The end of The Rocky Horror Show’s London life in 1980 did not mark the end of, or even that much of a hiatus in, its British life span. There was a handful of regional repertory theatre productions, unofficial but enjoyable too, and there always seemed to be rumors flying that there was something Rocky-shaped just over the horizon . . . even if it did turn out to be Shock Treatment.

But then 1983 dawned, and, with it, one of The Rocky Horror Show’s most successful, most effervescent and—and this is the important part—most audience-friendly productions yet, courtesy of the Kenneth More Theatre, in the London suburb of Ilford.

More himself was not a party to the creation of the venue that bore his name. But he was a major part of the inspiration that created it. One of Britain’s greatest, and most beloved, character actors, it is all but impossible to trip through a list of the mid-twentieth century’s most fondly remembered homegrown movies and not find More’s name somewhere in the cast, from Reach for the Sky (playing a paraplegic air force fighter ace) to Genevieve (a gentle comedy set around the annual London to Brighton vintage car rally); from A Night to Remember (dramatizing the sinking of the Titanic) to Doctor in the House (hijinks in hospital).

Accomplished, too, in the theater; a veteran of the Windmill, where comedians were the intermission between the famous dancing girls; capable of swinging from Shakespeare to Chaplin at a moment’s notice, More was the consummate performer. Who better, in 1973, to name a newly opened theater for?

More accepted the honor, and on January 3, 1975, he was present for the venue’s opening. Now, a decade later, the Kenneth More Theatre (KMT) was renowned among the UK’s most adventurous venues and a magnet for amateur companies throughout the region.

An Unpromising Start

The decision to stage The Rocky Horror Show was originally an economic one, as much as anything else. Easter was a traditionally slow time in the local theater trade, and it was felt that by stepping out of the realm of the KMT’s usual fare, the drop-off in “regular” theatergoers might be offset by the show’s appeal to a more general crowd.

Plus, with only eight actors, five musicians, minimal set and low production costs, it could afford to fail, if that was to be its fate.

The shoestring nature of the presentation was further illustrated by the decision not to perform any matinee shows, and to avoid Good Friday altogether. Indeed, across The Rocky Horror Show’s two-week schedule, there would be just seven performances, with the first Saturday further encouraging a less-than-customary audience by being paired with a fancy-dress contest.

It was not a success. Despite the chosen Doctor Frank-N-Furter, Jeffrey Longmore, having already proven his worth in a production in Oldha a couple of years before; and the role of Columbia going to the theater’s own choreographer, Loraine Porter, audiences remained unconvinced.

Of two hundred or so attendees (less than two-thirds the venue’s capacity) that Saturday night, barely twenty bothered to dress for the occasion. Indeed, although director Vivyan Ellacott had certainly constructed a faithful, and thoroughly enjoyable, production, most nights were marked by at least a handful of people walking out on it. By the end of the run, it was clear that staging the show had actually left the KMT nursing a loss of around £500.

However, like the movie before it, sometimes it is not “what you do” but “who you know” that matters, and one evening brought theatrical producer John Farrow to the show.

He adored it; more than that, he was adamant that it should not perish once its run was over. And, while spreading the word among the network of agents, theater managers and bookers with whom he conducted his business, Farrow found himself talking Rocky Horror with Paul Barnard, the Australian producer charged with revitalizing what had once been the thriving Theatre Royal in Hanley, near the midlands city of Stoke-On-Trent.

Opened in 1852 in what had once been a Methodist Chapel before relocating to a new building on the site of an older theater, the Theatre Royal thrived for close to a century before fire destroyed the building. A new theater rose from the ashes, opening for action (with Annie Get Your Gun) in 1951, but, just a decade later, falling attendances and a general lack of public interest saw the doors closed to the arts, and the building was converted to a bingo hall.

Twenty years on, the bingo, too, was on the wane, and the building was put up for sale. It was purchased by a local trust headed by lawyer Charles Deacon; and, with Barnard installed to oversee its future, the Theatre Royal reopened with a Christmas 1982 pantomime production of Babes in the Wood.

It was a success, but finances were tight, and the theater still required a lot of renovation. The Theatre Royal Restoration Trust’s sensible solution was to seek out an affordable production that could be sent off on tour, with its proceeds being plowed back into the venue. Farrow convinced him that the Kenneth More Theatre’s production of The Rocky Horror Show might be the answer to his prayers.

The Horror Comes to Hanley

May 1984 saw the KMT production revived at the Theatre Royal itself, a rambunctious entertainment that fared considerably better here than it had in Ilford. Indeed, such was its success that a second showing was arranged for late September, and into October, while Barnard busied himself extending its reach even further.

The KMT already had experience with touring productions; back in 1978, the theater oversaw a six-month outing for a very successful revival of Hair.

The arrangement between the KMT and Barnard called for Vivyan Ellacott to retain his status as director, with full artistic control; Barnard and the Theatre Royal Hanley would then assume the financial and logistical management of the Kenneth More Theatre’s Production of The Rocky Horror Show—a long-winded title for what was destined to become one of the most startling success stories of mid-late 1980s British theater.

The production returned to Hanley in early November, the first halt on a short tour that took it first to nearby Birmingham and then up to Glasgow, and already audiences were getting into the spirit of the show.

Word of the American responses to showings of the movie had finally reached the UK—such details moved a lot slower in the days before the Internet came along, but word of mouth was no less pernicious. Fanzines and sci-fi mags all talked about the phenomenon; and a so-called Original Audience Par-Tic-I-Pation Album, recorded at one of the movie’s New York screenings, was available for anyone who really wanted to delve into the details.

Many of the show’s fans maybe did not know exactly what to say, and what to throw, as the story unfolded, but that was not necessarily a bad thing. It certainly added an extra dimension of spontaneity to the occasion.

Indeed, cast and musicians alike soon found themselves needing to take serious precautions to protect themselves from the hail of missiles that was being hurled in their direction by these so-enthusiastic audiences. In Glasgow, keyboard player Malcolm Sircom was struck by a coin; in Hanley, drummer Ken Newton took to wearing an old World War I-era German military helmet, complete with a spike rising out of its crown. Of course, Longmore could not resist incorporating the vision into the act, during the scene where he introduces Rocky to the family: “Magenta, Riff-Raff, Columbia, and Kaiser Bill in the Pit.”

Like Curry and Livermore before him, Longmore knew when to improvise. One of his most popular ad-libs, which itself became a tradition in the production, followed his introductory performance of “Sweet Transvestite.” With the audience howling its approval, an ovation that frequently lasted for minutes, the flow of the scripted dialog was completely shattered. So Longmore took to hamming it up, bowing to the crowd, encouraging their devotion, milking the applause. And then snapping “I haven’t finished yet.” It worked every time.

This initial outing was merely the preface, however. In February 1985, back in Glasgow, the Kenneth More Theatre’s Production of The Rocky Horror Show launched what would ultimately become a monstrous, thirty-nine-week British tour, not simply scouring the country, but allowing Rocky to refresh regions that he had never previously reached.

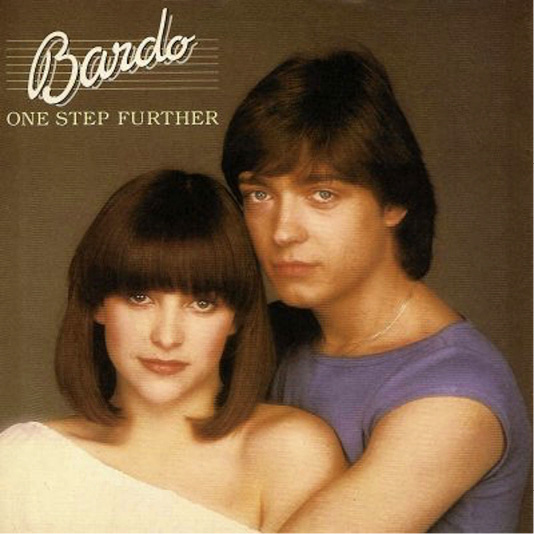

The nature of the tour—and the sheer demands it made on its cast, physical and in terms of time—ensured a fairly regular turnover of cast. The 1985 journey featured just two members of the original 1983 team, Jeffrey Longmore’s Doctor Frank-N-Furter and Jeff Pirie’s Doctor Scott and Eddie. But it welcomed its first national names, singers Sally Ann Triplett and Stephen Fischer, otherwise known as the pop duo Bardo.

Sally Ann Triplett and Stephen Fischer of the pop duo Bardo, stars of the 1985 Kenneth More Theatre production of Rocky.

Author’s collection

In 1982, the pair represented the United Kingdom in the annual Eurovision Song Contest (two years earlier, Triplett also performed there with the band Prima Donna); they finished seventh in the competition itself, but their entry, “One Step Further,” reached #2 on the British chart, and Bardo were still performing around Europe. They weren’t averse to breaking into excerpts from their best-known song during The Rocky Horror Show, either.

A new band, too, was in place. But the new cast was equal to the task—not only of executing the play every night, but also of ensuring that it went from success to success.

Barnard’s agreement with Richard O’Brien and the Samuel French Agency (the long-established theatrical publishers through whom all would-be Rocky producers must go) had guaranteed Hanley exclusive touring rights for the remainder of the year. But, however straightforward its itinerary appears when recalled by history, that first tour was scarcely a simple beast to arrange.

Many of the dates were only fixed once the tour was under way, and theater managers could see how well the show was doing at other venues, a state of affairs that created chaos when it came to offering contracts to the cast and crew (they eventually settled on renewable three-month ones), and even bedeviling the negotiations with O’Brien. What, after all, was the point of Barnard winning the rights for a long tour when it might all be over in a month?

In any event, all such fears regarding the show’s bankability proved groundless. Not only could The Rocky Horror Show have filled its datebook almost twice over, many venues demanded return visits from the show, beguiled not only by the strength of the show, but by the versatility of the cast as well.

In Leeds, for instance, the cast found itself playing on one of the smallest stages any of them had ever seen . . . so tiny that Barry McKenna, as Doctor Scott, could not even operate his wheelchair. So he simply stood up, pushed it to one side and declared, “It’s a miracle! I can walk.”

There were not many other plays that could survive a game-changing moment like that!

Where versatility could not fill the void, improvisation stepped in. One evening, Judith Eyre, playing Magenta, was unable to perform, and her understudy, too, was indisposed. The show went ahead without a Magenta, but with Doctor Frank-N-Furter, David Dale, filling in as the Usherette.

On another occasion, in Southsea, it was Dale who was absent.

No problem; they’d just send on his understudy, Stephen Fischer, who normally played Brad. Unfortunately, however, he did not have an understudy. A frantic call brought his predecessor in the role, Christopher Marlowe, hurtling eighty miles down from London to fill the breach.

Perhaps the story that most chroniclers of the KMT production love best, however, retells the night that Julia Howson, Janet on the 1987 tour, inadvertently went onstage without her underwear—an omission she only discovered when Magenta and Riff-Raff began divesting her of her clothing.

Moments such as this—the triumphs pulled out of imminent disaster—not only impressed theater managers; they thrilled the audience, too, and kept them coming back for more. By the end of the year, only impresario Bill Kenright’s revival of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat had outperformed The Rocky Horror Show on the theatrical touring circuit, and that had a newly recorded full-cast album behind it. The KMT production made it on the strength of word of mouth alone.

However, that was about to change as plans for the 1986 touring schedule began to coalesce.

Bobby Crush with Lasers!

Hitherto, the KMT vision of The Rocky Horror Show had scarcely changed since its Easter debut in 1983. Now, however, its renown was such that it was playing theaters that positively dwarfed the Kenneth More, in front of audiences that were accustomed to seeing grand sets, big budget effects, and even the occasional star name.

With a new agreement drawn up with Richard O’Brien (the author was granted a generous ten percent of takings), and bookings coming in at a faster rate than ever before, a whole new set, as elaborate as any seen in the West End, was devised and, with it, a spectacular array of lasers—at that time still regarded among the crème de la crème of theatrical effects.

The script and direction, naturally fluid in every fresh production, were revisited to take into account the larger crowds; and because a big show demands a big star, Hanley went out and got one.

Enter Bobby Crush, born just a short hop from the Kenneth More Theatre, in Leyton, East London, and since his late teens, in 1972, indisputably the British housewife’s number one piano-playing heartthrob.

Just eighteen, the prodigal pianist racked up a record-breaking half-dozen victories on Opportunity Knocks, the era’s equivalent to America’s Got Talent, The X Factor and all, albeit with more of an eye for light entertainment and variety.

Fresh-faced, and resplendent in frilly shirts and tailored tails, and with his repertoire of ever-so-slightly popped-up classics, Crush wowed the watching (and voting) public week after week, winning himself not only a record contract, but three headlining seasons at the London Palladium, too.

He performed with guest stars the caliber of Julie Andrews, Jack Jones, Harry Secombe and Max Bygraves, and hosted his own television series, Sounds Like Music. He scored hit records and played sell-out tours, and if comparisons with the great Liberace were inevitable, Crush only welcomed them—he had, after all, modeled his act on the flamboyant American showman.

Years later (in 2004), in fact, he even appeared as his hero in London’s West End, in the comedy Liberace’s Suit—celebrating not an item of clothing but a libel suit that the American brought against Britain’s Daily Mirror newspaper, in which he was described (deep breath) as “a winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavoured, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love.”

Apparently, Liberace thought it made him sound like a homosexual.

Later still, Crush would again take the role in the musical Liberace, Live from Heaven. Before any of that, however, Crush made his theatrical debut in a very different kind of role, as perhaps the most unexpected Doctor Frank-N-Furter yet. And he played it to perfection, joking both with the part and with his own, somewhat squeaky-clean image; raising the onstage temperature nightly.

How high? Too high, at least according to Richard O’Brien. Asked, by Time Out magazine, for his opinion of the now riotously successful Hanley operation, O’Brien complained of its vulgarity and condemned it as “amateur . . . the entire cast doing nothing but commenting on the action and looking up each other’s frocks and touching each other up. There’s no excitement. No danger.”

The cast would have disagreed, on the latter point, at least. There was plenty of danger, including that memorable evening in Wolverhampton when the customary shower of water pistols was suddenly dwarfed by a group of fans pulling one of the venue’s firehoses off the wall, and blasting audience and performers alike. With microphones sparking and equipment fizzing, the cast left the stage just as the power cut out altogether. The show was abandoned.

Another performance, this time in Stoke in November 1985, suffered a major second-half delay after the stage was bombarded with what the local Sentinel newspaper described as “water bombs, eggs, lumps of candle wax and metal spiked objects.” And when, one evening in late 1987, the stage became thick with clouds of flour, thrown by a particularly boisterous bunch of fans, Mark Turnbull, the current Doctor Frank-N-Furter, simply walked offstage.

Hanley had always adhered to the Chelsea show’s tradition of sending ghouls out into the audience, to get a little preshow entertainment going. Now the ghouls had something new included in their job description: sweeping all the debris off the stage during the interval.

But it wasn’t all carnage and chaos. Writer Peter Tatlow certainly felt the production kept firmly to the spirit in which it was intended. Reviewing The Rocky Horror Show’s stint at the Wimbledon Theatre at the beginning of April 1986, he raved, “great theatre, pulsating and exciting . . . a unique experience full of broad-minded goodnatured fun. The enthusiastic audience physically rocked the structure of the dress circle. You would not have heard a Sherman tank drop.”

The lasers were “phenomenal,” the production “stupendous” and Bobby Crush made “the cutest Transylvanian transvestite.”

O’Brien, on the other hand, loathed the lasers, and later, when he was informed that the production had been offered a berth in London’s West End, he refused to even consider the notion. His contract with the Theatre Royal had only ever been for performances in the provinces, out in “the sticks,” as London theater folk call any place that isn’t the heart of the capital.

The production had already played in and around London—suburban theaters in Catford, Wimbledon and Richmond; and closer in, too, with a couple of engagements at the Town and Country Club in Kentish Town, a venue that was no further removed from the West End itself than The Rocky Horror Show’s various roosts in Chelsea. But they weren’t the West End, any more than off Broadway is Broadway.

It is not a geographical state, after all; it is a spiritual one, and O’Brien was adamant. If The Rocky Horror Show was going to return to the West End, it would be under O’Brien’s direct aegis or not at all. Indeed, he was already hard at work raising the necessary funding to mount his own production of The Rocky Horror Show in London; Michael White had allowed his own production deal to lapse in 1984, and now O’Brien was preparing to take control in his own right.

Meanwhile, the KMT outing rolled on, and not only in the United Kingdom. July 1987 saw the production head overseas to Israel, to play two weeks at the Tel Aviv Cinerama before moving up to Haifa, and even a night in an open-air theater alongside the Sea of Galilee.

The Israeli adventure consumed four weeks . . . but only four weeks. One of the conditions of the production’s deal with O’Brien was that the show would never permit more than four weeks to elapse between engagements, all of which had to be in the UK. No matter how successful the Israeli visit was (and it was), and no matter how desperately the hosts wanted the show to remain longer, there just was no way of doing so. Not without putting the remainder of the production’s itinerary at risk.

The Beginning of the End

It was not, however, Richard O’Brien’s wrath that the production needed to be wary of. The Theatre Royal had recently invested in another production, a West End revival of Cabaret starring ballet dancer Wayne Sleep. But financial problems were suddenly rearing their head, a tempest of claims and counterclaims that pulled the tax authorities in as well.

The Rocky Horror Show could not help but be affected. A planned second foreign sojourn, this time to Spain, was canceled at the last minute, and with Paul Barnard being eased out of office, a new manager was installed to oversee the day-to-day running of the 1988 British tour, the chairman of the Hanley Board, Charles Deacon.

He did not only want to handle the logistics, however. Deacon also took on the role of producer, with all the artistic privileges that that implies.

Out went Rocky’s traditional birthing tank, and in came an egg.

Out went the once staid and respectable demeanor of the Narrator, to be replaced by a painted, grinning master of ceremonies, not so far removed from a performance of Cabaret.

Out went the mute beauty of the statues and objets d’art that had hitherto decorated the mansion, and in came a Venus de Milo, the object for a stream of newly scripted sexual jokes.

Out went the show’s traditional self-sufficiency, and in came a running joke about an offstage cat.

It was all most peculiar, but matters worsened. Deacon began making casting decisions, too, much to Vivyan Ellacott’s fury and, back in Ilford, the Kenneth More Theatre’s growing consternation. By the time the news broke that Richard O’Brien had finally confirmed a West End berth for his own The Rocky Horror Show, it was clear that the end was nigh.

Standard in almost all West End contracts, after all, is what is called a “barring clause,” prohibiting rival versions of a production appearing anywhere within fifty miles of London. The KMT production was effectively outlawed from many of the venues it was booked into, and with no time remaining in which to find replacement gigs further afield, the “four week” clause also came into play.

On August 6, 1988, the KMT/Hanley production of The Rocky Horror Show reluctantly, but triumphantly wound down with a week of parties and farewell performances.

An era had ended, and a phenomenon, too. Although it never played the West End; though it never made headlines; never even left behind an album or a professionally shot video, still this incarnation of The Rocky Horror Show could not be adjudged anything but a success, both financially (at least until the end) and culturally.

For years, after all, theater managers and stage producers had wrestled with the dilemma of how The Rocky Horror Show could ever accommodate those members of the audience, and a growing number of them at that, who wanted to treat the stage as a movie screen and behave as riotously in the theater as they did in the picture house.

Hanley had addressed that problem, and solved it. Fresh pauses were introduced into the script; fresh cues were given to tease the audience further. Audience participation wasn’t simply tolerated, it was invited—not in the contrived manner that so many post-Rocky productions have attempted to kindle such an atmosphere among their own onlookers, but in a way that played on the audience’s own desires and requirements, and allowed them full rein.

It was not an outright recipe for chaos; there would, for example, be no repeat of the night in Birmingham when a group of fans on the balcony decided to recreate the rainstorm for the people seated below them by emptying a bin-liner full of water over their heads.

But audiences were provided with a printed list of items that could be employed as the show proceeded, and most members of the cast had at least one trusted aside that might be delivered as the time for another deluge drew nigh. When Richard O’Brien complained that the lasers had transformed his play into “a rock concert,” with all the familiarity and frenzy that term implies, a lot of people asked why that should be a problem. The term “interactive” was still a decade or more from becoming the wearyingly familiar buzzword we know and cringe from today, but The Rocky Horror Show had already translated it into real life, into the world of theaters.

Now O’Brien was going to take it into the heart of the West End, as well.

Not only that, either. He was also planning lasers.

There is a sad, and somewhat tawdry, postscript to the Hanley saga. In 1989, Paul Barnard resurfaced with plans to take The Rocky Horror Show for a major European tour. Now the managing director of a new company, Panda Productions, based in Dusseldorf, Germany, he was working with KMT on what he claimed would be a return to the basics of their original production, shorn of all the gimmickry that its last few months, and its burgeoning popularity, had forced upon it, a true back-to-basics escapade, reuniting the original team.

Great things were promised, and initially, they were delivered. The artists’ touring contracts were the acting union Equity’s own; payments were made when and where necessary; and the equivalent of two weeks’ pay, pus air fares home, was deposited with the union to cover any worst-case scenarios. And on June 28, 1989, the show previewed to wild applause in the German city of Hanover, ahead of its official opening in Berlin.

But Berlin itself was a catastrophe, with an audience that responded not with the ovations that the production was accustomed to, but a round of booing and catcalls. Later, it transpired that The Rocky Horror Show was the unwitting victim of an organized protest—traditionally, the theater’s season was opened by one particular, favored, local company, and The Rocky Horror Show had preempted it. The jilted performers’ supporters responded in the only way they could, by showing their displeasure in the loudest manner possible.

At the time, however, the reaction was both a complete and a completely demoralizing surprise, particularly after the hostility was picked up by the local press, too. Furious arguments broke out with the German booking agent; the tour was effectively canceled on the spot, and Paul Barnard set about putting together a fresh itinerary on the fly.

Dates in Antwerp and Munich were hastily arranged, and went well. But others creaked beneath their last-minute arrangements; others still fell through for a variety of reasons. A tour that started out with such high hopes and ideals was rapidly falling apart. Finally, with morale at rock bottom, money running short, and the entire affair plagued by misfortune and disorganization, Barnard called a halt. The company returned home, and though he would make overtures to the KMT regarding a fresh tour in 1990, the Theatre said no.

After four years, one hundred seventy weeks and eighty-nine theaters around the UK, enough was enough.