The Hope poster is kind of faded and a little dog-eared. 167

–BarackObama

There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos.

–Jim Hightower

Those of us who were bewitched by his eloquence on the campaign trail chose to ignore some disquieting aspects of his biography: that he had accomplished very little before he ran for president, having never run a business or a state; that he had a singularly unremarkable career as a law professor, publishing nothing in 12 years at the University of Chicago other than an autobiography; and that, before joining the United States Senate, he had voted “present” (instead of “yea” or “nay”) 130 times, sometimes dodging difficult issues.

–Drew Westen, “What Happened to Obama?”

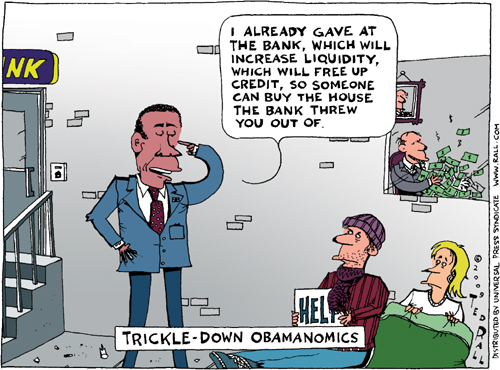

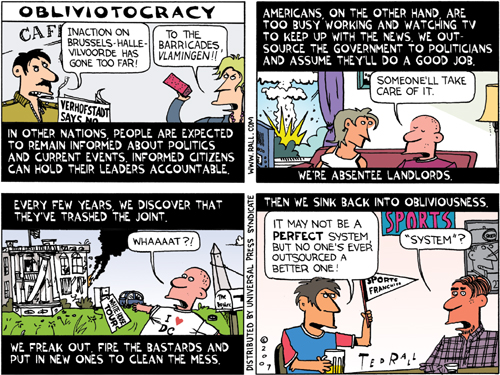

Two years into the Obama era, a substantial plurality of Americans finally accepted that electoral politics were useless. This was a big change, and one that gave us good reason to hope, though not the hope and change Obama presumably had in mind.

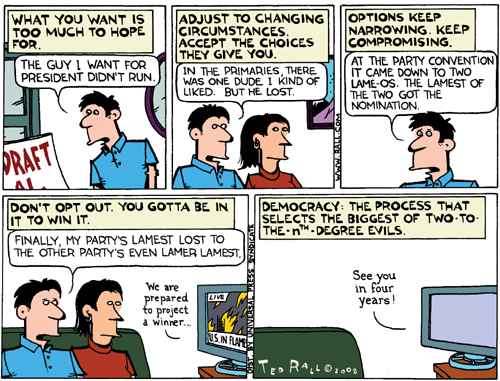

Until 2010, most Americans put significant faith into the system’s ability to respond to problems. It might take time, they thought, but eventually some solution would present itself and be enacted. Faith caused apathy and eventually Americans tuned out, turned over, and dropped out of the process, outsourcing their political destiny to whomever broadcast the snappiest debate lines and the most memorable commercials.

“The system” is like an onion, comprising numerous overlapping, interconnected and subsidiary systems: mainstream electoral politics, the Democratic-Republican duopoly, capitalism in general, the twenty-first century US variant of corporatist capitalism, the social underpinnings of these (schools, religion, family structure, popular culture), and so on.

Few Americans can see the system, much less understand how its subsidiary systems work together and manipulate them. But it’s not always necessary to know why or how a process functions in order to form a reasonable assessment about what is possible or impossible within it. Under this system, at this time, Obama was the most liberal, well-meaning, energetic, intelligent president we could get. Unfortunately he wasn’t energetic or smart enough to cope with the problems we faced. No matter how you look at it, there is no avoiding the conclusion that the system itself is the problem. If Obama–the best we could get–wasn’t up to the job, that was the fault of a system that wouldn’t allow anyone better to rise to the pinnacle of power.

Obama’s supporters claimed that he was highly competent but was being stymied by especially recalcitrant Congressional Republicans.168 If they are right, then the system is to blame for Obama’s inability to act. Whichever party is to blame, the Obama administration’s nonresponse on the economy, the BP spill, and America’s state of perpetual and unaffordable wars pushed the most traditionally alienated political factions into the streets. The far Right revolted first in 2010 as the Tea Party movement caught fire via the Internet and right-wing radio and television, rapidly evolving into a political force that swept the November elections. A year later, Occupy Wall Street would capture the energy and imagination of the long-dormant, alienated Left.

On February 19, 2009, a CNBC business news editor attacked Obama’s latest efforts to bail out the big Wall Street banks, complaining that a federal refinancing of bad mortgages represented moral hazard, that is, “promoting bad behavior.” A video of this broadcast, which included a call for a new Tea Party in which mortgage-backed derivatives would be dumped into the Chicago River, went viral.169

The Tea Party movement was born.

More an attitude than a traditional political party or movement, most Tea Partiers were conservative and/or libertarian, and their rallies seemed dominated by the so-called angry white (middle-aged) males of the 1990s. There were divergent strains of ideology and tactics. Many were members of the hard Right while others were barely disguised Republicans in period clothing. There were so-called AstroTurf Tea Party groups funded by the wealthy Koch brothers, and an isolationist wing inspired by the America First, small government, small military rhetoric of Ron Paul and Patrick Buchanan.

Matthew Continetti of the right-wing Weekly Standard said: “There is no single ‘Tea Party.’ The name is an umbrella that encompasses many different groups. Under this umbrella, you’ll find everyone from the woolly fringe to Ron Paul supporters, from Americans for Prosperity to religious conservatives, independents, and citizens who never have been active in politics before. The umbrella is gigantic.”170

Tea Partiers were angry about the state of the economy. Rather than blame Wall Street and the top 1 percent of the wealthiest Americans, however, Tea Partiers tended to blame poor and illegal immigrants for undercutting salaries and stealing American manufacturing jobs, as well as the “big government socialism” embodied by Obama’s healthcare reform act. They saw big government and high taxes as an impediment to business and an unnecessary strain at a time when un-and underemployed individuals could scarcely afford them.

Throughout 2010 support for the Tea Party ranged between 19 and 26 percent of American voters.

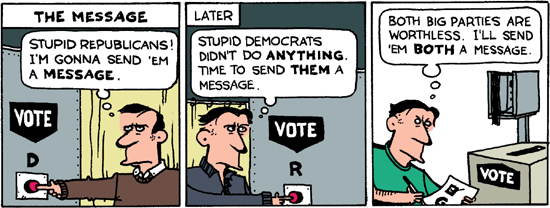

Republican Party officials tried (with some success) to divert the energy and enthusiasm of the Tea Party into the mainline GOP. Yet the Tea Party remained–and remains–a discrete entity. Most Tea Partiers distrust the Republicans as much as they fear the Democrats. Like the Occupiers, they see the system itself as the problem.

Ned Ryun, president of American Majority, a group that trains Tea Party activists, said: “I think we’re getting to the point where you can truly say we’re entering a post-party era. [Tea Partiers] aren’t going to be necessarily wed to a certain party–they want to see leadership that reflects their values first… They don’t care what party you’re in; they just want to know if you reflect their values–limited government, fixing the economy.”171

Right-wing congresswoman and 2012 Republican presidential candidate Michele Bachmann received permission to form an official Tea Party Caucus in the House of Representatives. It was official. The Tea Party mattered.

Lurking near the surface of Tea Partiers’ “take America back” rhetoric was a thinly disguised resentment that a black guy was president. Their tacit tolerance of intolerance spoke for itself. “Take America back” from whom? You know who. Not white CEOs.

Racism is only one facet of a far more sinister strand of Tea Party ideology.

The Tea Party was something the United States had never seen before, certainly not in such large numbers or as widespread: a proto-fascist movement.172

Robert O. Paxton, the Columbia University historian and author of The Anatomy of Fascism, denned fascism as “a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”173

Many Tea Party rants fit the mold. America, Tea Partiers complain, is falling behind. Like Hitler, they blame leftists and liberals for a “stab in the back”: treason on the home front. The trappings of hypernationalism–flags, bunting, and so on–are notably pervasive at Tea Party rallies, even by American standards. We see “collaboration with traditional elites”–Rush Limbaugh, congressmen, Republican Party bigwigs (including the most recent vice presidential nominee)–to an extent that is unprecedented in recent history.

Tea Partiers haven’t called for extralegal solutions to the problems they cite–but neither did the National Socialists prior to 1933. Then again, they’re not in power yet.

However, one major component is missing: aggressive militarism. Certainly most Tea Partiers support America’s wars and the troops who fight them, but Tea Partiers focus on domestic issues. Similarly, the Nazis didn’t make much of their aggressive intent until after they seized power.

Because it has no central leadership and because it’s easier to attract new members if you never say anything specific enough to turn anyone off, ideological vagueness is a defining characteristic of the Tea Party movement. Traditionally, ideological imprecision tends to increase as you move from left to right on the political spectrum.

On the Left, communists are specific to a fault (one reason why the Left is factionalized). Programs, five-year plans, and endless tracts are the (boring) order of the day under socialism. Moving right, bourgeois organizations such as the two major US political parties have platform planks and principles, but tend to be mushy and flexible. As we move to the far right, as under Hitler, ideas become grand, sweeping, meaningless slogans (take the nation back! death to the traitors!). What should be done is nominally whatever needs doing (i.e., whatever the leader orders).

Umberto Eco’s 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism” describes the cult of action for its own sake under fascist regimes and movements: “Action being beautiful in itself, it must be taken before, or without, reflection. Thinking is a form of emasculation.”174

Republican Senator John Cornyn defended Tea Partiers against charges of racism: “I think it’s slanderous to suggest the vast movement of citizens who have gotten off the couch and showed up at town hall meetings and Tea Party events, somehow to smear them with this label, there’s just no basis for it.”175 Notice Cornyn’s choice of words: Tea Par-tiers deserve praise for having gotten “off the couch.” They’ve shown up. That’s what matters! Never mind that they’re woefully uninformed and uneducated. Photo collages of Tea Partiers holding up misspelled signs became an Internet sensation. Cornyn’s statement demonstrated “effective collaboration with traditional elites” and another entry from Eco’s checklist: “Disagreement is treason.” Or slander. Whichever Ann Coulter book title floats your boat.

Eco also discusses fascism’s “appeal to a frustrated middle class, a class suffering from an economic crisis or feelings of political humiliation and frightened by the pressure of lower social groups.”176 Guard the borders! Deport the immigrants! Mexicans are stealing our jobs! The rage of the white middle-class males in the Tea Party is fully justified. Too bad it’s directed against their fellow victims.

If you got caught forging a mortgage application, you’d go to jail, but the law only goes after you if you’re a powerless individual citizen.

In one case in Florida, an employee of GMAC Mortgage admitted under oath that he personally forged ten thousand foreclosure affidavits. This low-level schlub was the tip of the tip of a massive iceberg, one of countless “robo-signers” whom voracious banks including GMAC, Bank of America, Citibank, and JPMorgan Chase hired in order to kick American families out of their homes as quickly as possible.

Ignoring state banking laws that require bank officers to review each foreclosure document to make sure all the facts are correct, banks instead hired low-wage “Burger King kids,” as Bank of America executives called them, to sign thousands of foreclosures they never looked at. Many were signed under someone else’s name.

Hundreds of thousands–maybe millions–of foreclosures were processed illegally by these huge banks gone wild. “Behind the question of improper foreclosure documentation lies a more important issue of whether lenders even have legal standing to foreclose because they lack the original mortgage note as required by law,” reports the New York Times.177 A 2010 study estimated this was the case for 40 percent of mortgages.178

One guy got evicted from his house in Florida despite the fact that his mortgage had been completely paid off years earlier. Meanwhile, thousands of people who purchased illegally foreclosed properties may not have legal title.

State and federal prosecutors investigated one of the biggest acts of wholesale fraud in the history of American business. Resorting to its by-now-familiar pattern, the Obama administration stood idly by and watched, then whipped together a low-ball class-action settlement in which people who lost their homes to an illegal robo-signing process would receive an average of $2,000.

It wasn’t a slap on the wrist. Houses for two grand each–that was the deal of the century!

When the no-deed scandal broke, the banks declared a temporary moratorium on foreclosures. Two weeks later, they declared the whole fuss a simple matter of paperwork and resumed their happy work of reducing millions of jobless Americans to homelessness. The president said nothing.

“There is not a single case where a foreclosure was made in error,” said Bank of America spokesman Dan Frahm (if that’s his real name). “The facts supporting the foreclosures are correct.”179

Bank of America evicted 102,000 families in November 2008, the month after the moratorium ended. How many of them would become homeless? Which kids would die from lack adequate medical care? How many distraught fathers would blow their brains out?

Adam Levitin, an associate law professor at Georgetown University, expressed doubt that the same banks that effectively rejected 99 percent of loan-modification applications by intentionally “losing” paperwork had suddenly become efficient. “The banks have dragged their feet and taken forever to do loan modifications, yet within less than two weeks they have managed to review hundreds of thousands of foreclosure cases,” he said. “It is simply not credible.”180

“These are banks going to court and committing fraud,” said Ira Rheingold of the National Association of Consumer Advocates. “For them to say this is a minor technical problem is mind-boggling.”181

Foreclosures needed to stop. Immediately. Forever.

They have always been terrible. It’s bad enough to fall on hard times, whether it’s due to a medical catastrophe or a job loss. But getting kicked out of your house forces you to couch surf or camp outside, struggling to survive day to day. And the whole family is affected–your spouse and children can be devastated. All of these things make it even harder to get back on your feet. (Foreclosures are also bad for your neighborhood: shuttered houses can reduce property values in the surrounding area.)

“We know how to prevent foreclosures,” Boston Federal Reserve Bank senior economist Paul Willen said in 2010. “We just need to be prepared to spend the money.” Willen saw “two possible solutions: Require banks to modify loans, basically imposing the cost on them; or pay banks to modify loans, imposing the cost on taxpayers.”182

Millions of American families have lost their homes to foreclosure since the crash of 2008. At this time 10.4 million additional households are in severe default on their mortgages–19 percent of all homes in the country–and that doesn’t count the millions of renters who are getting evicted because either they or their landlord is hurting.

The overwhelming majority of those facing foreclosure are people who got into trouble through no fault of their own. Most lost their job or suffered a medical catastrophe.

I feel their pain. Half of it, anyway.

I worked three days a week as an editor and talent scout for United Media, the newspaper syndication company, until I got laid off in April 2009. Just like that, half my income was gone. My bills, of course, remained the same, including my mortgage. I put down more than 50 percent of the purchase price when I bought my house in 2004. Refusing an adjustable-rate mortgage, I took out a vanilla thirty-year fixed-rate mortgage from Chase Home Finance LLC. My monthly payment of $2, 200 for the loan plus local property taxes was high but manageable in 2004. Then property taxes went up. Soon I was paying over $2, 700.I was still making payments, but only by borrowing from a home equity line of credit. I didn’t go into foreclosure, but the situation was unsustainable. The credit line wasn’t limitless and the more you borrow, the higher your payments. You can’t go on like that.

I decided to apply for a modification. I didn’t expect much. Thousands of people had reported getting the runaround. But I decided to try anyway. I’m good at paperwork, very detail oriented. And if they turned me down, it would make good research for my weekly column. There’s no better way to report on or to understand an event than to become part of it yourself.

Responding to political pressure to cut distressed homeowners a break, the big banks–including Chase–agreed to the Obama administration’s request to create a voluntary program to assist distressed homeowners. The result was a program called “Making Home Affordable.”

From Chase’s website: “No matter what your individual situation is, you may have options. Whether your want to stay in your home or sell it, we may be able to help” (emphasis mine).

Translation: “May” = “Won’t.”

As I can now attest from personal experience, Making Home Affordable is a scam. MHA gets cited by bank advertisements as evidence that they get it, that their “greed is good” days are over, that we don’t need to nationalize the sons of bitches and ship them off to reeducation labor camps.

In reality, MHA exists solely to provide banks like Chase with political cover. They deliberately give homeowners the runaround, endlessly dragging out the process so they can foreclose. As of the end of 2009, only 4 percent of applicants received any help. By June 2010, the vast majority of that “lucky” 4 percent had lost their homes anyway because the amount of relief they got was too small.

I was a banker in the eighties. It was detailed work. I often traveled to the former USSR where sloppy paperwork gives the police the right to shake you down for bribes and rob you blind. So I know how to navigate bureaucracy. I’m careful. Thorough. When, among other things–many, many other things–Chase asked me for copies of my bank statements, I knew to send the blank pages too.

I explained my situation to an officer at my local Chase branch. “As someone who recently lost a job and thus a substantial portion of your income,” she said, “you clearly qualify for Making Home Affordable. But you have to keep making your payments on time. Don’t fall behind or you’ll be disqualified.”

Clearly.

Chase Home Finance lists eligibility requirements for MHA; I easily fulfilled them. I was excited. To make sure I didn’t become the ten millionth American to lose his house since 2008, Chase would work to reduce my monthly payment. First, they would lengthen the repayment period. If that wasn’t enough help, they’d cut my interest rate. They might even reduce the principle.

I called in March. Happy day! After submitting 318 pages of records, most of them redundant, my application was finally complete. An actual living human being would be in touch shortly to tell me whether I’d been approved and, if so, how much of a break I’d get. I also got a letter. Application complete! Application complete! What were all those pissed-off Chase Home Finance customers on the Internet whining about? All you had to do was be thorough. And persistent.

April: no spring showers, but much melancholia and another letter. My application still wasn’t complete.

Again.

Had I sent in the same documents I’d already sent in four times and had confirmed three times? What about the bank statement that arrived between March and April? Where was that stuff? they asked. Kafka would have loved Chase.

I sent in the material a fifth time, along with a pissy cover note threatening to contact my congressman if they didn’t shape up.

Democracy works! One weeklater, on May 18, I received a rejection letter. The reason: I had not suffered any loss of income.

“If it is determined that you are not eligible for a Home Affordable Modification,” their website assures, “we’ll evaluate you for other workout options to keep you in your home or advise you of other foreclosure alternatives.”

Never heard from them.

As a former banker, I wondered how Chase could possibly say that I hadn’t lost income. Half isn’t anything? The system was rigged. Chase only asks for records that show income: W-2s, pay stubs, income statements, bank statements. They don’t look at your debt: credit cards, home equity lines of credit, other mortgages. Like most people whose income drops, my debts went up as I struggled to pay my bills. I offered to send that stuff, and they refused it. They probably would have “lost” it all anyway.

At this time I would like to express my unvarnished admiration for the ruthless cynicism that led the executives at Chase Home Finance to conceive of a fake lending branch entirely dedicated to increasing foreclosures, improving their public image, and driving distressed homeowners batshit crazy.

“The foreclosure-prevention program has had minimal impact,” John Taylor, chief executive of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, told the Associated Press. “It’s sad that they didn’t put the same amount of resources into helping families avoid foreclosure as they did helping banks.”183 After this experience, I would have volunteered for a firing squad of Chase executives. And I didn’t have to visit a Tea Party rally to find people as angry as me.

During the winter of 2010-11, I went on a book tour to promote The Anti-American Manifesto. I knew Americans were angry. People had lost faith in “their” government’s willingness or ability to address their needs and concerns. But their pessimism was deeper and broader than I thought. And their rage was burning white hot.

At the beginning of each event I asked attendees two questions. First, what is the worst problem that you face? Is it something the government could solve or at least mitigate? The top response was healthcare; either they or someone they knew couldn’t afford to see a doctor. Bear in mind that ObamaCare had already passed. Other answers included making college affordable and improving mass transit. Some were arcane: at the top of one man’s wish list was the metric system.

Second, what is the biggest problem the world faces today? Whether or not it personally affects you, what should be job one for the government?

Most people replied global warming or ecocide in general. Many complained about poverty and income inequality.

“Now think about your two top issues,” I asked them. “Do you think there’s any chance–not a high chance, not even a 50 percent chance, but a significant chance–that this system, our American capitalist system and the two-party political structure that supports it, will impact either one of those two issues?”

I reset for clarity. “Do you think you will see any improvement, on even one of those two problems, in your lifetime?” I asked for a show of hands. “Raise your hand if you have any faith, any optimism at all.”

Depending on the city, between 10 and 30 percent of my audiences raised their hands. Remember, these were Ted Rall readers, and few if any voted for John McCain, so when Obama–the man they did vote for–urged Americans of all political stripes “to stick with me, you can’t lose heart,” he was wasting his breath.184 Fifty-four percent of Americans expected the economy to remain the same or get worse in a year.185

“The biggest mistake we [Democrats] could make,” urged Obama as it became clear his party would suffer big losses in the midterm elections, “is to let impatience or frustration lead to apathy and indifference–because that guarantees the other side wins.”186

Impatience? There was nothing to be impatient about. Obama wasn’t moving too slowly. He wasn’t moving at all.

Other side? On issue after issue, Obama cut-and-pasted Bush’s Republican policies.

If you’re one of those 54 percent of Americans (or 70 to 90 percent of Ted Rall fans) who sees the government as unwilling and/or unable to alleviate your suffering, what should you do? If you don’t think the government will do anything for you, why not get rid of it?

“Republicans picked up at least 60 House seats in the biggest shift in power since Democrats gained 75 House seats in 1948,” Reuters reported the morning after the 2010 midterms.187

“It was the poor economy–not the wisdom of the Republicans’ ideas or the brilliance of their tactics–that assured they would retake control of the House,” said MarketWatch’s Rex Nutting. Sixty percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans told exit pollsters that the lack of jobs was their number-one issue. They blamed the incumbent Congress not for the situation, but rather for the Democrats’ seeming lack of concern, not to mention inaction. Obama never even proposed a jobs program.

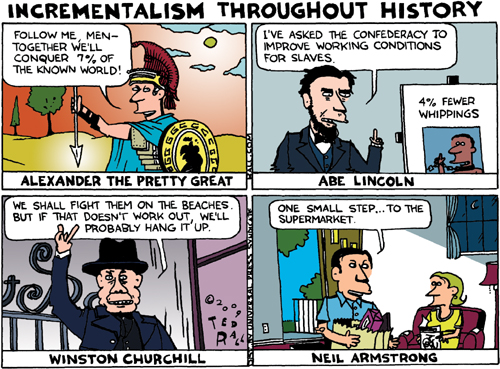

Chris Hedges put out a widely-talked-about book titled The Death of the Liberal Class. A better subject might have been the death of moderation, since that was the big political story of the year. And no one better embodies moderation than American liberals. They support income redistribution, but only through a slightly progressive income tax: not enough to make a difference, but plenty to make right-wingers spitting mad. They consistently vote for huge defense budgets and one war after another, yet let themselves get framed as wimps by Republicans whose rhetoric matches their bellicosity.

The smug and the complacent love moderation because it will not change the general scheme of things. ObamaCare: a perfect illustration of the perils of moderation passing itself off as “reasonable” compromise. The insurance companies get to soak even more Americans than usual–and charge those of us who are already in the system more. With healthcare, as with many other issues, an “extreme” (namely, a single-payer plan) would work much better than the “centrist,” “compromise” solution we were handed. Full-fledged socialized medicine would be better than free markets; merciless and inefficient as it is, for-profit healthcare beats a half-assed sop to insurance lobbyists.

Moderates are scared. They know their time is past. So they’re flailing. Loudly.

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg brought one thousand people together to create a militant moderate organization called No Labels. Like Jon Stewart’s Million Moderate March, No Labels is meant “not to create a new party, but to forge a third way within the existing parties, one that permits debate on issues in an atmosphere of civility and mutual respect,” say organizers. Yet another group, funded and run by a Wall Street hedge fund, the “centrist” Americans Elect is trying to get on the 2012 presidential ballot in all fifty states in order to run a nominee chosen by online balloting. (The popular vote can be overturned by a star chamber188 picked by the moneymen if the nominee turns out to be too, well, popular.)

I say bring on the extreme solutions because multi trillion-dollar deficits and endless war and mass die-offs of species and climate change are pretty fucking extreme; we’ve had enough half-assed compromises to deal with them.

There are many candidates for America’s Biggest Problem, so it’s tough to pick one. It could just as easily be education or immigration or a bunch of other issues. Still, as the foreclosures and layoffs piled up and the unemployment checks ran out for tens of millions, the issue that emerged as the one that would get the most attention was one that the media and political elites had been ignoring for over forty years.

Income inequality.

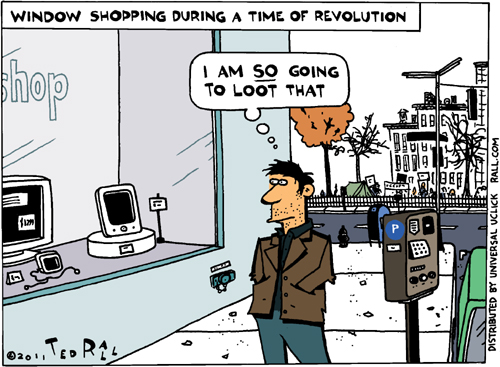

Watching millionaire bankers rake in record profits pushed that primal button that asks: Why does that bastard get to eat like a pig? Do I really have to sit here and starve?

Obviously not.

Not if I’m pissed off enough. Not if I stand up to the pigs.

Anger over building wealth and income inequality was the subliminal driving force behind the Tea Party. In 2011 that rage, overt now, became the catalyst and battle cry for the Occupy Wall Street movement. If Occupy had accomplished nothing other than putting income inequality at the center of the nation’s political discussion, it would still be a success.

You can’t talk about income inequality without eventually coming around to the conclusion that capitalism–to which inequality is innate–is the problem.

Putting capitalism on trial has interesting results. “I’m not about equality of result when it comes to income inequality. There is income inequality in America. There always has been and, hopefully, and I do say that, there always will be,” spat Rick Santorum on the campaign trail in February 2012.189 When you force capitalists and their defenders to speak up for it, they come off sounding like shits.

The land of the free is ground zero for economic injustice. “The United States is the rich country with the most skewed income distribution,” Eduardo Porter asserts in his upcoming book The Price of Everything: Solving the Mystery of Why We Pay What We Do. Porter continues:

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the average earnings of the richest 10 percent of Americans are 16 times those for the 10 percent at the bottom of the pile. That compares with a multiple of 8 in Britain and 5 in Sweden.

Not coincidentally, Americans are less economically mobile than people in other developed countries. There is a 42 percent chance that the son of an American man in the bottom fifth of the income distribution will be stuck in the same economic slot. The equivalent odds for a British man are 30 percent, and 25 percent for a Swede.190

For students of history and economics, this is shocking stuff. Europeans came to America in search of opportunity, for a better chance at a brighter future. How can it be that it’s easier to get ahead in Britain–famously ossified, rigidly class-defined Britain?

David Leonhardt of the New York Times agrees, in a discussion of income inequality in the US: “Income inequality, by many measures, is now greater than it has been since the 1920s.”191

According to Nicholas Kristof, also at the suddenly class-conscious Times, we live in a time of “polarizing inequality” during which “the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans possess a greater collective net worth than the bottom 90 percent.”192

Income inequality, it’s finally being acknowledged, is bad. Not just for us. For everybody. Even the rich are hurting themselves with their short-sighted greed.

Cornell economics professor Robert Frank analyzes the correlation between financial stress and social dislocation. “The counties with the biggest increases in inequality also reported the largest increases in divorce rates,” reports Frank.193 It’s also known that the children whose parents divorce are more likely to become a societal burden, committing crimes–including violent crimes–against everyone, including the wealthy (whose crimes are white collar).

Frank argues that our quality of life, across all income brackets, is suffering due to income inequality. For example, traffic jams are getting worse: “Families who are short on cash often try to make ends meet by moving to [places] where housing is cheaper–in many cases, farther from work. The [US] counties where long commute times had grown the most were again those with the largest increases in inequality.” Everyone sits in traffic, even millionaires.

The “middle-class squeeze,” Frank explains, pressures middle-income voters to vote against higher taxes that would support improvements in public infrastructure. We all pay: “Rich and poor alike endure crumbling roads, weak bridges, an unreliable rail system, and cargo containers that enter our ports without scrutiny. And many Americans live in the shadow of poorly maintained dams that could collapse at any moment.” Is it wrong to giggle at the thought of selfish millionaires being washed away by a flood?

Citing the work of the British epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, Nicolas Kristof blames just about every societal ill on the poverty created by high income inequality. Highlights among these ills: infant mortality, drug abuse, teen pregnancies, heart disease, even higher obesity among people who don’t eat more than others. This may be why Mississippi, Alabama, and West Virginia have the nation’s fattest people.194 (The hormone cortisol, released when humans are stressed, increases fat retention.)195

Porter notes that the income gap is also increasing among high earners. One study shows that in the 1970s, the top 10 percent of corporate executives earned twice as much as the average executive. Now they get four times more. “This has separated the megarich from the merely very rich,” he says.196

Income inequality is bad enough. Rising income inequality means things may get a lot worse. Not just for our waistlines, but for the system that has created the problem: corporate capitalism. “If only a very lucky few can aspire to a big reward,” Porter warns, “most workers are likely to conclude that it is not worth the effort to try.” That would lead to less legitimate innovation, fewer new businesses. The best and the brightest will conclude, as they have in post-Soviet Russia, that crime is the economic activity that pays best.

Until recently Americans tended to accept the argument that seven- and eight-digit salaries were justified by the value top executives added to the bottom line. Innovators in technology like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs earned billions in profits for shareholders. They were entrepreneurs, and they took risks that changed the world. They deserved to rake in the rewards.

People began reassessing this view after the 2008 collapse.

People are allowed to fail millions at a time, but corporations are deemed “too big to fail.” When big businesses go under, their executives get golden parachutes. The New York Times, bleeding tens of millions in losses per quarter, recently let go its underperforming CEO, Janet Robinson, easing her out the door with $4.5 million in “consulting” fees. Despite suffering a net loss of $7 billion in a single year, Hewlett-Packard paid Léo Apotheker a severance package worth $13.2 million, including moving fees to Europe and up to $300,000 to cover a loss on the sale of his house in California. Hardly the ideal of the deserving geek getting his or her due for the Big Idea That Paid Off.

Mitt Romney’s tax returns expose the sharp contrast between the capitalist ideal and corporatist reality. Romney received $45 million during 2010 and 2011. “The Romneys hold as much as a quarter of a billion dollars in assets, much of it derived from Mr. Romney’s time as founder and partner in Bain Capital, a private equity firm,” reported the New York Times.

Bain never created anything–no Bain products, no Bain innovations. It was a cash extraction machine that targeted profitable companies, saddled them with debt from leveraged buyouts, and then looted the smoldering ruins for the benefit of its top executives. Twenty-two percent of Romney’s targets were driven into bankruptcy. Thousands of workers lost their jobs. The world would have been a better place had Bain Capital–and Mitt Romney–never existed.

Romney deserves prison for creating this mayhem. Instead he made nearly $60,000 a day.

It doesn’t matter how hard you work, how smart you are, how good your ideas are. There’s no conversion factor between hard work and money. No one can “earn” $60,000 a day. It isn’t possible.

The public offering of Facebook stands to make founder Mark Zuck-erberg as much as $28 billion–more than the gross domestic products of Panama, Jordan, and a hundred other countries. By the way, Zucker-berg is already “worth” about $17 billion. He founded Facebook eight years ago. Does he deserve to earn $15,000,000 a day? That’s $6,000 a minute. Does anyone?

Income is a zero-sum game. Millions of people suffer–from home-lessness, hunger, lack of medical care, the bleakness of any foreseeable future for themselves or their children–so that one man can accumulate unimaginable wealth.

Facebook isn’t even a decently designed website.

So what is to be done?

This is where the income-inequality-is-bad brigade of the establishment liberal class falls flat on its face. All the problems they complain about–inequality, unequal justice in the courts, urban decay, pollution, disenfranchisement of minorities and the poor, the healthcare crisis-can be laid at the feet of capitalism, but liberals dare not overthrow the system. To do so they would risk ridicule in the establishment media and academic circles from which they draw their incomes. Trust me, I know. They walk right past the protestors who are screaming “Bernanke, tear down this class system!” shrug their shoulders, and hop in a cab back to their doorman co-ops on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Sure they look like wimps. But their checks clear.

Kristof’s prescription: “As we debate national policy in 2011–from the estate tax to unemployment insurance to early childhood education–let’s push to reduce the stunning levels of inequality in America today.”

Push? How? You can’t legislate this stuff. Not in a system that is so beholden to corporate interests that it can’t even take a break from treasury-looting to bribe angry voters with unemployment checks and mortgage refinances.

Porter’s solution: “Bankers’ pay could be structured to discourage wanton risk taking.” But bankers aren’t the only culprits. How would this restructuring take place? And who would force bankers to accept it?

Frank’s answer: “We should just agree that it’s a bad thing–and try to do something about it.”

Workers of the world, try to do something about uniting!

At least these liberals acknowledge that there’s a problem. Conservative defenders of capitalism pay lip service to the danger of economic unfairness but don’t take it seriously enough to float solutions worthy of a moment’s consideration.

The men quoted above know exactly what is causing this relentless increase in income inequality. Ruling elites have exploited globalization and technological advances to increase corporate profits through deregulation, union busting, and lobbying for federal subsidies and tax benefits. We’re witnessing what nineteenth-century communists predicted at the dawn of industrialization: capitalism’s natural tendency to aggregate wealth and power in the hands of fewer people and entities, culminating in monopolization so complete that the system finally collapses due to lack of consumer spending.

There is only one way to equalize income during the final crisis of capitalism: revolution.

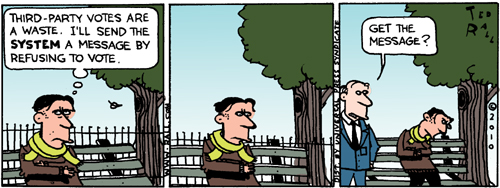

No matter how nicely we ask, why would the rich and powerful give up their wealth or their power? They won’t–unless it’s at gunpoint. Nothing short of revolution stands a chance of building a fair society. Not “pushing.” Not “restructuring.” If working within the Democratic Party and the Obama administration prove anything, it’s that reform within the system is no longer a viable strategy for progressives. Attempting to co-opt the Democrats led to four decades of failures and defeats. Occupy and street movements in general are the antidotes.

We’re way past “trying to do something about it.”

The sooner we start talking about revolution, the closer we’ll be to a no-bullshit solution to the social and political ills caused by income inequality.

Two state budget battles made headlines in 2011: California, where new/old governor Jerry Brown tried to close a $25 billion shortfall with a combination of draconian cuts in public services and a series of regressive tax increases, and Wisconsin, where right-winger Scott Walker argued that getting rid of public-service unions would eliminate the state’s $137 million deficit.

Neither party–neither Republicans nor Democrats–seriously tried to tax wealthy individuals and corporations.

Business shills whine that America’s corporate tax rate–35 percent–is one of the world’s highest. But that’s only in theory. Our real corporate rate–the rate companies actually pay after taking advantages of loopholes and deductions–is among the world’s lowest. According to the New York Times, Boeing paid a total tax rate of 4.5 percent over the last five years. (This includes federal, state, local, and foreign taxes.) Yahoo paid 7 percent. General Electric paid 14.3 percent. Southwest Airlines paid 6.3 percent. “G.E. is so good at avoiding taxes that some people consider its tax department to be the best in the world, even better than any law firm’s,” reports David Leonhardt. “One common strategy is maximizing the amount of profit that is officially earned in countries with low tax rates.”197

America’s low effective corporate tax rates have left big business swimming in cash while the country goes bust. As of March 2010, non-financial corporations in the United States had $26.2 trillion in assets; 7 percent of that was in cash. The national debt was $14.1 trillion.

It isn’t fair that millions are suffering for the benefit of a few. It is a prescription for political instability. The solution–abandoning a broken electoral system and taking to the streets–should have been obvious, but it took the people of Tunisia and Egypt to show us the way.

The British newspaper the Telegraph had this take on the Arab Spring revolts of early 2011: “Like in many other countries in the region, protesters in Egypt complain about surging prices, unemployment and the authorities’ reliance on heavy-handed security to keep dissenting voices quiet.”198

Sound familiar?

The first great wave of revolutions from 1789 through 1848 was a response to the decline of feudal agrarianism. (Like progressive historians, I don’t consider the 1775-1781 war of American independence to be a true revolution. It didn’t result in a radical reshuffling of classes and was little more than a bunch of rich tax cheats getting theirs.)

Throughout the nineteenth century, European elites saw the rise of industrial capitalism as a chance to stack the cards in their favor, paying slave wages for backbreaking work. Workers organized and formed a proletariat that rejected this lopsided arrangement. They rose up. They formed unions. By the mid-twentieth century, a rough equilibrium had been established between labor and management in the United States and other industrialized nations. Three generations of autoworkers earned enough to send their children to college.

Today, however, Detroit is a ghost town. Global capital trots across the world while the erstwhile workers who built transnational corporations are left behind. A recipe for high profits is usually one for political instability.

Our generation’s uprisings have their roots in the decline of industrial production that began sixty years ago. As in the early 1800s, the economic order has been reshuffled. Ports, factories, and the stores that serviced them have shut down. Thanks to globalization, industrial production has been deprofessionalized, shrunken, and outsourced to the impoverished Third World. The result, in Western countries, is a hollowed-out middle class, undermining the foundation of political stability in modern societies.

In the former First World, industry was supplanted by the “knowledge economy.” Rather than bringing the global economy in for a soft landing after the collapse of industrial capitalism by using the rising information sector to spread wealth, the ruling classes chose to do what they always do: they exploited the situation for short-term gain, grabbing whatever they could for themselves. During the seventies and eighties they broke the unions (one reason average family income has steadily declined since 1968). In the nineties and the first decade of the new millennium, they gouged consumers, whose credit cards are now maxed out.

Now the bill is due. They don’t want to pay. They want us to pay. But we can’t.

We won’t.

Old-school lefties say it can’t happen here. Not now. They say you can’t (or shouldn’t) have a revolution without first building a broad-based popular revolutionary movement.

“We are still in a time and place where we can and should be doing more to build popular movements that can liberate people’s consciousnesses and win reforms necessary to lay the foundation for a transformed society without it being soaked in blood,” Michael McGehee wrote in a Z Magazine review of The Anti-American Manifesto. The Manifesto, written in response to the economic crisis, called for Americans to rise up and overthrow the government. “All this talk about throwing bricks and Molotov cocktails is extremely premature and reckless,” complained McGehee.

That used to be true, but I think things have changed. Given the demoralized state of dissent in the United States since the 1960s, and the co-opting of radical activists by the cult of militant pacifism, it would be impossible to build such an organization in a reasonable amount of time. The Occupy phenomenon had to be ad hoc. The new New Left has to learn to drive as it heads down the street to who-knows-where.

I argued in my Manifesto that anyone who participates in the official Left as it exists today–MoveOn, Michael Moore, the Green Party-is inherently discredited in the current, rapidly radicalizing political environment. Old-fashioned liberals can’t really help, they can’t really fight–at least not if they want to maintain their pathetic positions, so they don’t really try. America’s future revolutionaries–the newly homeless, the illegally dispossessed, people bankrupted by the healthcare industry–can only view the impotent official Left with contempt.

Revolution will come. We’ve already seen the signs.

Day after day, month after month, the Great Recession has been grinding down tens of millions of families like the scene at the beginning of the first Terminator movie when the tank treads of monstrous automatons crush piles of human skulls. Most Americans have worn a brave face throughout the crisis, scraping together money for Christmas presents for their kids while they couch surf at their relatives’, members of the millions of “hidden homeless.” Expose a population to stress, however–particularly over an extended, seemingly endless period–and some individuals will snap. That’s what happened in February 2010, when fifty-three-year-old Andrew Stack flew his small plane into the Austin bureau of the Internal Revenue Service. “From relatives, friends and neighbors, a portrait emerged of Mr. Stack as a man pushed over the brink by retirement dreams deferred by a long series of financial setbacks,” reported the New York Times.

“I knew Joe had a hang-up with the I.R.S. on account of them breaking him, taking his savings away,” said Jack Cook, the stepfather of Mr. Stack’s wife, in a telephone interview from his home in Oklahoma. “And that’s undoubtedly the reason he flew the airplane against that building.”199

Collective Occupy-before-Occupy actions occurred as early as February 2009, when the Minneapolis-based Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign installed twelve families in foreclosed and/or abandoned homes and announced plans to expand into more. “First, we will try to utilize city services,” Cheri Honkala of the PPEHRC told the Minnesota Independent. “Generally, that’ll take five minutes because they don’t really exist… From there, they’ll go to a takeover house. As far as we’re concerned, there are thousands of empty houses. Not all of them are in that bad of shape and we’ll just borrow them until the city can tell us where these families will live.”200

Right-wingers were at it too. Throughout 2010 and 2011, members of the “sovereign citizen” movement–who say they’re not obligated to follow US or local law–took over dozens of foreclosed homes around Atlanta. Under a system in which a bank’s right to keep houses empty while millions sleep outside is sacrosanct, the authorities were upset: “They are one step away from becoming domestic terrorists,” said a FBI spokesman.201

As early as 2008, a popular blog by and for real estate agents recognized that the foreclosure epidemic was tearing at the nation’s social fabric:

There is also a growing trend of people squatting in their own homes after foreclosure. In some cases, these people have no place else to go when they lose their property, as the rental market in many areas is very difficult to get into. Others are simply taking advantage of a system that is totally overwhelmed right now due to the mortgage meltdown. These residents know that they can delay leaving the premises because the foreclosure process can take up to several months.

Regardless of the type of squatter, being homeless is a dark reality for many people, especially right now with the downturn of the economy. While laws must be upheld and property respected, we also need to keep in mind that these are people who are simply trying to survive. They are cold and need shelter, and right or wrong, they are using the vacant homes to get it. Those who are taking advantage of system ineptitudes will have to move eventually, and in the meantime, a dialogue needs to begin between members of the community, lending institutions, real estate professionals, and the government. Everyone in the community is affected by this problem, so we need to work together to find a solution that we can all live with.202

In South Florida, one of the epicenters of the foreclosure mess, one man even turned to seizing empty houses through the hoary legal precept of “adverse possession” and renting them out into a business.203

Now nearly forgotten, the highlight of the Occupy-before-Occupy period was the takeover of the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison. In February 2011, Republican Governor Scott Walker proposed a bill that would strip state workers of their collective bargaining rights. Tens of thousands of union members and their supporters demonstrated outside the capitol as legislators considered the proposal (which eventually passed). Thousands camped out inside the building, sleeping there overnight, hanging signs demanding that the governor be recalled. Though peaceful and–this being Wisconsin–polite, the action was notable for its militant tone. Hundreds of demonstrators shouted “Break down the door!” and “General strike!” during the state senate vote.

“It’s like Cairo has moved to Madison these days,” complained Wisconsin’s Republican congressman Paul Ryan.204

The Wisconsin protests petered out by June. Though not successful in restoring union rights, they galvanized the state’s Left and inspired activists around the country by showing that the occupation of public space was a useful tactic. Madison was proto-Occupy.

It wasn’t revolution and neither was Occupy Wall Street. Not even close. They were the first tentative steps down a road that can lead either to victory or to further repression of the hopes and dreams of the 99 percent of people who do the work and make things run.

When it does come, as it did in Tunisia and Egypt, revolutionary change in the United States will follow a spontaneous explosion of long pent-up social and economic forces. We will not need (or want) the old parties and progressive groups to lead us, which is good because they aren’t capable of creating revolution or midwifing it when it occurs. New formations will emerge from the chaos. They will create the new order.

Old-fashioned ideologies are obsolete. Left, Right, whoever must and will form alliances of convenience to overthrow the existing regime. The leftist critic Ernesto Aguilar is typical of those who take issue with me, complaining that “merging groups with different political goals around an agenda that does not speak openly to those goals, or worse, no politics at all, is bound for failure.” He wrote that before Occupy. I wonder what he thinks now.

The revolts in Tunisia and Egypt may well be destined for failure. Neither has succeeded in the ultimate goal of any real revolution–the overthrow of the ruling elites. The old guard remains in power. So far, however, these popular insurrections have played out exactly the way I predict it will, and must, here in the United States: set off by unpredictable events, formed by the people themselves, as the result of spontaneous passion rather than organized mobilization.

In Egypt, an ad hoc coalition composed of ideologically disparate groups (the Muslim Brotherhood, secular parties, independent intellectuals), coalesced around Mohamed ElBaradei. “Here you will see extremists, moderates, Christians, Muslims, all kinds of people. It is the first time that we are all together since the revolution of Saad Zaghloul,” a rebel named Naguib, referring to the leader of the 1919 revolution against the British, told Agence France-Presse.205

This is how it will go in Greece, Portugal, England, and–someday–here in the United States. There is no need to organize or plan. Scheming won’t make any difference. Just get ready to recognize revolution when it occurs, then drop what you’re doing and organize.

What will set off the real American Revolution? I don’t know. Nevertheless, the liberation of the long-oppressed peoples of the United States, and the citizens of nations victimized by its foreign policy, is inevitable.

Thank you, President Obama.

Christina-Taylor Green, age nine, was shot to death during a 2011 assassination attempt against Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. The murdered girl, said President Obama, had seen politics “through the eyes of a child, undimmed by the cynicism or vitriol that we adults all too often take for granted.”206

Obama didn’t venture to guess why Americans become alienated from mainline politics as they grow older. Perhaps he was too busy negotiating corrupt backroom deals to hazard a guess. Let me help: In a September 2010 interview with Rolling Stone, Obama claimed to have “accomplished 70 percent of the things that we said we were going to do–and by the way, I’ve got two years left to finish the rest of the list, at minimum.”207 It wasn’t close to true.208

Many Americans are registered to vote but rarely cast a ballot. (Usually whether or not a person is registered is the best predictor as to whether or not they actually vote.) A 2006 Pew Research survey found that 42 percent of these nonvoters said they were “bored by what goes on in Washington,” 14 percent were “angry at the government,” 32 percent said “issues in DC don’t affect me,” and 30 percent said “voting doesn’t change things.”209 How about all of the above?

“You’ve got to get out ahead of change,” Obama lectured. “You can’t be behind the curve.”210 Ah, the irony. The president was, of course, referring to the Arab Spring. During the previous few weeks there had been a new popular uprising every few days: Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Jordan, Bahrain, Libya.

And then, Wisconsin.

Revolutionary foment was on the march around the globe. Now that it had arrived in the American Midwest, however, Mr. Hopey Changey was nowhere to be found. What happened to “get out ahead of change?” What’s good for the Hosni wasn’t good for the Barry.

Deploying his customary technocratic aloofness in the service of the usual screw-the-workers narrative, President Obama sided with the union busters: “Everybody has to make some adjustments to the new fiscal realities,” he scolded the Madison occupiers.211

“Everybody,” naturally, did not include ultrarich dudes like our multimillionaire president. Obama, who declared a whopping $5.5 million in annual income for 2009 (the last year available), neither reduced his salary nor donated a penny of his $7.7 million fortune to the Treasury to help adjust to those “new fiscal realities.”

Hard times, doncha know, are for the little people. “We had [emphasis added] to impose a freeze on pay increases for federal workers in the next two years as part of my overall budget freeze,” Obama continued. “I think those kinds of adjustments are the right thing to do [in Wisconsin].”

Had to.

Interesting pair of words. They imply that there was no other choice.

There is always another choice. Tax. The. Rich. If they paid their fair share, there’d be no need to cut budgets.

Adjustments. How bloodless. For normal people, Herr President, losing 2 percent of one’s pay is not a mere adjustment. It hurts.

Meanwhile, Obama slapped a freeze on the paychecks of federal employees. Mere budgetary window dressing; it would save only $5 billion over two years. The Pentagon chucked as much down the Iraq and Afghanistan rat holes in a single week. Four hundredths of a percent of the deficit.

As the striking members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) learned in 1981, higher wages and better working conditions are for foreigners, not Americans. Ronald Reagan had nothing but praise for Solidarity in Poland, declaring that “the right to belong to a free trade union” was “one of the most elemental human rights.”212 At the same time he was defending Polish workers, Reagan fired all of America’s 11,345 striking air traffic controllers and ordered their union decertified.

All political systems are built on contradictions that eventually lead to their downfall. The United States relies on a whopping chasm between soaring rhetoric (freedom, democracy, individual rights) and brutish reality (preemptive war, support for dictators, torture, domestic spying)–a gap so wide and so glaring it is amazing anyone ever takes the propaganda seriously.

A report in the New York Times slathered on a rich quadruple serving of syrupy hypocrisy. The Obama administration asked the CIA to prepare a secret memo about the Arab Spring uprisings in the Middle East, specifically analyzing “how to balance American strategic interests and the desire to avert broader instability against the democratic demands of the protesters.”213

What exactly are those “strategic interests”? Business. Dictators cut sweetheart deals with big corporations that donate to the Democratic and the Republican parties. Democracy–real democracy, the kind people are fighting for in Bahrain and Madison–is incompatible with free-market capitalism. Democracy is what union members in Wisconsin–as well as those of us who don’t belong to unions but understand that we would be working hundred-hour weeks in deathtrap factories without them–saw clearly. The American Dream is a silly fantasy. A pipe dream. And most Americans are waking up.

Obama’s statement about the Arab autarchies is astonishingly indifferent to realities here at home. “I think that the thing that will actually achieve stability in that region is if young people, if ordinary folks, end up feeling that there are pathways for them to feed their families, get a decent job, get an education, aspire to a better life,” he said. “And the more steps these governments are taking to provide these avenues for mobility and opportunity, the more stable these countries are.”214

He could just as easily have been speaking about his own country. Young adults here are broke, jobless, and in debt, with no hope of improvement. According to a 2010 Bloomberg National poll, most American adults believe that their children will have worse lives than they do. In 2010, a staggering 80.3 percent of recent college graduates didn’t have a job, an increase of 29.3 percent from 2007.215

Hope? Change? Nowhere in sight.

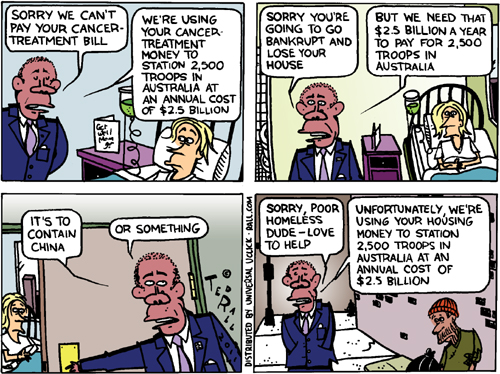

No money to extend unemployment benefits. No money to hire teachers. No money for new bridges or tunnels. No money for NASA, which means no more manned missions into space. No money to pay doctors, who heal the sick. No money to allow families who are down on their luck to stay in their homes.

Yet there is money.

Lots and lots of money.

They always find money for war. On March 19, 2011, US forces fired 110 cruise missiles at Libya on the first day of a war against the forty-two-year-old regime led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. Each cruise missile costs $755,000 to build plus $2.8 million to transport, maintain, and shoot. For people too young to remember Bosnia, this is what a violent, aggressive, militarist empire looks like under a Democratic president. Where Bush rushed, Obama moseys. No one believed ex-oil man Bush when he said he was out to get rid of the evil dictator of an oil-producing state, but Obama, former community organizer, gets a pass under identical circumstances. That weekend, also the eighth anniversary of the start of the Iraq quagmire, there were few protests against Obama’s optional Libya War, all of them poorly attended.

I spent the first weekend of Operation Falcon Freedom in New York at Leftforum, an annual gathering of anticapitalist intellectuals. “What do you think about Libya?” lefties asked each other. They were ambivalent.

This waffling on Libya was due in part to Obama’s deadpan (read: uncowboy-like) tone. Mostly, however, the tacit consent stemmed from televised images of ragtag anti-Gaddafi opposition forces getting strafed by Libyan air force jets. We Americans like underdogs, especially when they say they want democracy. And we love war, whether of the Bushian “smoke ‘em out” or the Obamian “more in sorrow than in anger” variety.

The United States and its allies destroyed Libya’s air force in order to tip the balance in the civil war in favor of anti-Gaddafi forces. A similar approach–aerial bombardment of Afghan government defenses–allowed Northern Alliance rebels to break through Taliban lines and enter Kabul in 2001. But who were these anti-Gaddafi forces? Rival tribes? Radical Islamists? Royalists? What are their ideological and religious motivations? No one knew. Now Gaddafi is dead and “our” guys are in charge in Tripoli, but we still don’t know who they are or what they want. And there are worrisome early warning signs of civil strife.

Obama loves circular logic. “Why strike only Libya, when other regimes murder their citizens too?” asked Chris Good in the Atlantic Monthly. “Obama’s answer seems to be: because the UN Security Council turned its attention toward Libya, and not other places.”216 But the UN reacted in response to a US request.

In addition to the optional carnage and cynical geopolitical manipulation, the war in Libya represented a new outrage, another example of a president who ran on the promise that he would restore the rule of law, choosing to brazenly ignore basic legal strictures.

Near the end of the Vietnam War, Congress overrode Richard Nixon’s veto and passed the War Powers Resolution, which requires the president to receive approval from Congress within sixty to ninety days of the commencement of “hostilities.” Partisan politics being as useless as they usually are, congressional Republicans were the only voices speaking out against Obama’s action in Libya, during which he simply blew off the deadline.

“Much rumbling has emanated from the US Congress on Libya–centered around technicalities around the War Powers Act [sic],” writes Pepe Escobar in Asia Times. “As the semantic contortions involved in the Libya tragedy have already gone way beyond newspeak, this means in practice US drones will keep joining NATO fighter jets in bombing civilians in Tripoli.”217

Of course, presidents of both parties have disputed the resolution’s constitutionality and/or have simply ignored it. As Daghlia Lithwick noted in Newsweek in 2008, the WPR has never stopped US presidents from bombing and shooting and whatnot.

“Congress is always too deferential, too credulous and too timid to check a strong president in wartime, and only ever speaks out after the war has become unpopular,” Lithwick wrote. “Congress will always offer up a tiny little authorization to use force, and stand by as that authorization swallows up several countries, many years and thousands of dead soldiers. Our war-powers problems lie not in the failure of checks and balances, but in the fact that Congress is invariably comfortable opposing wars only in hindsight.”218

Obama took a novel tack on Libya, stating that he believed the Resolution to be both constitutional and binding but not applicable to the bloodshed being unleashed upon Libya because it didn’t rise to the level of “hostilities.” Military operations against Libya, Obama’s lawyers stated, were under NATO control. They also claimed there were no US ground troops. Even if these claims were valid–most experts say they are not–they are transparently untrue. NATO is little more than a sock puppet for the United States. Both US soldiers and CIA operatives trained and armed the Benghazi-based rebels.

The people of Libya, like those of Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, and so on, suffered privation, mutilation, and death at the hands of NATO. To the thousands of Libyans who were killed or injured during the bombing campaign, legal niceties don’t matter. We cannot lose sight of that–and most of the world will not. It is only the Americans–characteristically oblivious about the places they wreck and the people they kill–who can’t find Libya on a map, much less worry about it.

Albeit secondarily, Obama’s disregard for the war powers law matters. It goes to the core of the nature of the American nation-state, the most heavily armed country on the planet and thus the most feared.

War is the riskiest endeavor a nation can undertake. It can lead to catastrophe (Germany at the end of World War II). It can end in not-defeat yet lead to collapse (the USSR in Afghanistan during the 1980s). It can ruin the economy (the United States in every war since Vietnam). Viewed as an unjustifiable act of aggression, it can create new enemies and corrode a nation’s moral standing internationally (the United States in Iraq).

Popular support is essential to victory. Thus, for political leaders there are two war-related principal reasons to make sure their populations support them: First, popular wars inspire sacrifice and recruits. Second, if and when there is a reversal of fortune, it is easier to ask for sustained effort.

Beyond practical considerations, any act as inherently significant as sending troops and bombs to attack a foreign power must involve the majority of the citizenry, and certainly all elected representatives. Otherwise it lacks even the window dressing of democracy.

Setting aside questions that ought not to be set aside–whether the US-NATO campaign against Gaddafi was winnable, benevolent, or consequential beyond the conflict zone–the outcome of the internal struggle over whether Obama has the right to unilaterally commit the armed forces has broad implications for the world.

Obama’s victory over the law establishes the precedent that a president need not consult with the legislative branch. The United States has undergone a scarcely noticed, final, undeniable transformation.

The bloom is off the tattered, skanky rose of American exceptionalism once and for all. A president can be legally elected yet act like, and thus effectively become, a dictator. Ironically, the International Criminal Court at The Hague issued a warrant for the Libyan ruler’s arrest for the killing, torture, and imprisonment of Libyan citizens. On the game of bloody mayhem, however, Gaddafi was a mere piker compared to his American counterpart. Obama killed thousands of Libyans (and Afghans and Iraqis) and controls an international gulag archipelago of secret prisons and torture camps. When will the ICC issue a warrant for Obama’s arrest?

Legally, the president of the United States has “not the power to command, but the power to persuade,” wrote political scientist Richard Neustadt.219 Theodore Roosevelt, the early twentieth-century president who spearheaded the transformation of the United States into a global empire, agreed. He dubbed the American presidency a “bully pulpit.” (By “bully,” he did not mean intimidating or aggressive but “terrific,” a meaning that has fallen out of popular usage.) The president is highly influential, but power resides with other government institutions.

The US Constitution is clear: only Congress has the right to declare war. This has happened only five times in American history (the most recent being in 1941, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt–famously declaring the day of the raid “a day that will live in infamy”–asked Congress to exercise its constitutional prerogative to authorize a formal state of war). Yet the United States has been one of the most bellicose nations on earth throughout its history. Rarely has a year passed without American military forces invading, occupying, shelling, bombing, or otherwise attacking a foreign country.

For all the admirable qualities of the American people–love of rock V roll, deep-fried food, hugely impractical cars, and ridiculous movies featuring explosions–Americans are not so smart. We are an easily confused lot.

The US Constitution was written in the late eighteenth century by men who had served as officials in the British colonial government. In England at the time, the term “commander in chief” was widely understood in the United States to be completely ceremonial. Early US presidents, who had been present at the constitutional conventions that created the framework of the new republic, understood and accepted that they had no right to commit soldiers to combat. The first president to do so, Thomas Jefferson, formally requested authorization from Congress in order to launch punitive raids against the Barbary States of North Africa, including the city-state of Tripoli. As time passed, however, presidents exploited war fever, fading memories, and ignorance to assert expanded executive power. Though never ratified by law, “commander in chief” came to imply something it had never meant originally: the unilateral right to declare war. Presidents often came to Congress for a rubber-stamp resolution of approval, but this was mere ceremony. Eventually they didn’t even bother.

“On the question of war power, I believe the Constitution is as clear as it is plain,” Joe Biden said on the floor of the US Senate in 1998. “To be sure, the [title of] Commander in Chief ensures that the President has the sole power to direct U.S. military forces in combat. But that power–except in very few limited circumstances–derives totally from congressional authority. It is not the power to move from a state of peace to a state of war. It is a power, once the state of war is in play, to command the forces, but not to change the state. Until that authority is granted, the President has no inherent power to send forces to war–except, as I said, in certain very limited circumstances, such as to repel sudden attacks or to protect the safety and security of Americans abroad.”220

Biden was right (at the time he was arguing against Bill Clinton’s undeclared war against Serbia), but it didn’t matter. In the United States, de facto trumps de jure. The US government is neither above nor beyond the law; it is outside. It is lawless.

While American bombs were smashing into Libya, an American commando team was ordered to invade Pakistani airspace, break into a house in Abbottabad, and murder Osama bin Laden, whom the United States accused of ordering the 9/11 attacks. The United States did not have permission from Pakistan. Indeed, Pakistani military forces attempted to respond with force. According to credible accounts, bin Laden was alive at the time of his capture before being executed by a member of Navy SEAL Team 6.

President Obama’s Sunday evening announcement, timed to fill Monday’s papers with a sickening orgy of gleeful triumph but little information, prompted bipartisan high fives and hoots all around. “U-S-A! U-S-A!” chanted a mob of drunken oafs in front of the White House. Blending the low satire of two Bush-era classic send-ups of a nation allergic to self-reflection–”Team America: World Police” and “Idiocracy”–they set the tone for a week of troop-praising, God-bless-America, frat-boy self-backslapping. “So that’s what success looks like,” wrote New York Times television critic Alessandra Stanley in the paper’s special ten-page “The Death of Bin Laden” pull-out section.221

Really? I would have thought that success looked like zero unemployment.

How many unemployment extension checks could have been paid with the resources devoted to assassinating one man? How many federal workers could have been hired?

“Bin Laden wanted to die as a martyr. In this sense, his wish was obliged,” noted Stephen Diamond in Psychology Today.222 Nothing was more important to bin Laden than to be seen as a brave soldier in an epic clash of civilizations. Claims that he hardly saw combat during the anti-Soviet resistance of the 1980s hurt him. The soft son of a Saudi billionaire and a former mama’s boy, bin Laden wanted to prove himself.

He did, courtesy of the SEALs. He went out in a blaze of glory, like Scarface. His status as a martyr, as a legend of jihad, is assured.

Yet another screwup for the United States, which fell into bin Lad-en’s trap after 9/11. To Al Qaeda and other Islamist groups, the United States and the West is enemy no. 2. Their biggest foes are pro-American Muslim dictators and autocrats, and the apathy and indifference among Muslims that allows them to remain in power. The martyrdom of bin Laden might contribute to a reversal of that indifference.

As with most actions carried out by small terrorist groups against enemies with superior manpower and weaponry, the operations attributed to bin Laden–the bombings of the US embassies in east Africa in 1998, the attack on the USS Cole in 2000, and 9/11–were intended to provoke the United States into overreacting, thus exposing it as the monster he said it was. The invasions of two Muslim countries, Guantánamo, torture, Abu Ghraib, the secret prisons, disappearances, and all the rest neatly fit into Osama Bin Laden’s narrative, proving his point more succinctly than a zillion fatwas faxed into Al Jazeera.

The bin Laden operation violated the sovereignty of a Muslim country, a constant complaint of radical jihadis. Armed commandos lawlessly invaded Pakistan. Infidel soldiers shot up a house and crashed a helicopter down the street from a military academy. Pakistanis routinely see American drones buzzing around overhead, invading their airspace with total impunity. American missiles blow up houses without being absolutely certain that they aren’t taking out non-combatants. Taking out bin Laden without Pakistani authorization is an act of war to which the country’s poverty permits no response. It’s yet another humiliation, another triumph of might over right.

In an echo of Bush’s selection of Guant ánamo as an extraterritorial not-US, yet not-foreign no-man’s-land, the Obama administration claimed that it buried bin Laden at sea. They justified this blasphemous form of burial because they couldn’t find a country to accept his body within the required twenty-four hours after death, and to avoid the possibility that his grave would become a shrine for Muslim extremists. However, bin Laden’s Wah-habi sect of Islam doesn’t allow burial at sea (or, for that matter, shrines).223

Few Americans were concerned about Muslim religious sensibilities. Countless editorial cartoons depicted sharks feasting on the carcass of the boogeyman of the Twin Towers. “Rot in Hell,” crowed the headline of the New York Daily News. “Justice has been done,” pundits and politicians claimed–a strange endorsement of extrajudicial assassination by a nation supposedly based on the rule of law.

“Triumphalism and unapologetic patriotism are in order,” wrote Eugene Robinson in the Washington Post. “We got the son of a bitch.”224

Classy.

When the powerful crush the weak, dancing around like a beefy hunk of steroids spiking the football at the touchdown line, they look small. Dumb, too. The worst thing that could have happened to Osama bin Laden would have been arrest followed by a fair trial.

When the president uses blatant sophistry in order to flout the law, when there is no entity powerful enough to stop him, citizens must choose between tacitly condoning lawlessness through inaction or acting to remove him and the system that allows him to function. Popular apathy prompts more aggression.

“After four decades of brutal dictatorship and eight months of deadly conflict, the Libyan people can now celebrate their freedom and the beginning of a new era of promise,” Obama crowed after the October 20, 2011, capture and death of Muammar Gaddafi.225 He congratulated the Libyan people on their liberation from a despot accused of terrible human rights violations, including the 1996 massacre of more than twelve hundred prison inmates.

The kudos were intended as much for the United States as they were for Libya’s victorious Transitional National Council. After all, the United States played a decisive role in Gaddafi’s death. First, President Obama put together the NATO coalition that served as the Benghazi-based rebels’ loaner air force. When the bombing campaign was announced in February, Gaddafi’s suppression of the human rights of protesting rebels was front and center: “The United States also strongly supports the universal rights of the Libyan people,” Obama said at that time. “That includes the rights of peaceful assembly, free speech, and the ability of the Libyan people to determine their own destiny. These are human rights. They are not negotiable. They must be respected in every country. And they cannot be denied through violence or suppression.”226 (No word on how the police firing rubber bullets at unarmed, peaceful protesters at the Occupy movement in Oakland, California, fits into that.)

And in the end, it was a Hellfire missile fired by a Predator drone plane controlled by the American CIA–in conjunction with an attack by a French fighter jet–that destroyed the convoy of cars Gaddafi and his entourage were traveling in to try to escape the siege of Sirte. This attack drove him into the famous drainage pipe and into the hands of his tormentors and executioners.

American officials and media reports were correct about Gaddafi’s human rights record: it was atrocious. They cautioned the incoming TNC to make human rights a priority: “The Libyan authorities should also continue living up to their commitments to respect human rights, begin a national reconciliation process, secure weapons and dangerous materials, and bring together armed groups under a unified civilian leadership,” Obama said.227 (No word on how Gaddafi’s execution or massacres of Gaddafi loyalists fits in to that, either.)