29

A Twenty-First-Century Frank

It is not the most straightforward task in the world of theater, mounting a production of The Rocky Horror Show. But it is certainly one of the most rewarding, both in execution and, in terms of sheer entertainment, preparation.

Andrew John Mitchell explains. “When you go and you consider producing and directing and being involved with The Rocky Horror Show, there is a wealth of fantastic versions that you can find on YouTube.

“You can find so many things out there, resources to see what other people are doing. I remember there was . . . I think it was the 2010 UK tour that has this very blinged-out Magenta and a Riff-Raff with a full blonde wig, with these kind of points to his gloves, and they are all great ideas.”

In legal terms, an aspiring producer first needs to seek permission from the Samuel French agency; it is they who also collect the payments that will come due should the production take place. Unlike many productions, however, permission hinges not only on the nature of the proposed production, but also on its timing.

For perhaps obvious reasons, late October has established itself as the traditional time for local productions of the show, with the granting of the rights hinging on a variety of other factors—is there a major production taking place in a nearby city? Is there a touring edition heading into the same general area? Are there simply too many other productions already vying for attention in the vicinity?

All of those, of course, are issues that can be evaded with just a little attention to detail. A production staged in June is likely to face a lot less competition than one aimed at the heart of Halloween. Far harder to know is how one’s cast will respond once they are out on the stage and faced with an audience that might have been rehearsing for this night for movie-watching years beforehand.

Andrew John Mitchell recalls priming his cast for a 2010 production at the Chapel Street Theater in Newark, Delaware—a tiny offering, of course, when compared to the leviathans of Broadway, the West End and the like, but one that would be confronted with no less fanatical or demanding an audience. Rocky Horror fans get their kicks wherever they can, and with a local movie house that for years had been screening the Picture Show every Saturday midnight, the Newark crowd was as versed in Rocky etiquette as any other.

I used to be a member of a shadow cast, starting in 2001, so I had an awareness that I could bring to the cast about it, and I also knew people who I could bring in a week or two before the show opened, and say “alright, yell at them; don’t throw things at them, but yell at them” to get them ready for the interruptions.

Now, there are basic moments that people just know are coming, and that they can kind of mentally prepare for. But you never want to prepare too much, because it becomes unauthentic . . . to hold out too much for a line that (a) may not show up and (b) may be different to what you expected.

That happens a lot, because, from the audience’s point of view, it’s really easy to eventually learn the timing and the rhythm of a motion picture that does not change. It’s a different thing to then apply that to a musical, where the dialogue is not exactly verbatim. There is a difference to it, not a huge difference, but if you are looking for those certain words, and they don’t come . . . or, because it’s live theater, someone might miss a word, and then you’ve yelled out something that has nothing to do with what’s going on.

And so, slowly but surely, the two media began to merge with one another, the stage show taking more and more cues from the movie, precisely so the cast could predict what might be shouted or thrown at them, and so the audience wouldn’t be left foundering by a slut appearing where there ought to be an asshole.

Mitchell:

There is always the debate that I hear people say, especially theater people . . . there are some theater people that do Rocky Horror that don’t really get the audience participation. They are like “well, why is this here? I’m trying to do a show, I’m trying to focus, and there is this.”

[But my response is] as much as what we are doing on stage is important, that’s not why people came originally. [Beginning in the 1980s], most people weren’t coming to see Rocky because they wanted to just see the stage production. They’d heard what other people were doing and they were interested in what was happening in the audience, as much as what was happening on the stage.

But there is another reason why the audience participation is important.

Without it, Rocky Horror probably wouldn’t have survived.

Let’s Go to Bedella

The next major production, in 2006, was British, with the play now rejoicing under the newly revised (and legally binding) title of Richard O’Brien’s Rocky Horror Show. It was directed by Christopher Luscombe, a Royal Shakespeare Company alumnus who recalled, to the Daily Mirror in 2014, “The first job I did in the theatre was with [comedians] Terry Scott and June Whitfield.

“Then, I’ve played opposite Raquel Welch in the theatre and Meryl Streep, more recently, on film.” He directed former Cats star Elaine Paige’s live concerts “for several years”; worked with Harriet Harris—Hay Fever in Minneapolis—who was in Frasier and Desperate Housewives. And Judi Dench, of course.

“I’ve been slightly in awe of all of them, in a way, because anyone who works in the theatre is, in a sense, a fan.” He played Margaret Thatcher’s voice coach in The Iron Lady, and has worked extensively with Alan Bennett. With such a background, his version of The Rocky Horror Show was going to be remarkable even before it was staged; even before it was cast, in fact.

That cast became one of the finest to have emerged, at least in the UK, since the early 1990s. But the most attention went to Doctor Frank-N-Furter, as played by Chicago-born David Bedella.

He first came to attention with his portrayal of Satan in Jerry Springer—the Opera, a production that he helped shepherd from the Edinburgh Festival, where a half-empty first night suddenly exploded to standing-room-only for the second, and from there to the West End and beyond. He was rewarded with the 2004 Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical.

He starred in television’s medical drama Holby City; landed roles in the Hollywood blockbusters Alexander, Batman—The Intimidation Game and Red Light Runners; and when he stepped into the glam-rocking Hedwig and the Angry Inch, he confirmed his suitability for The Rocky Horror Show, long before he was considered for it.

In Bedella’s hands, Rocky Horror would march into its most glittering future yet; one in which yes, hints of Hedwig could be discerned, but welcomingly so. That stage show, after all, took its own musical lead from the very same era that spawned The Rocky Horror Show in the first place, and did so with sufficient panache that one does not instinctively cringe when critics describe it as one of Rocky’s closest living relatives.

Hedwig and Her Inch

Hedwig is an East German rock singer who, as a young man named Hansel, underwent gender reassignation in order that he might marry an American GI and thus escape his homeland’s Communist regime.

The scheme is successful, and soon, Hedwig finds herself living with her husband in Junction City, Kansas, only for him to walk out on her for another man. That same day, the couple’s first wedding anniversary, the Berlin Wall falls, effectively rendering all of Hedwig’s sexual sacrifices unnecessary.

Struggling to regain her equilibrium, and making ends meet by babysitting, Hedwig pairs up with Tommy Speck, the older brother of one of her clients, and together they form a band, the Angry Inch. Success is building, but then Tommy discovers the truth about Hedwig’s past. Disgusted, he walks out on her, taking many of the songs they cowrote with him. Tommy becomes a superstar; Hedwig and the Angry Inch find themselves back to playing bars.

There is a happy ending of sorts, Hedwig finding the strength to forgive both Tommy and herself, and a lot of great songs, too. It even became a reasonably enjoyable movie. But it was in its stage incarnation that the story truly excelled, with the role of Hedwig herself swiftly becoming as renowned as that of Doctor Frank-N-Furter, and for many of the same reasons.

Because it was a great drag act.

The play’s author, John Cameron Mitchell, was the first Hedwig when the play opened off Broadway at the Jane Street Theatre on Valentine’s Day, 1998. It ultimately ran for 857 performances, with subsequent Hedwigs including Donovan Leitch Jr (son of the 1960s singer-songwriter of the same name), Michael Cerveris and Ally Sheedy.

Cerveris also originated the role in the London West End in 2000; Bedella grasped it five years later as part of the Pride Festival 2005, staged in the submarine splendor of Heaven, a gay nightclub located beneath the railway arches under Charing Cross railroad station.

And now he was to play Hedwig’s spiritual godfather, a role into which he would not only inject a whole new sense of camp dramatics, but also a proud baritone that was at least as distinctive as any of its predecessors’ voices.

Not that he was keeping score on that count. Bedella told the BBC,

The most important thing was to push Tim Curry from my head, which was the hardest thing to do when somebody creates a role which has taken the world the way his has. We decided to make[Frank] American, which is a great choice by . . . Christopher Luscombe, as almost immediately what started to come then was me—my personality, my quirks, and Tim Curry was sort of left behind. Yet, at the same time, you always want to tip your hat to the person who made it so brilliant in the first place. So . . . it’s a really nice mix.

Bedella aside, the show was also distinguished in its borrowing (from the last months of the Broadway production) the notion of a constantly rotating Narrator. Across the new show’s eighteen-month life span, some of the best-loved names in British television—and beyond!—rolled out to celebrate the events of that dark and stormy night: comedian Russ Abbot; presenter Michael Aspel; astrologer Russell Grant; former soccer player Andy Gray; actors Ian Lavender (Private Pike in Dad’s Army) and Roger Lloyd-Pack; soap stars John McArdle (Brookside), Shaun Williamson (EastEnders) and Clive Mantle (Holby City); League of Gentlemen comic Steve Pemberton; former Young Ones star Nigel Planer; and Christopher Biggins, thirty years on from his “even if you don’t blink, you’ll probably miss him” appearance among the Transylvanians in The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

The original cast remained with the show through the end of 2006, and a Christmas season at the same Comedy Theatre that housed the final incarnation of the 1970s show; an action-packed run that also included the entire cast, plus Roger Lloyd-Pack and Richard O’Brien, performing “The Time Warp” live in London’s Trafalgar Square as part of the charity-driven Big Dance event on July 22, 2006.

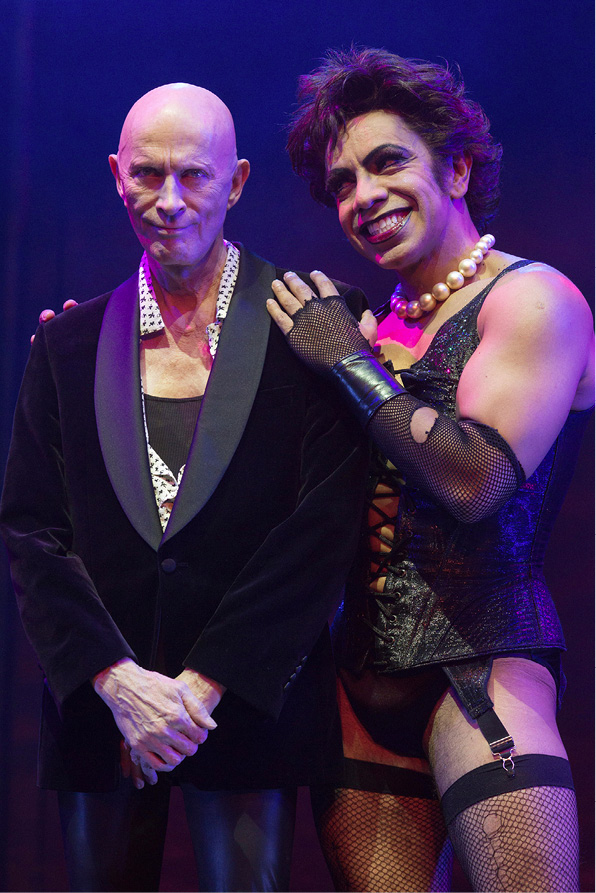

David Bedella (Frank) with narrator Richard O’Brien at the Palace Theatre, London, September, 2015.

© Vibrant Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo

A tour followed, wrapping up after almost a year and a half on the road, and then resuming once again in September 2009, for another fifteen months—a time span that also included director Luscombe’s creation of a whole new production in Seoul, South Korea, featuring a primarily Australian and New Zealander cast, but with local celebrities revolving through as the Narrator.

This outing would play until November 2010, originally in Seoul, but wrapping up with a five-week New Zealand tour. There, an extra special surprise for audiences emerged in the shape of Richard O’Brien taking the stage as the Narrator and, across the final week of the run, Richard Meek and Haley Flaherty, the British tour’s latest Brad and Janet, who flew out to join the production within days of their own show wrapping up.

Not every new production was a success, however. In 2008, director Gale Edwards’s vision of Richard O’Brien’s Rocky Horror Show premiered at the newly opened Star Theatre, part of the Star City Casino in Sydney, just a week after the nearby George Street Cinema finally halted its long-running showing of the movie, due to declining attendances.

The problem with the stage show, however, was not necessarily an overflow of audience fatigue, as the Sydney Morning Herald explained. Director Edwards, tiring of “the loud and smutty pantomime” that The Rocky Horror Show had become elsewhere, “tried to tap into the show’s subversive spirit [by casting] indie icon iOTA [another Hedwig graduate and a leading underground rock figurehead] as Frank and [cabaret performer] Paul Capsis as Riff-Raff.”

The result was a show high on dramatic undercurrents and symbology, but low on cheap laughs—so low, said the newspaper, that “O’Brien and his British producers disliked it to the point where they came in at the last moment and made sweeping changes to key scenes.”

From the point of view of preserving the integrity of the franchise (for what else has The Rocky Horror Show become?), the prohibition made sense. People attend the performance expecting to receive a certain kind of entertainment, and the academics among us can argue all night as to whether the show has evolved or devolved from its dark and dingy beginnings on a tiny London stage. It is what it is, and it is highly unlikely that it would ever have survived had it not proven itself so adaptable.

Edwards’s vision, while certainly dicing with the unfamiliar, was closer in spirit to the show’s origins than the show itself had been since the 1980s—a state of affairs that O’Brien himself engineered when he arranged for the play’s original libretto (published within Samuel French’s Music Library series) to be deleted and replaced with his revised version in 1999.

So much of the modern Rocky Horror experience was being played for laughs, or the demands and expectations of the audience, that even a deviation back to its original sense of deviance could be considered a betrayal by the fan club.

The revised production would open on schedule and run until the end of the summer, after which it transferred to Melbourne. However, plans to follow through with additional visits to Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth fell through. It’s hard to run without your heart and soul.

Rocky gets raunchy with this imaginative tribute movie. Author’s collection

Better When It All Began?

Christopher Luscombe remained at the directorial helm when The Rocky Horror Show returned to Britain’s stages in 2012 to celebrate its fortieth anniversary. A new cast was drawn partly from past productions (return engagements for Kristian Lavercombe, Abigail Jaye and Ceris Hine reprising the roles of Riff-Raff, Magenta and Columbia respectively); and partly from reality/soap-sourced newcomers—Ben Forster, a recent winner of the series Superstar (Brad), Rhydian Roberts from The X Factor (Rocky) and Roxanne Pallett (Emmerdale) as Janet.

Ballet dancer Oliver Thornton, meanwhile, represented an even more lithe and light-on-his-feet Doctor Frank-N-Furter than even Robin Cousins had mustered.

But is that what the show required? Tim Curry once described his personification of Doctor Frank-N-Furter as being more like a truck driver than anything else, particularly once the sweat had reduced his makeup to mush.

A man who regarded a squirt of 4711 as the height of olfactory sophistication, and who regarded Michelangelo’s finest accomplishments as fitting decoration for the bottom of his pool.

A man who probably thought ballet was somehow French for “testicles.”

We are not talking sophisticated tastes, here. Frank was, is, and forever should be what the Brits would term “a bit of rough,” and that was The Rocky Horror Show’s magic. To the average onlooker, it was the ultimate one-night-stand with an utterly inappropriate partner, down and dirty and nothing you’d want to think about in the morning. So you had to keep returning, just to make sure it actually happened.

It is not a pantomime, it is not a circus. It is not, as Jim Sharman told Curry in rehearsal one day, an opportunity to “throw Fantales to the kiddies.”

Unfortunately, nobody remembers that.

Tom Woodger, witness to an early performance in London, explains. “I saw the show again more recently, but by now it had become a far more ‘showbiz!’ affair, far less weird, far more glitzy.” When he first saw The Rocky Horror Show, few of the audience knew what to expect. Now, “the audience all knew what they would be seeing, and were joining in like the Kids from FAME, calling out in chorus, throwing their rice and so on, in a smug, self-congratulatory sort of way. It was like watching a punk band do cabaret.”

Nor is he alone in his disappointment.

Reporting back on the fortieth anniversary production’s opening night in Sydney, Australia, in April 2015, Daily Reviewer critic Ben Neutze shuddered, “[It is] basically the cartoon version of the iconic . . . film. There are costumes by Sue Blane which turn the volume up on the film designs—for example, Janet’s pink dress is now a far brighter pink, and she has Carol Brady hair—and a small, versatile set by Hugh Durrant, framed by giant rolls of old film. Visually, at least, it’s all rather sanitised.

“Where’s the scrappiness?” he demanded. “There’s a carefully torn show curtain, but not a ripped fishnet in sight.”

And Rocky without the fishnets surely is like Hair without any hair. But one cannot argue with success, no matter how much one might want to.

Rocky in Wimbledon, London, 2009.

Author’s collection