Chapter 21: Skeletal, Muscular, and Integumentary Systems

Lesson 21.1: Skeletal System

Lesson Objectives

- Identify the functions and structure of bones.

- Differentiate between the axial skeleton and appendicular skeleton.

- Distinguish between spongy bone and compact bone.

- Outline the process of osteogenesis (bone formation), and how bones grow.

- Classify bones based on their shape.

- Identify three types of joints that are in the body, and give an example of each.

- Identify three disorders that result from homeostatic imbalances of bones or the skeleton.

Introduction

How important is your skeleton? Can you imagine what you would look like without it?

You would be a wobbly pile of muscle and internal organs, maybe a little similar to the slug in Figure below. Not that you would really be able to see yourself anyway, due to the folds of skin that would droop over your eyes because of your lack of skull bones. You could push the skin out of the way, if you could only move your arms!

Figure 21.1

Banana slugs ( spp.), unlike you, can live just fine without a bony skeleton. They can do so because they are relatively small and their food source (vegetation) is plentiful and tends not to run away from them. Slugs move by causing a wave-like motion in their foot, (the ventral (bottom) area of the slug that is in contact with the ground). Slugs and other gastropods also live in environments very different to humans environments. Just think of how a bony skeleton would be of limited use to a slug whose lifetime is spent under a log munching on rotting leaf litter.

The Skeleton

Humans are vertebrates, which are animals that have a vertebral column, or backbone. Invertebrates, like the banana slug in Figure above, do not have a vertebral column, and use a different mechanism than vertebrates to move about. The sturdy internal framework of bones and cartilage that is found inside vertebrates, including humans, is called an endoskeleton. The adult human skeleton consists of approximately 206 bones, some of which are named in Figure below. Cartilage, another component of the skeleton can also be seen in Figure below. Cartilage is a type of dense connective tissue that is made of tough protein fibers. The function of cartilage in the adult skeleton is to provide smooth surfaces for the movement of bones at a joint. A ligament is a band of tough, fibrous tissue that connects bones together. Ligaments are not very elastic and some even prevent the movement of certain bones.

The skeletons of babies and children have many more bones and more cartilage than adults have. As a child grows, these “extra” bones, such as the bones of the skull (cranium), and the sacrum (tailbone) fuse together, and cartilage gradually hardens to become bone tissue.

Figure 21.2

The skeleton is the bone and cartilage scaffolding that supports the body, and allows it to move. Bones act as attachment points for the muscles and tendons that move the body. Bones are also important for protection. For example, your skull bones (cranium) protect your brain, and your ribcage protects your heart and lungs. Cartilage is the light-gray material that is found between some of the bones and also between the ribcage and sternum.

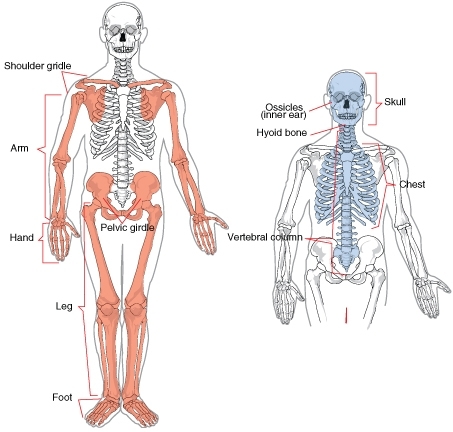

The bones of the skeleton can be grouped in two divisions: the axial skeleton and appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton includes the bones of the head, vertebral column, ribs and sternum, in the left portion of Figure below. There are 80 bones in the axial skeleton. The appendicular skeleton includes the bones of the limbs (arms and legs) along with the scapula and the pelvis, and is shown at right in Figure below. There are approximately 126 bones in the appendicular skeleton. Limbs are connected to the rest of the skeleton by collections of bones called girdles. The pectoral girdle consists of the clavicle (collar bone) and scapula (shoulder blade). The pelvic girdle consists of two pelvic bones (hipbones) that form the pelvic girdle. The vertebral column attaches to the top of the pelvis; the femur of each leg attaches to the bottom. The humerus is joined to the pectoral girdle at a joint and is held in place by muscles and ligaments.

Figure 21.3

The two divisions of the human skeleton. The bones of the axial skeleton are blue, and the bones of the appendicular skeleton are pink.

Function and Structure of Bones

Many people think of bones as dry, dead, and brittle, which is what you might think if you saw a preserved skeleton in a museum. The association of bones with death is illustrated by the sweets shown in Figure below. This is a common association because the calcium-rich bone tissue of a vertebrate is the last to decompose after the organism dies. However, the bones in your body are very much alive. They contain many tough protein fibers, are crisscrossed by blood vessels, and certain parts of your bones are metabolically active. Preserved laboratory skeletons are cleaned with chemicals that remove all organic matter from the bones, which leaves only the calcium-rich mineralized (hardened) bone tissue behind.

Figure 21.4

Sugar skulls made to celebrate Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead), a time (the 1 and 2 of November) during which the people of Mexico and some Latin American countries celebrate and honor the lives of the deceased, and celebrate the continuation of life.

Functions of Bones

As you read earlier in this lesson, your skeletal system is important for the proper functioning of your body. In addition to giving shape and form to the body, bones have many important functions.

The main functions of bones are:

- Structural Support of the Body: The skeleton supports the body against the pull of gravity. The large bones of the lower limbs support the trunk when standing.

- Protection of Internal Organs: The skeleton provides a rigid frame work that supports and protects the soft organs of the body. The fused bones of the cranium surround the brain to make it less vulnerable to injury. Vertebrae surround and protect the spinal cord and bones of the rib cage help protect the heart and lungs.

- Attachment of the Muscles: The skeleton provides attachment surfaces for muscles and tendons which together enable movement of the body.

- Movement of the Body: Bones work together with muscles as simple mechanical lever systems to produce body movement.

- Production of Blood Cells: The formation of blood cells takes place mostly in the interior (marrow) of certain types of bones.

- Storage of Minerals: Bones contain more calcium than any other organ in the form of calcium salts such as calcium phosphate. Calcium is released by the bones when blood levels of calcium drop too low. Phosphorus is also stored in bones.

Structure of Bones

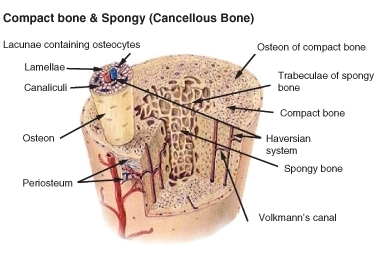

Although bones vary greatly in size and shape, they all have certain structural similarities. Bones are organs.Recall that organs are made up of two or more types of tissues. The two main types of bone tissue are compact bone and spongy bone. Compact bone makes up the dense outer layer of bones. Spongy bone is lighter and less dense than compact bone, and is found toward the center of the bone. Periosteum (from peri = around, osteo = bone),is the tough, shiny, white membrane that covers all surfaces of bones except at the joint surfaces. Periosteum is composed of a layer of fibrous connective tissue and a layer of bone forming cells. These structures can be seen in Figure below.

Figure 21.5

Structure of a typical bone. The components that make up bones can be seen here. Compact bone is the dense material that makes up the outer ring of the bone. Most bones of the limbs are long bones, including the bones of the fingers. The classification of long bone refers to the shape of the bone rather than to the size.

Figure 21.6

The internal structure of a bone. Both compact and spongy bone can be seen.

Compact Bone

Just below the periosteum is the hard layer of compact bone tissue. It is so called due to its high density, and it accounts for about 80% of the total bone mass of an adult skeleton. Compact bone is extremely hard, and is made up of many cylinder-shaped units called osteons, or Haversian systems. Osteons act like strong pillars within the bone to give the bone strength and allow it to bear the weight of the attached muscles and withstand the stresses of movement. As you can see in Figure above, osteons are made up of rings of calcium salts and collagen fibers, called bone matrix. Bone matrix is a mixture of calcium salts, such as calcium phosphate and calcium hydroxide, and collagen fibers (a type of protein) which form hollow tubes that look similar to the rings on a tree. Each of these matrix tubes is a lamella, which means “thin plate” (plural: lamellae). The calcium salts form crystals that give bones great strength, but the crystals do not bend easily, and tend to shatter if stressed. Collagen fibers are tough and flexible. All collagen fibers within a single lamella are lined up in the same direction, which gives each lamella great strength. Overall, the protein-calcium crystal combination in the matrix allows bones to bend and twist without breaking easily. The collagen fibers also act as a scaffold for the laying down of new calcium salts.

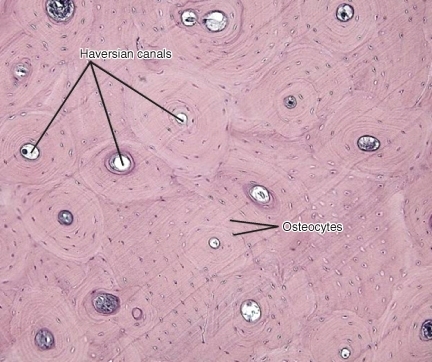

In the center of each osteon is a Haversian canal. The canal serves as a passageway for blood vessels and nerves. Within each osteon, many bone cells called osteocytes are located. Osteocytes are found in little pockets called lacunae that are sandwiched between layers of bone matrix. You can see lamellae and osteocytes in their lacunae in Figure 7b. Osteocytes are responsible for monitoring the protein and mineral content of the bone and they direct the release of calcium into the blood and the uptake up of calcium salts into the bone. Other bone cells, called osteoblasts secrete the organic content of matrix, and are responsible for the growth of new bone. Osteoblasts are found near the surface of bones. Osteoclasts are bone cells that remove calcium salts from bone matrix. These bone cells will be discussed in further detail later in this lesson. In the meantime, Table below describes some of the different structures and functions of bones.

The Structure of Bones

|

Function

|

Location

|

|

Osteons (also known as Haversian systems)

|

Act like pillars to give bone strength

|

Compact bone

|

|

Bone matrix

|

A mixture of calcium salts and collagen fibers which form hollow tubes that look similar to the rings on a tree

|

Compact bone, spongy bone

|

|

Lamella

|

Layers of bone matrix in which collagen fibers point in the opposite direction to the fibers of the lamellae to each side, offers great strength and flexibility

|

Are the “tree rings” of osteons

|

|

Lacunae

|

Location of osteocytes

|

Between lamellae of bone matrix

|

|

Osteocytes

|

Monitor the protein and mineral content of bone and direct the release of calcium into the blood; control the uptake up of calcium salts into the bone

|

Within lacunae of osteons

|

|

Osteoblasts

|

Bone-forming cell; secretes organic part of matrix (collagen)

|

Found near the surface of bones

|

|

Osteoclasts

|

Responsible for the breakdown of matrix and release of calcium salts into the blood.

|

Bone surfaces

|

|

Chondrocyte

|

Cartilage-forming cell

|

|

|

Periosteum

|

Contains pain receptors and is sensitive to pressure or stress; provides nourishment through a good the blood supply; provides an attachment for muscles and tendons

|

|

|

Collagen fibers

|

Tough protein fibers that give bones flexibility and prevent shattering.

|

|

|

Calcium salts

|

Form crystals that give bones great strength.

|

|

Figure 21.7

The location of Haversian canals and osteocytes in osteons of compact bone.

Spongy Bone

Spongy bone occurs at the ends of long bones and is less dense than compact bone. The term “spongy” refers only to the appearance of the bone, as spongy bone is quite strong. The lamellae of spongy bone form an open, porous network of bony branches, or beams called trabiculae, that give the bone strength and make the bone lighter. It also allows room for blood vessels and bone marrow. Spongy bone does not have osteons, instead nutrients reach the osteocytes of spongy bone by diffusion through tiny openings in the surface of the spongy bone. Spongy bone makes up the bulk of the interior of most bones, including the vertebrae.

Bone Marrow

Many bones also contain a soft connective tissue called bone marrow. There are two types of bone marrow: red marrow and yellow marrow. Red marrow produces red blood cells, platelets, and most of the white blood cells for the body. Yellow marrow produces white blood cells. The color of yellow marrow is due to the high number of fat cells it contains. Both types of bone marrow contain numerous blood vessels and capillaries. In newborns, bones contain only red marrow. As the child ages, red marrow is mostly replaced by yellow marrow. In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the flat bones of the skull, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones. It is also found between the spongy bone at the very top of the femur and the humerus.

Periosteum

The outer surfaces of bones—except where they make contact with other bones at joints—are covered by periosteum. Periosteum has a tough, external fibrous layer, and an internal layer that contains osteoblasts (the bone-growing cells). The periosteum is richly supplied with blood, lymph and nociceptors, which make it very sensitive to manipulation (recall that nociceptors are pain receptors that are also found in the skin and skeletal muscle). Periosteum provides nourishment to the bone through a rich blood supply. The periosteum is connected to the bone by strong collagen fibers called Sharpey's fibres, which extend into the outer lamellae of the compact bone.

Bone Shapes

The four main types of bones are long, short, flat, and irregular. The classification of a bone as being long, short, flat, or irregular is based on the shape of the bone rather than the size of the bone. For example, both small and large bones can be classified as long bones. There are also some bones that are embedded in tendons, these bones tend to be oval-shaped and are called sesamoid bones.

-

Long Bones: Bones that are longer than they are wide are called long bones. They consist of a long shaft with two bulky ends. Long bones are primarily made up of compact bone but may also have a large amount of spongy bone at both ends. Long bones include bones of the thigh (femur), leg (tibia and fibula), arm (humerus), forearm (ulna and radius), and fingers (phalanges). The classification refers to shape rather than the size.

-

Short Bones: Short bones are roughly cube-shaped, and have only a thin layer of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. The bones of the wrist (carpals) and ankle (tarsals) are short bones, as are the sesamoid bones (see below).

-

Sesamoid Bones: Sesamoid bones are embedded in tendons. Since they act to hold the tendon further away from the joint, the angle of the tendon is increased and thus the force of the muscle is increased. An example of a sesamoid bone is the patella (kneecap).

-

Flat Bones: Flat bones are thin and generally curved, with two parallel layers of compact bones sandwiching a layer of spongy bone. Most of the bones of the skull (cranium) are flat bones, as is the sternum (breastbone).

-

Irregular Bones: Irregular bones are bones that do not fit into the above categories. They consist of thin layers of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. As implied by the name, their shapes are irregular and complicated. The vertebrae and pelvis are irregular bones.

All bones have surface markings and characteristics that make a specific bone unique. There are holes, depressions, smooth facets, lines, projections and other markings. These usually represent passageways for vessels and nerves, points of articulation with other bones or points of attachment for tendons and ligaments.

Cellular Structure of Bone

When blood calcium levels decrease below normal, calcium is released from the bones so that there will be an adequate supply for metabolic needs. When blood calcium levels are increased, the excess calcium is stored in the bone matrix. The dynamic process of releasing and storing calcium goes on almost continuously, and is carried out by different bone cells.

There are several types of bone cells.

-

Osteoblasts are bone-forming cells which are located on the inner and outer surfaces of bones. They make a collagen-rich protein mixture (called osteoid), which mineralizes to become bone matrix. Osteoblasts are immature bone cells. Osteoblasts that become trapped in the bone matrix differentiate into osteocytes. The osteocytes stop making osteoid and instead direct the release of calcium from the bones and the uptake of calcium from the blood.

-

Osteocytes originate from osteoblasts which have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by bone matrix which they themselves produce. The spaces which they occupy are known as lacunae. Osteocytes are star-shaped, and they have many processes which reach out to meet osteoblasts probably for the purposes of communication. Their functions include matrix maintenance and calcium homeostasis. They are mature bone cells. Refer to Figure above for the location of osteocytes.

-

Osteoclasts are the cells responsible for bone resorption, which is the remodeling of bone to reduce its volume (see below). Osteoclasts are large cells with many nuclei, and are located on bone surfaces. They secrete acids which dissolve the calcium salts of the matrix, releasing them into the blood stream. This causes the calcium and phosphate concentration of the blood to increase. Osteoclasts constantly remove minerals from the bone, and osteoblasts constantly produce matrix that binds minerals into the bone, so both of these cells are important in calcium homeostasis.

Bone Cells and Calcium Homeostasis

Remodeling or bone turnover is the process of resorption of minerals followed by replacement by bone matrix which causes little overall change in the shape of the bone. This process occurs throughout a person's life. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts communicate with each other for this purpose. The purpose of remodeling is to regulate calcium homeostasis, repair micro-damaged bones (from everyday stress), and also to shape the skeleton during skeletal growth.

The process of bone resorption by the osteoclasts releases stored calcium into the systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, removing it from the bloodstream, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations.

Development of Bones

The terms osteogenesis and ossification are often used to indicate the process of bone formation. The skeleton begins to form early in fetal development. By the end of the eighth week after conception, the skeletal pattern is formed by cartilage and connective tissue membranes. At this point, ossification begins.

Early in fetal development, the skeleton is made of cartilage. Cartilage is a type of dense connective tissue that is composed of collagen fibers and/or elastin fibers, and cells called chondrocytes which are all set in a gel-like substance called matrix. Cartilage does not contain any blood vessels so nutrients diffuse through the matrix to the chondrocytes. Cartilage serves several functions, including providing a framework upon which bone deposition can begin and supplying smooth surfaces for the movement of bones at a joint, such as the cartilage shown in Figure below.

Figure 21.8

A micrograph of the structure of hyaline cartilage, the type of cartilage that is found in the fetal skeleton and at the ends of mature bones.

The bones of the body gradually form and harden throughout the remaining gestation period and for years after birth in a process called endochondrial ossification. However, not all parts of the fetal cartilage are replaced by bone, cartilage remains in many places in the body including the joints, the rib cage, the ear, the tip of the nose, the bronchial tubes and the little discs between the vertebrae.

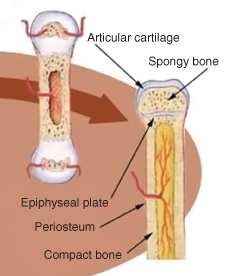

Endochondral Ossification

Endochondral ossification is the process of replacing cartilage with bony tissue, as shown in Figure below. Most of the bones of the skeleton are formed in this way. During the third month after conception, blood vessels form and grow into the cartilage, and transport osteoblasts and stem cells into the interior which change the cartilage into bone tissue. The osteoblasts form a bone collar of compact bone around the central shaft (diaphysis) of the bone. Osteoclasts remove material from the center of the bone, and form the central cavity of the long bones. Ossification continues from the center of the bone toward the ends of the bones.

The cartilage at the ends of long bones (the epiphyses) continues to grow so the developing bone increases in length. Later, usually after birth, secondary ossification centers form in the epiphyses, as shown in Figure below. Ossification in the epiphyses is similar to that in the center of the bone except that the spongy bone is kept instead of being broken down to form a cavity. When secondary ossification is complete, the cartilage is totally replaced by bone except in two areas. A region of cartilage remains over the surface of the epiphysis as articular cartilage and another area of cartilage remains inside the bone at either end. This area is called the epiphyseal plate or growth region.

Figure 21.9

The process of endochondrial ossification which happens when the skeleton is developing during fetal development, and in childhood.

When a bone develops from a fibrous membrane, the process is called intramembranous ossification. Intramembranous ossification usually happens in flat bones such as the cranial bones and the clavicles. During intramembranous ossification in the developing fetus, the future bones are first formed as connective tissue membranes. Osteoblasts migrate to the membranes and secrete osteoid, which becomes mineralized and forms bony matrix. When the osteoblasts are surrounded by matrix they are called osteocytes. Eventually, a bone collar of compact bone develops and marrow develops inside the bone.

Bone Elongation

An infant is born with zones of cartilage, called epiphyseal plates, shown in Figure below, between segments of bone to allow further growth of the bone. When the child reaches skeletal maturity (between the ages of 18 and 25 years), all of the cartilage in the plate is replaced by bone, which stops further growth.

Figure 21.10

Location of the epiphyseal plate in an immature long bone. The chondrocytes in the epiphyseal plate are very metabolically active, as they constantly reproduce by mitosis. As the older chondrocytes move away from the plate they are replaced by osteoblasts that mineralize this new area, and the bone lengthens.

Bones grow in length at the epiphyseal plate by a process that is similar to endochondral ossification. The chondrocytes (cartilage cells) in the region of the epiphyseal plate grow by mitosis and push older chondrocytes down toward the bone shaft (diaphysis). Eventually these chondrocytes age and die. Osteoblasts move into this region and replace the chondrocytes with bone matrix. This process lengthens the bone and continues throughout childhood and the adolescent years until the cartilage growth slows down and finally stops. When cartilage growth stops, usually in the early twenties, the epiphyseal plate completely ossifies so that only a thin epiphyseal line remains and the bones can no longer grow in length. Bone growth is under the influence of growth hormone from the anterior pituitary gland and sex hormones from the ovaries and testes.

Even though bones stop growing in length in early adulthood, they can continue to increase in thickness or diameter throughout life in response to stress from increased muscle activity or to weight-bearing exercise.

Joints

A joint (also called an articulation), is a point at which two or more bones make contact. They are constructed to allow movement and provide mechanical support for the body. Joints are a type of lever, which is a rigid object that is used to increase the mechanical force that can be applied to another object. This reduces the amount of energy that need to be spent in moving the body around. The articular surfaces of bones, which are the surfaces that meet at joints, are covered with a smooth layer of articular cartilage.

There are three types of joints: immovable, partly movable, and synovial. See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SOMFX_83sqk&feature=related for a brief overview of the types of joints.

-

Immovable Joint: At an immovable joint (or a fixed joint), bones are connected by dense connective tissue, which is usually collagen. Immovable joints, like those connecting the cranial bones, have edges that tightly interlock, and do not allow movement. The connective tissue at immovable joints serves to absorb shock that might otherwise break the bone.

-

Partly Movable Joints: At partly movable joints (or cartilaginous joints), bones are connected entirely by cartilage. Cartilaginous joints allow more movement between bones than a fibrous joint does, but much less than the highly mobile synovial joint. Examples of partly-movable joint include the ribs, the sternum and the vertebrae, shown in Figure below. Partly-movable joints also form the growth regions of immature long bones.

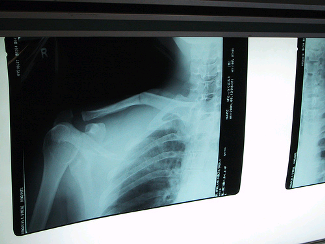

Figure 21.11

Illustration of an synovial disk, a cartilaginous joint. These partly-movable joints are found between the vertebrae. An X ray of the cervical (neck) vertebrae is at right.

-

Synovial joints: Synovial joints, also known as movable joints, are the most mobile joints of all. They are also the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints contain a space between the bones of the joint (the articulating bones), which is filled with synovial fluid. Synovial fluid is a thick, stringy fluid that has the consistency of egg albumin. The word "synovial" comes from the Latin word for "egg". The fluid reduces friction between the articular cartilage and other tissues in joints and lubricates and cushions them during movement. There are many different types of synovial joints, and many different examples. A synovial joint is shown in Figure below.

Figure 21.12

Diagram of a synovial joint. Sinovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body, and allow a wide range of motions. Think of how difficult walking would be if your knees and hips were only partly movable, like your spine.

The outer surface of the synovial joint contains ligaments that strengthen joints and holds bones in position. The inner surface (the synovial membrane) has cells producing synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and prevents the two cartilage caps on the bones from rubbing together. Some joints also have tendons which are bands of connective tissue that link muscles to bones. Bursae are small sacs filled with synovial fluid that reduce friction in the joint. The knee joint contains 13 bursae. Synovial joints can be classified by the degree of mobility they allow, as shown in Figure below.

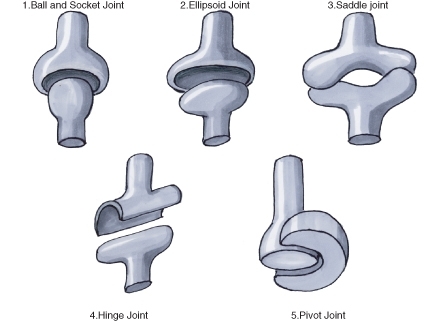

Figure 21.13

Types of Synovial joints. These fully-movable joints between bones allow a wide range of motions by the body. They also help reduce the amount of energy that needs to move the body.

In a ball and socket joint the ball-shaped surface of one bone fits into the cuplike depression of another. The ball-and-socket joint consists of one bone that is rounded and that fits within a cuplike bone. Examples of a ball and socket joint include the hip (Figure below) and shoulder.

In an ellipsoidal joint an ovoid articular surface, fits into an elliptical cavity in such a way as to permit of some back and forth movement, but not side-to-side motion. The wrist-joint and knee (Figure below), are examples of this type of joint.

Figure 21.14

Knee joint, an ellipsoid joint.

Figure 21.15

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint.

In a saddle joint the opposing bone surfaces are fit together like a person sitting in a saddle. The movements at a saddle joint are the same as in an ellipsoid joint. The best example of this form is the joint between the carpals and metacarpals of the thumb.

In the hinge joint, the articular surfaces fit together in such a way as to permit motion only in one plane, forward and backward, the extent of motion at the same time being considerable. An example of a hinge joint is the elbow.

The pivot joint is formed by a process that rotates within a ring, the ring being formed partly of bone, and partly of ligament. An example of a pivot joint is the joint between the radius and ulna that allows you to turn the palm of your hand up and down.

A gliding joint, also known as a plane joint, is a joint which allows one bone to slide over another, such as between the carpels of the fingers. Gliding joints are also found in your wrists and ankles.

Not all bones are interconnected directly: There are 6 bones in the middle ear called the ossicles (three on each side) that articulate only with each other. The hyoid bone which is located in the neck and serves as the point of attachment for the tongue, does not articulate with any other bones in the body, being supported by muscles and ligaments. The longest and heaviest bone in the body is the femur and the smallest is the stapes bone in the middle ear. In an adult, the skeleton makes up around 20% of the total body weight.

Homeostatic Imbalances of Bone

Despite their great strength, bones can fracture, or break. Fractures can occur at different places on a bone, and are usually due to excessive bending stress on the bone. Fractures can be complete in which the bone is completely broken, or incomplete in which the bone is cracked or chipped, but not broken all the way, as shown in Figure below. Immediately after a fracture, blood vessels that were torn leak blood into surrounding tissues and a mass of clotted blood, called a hematoma, forms. The area becomes swollen and sore. Within a few days capillaries begin to grow into the hematoma and white blood cells clean up the dead and dying cells. Fibroblasts and osteoblasts arrive and begin to rebuild the bone. Fibroblasts produce collagen fibers which span the area of the break and connect the ends of the broken bone together. Osteoblasts begin to form spongy bone, and chondroblasts form cartilage matrix. Later, the cartilage and spongy bone are replaced by a bony growth called a callus which forms about 3 to 4 weeks after the fracture, and continues until the break is firmly sealed 2 to 3 months later. Eventually the bony callus is replaced by spongy and compact bone, similar to the rest of the bone.

Figure 21.16

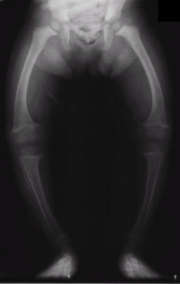

Rickets is a softening of the bones in children which potentially leads to fractures and deformity; bowing of the leg bones is shown in Figure below. Rickets is among the most frequent childhood diseases in many developing countries. The most common cause is a vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D is needed by the body to absorb calcium from foods and to form bones. However, lack of calcium in the diet may also cause rickets. Although it can occur in adults, most cases of rickets occur in children who suffer from severe malnutrition, which usually results from starvation during early childhood. Osteomalacia is the term used to describe a similar condition occurring in adults, generally due to a deficiency of vitamin D. Osteomalacia can result in bone pain, difficulty in putting weight on bones, and sometimes fractures.

Some studies show most people get enough Vitamin D through their food and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight. Vitamin D is produced by certain skin cells from a compound found inside the cells. The skin cells need UV light for this reaction to happen. However, eating foods to which vitamin D has been added or taking a dietary supplement pill is usually preferred to UV exposure, due to the increased risk of sun burn and skin cancer. Many countries have fortified certain foods such as milk, bread, and breakfast cereals with Vitamin D to help prevent deficiency.

Figure 21.17

An X ray image of a 2-year-old who shows the typical bowing of the femurs that occurs in rickets. Rickets causes poor bone mineralization, which results in the bones bending under the weight of the body.

Osteoporosis is a disease in which the breakdown of bone matrix by osteoclasts is greater than the building of bone matrix by osteoblasts. This results in bone mass that is greatly decreased, causing bones to become lighter and more porous. Bones are then more prone to breakage, especially the vertebrae and femurs. Compression fractures of the vertebrae and hip breaks, in which the top (or head) of the femur breaks are common, and can lead to further immobility, making the disease worse. Osteoporosis mostly occurs in older women and is linked to the decrease in production of sex hormones. However, poor nutrition, especially diets that are low in calcium and vitamin D, increase the risk of osteoporosis in later life. One of the easiest ways to prevent osteoporosis is to eat a healthful diet that has adequate calcium and vitamin D. For a brief animation of osteoporosis, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5uAXX5GvGrI.

Figure 21.18

Total replacement of hip joint. One of the leading reasons for hip replacement is osteoarthritis of the joint in which the cartilage around the top of the femur bone deteriorates over time, and causes the bones of the joint to grind painfully against each other. This can result in a narrowing of the space in the ball-and-socket joint structure, causing limited movement of the hip and constant pain in the hip joint.

Osteoarthritis is a condition in which wearing and breakdown of the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones leads to pain and stiffness in the joint. Decreased movement of the joint because of the pain may lead to muscles that are attached to the joint to become weaker, and ligaments may become looser. Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis. Some of the most common causes include old age, sport injuries to the joint, bone fractures, and overweight and obesity. Total hip replacement is a common treatment for osteoarthritis. An X ray image of a replacement hip joint is shown in Figure above. For a brief animation of osteoarthritis, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0dUSmaev5b0.

Lesson Summary

- The human skeleton is well adapted for the functions it must perform. Functions of bones include support, protection, movement, mineral storage, and formation of blood cells.

- The adult human skeleton usually consists of 206 named bones and these bones can be grouped in two divisions: axial skeleton and appendicular skeleton.

- There are two types of bone tissue: compact and spongy. Compact bone consists of closely packed osteons, or Haversian systems. Spongy bone consists of plates of bone, called trabeculae, around irregular spaces that contain red bone marrow.

- Osteogenesis is the process of bone formation. Three types of cells, osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, are involved in bone formation and remodeling.

- In intramembranous ossification, connective tissue membranes are replaced by bone. This process occurs in the flat bones of the skull. In endochondral ossification, bone tissue replaces hyaline cartilage models. Most bones are formed in this manner.

- Bones grow in length at the epiphyseal plate between the diaphysis and the epiphysis. When the epiphyseal plate completely ossifies, bones no longer increase in length.

- Bones may be classified as long, short, flat, or irregular. The diaphysis of a long bone is the central shaft. There is an epiphysis at each end of the diaphysis.

- There are three types of joints in terms of the amount of movement they allow: immovable, partly movable, and synovial joints (which are freely movable).

Review Questions

- Identify an example of a cell, a tissue, and an organ of the skeletal system.

- Identify the main bones of the axial skeleton.

- Identify the main bones of the appendicular skeleton.

- List four functions of bones and the skeleton.

- What is endochondrial ossification, and when does it occur?

- Name the three main types of joints, and identify a location in the body that is an example of that type of joint.

- Outline how a bone fracture is repaired.

- What is the purpose of Haversian canals?

- Leukemia is a type of cancer that affects bone. It is a disease in which there is an overproduction of immature white blood cells. Identify the area of bone that is affected by leukemia.

Further Reading / Supplemental Links

Vocabulary

-

appendicular skeleton

-

The portion of the human skeleton that includes the bones of the limbs, scapula and the pelvis.

-

axial skeleton

-

The portion of the human skeleton that includes the bones of the head, vertebral column, ribs and sternum.

-

bone marrow

-

A soft, connective tissue found in the interior bones. Red bone marrow produces red blood cells and white blood cells are produced by yellow bone marrow.

-

bone matrix

-

A mixture of calcium salts, such as calcium phosphate and calcium hydroxide, and collagen fibers (a type of protein), which form hollow tubes that look similar to the rings on a tree.

-

cartilage

-

Dense connective tissue that is made of tough protein fibers. The function of cartilage in the adult skeleton is to provide smooth surfaces for the movement of bones at a joint.

-

compact bone

-

A type of tissue that makes up the dense outer layer of bones.

-

endochondrial ossification

-

The process of replacing cartilage with bony tissue, occurs during the gestation period and for years after birth.

-

endoskeleton

-

The sturdy internal framework of bones and cartilage that is found inside vertebrates.

-

epiphyseal plate

-

Also known as the growth plate, the area of cartilage at the end of long bones, responsible for elongation of the bone.

-

fracture

-

A break in a bone.

-

haversian canal

-

Located in the center of each osteon, serves as a passageway for blood vessels and nerves.

-

intramembranous ossification

-

The process of bone tissue developing from a fibrous membrane, usually occurs in flat bones, such as the clavicle.

-

joint

-

A point at which two or more bones make contact; also called an articulation.

-

ligament

-

A band of tough, fibrous tissue that connects a bone to another bone.

-

osteoarthritis

-

A condition in which wearing and breakdown of the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones leads to pain and stiffness in the joint.

-

osteoblast

-

A type of bone cell that secretes the organic content of bone matrix, and is responsible for the growth of new bone.

-

osteoclast

-

A type of bone cell that removes calcium salts from bone matrix.

-

osteocyte

-

A type of bone cell that is responsible for monitoring the protein and mineral content of the bone, directing the release of calcium into the blood, and directing the uptake up of calcium salts into the bone.

-

osteons

-

Cylinder-shaped units that act like strong pillars within compact bone to give strength, allow the bone to bear the weight of the attached muscles, and withstand the stresses of movement.

-

osteoporosis

-

A disease in which the breakdown of bone matrix by osteoclasts is greater than the building of bone matrix by osteoblasts.

-

periosteum

-

The tough, shiny, white membrane that covers all surfaces of bones except at the joint surfaces.

-

rickets

-

A common disease among children in developing countries; symptoms include soft bones that are prone to fractures.

-

spongy bone

-

A type of tissue that is less dense than compact bone, and is found toward the center of the bone.

-

synovial fluid

-

A thick fluid that reduces friction between the articular cartilage and other tissues in synovial (moveable) joints and lubricates and cushions them during movement.

Points to Consider

- Consider how what you eat today can influence your chance of developing osteoporosis later in life.

- Forensic pathologists can estimate the age of a deceased person even if only their skeleton remains. Consider how this is possible.

Lesson 21.2: Muscular System

Lesson Objectives

- Outline the major role of the muscular system.

- Relate muscle fibers, fascicles, and muscles to the muscular system.

- Explain how muscle fibers contract.

- Examine the role of ATP and calcium in muscle contraction.

- Outline how muscles move bones.

- Explain how muscles respond to aerobic and anaerobic exercise.

Introduction

The muscular system is the biological system of humans that allows them to move. The muscular system, in vertebrates, is controlled through the nervous system. Much of your muscle movement occurs without your conscious control and is necessary for your survival. The contraction of your heart and peristalsis, the intestinal movements that pushes food through your digestive system, are examples of involuntary muscle movements. Involuntary muscle movement is controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Voluntary muscle contraction is used to move the body and can be finely controlled, such as the pincer-type movement of the fingers that is needed to pick up chess pieces, or the gross movements of legs arm, and the torso that are needed in skating, shown in Figure below. Voluntary muscle movement is controlled by the somatic nervous system.

Figure 21.19

You need muscles to play chess. Playing chess requires fine motor movement, but not a lot of gross muscle movements. Skating on the other hand, requires a lot of gross muscle movement of the limbs and the entire body.

Muscle Tissues

Each muscle in the body is composed of specialized structures called muscle fibers. Muscle fibers are long, thin cells that have a special talent that other cells do not have—they are able to contract. Muscles, where attached to bones or internal organs and blood vessels, are responsible for movement. Nearly all movement in the body is the result of muscle contraction. Exceptions to this are the action of cilia, the flagellum on sperm cells, and the amoeboid movement of some white blood cells.

Three types of muscle tissue are in the body: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac.

-

Skeletal muscle is usually attached to the skeleton. Skeletal muscles are used to move the body. They generally contract voluntarily (controlled by the somatic nervous system), although they can also contract involuntarily through reflexes.

-

Smooth muscle is found within the walls of organs and structures such as the esophagus, stomach, intestines, bronchi, uterus, urethra, bladder, and blood vessels. Unlike skeletal muscle, smooth muscle is involuntary muscle which means it not under your conscious control.

-

Cardiac muscle is also an involuntary muscle but is a specialized kind of muscle found only within the heart.

Cardiac and skeletal muscles are striated, in that they contain highly-regular arrangements of bundles of protein fibers that give them a “striped” appearance. Smooth muscle does not have such bundles of fibers, and is non-striated. While skeletal muscles are arranged in regular, parallel bundles, cardiac muscle fibers connect at branching, irregular angles. Skeletal muscle contracts and relaxes in short, intense bursts, whereas cardiac muscle contracts constantly for 70 to 80 years (an average life span), or even longer.

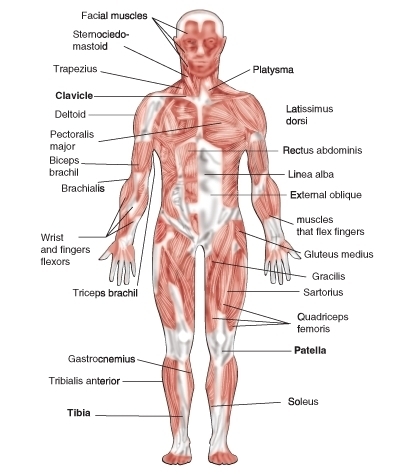

Figure 21.20

Frontal view of the major skeletal muscles. You would not see smooth and cardiac muscles included in diagrams of the muscular system because such diagrams usually show only the muscles that move the body (skeletal muscles).

Skeletal Muscle

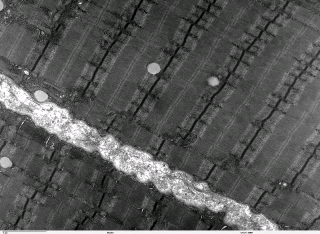

Skeletal muscle, which is attached to bone, is responsible for body movements and body posture. There are approximately 639 skeletal muscles in the human body, some of which are shown in Figure above. These muscles are under conscious, or voluntary, control. The basic units of skeletal muscle are muscle cells that have many nuclei. These muscle cells also contain light and dark stripes called striations, which are shown in Figure below. The striations are a result of the orientation of the contractile proteins inside the cells. Skeletal muscle is therefore called striated muscle. Each muscle cell acts independently of its neighboring muscle cells. On average, adult males are made up of 40 to 50 percent skeletal muscle tissue and an adult female is made up of 30 to 40 percent skeletal muscle tissue.

Figure 21.21

Micrograph of skeletal muscle. The stripy appearance of skeletal muscle tissue is due to long protein filaments that run the length of the fibers.

Smooth Muscle

Smooth muscle is found in the walls of the hollow internal organs such as blood vessels, the intestinal tract, urinary bladder, and uterus. It is under control of the autonomic nervous system. This means that smooth muscle cannot be controlled consciously, so it is also called involuntarily muscle. Smooth muscle cells do not have striations, and so smooth muscle is also called non-striated muscle. Smooth muscle cells are spindle-shaped and have one central nucleus. The cells are generally arranged in sheets or bundles, rather than the regular grouping that skeletal muscle cells form, and they are connected by gap junctions. Gap junctions are little pores or gaps in the cell membrane that link adjoining cells and they allowing quick passage of chemical messages between cells. Smooth muscle is very different from skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle in terms of structure and function, as shown in Figure below. Smooth muscle contracts slowly and rhythmically.

Figure 21.22

Smooth muscle. The appearance of smooth muscle is very different from skeletal and cardiac muscle. The muscle protein fibers within smooth muscle are arranged very differently to the protein fibers of skeletal or cardiac fibers, shown in (a). The spindly shape of smooth muscle cells can be seen in (b).

Cardiac Muscle

Cardiac muscle, which is found in the walls of the heart, is under control of the autonomic nervous system, and so it is an involuntary muscle. A cardiac muscle cell has characteristics of both a smooth muscle and skeletal muscle cell. It has one central nucleus, similar to smooth muscle, but it striated, similar to skeletal muscle. The cardiac muscle cell is rectangular in shape, as can been seen in Figure below. The contraction of cardiac muscle is involuntary, strong, and rhythmical. Cardiac muscle has many adaptations that makes it highly resistant to fatigue. For example, it has the largest number of mitochondria per cell of any muscle type. The mitochondria supply the cardiac cells with energy for constant movement. Cardiac cells also contain myoglobins (oxygen-storing pigments), and are provided with a large amount of nutrients and oxygen by a rich blood supply.

Cardiac muscle is similar to skeletal muscle in chemical composition and action. However, the structure of cardiac muscle is different in that the muscle fibers are typically branched like a tree branch, and connect to other cardiac muscle fibers through intercalcated discs, which are a type of gap junction. A close-up of an intercalated disc is shown in Figure below. Cardiac muscle fibers have only one nucleus.

Figure 21.23

Cardiac muscle. Cardiac muscle fibers are connected together through intercalated discs.

Structure of Muscle Tissue

A whole skeletal muscle is an organ of the muscular system. Each skeletal muscle consists of skeletal muscle tissue, connective tissue, nerve tissue, and vascular tissue. Skeletal muscles vary considerably in size, shape, and arrangement of fibers. They range from extremely tiny strands such as the tiny muscles of the middle ear to large masses such as the quadriceps muscles of the thigh.

Each skeletal muscle fiber is a single large, cylindrical muscle cell. Skeletal muscle fibers differ from “regular” body cells. They are multinucleated, which means they have many nuclei in a single cell; during development many stem cells called myoblasts fuse together to form muscle fibers. Each nucleus in a fiber originated from a single myoblast. Smooth and cardiac muscle fibers do not develop in this way.

An individual skeletal muscle may be made up of hundreds, or even thousands, of muscle fibers that are bundled together and wrapped in a connective tissue covering called epimysium. Fascia, connective tissue outside the epimysium, surrounds and separates the skeletal muscles. Portions of the epimysium fold inward to divide the muscle into compartments called fascicles. Each fascicle compartment contains a bundle of muscle fibers, as shown in Figure below.

Figure 21.24

Individual bundles of muscle fibers are called fascicles. The cell membrane surrounding each muscle fiber is called the , and beneath the sarcolemma lies the sarcoplasm, which contains the cellular proteins, organelles, and myofibrils. The myofibrils are composed of two major types of protein filaments: the thinner actin filament, and the thicker myosin filament. The arrangement of these two protein filaments gives skeletal muscle its striated appearance.

Skeletal muscle fibers, like body cells, are soft and fragile. The connective tissue covering give support and protection for the delicate cells and allow them to withstand the forces of contraction. The coverings also provide pathways for the passage of blood vessels and nerves. Active skeletal muscle needs efficient delivery of nutrients and oxygen, and removal of waste products, both of which are carried out by a rich supply of blood vessels.

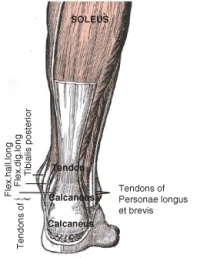

Muscles and Bones

Muscles move the body by contracting against the skeleton. Muscles can only actively contract, they extend (or relax) passively. The ability of muscles to move parts of the body in opposite directions requires that they be attached to bones in pairs which work against each other (called antagonistic pairs). Generally, muscles are attached to one end of a bone, span a joint, and are attached to a point on the other bone of the joint. Commonly, the connective tissue that covers the muscle extends beyond the muscle to form a thick ropelike structure called a tendon, as shown in Figure above. One attachment of the muscle, the origin, is on a bone that does not move when the muscle contracts. The other attachment point, the insertion, is on the bone that moves. Tendons and muscles work together and exert only a pulling force on joints.

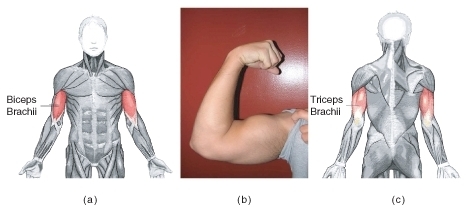

Figure 21.25

Movement of the elbow joint involves muscles and bones. The contraction of the biceps brachii muscle pulls on the radius, its point of insertion, which causes the arm to bend. To straighten the arm, the triceps brachii muscle contracts and pulls on the ulna, this causes the arm to straighten.

For example, when you contract your biceps brachii muscles, shown in Figure above, the force from the muscles pulls on the radius bone (its point of insertion) causing the arm to move up. This action decreases the angle at the elbow joint (flexion). Flexion of the elbow joint is shown in Figure B below. A muscle that causes the angle of a joint to become smaller is called a flexor. To extend, or straighten the arm, the biceps brachii relaxes and the triceps on the opposite side of the elbow joint contracts. This action is called extension, and a muscle that causes a joint to straighten out is called an extensor. In this way the joints of your body act like levers that reduce the amount of effort you have to expend to cause large movements of the body.

Figure 21.26

(a) The position of the biceps brachii. (b) The biceps brachii and triceps brachii act as an atagonistic pair of muscles that move the arm at the elbow joint. The biceps muscle is the flexor, and the triceps, at the back of the arm, is the extensor (c).

Muscle Contraction

A muscle contraction occurs when a muscle fiber generates tension through the movement of actin and myosin. Although you might think the term contraction means only "shortening," the overall length of a contracted muscle may stay the same, or increase, depending on the force working against the muscle.

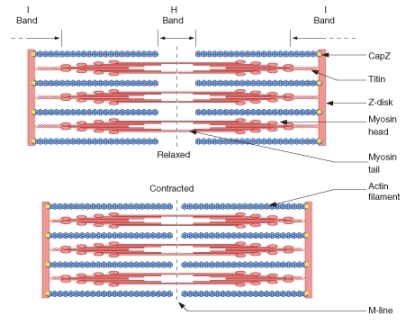

Figure 21.27

The components of muscle contraction. The sacromere is the functional unit of muscle contraction; it reaches from one Z-line to the next (also shown in ). In a relaxed muscle, the actin (thin filament) and myosin (thick filament) overlap. In a muscle contraction, the filaments slide past each other, shortening the sacromere. This model of contraction is called the sliding filament mechanism.

Each muscle fiber contains cellular proteins and hundreds or thousands of myofibrils. Each myofibril is a long, cylindrical organelle that is made up of two types of protein filaments: actin and myosin. The actin filament is thin and threadlike, the myosin filament is thicker. Myosin has a “head” region that uses energy from ATP to “walk” along the actin thin filament (Figure below). The overlapping arrangement of actin and myosin filaments gives skeletal muscle its striated appearance. The actin and myosin filaments are organized into repeating units called sarcomeres, which can be seen in Figure above. The thin actin filaments are anchored to structures called Z lines. The region from one Z line to the next makes up one sacromere. When each end of the myosin thick filament moves along the actin filament, the two actin filaments at opposite sides of the sacromere are drawn closer together and the sarcomere shortens, as shown in Figure below. When a muscle fiber contracts, all sarcomeres contract at the same time, which pulls on the fiber ends.

Figure 21.28

When each end of the myosin thick filament moves along the actin filament, the two actin filaments at opposite sides of the sacromere are drawn closer together and the sarcomere shortens.

The Neuromuscular Junction

For skeletal (voluntary) muscles, contraction occurs as a result of conscious effort that comes from the brain. The brain sends nerve signals, in the form of action potentials to the motor neuron that innervates the muscle fiber, such as the motor neuron in Figure below. In the case of some reflexes, the signal to contract can originate in the spinal cord through a reflex arc. Involuntary muscles such as the heart or smooth muscles in the gut and vascular system contract as a result of non-conscious brain activity or stimuli endogenous to the muscle itself. Other actions such as body motion, breathing, and chewing have a reflex aspect to them; the contractions can be initiated consciously or unconsciously, but are continued through unconscious reflexes. You can learn more about action potentials and reflex arcs in the Nervous and Endocrine Systems chapter.

Figure 21.29

(a) A simplified diagram of the relationship between a skeletal muscle fiber and a motor neuron at a neuromuscular junction. 1. Axon; 2. Synaptical junction; 3. Muscle fiber; 4. Myofibril. (b) A close-up view of a neuromuscular junction. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine is released into the synapse and binds to receptors on the muscle cell membrane. The acetylcholine is then broken down by enzymes in the synapse. 1. presynaptic terminal; 2. sarcolemma; 3. synaptic vesicles; 4. Acetylcholine receptors; 5. mitochondrion. For an animation of the neuromuscular junction see

The Sliding Filament Theory

The widely accepted theory of how muscles contract is called the sliding-filament model (also known as the sliding filament theory), which is shown in Figure below. The presence of calcium ions (Ca2+) allows for the interaction of actin and myosin. In the resting state, these proteins are prevented from coming into contact. Two other proteins, troponin and tropomyosin, act as a barrier between the actin and myosin, preventing contact between them. When Ca2+ binds to the actin filament, the shape of the troponin-tropomyosin complex changes, allowing actin and myosin to come into contact with each other. Below is an outline of the sliding filament theory.

- An action potential (see the Nervous and Endocrine Systems chapter) arrives at the axon terminal of a motor neuron.

- The arrival of the action potential activates voltage-dependent calcium channels at the axon terminal, and calcium rushes into the neuron.

- Calcium causes vesicles containing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to fuse with the plasma membrane, which releases acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft between the axon terminal and the motor end plate of the skeletal muscle fiber.

- Activation of the acetylcholine receptors on the muscle fiber membrane opens its sodium/potassium channel, which triggers an action potential in the muscle fiber.

- The action potential spreads through the muscle fiber's network, depolarizing the inner portion of the muscle fiber.

- The depolarization activates specialized storage sites throughout the muscle, called the sarcoplasmic reticulum, to release calcium ions (Ca++). The sarcoplasmic reticulum is a special type of smooth endoplasmic reticulum found in smooth and skeletal muscle that contains large amounts of Ca++, which it stores and then releases when the cell is depolarized.

- The calcium ions bind to actin filaments of the myofibrils and activate the actin for attachment by the myosin heads filaments.

- Activated myosin binds strongly to the actin filament. Upon strong binding, myosin rotates at the myosin-actin interface which bends a region in the “neck” of the myosin “head,” as shown in Figure 10.

- Shortening of the muscle fiber occurs when the bending neck of the myosin region pulls the actin and myosin filaments across each other. Meanwhile, the myosin heads remain attached to the actin filament, as shown in Figure below.

- The binding of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) allows the myosin heads to detach from actin. While detached, ATP breaks down to adenosine diphosphate and an inorganic phosphate (ADP + Pi). The breaking of the chemical bond in ATP gives energy to the myosin head, allowing it to bind to actin again.

- Steps 9 and 10 repeat as long as ATP is available and Ca++ is present on the actin filament. The collective bending of numerous myosin heads (all in the same direction) moves the actin filament relative to the myosin filament which causes a shortening of the sacromere. Overall, this process results in muscle contraction. The sarcoplasmic reticulum actively pumps Ca++ back into itself. Muscle contraction stops when Ca++ is removed from the immediate environment of the myofilaments.

Figure 21.30

The process of actin and myosin sliding past one another is called crossbridge cycling, and it occurs in all muscle types. Myosin is a molecular motor that moves along the passive actin. Each thick myosin filament has little extensions or heads, that walk along the thin actin filaments during contraction. In this way the thick filament slides over thin filament. The actin filaments transmit the force generated by myosin to the ends of the muscle, which causes the muscle to shorten.

Motor Units

It is important to remember that the sliding filament theory applies to groups of individual muscle fibers which, along with their motor neuron, are called motor units. A single, momentary contraction is called a muscle twitch. A twitch is the response to a single stimulus that can involve a number of motor units. As a stimulus increases, more motor units are stimulated to contract until a maximum level is reached at which point the muscle cannot exert any more force.

Each muscle fiber contracts on an "all or nothing" principle, a muscle fiber either contracts fully, or not at all, and all the fibers in a single motor unit contract at the same time. When a muscle is required to contract during exercise not all motor units are contracted at the same time. Most movements require only a small amount of the total force possible by the contraction of an entire muscle. As a result, our nervous system grades the intensity of muscle contraction by using different numbers of motor units at a time.

Cardiac Muscle Contractions

Cardiac muscle is adapted to be highly resistant to fatigue: it has a large number of mitochondria which allow continuous aerobic respiration; numerous myoglobins (oxygen storing pigment); and a good blood supply, which provides nutrients and oxygen. The heart is so tuned to aerobic metabolism that it is unable to pump well when there is a lack of blood to the heart muscle tissue, which can lead to a heart attack.

Unlike skeletal muscle, which contracts in response to nerve stimulation, and like certain types of smooth muscle, cardiac muscle is able to initiate contraction by itself. As a result, the heart can still beat properly even if its connections to the central nervous system are completely severed. A single cardiac muscle cell, if left without input, will contract rhythmically at a steady rate; if two cardiac muscle cells are in contact, whichever one contracts first will stimulate the other to contract, and so on. This inherent ability to contract is controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

If the rhythm of cardiac muscle contractions is disrupted for any reason (for example, in a heart attack or a cardiac arrest), erratic contractions called fibrillation can result. Fibrillation, which is life threatening, can be stopped by use of a device called a defibrillator. Defibrillation consists of delivering a therapeutic dose of electrical energy to the heart which depolarizes part of the heart muscle. The depolarization stops the fibrillation, and allows a normal heartbeat to start up again. Most types of defibrillators are operated by medical personnel only. However, you may be familiar with an automated external defibrillator (AED) which is shown in Figure below.

Figure 21.31

A wall-mounted automated external defibrillator (AED). Defibrillators are used to shock fibrillating cardiac muscle back into the correct rhythm. AEDs are designed to be able to diagnose fibrillation in a person who has collapsed, meaning that a bystander can use them successfully with little or no training. They are usually found in areas where large groups of people may gather, such as train stations, airports, or at sports events.

Smooth Muscle Contraction

Smooth muscle-containing tissue, such as the stomach or urinary bladder often must be stretched, so elasticity is an important characteristic of smooth muscle. Smooth muscle (like cardiac muscle) does not depend on motor neurons to be stimulated. However, motor neurons of the autonomic nervous system do reach smooth muscle, causing it to contract or relax, depending on the type of neurotransmitter that is released. Smooth muscle is also affected by hormones. For example, the hormone oxytocin causes contraction of the uterus during childbirth.

Figure 21.32

The intestinal tract contains smooth muscle which moves food along by contracting and relaxing in a process called peristalsis. An animation of peristalsis can be viewed at

Similar to the other muscle types, smooth muscle contraction is caused by the sliding of myosin and actin filaments over each other. However, calcium initiates contractions in a different way in smooth muscle than in skeletal muscle. Smooth muscle may contract phasically with rapid contraction and relaxation, or tonically with slow and sustained contraction. The reproductive, digestive, respiratory, and urinary tracts, skin, eye, and vasculature all contain smooth muscle. For example, the ability of vascular smooth muscle (veins and arteries) to contract and dilate is critical to the regulation of blood pressure. Smooth muscle contracts slowly and may maintain the contraction (tonically) for prolonged periods in blood vessels, bronchioles, and some sphincters. In the digestive tract, smooth muscle contracts in a rhythmic peristaltic fashion. It rhythmically massages products through the digestive tract, shown in Figure above, as the result of phasic contraction.

Energy Supply for Muscle Contraction

Energy for the release and movement of the myosin head along the actin filament comes from ATP. The role of ATP in muscle contraction can be observed in the action of muscles after death, at which point ATP production stops. Without ATP, myosin heads are unable to release from the actin filaments, and remain tightly bound to it (a protein complex called actomyosin). As a result, all the muscles in the body become rigid and are unable to move, a state known as rigor mortis. Eventually, enzymes stored in cells are released, and break down the actomyosin complex and the muscles become "soft" again.

Cellular respiration is the process by which cells make ATP by breaking down organic compounds from food. Muscle cells are able to produce ATP with oxygen which is called aerobic respiration, or without oxygen, an anaerobic process called anaerobic glycolysis or fermentation. The process in which ATP is made is dependent on the availability of oxygen (see Cellular Respiration chapter).

Aerobic ATP Production

During everyday activities and light exercise, the mitochondria of muscle fibers produce ATP in a process called aerobic respiration. Aerobic respiration requires the presence of oxygen to break down food energy (usually glucose and fat) to generate ATP for muscle contraction. Aerobic respiration produces large amounts of ATP, and is an efficient means of making ATP. Up to 38 ATP molecules can be made for every glucose molecule that is broken down. It is the preferred method of ATP production by body cells. Aerobic respiration requires large amount of oxygen, and can be carried out over long periods of time. As activity levels increase, breathing rate increases to supply more oxygen for increased ATP production.

Anaerobic ATP Production

When muscles are contracting very quickly, which happens during vigorous exercise, oxygen cannot travel to the muscle cells fast enough to keep up with the muscles’ need for ATP. At this point, muscle fibers can switch to a breakdown process that does not require oxygen. The process, called anaerobic gylcolysis (sometimes called anaerobic respiration) breaks down energy stores in the absence of oxygen to produce ATP.

Anaerobic glycolysis produces only two molecules of ATP for every molecule of glucose, so it a less efficient process than aerobic metabolism. However, anaerobic glycolysis produces ATP about 2.5 times faster than aerobic respiration does. When large amounts of ATP are needed for short periods of vigorous activity, glycolysis can provide most of the ATP that is needed. Anaerobic glycolysis also uses up a large amount of glucose to make relatively small amounts of ATP. In addition to ATP, large amounts of lactic acid are also produced by glycolysis. When lactic acid builds up faster than it can be removed from the muscle, it can lead to muscle fatigue. Anaerobic glycolysis can be carried out for only about 30 to 60 seconds. Some recent studies have found evidence that mitochondria inside the muscle fibers are able to break down lactic acid (or lactate) to produce ATP, and that endurance training results in more lactate being is taken up by mitochondria to produce ATP.

Functions of Skeletal Muscle Contraction

In addition to movement, skeletal muscle contraction also fulfills three other important functions in the body: posture, joint stability, and heat production.

- Joint stability refers to the support offered by various muscles and related tissues that surround a joint.

- Heat production by muscle tissue makes them an important part of the thermoregulatory mechanism of the body. Only about 40 percent of energy input from ATP converts into muscular work, the rest of the energy is converted to thermal energy (heat). For example, you shiver when you are cold because the moving (shivering) skeletal muscles generate heat that warms you up.

- Posture, which is the arrangement of your body while sitting or standing, is maintained as a result of muscle contraction.

Types of Muscle Contractions

Skeletal muscle contractions can be categorized as isometric or isotonic.

An isometric contraction occurs when the muscle remains the same length despite building tension. Isometric exercises typically involve maximum contractions of a muscle by using:

- the body's own muscle (e.g., pressing the palms together in front of the body)

- structural items (e.g., pushing against a door frame)

- contracting a muscle against an opposing force such as a resistance band, or gravity, as shown in Figure below

Figure 21.33

Pushing a heavy object involves isometric contractions of muscles in the arms and in the abdomen. This mans grip on the trolley involves isometric contractions of the hand muscles. The muscles in his legs are contracting isotonically.

An isotonic contraction occurs when tension in the muscle remains constant despite a change in muscle length. Lifting an object off a desk, walking, and running involve isotonic contractions. There are two types of isotonic contractions: concentric and eccentric. In a concentric contraction, the muscle shortens while generating force, such as the shortening of the biceps brachii in your arm when you lift a glass to your mouth to take a drink, or a set of dumbbells, as shown in Figure below.

During an eccentric contraction, the force opposing the contraction of the muscle is greater than the force that is produced by the muscle. Rather than working to pull a joint in the direction of the muscle contraction, the muscle acts to slow the movement at the joint. Eccentric contractions normally occur as a braking force in opposition to a concentric contraction to protect joints from damage. The muscle lengthens while generating force. Part of training for rapid movements such as pitching during baseball involves reducing eccentric braking which allows greater power to be developed throughout the movement.

Figure 21.34

An example of an isotonic contraction. The biceps brachii contract concentrically, raising the dumbbells.

Muscles and Exercise

Figure 21.35

You dont have to be super fit to play in snow, but it might help!

As we learned earlier in this lesson, your muscles are important for carrying out everyday activities, whether you are picking up a glass of orange juice, walking your dog, or snow wrestling (Figure above). The ability of your body to carry out your daily activities without getting out of breath, sore, or overly tired is referred to as physical fitness. For example, a person who becomes breathless and tired after climbing a flight of stairs is not physically fit.

We cannot discuss the effect of exercise on your muscles without first clarifying the confusion between some common terms. It is easy to get confused with the relationship between “physical fitness,” “physical activity,” and “physical exercise.” Some people may think they cannot fit physical activity into their lives because they are unable to afford to join a gym, they do not have the time be involved in an organized sport, or they do not want to lift weights. However, physical activity encompasses so much more than just “working out.” Physical activity is any movement of the body that causes your muscles to contract and your heart rate to increase. Everyday activities such as carrying groceries, vacuuming, walking to class, or climbing a flight of stairs are physical activities.

Being physically active for 60 minutes a day for at least five days a week helps a person to maintain a good level of physical fitness and also helps him or her to decrease their chance of developing diseases such as cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and certain forms of cancer. Varying levels of physical activity exist: from a sedentary lifestyle in which there is very little or no physical activity, to high-level athletic training. Most people will find themselves somewhere in the middle of this wide spectrum.

Physical exercise is any activity that maintains or improves physical fitness and overall health. Exercise is often practiced to improve athletic ability or skill. Frequent and regular physical exercise is an important component in the prevention of some lifestyle diseases such as heart disease, cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes and obesity. Regular exercise is also helpful with reduction in, or avoidance of symptoms of depression. Regular exercise improves both muscular strength and endurance. Muscular strength is the ability of the muscle to exert force during a contraction. Muscular endurance is the ability of the muscle to continue to contract over a period of time without getting fatigued. Regular stretching improves flexibility of the joints and helps avoid activity-related injuries.

Effect of Exercise on Muscles

Exercises are generally grouped into three types depending on the overall effect they have on the human body:

- Aerobic, or endurance, exercises, such as cycling, walking, and running, shown in Figure below, increase muscular endurance.

- Anaerobic exercises, such as weight training, shown in Figure below, or sprinting increase muscle strength.

- Flexibility exercises, such as stretching, improve the range of motion of muscles and joints.

Aerobic exercise causes several changes in skeletal muscle: mitochondria increase in number, the fibers make more myoglobin, and more capillaries surround the fibers. These changes result in greater resistance to fatigue and more efficient metabolism. Aerobic exercise also benefits cardiac muscle. It results in the heart being able to pump a larger volume of blood with each beat due to an increase in the size of the heart’s ventricles.

Figure 21.36

Running is a form of aerobic exercise.

Anaerobic, or resistance, exercises cause an increase in muscle mass. Muscles that are trained under anaerobic conditions develop differently giving them greater performance in short duration-high intensity activities. As a result of repeated muscle contractions, muscle fibers develop a larger number of mitochondria and larger energy reserves.

During anaerobic exercise, muscles break down stored creatine phosphate to generate ATP. Creatine phosphate is an important energy store in skeletal muscle. It is broken down to form creatine for the 2 to 7 seconds following intense contractions. After several seconds, further ATP energy is made available to muscles by breaking down the storage molecule glycogen into pyruvate through glycolysis, as it normally does through the aerobic cycle. What differs is that pyruvate, rather than be broken down through the slower but more energy efficient aerobic process, is fermented to lactic acid. Muscle glycogen is restored from blood sugar, which comes from the liver, from digested carbohydrates, or from amino acids which have been turned into glucose.

Two types of muscle fibers make up skeletal muscle:

- Slow twitch muscle fibers, or "red" muscle, is dense with capillaries and is rich in mitochondria and myoglobin, giving the muscle tissue its characteristic red color. It can carry more oxygen and sustain aerobic activity. The endurance of slow twitch muscles is increased by aerobic training.

- Fast twitch muscle fibers are the fastest type of muscle fibers in humans. These fibers tend to have fewer mitochondria than slow twitch fibers do, but they have larger energy stores. They can contract more quickly and with a greater amount of force than slow-twitch fibers can. Fast twitch fibers can sustain only short, anaerobic bursts of activity before muscle contraction becomes painful. Fast twitch muscle fibers become faster and stronger in response to short, intense activities such as weight training.

Both aerobic and anaerobic exercise also work to increase the mechanical efficiency of the heart by increasing cardiac volume (aerobic exercise), or myocardial thickness (strength training). Anaerobic training results in the thickening of the heart wall to push blood through arteries that are squeezed by increased muscular contractions.

Figure 21.37

This weightlifter shows muscular hypertrophy which he has gained through anaerobic exercise.

Muscular Hypertrophy

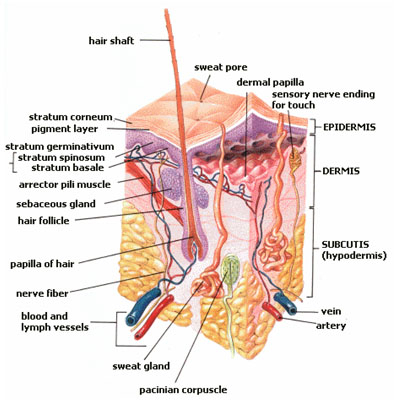

Hypertrophy is the growth in size of muscle fibers and muscles, as shown in Figure above. Aerobic exercise does not tend to cause hypertrophy even though the activity may go on for several hours. That is why long-distance runners tend to be slim, especially in the upper body. Hypertrophy is instead caused by high-intensity anaerobic exercises such as weight lifting or other exercises that cause the muscles to contract strongly against a resisting force. As a result of repeated muscle contractions, muscle fibers develop a larger number of mitochondria and larger energy reserves. The muscle fibers also develop more myofibrils, and each myofibril contains more actin and myosin filaments. The effect of this activity is hypertrophy of the stimulated muscle.