Chapter 4

Making Choices

IN THIS CHAPTER

Boring into Boolean expressions for fun and profit

Boring into Boolean expressions for fun and profit

Focusing on your basic, run-of-the-mill if statement

Focusing on your basic, run-of-the-mill if statement

Looking at else clauses and else-if statements

Looking at else clauses and else-if statements

Understanding nested if statements

Understanding nested if statements

Considering logical operators

Considering logical operators

Looking at the weird ?: operator

Looking at the weird ?: operator

Knowing the proper way to do string comparisons

Knowing the proper way to do string comparisons

So far in this book, all the programs have run straight through from start to finish without making any decisions along the way. In this chapter, you discover two Java statements that let you create some variety in your programs. The if statement lets you execute a statement or a block of statements only if some conditional test turns out to be true. And the switch statement lets you execute one of several blocks of statements depending on the value of an integer variable.

The if statement relies heavily on the use of Boolean expressions, which are, in general, expressions that yield a simple true or false result. Because you can’t do even the simplest if statement without a Boolean expression, this chapter begins by showing you how to code simple Java boolean expressions that test the value of a variable. Later, after looking at the details of how the if statement works, I revisit boolean expressions to show how to combine them to make complicated logical decisions. Then I get to the switch statement.

Using Simple Boolean Expressions

All if statements, as well as several of the other control statements that I describe in Book 2, Chapter 5 (while, do, and for), use boolean expressions to determine whether to execute or skip a statement (or a block of statements). A boolean expression is a Java expression that, when evaluated, returns a boolean value: true or false.

As you discover later in this chapter, boolean expressions can be very complicated. Most of the time, however, you use simple expressions that compare the value of a variable with the value of some other variable, a literal, or perhaps a simple arithmetic expression. This comparison uses one of the relational operators listed in Table 4-1. All these operators are binary operators, which means that they work on two operands.

TABLE 4-1 Relational Operators

Operator |

Description |

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

A basic Java boolean expression has this form:

expression relational-operator expression

Java evaluates a boolean expression by first evaluating the expression on the left, then evaluating the expression on the right, and finally applying the relational operator to determine whether the entire expression evaluates to true or false.

Here are some simple examples of relational expressions. For each example, assume that the following statements were used to declare and initialize the variables:

int i = 5;

int j = 10;

int k = 15;

double x = 5.0;

double y = 7.5;

double z = 12.3;

Here are the sample expressions, along with their results (based on the values supplied):

Expression |

Value |

Explanation |

|

|

The value of |

|

|

The value of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Casting allows the comparison, and |

|

|

Casting allows the comparison, and |

|

|

|

if (i = 5)

Oops. But Java won’t let you get away with this, so you have to correct your mistake and recompile the program. At first, doing so seems like a nuisance. The more you work with Java, the more you come to appreciate that comparison and assignment are two different things, and it’s best that a single operator (=

inputString == "Yes"

Note, however, that this is not the correct way to compare strings in Java. You find out the correct way in the section “Comparing Strings,” later in this chapter.

Using if Statements

The if statement is one of the most important statements in any programming language, and Java is no exception. The following sections describe the ins and outs of using the various forms of Java’s powerful if statement.

Simple if statements

In its most basic form, an if statement lets you execute a single statement or a block of statements only if a boolean expression evaluates to true. The basic form of the if statement looks like this:

if (boolean-expression)

statement

Note that the boolean expression must be enclosed in parentheses. Also, if you use only a single statement, it must end with a semicolon. But the statement can also be a statement block enclosed by braces. In that case, each statement within the block needs a semicolon, but the block itself doesn’t.

Here’s an example of a typical if statement:

double commissionRate = 0.0;

if (salesTotal > 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.05;

In this example, a variable named commissionRate is initialized to 0.0 and then set to 0.05 if salesTotal is greater than 10000.0.

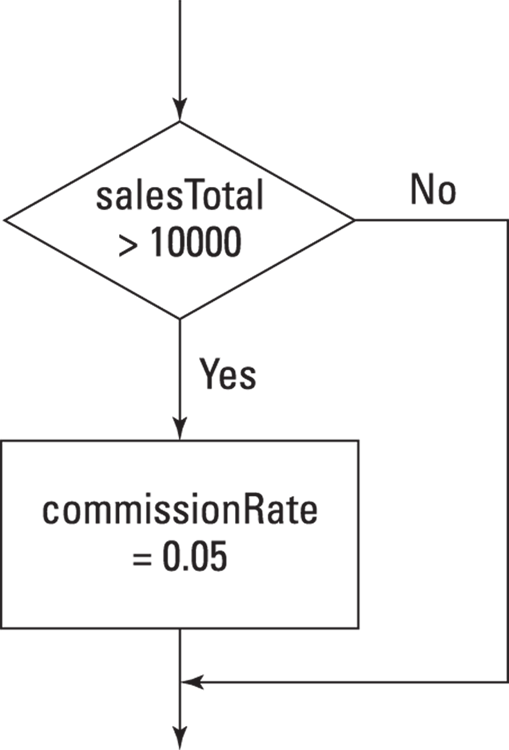

Some programmers find it helpful to visualize the operation of an if statement as a flowchart, as shown in Figure 4-1. In this flowchart, the diamond symbol represents the condition test: If the sales total is greater than $10,000, the statement in the rectangle is executed. If not, that statement is bypassed.

FIGURE 4-1: The flowchart for an if statement.

Here’s an example that uses a block rather than a single statement:

double commissionRate = 0.0;

if (salesTotal > 10000.0)

{

commissionRate = 0.05;

commission = salesTotal * commissionRate;

}

In this example, the two statements within the braces are executed if sales Total is greater than $10,000. Otherwise neither statement is executed.

Here are a few additional points about simple if statements:

- Some programmers prefer to code the opening brace for the statement block on the same line as the

ifstatement itself, like this:if (salesTotal > 10000.0) {commissionRate = 0.05;commission = salesTotal * commissionRate;}This method is simply a matter of style, so either technique is acceptable.

Indentation by itself doesn’t create a block. Consider this code:

Indentation by itself doesn’t create a block. Consider this code: if (salesTotal > 10000.0)commissionRate = 0.05;commission = salesTotal * commissionRate;Here I don’t use the braces to mark a block but indent the last statement as though it were part of the

ifstatement. Don’t be fooled; the last statement is executed regardless of whether the expression in theifstatement evaluates totrue. Some programmers like to code a statement block even for

Some programmers like to code a statement block even for ifstatements that conditionally execute just one statement. Here’s an example:if (salesTotal > 10000.0){commissionRate = 0.05;}That’s not a bad idea, because it makes the structure of your code a little more obvious by adding extra white space around the statement. Also, if you decide later that you need to add a few statements to the block, the braces are already there. (It’s all too easy to later add extra lines to a conditional and forget to include the braces, which leads to a bug that can be hard to trace.)

- If only one statement needs to be conditionally executed, some programmers use just one line for the whole thing, like this:

if (salesTotal > 10000.0) commissionRate = 0.05;This method works, but I’d avoid it. Your classes are easier to follow if you use line breaks and indentation to highlight their structure.

if-else statements

An if-else statement adds an additional element to a basic if statement: a statement or block that’s executed if the boolean expression is not true. Its basic format is

if (boolean-expression)

statement

else

statement

Here’s an example:

double commissionRate;

if (salesTotal <= 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.05;

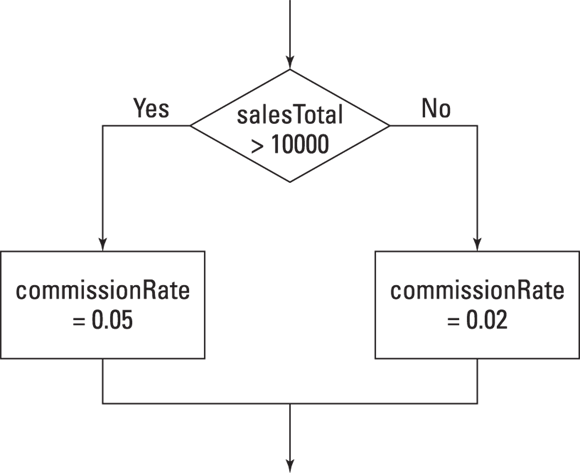

In this example, the commission rate is set to 2 percent if the sales total is less than or equal to $10,000. If the sales total is greater than $10,000, the commission rate is set to 5 percent. Figure 4-2 shows a flowchart for this if-else statement.

FIGURE 4-2: The flowchart for an if-else statement.

double commissionRate = 0.05;

if (salesTotal <= 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

You can use blocks for either or both of the statements in an if-else statement. Here’s an if-else statement in which both statements are blocks:

double commissionRate;

if (salesTotal <= 10000.0)

{

commissionRate = 0.02;

level1Count++;

}

else

{

commissionRate = 0.05;

level2Count++;

}

Nested if statements

The statement that goes in the if or else part of an if-else statement can be any kind of Java statement, including another if or if-else statement. This arrangement is called nesting, and an if or if-else statement that includes another if or if-else statement is called a nested if statement.

The general form of a nested if statement is this:

if (expression-1)

if (expression-2)

statement-1

else

statement-2

else

if (expression-3)

statement-3

else

statement-4

In this example, expression-1 is first to be evaluated. If it evaluates to true, expression-2 is evaluated. If that expression is true, statement-1 is executed; otherwise statement-2 is executed. But if expression-1 is false, expression-3 is evaluated. If expression-3 is true, statement-3 is executed; otherwise statement-4 is executed.

An if statement that’s contained within another if statement is called an inner if statement, and an if statement that contains another if statement is called an outer if statement. Thus, in the preceding example, the if statement that tests expression-1 is an outer if statement, and the if statements that test expression-2 and expression-3 are inner if statements.

Suppose that your company has two classes of sales representatives (Class 1 and Class 2) and that these reps get different commissions for sales below $10,000 and sales above $10,000, according to this table:

Sales |

Class 1 |

Class 2 |

$0 to $9,999 |

2% |

2.5% |

$10,000 and over |

4% |

5% |

You could implement this commission structure with a nested if statement:

if (salesClass == 1)

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.04;

else

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.025;

else

commissionRate = 0.05;

This example assumes that if the salesClass variable isn’t 1, it must be 2. If that’s not the case, you have to use an additional if statement for Class 2 sales reps:

if (salesClass == 1)

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.04;

else if (salesClass == 2)

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.025;

else

commissionRate = 0.05;

Notice that I place this extra if statement on the same line as the else keyword. That’s a common practice for a special form of nested if statements called else-if statements. You find more about this type of nesting in the next section.

You could just use a pair of separate if statements, of course, like this:

if (salesClass == 1)

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.04;

if (salesClass == 2)

if (salesTotal < 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.025;

else

commissionRate = 0.05;

The result is the same.

Note that you could also have implemented the commission structure by testing the sales total in the outer if statement and the sales representative’s class in the inner statements:

if (salesTotal < 10000)

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.04;

else

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.025;

else

commissionRate = 0.05;

The whole problem of knowing how else keywords are paired to if statements is called the dangling else problem. Whenever you use nested if statements with else clauses, you need to make sure you understand which else pairs to which if. Again, the rule is simple: Each else is matched with the most previous unmatched if.

Indentation is your friend here, but you must make sure that your indentation correctly matches the actual structure of your nested if and else statements.

But remember that Java doesn't care about your indentation. You can’t coax Java into pairing the if and else keywords differently by using indentation.

Suppose that Class 2 sales reps don’t get any commission, so the inner if statements in the preceding example don’t need else statements. You may be tempted to calculate the commission rate by using this code:

if (salesTotal < 10000)

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.025;

That won’t work. The indentation creates the impression that the else keyword is paired with the first if statement, but in reality, it’s paired with the second if statement. As a result, no sales commission rate is set for sales of $10,000 or more.

This problem has two solutions. The first, and preferred, solution is to use braces to clarify the structure:

if (salesTotal < 10000)

{

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.02;

}

else

{

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.025;

}

The other solution is to add an else statement that specifies an empty statement (a semicolon by itself) to the first inner if statement:

if (salesTotal < 10000)

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else ;

else

if (salesClass == 1)

commissionRate = 0.025;

The empty else statement is paired with the inner if statement, so the second else keyword is properly paired with the outer if statement.

else-if statements

A common pattern for nested if statements is to have a series of if-else statements with another if-else statement in each else part:

if (expression-1)

statement-1

else if (expression-2)

statement-2

else if (expression-3)

statement-3

These statements are sometimes called else-if statements, although that term is unofficial. Officially, all that’s going on is that the statement in the else part happens to be another if statement — so this statement is just a type of a nested if statement. It’s an especially useful form of nesting, however.

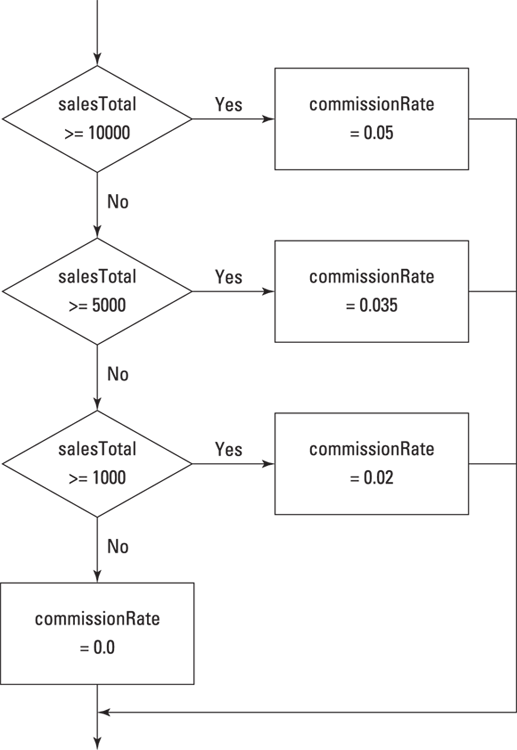

Suppose that you want to assign four commission rates based on the sales total, according to this table:

Sales |

Commission |

Over $10,000 |

5% |

$5,000 to $9,999 |

3.5% |

$1,000 to $4,999 |

2% |

Under $1,000 |

0% |

You can easily implement a series of else-if statements:

if (salesTotal >= 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.05;

else if (salesTotal >= 5000.0)

commissionRate = 0.035;

else if (salesTotal >= 1000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else

commissionRate = 0.0;

Figure 4-3 shows a flowchart for this sequence of else-if statements.

FIGURE 4-3: The flowchart for a sequence of else-if statements.

if (salesTotal > 0.0)

commissionRate = 0.0;

else if (salesTotal >= 1000.0)

commissionRate = 0.02;

else if (salesTotal >= 5000.0)

commissionRate = 0.035;

else if (salesTotal >= 10000.0)

commissionRate = 0.05;

Nice try, but this scenario won’t work. These if statements always set the commission rate to 0 percent because the boolean expression in the first if statement always tests true (assuming that the salesTotal isn’t zero or negative — and if it is, none of the other if statements matter). As a result, none of the other if statements are ever evaluated.

Using Mr. Spock’s Favorite Operators (Logical Ones, of Course)

A logical operator (sometimes called a Boolean operator) is an operator that returns a boolean result that’s based on the boolean result of one or two other expressions. Expressions that use logical operators are sometimes called compound expressions because the effect of the logical operators is to let you combine two or more condition tests into a single expression. Table 4-2 lists the logical operators.

The following sections describe these operators in excruciating detail.

Using the ! operator

The simplest of the logical operators is Not (!). Technically, it's a unary prefix operator, which means that you use it with one operand, and you code it immediately in front of that operand. (Technically, this operator is called the complement operator, not the Not operator. But in real life, most people call it Not. And many programmers call it bang.)

The Not operator reverses the value of a boolean expression. Thus, if the expression is true, Not changes it to false. If the expression is false, Not changes it to true.

TABLE 4-2 Logical Operators

Operator |

Name |

Type |

Description |

|

Not |

Unary |

Returns |

|

And |

Binary |

Returns |

|

Or |

Binary |

Returns |

|

Xor |

Binary |

Returns |

|

Conditional And |

Binary |

Same as |

|

Conditional Or |

Binary |

Same as |

Here’s an example:

!(i == 4)

This expression evaluates to true if i is any value other than 4. If i is 4, it evaluates to false. It works by first evaluating the expression (i == 4). Then it reverses the result of that evaluation.

i != 4

The result is the same. The Not operator can be applied to any expression that returns a true-false result, however, not just to an equality test.

! i == 4

Assuming that i is an integer variable, the compiler doesn’t allow this expression because it looks like you’re trying to apply the ! operator to the variable, not to the result of the comparison. A quick set of parentheses solves the problem:

!(i == 4)

Using the & and && operators

The & and && operators combine two boolean expressions and return true only if both expressions are true. This type of operation is called an And operation, because the first expression and the second expression must be true for the And operator to return true.

Suppose that the sales commission rate should be 2.5% if the sales class is 1 and the sales total is $10,000 or more. You could perform this test with two separate if statements (as I did earlier in this chapter), or you could combine the tests into one if statement:

if ((salesClass == 1) & (salesTotal >= 10000.0))

commissionRate = 0.025;

Here the expressions (salesClass == 1) and (salesTotal >= 10000.0) are evaluated separately. Then the & operator compares the results. If they’re both true, the & operator returns true. If one is false or both are false, the & operator returns false.

The && operator is similar to the & operator, but it leverages your knowledge of logic a bit more. Because both expressions compared by the & operator must be true for the entire expression to be true, there’s no reason to evaluate the second expression if the first one returns false. The & operator isn’t aware of this fact, so it blindly evaluates both expressions before determining the results. The && operator is smart enough to stop when it knows what the outcome is.

As a result, almost always use && instead of &. Here’s the preceding example, and this time it’s coded smartly with &&:

if ((salesClass == 1) && (salesTotal >= 10000.0))

commissionRate = 0.025;

Using the | and || operators

The | and || operators are called Or operators because they return true if the first expression is true or if the second expression is true. They also return true if both expressions are true. (You find the | symbol on your keyboard just above the Enter key.)

Suppose that sales representatives get no commission if total sales are less than $1,000 or if the sales class is 3. You could do that with two separate if statements:

if (salesTotal < 1000.0)

commissionRate = 0.0;

if (salesClass == 3)

commissionRate = 0.0;

With an Or operator, however, you can do the same thing with a compound condition:

if ((salesTotal < 1000.0) | (salesClass == 3))

commissionRate = 0.0;

To evaluate the expression for this if statement, Java first evaluates the expressions on either side of the | operator. Then, if at least one of these expressions is true, the whole expression is true. Otherwise the expression is false.

if ((salesTotal < 1000.0) || (salesClass == 3))

commissionRate = 0.0;

Like the Conditional And operator (&&), the Conditional Or operator stops evaluating as soon as it knows what the outcome is. Suppose that the sales total is $500. Then there’s no need to evaluate the second expression. Because the first expression evaluates to true and only one of the expressions needs to be true, Java can skip the second expression. If the sales total is $5,000, of course, the second expression must be evaluated.

As with the And operators, you should use the regular Or operator only if your program depends on some side effect of the second expression, such as work done by a method call.

Using the ^ operator

The ^ operator performs what in the world of logic is known as an Exclusive Or, commonly abbreviated as Xor. It returns true if one — and only one — of the two subexpressions is true. If both expressions are true, or if both expressions are false, the ^ operator returns false.

Put another way, the ^ operator returns true if the two subexpressions have different results. If they have the same result, it returns false.

Suppose that you’re writing software that controls your model railroad set, and you want to find out whether two switches are set in a dangerous position that might allow a collision. If the switches are represented by simple integer variables named switch1 and switch2, and 1 means the track is switched to the left and 2 means the track is switched to the right, you could easily test them like this:

if ( switch1 == switch2 )

System.out.println("Trouble! The switches are the same");

else

System.out.println("OK, the switches are different.");

Now, suppose that (for some reason) one of the switches is represented by an int variable where 1 means the switch goes to the left and any other value means the switch goes to the right — but the other switch is represented by an int variable where –1 means the switch goes to the left and any other value means the switch goes to the right. (Who knows — maybe the switches were made by different manufacturers.) You could use a compound condition like this:

if (((switch1==1)&&(switch2==-1)) || ((switch1!=1)&&(switch2!=-1)))

System.out.println("Trouble! The switches are the same");

else

System.out.println("OK, the switches are different.");

But an XOR operator could do the job with a simpler expression:

if ((switch1==1)^(switch2==-1))

System.out.println("OK, the switches are different.");

else

System.out.println("Trouble! The switches are the same");

Combining logical operators

You can combine simple boolean expressions to create more complicated expressions. For example:

if ((salesTotal<1000.0)||((salesTotal<5000.0)&&

(salesClass==1))||((salestotal < 10000.0)&&

(salesClass == 2)))

CommissionRate = 0.0;

Can you tell what the expression in this if statement does? It sets the commission to zero if any one of the following three conditions is true:

- The sales total is less than $1,000.

- The sales total is less than $5,000, and the sales class is 1.

- The sales total is less than $10,000, and the sales class is 2.

In many cases, you can clarify how an expression works just by indenting its pieces differently and spacing out its subexpressions. This version of the preceding if statement is a little easier to follow:

if (

(salesTotal < 1000.0)

|| ( (salesTotal < 5000.0) && (salesClass == 1) )

|| ( (salestotal < 10000.0) && (salesClass == 2) )

)

commissionRate = 0.0;

Figuring out exactly what this if statement does, however, is still tough. In many cases, the better thing to do is skip the complicated expression and code separate if statements:

if (salesTotal < 1000.0)

commissionRate = 0.0;

if ((salesTotal < 5000.0) && (salesClass == 1))

commissionRate = 0.0;

if ((salestotal < 10000.0) && (salesClass == 2))

commissionRate = 0.0;

if ( a==1 && b==2 || c==3 )

System.out.println("It's true!");

else

System.out.println("No it isn't!");

What do you suppose this if statement does if a is 5, b is 7, and c = 3? The answer is that the expression evaluates to true, and "It's true!" is printed. That’s because Java applies the operators from left to right. So the && operator is applied to a==1 (which is false) and b==2 (which is also false, but that doesn’t matter because this evaluation is skipped). Thus, the && operator returns false. Then the || operator is applied to that false result and the result of c==3, which is true. Thus the entire expression returns true.

if ( ( a==1 && b==2 ) || c==3 )

System.out.println("It's true!");

else

System.out.println("No it isn't!");

Here you can clearly see that the && operator is evaluated first.

Using the Conditional Operator

Java has a special operator called the conditional operator that’s designed to eliminate the need for if statements in certain situations. It’s a ternary operator, which means that it works with three operands. The general form for using the conditional operator is this:

boolean-expression ? expression-1 : expression-2

The boolean expression is evaluated first. If it evaluates to true, expression-1 is evaluated, and the result of this expression becomes the result of the whole expression. If the expression is false, expression-2 is evaluated, and its results are used instead.

Suppose that you want to assign a value of 0 to an integer variable named salesTier if total sales are less than $10,000 and a value of 1 if the sales are $10,000 or more. You could do that with this statement:

int tier = salesTotal > 10000.0 ? 1 : 0;

Although not required, a set of parentheses helps make this statement easier to follow:

int tier = (salesTotal > 10000.0) ? 1 : 0;

The following statement does the trick:

String msg = "You have " + appleCount + " apple"

+ ((appleCount>1) ? "s." : ".");

When Java encounters the ? operator, it evaluates the expression (appleCount>1). If true, it uses the first string (s.). If false, it uses the second string (".").

Comparing Strings

Comparing strings in Java takes a little extra care, because the == operator really doesn’t work the way it should. Suppose that you want to know whether a String variable named answer contains the value "Yes". You may be tempted to code an if statement like this:

if (answer == "Yes")

System.out.println("The answer is Yes.");

The correct way to test a string for a given value is to use the equals method of the String class:

if (answer.equals("Yes"))

System.out.println("The answer is Yes.");

This method actually compares the value of the string object referenced by the variable with the string you pass as a parameter and returns a Boolean result to indicate whether the strings have the same value.

The String class has another method, equalsIgnoreCase, that’s also useful for comparing strings. It compares strings but ignores case, which is especially useful when you’re testing string values entered by users. Suppose that you’re writing a program that ends only when the user enters the word end. You could use the equals method to test the string:

if (input.equals("end"))

// end the program

In this case, however, the user would have to enter end exactly. If the user enters End or END, the program won’t end. It’s better to code the if statement like this:

if (input.equalsIgnoreCase("end"))

// end the program

Then the user could end the program by entering the word end spelled with any variation of upper- and lowercase letters, including end, End, END, or even eNd.

You can find much more about working with strings in Book 4, Chapter 1. For now, just remember that to test for string equality in an if statement (or in one of the other control statements presented in the next chapter), you must use the equals or equalsIgnoreCase method instead of the == operator.

You must almost always enclose the expression that the

You must almost always enclose the expression that the  Most programmers don’t bother with the

Most programmers don’t bother with the