Chapter 1

Zombies in Our Midst

I will break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; There will be confusion of people, those above with those from the lower depths.

I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; And the hosts of dead will outnumber the living!

—The Epic of Gilgamesh, ∼2700–2300 B.C.

The reason most people today are so scared of zombies could be a fluke of translation. The idea of the flesh-eating zombie depicted in modern-day books and movies originates from a 5,000-year-old epic, in which the goddess of love asks the father of gods to create a drought to punish the man who rejected her love. She then threatens to stir up the dead if her wish isn’t granted. Written in Sumerian, Babylonian, and other ancient languages, naturally there are multiple versions of the epic poem and different translations of those variations. While many translations depict zombies eating food “with” or “like” the living, some drop the preposition all together and have the creatures of the underworld eating humans directly. Zombie banks may not eat people or other banks, but their harm to society, the financial system, and the economy is just as scary.

The origins of the term zombie bank are much more recent than the Epic of Gilgamesh. The expression was first used by Boston College professor Edward J. Kane in an academic paper published in 1987. It referred to the savings and loans institutions in the United States that were insolvent but allowed to stay among the living by their regulators turning a blind eye to their losses.1 The term gained prominence in the next decade when it was more widely used to denote Japanese banks, whose refusal to face their losses and clean up their balance sheets was blamed for the industrialized nation’s so-called Lost Decade. During the financial crisis in 2008, bloggers, columnists, analysts, and even politicians began using it when talking about the weakest banks in the United States and Europe.

In its simplest form, zombie bank refers to an insolvent financial institution whose equity capital has been wiped out so that the value of its obligations is greater than its assets. The level of capital is crucial for banks, more so than for non-financial companies, because in the event of bankruptcy, a bank’s assets lose value faster and to a bigger extent. Thus, when a bank’s equity declines significantly due to losses, its creditors panic and head for the door (deposits are insured in most Western economies, so depositors don’t run away as easily). Capital is the size of the buffer that protects creditors of a bank from losses.

Even though technically, wiped out capital means bankruptcy and rules in many countries require the authorities to seize a lender in such a condition and wind it down, history is full of examples when that was not done. The dead bank is, instead, kept among the living through capital infusions from the government, loans from the central bank, and what is generally referred to as regulatory forbearance—that is, giving the lender leeway on postponing the recognition of losses.2 The intention is that economic conditions will improve and losses will be reversed; the bank will be able to make profits over time to cover the remaining losses and return to health.

Yet, there are many shades of gray when it comes to identifying insolvent banks. Publicly available balance sheets don’t always tell the whole truth. Kane, who was born during the Great Depression, says the outside estimates about a bank’s capital position can’t be exact, so when those estimates teeter near the point of insolvency, the bank will have a hard time borrowing new money. “You shouldn’t think of zombieness as just a one-zero event, that a bank is or isn’t, and that you can prove it,” Kane says. “When the estimates of the bank’s capital fall near the negative area, then people are not going to lend money to them at reasonable rates. Only the taxpayer will do that.”

According to R. Christopher Whalen, investment banker and author, a bank doesn’t have to be insolvent at all points in time to be called a zombie. Since early 2009, Whalen has been using the term to refer to the weakest U.S. banks. “When a firm fails and is brought back from the dead by the government and kept alive by ongoing support, then that’s a zombie,” Whalen says. The institution’s true return to health can only be tested when all government backing is off and it can stand on its own, he adds. “These zombies don’t eat people, they eat money,” Whalen wrote in March 2009.3 So we don’t have to worry about which version of the Epic of Gilgamesh to believe; it’s the taxpayer money that zombie banks eat and that’s where their harm to society is.

Because today’s banks are like black boxes, keeping many of their inner workings to themselves, it’s impossible to know whether they’re zombies for sure. Thomas M. Hoenig, who was a bank examiner at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City before becoming its president, says he could only tell whether some of today’s weakest banks are zombies if he could go in and examine them in the same detailed way. But it’s not even possible to examine the largest institutions, at least not in the detail Hoenig would like; if the same resources deployed to study the books of a small community bank were used for Citigroup, the third largest U.S. bank, 70,000 examiners would be needed, according to a Kansas City Fed analysis. About 20 inspectors try to do that job now on behalf of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and another 70 from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the two regulators responsible for monitoring Citigroup.

The Art of Keeping Zombies Alive

When banks face death due to surging losses in a downturn or financial crisis, authorities resort to multiple tools to keep them alive. Capital injections and liquidity provision are the most common. Governments invest in troubled banks when private capital shies away from doing so due to fears of insolvency. Since the 2008 crisis started, governments from the state of Bavaria to Switzerland to the Netherlands have put some $600 billion of capital into their banks.4 Although some of that has been paid back or replaced with private funds, as was the case with the largest U.S. banks, most of it still remains, and some nations, like Ireland, were pumping new cash into their institutions as this book was being penned. Central bank lending to weak firms is also crucial—at the height of the crisis, the total lending programs of the U.S. Federal Reserve totaled $8.2 trillion, with another $8.9 trillion of funding provided by the Treasury and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp (FDIC).5 While a majority of those have been wound down, $7.8 trillion were still outstanding as of October 2010, according to a tally by Nomi Prins, author of It Takes A Pillage: An Untold Story of Power, Deceit and Untold Trillions. Prins adds to that another $6.8 trillion of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae liabilities taken on by the government, arguing that the two mortgage finance giants’ rescue was, in effect, an indirect subsidy to the banks (Figure 1.1). If Freddie and Fannie had collapsed, U.S. banks would have been stuck with massive losses on their $2 trillion holdings of the two mortgage lenders’ bonds.6

Figure 1.1 U.S. government agencies’ spending to prop up the banking system and aid recipients, as of Oct. 2010.

SOURCE: Bailout Tally Report by Nomi Prins and Krisztina Ugrin.

At the end of July 2011, the European Central Bank (ECB) was still providing about $500 billion of short-term funding to the continent’s banks. Although the central banks argue such loans are backed by collateral from the banks, data released by the Fed in March 2011 showed that it allowed the use of $118 billion of junk bonds—those with non-investment-grade ratings, meaning higher risk of defaulting—as collateral by the largest banks borrowing from it.7 The same day that the Fed’s crisis lending facts were released, the ECB announced that it would suspend its requirement of accepting only investment-grade bonds as collateral to lend against Irish debt. It had exempted Greek sovereign bonds from its minimum-rating requirement a year earlier, just as rating agencies downgraded the country’s debt to below investment grade. That was akin to the ECB saying to Irish banks or others holding Irish government debt, “Don’t worry if Ireland’s sovereign risk is downgraded to junk; we’ll still accept its bonds, just like we accept Greece’s junk.” The ECB exempted Portugal’s government bonds from the rule in July 2011 when they were downgraded to junk ahead of Ireland’s debt. Ireland followed suit just a few weeks later.

The money that central banks use to stabilize markets and prevent panic also arrests the decline in asset values, even if that means a property bubble that was at the heart of the crisis to begin with cannot pop all the way. The Fed’s purchase of $1.3 trillion of mortgage bonds from January 2009 to March 2010 lowered interest rates on home loans in the United States and stopped the slide of housing prices, even if just temporarily. That slows the zombies’ bleeding from losses and lets them write some assets up in value and look solvent.

Another form of assistance to zombie banks is government backing for their debt, old and new. United States banks sold $280 billion of bonds backed by the government before the program was abolished at the end of 2009. European Union banks have used $1.3 trillion of state guarantees.8 While the explicit guarantees for the banks’ debt are being phased out in both continents, implicit guarantees remain. Because the U.S. and European governments have made it clear that they won’t let their largest institutions fail, even the weakest lenders are able to borrow private money. The German government’s implicit backing for its lenders raises the ratings of its banks by as many as eight levels, credit rating agency Moody’s Investors Service says. That means without the so-called support uplift, many would be rated below investment grade. In the United States that uplift is as high as five notches for Bank of America. Without the government backing, the bank’s rating by Moody’s would drop to just two levels above junk.9 “The litmus test to be considered truly alive is whether they’re able to function without government support of any kind,” says Whalen.

Perhaps the biggest subsidy given to all banks in Europe and the United States, though it particularly helps the zombies stay alive, is the near-zero percent interest rate policy maintained by the central banks on both sides of the Atlantic since the start of the crisis. The banks can borrow from their central bank at close to zero and then lend to their own governments at 4 to 10 percent. “That’s a backdoor subsidy, and the banks need that subsidy to repair their balance sheets,” says David Kotok, chief investment officer at Cumberland Advisors, a long-time critic of the policies. If the banks receive this cash injection long enough, they’ll be able to make enough profits to cover their losses from the crisis, some of which are still not recognized.

The delayed recognition of the losses is central to the life zombie banks live. Accounting rules are changed or suspended to let them push out some of their losses to future years; capital regulations are also put on hold to allow for time to rebuild capital; regulators reassure the public and investors that the banks are safe and sound, even when they don’t necessarily believe that. The two main agencies responsible for accounting rules in the world—the Financial Accounting Standards Board of the United States and the International Accounting Standards Board—rushed, in late 2008 to early 2009, to tweak regulations that would force banks to recognize declining loan values immediately, as defaults surged. Bank regulators around the world—compelled to tighten capital rules under public pressure—put off the implementation of harsher standards for five to 13 years, knowing that the zombie banks would need all of that time to fix their problems. Stress tests were conducted by U.S. and EU authorities to show that the largest banks were healthy enough to withstand another crisis. Even though both used optimistic assumptions about the future risks to housing markets and economic shocks, the U.S. test succeeded in assuring investors because it was perceived as full government backing for the top 19 institutions. The EU test failed to gain credibility because it found almost all banks to be healthy when the world knew there was a need for additional capital in many of them. The EU lost further face when the Irish banks, which were given a clean bill of health, collapsed two months after the second stress test in 2010.

Kicking the Can Down the Road

The biggest fear that politicians and regulators have when a bank nears death is the possibility of contagion—that the collapse will spook investors, depositors, and the public in general, causing a run on other banks. So the initial knee-jerk reaction by the authorities is to prevent the fall. Of course, not every failing lender is saved. Small banks around the world get taken over by authorities and wound down all the time; the FDIC in the United States has been seizing one or two every week since the crisis started. This is where the arbitrary judgment on whether a lender is big enough to pose systemic risk comes in. Each government and regulator has its own justification about why a rescue is merited, so there seems to be no easy yardstick for measuring risk. Because these decisions are arbitrary and politics plays a significant role, sometimes a smaller bank is rescued while a bigger one is let down. The Federal Reserve subsidized the takeover of Bear Stearns, the fifth largest U.S. investment bank, by JPMorgan Chase in March 2008. Yet six months later, Lehman Brothers, which was twice as big as Bear Stearns, was pushed into bankruptcy because politicians were given the wrong impression that its contagion would be smaller. Spain has refused to seize and shut down its cajas, dozens of small savings and loans banks that failed with the collapse of the country’s property bubble. Ireland rescued small lenders along with the nation’s largest.

There’s also a tendency by regulators and politicians to kick the can down the road because they most likely won’t be in positions of power when things blow up after a few years, says Kane. There’s also the gamble that, if asset prices recover, the economy turns around, and the zombie bank has enough time to plug its holes with subsidized profits, then it might actually stand on its own. Some of the savings and loans that were zombies did turn around and recover from their ills, Kane notes. And if the gamble on recovery doesn’t work, then hopefully the zombies’ collapse will be on the next guy’s watch. When crisis hits and asset values fall precipitously, banks argue that markets are overreacting, that the values of the mortgages on their books or the securities they hold are underpriced temporarily due to panicked sellers. They don’t want to be forced to sell at fire-sale prices and don’t want to mark down the remaining assets to what they consider as unrealistic values. Never mind that the declines are the result of an asset bubble popping, and that the corrections in values were long overdue. “When it’s a bubble being created, the market is rational, according to the banks,” says Joseph Stiglitz, who won the 2001 Nobel Prize in economics for his work on information asymmetry. “When the market realizes it was a bubble and starts to correct, then it’s deemed irrational.”

Banks’ oversized political clout, stemming from their increasing financial power, helps them convince politicians to rescue them. In the United States during the past two decades, the banking sector has outspent all others in campaign contributions and lobbying expenses.10 Financial institutions, their employees, and political action committees have given more money to politicians than the next four top spenders —health care, defense, transportation, and energy—combined. Bank executives have the politicians’ ears for other reasons too: Henry Paulson, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in 2008 when the latest crisis started, was running Goldman Sachs, the biggest U.S. investment bank, just two years earlier. Timothy Geithner, who replaced Paulson in 2009 as President Barrack Obama’s top economic official, was a protégé of Robert Rubin, who was among the group of executives running Citigroup when it teetered on the verge of collapse. It should be no surprise that, during a crisis, those officials turn for advice to people whom they know well.

Zombies and Lost Decades

It’s tempting to think there’s a chance that time will heal a zombie’s wounds and it will return to the living. However, the problems with letting the zombie banks fester far outweigh the benefits of a possible resurrection.

There are two opposite approaches zombie bank managers take as they struggle to bring their institutions back to life. They’ll hoard cash, make few new risky loans, and wait for the slow profit-building to pay for the losses over time. Or they’ll take much bigger risks with the hope that they can make windfall profits to plug the holes. The first was employed by Japanese zombie banks in the 1990s and is faulted for that nation’s Lost Decade, when the economy couldn’t resume growth after the property bubble burst because the banks wouldn’t lend. The latter was the choice of action by many savings and loans zombies in the 1980s in the United States as they “gambled for resurrection,” in Kane’s words. Although some of them won their bets and survived, most saw their losses multiply, making their final resolution even costlier for the taxpayer. We look at both cases and the lessons we refuse to learn from their experiences in the next chapter.

The propping up of institutions that should have died is unfair to healthy competitors. In a real market economy, those companies that take the wrong risks and lose out are supposed to fail, their customers and market share shifting to the surviving firms that were more prudent. In the United States, the credit rating uplift that Citigroup and Bank of America enjoy from their implicit government support lowers their borrowing costs, giving them an unfair advantage over the thousands of small banks that need to rely on their own strength for their ratings. Community banks have to pay more to borrow, because when they mess up and fail, they get taken over and shut down. As the ECB provides short-term loans to Irish banks and other zombies in its region in place of the wholesale borrowing they no longer can access because investors aren’t willing to risk their imminent death, banks that fund themselves through more expensive retail deposits lose out. “The business model that was challenged most during the latest crisis, the wholesale funding model, is being rewarded when it should really be punished, curtailed,” says Antonio Guglielmi, a bank analyst at Italy’s Mediobanca. To compete with the zombies, healthy banks end up taking bigger risks too.

When the zombies offer higher rates to lure depositors, healthier competitors may have to as well so as not to lose customers, thereby hurting their profitability and future health if those rates are unsustainable. The rescuing of failing institutions also creates or increases what’s commonly referred to as moral hazard—the propensity of managers to take risk without considering the negative consequences, since they believe the government will bail them out in case the risks blow up in their face one day. If the executives who run their firms to the ground keep their jobs and their companies are resurrected with taxpayer funds each time, then future executives will have very little incentive to worry about the risk-reward balance that is crucial to the functioning of a healthy market economy.

Letting zombies linger around also leaves the financial system vulnerable to aftershocks following a major meltdown. If the recovery takes hold with no hiccups, everything is fine, but too many times, the road isn’t so smooth. With zombies around, a second shock will drive down the confidence of investors and customers much faster and bring the financial system to the brink of collapse once again. As much as the public might hate the bankers now, the financial system plays a crucial role in the global economy, allocating capital and moving payments around. A frozen credit market, as we witnessed in 2008, can put the brakes on economic growth.

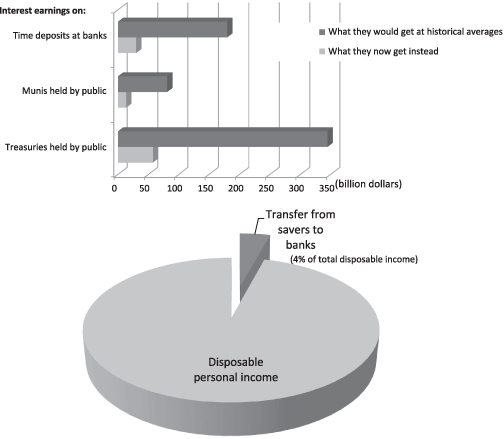

Keeping interest rates at zero in an effort to give the zombies time to heal their balance sheets has many harmful side effects for the rest of the global economy. It’s a wealth transfer from pensioners and others relying on the fixed returns of their savings to the banks’ coffers. That transfer reduces the disposable income for a section of society and thus their spending, which can become a major drag on the economy if it lasts for many years. Meanwhile, the rise in government debt is a wealth transfer from future generations, who are forced to pay for their predecessors’ mistakes. As in the case of Japan, which has kept its interest rates near zero since 1995, it can also settle in culturally, creating expectations of stable or falling prices and cause delaying of consumption or investment decisions. “Twenty years of zero percent interest rates change the psychology of consumers and savers,” says Todd Petzel, chief investment officer at New York fund management firm Offit Capital Advisors. Petzel has calculated that the wealth transfer in the United States equates to $500 billion for each year that rates stay at these levels (Figure 1.2).11

Figure 1.2 What U.S. savers lose each year due to the depressed interest rates, in effect transferring wealth to the coffers of the banks.

SOURCES: Offit Capital Advisors, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Traditionally, lower interest rates are central banks’ best weapon to stimulate economic activity. The thinking is that companies will borrow and invest when rates are lower; consumers will borrow and spend. Yet when there are zombie banks in the mix, the money provided at the low interest rate doesn’t necessarily trickle down to the consumers or the small enterprises. Zombies that borrow from the central bank at zero would rather lend to borrowers who can afford to pay higher rates since the zombie needs to heal its broken balance sheet as quickly as possible through profits. Thus, the current zero percent interest-rate policy has channeled funds to emerging market economies where returns are much higher, in double digits in some countries. That has caused overheating of their economies and could cause a crash the way Japan’s zero percent policy led to the Asian crisis of 1997–1998 when the free Japanese money found its way to neighboring countries.

Few people have made the connection, but even the events in the Middle East are an indirect result of the monetary easing in the West. Not only have the U.S. and European central banks kept interest rates close to zero, but they’ve also pumped trillions of dollars of extra cash into the global financial system. This policy of so-called quantitative easing has led to commodity price increases, including agricultural commodities. For the impoverished majorities of Middle Eastern countries, small increases in the cost of food can be devastating and served as a catalyst in the uprisings from Egypt to Tunisia. Last time around, when food prices surged, they came down fast with the financial crisis’s onset. This time, the Western central banks are determined to keep pumping money until their banks can earn their way out of death, which can keep food prices high for much longer and lead to further unrest in poor countries.

Bailing out zombie banks can even bring down countries that have been otherwise prudent. Ireland joined Greece in seeking help from the EU in 2010, not because its government spending had been prolific in the past two decades, but because it decided to back its banks that collapsed with the crash of a property bubble. Pumping money into its zombie banks, which have proved to be black holes, almost doubled its national debt and raised fears that it could not sustain paying such a heavy burden. Chapter 5 looks into Ireland’s troubles in more detail, and Chapter 6 contrasts Iceland’s way of handling its failed banks, by letting them go down.

It’s easy for politicians to make mistakes when faced with a crisis considering that decisions have to be made on the fly, with limited information at hand. Paulson and Geithner have said they had to rescue banks otherwise the world could have faced another Great Depression. Perhaps they were right initially—to prevent a total meltdown, temporary measures were needed. However, once the panic subsides, politicians need to seize the opportunity to finish off the business they couldn’t during the heat of the moment. That hasn’t been done in the three years that have elapsed since the crisis.

Gilgamesh, who was a very good king and loved by his people, made the ultimate error of rejecting goddess Ishtar’s love. The ensuing seven-year drought, which Ishtar got the father of gods to inflict through her threat of bringing back the dead, devastated Gilgamesh’s empire. Keeping zombie banks alive can wreak similar havoc on the world in the next decade. To prevent a lost decade like Japan’s in the 1990s, today’s politicians need to kill the zombies so the drought doesn’t last longer.

Notes

1. Edward J. Kane, “Dangers of Capital Forbearance: The Case of the FSLIC and ‘Zombie’ S&L’s,” Contemporary Policy Issues 5, no. 1 (January 1987): 77–83.

2. Edward J. Kane, The S&L Insurance Mess: How Did It Happen? (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press, 1989).

3. R. Chris Whalen, “Zombie Dance Party: Was the Banking Industry Really Profitable in 2008?” IRA Bank Monitor (March 2, 2009).

4. Figures based on Bloomberg LP data and calculations by the author.

5. Nomi Prins and Kristina Ugrin, “Bailout Tally Report,” Oct. 2010, www.nomiprins.com/reports/; Jan Hatzius, Zach Pandil, Alec Phillips, Jan Stehn, and Andrew Tilton, “U.S. Daily: Potential Consequences of a Downgrade of the U.S. Sovereign Rating,” Goldman Sachs research report, July 28, 2011.

6. Interview with Prins, October 18, 2010.

7. Matthew Leising, “Fed Let Brokers Turn Junk to Cash at Height of Financial Crisis,” Bloomberg News, April 1, 2011, www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-31/fed-accepted-more-defaulted-debt-than-treasuries-as-rescue-loan-collateral.html.

8. U.S. data from Bloomberg LP; EU data from the European Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/studies_reports/phase_out_bank_guarantees.pdf.

9. Moody’s Investor Service reports: “Germany,” October 14, 2010, and “U.S. Banking Industry Quarterly Credit Update—4Q10,” March 9, 2011.

10. Data from Center for Responsible Politics, www.opensecrets.org.

11. Todd Petzel, “The Invisible Tax—Zero Interest Rates,” Offit Capital Advisors LLC commentary, August 2010, www.offitcapital.com/commentaries/2010/august.htm.