11

The Biggest Dirty Show in Town

It was not only the songs, the performances and the costumes that were applauded. Patricia Quinn later recalled wondering why Little Nell seemed to win a roar from the audience every time she moved, whereas the rest of the cast merely received clapping or laughter.

Then she realized. Purposefully or otherwise, the diminutive Columbia was flashing her nipples at the crowd; “playing to the dirty raincoat brigade,” as Quinn put it. And there seemed to be quite a few of them turning up to every performance. Word of the corset and the show’s content was spreading as fast through London’s sleazy underbelly as it was through the theatrical glitterati.

Meanwhile, demand for the minuscule number of available seats was not simply swamping the box office. Ticket agencies in the West End, hitherto accustomed only to juggling admission to the biggest theaters in town, were staggered by the number of requests they were receiving for a venue that had previously scarcely registered on their books. Even London’s traditionally so-resourceful black market, the ticket touts who never seemed to be at a loss for a few good seats (at a price, of course), was left floundering.

Astonished but gratified, the Royal Court agreed to extend The Rocky Horror Show’s original three-week run to five, until July 21 (a new production, Sweet Talk by Michael Abbensetts, was scheduled to premiere on July 31, 1973). And still that wasn’t enough.

Soon, producer White was all but begging O’Brien to allow him to transfer the show to the West End, to one of the larger theaters in the center of London, where it could play to everyone that wanted to see it.

Someplace where the dressing rooms were not essentially cupboards, and where Patricia Quinn’s transformation from usherette to Magenta did not need to be executed in the tiny office that latecomers were still using to get into the theater. Where she wouldn’t be interrupted, mid-change, by ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev passing through on his way to his seat.

O’Brien turned White’s supplications down. The Rocky Horror Show demanded intimacy and, in its own way, obscurity. It was not some grand, ritzy production to be staged in a venerable bastion of the theatrical mainstream. It was a backstreet guerrilla operation, lurking in the darkness on the edge of town. You needed to want to see it before you could attend, and to seek it out intentionally; not just tumble in to the box office on a passing whim, to catch a show before dinner.

But there was another consideration, too. The Rocky Horror Show was written and designed with an extremely specific type of venue in mind—one that could, in essence, be reimagined, and redesigned, as an old-time movie theater. The Royal Court Upstairs had filled that purpose admirably. All O’Brien required of White now was that he locate them a similar home for the rest of the show’s run.

The Gaumont Cinema in Notting Hill was considered for a time. That was where the cast had gone to see the Russ Meyer movie, so there was a certain, and delightful, serendipity there. But Notting Hill was even further from the bright lights than Chelsea, a truly run-down area that still bore the scars, emotionally and physically, of the race riots that disfigured it back in the late 1950s. Chelsea had its problems, but at least it still had a fashionable cachet.

Which is when, with perfect synchronicity, the production was offered space at the Classic Cinema, at number 148 on the King’s Road itself.

A gorgeous Edwardian building opened in 1913, and previously known as the Chelsea Picture Playhouse and the Electric Cinema, the Classic stood on the corner of Markham Street, as King’s Road petered down toward the ominously named World’s End. But its life as a cinema was over.

The property had already been earmarked for demolition. Soon, a new branch of Boots the Chemist would stand where Hollywood dreams had once unfolded, peddling the dreaded 4711 to the olfactorily deprived youth of London, SW10. That was how White got the venue so cheap, but even he could only hold the bulldozers back for so long. The Rocky Horror Show would call the Classic home for just a few months, until October 20. And then it would have to move once again.

In the meantime, it was perfect. It was also derelict, shabby, and absolutely filthy. Where better to continue demolishing the expectations of the age?

Rocky’s Cocky

The Rocky Horror Show’s final night at the Royal Court, on July 21, however, was not the triumph it could have been. Rather, it was canceled after Rayner Bourton discovered, following the previous evening’s show, that he had managed to get some glitter down the front of his silver briefs, at a time when glitter was still made from tiny pieces of glass.

A few shards then ventured into those places where a male really would prefer not to find sharp jagged fragments of any description, together with a number of lacerations and even the first signs of infection. He arrived at the theater on schedule, but clearly he was in far too much pain to perform.

Little Nell offered to take his place for the show, and some consideration was given to the suggestion—Nell could be cut from the action a lot more easily than Rocky, and hindsight does wonder, with so many other theatrical conventions already being shattered, why they didn’t just go with it. But no.

The announcement was made; the show was off. Meaning—among the sixty-three ticket holders—disappointment for Mick and Bianca Jagger, playwright Pam Gems and actor Elliott Gould.

Harriet Cruikshank was delegated to break the news to the VIPs that the night was not going to happen, and naturally they inquired why. Cruikshank explained that one of the cast had been taken ill.

Mick Jagger pressed for further details.

“Rocky’s got something the matter with his cock,” she replied.

To which Jagger is said to have responded, “Haven’t we all?”

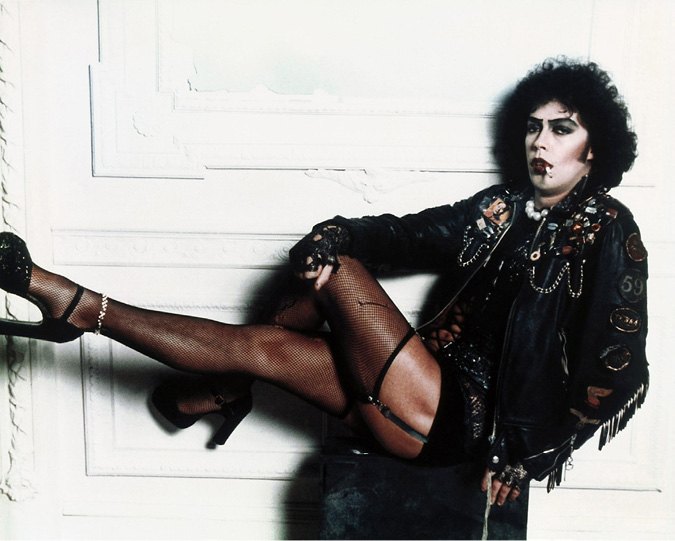

Come up and see me sometime: rank (Tim Curry) in sex kitten mode.

Twentieth Century Fox/Photofest

The Queens of King’s Road

Patricia Quinn confessed herself astonished by the success of The Rocky Horror Show; that they had the likes of Vincent Price and Mick Jagger lining up to see a minor musical in a sixty-three-seat theatre. Now they would have to catch it at a 270-seat cinema.

Scheduled to reopen at the Classic on August 19, The Rocky Horror Show was billed on the street with a poster that sought to remind passersby that it was a play, and not what the London magazine Time Out described as “one of the B-movies it so successfully sends up”; The Rocky Horror Show Alive On Stage.

With no downstairs theatre to take into consideration, the show’s nightly schedule now shifted to a more traditional eight performances per week, at 9:00 p.m., with two shows every Friday and Saturday at 8:00 and 10:00, but none on Sundays (to evade actors union Equity’s insistence that everyone be paid double time for working that day).

Midnight matinees, too, would filter into the itinerary, some to accommodate the cast of the other London shows who were desperate to catch The Rocky Horror Show (Lauren Bacall and Angela Lansbury were present at the first); another serving as a benefit for technician Roy Truman, who lost an eye and was left partially deaf after one of the show’s explosive effects detonated prematurely.

Still the cast’s pay soared generously, from £18 a week at the Royal Court, to the West End standard £60 a week. Yearlong contracts, too, were proffered, to be signed by all except Bourton, who was heading back to Scotland for his return engagement at the Citizen’s Theatre in Glasgow; and Covington, contracted as she was to open as a handmaiden in Tony Richardson’s Antony and Cleopatra at the South Bank.

And that was the sole reason she left, although rumors—which naturally have become fact on the Internet—continue to insist that she was forced to depart following an accident, a blow to the head sustained when Rocky accidentally cracked her head against a concrete pillar during their dance routine. That incident did happen, leaving Covington with a massive bruise on the right side of her face. However, she made a full recovery (she even performed the following evening), and she saw out both her initially contracted three weeks and the additional two-week extension before those other commitments called her away.

Hindsight suggests it was not a particularly well-starred move. Anthony and Cleopatra was being staged in an honest-to-goodness tent, and one night—the very night that Patricia Quinn went to see the performance—the tent blew down. “It was a ghastly, dreadful, dreadful production,” Quinn told Rayner Bourton. “Julie made a mistake leaving our show.”

Covington’s departure, just days before the cast was due to record the soundtrack LP, allowed her replacement as Janet, O’Brien’s old friend Belinda Sinclair, to appear on disc in her stead. And with his traditional knack for getting things done, King was able to have the first pressings of the LP on hand and ready to be sold in time for opening night at the Classic.

Janet II—Belinda Sinclair

Belinda Sinclair first came to public attention when she played Julie Farthing in three early episodes of Bright’s Boffins, a BBC sitcom about a group of eccentric scientists working for the government. Scarcely remembered today, it was a wonderful romp that featured Alexander Doré (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang) as the titular Bertram Bright, and though Sinclair’s role was comparatively tiny, she made a grand impression on viewers.

A decade later, she reappeared on the small screen as Fran, the long-suffering girlfriend to Hywel Bennett’s insufferable Shelley in the sitcom of the same name, and an entire generation of male viewers fell head over heels in love with her.

And in between times, she appeared in Hair, where she first met O’Brien and company, before not only replacing Covington in the nightly performances of The Rocky Horror Show, but also beating out Elaine Page in the process.

It was time to begin rehearsals, first at the Phoenix Theatre on Charing Cross Road and then at the Classic itself, time in which the cast would familiarize themselves not only with their new costar but also with the larger stage on which they could now operate.

The play had been lengthened, too, to better meet the expectations of a more conventional theatrical production. Two new songs were added to the running order: “The Charles Atlas Song” (later retitled “I Can Make You a Man”) and its reprise, and “Eddie’s Teddy,” while Bourton adopted a new American accent to replace the midlands brogue he had hitherto been utilizing. All these things needed getting used to.

The existing stage set remained in operation, but the tattered curtain that was draped across the stage was now the property of the ACME Demolition Company. The ramp that led to the back of the room had been widened and topped off with a rainbow that would light up during the final number, “Superheroes”; and when Riff-Raff gazes down on the approaching Brad and Janet, he now mounted a black-painted ladder and peered through a light box, fifteen feet above the crowd, his face lit by ghoulish green gel.

There was even a new souvenir program, replacing O’Brien’s original cartoon drawing with a professionally designed piece from artist Michael English.

The wardrobe budget was increased, and Blane gleefully spent it. Understudies were introduced, Angela Bruce and Trevor “Ziggy” Byfield, another veteran of Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar, and while there were real ushers and usherettes to handle the patrons, the show’s original spooky ones (their numbers swollen by Byfield and Bruce) remained on hand to thrill, shock and in some cases terrify their charges. According to one especially pernicious legend, sensitive singer-songwriter Cat Stevens was so unnerved by his ghoulish escort that he fled the Classic before he even reached his seat, and others, too, succumbed to a similar shock. Tom Woodger of the band Blue Giant Zeta Puppies recalls his initial exposure to the show’s unconventional, but so literal, floor show.

The venue was small, and seemed a little dingy. As the time for the performance approached, the doors from the bar into the auditorium opened with nothing in the way of announcement, almost as if they might have been opened by mistake. People began to drift in and look for seats. I was rather surprised to see that the walls seemed to be surrounded by scaffolding and swathed in dust sheets. The whole place seemed very quiet, and more than a little tense. The audience were filing in a little uncertainly, speaking in whispers. A large screen, almost like a cinema screen, hid the stage, and had “closed for refurbishment” roughly hand painted across it. The whole place looked deserted and derelict. . . .

I was well down the aisle before I noticed the store dummies. They were arranged among the scaffolding around the sides of the auditorium, dressed in operating theatre gowns and masks. When I caught one of them moving out of the corner of my eye, I was sure I had been mistaken. I was still staring hard at it (it seemed to be dressed in stockings and high heels under its gown . . . which struck me as slightly unusual, as it appeared to be male), when another theatergoer screamed loudly.

The whole crowd, me included, jumped about a foot in the air. It seemed I wasn’t the only one who had seen a dummy move. A second after the scream, the whole placed dissolved into laughter. . . . The cast, straight faced and silent, emerged from the scaffolding and strode through the crowd to their places, and we all took our seats. Still chuckling . . . Nervously. . . .

Still, a 270-seat cinema was a lot of ground for the ghouls to have to cover, so somebody hit on the idea of recruiting some showroom dummies as well, to stand around in uniform, indistinguishable in the gloom from the real helpers.

It all added to the atmosphere.

Cat Stevens must have been one of the few stars of the day who didn’t see Rocky Horror. Throughout its run at the Classic, the play received visits from David Bowie and his then wife Angela (who apparently irritated the entire cast by incessantly “ooh-ing” and “aah-ing” throughout the show), as well as drummer Keith Moon, preparing for his later devotion to The Rocky Horror Show’s Los Angeles incarnation.

Sam Shepard came along and “surprised himself by liking the show,” says Jim Sharman; as did fashion designer Ossie Clark; playwright Andrew Lloyd Webber; Hair author James Rado; actress, singer and Dali associate Amanda Lear.

Marianne Faithfull dropped by, curious, perhaps, to discover what she had missed out on; along with singer and actor Murray Head, whose younger brother Anthony would later become Frank in his own right; and, on one memorable evening, the man without whom such a show might never have existed. Sixty-two-year-old American playwright Tennessee Williams, whose Cat on a Hot Tin Roof had truly kick-started British theater’s drive to escape the censorial Lord Chamberlain, surely could not have been prepared to witness all that he had wrought. But maybe he was. Apparently, he laughed and applauded as much as anybody.

“The Classic was perfect for Rocky,” says another audience member, Gary Weightman. Still a schoolboy, he wandered in out of pure curiosity, drawn by the poster on the street and the mentions in the press. A big glam fan, he was “convinced I was that it was something I needed to see. But I also knew, or suspected, that it was something that I maybe didn’t want to see—at thirteen, your feelings about sex and sexuality are still very much up in the air, and Rocky Horror was pure sex, that much was obvious, and probably very twisted sex.”

And when it was over, “I came out of the theater and the whole world looked different to me. It looked drab, colorless, and gray. I felt that I’d just spent an hour and a half literally being transported into a whole new way of living and thinking, a universe in which anything was possible but, more than that, anything was probable. You just had to open your mind and look for it.”

One more satisfied customer.

But not everything went according to plan. That year marked the beginning of the first terror campaign ever waged in London by the Irish Republican Army—a pair of car bombs detonating in March, included one outside the Old Bailey law courts; more at underground and mainline railroad stations in the center of the city. All of London was on edge, which meant that even the suspicion of a warning could cause any amount of chaos. Most of the West End’s theaters received at least one threat as summer 1973 turned to fall. It was a sign of The Rocky Horror Show’s popularity that it received three!

A Permanent Home

Just as the Classic was only ever intended to be a temporary home, so Rayner Bourton was now only intended to be a temporary Rocky. At the end of September, he bade farewell to The Rocky Horror Show and returned to Glasgow, for a season that included Happy End, The Devils, The Taming of the Shrew and MacBeth. Back in London, he would be replaced first, but only briefly, by Andy Bradford (destined to become one of Britain’s most in-demand stuntmen), and then by Ben Bazel, as the show prepared to relocate to its third home in four months.

This time, however, the switch would have some permanence. The necessary performance license did not arrive in time for the show to make its scheduled reopening on October 29, but on November 3, The Rocky Horror Show reopened at the 350-seat King’s Road Theatre, where it was to play continuously for close to the next six years.

Opened in 1910 to house both movies and roller skating, the rather gloriously named Palaseum Rink and Picture Palace converted to movies just one year later and underwent a succession of name changes over the next half a century.

It was the King’s for a while, the Ritz, the Essoldo and—a little confusingly if you weren’t speaking precisely—the Classic Curzon, as opposed to the Classic alone, farther down the King’s Road.

Its life as a cinema ended in 1973, and it was repurposed as a theater just in time for The Rocky Horror Show. The two would then march hand in hand together for the remainder of the decade, but they were not alone in luring the weird, wild and woolly of the world to World’s End.

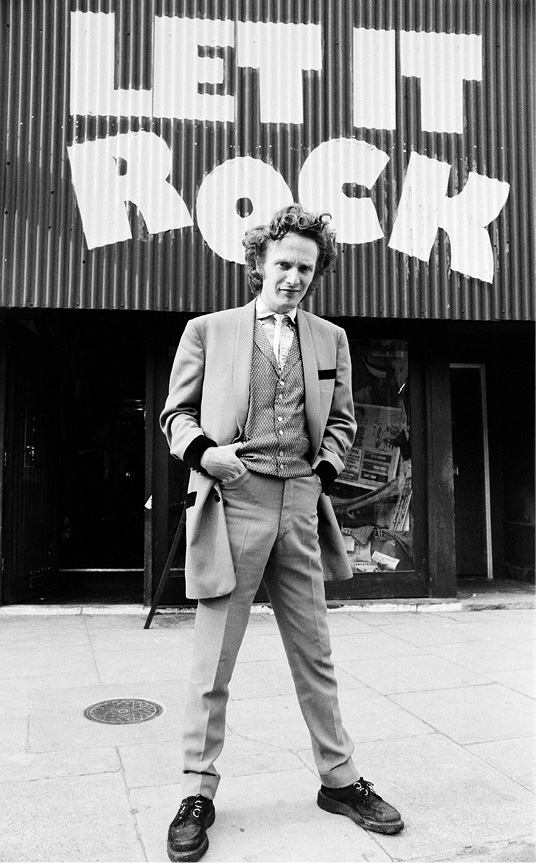

Not quite, but more or less, across the street, that old Teddy Boy boutique Let It Rock had now morphed (under the same ownership) into Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die. A few months later, it would change its name again, to Sex, and swagger into infamy as the boutique from within whose walls haberdasher Malcolm McLaren and fashionista Vivienne Westwood would claim to have blueprinted punk rock.

And how appropriate it is that a cultural movement that prided itself on its absorption of kink, deviance and anti-sociability should be birthed in the shadow of a play that likewise celebrated all three.

“I think certain elements of punk—for instance, ripped fishnet tights and glitter and the funny colored hair—a lot of those aspects of it were directly attributed to Rocky,” Sue Blane told authors Scott Michaels and David Evans, and she is correct. For viewers in at the birth of the Rocky Horror participation boom, the burgeoning punk rock fashions were little more than an egalitarian adaptation of the kind of items that the Rocky crowd had been wearing for a while. Indeed, many of them were sourced from similar places.

Jen Worthington, eighteen years old and devoted to the stage show, recalls following in Sue Blane’s old footsteps and scouring junk shops in London’s grimmest corners, second-hand clothing stores and East End market stalls in search of a Magenta-style outfit, to be worn both to the theater and to punk shows, “and I quickly realized that a lot of other kids were doing the same thing.”

With the Sex boutique representing his own vested interest in dressing the fashion-conscious punks of the era, McLaren later insisted, “I never gave Rocky Horror a second thought . . . I don’t think I was even aware of it.”

But Richard O’Brien is not alone among those who remember him attending the show on several occasions. For the Walk on the Wild Side documentary, O’Brien recalled “[McLaren] used to come along . . . to see how it was done. Little Nell, for instance, with her brightly colored socks and tap shoes with glitter on, and fishnets and striped shorts. That look is pre-punk.”

McLaren’s apparent disregard did much to squeeze The Rocky Horror Show’s omnipresence out of every halfway definitive history of British punk culture.

That does not mean it was not a part of it, however; and it does not mean that the kids who made their way for the first time into McLaren’s little shop did not do so without at least a little prompting, just up the road, Frank, Magenta and Riff-Raff—all of whom were themselves regular visitors to McLaren’s store, under all of its titles, during their time on the King’s Road. Indeed, Magenta’s shoes and space boots were both purchased from that unprepossessing little boutique.

Just down the road from Rocky’s second home, Malcolm McLaren’s Let It Rock spearheaded the glam generation’s retro-fifties dreams—and furnished some of the Rocky costumes, too.

© Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy Stock Photo

A Disreputable Child of Its Disturbing Times

Even before punk, however, The Rocky Horror Show was unquestionably a child of its times, and its times embraced it wholeheartedly. Mick Ronson, David Bowie’s peroxide- and glitter-soaked guitarist, admitted that the first time he saw The Rocky Horror Show, he wondered why anybody else even attempted to play glam rock any longer, because they were never going to top what O’Brien and Co. had created.

Another glam icon, the late Brian Connolly of the Sweet, described it as “the Spinal Tap of the 1970s. Rocky Horror took everything that was going on in glam rock, the drag, the fifties, the science fiction, and took them to ridiculous extremes.”

But whereas a future generation of artists would complain that Spinal Tap, that so-hilarious cinematic parody of the Heavy Metal lifestyle, was just too close to the truth to ever be construed as amusing, Connolly admitted that he loved Rocky Horror—“and if I’d had the nerve, I’d have played Frank-N-Furter myself.”

He was not alone in nurturing such an ambition. Indeed, fellow glam icon Gary Glitter went one step further and actually took on the role in earnest, touring New Zealand alongside Rayner Bourton with a production of The Rocky Horror Show in 1977. And Connolly’s bandmate Mick Tucker once acknowledged that, while glam rock flirted with a wealth of unconventions and oddities, “The Rocky Horror Show took them home and fucked their brains out.”

Yes, The Rocky Horror Show was brazen; yes, it could be construed as crude. Contrary to Rayner Bourton’s fears, nobody was arrested; no one was hurt; no one was scarred. The effect it would have on impressionable minds, however, remained profound.

Andrew John Mitchell, director today of some half-dozen mid-Atlantic productions of The Rocky Horror Show, dating back to 2002, recalls, “I have been in love with Rocky Horror since . . . I think I saw it the first time when I was sixteen. My father used to live down in Virginia Beach and there was a theater next door to the restaurant he managed. I was like ‘ooh, look at this cool theater,’ so I would go with him on a Saturday night and I would see the show.”

His résumé alone speaks to the impact it had on him.

Singer TV Smith, whose punk band, the Adverts, scored a 1977 hit single with “Gary Gilmore’s Eyes,” was another of the teens lured in to The Rocky Horror Show by its escalating word of mouth, sometime during its first year. “I travelled up to London to see it in that theatre in Chelsea. Was quite an eye-opener for a teenager from Devon. . . .”

Actress Linda Davidson, famed through the mid-late 1980s for her role as single mother Mary Smith in the then-newly launched television soap EastEnders, recalled abandoning a late 1970s school trip to the musical Grease and joining the Rocky Horror audience instead. While the rest of her friends were off playing Danny and Sandy, for the next four years “I was Columbia”; and a decade later, she would be Columbia again, on the West End stage.

Another early witness to the power of both the production and that particular character was seventeen-year-old Toyah Wilcox—future pop star and destined, too, to become one of Richard O’Brien’s costars in the movie Jubilee.

It was 1975 and, with her pink and black hair, “I thought I was alone in the world.” And then she saw a Picture Show movie still of Little Nell. “It was a picture that penetrated my DNA,” she wrote in Rocky Horror’s twenty-fifth-anniversary program. “My life changed at this point and I knew I wasn’t alone. The Rocky Horror Show dared a generation to be different.”