With filming now complete, Tim Curry returned to the United States for The Rocky Horror Show’s Broadway opening, at the 967-seat Belasco Theatre on March 10, 1975.

Compared to past productions, Broadway required a lot of The Rocky Horror Show—or perhaps, that should be the other way around. The Rocky Horror Show required a lot of Broadway, beginning with the extensive remodeling of the theater itself.

A beautiful neo-Georgian structure opened in 1907 as the Stuyvesant Theater, the playhouse was renamed for its original manager, impresario David Belasco, in 1910, and it swiftly became renowned as one of Broadway’s most daring theaters.

Himself a fierce supporter of the so-called Little Theatre movement, Belasco ensured the venue was designed as the most intimate, private setting imaginable. Tiffany light fixtures, murals by American Ashcan School artist Everett Shinn, the most up-to-date electronics and hydraulics, the Belasco was the theater that other owners aspired to emulate.

It was at the Belasco that Tallulah Bankhead starred in the first-ever production of Clash by Night, in 1941; there that a young and unknown Marlon Brando was first proclaimed a star-in-waiting, in 1946, appearing in Truckline Cafe.

It was the original home, in 1923, of Laugh, Clown, Laugh, the Belasco production that was eventually essayed into the Lon Chaney movie of the same title; and almost fifty years later, the Belasco hosted Oh! Calcutta!, and survived even that experience intact.

Preparations for The Rocky Horror Show, however, saw many of the theater’s original fittings either dismantled or destroyed by the workmen, outraging Broadway purists and historians even as the new show’s backers argued that the play would more than repay the damage with its success.

Or not. According to Broadway legend, among the theater’s longest-serving guardians was David Belasco himself—dead since 1931, but still keeping a solicitous eye on his old pride and joy.

His spirit had frequently been seen benignly looking on, or passing through during other productions, usually clad in the clerical collar and cassock that the so-called Bishop of Broadway enjoyed sporting while he lived.

Sometimes, he would seem about to speak to actors who passed him in the backstage area; other times, he would simply watch silently from the balcony. And occasionally he was accompanied by a second figure, a lady in blue who, it was said, had been his consort toward the end of his life.

Sightings of these spirits increased noticeably as the remodeling of the Belasco got under way, accompanied by what was usually described as a sense of sadness at the senseless demolition of so much of the old building’s fabric.

Sadness that turned, eventually, to rage.

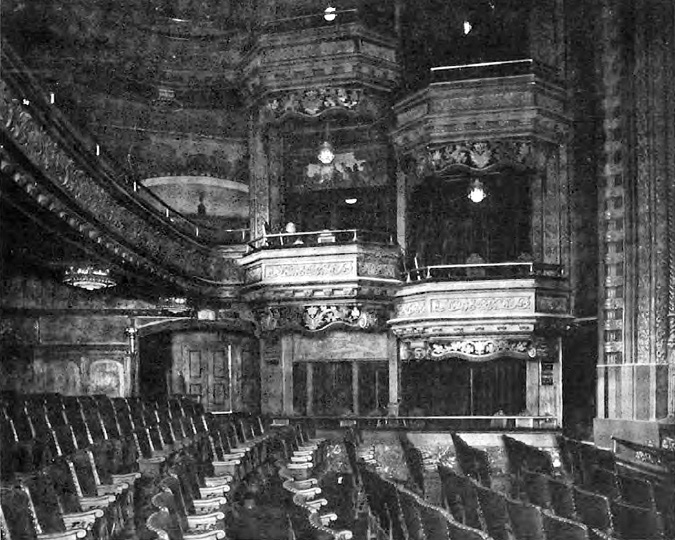

The Belasco Theatre on Broadway before Rocky demanded its renovation.

Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Weird, Preposterous and Distinctly Charmless

Maybe Belasco only cursed this particular production. Perhaps he cursed The Rocky Horror Show itself. But for a while—only a short while, in the overall scheme of things, but it must have felt like an eternity at the time—Rocky Horror himself could not have got arrested in New York City. (The Belasco was finally returned to its original splendor in time for the opening of the play Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, a full thirty-five years later.)

The full Roxy cast was scheduled to make the transfer across country, including the returning Tim Curry and Meat Loaf, although there would ultimately be a place for Richard O’Brien as well, taking over the role of Riff-Raff after his Roxy counterpart, Bruce Scott, was injured in another play.

Superstitious mumbo-jumbo notwithstanding, there appeared to be no reason at all why The Rocky Horror Show should not simply pick up where it left off in Hollywood.

But superstitious mumbo-jumbo maybe should be granted some credence, after all.

Three previews met with an uncertain response, audiences reacting not with gleeful shock and conspiratorial laughter, but with a blank-faced silence that nothing could penetrate.

Alterations were made. Frank’s grand entrance up the ramp perished, after it was realized (during the first preview) that viewers on the balcony would not be able to see it. But nothing worked, nothing helped, and when Curry was handed a guest appearance on The Today Show the morning after the first night, it quickly transformed into trial by ordeal. As he told LosAngelesOnline in 2015, “They read the reviews—which were appalling. That brought me down. It was very cruel.”

Even thirty-five years later, with The Rocky Horror Picture Show reestablished on the Broadway stage and, this time, a major success, New York Post reviewer Clive Barnes still recalled “an ill-advised and pointless cabaret [that] looked weird, preposterous and distinctly charmless.” Although he wasn’t that keen on the remake either, describing it as “over produced . . . encrustation [piled] upon ornamentation. For the unconverted, such as myself, it is all too much.”

Anybody who cast an eye across the ocean to where a movie of the same benighted production was now on the horizon must surely have wondered how low it, too, could sink.

In hindsight, Curry at least took some solace from the failure of the Broadway production. Throughout the show’s run, he admitted that he had probably never been so unhappy in his life, knowing that audiences were attending, for the most part, only to discover whether or not the show really was as appalling as the critics made out.

By the time he returned to England, so much earlier than he had ever anticipated, all he could do for the next month was retire to his room and nurse a bottle of vodka, periodically sending out for submarine sandwiches and doing absolutely nothing else.

At which point he realized that no matter how many knives had been stuck into his back as he walked the Belasco stage, he was still alive, and still hungry for work. He had been through hell and had come out the other side. He would never be hurt by another review again.

Although there would be many more that would have a go.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show premiered at the Rialto Theatre, in London’s Leicester Square, on August 14, 1975.

The venue had been selected with care. One of the West End’s oldest surviving cinemas, the Rialto was also one of its most resonant, Until it was wiped out by a German bomb in 1941, the Rialto’s basement had hosted the Cafe de Paris, one of the city’s hottest nightspots. Piercing the roof, the bomb passed straight through the cinema auditorium, traveling down a ventilation shaft to detonate inside the crowded nightclub below. Thirty-four people were killed, including bandleader Snakehips Johnson.

Since that time, successive owners had done much to restore and retain the building’s historic aura, and that was the atmosphere that it was hoped would envelop tonight’s audience of stars and critics. For certainly there was a sizable crowd of onlookers and media waiting outside the cinema both before and after the screening.

Patricia Quinn gave them something to look at, too, modeling her appearance on 1920s actress Clara Bow in the movie Red Hair—underwear slip, stockings and garters, topped off with Ms. Bow’s own coiffure.

Clara Bow in the movie Red Hair, the inspiration behind Patricia Quinn’s breathtaking costume at Rocky’s London movie premiere.

© World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

But whereas the crowds had been cheering beforehand, by the time the show was over, the mood had changed considerably, both among the audience and the cast. While the guests drifted silently off into the night, the actors were left to stand around like mourners at their own laying out. The first reviews had not even been phoned in yet, and they already knew that the movie was a flop.

Britain was bad, but worse was to follow.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show received its American premiere at the United Artists Theater in Westwood, Los Angeles, on September 26, 1975, and, like the Roxy production before it, it proved an immediate local success.

Rock musician Joan Jett—or plain old Joan Marie Larkin as she was at the time—was one of the movie’s biggest, and earliest, fans. Already a denizen of the English Disco, the legendary lair from which local scene-maker Rodney Bingenheimer schemed transforming the whole of Los Angeles into one vast glam-rock paradise (and where the Roxy cast version of “Sweet Transvestite” was in regular rotation), Jett was fifteen years old when Rocky Horror Picture Show opened at the cinema, and an immediate convert.

“I’m a fan, very much so,” she told journalist Mary Campbell. “I’d say it was pretty instrumental in me figuring out who I was. It was a very formative time in my life.”

Her life, and those of several others. Under the aegis of rock entrepreneur Kim Fowley, Jett had just been recruited to a new band, the all-girl—all teenaged girl . . . . more or less jailbait, in fact—Runaways, but it was still very early days.

They had more nerve than songs, and absolutely no image whatsoever. So when Jett suggested they head out to see The Rocky Horror Picture Show, they listened. And when she suggested that they go and see it again . . . and again . . . and again . . . they listened to that as well.

“Me and my friends would go to see it all the time,” she recalled. “We went a lot.”

And Doctor Frank-N-Furter’s corset was always there to grab their attention, in the same way that corsets always seem to focus people’s minds. Which may be why the Runaways singer, Cherie Currie, reclaimed the garment from her near-namesake’s torso and started wearing one for her own performances.

In terms of pop-cultural iconography, Currie’s corset is today as well remembered as . . . well, as the other Curry’s corset.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show was happy in Hollywood, then. It had allies there, and acolytes, too. It made friends and influenced people. A very different fate awaited it on the national theater circuit, however. Eight opening cities had been selected to screen it, and all eight rejected it with audiences so tiny that not a single, solitary theater was willing to keep the movie on. Then came the news that the movie’s New York opening, scheduled (of course) for Halloween, had been canceled before the film cans even arrived in the city.

Desperate times called for desperate measures. Boldly striving to improve the movie’s American reception, the distributors decided to send it out with Brian DePalma’s masterful Phantom of the Paradise, a rock ’n’ roll updating of the old Phantom of the Opera, with William Finley as the rock icon who is shortly destined to become the Phantom, and Jessica Harper as Phoenix, an aspiring singer who becomes his girlfriend (and who later appeared as the older Janet Weiss in Shock Treatment).

It’s a fabulous movie, jam-packed with a glam-rocking soundtrack that really wasn’t that far removed from Rocky Horror’s. But there was one fatal flaw to the marketing move. Phantom of the Paradise, too, was in the process of crashing abysmally, and so audiences were faced with a quite remarkable choice. Take their chance on two flops for the price of one? Or go spend their evening on something else entirely?

The majority (to their eternal disgrace—has there ever been a greater double feature than this?) chose the latter, and by Christmas, it felt like the show was over. Rocky was a horror, and that was the end of it.

Or it would have been, had it not been for one man paying attention.