| 15 | In Perfect Shape The Platonic Solids |

The Greeks were very fond of symmetry. You can see it in their art, in their architecture, and in their mathematics. In plane geometry, a major area of Greek mathematics, the most symmetric polygons are the regular ones — polygons with all sides and all angles congruent. A regular triangle is one that is equilateral; a regular quadrilateral is a square.

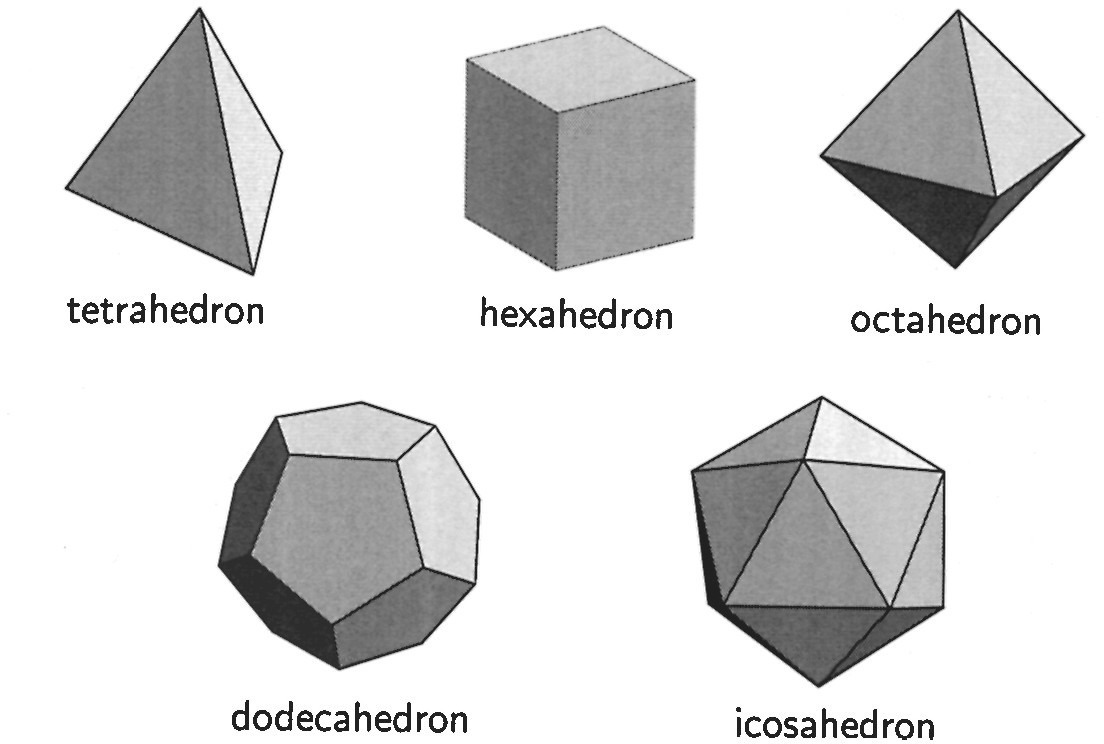

In three-dimensional space, a polyhedron is regular if all its faces are congruent regular polygons and all its vertices are similar. For example, a cube is a regular polyhedron; all its faces are squares of the same size and each vertex has four squares adjacent to it. It is a remarkable fact of geometry, proved as the final proposition of Euclid's Elements, that only a few convex regular polyhedra exist. (Contrast this with regular polygons, which can have any number of sides.) In fact, there are exactly five different types, as pictured in Display 1.

| tetrahedron | — | 4 faces (triangles) |

| hexahedron (cube) | — | 6 faces (squares) |

| octahedron | — | 8 faces (triangles) |

| dodecahedron | — | 12 faces (pentagons) |

| icosahedron | — | 20 faces (triangles) |

Display 1

The fact that there are only these five regular polyhedra may seem puzzling at first, but it is not hard to see why that must be so. Think of it this way:

•To form some sort of point or "peak," at least three polygonal faces must meet at any vertex of the polyhedron.

•Since the polyhedron is regular, the situation at any vertex is the same as at any other. Therefore, we only have to consider what happens at a typical vertex.

•In order to make a peak, the sum of all the face angles at the vertex must be less than 360°. (If they added up to exactly 360°, they would make a flat surface.)

•Since all the faces are congruent, the angle sum at a vertex must be divided up equally among them.

•Now let's look at the possible types of regular polygons that might be used as faces of these polyhedra:

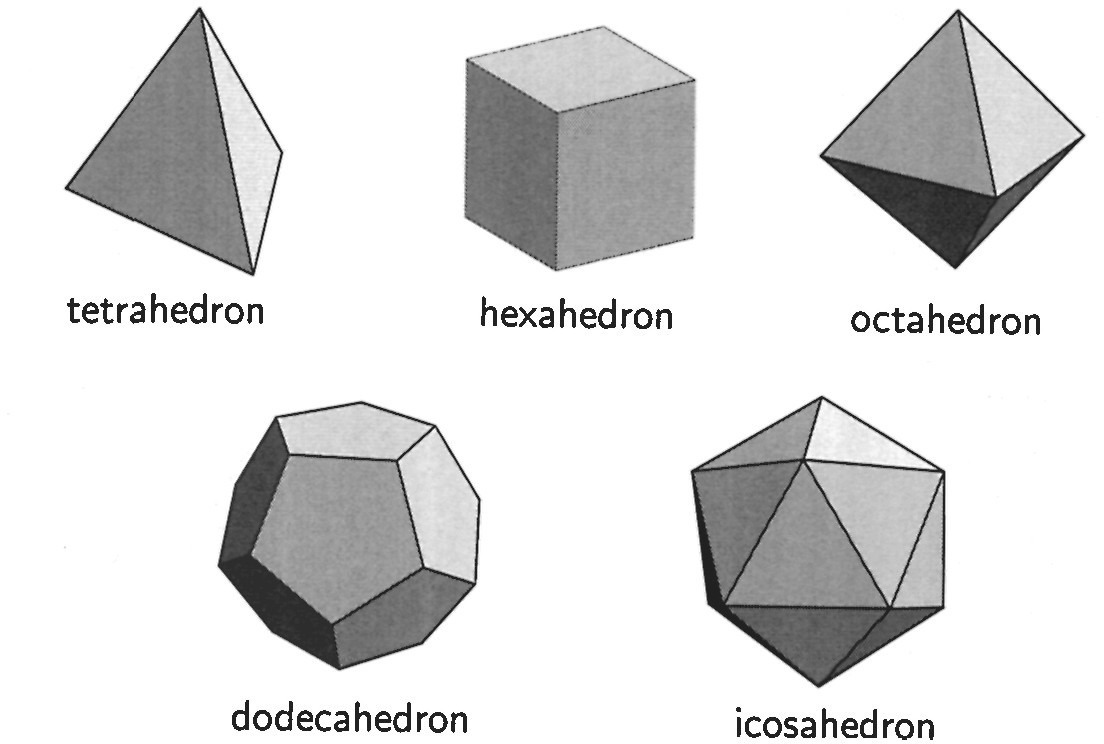

Triangles: Each angle of an equilateral triangle measures 60°. How many could you have together and still total less than 360°? 3 (180°), 4 (240°), or 5 (300°). (See Display 2.) That's all. Putting six together would give you a flat "peak," and more than that would be too large a total. These three possible cases give you the tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron.

Display 2

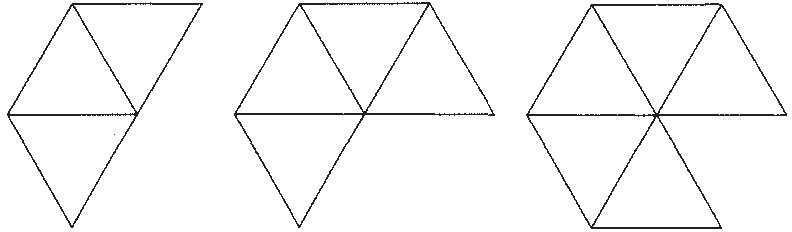

Squares: Each angle measures 90°. Three of them (totaling 270°) could meet at a vertex (of a cube), but four is too many. (See Display 3.)

Display 3

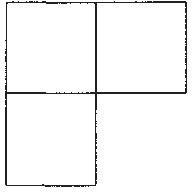

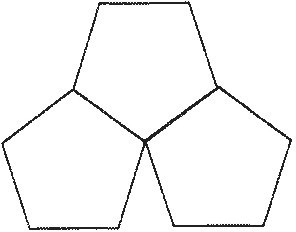

Pentagons: Each angle of a regular pentagon measures 108°. Three of them (totaling 324°) could meet at a vertex (of a dodecahedron), but four is too many. (See Display 4.)

Display 4

Hexagons: Each angle of a regular hexagon measures 120°. Three of them total 360°, which is too much! Thus, there is no regular polyhedron with hexagonal faces.

Other regular polygons: Each angle of a regular polygon with more than six sides must measure more than 120°. Three of them coming together at a point would total more than 360°. Therefore, there is no regular polyhedron with faces of any other kind.

The regularity of these shapes implies that each one can be inscribed in a sphere; that is, it can be placed inside a spherical shell in such a way that all its vertices are on the sphere. This was of great significance to the Pythagoreans, who connected four of the polyhedra with the four ''elements" of the physical world:

| fire | — | tetrahedron |

| earth | — | hexahedron (cube) |

| air | — | octahedron |

| water | — | icosahedron |

Plato discusses the connection between the elements and the polyhedra in one of his dialogues, the Timaeus, which tells stories about the creation of the cosmos. In it, the Creator is said to have used the tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron and cube as models for the fundamental particles of fire, air, water, and earth. The problem was what to do with the dodecahedron. (It had to have some significance!) Plato says that it served as a model for the whole universe, and so was a "fifth element," the fundamental essence of the universe. This is where we get the word "quintessence," which today means the best, purest, and most typical example of some quality, class of persons, or nonmaterial thing. Because of Plato's interest in them, these five polyhedra are known as "the Platonic Solids" or "the Platonic Bodies."

Can we get more solids if we relax the demands of regularity? Suppose we require that all the faces be regular polygons, but not necessarily all the same kind. So, for example, the faces could be either triangles or pentagons. We'll still require that all the triangles be congruent, that all the pentagons be congruent, and that all the vertices be similar.

The Greek mathematician Pappus tells us that Archimedes had considered this possibility and discovered that there were exactly 13 such solids. (Because of this, they are sometimes called the semi-regular polyhedra or the "Archimedean Solids.") Here's an example. Start with an icosahedron. It has triangular faces which come together, five at a time, in 12 vertices. Suppose we cut off each of these peaks. This will replace each of the 12 vertices by a new face, which will be a pentagon. If we do the cutting carefully, we can arrange that the surviving part of each of the 20 triangular faces is a regular hexagon. So we'll end up with a solid that has 20 hexagonal faces and 12 pentagonal ones. It is usually called the truncated icosahedron, and it actually exists in the "real world": it is the pattern on the cover of a traditional soccer ball.

In the Renaissance, mathematicians once again became fascinated by the regular and semi-regular solids. They learned about the five regular solids from Plato and Euclid, but most of them never read Pappus, so they had to rediscover the Archimedean solids. They did so slowly, with great excitement. This work culminated with Johannes Kepler (better known for his work in astronomy), who found all thirteen Archimedean solids and proved that there are no others.

Kepler, like Plato, tried to relate these beautifully symmetric solids to the real world. He once attempted to construct a theory of the solar system based on the Platonic Solids. He imagined that the orbit of each planet was in a large sphere. Then he said that if one inscribed a cube into the sphere of Saturn, the faces of the cube would be tangent to the sphere of Jupiter. Similarly, inscribing a tetrahedron in the sphere of Jupiter made the faces tangent to the sphere of Mars. And so on with the dodecahedron, the icosahedron, and the octahedron. Luckily, Kepler eventually gave up on this idea and went on to discover that the orbits of the planets are actually ellipses.

Plato's triangular theory of matter and Kepler's polyhedral theory of the solar system have not stood the test of time, but the Platonic solids can still be found in the earth's elements:

—the crystalline structures of lead ore and rock salt are hexahedral;

—fluorite forms octahedral crystals:

—garnet forms dodecahedral crystals:

—iron pyrite crystals come in all three of these forms;

—the basic crystalline form of the silicates (which form about 95% of the rocks in the Earth's crust) is the smallest of the regular triangular solids, the tetrahedron: and

—the sixty carbon atoms in the molecule known as the "buckyball" are arranged at the vertices of a truncated icosahedron.

For a Closer Look: See [32] for a full-length discussion of polyhedra that includes extensive historical information.