Chapter 4

Germany’s Untouchable Zombies

When Roman Schmidt was preparing to start his first job after college in the early 1980s, his father was warned by one of his friends about the prospects of the bank that was hiring him. “Why did you allow your son to join a landesbank?” the friend asked Schmidt’s father at the time. “The landesbanks don’t have a business model. They’ll all merge or be wound down soon.” Schmidt didn’t stay at WestLB for too long, but the national discussion about the landesbanks continued. A few years later, a consultancy firm wrote a report to the German government basically reaching the same conclusion: they don’t have a sustainable model any more. The European Commission told the country around the same time that they were hurting competition in the region’s financial sector.

Kurt Seitz was working for another landesbank, Sachsen LB in the state of Saxony, when a board member came into his office in 2001 to talk about a great idea he had: investing in synthetic assets. Those would be bets on other assets, without ever owning the underlying security—a synthetic collateralized debt obligation (CDO) that would track the performance of some U.S. subprime mortgage bonds, for example. If the bonds did well, the CDOs would pay well. The bonds were all rated AAA, the highest possible. “Nothing ever happens to these papers,” Rainer Fuchs told Seitz, but Seitz was suspicious. He had studied debt crises in the United States and didn’t like the sound of leveraged wagers on somebody else’s bonds. He tried to discourage Fuchs to no avail. Sachsen LB piled on the synthetic stuff and promptly blew up in 2007 when the subprime market came crashing down. Seitz, like Schmidt, had left soon after that conversation, but he watched in sadness as his state’s landesbank went bust and was merged into a sister institution in 2008.

For some 30 years, Germany has been debating what to do with its troubled landesbanks. Many failed and were rescued by the state or federal governments multiple times over the years. Most of them took similar hits, like Sachsen LB during the subprime meltdown, but are still being propped up. They are exposed dangerously to the sovereign bonds of PIGS as well as their real estate markets and banks. Europe’s strongest nation, economically and politically, cannot get rid of its landesbanks, which almost everyone acknowledges serve no function for the economy any more. The landesbanks stand to win the title of the longest-living zombies in global financial history.

Landesbanks in the Land of Banks

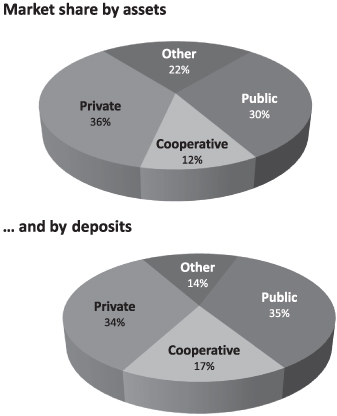

Germany’s banking system is the most complicated in all of Europe. While Deutsche Bank may be the largest bank and may have the most recognizable name outside of Germany, the country’s financial landscape is filled with hundreds of small institutions grouped in several different categories. Even after the 2010 acquisition of a domestic retail bank, Deutsche Bank’s share of its home market in most areas is less than 15 percent (Figure 4.1).1 There are three main groups of lenders in the country, legally recognized as such:

1. Public: This is the biggest pillar of the financial system and is built on 431 savings banks, or sparkasse. The landesbanks, owned jointly by the savings banks in their region and the states, are also part of this category. Originally almost each German land (state) had one, thus the name landesbank—the bank of the state. Through mergers the number has come down to seven.2

2. Cooperative: These 1,136 institutions are owned by their 16 million members, who are also depositors. The cooperatives also jointly own two central clearing banks.3

3. Private: This group includes the nation’s largest banks, such as Deutsche Bank, which are publicly traded. The second largest lender in the country and in this category, Commerzbank, has been partially owned by the federal government since it was rescued during the crisis and is considered in a special category of a semipublic bank by some.4 In mid-2011 Commerzbank started paying back the government.

Figure 4.1 Germany’s Crowded Banking Sector: Different groups’ shares of the national market as of February 2011.

SOURCE: Deutsche Bundesbank.

The landesbanks were founded at the beginning of the twentieth century. Their original function was to serve as a central clearinghouse for payments, making it possible for the hundreds of small savings banks to transfer money through the system. Over time, they expanded to provide lending and other banking services to larger companies that the savings banks were too small to serve. That involved the opening of branches in other countries since bigger clients, and even many of the small firms exporting their products, needed overseas connections. The landesbanks also entered the capital-markets business, originally as clients demanded the service. There was nothing wrong with the original model. The savings banks collected deposits throughout the country and made loans to consumers and small businesses. Yet, there was cash leftover from deposits, so that was channeled through the landesbanks to bigger companies, capital markets, and other investments. This way, the savings banks didn’t lose expanding local companies as clients to Deutsche Bank or other national institutions. The landesbanks were large and diverse enough to provide all the services that such customers needed as they got bigger and opened up to new markets. The two components of the public-bank system complemented each other.

Politics and Banking

The joint ownership by the state governments complicated the equation though. Local politicians had other functions in mind for the landesbanks. They wanted the lenders to support economic development in their region, contribute to local charities, and fund pet projects of the local governments. “It’s an anomaly that there are state-owned banks in Germany still,” says Jan U. Hagen, a finance professor at the European School of Management and Technology in Berlin. “Italian state banks were privatized successfully. France, Spain did the same. Germany is the least developed in this respect.” Eike Hallitzky, a member of the Bavarian state parliament and the committee overseeing the region’s landesbank, BayernLB, gives the following perfect example to this kind of political meddling.

Hallitzky recalls that Leo Kirch, a media mogul who used to own Germany’s largest TV station, needed to borrow €2 billion to pay for marketing rights of Formula 1 in 2001. Kirch first went to Deutsche Bank, which refused to lend him any more money since he was seen as pretty much bankrupt at the time and his empire was coming apart. So Kirch went to Edmund Stoiber, the ministerpräsident (governor) of Bavaria until 2007, asking for his help. Stoiber asked BayernLB whether it could make the loan to Kirch. The bank’s internal credit committee reviewed his finances and rejected the request for the same reasons as Deutsche Bank had. Stoiber didn’t give up though. He told his finance minister that the landesbank needed to make the loan. The finance minister went to the head of BayernLB and the loan was made. A year later, Kirch’s empire totally collapsed, owing billions to German banks, including the €2 billion loan made by BayernLB toward the end.5 “Why did Stoiber give the money?” asks Hallitzky. “Stoiber and Kirch were old friends. Also, Stoiber was running for chancellor in 2002, so he wanted to have his powerful friends and media backing him. That’s how politicians misused the landesbanks.”

Because the local politicians saw the landesbanks as their cash cows, they also pressed them to make more money so they could provide the funds when needed for these pet projects or political favors. That pushed them to take on bigger risks, such as investing in synthetic CDOs. State ownership also made their financing cheaper—the landesbanks’ bonds were guaranteed by their respective states, which brought down their borrowing costs. “They started out as clearing centers for the savings banks, but the political aspirations of the stakeholders changed their mission,” says Carola Schuler, who covers German banks for Moody’s Investors Service, the ratings agency. “They were saying ‘why not create regional banks to compete with bigger banks?’ Then ‘why not international banks?’ Especially because they had cheap funding due to government backing.”

Cheap Money, One Last Time

In 2001, under European Union (EU) pressure to end the favored status of the landesbanks, Germany agreed to phase out the state-backed borrowing and set July 2005 as the end to the practice. What that meant was the state banks had four years to fill up their coffers with guaranteed debt. This was a time when interest rates in Europe and the United States were extremely low, lingering around 1 percent. So the landesbanks went on a borrowing binge before the guarantees ran out, raising about €300 billion. Their combined balance sheets swelled to over €2 trillion, reaching the size of Deutsche Bank.6 Now, on top of the funds the savings banks sent their way, they had much more cash to lend and not enough customers in Germany to do so. They sought opportunities outside the country and found U.S. subprime markets, Icelandic banks, Spanish real estate, and more. They set up off-balance-sheet vehicles to get around capital requirements and offshore units to escape regulatory scrutiny.

SachsenLB, which was the smallest and newest of the landesbanks because it was founded after Germany’s reunification, established a subsidiary in Dublin’s financial services center, a tax oasis for banks from around the world. Irish banking regulators didn’t pay attention to SachsenLB’s activities in Dublin and neither did their German counterparts. That allowed the offshore business to invest in U.S. subprime securities almost 80 times its equity capital.7 “The daughter bank in Dublin was bigger than the mother in Leipzig,” says Karl Nolle, a Saxony politician, referring to SachsenLB’s headquarters in his state. In 2004, before Nolle’s party joined the ruling Christian Democrats in a coalition government to run the state, he wrote numerous letters to his party leaders, warning about the bank’s fishy business dealings in Ireland. “I told them 90 percent of profits came from this black box in Dublin; we need to find out what’s in it,” recalls Nolle. He was told that their new coalition partners didn’t want to dig into SachsenLB’s doings. “All parties liked the money from the landesbanks coming in,” Nolle says, adding that the country’s central bank and banking regulators were also sleeping at the switch. When SachenLB collapsed, it was sold to Landesbank Baden-Württemberg (LBBW), which took on the losses and risks. Nolle says it was a political favor by the neighboring state’s ministerpräsident to his counterpart in Saxony, Georg Milbradt, who resigned soon after the bank’s sale. LBBW lost €2 billion in 2008 following the merger and another €1.8 billion in the next two years.

Other landesbanks also invested in the U.S. subprime market, mostly through complicated instruments such as synthetic CDOs, and they lost even more than SachsenLB. The total subprime losses of the group were $40 billion, and half of that was BayernLB’s. The states and the federal government injected $31 billion into them as well as providing some $300 billion of asset and liquidity guarantees.8

Even the EU Can’t Shut Them Down

Like SachsenLB, WestLB was among the earliest casualties of the subprime crisis because of its bet on the U.S. housing market through complicated securities that blew up first. Although the other landesbanks that ran into trouble were rescued by their owners—the state governments and the savings banks—WestLB got a capital injection from the federal government. The EU’s competition commissioner started an investigation into the state support for WestLB in 2008.9 According to EU treaties, member countries cannot prop up their banks in a way that provides unfair advantages to that individual bank over its competitors. Ending the state guarantees for the landesbanks in 2005 was the culmination of an earlier investigation by the competition authority, following complaints by the so-called private banks in Germany.

Joaquín Almunia, the EU commissioner, has pretty much ruled that the bank isn’t viable under its current format and asked for the sale of the bank or a fundamental restructuring plan. Efforts to sell WestLB have failed after potential buyers were only interested in certain businesses of the lender and not the whole institution. Even after shrinking by about 30 percent, including the transfer of its most toxic assets to a bad bank set up by the federal government, the bank has €192 billion of assets. Almunia has ruled that the authorities overvalued the securities and loans that were shifted to the government’s bad bank. Even after getting rid of the bad stuff, WestLB still lost money in 2010.

The bank cannot be sold as a whole because, once out of government ownership, its funding costs would surge and it would lose even more money in coming years. Moody’s would lower its credit rating for WestLB from A3, which is still investment grade, to B2, which is five levels below investment grade, when government support is absent. Fitch Ratings would do the same, lowering it to subinvestment level.10 The assets are also funded by the extra deposits from the region’s savings banks, which would also disappear once it’s out of the public banking system, says Michael Dawson-Kropf, Fitch’s German banking analyst. “It’s a business model that only makes sense in state ownership,” he says. That hinders even the sale of subsidiaries, which investors have shown an interest in buying. The bank refused to sell its commercial real estate lending unit in 2010, saying the offers were too low.11 The real story was that potential buyers were asking for state-backed financing for three years after the sale, Moody’s analyst Schuler says. The government balked at providing such a guarantee, and the bidders dropped out. The EU had demanded the sale of the unit by the end of 2010. The country had to ask for an extension to the deadline.

Almunia had given Germany until February 2011 to come up with a final plan on what would be done with WestLB as a whole. Three plans were submitted, including one that the bank’s management favored and pushed for, basically shrinking the balance sheet further and continuing as before. The commissioner didn’t find them specific enough and requested a single blueprint by April. That one foresees a much smaller bank, about one-fourth the size of today’s bank, focusing on regional banking and serving the savings banks.12 That was what the federal government was pushing for earlier, but couldn’t get the state of North Rhine-Westphalia—the owner of WestLB—to agree to. Political bickering continued until the last moment, threatening a standoff with the European Commission. The state government failed to get the regional parliament’s backing for the revised plan in an initial vote, scrambling to make tweaks to garner support. Steffen Kampeter, Germany’s deputy finance minister, who has been holding negotiations with Almunia, complains of the indifference by local officials to EU demands. “For the European Commission, Germany as a nation is relevant. But the owners of the landesbanks are the states and the sparkassen. So we have a difficult type of discussion—on the one hand with EC and on the other with the state government and sparkassen, who don’t accept that the EC tells them what to do. They ignore the EC, as they have done for decades.”13

Almunia is also looking into BayernLB and HSH Nordbank, two other landesbanks, though neither the investigation nor the discussions have reached anywhere near those over WestLB. Hallitzky, the Bavarian parliamentarian, says the federal government has had very little influence over the years on the landesbank situation. His state’s governing politicians aren’t trying to resolve the BayernLB problem because they’re relying on the EU to do it for them, he suspects. “If the decision is negative, such as have to sell BayernLB, then the state government can point the blame at EU,” Hallitzky says.

Irish Connection 2.0

In addition to opening off-shore subsidiaries in Dublin’s financial services center, Germany’s landesbanks also made loans to the country’s banking and real estate sectors. At the end of 2010, German banks were owed $29 billion by Irish banks and $86 billion by other nongovernment borrowers.14 While specific breakdowns aren’t available, analysts suspect the landesbanks to be exposed greatly to Ireland’s financial and construction industries. The same is true for collapsing property markets in Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. German banks hold about €300 billion of commercial real estate loans—which financed office towers, shopping malls, hotels, or apartment buildings for rent—that are outside the country and those are “in all the hot spots all over the world,” according to Moody’s analyst Schuler. Most of that is exposure by the landesbanks, which invested all the €300 billion they raised before their state guarantees ran out in 2005 into such risky investments. “All that extra cash went to everything high-yielding at the time but turned out not to be high enough to compensate for the risk,” Schuler says.

So even if the EU stress tests assumed haircuts on PIGS sovereign debt held by the banks, they wouldn’t cover all the risks on landesbanks’ balance sheets. Because the landesbanks can’t handle a default by any of the Irish banks, Germany has pressed for their rescue and has opposed any haircuts for the banks’ bondholders—that is, the landesbanks. The banks’ balance sheets are so precarious though that they’ve been lobbying German regulators to oppose even the slightest bit of tightening in the definition of capital to be used in the stress tests.15 They were successful in getting German regulators to fight against such tightening during talks on global bank-capital rules. Bundesbank Vice President Franz-Christoph Zeitler, a former Bavarian central bank official, was one of the leading voices representing Germany at the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Zeitler, a strong defender of the landesbanks, was instrumental in getting other Basel members to agree to the phase-in period of over a decade for banks to replace their lower quality capital with common equity.

Hybrid securities, which count as debt for tax purposes and as equity for regulatory capital calculations, make up about one-third of most landesbanks’ capital. In WestLB’s case, they’re 76 percent of the total. These include so-called silent participations, which are unique to German banks. Like preferred securities in the rest of the world, silent participations don’t get voting rights, and their dividends can be put off when the firm is losing money. However, just as preferred shares didn’t prove to be truly loss absorbing during the latest crisis, the silent participations didn’t exactly act like equity capital. Their coupon payments were being made by some landesbanks even as the bank was recording losses, according to Fitch. The landesbanks were fighting for the recognition by the EU of such hybrid securities as capital in the 2011 stress tests, as they were in 2010. Otherwise, the capital holes in their balance sheets would come to light.

Not all landesbanks went on the borrowing binge and made risky investments with their money. A handful stuck to regional lending and has weathered the crisis fairly well. Helaba Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen and Nord/LB, which have avoided big losses, decided to convert their hybrid capital to regular equity in anticipation of the EU stress-test criteria.16 The ones that managed to stay out of trouble are, in general, majority-owned by the savings banks, which has limited meddling by the states, says Fitch’s Dawson-Kropf.

Other German Zombies

The landesbanks weren’t the only German lenders that blew up during the subprime crisis. Hypo Real Estate (HRE), which was spun off from HypoVereinsbank in 2003, fell apart in 2008 after lending to Icelandic banks and Lehman Brothers and after investing in CDOs and all other types of structured finance. Before its spinoff, HRE was a boring bank—issuing pfanbriefe, the German version of covered bonds, and funding commercial real estate projects in Germany. Covered bonds, which are collateralized by the property that the bank lends against, are considered the safest form of funding in European banking because they’re conservatively overcollateralized and have never defaulted. The German pfanbriefe were the model for the continent’s covered-bond market.

But soon after its separation from HypoVereinsbank, HRE shifted its focus to international lending and started borrowing from wholesale markets in addition to its pfanbriefe. In 2007, HRE bought DEPFA Bank, which was borrowing short-term to invest in long-duration sovereign bonds. DEPFA had moved to Dublin’s financial services center in 2002 to avoid regulation and taxes. HRE kept the unit there after the acquisition to continue taking advantage of both. By 2008, five years after its breakup, HRE had tripled its assets to €420 billion. When short-term funding for structured assets evaporated during the credit crunch, DEPFA collapsed. The bank also lost billions on its structured securities portfolio. The federal government bailed it out with €8 billion of capital injections and provided €124 billion of liquidity guarantees.17 Deputy Finance Minister Kampeter doesn’t want to justify saving HRE. He says the decision was made by the previous boss, Peer Steinbrück, the minister from 2005 to 2009. Others say HRE was rescued because it was a big player in pfanbriefe, having issued more than one-fifth of the total, and the government feared the collapse of the whole covered bond market.

The EU competition authorities want HRE to be split in two: public finance and real estate. In three to four years, the real estate unit could be merged with another bank doing the same thing, Kampeter says. Because the European Union hasn’t ruled that HRE as an unviable business, the government will let it live, Kampeter says. The bank has shifted €173 billion of toxic assets—including its portfolio of PIGS sovereign bonds—to a bad bank set up by the government.18 So the risks of the most problematic stuff are now on the shoulders of the taxpayer.

Commerzbank, Germany’s second largest, also lost big during the crisis and received the largest capital injection of all German banks. Struggling to be a bigger and better investment bank and to compete with its larger rival, Deutsche Bank, Commerz agreed to buy Dresdner Bank for €10 billion in 2008, just as the credit crisis was starting. Dresdner brought onto Commerz’s balance sheet wrong bets on the U.S. subprime market, adding to investments already going sour. The losses forced Commerz to seek government assistance twice. Paying big bucks for Dresdner, just when it needed capital to cover losses, increased Commerzbank’s vulnerability. Even insiders admit in private conversations that buying Dresdner brought the bank down. Germany injected €18 billion all together, more than twice the firm’s market value at the time.19

Just before embarking on Dresdner, Commerz had bought its partners’ stake in Eurohypo, a unit specializing in commercial real estate and public finance similar to HRE. Eurohypo has brought losses as well, and it gives Commerz a €17 billion exposure to PIGS sovereign debt. Although EU’s Almunia has ordered Commerz to sell Eurohypo, the bank hasn’t been successful so far, for similar reasons to WestLB’s failure to sell its commercial real estate lending business. It’s slowly trying to reduce its sovereign and commercial real estate exposures. The PIGS bond exposure declined by €3 billion during 2010.20 Commerz’s predicaments are similar to the landesbanks’ because they took similar roads, argues Berlin professor Hagen. “They entered risky businesses in early 2000s in an effort to avoid restructuring that was needed at the time,” Hagen says. “They took big risks to compensate for the lack of a model.”

Even as Commerzbank tries to raise capital to pay back the government— it would need to sell triple the amount of shares outstanding right now to cover the whole assistance package—it faces formidable challenges, such as the exposure to periphery countries and rising funding costs. Even though rating agencies bump up its credit score by three levels, thanks to the government backing (Figure 4.2), the bank’s subordinated debt has been downgraded recently after Germany passed a restructuring law that allows regulators to impose haircuts on bonds that are lower on the payment scale. Previously, the seniority of debt would only matter if a bank went bankrupt and was liquidated. Now, junior bonds could face losses even if the bank isn’t pushed into bankruptcy. In March 2011, when Commerzbank sold subordinated debt, it had to pay a 2.5 percentage-point premium over its senior bonds, compared to only 0.5 percentage points in the past.21

Figure 4.2 How German federal and local governments’ backing for banks lift their credit ratings, as of June 2011. The numbers in the uplift boxes show how many levels the government backing boosts a bank’s rating; for example, Commerzbank’s stand-alone rating of Baa2 is lifted by three levels to A2 due to government support.

SOURCE: Moody’s Investors Service.

Broken Models, Suffering PIGS

Germany’s economy was the fastest growing among the seven richest countries in the last decade, also called G7, according to some measures. Average income grew by close to 1 percent a year, outpacing the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, United States, France, and Italy between 2001 and 2010. Germany has recovered from the 2008–2009 global recession faster and more forcefully than other rich nations and its European partners.22 At first glance, these statistics fly in the face of historical precedents of how zombie banks hurt economic growth. But Germany’s zombie banks had fueled the spending binges in other EU countries, so not resolving the zombie problem hurts the economies of PIGS, not Germany. As they tighten their belts so they can pay back their debt to German banks, Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain are getting crushed under the weight, and the prospects of their recovery dim. Even Germany started sputtering when its economic growth fell to 0.1 percent in the second quarter of 2011.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other German politicians frequently talk about their support for the euro. That’s because the common currency has benefited Germany more than other EU countries, says James G. Rickards, who advises fund managers about the intersection of geopolitics and capital markets. The reunification of East and West Germany brought down labor costs in the 1990s, giving the country a competitive advantage when the euro was introduced in 1999, Rickards says. Meanwhile, the declining interest rates in the periphery countries enabled them to buy German exports with borrowed money, fueling the German export machine the country’s politicians are so proud of. The landesbanks, HRE and other lenders were part of this machine, funneling the extra savings of thrifty Germans. The machine has sputtered, even if the German economy hasn’t felt it yet.

Solving the zombie bank problem would shift more of the pain to German taxpayers. Because most of the state-guaranteed debt the landesbanks borrowed won’t mature until 2015, the debt-holders cannot be forced to share the losses during restructuring. Professor Hagen says the states don’t have the money to pay for such a true overhaul—closing them down and merging the central clearing function into one landesbank nationwide, which almost everybody agrees to be the solution. The savings banks, which hold equity stakes as well as some of the landesbanks’ unguaranteed debt, would face losses that could shake the most-trusted pillar of German banking, Hagen suspects. Dr. Thomas Keidel, a director at the association of savings banks, says his members would be willing to cough up funds for such a radical structuring of the landesbanks, but regional politics won’t allow it to happen. Merger talks between WestLB and BayernLB collapsed because Bavaria’s governor opposed it, people with knowledge of the discussions say. Regional leaders want to maintain their influence over their cash cows, says Bavarian politician Hallitzky. Another reason they have against such a major overhaul is the potential loss of jobs: 50,000 people work for the landesbanks.

What the federal government has done with WestLB and HRE—moving the toxic assets to a bad bank—is the first step of resolving zombie banks. In an economy that’s overbanked like Germany, there’s no need to keep the remaining good banks alive since their functions can be easily taken up by competitors, though it’s proven elusive to close WestLB and HRE so far. Taking on the bad assets of those two banks has swelled Germany’s public debt by roughly €300 billion, to 80 percent of national output, the highest level ever. Another €500 billion of toxic sludge from the other landesbanks would push the country’s debt ratio to over 90 percent. That wouldn’t necessarily mean the public debt would increase by as much because there would be some recovery in the bad loans and securities, deputy finance minister Kampeter says. WestLB’s bad loans will lose very little if they’re sold slowly, according to Kampeter. By 2028, there might be even a gain from some of the assets. “Unlike the Anglo-Saxon model, which wants to solve problems in 24 months, we want to solve them in 24 years,” he says.

Kampeter doesn’t seem to realize that sitting on the problems usually increases the costs for society, as previous zombie bank episodes have shown. Fitch’s Dawson-Kropf is worried that not enough is being done to fix the problems of the banking system before the next crisis hits. “They don’t seem to be aware of the time pressure when it comes to fixing the landesbanks,” he says. Constantin Gurdgiev, a lecturer at Trinity College in Dublin, thinks Germany is kicking the can down the road as much as possible to give its banks time to redeem their outstanding loans to PIGS and thus avoid the losses. For example, by 2013, there would be no Irish bank bonds held by German institutions because they’d be paid back, Gurdgiev says. German banks did cut their PIGS exposure by $96 billion in the fourth quarter of 2010, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Yet the reductions aren’t happening because the austerity packages in Ireland or Greece are helping those countries to pay back their debt so fast; rather, it’s mostly the result of the private debt being shifted to public debt as the ECB funds the PIGS’ banks and the EU lends to the governments.

So the losses will have to be faced sooner or later, and German taxpayers will still be on the hook when the ECB’s capital has to be replenished or the EU loans aren’t paid back. What’s more dangerous for Germany is the collapse of the euro, which has benefited the country immensely. Merkel might think she can save her zombie banks from dying, but she might lose her most precious jewel, the euro, while doing so.

Notes

1. Deutsche Bank, “Building a Retail Powerhouse in Europe’s Biggest Economy,” investor presentation, September 22, 2010.

2. Finansgruppe Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband, “Winning Through Trust: 2009,” Annual financial report, and “The Savings Banks Finance Group: An Overview,” March 2011.

3. Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken, “Liste aller Genossenschaftsbanken (Stand Ende 2010)” and “Jahresabschluss FinanzVerbund 2009.”

4. Christoph Kaserer, “Staatliche Hilfen für Banken und ihre Kosten—Notwendigkeit und Merkmale einer Ausstiegsstrategie,” working paper, July 29, 2010.

5. Leo Kirch accused Deutsche Bank of driving his firm to bankruptcy with public comments in 2002 that cast doubt about his creditworthiness. The lawsuit on the matter was unresolved in mid-2011 when Kirch died at the age of 84.

6. James G. Neuger and Robert McLeod, “Germany Agrees to EU Demand to Scrap Bank Subsidies,” Bloomberg News, July 17, 2001; Michael Dawson-Kropf and Patrick Rioual, “German Landesbanken: Facing an Uncertain Future,” FitchRatings research report, October 26, 2009.

7. Aaron Kirchfeld and Jacqueline Simmons, “The Dublin Connection,” Bloomberg Markets, December 2008, 101–109.

8. Katharina Barten, Claude Raab, Swen Metzler, Mathias Kuelpmann and Carola Schuler, “Germany,” Moody’s Investors Service, Banking System Outlook, October 14, 2010. Also Bloomberg LP figures.

9. European Commission, “State Aid: Commission Opens In-depth Investigation into Restructuring of WestLB,” EU press release, October 1, 2008.

10. James Wilson, “WestLB to Discuss Sale with Potential Bidders,” Financial Times, January 15, 2011; Laura Stevens, “WestLB Gets Ready to Cut Operations Back to Core,” Wall Street Journal, February 17, 2011; European Commission, “State Aid: Commission Extends Investigation into WestLB’s Bad Bank and Restructuring,” EU press release, May 11, 2010; Barten, Raab, Metzler, Kuelpmann, and Schuler, “Germany”; Fitch Ratings, “Resolution of WestLB’s RWN Requires Greater Clarity on Ownership and Business Model,” Press release, February 21, 2011.

11. WestLB, “WestImmo Sale: Bank Turns Down Current Offers,” press release, October 26, 2010.

12. Joaquín Almunia, “Landesbanken and the EU Competition Rules,” speech given in Berlin at 9th Handelsblatt annual conference, February 2, 2011; Niklas Magnusson and Oliver Suess, “WestLB Owners Propose Turning German Lender Into Verbundbank,” Bloomberg News, April 15, 2011.

13. The interview with Kampeter was in March 2011, between the two submissions of WestLB restructuring plans to the EU competition authorities.

14. Bank for International Settlements, BIS Quarterly Review, June 2011.

15. Laura Stevens, “EU Defends Stress Tests as Standards Draw Doubts,” Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2011; Aaron Kirchfeld, and Oliver Suess, “German State Banks Defend Silent Participations in Stress Tests,” Bloomberg News, March 10, 2011.

16. James Wilson, “Helaba Plans to Adapt Hybrid Capital to Withstand EBA Stress Tests,” Financial Times, April 21, 2011.

17. Hans-Joachim Dübel, “Germany’s Path into the Financial Crisis and Resolution Activities,” Center for European Policy Studies presentation, October 12, 2009; Barten, Raab, Metzler, Kuelpmann, and Schuler, “Germany”; Bloomberg LP data.

18. FMS Wertmanagement, “HRE Transfer to FMS Wertmanagement a Success,” Federal Agency for Market Stabilization press release, October 3, 2010.

19. European Commission, “State Aid: Commission Approved Recapitalization of Commerzbank,” European Union press release, May 7, 2009; Bloomberg LP data.

20. Commerzbank AG, Annual Report 2010.

21. Barten, Raab, Metzler, Kuelpmann and Schuler, “Germany”; Mathias Kuelpmann and Carola Schuler, “Moody’s Downgrades German Banks’ Subordinated Debt,” Moody’s Investors Service press release, February 17, 2011; “Commerz Feels Regulatory Bite as Premium Soars for Tier Two,” Euroweek, 1195, March 11, 2011.

22. “Vorsprung durch Exports: Which G7 Economy Was the Best Performer of the Past Decade? And Can It Keep It Up?” The Economist, February 3, 2011; International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook database.