Chapter 5

Ireland’s Zombies Bring the House Down

When delegations from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the European Commission arrived in Ireland in November 2010 to negotiate an aid package for the distressed country, the teams settled in the finance ministry building, a baroque structure with Roman columns in downtown Dublin. The staff at the ministry referred to the delegates as Germans, even though they hailed from various countries and only a few were in fact German nationals. But the name stuck because of the general sense among ministry staff that the actual negotiation was being held with Germany, which was calling the shots in the European Union (EU) and dictating the terms at the talks. Germany’s political leaders were in the finance ministry building in spirit, even if not physically present, the Irish felt. There were even jokes about whether the ministry staff needed to start learning German. Some of the “Germans” (the IMF delegation) were initially sympathetic to the possibility of the failed Irish banks defaulting on their senior debt, but the real Germans were dead set against it because of their banks’ perilous situation and exposure to that debt. The European delegations—from the ECB and the Commission—said that was not on the table. So the package that emerged from those talks ended up offering loans for the cash-strapped country to prop up its zombie banks even more, as well as an agreement that it would use national funds to the same end. Germany’s zombie banks were able to recover their loans to Irish banks while the Irish government took on more debt to keep its zombies going.

What brought Ireland to its knees in front of the IMF and the EU was an initial mistake of guaranteeing all the liabilities of its national banks at the height of the global credit meltdown in 2008. The government backing was meant to stop the flight of deposits and restore short-term financing to the Irish banks, and provided some temporary relief. However, as the underlying problems of the institutions began to emerge in the next two years, and the economy got worse, exasperating their losses, it looked like the government would have to make good on its pledge. That was enough to shake investor confidence in the sovereign credit because the liabilities that were backed were more than twice the size of the country’s gross domestic product. The banks were rescued all right, but now somebody had to rescue the country. The government of Prime Minister Brian Cowen, which was voted out of power in 2011, had two years to do something about the zombie banks after having secured a temporary respite from markets with the guarantee. The failure to deal with the zombies brought down the house of Ireland.

The new government, led by Enda Kenny, has been forced to follow in the footsteps of its predecessor because it relies on the IMF-EU funds while its banks survive thanks to ECB financing. While in opposition, Kenny and the Labour Party had promised the electorate they would make the German banks share the pain with the Irish people for the mistakes made during the boom times. Now the two parties’ leaders are resigned to continue implementing the austerity measures demanded by the IMF, and in July 2011 they managed to get the EU to lower the interest rate on their emergency loans as it did for Greece four months earlier. The country struggles to emerge from a three-year-long recession and continue paying its debt, which markets doubt it can. “Europe needs to understand the unemployment impact of all this austerity,” says Joan Burton, one of the most vocal critics of the previous government’s fiscal and financial policies and now a minister from the Labour wing of the coalition. “The important question for the Eurozone is—and this applies to Greece, Portugal, Italy, as well as Ireland: Can you construct a structure to help countries pay their debt? This is the EU’s first crisis, they haven’t figured it out yet.”

The Celtic Tiger’s Final Sprint

Ireland earned the nickname Celtic Tiger thanks to an impressive turnaround in its economic prospects following a bleak decade when rising unemployment and poverty led to waves of emigration from the country. In the 1990s, the Irish economy grew at an average annual rate of 7 percent, aided by changes in tax policies as well as EU membership and subsidies. The nation’s income per capita, which was two-thirds of the other advanced economies at the beginning of the decade, caught up with them by the end. But once they caught up, the Irish didn’t want to slow down. Because the fundamental reasons for the speedy growth had ended, they needed to find something else to spur another decade of it. The European monetary union going into effect around that time and bringing down interest rates for Ireland and the other periphery countries provided them the weapon. The Irish went on a construction and real estate binge, its banks borrowing from German and French banks, its consumers and developers borrowing from the banks (Figure 5.1). The housing boom—with a quadrupling of prices and the share of construction in the workforce doubling—helped maintain the country’s annual growth at a 6 percent average until 2008.1

Figure 5.1 Irish household consumption outpaced EU peers. Even the Greeks couldn’t keep up with it.

SOURCE: Eurostat.

The developers and the bankers became the most powerful and revered celebrities. They were aided by tax breaks and other public policies favoring investment in housing and homeownership. The two sectors and their executives had become untouchable, Burton says. Any attempts to curtail the building or the lending frenzy were quashed after heavy lobbying by the banks and the builders. When she or others tried to criticize either industry, they were ignored by supervisory agencies and the government. “There was a conspiracy of silence,” Burton says. When economist Morgan Kelly and a few others warned of an approaching housing bust in a series of newspaper articles in late 2006 to early 2007, Bertie Ahern, the prime minister preceding Cowen, derided those “moaning and cribbing about the economy,” adding that he was surprised “people who engage in that don’t commit suicide.” The governing politicians and the regulators often rubbed elbows with the businessmen in both sectors. Of course the taxes paid by the two industries filled up the public coffers—property-related tax revenue had jumped to 17 percent of the total in 2006 from 4 percent a decade earlier. In what became “ghost estates” after the crash, suburban residential developments surged, building up small villages near big cities.2

Anglo Irish Bank, a relatively newcomer to the financial scene after a merger of two small banks in 1986, led the way in lending to the developers. Sean FitzPatrick’s bank grew from €138 million of assets that first year to €97 billion in 2007—basically multiplying its balance sheet 700 times in two decades. Profit surged from €1 million to €1 billion in the same time period, all thanks to the housing boom and its lending to property developers. “Anglo was basically a monoline,” says Alan Dukes, who was appointed chairman of the bank after its collapse. “It had one business line only, and that was lending to property developers.” Initially the two big Irish banks, Bank of Ireland and Allied Irish Bank, didn’t want to emulate FitzPatrick, but when his profit machine kept churning out stellar results year after year, the other two couldn’t help but jump on the bandwagon.

While FitzPatrick opened the way for the lending bonanza to the developers, Anglo Irish didn’t lend to homeowners directly. The race to the bottom on that side—residential mortgage lending—was instigated by some of the foreign banks that had set up shop in Dublin’s financial services center. Bank of Scotland’s local unit slashed mortgage rates in 1999, starting a competitive race dubbed “mortgage wars” by the local media. Then, a small lender introduced 100 percent loan-to-value mortgages—the ability to get a home loan without putting any money down, as was popular in the U.S. housing market during its boom—and it spread like a virus, accounting for 36 percent of all mortgages taken out in 2006. By then, the share of property-related lending in the top three banks’ balance sheets had risen to 75 percent. Lending to consumers had jumped fivefold as 14 homes were built for every 100 people living in the country. While a handful of economists like Kelly warned of a crash, bankers, politicians, and most analysts talked of a “soft landing” that wouldn’t hurt the economy when the housing boom would end.3 Constantin Gurdgiev, a lecturer at Trinity College and also among the early voices warning about the brewing housing troubles, recalls a dinner party in 2006 when he was seated next to the then-governor of the Central Bank of Ireland. Gurdgiev asked the governor why he wouldn’t crack down on 100 percent loan-to-value mortgages. The reply was telling: “The government will never let me do this.”

The first shot across the bow came at the time of Bear Stearns’s collapse in March 2008, when the U.S. investment bank was sold at a weekend firesale to JPMorgan Chase. Anglo Irish stock took a beating the Monday after that sale, dropping 15 percent. Although it recovered later during the week, its slide for the rest of the year was consistent, losing about half its value in the next six months. The same happened with the other Irish banks’ shares, as investors concerns about their well-being rose when the housing prices started falling and the economy entered a recession. The banks also faced difficulty renewing short-term financing and turned to the ECB for funds while their corporate deposits were fleeing.

The Guarantee from Hell

After Lehman’s bankruptcy on September 15, the conditions of the Irish banks deteriorated further, Anglo Irish Bank being in the worst situation. Meetings between government officials and regulators that month involved discussions on whether to nationalize the lender. Pressure on politicians peaked on September 29 when Anglo Irish shares dropped 46 percent as well as sharp declines in all other Irish bank stocks. During meetings late into that night, led by Cowen and his finance minister, Brian Lenihan, the government decided to issue a blanket guarantee on the liabilities of all the banks for two years, including even the subordinated debt, even though their financial advisors from Merrill Lynch had suggested that wasn’t necessary. What motivated Cowen and Lenihan was to arrest the flight of deposits and renew confidence in the nation’s banking system. Following Lehman’s fall, the ECB was telling EU governments that they had to stand behind their banks as confidence eroded, some officials involved in the talks say. Thus, a strong signal had to be given to the markets that Ireland was behind its financial institutions. Nobody in the room was questioning the solvency of the banks, not even Anglo Irish’s. They were just looking at the problem as a liquidity crunch. So if financing was restored, the banks would be fine. Some of the meetings that night involved executives of the two biggest banks, Bank of Ireland and Allied Irish, though not Anglo Irish.

Members of the cabinet were roused from their sleep in the middle of the night and asked to sign their names to the decision. Opposition party leaders were told early next morning, some woken by phone calls around dawn. Even though the guarantee was brought to parliament for approval later that week, it was a fait accompli, not a real choice given to lawmakers, says Burton, who convinced her colleagues to cast the only dissenting votes, even though they were purely symbolic. Burton confesses that even she wasn’t aware of how big the problems with the nation’s banks were when she opposed the debt guarantee. She was uncomfortable with the cloud of secrecy behind the decision, the inclusion of subordinated debt, and the lumping of all the banks together, thinking only Anglo Irish was in trouble at the time. “I wasn’t aware of the level of destruction that has subsequently emerged in the other two,” she says now.

The guarantee provided a two-and-a-half-month respite for the banks only. Despite the guarantee, the banks still weren’t able to borrow or raise fresh capital from the markets, deposits continued to rush out, and shares continued falling. They also started admitting losses from their loans to the developers, and the authorities began to realize the problem wasn’t only liquidity. In December, the government announced its plans to inject €10 billion capital into the banks. A few days later Anglo chairman FitzPatrick resigned after revelations that he had personally borrowed €87 million from the bank without disclosing it publicly. In January, the government increased the amount it was planning to inject into the top three lenders and effectively nationalized Anglo Irish with the share purchase.4 But those were just the start. In the next two years, the Irish government had to put in €46 billion of capital into the banks as their losses piled up and their liabilities were backed fully by the state. The banks announced 2009 and 2010 losses that broke records in the nation’s corporate history. The bank recapitalizations, coupled with the collapse of property-related tax revenues, caused Ireland’s debt to more than double to 96 percent of annual economic output. With no end in sight to either the banks’ losses or the economic downturn, investor concerns about Ireland’s ability to pay its debt increased, pushing its borrowing costs up. Eventually Cowen’s government was forced to request an emergency loan package from the EU and the IMF in November 2010, similar to Greece’s six months earlier.5

You Can’t Burn the Creditors

By the time the IMF delegation rolled into town, the blanket bank-debt guarantee had expired, since it was only for two years, starting in September 2008. Realizing how bad the losses were turning out to be, Finance Minister Lenihan wanted to share the pain with the debt-holders. The IMF folks thought it made sense too. In particular, Anglo Irish, which was being wound down slowly and becoming fully state owned, didn’t have to worry about returning to capital markets to borrow in the future, so why not burn its bondholders at this stage, the minister thought. The ECB opposed any losses on senior bonds and was very adamant about that line. “There was very little bargaining in the real sense anyway,” said one of the Irish officials who was in the room, recalling the talks a year later. “Take it or leave it, they basically told us. Could we have gone against the wishes of the ECB, which we relied on for funding greatly? No, we couldn’t have.” Some junior bondholders had incurred losses during voluntary swaps by the banks, but the line on senior debt was very hard. The ECB was concerned about contagion. The central bank was worried that a default on senior debt by the Irish banks could lead to Spanish banks losing their access to funding (and some already have because of troubles with the banking sector there).

Two months after the package was sealed and the bondholders protected once again, Joe Higgins asked European Commission President José Manuel Barroso why saving the lenders to the Irish banks and making the people pay for their reckless lending was sound policy. Barroso, in a heated response to the Socialist deputy representing Ireland in the European Parliament, defended the EU response to the crisis by saying the problems of the Irish banks were completely of their own making and the union was just trying to help a member country.6 “The reason Barroso got so angry is because there’s no moral justification,” says Higgins, who’s now a member of Ireland’s parliament. “There’s no moral justification to put on the public’s shoulder the billions of euros of bad gambling debts by European banks because of private deals they made with private banks and private developers for private profit.” Higgins says he has also been shocked by the secrecy surrounding who the bondholders of the banks are. He called the banks one by one, trying to get lists of their creditors, and was told each time that was confidential information.

Since 2008, Irish banks have been paying off their debt as pieces of it come due, using the government’s capital injections as well as increased borrowing from the ECB and the Irish central bank. By March 2011, they relied on €160 billion of short-term financing from the two, which has halved their private debt in the past two years. That, in effect, transfers the future risk of Irish bank losses from their creditors—who were European banks, pension funds, and insurance companies, according to government officials—to the European and the Irish taxpayer. “ECB is becoming the EU’s bad bank,” says Desmond Lachman, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research in Washington. Even the risk that has been shifted to the Irish government could end up being EU’s problem, because Ireland is now borrowing from the union and the IMF since it’s been shut out of capital markets, according to Kevin O’Rourke, an economics professor at Dublin’s Trinity College and one of the few who predicted the crash early on. “We’re removing the bomb from one pocket and putting it in the other pocket,” says John Bruton, a former Irish prime minister. “It’s not Ireland versus Europe. There’s a resistance in Europe to look at the problem as a whole. Otherwise they’d realize that it’s actually Europe versus itself.”

Not So Innocent EU

When he raised his morality question to Barroso, Higgins says he wasn’t accusing the EU of having caused the Irish crisis. “Not that there isn’t plenty to blame the EU for—such as the deregulation of the banks they’ve been pushing for,” Higgins adds. Trinity Professor O’Rourke says the failure to establish an EU-wide banking regulatory regime was the “biggest design flaw” of the monetary union when it was set up. There was a lot of debate at the time of interest rates dropping for countries like Ireland and the fact that they’d lose the ability to devalue their currency in times of trouble, but nobody talked about cross-border bank resolution. The monetary union encouraged banks to go across borders and set up shop in other Eurozone countries, but they were left unchecked by local and home-country regulators alike, he says. “Who’s going to pay the bills when a bank that’s active in multiple countries? That’s an unresolved problem.”

The 1992 Maastricht Treaty that laid the foundation of the monetary union actually had provisions to give the ECB oversight role on the region’s banks, says former Prime Minister Bruton. The statue of the European System of Central Banks that accompanied the treaty had several articles that saw the ECB’s role as a macroprudential supervisor, coordinating with member-country central banks to make sure banks in countries where the economy was overheating were reined in.7 Germany tried to explicitly give such powers to the ECB in the late 1990s, but it was blocked by France, Bruton says. The French thought the ECB was too much of a German institution and didn’t want it to have wider supervisory power over the region’s banks. If the ECB had this mandate clearly, would it really use it to restrain German banks lending to their Irish counterparts during the country’s boom? While deregulation was the order of the day for most of the last two decades in the United States as well as Europe, banking regulators and central banks everywhere still had supervisory powers that could have led to precautionary measures, which they didn’t use.

The failure of bank oversight occurred at multiple levels in the EU, not just the result of a disengaged ECB. All the government-commissioned reports looking into Ireland’s financial crisis conclude that the country’s central bank and the banking regulator, Financial Services Authority (FSA), failed to see the economy’s overheating as well as the sector’s role and growing risks alongside it.8 “The regulator was just a cheerleader for a great little banking sector in a great little country,” says Minister Burton. “They never asked the question of how a bank can grow 35 percent a year.” The FSA didn’t regulate the foreign banks that set up shop in the International Financial Services Centre overlooking the River Liffey in Dublin, and neither did their home regulators. When DEPFA, the German Hypo Real Estate’s Irish unit, was falling down in 2008, Irish officials were worried that they’d also have to rescue it because it was technically an Irish bank on paper. They were relieved when Germany came to the aid of HRE and thus DEPFA. The incident points to the weakness in oversight in all of Europe though. Banks fell through the cracks because everybody thought it was somebody else’s responsibility.

Zombies No More?

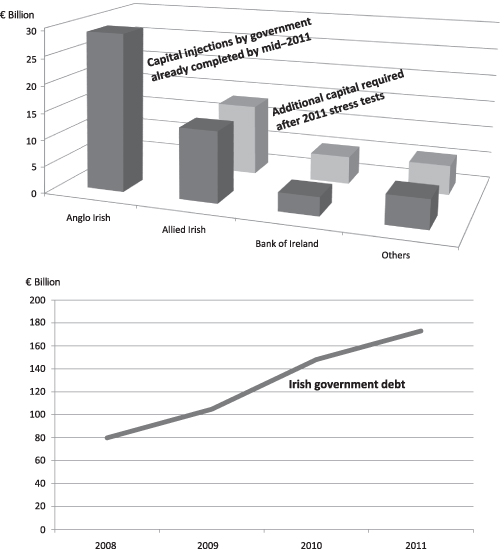

Even after €46 billion of new capital from the government, the Irish banks were not resuscitated. In March 2011, the central bank carried out a second stress test to see what additional capital they might need. Like all other bank stress tests, the aim was to convince investors that the banks had enough equity buffers to withstand further losses. The central bank ordered the remaining banks—Anglo Irish, in wind-down mode, was no longer included in the tests—to raise another €24 billion.9 About half of that was for Allied Irish Bank, most of which the government provided, thereby completing the nationalization of the second largest national lender. Bank of Ireland, the biggest lender, met its €5 billion requirement through a share sale, as well as by asking some of its bond holders to convert debt into stock to prevent falling into state control. By the end of July 2011, the Irish government had injected another €16 billion into its zombie banks, bringing its capital support to €62 billion (Figure 5.2).10

Figure 5.2 Money spent by the Irish government to prop up its ailing banks and the nation’s rising public debt. The capital required after 2011 stress tests might not all be provided by the government, as the banks struggle to raise private cash.

SOURCES: National Treasury Management Agency (Ireland), Eurostat, Financial Times, Bloomberg News.

The banks aren’t out of the doldrums because piecemeal fixes over the past two years have failed to get to the bottom of their problems. They need to be cleaned out completely. All toxic assets need to be put into separate bad banks so future investors and creditors know there will be no more surprise losses to the degree that has emerged since 2008. “Everything we’ve said about our banks has turned out to be worse, so it won’t be easy to restore our reputation,” says Minister Burton. Irish authorities did set up a bad bank at the end of 2009, targeting the loans to developers that began to sour before everything else. The National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) took over €71 billion of loans from five banks at an average 58 percent discount (i.e., paying 42 cents on the dollar for each loan). However, NAMA isn’t exactly a bad bank. In order to avoid adding the bad debt onto the government balance sheet already strained, Ireland set up NAMA to be majority-owned by private investors. Thus, instead of just taking the toxic stuff, the organization took over all the developer loans above a preset size, good and bad alike. That means the banks have lost some of their best performing loans while still being stuck with smaller nonperforming ones.11 Some developers whose businesses haven’t exploded and are still paying back their loans on time have sued NAMA to reverse decisions to take on their debt, arguing that has hurt their reputations. “It’s probably the worst model,” says Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics. “The bad bank is buying the good assets at discount prices while the government is left with the bad assets at the supposedly good banks.” Stiglitz testified at an Irish court in 2010 in favor of Patrick McKillen, one of those who have sued NAMA. McKillen won his court battle in 2011.12

The Crippled Housing Market

There are still about €170 billion of construction, developer, commercial, and real estate loans on the banks’ books, in addition to some €120 billion of mortgages. In the March 2011 stress tests, potential losses on those loans were calculated very aggressively, according to the Irish authorities. However, outsiders looking at the central bank’s “adverse” scenarios are somewhat skeptical that the worst case has been considered. The housing price decline that’s considered in the stressed scenario has already happened; the economic contraction assumed could be much worse; unemployment has already reached what was foreseen as the worst possible outcome, critics say. While the Irish economy contracted by 1 percent in 2010, the adverse case assumes a 0.2 percent shrinking. Unemployment hit 14.7 percent in the first quarter of 2011 whereas the 2011 “stressed” figure is only 14.9 percent.13 “None of these assumptions are very stressful,” says Karl Whelan, an economics professor at University College Dublin. The tests were better than the previous year’s exercise, but they still didn’t incorporate the worst possible losses, Whelan says. Trinity College’s Gurdgiev, who was among a group of academics briefed by the central bank on the tests, says the loss assumptions on mortgages weren’t too harsh either and that the differences in the types of outstanding loans weren’t taken into account.

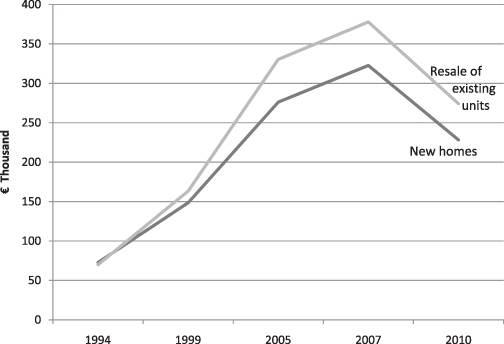

Ronán Lyons, an economist who tracks the housing market, says that in rural Ireland, prices don’t reflect reality because there are few transactions happening. So even though prices are down about 50 percent from their 2007 peak in places like Dublin, they still look as if they’re 20 to 30 percent down in many areas, he says. They need to fall much further before the market can stabilize, according to Lyons. Price-to-income ratios show that the average home price needs to decline by another 30 percent before reaching a normal level, some argue (Figure 5.3). Estimates of the number of homes stuck in ghost estates reach 300,000.14 Lyons says his estimate of 35,000, though not as scary, could still take five years to clear, which means prices will be depressed for a while. Even in downtown Dublin, there are plenty of ghost buildings. A stranger looking for an address in the financial district can run into, within the same block, half a dozen newly built, shiny glass towers whose doors are locked shut. Most of those office buildings never got any tenants after being completed around the end of the boom; some closed their doors after the company occupying the tower went bust.

Figure 5.3 Housing prices in Ireland more than quintupled in just over a decade. The roughly 30 percent decline from the peak so far might not be enough, many analysts say.

SOURCE: Department of the Community, Environment and Local Government (Ireland).

About three-fourths of the mortgages in the country are variable rate ones, based on ECB interest rates. As the ECB raises rates, they will reset higher, causing further difficulties for homeowners’ ability to pay, leading to more defaults and further price declines. Studies show that a one percentage point increase in mortgage rates reduces the probability of a housing slump ending by 10 percent.15 The rising ECB rates also hurt the banks, which rely heavily on borrowing from the central bank. A quarter-point increase in April 2011—from 1 percent to 1.25 percent—increased the banks’ borrowing costs by 25 percent, points out Anglo Irish Chairman Dukes. The ECB raised its rates by another quarter point in July 2011 to 1.5 percent.

The banks cannot come out of the hole until their balance sheets are fully cleansed of troubled loans and mortgages, according to Dukes. “Cleanup means crystallizing chunky losses, and government doesn’t have the money to do that,” he says, contrasting the slow pace of tackling problems in his home country to Iceland’s speedy cleanup of its banking system. Dukes recalls how the same slow approach was favored in the 1980s when Ireland faced fiscal problems. As finance minister, Dukes argued that the fix should be done fast and pain taken upfront, but his colleagues didn’t heed his view and took the slow road, which extended the pain for several years and cost them the next elections.

Will the Tiger Make It?

Dukes calculates the full debt burden on the taxpayer for the banks’ cleanup to be roughly €200 billion. The country can perhaps pay half of that in the next 10 years, he says. The other half has to be written off or spread over many decades to avoid a default, according to Dukes. “You can make slaves out of Irish people, but they still can’t pay that back,” says Socialist politician Higgins. Sarah Carey, a former columnist for the Sunday Times and Irish Times newspapers, says there will likely be a default in two years because the country cannot afford to pay, and, by then, Germany and France expect their banks to be healthy enough to absorb the losses. Irish government officials insist the country can pay. Ireland has made harsh fiscal adjustments in the past (such as in the 1980s) and can pull this one off too, they say. The Kenny government has been trying to get the interest rate on its EU-IMF loans reduced, but Germany has objected, demanding that Ireland bump up its corporate tax rate, the lowest in the union, in return for a rate cut. The low tax rate has helped Ireland attract foreign investment from global giants like Google, and increasing it would destroy its economy, the Irish say. “If Germany and France force higher corporate tax, we’ll have to turn ECB debt into equity in the banks,” says economist Lyons.

As in the case of Greece, austerity measures trying to cut the government budget deficit also hurt the chances of economic recovery and make it harder for Ireland to pay back. The impact of the three-year-old recession can be seen even better in poorer areas of Dublin, where shuttered storefronts sometimes fill up a whole block and “To Let” signs on houses and apartments are too numerous to count. Restaurant managers, storeowners, and salaried employees all make the same complaints: business is slow and taxes are higher, making it really hard to go on. Despite the setbacks, Ireland is multiple times better off than it was a few decades ago, says former Prime Minister Bruton. In the 1950s, when he was growing up in Dunboyne, a small town half an hour west of Dublin, there were kids who were going to school with no shoes on, Bruton recalls. Now there’s a train station, and even Lebanese and Chinese restaurants in his hometown. “We can afford the wealth to decline a little, so long as this burden is distributed fairly,” says Bruton. “This may require more progressive taxation as well as expenditure reductions.”

The “Germans,” that is, the IMF team, initially questioned why they were in Ireland because downtown Dublin looked so prosperous and like any other Western European city. Being used to setting up camp in the capitals of emerging economies that go bust often, many with incomplete infrastructure and visible poverty on main streets, the team members went through a culture shock at first. Ireland is clearly no developing country as it was in the 1950s, but there’s also no doubt that the Irish need to pay for the sins they committed during the latest boom years, which were a bubble, by giving up some of their comforts. But the numbers don’t add up if only they are to sacrifice while the German and/or French taxpayers are to be spared completely. Irish banks, companies, and consumers borrowed irresponsibly, but German and French banks lent the same way. So the pain needs to be shared by both sides. Meanwhile, Ireland has more to do to clean up its zombie banks, just like its EU partners.

Notes

1. International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook database; Patrick Honohan, “The Irish Banking Crisis: Regulatory and Financial Stability Policy 2003–2008,” Report to the Minister for Finance by the Governor of the Central Bank, May 31, 2010; Michael I. Cragg, Affidavit presented to the High Court Commercial in Dublin, court doc. number 2010 No. 909 JR.

2. Fintan O’Toole, Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Shane Ross, The Bankers: How the Banks Brought Ireland to Its Knees (Dublin: Penguin Ireland, 2009); Bertie Ahern, speech to the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, July 4, 2007, RTE News video clip.

3. Anglo Irish Bank annual reports; Morgan Kelly, “Whatever Happened to Ireland?” Vox, May 17, 2010; Ronán Lyons, “Ireland’s Economic Crisis: What Sort of Hole Are We in and How We Get Out?” Working paper, November 30, 2010; Honohan, “The Irish Banking Crisis”; Ross, The Bankers.

4. Sean FitzPatrick, public statement, December 18, 2008; Peter Nyberg, “Misjudging Risk: Causes of the Systemic Banking Crisis in Ireland,” Report of the Commission of Investigation into the Banking Sector in Ireland, March 2011.

5. Eurostat database; National Treasury Management Agency, “PCAR and Bank Restructuring to Rebuild Confidence in Ireland,” slide presentation, April 2011; Nyberg, “Misjudging Risk.”

6. Video clip of Barroso-Higgins exchange in European Parliament, January 19, 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=uah_BVTmHeM.

7. John Bruton, “The Economic Future of the European Union,” Speech at the London School of Economics and Political Science, March 7, 2011; John Bruton, “How Should Responsibility Be Shared for the Banking Crisis?” America & Europe, blog post, March 29, 2011, http://intercontinentalnetwork.blogspot.com/2011/03/how-should-responsibility-be-shared-for.html.

8. Klaus Regling and Max Watson, “A Preliminary Report on the Sources of Ireland’s Banking Crisis,” Government Publications, June 2010; Honohan, “The Irish Banking Crisis”; Nyberg, “Misjudging Risk.”

9. Central Bank of Ireland. “The Financial Measures Programme Report,” March 2011.

10. “Results of Rights Issue Rump Placement,” press release, The Governor and Company of the Bank of Ireland, July 27, 2011.

11. National Asset Management Agency (Designation of Eligible Bank Assets) Regulations 2009, Statuary Instruments, S.I. No. 568 of 2009; National Asset Management Agency, “NAMA Publishes Third Quarter Report and Accounts,” NAMA press release, March 2, 2011; National Treasury Management Agency, “PCAR and Bank Restructuring to Rebuild Confidence in Ireland.”

12. Joseph E. Stiglitz, Affidavit to the High Court Commercial, 2010 No. 909 JR, filed September 7, 2010; Donal Griffin, Jonathan Keehner, and Joe Brennan, “Bono Partner McKillen’s Suit May Hold Key for Anglo Irish Loans,” Bloomberg News, October 3, 2010; “Ireland’s NAMA Will Not Acquire McKillen’s Loans,” Reuters, July 15, 2011.

13. Central Bank of Ireland, “The Financial Measures Programme Report”; Eurostat Database; Central Statistics Office Ireland database.

14. Martin Walsh,. “Average House Prices Could Still Be Overvalued by Up to 30%,” Irish Times, April 25, 2011; Ronán Lyons, “2010 Marks the End of a Single National Property Market,” Daft.ie, January 5, 2011.

15. Agustin S. Bénétrix, Barry Eichengreen, and Kevin H. O’Rourke, “How Housing Slumps End,” Vox, July 21, 2010.