Hypocrisy, as the Narrator might say, from his well-appointed library filled with charts, maps and pointers, is rarely an easy fault to forgive.

It is the politician voting down a civil liberties bill despite indulging in the exact same practices (and more) in his very own private life.

It is the parent who wore out the Kama Sutra before even graduating high school, who then locks his or her own children down like a convent in a Viking raid.

And it is the critic who spends his entire career nailing new performances for their lack of originality, then condemning one more for being too far-out.

The Rocky Horror Show has never been a stranger to hypocrisy.

Fortunately, it has always been equipped to puncture it, with its ongoing and unending success certainly serving up the most exquisite riposte to those writers who hammered it for sundry perceived faults in its infancy. As producer Michael White said, even at the Theatre Upstairs, The Rocky Horror Show felt critic-proof. History has merely layered more armor on it.

But nowhere were those defenses to be more desperately called upon than when the show hit the United States. By the end of 1975, a year that boded so well for the show, the very name of The Rocky Horror Show would be all but synonymous with cinematic disaster and artistic despair.

Although it was great when it all began. . . .

We’re Gonna Make a Movie

The Rocky Horror Show had just relocated to the King’s Road Theatre, and was still less than six months old, when American record and movie producer Lou Adler dropped by, in the company of his then-girlfriend, actress Britt Ekland.

His attendance alone was considered something of a coup. Still only thirty-nine years old, Adler’s list of music industry achievements was already one of rock’s most storied. A hit songwriter since the late 1950s; producer of such heroes as Sam Cooke, Scott McKenzie, Barry McGuire and the Mamas and the Papas, he was a savvy businessman, too. In 1964, he launched Dunhill Records; three years later, he sold it for $3 million. In 1967, he founded Ode Records, and oversaw Carole King’s rise to singer-songwriter fame.

He was among the organizers of the legendary 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, introducing Jimi Hendrix and the Who to America at large. Now he was eyeing up The Rocky Horror Show and talking about transforming it into a motion picture.

“No sleep!!” he recalled in the liners for the show’s fifteenth-anniversary CD box set. He had just flown into London from Los Angeles, and was certainly not expecting Ekland to have arranged for them to see a show that same evening.

“Jet-lag!! BAM!!! The Rocky Horror Show. It cut like a knife. From the first moment I entered the theatre, cobwebs, flashlights, white-faced ushers and the opening chord of ‘Science Fiction,’ I had the feeling you get when you see or hear something very special for the first time.” Adler’s celluloid intentions did not, initially, particularly interest O’Brien—who, totally by chance, was playing Frank-N-Furter that evening, after Tim Curry called in sick.

Neither was his disdain in any way a personal slight toward his visitor. But O’Brien had heard such words so many times before, from any number of other lovestruck viewers; and, like so many other stage performers and writers, he was utterly indifferent to that vein of lazy snobbery that insists a story’s not a story until it’s been made into a film—a process that usually involves, in no particular order, sucking out all of the joy that made it “worth” committing to celluloid in the first place; filling the key roles with box office “certainties,” and then rewriting the whole thing because it doesn’t translate.

Later in the decade, when Hair was finally filmed, the plot had been so utterly altered that writers James Rado and Gerome Ragni were moved to insist that any resemblance between their creation and the movie, beyond the songs, names and title, utterly eluded them. And they weren’t alone.

But there was also a third factor to be taken into consideration, and that was the fact that The Rocky Horror Show was itself a parody of the movies. Turning that parody back on itself, if not a recipe for disaster, was at least a sleight of hand too far. It could very easily backfire.

Adler, however, would not be discouraged. Instead, he turned his attention to Michael White, discussing the possibility of transferring the play to Los Angeles and allowing its inevitable success in that city to stir up the necessary interest from Hollywood.

In the back of his mind, he was already considering 20th Century Fox as the ideal studio to handle the production, while fears that an American production might lose some of the edge that the London play rejoiced in were allayed—once he saw the show again, and caught Doctor Frank-N-Furter as nature intended—by his suggestion that Tim Curry should be retained for the show.

As for where it could be staged, Adler already had that question answered. Just months earlier, in partnership with fellow industry bigwigs David Geffen, Peter Asher, Elliot Roberts and Elmer Valentine, Adler had established a brand new club on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip.

Taking over what had once been a strip club called the Largo, the Roxy Theatre opened on September 23, 1973, with a three-night stand by Neil Young. Comedians Cheech and Chong, rocker Jerry Lee Lewis and country songstress Linda Ronstadt had all played sold-out engagements at the club since then, and in December, Frank Zappa passed through to record much of his latest live album, the sensibly titled The Roxy and Elsewhere. The British band Genesis wound up the venue’s 1973 itinerary; Joe Cocker would kick off 1974.

Neither was the music the venue’s sole attraction. The new kid on the Hollywood block it may have been, but upstairs from the Roxy lurked a private members club called the On the Rox. Which was where, according to the hottest industry scuttlebutt, the likes of John Lennon, Alice Cooper, Keith Moon and Harry Nilsson cavorted the night away.

Many venues claimed to offer a “captive audience.” The Roxy could supply captive celebrities, too.

White took the bait, Curry took the plane ticket. The Rocky Horror Show was going international.

Meanwhile, Back in London

Curry’s departure at the end of 1973 saw The Rocky Horror Show undergo its fourth change of cast (fifth if you counted the short-lived Andy Bradford), and its most crucial, and potentially damaging, one yet.

Rocky was replaceable. Janet was replaceable. Even Magenta turned out to be replaceable.

But Doctor Frank-N-Furter?

Maybe it wasn’t quite like the Rolling Stones shedding Mick Jagger. But Genesis losing Peter Gabriel? The Who going on without Keith Moon? Some things were just unimaginable. But they happened, all the same. The show had to go on, and Welsh actor Philip Sayer was the man selected to ensure that it did.

And it has to be said. Sayer pulled it off with such aplomb that many theatergoers had no idea that a star had even gone astray.

Born and raised in Swansea, where he worked with both the Little Theatre and the Grand Theatre while still in high school, Sayer was accepted into the Royal Academy of Music and Dramatic Art in 1963.

In 1970, he made his West End debut, appearing as Guibert in Robin Phillips’s acclaimed production of the medieval Abelard and Heloise (Keith Michell and Diana Rigg played the title roles). He followed that with a stint in The Dirtiest Show in Town, and by 1973, he was touring the world with the Royal Shakespeare Company, before returning to London in time to claim the role of Doctor Frank-N-Furter.

He remained with the show for no more than eight months (some sources claim considerably fewer), before a back injury—supposedly induced by having to totter around in high heels for so long—forced him to quit.

(He would be replaced by the patiently waiting understudy “Ziggy” Byfield, an actor who was at pains, by the way, to assure all comers that his distinctive nickname had nothing to do with David Bowie. He’d been landed with it years before that, after constantly mishearing another friend’s name, Zekey.)

Such accomplishments notwithstanding, Sayer’s subsequent career was largely that of the ubiquitous “him out of thingy,” a face that one recognized (particularly on British TV), but whose name was rarely on the tip of the tongue.

He never failed to impress, however. On the big screen, he was the monster in Xtro and Kronk in Shanghai Surprise, while he was instantly memorable (and utterly despicable) as an early, unnamed, victim of Catherine Deneuve’s gorgeous vampire in The Hunger. He was a regular in the six-part television drama Inside Out, and he played Paul of Tarsus in the 1985 biblical epic A.D.

Stricken by cancer, Sayer passed away in 1989; but it is a mark of the deep love and respect in which he was held that in 1992, Queen guitarist Brian May—who knew the man only from the stories told by mutual friends in the entertainment industry—wrote the song “Just One Life” in his honor.

Remodeling Magenta

Quinn’s departure, too, gave the production team considerable pause. Indeed, as difficult as it was to find a suitable and (even more crucially) believable replacement for Curry, Magenta’s shoes were just as awkward to fill and, in many ways, even more fraught with danger.

So unconventionally beautiful, so radically sensual, and so brilliantly, delectably edgy, Quinn had created an archetype without parallel in the theater. Even Curry, at times, paled alongside her. And now she was taking it away again, as the BBC recruited her to play suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, the daughter of the British movement’s founder, Emily, in the six-part TV series Shoulder to Shoulder.

Again, it was time to replace the irreplaceable, and once again the vacancy was filled, by her understudy, Angela Bruce.

Seven years Quinn’s junior, Angela Bruce was born in Leeds, in the northern English county of Yorkshire, in 1951, the daughter of a West Indian father and a white mother.

She was, at the time, still at the outset of her career—now we know her as one of Britain’s most versatile character actresses; even at the time, however, her talent was evident, particularly throughout her time as understudy, covering all three female roles, on The Rocky Horror Show. And since that time, Bruce has played major recurring roles in a variety of shows, including the characters of Gloria in Rock Follies (see Chapter 13), Sandra Ling in the hospital drama Angels, Janice Stubbs in the long-running soap opera Coronation Street, and Chrissie Stuart in Press Gang. She also followed Patricia Quinn into episodes of Hammer House of Horror and Doctor Who (see Chapter 22).

A new Brad, too, would soon hove into view, as Christopher Malcolm moved on. James Warwick was best known at the time of his casting for the role of Dan Walters in the British children’s TV series The Terracotta Horse; and following his time with The Rocky Horror Show, he, too, joined the cast of Rock Follies, and would also surface in episodes of Doctor Who.

He remained active onstage, too, appearing on Broadway in An Ideal Husband, and playing King Arthur in the American touring production of Camelot, before moving into directing. In 2007, Warwick was elected interim president of the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, Los Angeles Campus; and in 2009, president of Theatre of Arts in Hollywood.

Hollywood Highs

Rehearsals for the Roxy production were tense. To keep the cast on their toes, the returning Jim Sharman decided not, initially, to distribute scripts, or any other indication of the true nature of the play, to its participants.

Few, if any, of the people auditioning for the play had any concept of what The Rocky Horror Show was about; they auditioned because there was an audition being held. In Hollywood, that’s what you do.

Sharman intended keeping them in the dark, offering up little more than a handful of songs to sing, allowing all concerned to sink into the belief that this Rocky Horror Show was nothing more than a lighthearted parody of old sci-fi and horror movies.

Until the day Tim Curry turned up in full Frank costuming and gave them a taste of “Sweet Transvestite.”

Meat Loaf, one of the young Americans hired to perform in the play, picks up the story in his To Hell and Back autobiography.

We’re finally ready to rehearse Curry’s entrance, but we still haven’t seen him. Doors in the back of this little theater open, and a guy with big black hair and a leather jacket comes walking down the aisle singing “Sweet Transvestite.” As he gets closer, we see that he’s got a garter belt, fishnet stockings and enough make-up for a cosmetics counter.

I’m sitting next to Graham Jarvis, the show’s Narrator. I turn to him and say “I’m leaving!” I walk across the street against the light and get a ticket for jaywalking. Graham followed me out and I asked, “what is this? What’s going on? These people are nuts. I’m not doing a drag show.”

Two previews would prepare—or otherwise—The Rocky Horror Show for Los Angeles, and Los Angeles for The Rocky Horror Show, before the play premiered on March 21, 1974. And if you really took its B-movie background to heart, the song that all but closed the show had never been more perfectly poised.

It had gone home.

Greasing the Cast

No less than its London counterpart, the Roxy Theatre production drew its denizens from the shadows: Bill Miller, playing Brad; Bruce Scott, brilliant as Riff-Raff. Tim Curry was a complete unknown in American terms at the time; and any prospective audience members scanning the program for recognizable names would instead have seized upon Jamie Donnelly, in her joint roles as Magenta and the newly renamed Trixie the Usherette. (For some unknown reason, Miss Strawberry Time just didn’t have the authentic drive-in ring to it.)

Jamie Donnelly is probably best remembered as Jan, one of the original Pink Ladies in Grease, first the original Broadway stage show and then the subsequent, monstrous movie.

Her performances in both the Roxy and Broadway productions of The Rocky Horror Show probably come a close second, however, while Rocky trivia freaks also smirk at the memory of her replacing the Rocky Horror Picture Show’s Brad, actor Barry Bostwick, in the title role of a musical version of Tarzan.

However, Donnelly’s career reaches back to the mid-1960s, when she originated the role of Lulu in the Broadway production of Kander and Ebb’s Flora, the Red Menace—where she was also understudy for Liza Minnelli’s title role.

Other notable parts included turns in Joel Grey’s George M; the stage biography of Rodgers and Hart; and You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown; while soap fans might well recall her as Dusty Maguire in The Guiding Light. She has also worked as an acting coach.

In the role of the Narrator, Canadian Graham Jarvis was one of those faces, if not names, that everyone recognized, whether from a long career spent in television (appearances in Naked City, Route 66, All in the Family, M*A*S*H) or middling roles in a succession of movies—Alice’s Restaurant (where the cast also included an American actress named Patricia Quinn), The Out of Towners, Cold Turkey, What’s Up, Doc? and more. He was Charlie Haggers in Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, and, shortly before his death (from multiple myeloma in 2003), he was absolutely fabulous as the foul-mouthed funeral director Bobo in Six Feet Under.

But he also introduced the United States to the Time Warp. And for that, we thank him. Maybe.

Tap-dancing her own way through that number was Boni Enten, the Roxy’s own Columbia.

As a teenager, Enten launched her career at the Schubert Theatre in 1965, playing an unnamed “urchin” in English actor Anthony Newley’s The Roar of the Greasepaint, The Smell of the Crowd. Further small parts followed, including a role in the movie Pigeons, before she arrived in the New York cast of Oh! Calcutta! in 1969; and from there, The Rocky Horror Show. Enten would later appear in Pal Joey, while returning to the cinema via 1977’s Kentucky Fried Movie.

A Man Named Meat

Of course, The Rocky Horror Show is a musical as well as a stage show, and unlike the London presentation, where the cast’s musical abilities were more or less uncovered by happy accident, the Roxy production was more exacting. By the time Meat Loaf was cast in The Rocky Horror Show, the former Marvin Lee Aday had already been performing around Los Angeles for some three years, fronting a band called Meat Loaf Soul.

They were a memorable act, although not always through their own actions. According to one legend, they cleared the club at their very first gig, when their smoke machine malfunctioned. They recovered to become regular openers for a host of local and visiting superstars, but neither Meat Loaf Circus nor such subsequent names as Popcorn Blizzard and Floating World made much of an impression (although the former did release a single), and, in 1969, their frontman joined the cast of the Los Angeles production of Hair.

He remained there for around a year, before he was lured back into the world of gigs and records by Tamla Motown, as the venerable Detroit R&B label commenced one of its periodic pursuits of the mainstream rock audience. They paired him with another recent recruit, singer Shawn Murphy, aka Stoney, and were immediately rewarded when the couple’s first single, “What You See Is What You Get,” made the lower reaches of the Top 100.

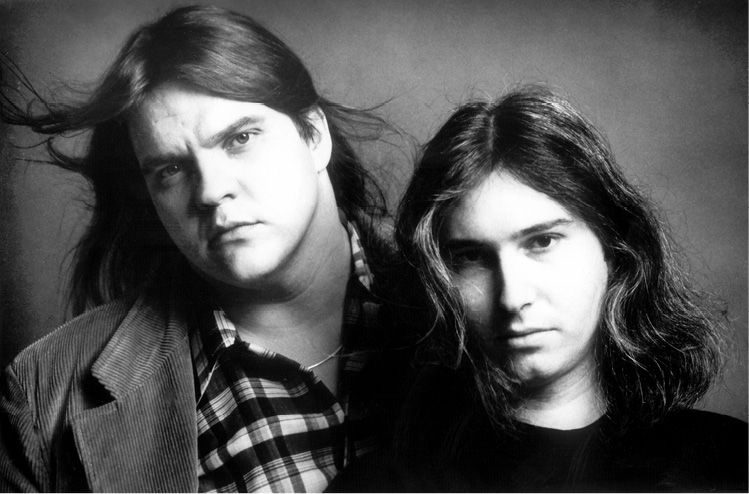

The movie Eddie, Meat Loaf (left), with musical collaborator Jim Steinman.

Photofest

But an album, titled Stoney and Meatloaf, did little, and Meat Loaf returned to the cast of Hair, now on Broadway. From there, he shifted to the Public Theatre’s production of More Than You Deserve, and later, As You Like It with Raul Julia. By the end of the year, he was in Washington, D.C., performing in a short production of Rainbow in New York, and then came the invitation to audition for The Rocky Horror Show.

His musical career would not be put to one side. Throughout his time with the play, Meat Loaf and his friend Jim Steinman, a musical arranger and composer he met during his time with More Than You Deserve, were scheming what would not only become Meat’s first solo album, Bat out of Hell, but is also still ranked among the best-selling LPs of all time. And the influence of one would certainly become apparent in the other.

Meanwhile, Meat Loaf would also have a profound effect on future portrayals of one of his characters, Eddie. Having accustomed himself to the “drag” show, and realized that he could get one of the biggest laughs of the evening by draping his plus-sized thighs in fishnets and heels, he told Fuse TV in 2014, “Everyone else who had played Eddie over in England had tried to do an Elvis impersonation. That’s what they said to me when we started doing it out in LA, but I looked at them and go, ‘Why would you want an Elvis impersonation? Why wouldn’t you want Eddie to be his own human being?’ They go, ‘Well, okay.’”

It was probably just as well they did, because that summer, Elvis Presley himself dropped by to watch and, afterwards, meet the cast. “And that’s what Elvis talked to me about,” a still awe-stricken Meat Loaf continued. “He goes, ‘Well, I hear everyone wants to do an Elvis impersonation, but you didn’t.’” To which Meat Loaf, speechless with shock at even meeting the King, could only reply “No, because there’s only one you, and only one me.”

“That’s all I said to him,” he mourned.

A Rocking Rocky

In the role of Rocky, Richard Kim Milford was another graduate of Hair, joining the original Broadway cast in 1968, following stock theater roles in Chicago and a stint in Henry Sweet Henry.

He was cast in the same role Tim Curry played in London, Woof, while he also followed in Richard O’Brien’s footsteps with a couple of parts in Jesus Christ Superstar—although Milford was certainly a few steps further up the food chain. He played both Jesus Christ and Judas Iscariot in the musical’s first American touring production.

His role in Hair was also sufficient to earn him a one-off record contract with Decca, for the 45 “Muddy River Water,” and Milford continued his musical career first with Eclipse, formed from the remnants of Genya Raven’s Ten Wheel Drive; then when he was recruited to the hard-rock supergroup of (Jeff) Beck, (Tim) Bogart and (Carmine) Appice, when they re-formed in summer 1972.

With Milford proving a salamandrine performer behind closed doors, rehearsals in the UK went well, and a three-week US tour was set to open in Pittsburgh on August 1.

The British New Musical Express caught up with the band as it put the finishing touches to the show.

“Kim Milford is the kind of lead singer girls will go crazy for,” wrote Danny Holloway. “[He’s] definitely on a par with Robert Plant. His long blond hair passes his shoulders, fully encompassing his delicate baby face. He’s an excellent shouter and will most likely present a focal point for on stage activities.”

Neither was Milford at all phased by the task ahead of him, a comparative unknown suddenly fronting one of the loudest, heaviest bands around: “I’m sort of used to it because I used to have a lot of that when I replaced people in shows.”

However, after just six shows, he was fired. What looked and sounded great in rehearsal simply did not translate to an auditorium full of screaming hard-rock fans, and Beck’s dissatisfaction with the way things were going seemed etched on his face every night.

Finally, Beck snapped. According to legend, the notoriously quick-tempered guitarist actually sacked Milford backstage at the Chicago show, during the break between the main set and the encore, with Milford’s own mother looking on. The band returned to the stage without their singer, and the next time they performed live, Milford had been replaced in the band by singer Bobby Tench.

Shaken but undeterred, Milford promptly formed a new band of his own, Moon, and in 1973 they featured in the movie Rock-a-Die Baby. The singer was also reported to have recorded (if not released) a solo album around this time, appropriately titled Chain Your Lovers to the Bedposts.

Having followed The Rocky Horror Show when it transferred to Broadway, Milford was passed over for a role in the movie. But he was reunited with Meat Loaf in the short-lived Shakespearean boogie-fest Rockabye Hamlet, and in 1978, he starred in the science fiction movie Laserblast, described by writer Cynthia Dagnal-Myron, a personal friend of his, as one “of the worst movies, ever . . . [rivaling] Plan 9 from Outer Space for sheer ‘unwatchability.’ It is so bad that it has become a cult film sought after by collectors for being so bad.”

But he composed the soundtrack to a 1979 adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, performed at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and in 1980 he would return to The Rocky Horror Show for the latest revival’s North American tour.

Milford continued active through the 1980s; he passed away on June 16, 1988, several weeks after undergoing open-heart surgery.

Jo Mama Janet

Abigale Haness, the original Stateside Janet, was likewise hired for her abilities as a vocalist, as opposed to any acting experience. Destined to become one of the Los Angeles session scene’s most accomplished backing singers, Haness was then best known as vocalist with Jo Mama, a slinky, funky rock band formed in 1971 by her then-husband Danny Kortchmar, and former Clear Light organist Ralph Schuckett.

Certainly their self-titled debut album boasts one of the sexiest “Great Balls of Fire” ever waxed, with Haness an irresistible force who peaks with the sensuous “The Word Is Goodbye” and the folk hoedown “Cotton Eye Joe,” immaculately transformed into blue-eyed soul.

A second album followed before Jo Mama broke up, but Haness remained a presence on the Los Angeles scene; and though she too was passed over for The Rocky Horror Picture Show, when it came to cutting the soundtrack, it was Haness’s vocals that came out of actress Susan Sarandon’s mouth.

Rockying the Roxy

No less than it had in London, when it hunkered down in Chelsea, The Rocky Horror Show found itself on fertile soil. Hollywood was home, after all, to many of the movies that the stage show referenced; in fact, the play hit town around the same time as former Beatle Ringo Starr’s latest LP, Goodnight Vienna, with its cover photo directly referencing The Day the Earth Stood Still, the first movie mentioned in the first song of the show.

That coincidence alone was sufficient to grab a little attention, while once again the word that grapevined out from the previews would quickly draw the curious in.

True to Adler’s word, and the Roxy’s reputation, the city’s great and powerful naturally descended on the venue, although Keith Moon, drummer with the Who, is the guest whom most of the cast remember the fondest. Every night that he attended the play, and it became a regular part of his routine, Moon would arrange for nine bottles of champagne to be left on the front of the stage, one for each member of the cast.

Plus, of course, Hollywood itself has always taken a freak show to its heart.

The Rocky Horror Show would remain at the Roxy for a total of nine months, playing until January 5, 1975, and being interrupted just once, when the New York Dolls came to town for a performance at the Roxy in June 1974. They were, perhaps, the only band in the land whose performance, and gift for sleaze and shock, could match The Rocky Horror Show for rocking outrage.

Behind the scenes, too, things were moving fast.

The moment that Adler was certain the play was the success he had always envisioned, he invited the head of 20th Century Fox, Gordon Stulberg, to the Roxy to see the play.

Adler had already taken note of the play’s most avid fans, the people who seemed to be turning up night after night to watch (and in those days, that is basically all they did . . . watch) the show; would make a point of introducing himself to them, occasionally offering them free seats for the evening, complimenting them on the costumes that a few of the most daring acolytes were affecting.

Now his attentions came to fruition. A private performance of the musical was set up for Stulberg’s benefit, with a specially invited audience of Rocky Horror’s most vociferous local fans to add further atmosphere to the proceedings. Adler later admitted that he never did discover if Stulberg truly understood what he was watching. But the movie mogul certainly appreciated enthusiasm. And this audience was wild.

A movie deal was in the bag, but Adler’s ambitions did not end there. Now he set his sights on Broadway. There, he declared to whoever was listening, The Rocky Horror Show would become the biggest thing since Jesus Christ Superstar.