25

Deadpan Dolores and Other Tales

Meanwhile, back in the early 1980s . . . .

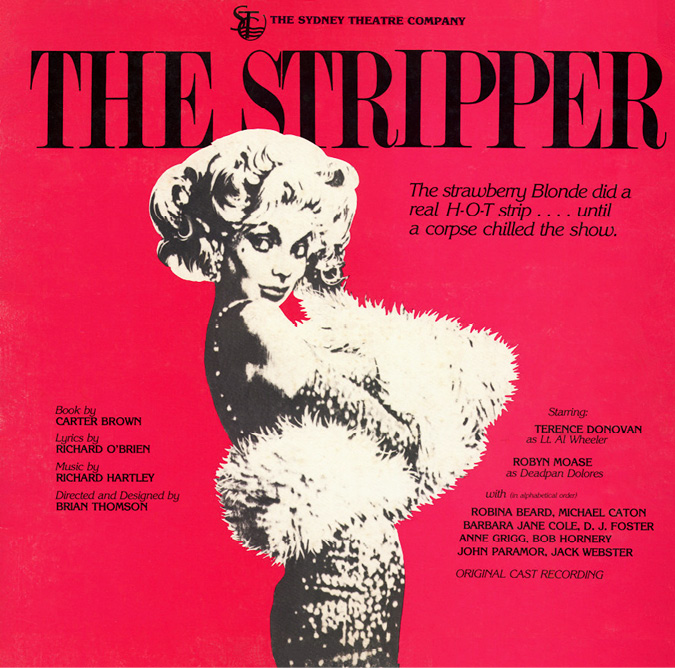

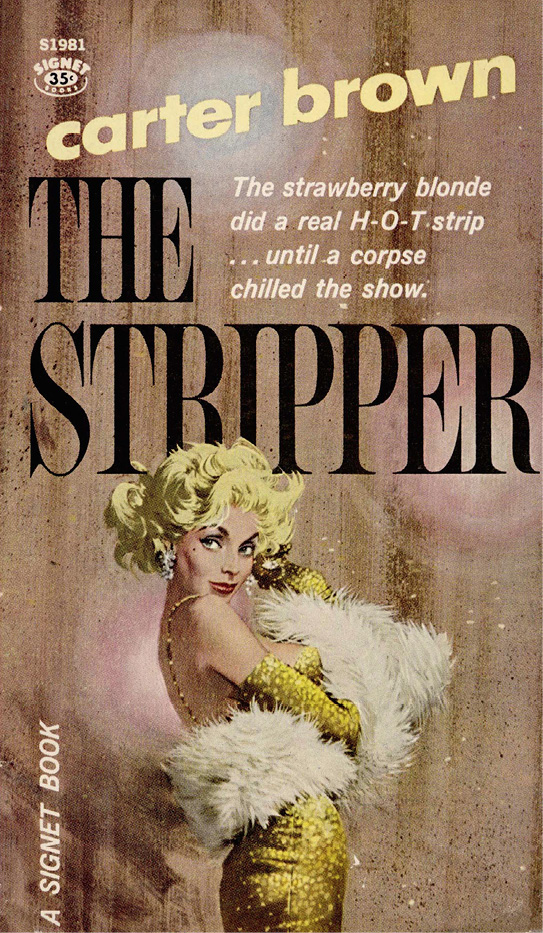

Shrugging off the twin blows meted out by a cruel 1981, Richard O’Brien’s next creation was The Stripper, a musical adaptation of the Carter Brown novel of the same name. Published in 1961, a couple of years before O’Brien left New Zealand, The Stripper is another of Brown’s most deathless classics. And how could it not be, with its so matter-of-fact front cover, and a teaser for the ages: “The strawberry blonde did a real HOT strip . . . until a corpse chilled the show.”

It is one of a series of novels that revolved around the casework of Pine City homicide cop Lt. Al Wheeler, and the story opens with a heart-stopping tragedy. A young woman, Patty Keller, apparently about to commit suicide, is finally talked to safety from the fifteenth-floor ledge where she has been teetering for hours. Wheeler reaches out for her hand, when suddenly Patty’s entire body contorts with pain, and she falls to her death.

Enter the stripper. The dead girl’s cousin is Deadpan Dolores, so named because she performs her act without permitting her face to show a single emotion. She points Wheeler toward a dating agency that Patty had recently signed up with; its proprietors in turn inform him that she’d had just one date, with a florist named Harvey Stern. Who, Wheeler is somewhat surprised to discover, is also a regular at Dolores’s strip club.

Another death, further intrigue, The Stripper is a classic pulp whodunit, and O’Brien’s adaptation was as taut as the original novel—with the added bonus of seventeen new songs, styled for an old-time Hollywood gangster flick, and all penned by O’Brien and Richard Hartley.

The idea for adapting a Carter Brown tale came, O’Brien later said, from a meeting with the author’s daughter. Interviewed for Milton Keynes Theatre, he recalled, “As soon as she told me who she was I thought ‘Ah ha!’ and could immediately see some mileage in the idea of adapting one of his books.”

His original notion, hatched with Richard Hartley, was to write some rock ’n’ roll. “But when I started to think about it I realised these characters were more likely to listen to Ella Fitzgerald and Sinatra.” So that became the play’s direction, a slice of moody film noir, replayed on a spartan stage.

The US paperback printing of Carter Brown’s The Stripper.

Author’s collection.

With the Sydney Theatre Company handling production and Brian Thomson recalled as director, a great cast came together—Terence Donovan as Wheeler, Robyn Moase as Dolores, Anne Grigg as Patty Keller.

O’Brien himself would not appear in the play, but of course his imprimatur is all over it, in the sly humor of the songs, the fast pace of the action, and—as affectionate as Rocky’s tribute to the old-time B-movies was—his unmistakable love for old-time pulp and classic musicals.

Arguably, none of the songs come close to the stand-alone majesty of the best of The Rocky Horror Show or Disaster (a failing to which most of O’Brien’s subsequent musicals have been prey), but all work within the context of the show, and all are certainly strong enough to keep the action moving along.

Unfortunately, director Thomson did not agree. He felt the script was overlong; that it needed condensing, simplifying and reediting. Rehearsals stumbled as the cast tripped over problematic dialogue, and Thomson begged O’Brien to allow him to try and fix the difficulties.

O’Brien refused, and the resultant argument ended with Thomson effectively barring him from the theater.

Despite this, O’Brien still regards The Stripper as one of his finest pieces of work, even shading The Rocky Horror Show in his estimation at times, and it remains one of the tragedies of modern theater that it is so underappreciated, underestimated and largely unseen.

Thankfully, we do have the soundtrack album.

Top People Hit the Bottom

Back in the UK, O’Brien’s next project was to reunite with Hartley to write three songs for the upcoming Alan Arkin movie The Return of Captain Invincible (1983). He was, however, merely marking time, awaiting the moment when he could unleash his next vision on the world.

Top People, he later told the Guardian newspaper, was a revival of a comedy he first wrote “in the early 60s,” concerning what turns out to be an especially inept plot to assassinate a Latin American director.

With O’Brien joined in the cast by Peter Blythe, Jane How, Donald Churchill, Ann Way, Dawn Ellis, Andrew Robertson and Dilys Laye, Top People opened at the Ambassador’s Theatre in London—and closed just three days later, utterly crucified by critics who, O’Brien subsequently learned, “later admitted none of them had seen it. [But] they were very sneery about it on TV.”

Indeed, complaints that the play was both vulgar and incoherent were possibly borne out by the show itself, and while Top People is frequently referenced as a milestone in truly bad theater—a B-movie for people who don’t go to the movies—it also rates as a true career low for O’Brien.

“The battering I took over that made me feel that I didn’t want to put myself up for that,” he told writer Phil South the following year. “I’m not a masochist. I didn’t get into this business to be hurt by people that I have no respect for, or have very little respect for, because they’re lazy. So I went back to acting.”

True to his word, Top People effectively marked O’Brien’s retirement from the front line of British entertainment for the remainder of the decade. He even abandoned plans for a new musical, this time concerning two homosexual vicars who receive a visit from the Devil, and wittily titled Oh No, Not Faust Again.

The story was revamped as a prospective novella, unpublished but later unearthed by producer Michael White for auction in December 2010. But the musical was gone for good. “Because of the reception of Top People,” O’Brien continued, “I decided obviously I didn’t have a talent for writing for the theater. I was obviously inept, so . . . there was no point in me doing it any more.”

He had a small part in 1985’s Revolution, a true stinker of an historical epic starring Al Pacino, Donald Sutherland and Nastassja Kinski; he would pop up as a deranged sorcerer named Gulnar in television’s Robin of Sherwood rewriting of the Robin Hood legend in 1986; and he at least partially reprised Riff-Raff in Rolling Stone Bill Wyman’s Digital Dreams movie.

But it would otherwise be 1990 before O’Brien truly resurfaced, first at the helm of the newly formed Rocky Horror Productions company, and then as the acerbic harmonica-playing host of the television game show The Crystal Maze.

Long before the likes of Ann Robinson, Simon Cowell and Donald Trump made it de rigueur for television game show personalities to put down their contestants, O’Brien not only pointed out the direction they would take, he also did it with considerably more grace and style than any of his successors ever mustered.

O’Brien remained with the show for four seasons, departing in 1993 to be replaced by what you might describe as one of his own creations, former punk singer Edward Tudor Pole, who had most recently been appearing as Brad Majors in the London revival of The Rocky Horror Show.

O’Brien returned now to theater. In 1995 he launched his one-man revue Disgracefully Yours, finally crystallizing an ambition he’d held for at least a decade, to join Tim Curry in the realm of actors who have portrayed the Devil. And, like Curry, he was magnificent. He adopted the demonic persona of Mephistopheles Smith and with such success that the show has now become a stage musical in its own right, usually retitled for Mephistopheles himself.

Sticking with the sinister, he became the Child Catcher in the newly devised London production of Ian Fleming’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang; and in 2006 he reprised that same role during Queen Elizabeth II’s eightieth birthday celebrations at Buckingham Palace. He made a handful more movie appearances, and became a generous patron of the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital.

Indeed, O’Brien has, in every sense of that so wearingly overused phrase, become one of British entertainment’s most revered national treasures, and at every turn, The Rocky Horror Show looks over his shoulder—as well it ought to.

Far beyond his helming of the production company that now controls the rights to the stage show (but not, sadly, the movie), Rocky and O’Brien are joined at the hip. Even the annual fund-raisers that he ran for the Royal Manchester during the early 2000s were known as the Transfandango, to which he gathered “Dearhearts and Trans ’n’ Gentle People” to raise money for the hospital.

He has been honored in the city of Hamilton, New Zealand, with a statue of Riff-Raff perched proudly on the site of the old Embassy Cinema, where once he whiled away teenage afternoons, watching the B-movies that would inspire his greatest creation—although the tribute became laced with a great deal of irony in 2010, when O’Brien finally applied for New Zealand citizenship.

He was refused on the grounds of being too old—the country immigration laws had an age restriction, and, three years shy of his seventieth birthday, O’Brien fell outside of its parameters.

The authorities did eventually recant, in late 2011, but only after being held up for ridicule across the world, and most wryly by O’Brien himself.

They erected a statue of him, and celebrated him as one of New Zealand’s most beloved sons—and then told him he was too old to actually become one.