The closure of the London production of The Rocky Horror Show in September 1980 meant that for the first time in seven years, absolutely nobody was doing the time warp, at least on an official basis.

Unlicensed amateur productions of the show were still taking place, but it was the movie that dominated people’s thinking now, and the movie whose songs and direction were increasingly shaping many fans’ notion of “how it should be done.”

Even today on YouTube, posted excerpts from any of the many different productions that have taken place over the years will be greeted with at least one disgruntled commentator, insisting that the movie version is infinitely “better,” “stronger,” “more professional” and so forth.

Of course, YouTube did not exist in 1980, but Michael White and Lou Adler were nevertheless aware that the “true” Rocky Horror Show, the original Theatre Upstairs production that White, in his autobiography, still insists was the greatest ever, was in danger of being lost.

Their solution? To recreate it and send it out on tour across the United States.

They even contrived to ensure that a certain sense of continuity would be maintained, by timing the new production’s opening, at the Harvard Theater in Boston, to take place just weeks after the London show closed. Posters for the production proudly proclaimed it to be “alive on stage from London.”

Dig deeper, however, and it readily transpired that this was an altogether fresh rendering, with a largely all-American cast and crew. Only Canadian-born choreographer David Toguri, who joined The Rocky Horror family for the movie before overseeing the Oslo production in 1977; director Julian Hope, fresh from The Rocky Horror Show’s 1979 UK tour; and Kim Milford, returning from the Roxy and Broadway productions, had any prior experience with the show.

The remainder of the cast and crew were all comparative newcomers.

As Janet, Marcia Mitzman arrived in Boston from the Broadway production of Grease, where she played perhaps the most un-Janet-like character one could imagine, rabble-rousing Betty Rizzo. Lorella Brina (Magenta and Trixie) had appeared in the TV movie How to Pick Up Girls. But Pendleton Brown (Riff-Raff), Frank Gregory (Frank-N-Furter), C. J. Critt (Columbia), Frank Piergo (Brad) and Steve Lincoln (The Narrator) were all fresh blood, and they were about to undergo a veritable baptism of fire.

It was a tight performance, true indeed to the earliest productions and script, from which even the later London performances had strayed somewhat. O’Brien’s original Royal Court draft was as tight as it had ever been, the pacing bristling with the sheer exuberance of a newborn tale.

But, true to White and Adler’s fears, audiences for The Rocky Horror Show seemed unable to separate it from The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

In their droves, and in full costume, they descended on the theater, packing all the necessary props and bedeviling the performance with their bellowed comments and bellicose interruptions. And they could not be hushed or fazed in the slightest, not even by the creeping awareness that many of their tried-and-trusted interjections had very little relevance to what was taking place onstage.

The cast was bewildered; audience members who were not privy to the private litanies of Rocky Horror fandom were perplexed, utterly unable to comprehend why such a competent cast of thespians was being subjected to such a barrage of coordinated insult and obscenity.

Why were they calling that poor girl a “slut”? Why was her boyfriend being termed an “asshole”? And maybe the Narrator doesn’t have that pronounced a neck, but is it really necessary to keep on reminding him of the fact? Today, audiences and cast alike are familiar with the rituals of The Rocky Horror Show; among the latter, some might even have indulged in such antics themselves.

In 1980, however, the cult was just a cult, and had yet to become a part of the mainstream consciousness.

The show didn’t stand a chance.

Reviewing it for the Harvard Crimson, at the dawn of its two-week run, James G. Hershberg wrote, “The Boston cadre of Rocky Horror fans seems to be greeting it with the respect and appreciation due the first draft of a recognized masterpiece—but not with the unmitigated love and devotion they display for the film each weekend at the Exeter St. Theater.”

Still, he did acknowledge that it was a great evening out and recommended that everyone do their best to see, and enjoy, it. Otherwise, he wrote, “There is no hope at all for you and you will end up like the student who, when asked what she thought of Rocky Horror, replied: ‘Something that should be seen. Once.’”

Unfortunately, there appeared to be a lot of people who felt that way.

Within weeks, it was apparent that plans for the tour to crisscross the country had been overly ambitious. The original itinerary scarcely blossomed, and so the Boston engagement was followed by short runs elsewhere in the Northeast, but little more before it marched on to California.

Still, there were some memorable stagings, with one especially emotional engagement being chalked up when The Rocky Horror Show became the last production ever to play the beautiful old Locust Street Theater in Philadelphia. Days after the actors moved out, the wreckers were scheduled to move in, demolishing the sixty-year-old playhouse to make way for a parking garage. The parallels with the show’s original homes in Chelsea were remarkable.

The Rocky Horror Show wrapped up the year at the Granada Theater in Chicago, but not until it reached the West Coast, and its spiritual second home in California, could the play be said to have met with any genuine success. The tour was finally put out of its misery at the Los Angeles Aquarius in April.

Betty Blokk Buster and Other Stories

If the United States appeared to have no interest in The Rocky Horror Show, elsewhere the fascination was gaining speed once again.

Just six months after he laid the American touring company to rest, David Toguri was working with designer Brian Thomson and producer Wilton Morely to give Australia a fresh taste of the magic. The cast album would be coproduced by Richard Hartley; Perry Bedden would once again don the mantel of Riff-Raff.

Again a tour was envisaged, and this time it worked. Opening in Sydney on October 6, 1981, The Rocky Horror Show transferred to Melbourne in January 1982, before moving on to Brisbane, Hobart, Adelaide, and Perth, not only filling theaters nightly but also setting the stage for Morley to reprise the production in 1984, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the show’s original Australian opening.

And what a celebration it was, because Reg Livermore was returning as Doctor Frank-N-Furter.

Coming off his Rocky Horror experience, Livermore leaped straight back into the spotlight with Betty Blokk Buster, a one-man show that effectively reprised the sights and sounds of the Weimar cabaret of 1920s Germany—with added Absolutely Everything. Riotously funny, ferociously outrageous and intensely personal, it was Livermore reliving his own, already lengthy, career through song, anecdote, costume and madness, all delivered from within a fully functioning circus ring.

Livermore acknowledged that it was a risky proposition—Sydney . . . indeed, Australia . . . had never seen anything like it; “a less-than-grand parade,” he explains on his website, “of tawdry variety acts: a makeshift fairground of life’s dinkum battlers, freaks and survivors existing in a kind of sideshow alley, but in this instance a backstage view of it, behind the scenes.”

Even more challengingly, an evening’s performance could stretch to three hours, “which moved some to remark it was just a wank. Others saw it as the coming out of a gay man.” But it proved riotously popular. Opening at the Balmain Bijou in Sydney in mid-April 1975, where it remained for eight months, Betty Blokk Buster followed up with appearances in Canberra; at the Perth and Adelaide festivals; wrapped up in Melbourne at the end of July 1976; and even spawned a sequel of sorts, Son of Betty.

The best of the press notices are still quoted in Livermore’s promotional material: “the most professional piece of theatre seen in this country”; “make[s] you laugh, cry, clap your hands, stamp your feet, thrill to his music and chill to your bones”; “one of the most extraordinary events in Australian theatre history”; and from The National Times, ”the greatest thing since Rice Bubbles”—the local version of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies. You know you’ve arrived when your act is compared to a snap, crackle and popular breakfast cereal.

The long-delayed The True History of Ned Kelly followed, a brilliant vision that was, perhaps, just a little too brilliant. An armor-clad, sheep-stealing, cop-killing bandit he may have been, but Kelly represents one of the Australian people’s most sainted heroes, and Livermore’s approach to his life and times sent a lot of preconceptions flying. Reviews and audiences alike were harsh, but whereas many performers might have repented immediately and ensured that their next creation was more populist, Livermore took the opposite approach entirely.

He conjured Sacred Cow, another one-man-show that essentially took every criticism of the earlier show—namely, that Livermore should rein in his imagination somewhat, and not simply run with every idea that passed through his skull—and pursued them to even more grotesque ends.

On a nightly basis, therefore, Australian audiences were introduced to such characters as Renee Ashfield, a nymphomaniac sex-change tennis champion; Norma Moore, a stewardess with Air Dingo airlines; Aunty Tom, a confused sexagenarian ineptly attempting to tape-record a message to a dying friend while growing increasingly uncomfortable about her own mortality; and an utterly talentless daytime TV star, Joannie Bigg.

Less than successful in Australia, Sacred Cow proved even more disastrous when Livermore took it to London in August 1980. Even before a more or less captive audience comprising the city’s sizable expat Aussie community, onlookers started out confused, grew ever more restless and abusive and, ultimately, walked out. It was an absolute farrago, as a most indignant Sydney Daily Telegraph quickly huffed: “The British must have a very dim view of the Australian entertainment industry after Reg Livermore’s appearance on the London stage. His foulmouthed humour and crude ockerisms had them booing and walking out. Mr. Livermore may rely on the language of the gutter to get his comedy across but in doing so he has done other Australian performers a disservice. There was a time when Australian talent was clean and wholesome—and none the poorer for it. Performers such as The Seekers made their name without destroying ours.” To which the aforementioned Renee Ashfield (who, ironically, was not featured in the UK stage show) had the perfect riposte.

Was she damaging Australia’s good name, she was asked?

“Ah, go to buggery!” she replied. “What good name? Actually, Australia is a bloody embarrassment to me.”

The failure of Sacred Cow did not dent Livermore’s reputation as a performer, however. He was still in London when he received a call inviting him to try out for the role of circus legend Phineas T. Barnum in the Australian production of the Broadway smash Barnum; and, with a PG performance delivered flawlessly every night, the excesses of the past few years were suddenly forgiven.

But they were not, so far as Livermore was concerned, forgotten, and in 1983 he delivered Firing Squad, a brutally funny but painfully lifelike commentary on the present state of his home country—deep in recession, politically foundering, internationally sidelined. It was “a black juggernaut,” said an admiring Sydney Morning Herald, and one that Livermore steered mercilessly over its audience’s most sensitive parts.

People either loved Firing Squad or they hated it; they found it either wildly hilarious or deeply depressing; and even the show’s admirers acknowledged that there was a lot more going on than one might have expected from Australia’s crown prince of outrage. As the Sydney Morning Herald continued, “[It is] a sustained cry of outrage and pain, [Livermore’s] white clown’s face as implacable as a skull behind the flicker of accusing eyes. The crimson highlights on his cheekbones look like open wounds. We watch Petrouchka as poet and moralist.”

A lovely night out for all the family, then. And exquisite preparation for his return to the laboratory.

From the moment Livermore took the stage, at the opening night of the new Rocky Horror, it felt as though he had never been away. In his autobiography, Chapters and Chances, he recalled, “I did again the Bette Davis jump into the auditorium that had been a defining moment in the original Sydney show; responding to mocking and derisive laughter brought on by one of Frank’s more emotionally charged and self-indulgent moments, I would suddenly hurl myself into the audience via a flight of conveniently placed stairs, to seek out the offending culprit.” He would then “lift him up bodily and shake the shit out of him, and not stop until he was man enough to apologize.”

Livermore loved every minute of it. He was home again.

The tenth anniversary show continued on into 1985, closing (as had its predecessor) in Adelaide. The following year, it reopened in New Zealand, with Doctor Frank -N-Furter now portrayed by the show’s own director, English actor Daniel Abineri; and with a young and utterly unknown Russell Crowe making his professional acting debut in the traditionally conjoined roles of Doctor Scott and Eddie.

As a teen, Wellington-born Crowe had already tried his hand as a pop star, releasing a couple of singles under the youthfully exuberant name of Russ Le Roq (which he still deployed during the play). He also appeared in the local production of Grease, which led in turn to his casting in The Rocky Horror Show, after he ran into some of his fellow actors as they returned from their own auditions for the new show.

They pointed him to where the casting call was still underway, and Crowe told Kaspinet.com,

I had my guitar with me, [but] I didn’t have a song prepared or any sheet music or anything, so I said to the bloke, “do you mind if I just accompany myself?” and he said, “No, that’s fine.” I did this song called “Rapid Roy the Stock Car Boy,” which is a . . . Jim Croce song, which is kind of irreverent and cool . . . I sang it on the stage and . . . Daniel Abineri . . . basically gave me the job. And I walked out of that theater at the end of the day and it’s like, “Holy Shit, now I’m a professional theatre performer,” right?

He also got to share the stage with a former prime minister of New Zealand. Robert Muldoon, who led the country between 1975 and 1984, appeared as the Narrator during the show’s opening week at His Majesty’s Theatre in Auckland.

Crowe would remain with The Rocky Horror Show, in New Zealand and then Australia, until September 1988, a total of 416 performances that included one production in which he also understudied Doctor Frank-N-Furter, and at least a couple of shows where he appeared in that role.

Another star was in the process of being born.

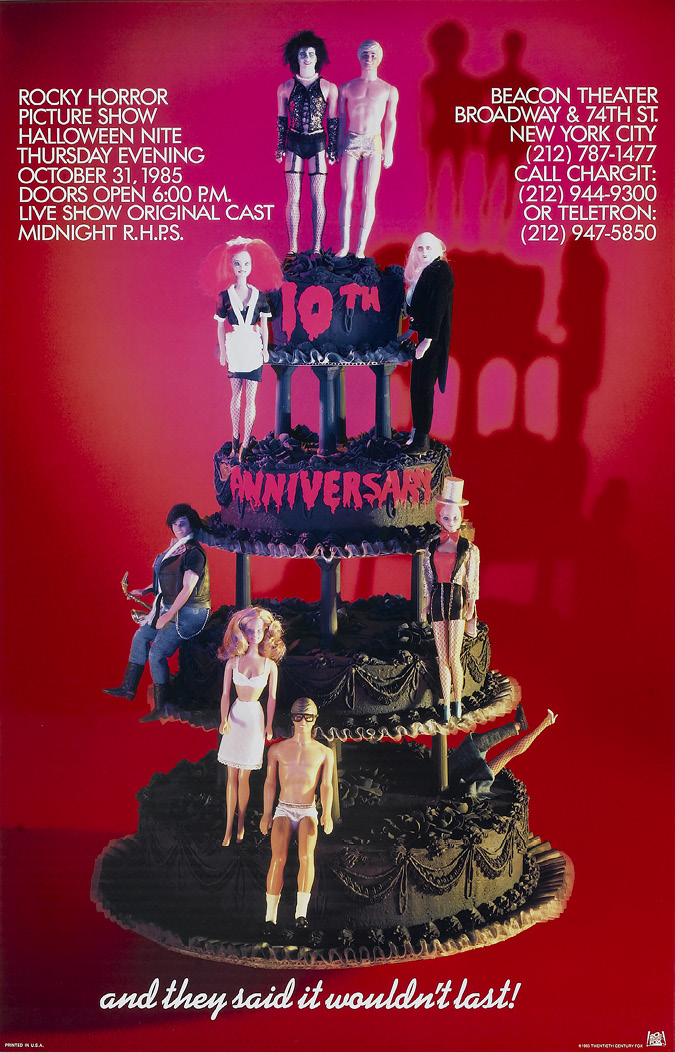

Rocky celebrates its tenth anniversary.

Author’s collection