”

Another tentative influence might well have been David Hayman, one of Curry’s contemporaries at the Citizen’s, and Hamlet himself in the 1970 play.

“I loved getting up people’s noses,” Hayman told Michael Coveney, author of the theater’s 1990 history The Citz. “Brecht said that theatre should create moral scandal and [Havergal and Prowse] understood that very well. It was a heady time and the life-style we were involved in was almost as exciting as the work itself. We were playing with our sexuality onstage and off. I was wearing eye make-up, an ear-ring, a woman’s fur coat, a great sombrero hat and my hair down to my shoulders. I remember [my] aunts and uncles . . . running from me in the street as this vision bore down on them.”

Remind you of anyone?

The German accent was not gone forever. Patricia Quinn promptly seized it for Magenta, and by the time of the previews, it had devolved, too, to Doctor Scott . . . or Doctor Von Scott, as Frank cattily informs his guests. Hitherto, the old scientist had also been an unabashed American, and maybe one scientist was enough. For around the same time as Curry decided on an accent, Jim Sharman threw away his old white coat and handed him a black corset and fishnet tights instead.

As it transpired, Curry was no stranger to this particular costume. Two years earlier, at the Close Theatre Club adjunct of the Citizen’s Theatre in Glasgow, Curry appeared as the sadomasochistic housemaid Solange in the flamboyantly outrageous Lindsay Kemp’s production of Jean Genet’s The Maids.

He was clad, every night, in a tight black corset that Sue Blane picked up for pennies at Paddy’s Market in Glasgow, and when Blane herself was recruited to The Rocky Horror Show, one of the first calls she made was to Kemp, to ask if she could have that same corset back.

Kemp agreed, but still he was shocked by the use to which it was to be put. Interviewed for actor (and future Doctor Frank-N-Furter) Daniel Abineri’s Walk on the Wild Side documentary, Kemp recalled being “mortified when the curtain went up and there was the bloody costume. Mortified!”

Neither, as it turned out, was Richard O’Brien strictly unaware of the implications of this sudden bout of gender bending. It would be some forty years before the writer commented openly on the subject, but in 2013 he spoke of having undergone estrogen therapy for the past ten years.

He now considered himself to be 30 percent female, while also explaining, in a 2006 interview with Cate Mackenzie, that “being transgender is a card you’re dealt, and you don’t know how to deal with it because society doesn’t allow it.” The reassigning of Frank’s sexuality, no matter how random it seems on paper, clearly addressed other themes within O’Brien’s life as well.

With the corset cemented into the wardrobe, further elements fell into place. Blane’s original vision of topping her creation with a platinum blonde wig was supplanted by wild, dark, feminine curls, while Doctor Frank-N-Furter’s choice of footwear would also become a defining accouterment—namely, the largest available ladies shoes into which Curry was able to squeeze his size eights. Curry later admitted that only once he had established the Doctor’s choice of footwear could he begin building the rest of the character.

Still it was a demanding role, and that was where Jim Sharman’s influence and experience came into play.

As a child, the director had been in the audience when Bobby Le Brun, a famous Australian pantomime dame (who actually looked like “a stevedore in drag”), leered out at the audience and threw chocolate-covered caramel candies, Fantales, into the crowd.

Three were hurled in Sharman’s direction before he finally caught one, but that, he reflected later, was the moment when the showbiz bug bit him. So when Tim Curry, still finding his way into the role, asked “How far should I go?”, Sharman had no hesitation in replying, “Just stop before you throw Fantales to the kiddies.” Like he said during that 1995 lecture at the Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney, “the audience thought they were seeing a hip, streetwise character in a rock ’n’ roll show; we knew it was a panto dame in mufti.”

Doctor Frank-N-Furter was unquestionably destined to become the pivotal role in Curry’s entire career, effectively informing every successful part he has played since then—a roll call that ranges from greasy rock star to über-camp devil.

The actor himself, however, has frequently shrugged off the suggestion that it is also his most self-defining part. Indeed, by 1979—just four years after the release of The Rocky Horror Picture Show movie—Curry was actively denying the role had any significance whatsoever.

It was, he said in one particularly ill-tempered interview, nothing more than a single piece of work he did five years earlier. The fact that the critics still drew (and continue to draw, all these years later) upon that role as the ideal for all that Curry went on to achieve in its aftermath, he continued, said more about their preconceptions than it did his abilities.

Indeed, how bored would we have been, and how boring would it be for Curry, if every part he’d played since then had reprised Doctor Frank-N-Furter one more time, until even the most dramatic performance could not be considered accomplished until he’d ridden an elevator in cape and platform boots, made his leading lady squirm with some beautifully phrased non sequitur, and then eaten Meat Loaf for supper.

Every actor dreams of producing a performance that will ascend into Hollywood legend; every one hopes to create a personification that will become a benchmark for every future role player. But, with the possible exception of David Bowie (who has effectively played the precise same character in every movie he has ever made), none would then want to reprise it again and again and again. And neither would the critics permit them to.

Those same critics, as Curry pointed out, who simultaneously complained that he didn’t do that.

“Journalists come to my show with preconceived notions of who I am,” he told JAM magazine in 1979. “They know they can get column space in their papers because of . . . Rocky Horror. . . . They can always say, ‘Well, he wasn’t as good as the movie.’ They can write six inches of copy alongside [a picture] of a guy wearing a corset and stockings, then get into a heavy metaphysical speculation about the image. I never gave a shit about my image. “

Neither was he simply being contrary for the sake of it. Richard O’Brien, too, has acknowledged that Doctor Frank-N-Furter’s transvestism was never regarded among the play’s key elements. It was selected not for what he perceived, in 1972–73, would be its shock value, but because the theme of drag itself was enjoying such theatrical currency in the world of glam rock.

David Bowie spoke of wearing men’s dresses and had a portfolio of photographs to prove his sincerity. Andy Warhol’s caravan of “superstars” was largely staffed by men who made fabulous women; and Lou Reed’s Transformer album went Top 20 with a photo of a dragged-up male (Ernie Thormahlen) on the cover.

The Kinks’ “Lola,” in which the innocent protagonist knows that he’s a man and quickly discovers that his new lady friend is as well, was less than three years old; and a new band rising on the London club circuit did not call itself Queen out of admiration for royalty.

That was the atmosphere that spawned Doctor Frank-N-Furter, and the fact that his image came to define both the show and its star was, in so many ways, absolutely accidental. All O’Brien had hoped to fashion was a creature who bridged the void that stretches between Ivan the Terrible and Cruella de Vil.

Having created his Frankenstein, however, O’Brien readily absorbed both the credit and the blame for its afterlife. In 2010, interviewed by the Cocklenuggets blog, he recalled the sight that met his eyes on the first night of The Rocky Horror Show’s thirtieth-anniversary bash at the Queens Theatre in London.

There was a man climbing up the stairs . . . on his hands and knees because the heels of his shoes were far too high to walk on . . . .

He was climbing and his arms were splayed and his knees were ambling up and his arse was in the air and he has a leather thong on and a hairy arse and I remember thinking “oh that is so disgusting, that is dreadful.” And then I thought, “oh dear God, Oh God, I’m partially responsible for this. I’ve given this person the opportunity to do this.”

It was for that reason (and many more, of course) that, of all the roles in The Rocky Horror Show, the one that few folk believed could be duplicated was Doctor Frank-N-Furter. It is one of the triumphs of theater history that so many people have since stepped into those shoes.

Paddy O’Hagan

With Tim Curry ensconced as the magisterial star of the upcoming show, O’Brien was persuaded by Sharman to star as the antiheroic Riff-Raff—hitherto, he had set his heart on playing the rocker Eddie, a role that now went to Paddy O’Hagan, a founding member of the experimental Pip Simmons Theatre Group, veterans of several past Royal Court Upstairs productions.

He was also a star of the spin-off The Pipkins, an early 1970s children’s TV series intended to rival the imported American Sesame Street, and featuring such characters as Hartley Hare, the Bag Lady, Sophie the Cat and O’Hagan’s character, Peter Potter.

Rayner Bourton

Among the other names put forward for the role of Frank, before Curry made it his own, the Theatre Upstairs’s manager Harriet Cruickshank had been championing one Rayner Bourton, a young blonde Adonis who had so impressed her as a daringly camp Patroclus in a Glasgow Citizen’s Theatre production of Troilus and Cressida, earlier in the year.

In any event, the resident casting director, Gillian Diamond, was less convinced. But she had another suggestion. What of the creature? The man-made Rocky whose horror not only was to form the backbone of the show, but would also title it too?

Birmingham-born Bourton had performed with the Glasgow Citizen’s Theatre, the New Birmingham Rep and the Chichester Festival Theatre before debuting his glorious vision of Doctor Frank-N-Furter’s Frankensteinian creation, and effectively blueprinting every subsequent performance of the role.

Indeed, so effectively did he do so that, almost alone of the original cast, Bourton did not ascend to immediate (or even gradual) stardom in the wake of his Rocky Horror years, a fate made more ironic by his confession, in an interview with the Birmingham Post newspaper in 2009, that he was not initially certain whether he even wanted the part.

“I can still remember how I felt when I got the script. The first thing you do as an actor—anyone who tells you they don’t is lying—is scan the pages and see how many lines you’ve got. I only had twelve.” But he hadn’t, he said, spent much time in London, and he was ultimately happy just to find work. “At the time, I didn’t think it would kill my career. But I did think ‘Am I going to get arrested?’”

Successful from the outset, Bourton was offered a long-term contract in the play, but turned it down, admitting today that he was far too intent on becoming a serious classical actor to sign away his time for a piece of tacky fluff—feelings and possibly regrets that he expands upon in his 2005 autobiography, The Rocky Horror Show: As I Remember It.

“I could have stayed a year as Rocky, which would have been very good for my career. Because, although we were big-time in London, not long after I left, the show exploded worldwide.”

At the same time, however, one cannot fault his original thinking. He had already proven himself adept at the kind of roles he now intended pursuing. Indeed, his acting career was effectively launched at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, and a role (a small one, admittedly, but everyone starts somewhere) in Richard Chamberlain’s acclaimed version of Hamlet.

That was in 1969, and he had continued working regularly since then, a classical actor who was nevertheless not averse to the occasional bit of fun. Indeed, Bourton opened 1973 by appearing in a pantomime version of Jack and the Beanstalk in Chesterfield.

While he was there, however, he tried out for the Glasgow Citizen’s Theatre, “to my mind the best theatre company in the world,” he wrote in his autobiography; and, unbeknownst to him, a training ground for both Tim Curry and Patricia Quinn.

According to his autobiography, he was promptly catapulted into the company’s productions of Tamburlaine, The Government Inspector, Troilus and Cressida and Happy End, a Kurt Weill production in which he was expected to transform from a twenty-three-year-old, six-foot blond Englishman into a sixty-year-old, five-foot-six Japanese tap dancer.

Neither of them would have realized the significance at the time, but he was aided in his quest by a costumier named Sue Blane.

The season closed in mid-April, and Bourton returned to London, with an invitation to rejoin the company in September. Immediately a new opportunity arose, a fringe theater production of Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal, directed by his old company manager from Birmingham, Tony Craven. Before work could begin there, however, Bourton received that call from Harriet Cruickshank—who, prior to joining the Royal Court, had herself been the general manager at the Citizen’s Theatre.

Auditioning at the Irish Club, Bourton performed a recent UK chart topper as evidence that he could sing—Little Jimmy Osmond’s ingratiatingly grating “Long Haired Lover from Liverpool,” which he had previously incorporated into his performance during Jack and the Beanstalk.

He made it through one verse before he heard Jim Sharman murmur wearily, “Okay, that’s enough of that”; pause long enough for Bourton to begin the long walk toward the exit and then hand him a piece of paper with another lyric entirely on it. “We’d like you to have a go at this.”

It was “Sword of Damocles,” signature song not of the fiendish Doctor Frank-N-Furter, but of the creature he had created for whatever foul ends he envisaged, Rocky Horror himself.

Bourton did not initially hear back from the Royal Court and assumed he had not won the part. He was not overly concerned—rehearsals for The Thief’s Journal, now retitled Beggar My Neighbour, were set to begin soon. Then the call came, not confirming the role was his, but at least explaining the delay. Sharman wanted him for the part, but O’Brien was still visiting the gyms, holding out hope that a genuine musically inclined muscleman would make himself known.

None would. Rehearsals would begin in two weeks’ time.

Patricia Quinn

There were hopes that Marianne Faithfull might be tempted to take up the role of Magenta, Doctor Frank-N-Furter’s sex-on-wheels maid and Riff-Raff’s beautiful sister.

It was not an idle wish. Already a screen favorite thanks to roles in French TV’s Anna (1967) and alongside Alain Delon in The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), Faithfull had confirmed herself as an equally accomplished stage actress with her role in Edward Bond’s controversial production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters at the Royal Court in 1969.

Sharman had even come close to working with her back in Australia; Faithfull was scheduled to costar with her then-boyfriend Mick Jagger in director Tony Richardson’s movie of Ned Kelly, while Sharman had just been recruited as assistant director. The position would not, in the end, work out, but still Sharman witnessed a moment of very high drama, arriving at the hotel where the cast and crew was staying, in time to witness Faithfull being wheeled out on a stretcher, after suffering a drug overdose.

She would not appear in the movie.

Three years later, Faithful remained a scion of scurrilous tabloid notoriety, the fallen angel of British pop struggling to rebuild a career that had been ravaged by tragedy, drugs and heartbreak. Unquestionably she would have been an inspired, and perhaps even inspiring, addition to the cast of The Rocky Horror Show.

Ultimately, it was not to be. Her “replacement,” however, was a masterstroke.

The daughter of a Belfast, Northern Ireland, bookmaker, Patricia Quinn was a champion gymnast at school and launched her acting career as a member of the British Drama League in Belfast.

Moving to London, she had already played a small part in the British TV serial Z Cars (where she met her first husband, producer Don Hawkins, in 1963) before she even started at drama school, while her burgeoning acting career was supplemented with a variety of other occupations—including being one of the original bunnies at the city’s first Playboy Club, after it opened on July 1, 1966.

She was there for only three months, but decades later, she told HollywoodChicago.com, “I did a documentary about [the club], and it was like a school reunion. We all ended up at a pub on the Thames owned by Barbara Bunny, and we became rather a raucous lot. It was brilliant, I loved being a Bunny.”

From London, in late 1969, Quinn moved into repertory in Glasgow, attending the same Citizen’s Theatre that would introduce so many other names to the Rocky Horror cast. There, director Philip Prowse described her as the most brilliant actress ever to pass through the theatre’s doors, a point that she reinforced with her performance, the following May, in the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs’s production of Heathcote Williams’s first-ever play, AC/DC.

It is a difficult play, a radical assault on what might (cynically but nevertheless accurately) be described as the mental health industry—or at least the dawning realization that psychiatric treatment no longer needed to be confined merely to the patients who actually needed it. It could be doled out to those who’d been convinced they needed it, as well. Alongside Kenneth Loach’s near-contemporaneous movie Family Life, with its own brutal portrayal of the psychiatric field’s potential for excess and abuse, it was a vicious vision of a free-for-all future that readily established Williams among the vanguard of new British playwrights and earned the London Evening Standard’s award for “Most Promising New Play.”

By the time The Rocky Horror Show came around, Quinn was beginning to find her way into television too, with appearances in such fondly recalled British series as the comedy The Fenn Street Gang, the crime drama Van der Valk and Saturday Night Theatre. She was also inching into the British movie world, with small parts in period comedies Up the Chastity Belt, Up the Front (in which she played a maid named Magda), Rentadick, The Alf Garnett Saga and Spike Milligan’s Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall.

Quinn recalled her introduction to the world of Rocky Horror.

It was Richard Hartley who placed her into contention, after he caught her playing Sarah Bernhardt in a recent production of Sarah B. Divine! at the Cochrane Theatre in Holborn.

She arrived at the Irish Club audition knowing only that she would be required to sing, and that her inquisitors would prefer to hear a rock ’n’ roll song. She selected Jesse Matthews’s “Over My Shoulder,” an up-tempo 1930s number, and she dressed the part, as well.

Her husband, Don Hawkins, was in Australia at the time, directing a touring version of the Who’s Tommy. Just days before the audition, Quinn received a package from him—a jacket with leopard-skin sleeves and a picture of the Taj Mahal on the back. She wore that to the audition, and, she told Gay News, “at last I fitted in with those auditioning me, ’cos that was Richard O’Brien in his teddy coat and his leather, and you don’t usually find people like that, who are auditioning you!”

“Over My Shoulder,” too, turned out to be an exquisite fit, as she explained to Scifi Online. “[It] suited the part of the usherette singing ‘Science Fiction.’ Richard played ‘Science Fiction’ for me on the guitar, at the audition. And he said: ‘Can you just sing along with this a bit?’ I was very nervous, and I tried to. I thought they were rock ’n’ roll guys and I didn’t know how to do all this.”

Clearly she made the right impression, though, and the feeling was mutual. When Quinn called her agent to announce that she wanted the part, he reminded her that she had not even read the script yet.

She didn’t care. The one original song she heard at the audition had convinced her that she wanted to be a part of the show, no matter how many other lines she might have.

In any event, she had quite a few. For within thirty minutes of the audition, she had not only been accepted for the role of the usherette, Miss Strawberry Time, she was also handed the somewhat more substantial part of Magenta.

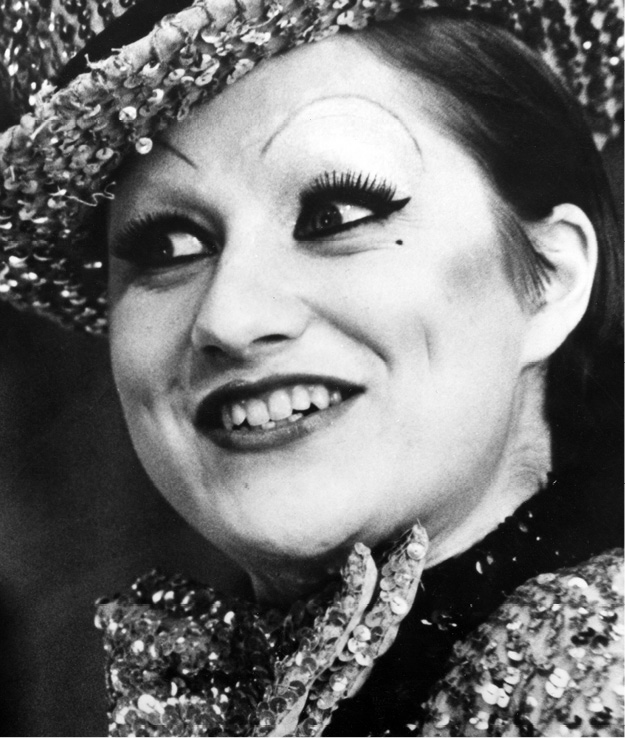

Call her Magenta—the magnificent Patricia Quinn.

© Daily Mail/Rex/Alamy Stock Photo

Jonathan Adams

Jonathan Adams was one of five members of the original London cast to be cast in The Rocky Horror Picture Show movie (after Curry, Quinn, O’Brien and Little Nell).

He was, however, the only one to take on a different role, after declaring himself bored with his original part, the Narrator. He was recast as Doctor Scott, one of the roles hitherto played by Paddy O’Hagan (the other was Eddie).

Born John Adams, he was initially drawn to acting as a child, watching The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Nevertheless, he followed a career in art for many years, and was already a twenty-eight-year-old schoolteacher when he decided to become an actor, changing his name to Jonathan Adams because the actors union Equity already had a John Adams on their books.

Even so, his acting career remained secondary to art for many years, minor roles in repertory interspersed with spells as a supply teacher. And then The Rocky Horror Show came along.

He auditioned for the role of the Narrator by performing “Baa Baa Black Sheep” at the piano, and so overwhelmed all present that O’Brien promptly went away to write a string of fresh scenes. Hitherto, there had been just one sequence in which the Narrator appeared, starkly emulating the intros to all those great British B-movies of the fifties—the ominously toned Edgar Lustgarten seated in an exquisitely furnished study, watching his own pottery bust spinning on a potter’s wheel. And you thought The Rocky Horror Show was weird!

The Lustgarten influence would remain heavy after O’Brien reworked the role. But now the Narrator was a part of the story.

Adams continued to work in the aftermath of The Rocky Horror Show, including the parts of Adam in the blockbusting television miniseries Jesus of Nazareth and Professor Marriott in the political sitcom Yes, Prime Minister.

He would also join a number of other cast members by securing a link to television’s Doctor Who (see Chapter 22), albeit a slender one. In 1974, shortly before he commenced filming The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Adams appeared alongside actress Katy Manning, Doctor Who’s Jo Grant, in Eskimo Nell, one of the highlights among a glorious run of low-budget British sex comedies that were themselves a cultural offspring of the 1970s’ loosening moral standards, and amidst whose company the Rocky Horror Picture Show itself is sometimes listed.

Adams certainly enjoyed the genre—he also turns up in the similarly themed Adventures of a Private Eye and Adventures of a Plumber’s Mate. But The Rocky Horror Show remained his best remembered role. In fact, the only question Adams ever asked when he was reminded of that fact was, “Which role are you thinking of?”

His Narrator and his Doctor Scott were equally memorable.

Julie Covington

The role of Janet Weiss, one-half of the lamb that was being led to slaughter, went to a performer who had not even considered a life of stagecraft until she went to Cambridge University. Julie Covington was more interested in singing than acting as a youth, and more interested in a career than either.

She appeared in the occasional school play (one was Giradoux’s Elektra), but she was also pursuing a future in education; she was studying to become a teacher, and it was for mere recreation that she also joined the Footlights, the university’s student theatrical troupe and the training ground for several generations of British comedians, actors and performers.

She just happened to become a key element within the next generation.

Working with writers Peter Atkin and Clive James, another member of the Australian arts diaspora, performing the material that they were writing, Covington established herself as one of the Footlights’s finest singers, and, in 1967, she and Atkin recorded the privately released LP While the Music Lasts, built around this repertoire.

She also came to the attention of Cambridge alumnus David Frost, now firmly established as a TV impresario, and that same year, Covington appeared on his then-current variety show, The Frost Report.

She performed at the 1967 Edinburgh Festival with a repertoire of jazz and Shakespeare; then returned the following year to appear in the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill play Mahagonny, for which she earned the inaugural Fringe Best Actress award.

That in turn led to an appearance in the pilot episode of director Tony Palmer’s new Twice a Fortnight series, featuring future Monty Python-ites Terry Jones and Michael Palin, and The Goodies stars Bill Oddie and Graham Garden; and by December, Covington was touring the United States with the joint Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

A second privately pressed LP, The Party’s Moving On, continued her collaboration with Atkin and James; it was sold primarily at the cabaret dates that she and Atkin were now playing, but a deal with EMI followed, and in 1970, Covington released her debut single, “The Magic Wasn’t There.”

Her first album, The Beautiful Changes (again comprising Atkin/James compositions), appeared in 1971, and that November, Covington made her professional theatrical debut in the original London production of the musical Godspell, at the Roundhouse. David Essex, who also appeared in the show, would later recruit Covington to sing backup vocals on his 1973 debut album.

Back on television, Covington enjoyed a stint reading children’s stories on BBC TV’s long-running Play Away and Jackanory shows—absolutely none of which, one imagines, prepared her for her next role, the ingenue Janet in The Rocky Horror Show.

Producer Michael White was delighted with her inclusion. Discussing Jim Sharman’s casting of the original play in his autobiography, he wrote, “With the whole world to choose from, he could not have done better than Julie Covington.”

Covington’s time in the play was comparatively short; she was already contracted to a role in Tony Richardson’s upcoming production Antony and Cleopatra long before she took up the scheduled three-week offer of Rocky Horror. She would be able to juggle the play’s eventual two-week extension, but that was the end of it. Her career, however, would continue on.

Christopher Malcolm

Where there was a Janet, of course, there had to be a Brad.

The late Christopher Malcolm was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, but grew up in Vernon, British Columbia, where his family emigrated in the late 1940s, taking advantage of a cut-rate £10 emigration scheme

His mother Paddy was an amateur theater fan (she is credited with introducing the English tradition of Christmas pantomimes to British Columbia), and her enthusiasm rubbed off on the boy. He studied theater at the University of British Columbia before then dropping out to help build and run the Powerhouse Theatre in Vernon.

He returned to England at nineteen, apparently in the aftermath of an unhappy love affair, and went to live with his grandmother, in Elsenham, Essex. She in turn introduced him to the son of one of her bridge partners, John Barton, an associate director at the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Malcolm auditioned, and joined the company in 1966. He remained on board for two years, working with some of the most accomplished directors in the field; then in 1968 he joined Charles Marowitz’s Open Space, in its original premises, a basement on Tottenham Court Road.

In 1970, Malcolm was cast alongside Martin Shaw in the Royal Court’s production of Michael Weller’s Cancer (aka Moonchildren), a Hair-like examination of contemporary teenage attitudes; and over the next few years he became a familiar sight through other productions at the theater (including The Unseen Hand, where he first met Sharman, Hartley and O’Brien), even before he auditioned for The Rocky Horror Show.

The role Malcolm took, of Janet Weiss’s strait-laced, white-bread boyfriend Brad (or “Ricky,” as he was known in the script at the time), was one that demanded all of his experience and observations from his time in Canada, the kind of “gee whiz” naïveté that the rest of the world sees as the epitome of the archetypal all-American boy.

The accent he had picked up in British Columbia certainly helped him out there, and throughout his run in the part, Malcolm was the show’s most unsung treasure—like Rayner Bourton (Rocky) and Julie Covington (Janet), his name never would become synonymous with the part that he created. But every subsequent player who has spouted “damn it, Janet” to a wide-eyed maiden owes Malcolm a major debt.

By the late 1970s, Malcolm had moved into production, beginning with another Richard O’Brien effort, 1978’s Disaster. But reviews were poor and Disaster quickly closed.

Other Malcolm productions proved more successful and included adaptations of Pal Joey, Steaming and Frankie and Johnny; and while his career was interrupted by a serious motorcycle accident in 1987, he continued working throughout his recovery. Other credits included Metamorphosis (with Tim Roth), The Pajama Game, successful stage adaptations of Footloose and Flashdance, and Our House, a production based around the music of the band Madness.

Malcolm returned to Rocky Horror in 1989, cofounding with O’Brien a new production company aimed at capitalizing on the show’s popularity, beginning the London Piccadilly Theatre’s revival. Later, he became the executive in charge of all subsequent worldwide productions—a post he retained until 2004, when, after fourteen years and fifteen productions, he resigned, apparently after a dispute with O’Brien over the show’s direction and future.

In a press statement announcing the separation, Malcolm wrote, “Personally, I am very sad that my journey has ended. The show in all its incarnations was a backdrop for much that has happened in my everyday life. . . . I am also very unhappy that it finished on a sour note with a very close friendship of such long standing being ended, leaving me having to withdraw from the company that I helped bring into existence.”

Back in early 1973, however, all that lay before him . . . it lay before them all.

The cast was complete, and Richard O’Brien, still astonished that his little piece of fun had taken on such life and roped in so many people, could finally sit back and relax in the knowledge that the cast, like the play, was complete.

Or was it?

Little Nell

If nineteen-year-old Sydney, Australia–born Laura Elizabeth Campbell had not been tap-dancing on the streets of London one morning in late 1972, the role of Columbia would never have existed, and The Rocky Horror Show would have lost one of its defining characters.

Campbell was nicknamed “Little Nell” by her father, a top Australian newspaper columnist writing for the Sydney Daily Telegraph—of course, he named her for the character in Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop.

She retained the nickname after her family moved to London in the early 1970s. There, she operated a small but flourishing boutique stall in London’s Kensington Market, bang next door to one run by the then-unknown Freddie Bursali . . . Freddie Mercury to be.

“Freddie was a sweetie pie,” she recalled for retroladyland.blogspot.com. “He told me he was in a band and I thought, ‘yeah, well, you’re working in a market, so the band’s obviously not doing that well.’ We would have a laugh as he sold his groovy platform boots. I warned him that if he ate so much as a donut, his trousers would split. Good Lord, they were tight.”

She also earned money working as a street musician, or busking in the local parlance, to the crowds outside the theater where Jesus Christ Superstar was playing, which is where Sharman saw her, executing the tap-dancing routines that she learned as a child. “I’d actually met Jim before in Sydney,” Campbell told ripitup.com.au, so they got talking and he learned she had yet another job, working as a soda jerk at Small’s, a restaurant in fashionable Knightsbridge, where she would also occasionally brighten her customers’ day with an impromptu burst of dance.

“[Jim] and Richard O’Brien and Richard Hartley all came to where I was working . . . . They arrived there and I was dressed in 1930s clothes, which was how I always dressed at the time, with bob hair and satin shorts and a polka-dot blouse and tap shoes. And I served them by tap dancing to their table.”

Only then did Sharman inform Richard O’Brien that he needed to write a new character and songs into The Rocky Horror Show specifically to accommodate her—including, incredible though it may now seem, “The Time Warp.” Sharman wanted a tap dance number, and that is what he received.

“I probably said yes to the part . . . as I would have said yes to any role,” Campbell admitted to retroladyland.blogspot.com. “I was very young and desperate to be an actress. They played me a couple of songs from the show in the cafe, I seem to remember, and they sounded great.”

Under such circumstances, the role of Columbia, the groupie who has attached herself to Doctor Frank-N-Furter, could easily have felt like a rush job. Instead, O’Brien wove her seamlessly into the action, and Little Nell did the rest.

Little Nell Campbell, tap-dancing groupie superstar.

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation/Photofest