2

Colonial Consumption and Community Preservation

From Trade Beads to Taffeta Skirts

CRAIG N. CIPOLLA

Monday, April 30, 1917, was a fairly ordinary day for Belva Mosher (1917–1923:51). She began her diary entry with a short description of the cool, wet Wisconsin weather; an unfortunate spring rain kept her indoors for much of the day. She went on to mention several mundane events before concluding the day’s entry: in the morning she visited with her friend Ella and, later that afternoon, sent away to Sears & Roebuck for a silk taffeta skirt. For me, this “everyday” example of consumption is of particular interest because Belva was indigenous. More specifically, she was a member of the Brothertown Indians (Cipolla 2013a; Jarvis 2010; Silverman 2010), a multitribal Christian community that formed on the U.S. east coast approximately 130 years before her diary entry. Belva’s ancestors relocated to central New York state in the late eighteenth century and moved again during the second quarter of the nineteenth century to current-day Brothertown, Wisconsin, the place Belva called home (map 2.1).

This particular example of consumption fits well within the purview of archaeology, particularly recent studies that delve into the contemporary past. For some, the consumption of mass-marketed goods like Belva’s skirt presents an intriguing challenge: How were ethnic, racial, class, and gender relations refracted and negotiated in such practices and materials? To rephrase using Latour’s terminology (2005), how did local events of consumption reproduce, challenge, and transform the broader social categories listed above in concert with other local agencies? Recognizing the unique and valuable perspective offered through archaeology, Paul Mullins (2011) argues for the untapped potential of archaeological consumption studies for addressing such questions. He first acknowledges the antiquated models of consumption that continue to inform certain archaeological approaches, referring to reductionist treatments that typically frame consumption as solely determined by broader forces of supply and demand. These approaches fall into the scalar trap, mentioned in chapter 1 of this volume, that frames “the local” as always subservient to “the global.” Mullins prefers a more nuanced approach that recognizes the complexities and interconnections of various power structures and agencies involved in consumption. He defines consumption broadly as the socialization of material goods, noting its importance in self-determination and collective identification (Mullins 2004, 2011). Regarding the study of indigenous consumption practices in colonial contexts specifically, he highlights the limited importance placed on such goods by archaeologists.

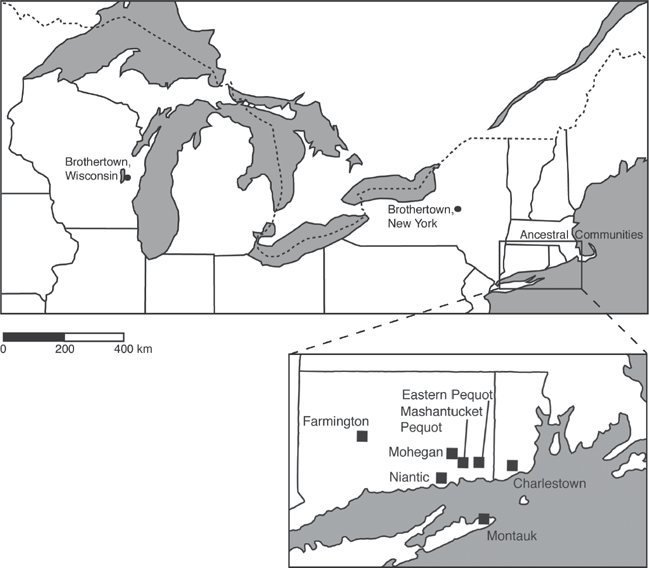

Map 2.1. Locations of both Brothertown settlements and the seven ancestral reservation communities. Map by the author.

Indeed, the history of archaeological studies of culture contact and colonialism in North America shows tendencies to value European-produced goods recovered from Native American contexts as either dating mechanisms or as indicators and barometers of cultural change (as critiqued in Rubertone 2000 and Silliman 2005, 2009). In decades past, archaeologists treated European-manufactured material culture found in Native American contexts as straightforward indicators of cultural loss. This general pattern also holds for studies of colonial consumption in the ancient world. In his study of Greek colonialism in ancient France, for example, Michael Dietler (2010:60) notes that archaeologists and historians tend to treat Greek consumption of indigenous goods as fundamentally different from indigenous consumption of Greek things. Similarly, in his 2011 study of Roman warfare and weaponry, Simon James points out that to truly understand Roman military history one must also understand those who opposed Roman conquest. The focus of his study, Roman weaponry, attests to frequent Roman adoptions of foreign military styles and materials. In each of these very different forms of colonialism, colonizers are often assumed to maintain their authenticity despite observed material changes, while indigenous populations are seen as fundamentally different (acculturated) because of observed material changes.

The deficiencies highlighted here stem largely from conflations of scale (and the a priori assumptions about different agencies that they mask, or at least obscure). In this sense, my approach parallels that of Latour’s actor network theory in that I strive to flatten out these scales in hopes of exposing and challenging the assumptions they conceal. In Latour’s words (2005:204), “No place dominates enough to be global and no place is self contained enough to be local.” One must follow connections from local interactions to “the other places, times, and agencies through which a local site is made to do something” (173). The archaeological contexts discussed below have been traditionally dealt with in a lopsided manner, treating the local as subservient to broader forces such as European expansion, globalization, and capitalism. First, we must understand that these forces are produced locally through their various connections to the people and things that constituted them (often silently, as noted in Latour 2005:195). Second, we must recognize the other connections and agencies inside these local conditions, including non-European people, things, and practices. For these reasons, scrutiny is needed over our terminology and the conceptual baggage it cloaks, and various scalar terms often used haphazardly in archaeological interpretation—such as “indigenous,” “foreign,” “native,” “local,” and “nonlocal”—need to be challenged (Hayes, this volume; Hayes and Cipolla, this volume; Mullins and Ylimaunu, this volume).

Of course, archaeologists and historians are not the only ones with such rigid understandings of the “nonlocal” things that became socialized in indigenous societies. Dietler (2010:63) reminds us that through the ages, “foreign” goods were frequently seen by colonists and colonized alike as tools for controlling one another (also Wells, this volume). For instance, in colonial New England, this premise is supported by the work of seventeenth-century missionary John Eliot (Bross and Wyss 2008; Cogley 1999; O’Brien 1997; Salisbury 1974), who saw English goods and practices as vehicles of cultural and religious change in indigenous societies of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Mrozowski, Gould, and Law Pezzarossi, this volume). The archaeology of Eliot’s praying villages complicate and challenge his understanding of English goods and their purposes in Indian communities. Deterministic understandings of material culture such as Eliot’s are still very much alive in contemporary American society, both in everyday understandings of Native American identities and in federal law (Cipolla 2013b).

In the spirit of consumption studies that move beyond economic determinism to consider consumer agency and choice (Douglas and Isherwood 1979; Miller 1987, 1995; Mullins 2004, 2011; Silliman and Witt 2010), I explore select indigenous consumption practices during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. An exhaustive treatment of this vast topic is well beyond the scope of this chapter. Yet, this cursory analysis highlights the promise of such a project by providing some general patterns along with a discussion of their implications for the past, present, and future of colonial North America. Contemporary archaeologies of colonialism reject the double standards introduced above. In the case of Native North America this means addressing the complexities of subaltern agency (always constrained), cultural appropriation, and cultural entanglement that are folded into practices of consumption and consumer choice (along with forces often typified as “global” in scope, such as capitalism). Archaeological considerations of Native American consumption are still few and far between. They are also dominated by the assumption that colonial politics color all facets of Native social life from moments of culture contact onward. While I do not deny the importance of colonial tensions, which certainly still exist, I argue that archaeologists must challenge such black-and-white portrayals of colonial history by approaching Native American consumption in terms of social dynamics within Native communities and by considering the impacts that certain forms of consumption had over the long term. This project goes beyond basic questions of acceptance or rejection of non-Indian-produced goods to consider how “foreign” things were socialized and to what effect (following Mullins 2011).

I place the observed patterns of consumption into their broader historical contexts, accepting arguments that cultural change and continuity are forever entangled (Ferris 2009; Silliman 2009; Scheiber and Mitchell 2010). Even in the most unexpected of places, archaeologists taking this approach have the potential to reveal connections between colonial practices and deeper traditions, spiritualities, and identities (for example, Crosby 1988). This point is nicely illustrated by the excavation of Magunkaquog, one of Eliot’s praying villages in Ashland, Massachusetts (Mrozowski et al. 2009; Mrozowski, Gould, and Law Pezzarossi, this volume). Beneath three corners of the foundation of a structure interpreted as the communal meetinghouse of the village, Stephen Mrozowski and his colleagues found heat-treated crystals. Other researchers have documented the use and meaning of crystals in various Algonquian societies (Miller and Hamell 1986; White 1991:99; Williams 1973 [1643]). Miller and Hamell (1986:318) argue that crystals were “other worldly” for some indigenous groups, assuring “long life, physical and spiritual well-being, and success.” Based on these findings, it seems plausible that at least some of the inhabitants of Magunkaquog saw Christianity as a complement to—rather than as a replacement of—long-standing Algonquian spiritual practices and symbols (Mrozowski et al. 2009:456). I argue that similar hints of ancient continuities are still evident in the archaeological remains of Native consumption in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries. Yet, the general patterns discussed below also shed light on colonialism as general process, including ancient, historical, and contemporary colonial contexts.

Background

I synthesize published data from four related contexts (map 2.1): the Eastern Pequot Reservation in North Stonington, Connecticut (Silliman 2005, 2009; Silliman and Witt 2010; also Hayden 2012 and Witt 2007), the neighboring Mashantucket Pequot Reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut (McBride 1990; Kevin McBride, personal communication), Brothertown, New York, and Brothertown, Wisconsin (Cipolla 2013a, 2013b). The Eastern and Mashantucket Pequot are closely related since they were part of the same group until the mid-seventeenth century, at which time the English separated the Pequot onto two different reservations (Den Ouden 2005; McBride 1990). The Brothertown Indian community (Belva’s group) incorporated Pequot peoples from each reservation along with Narragansetts, Eastern and Western Niantics, Mohegans, Tunxis, and Montauketts (Cipolla 2013a; Jarvis 2010; Silverman 2010). Factions of each of these northeastern reservation communities opted to leave their respective homelands for the opportunity to start anew in Brothertown, New York, subsequently moving to current-day Wisconsin.

Having recognized these connections, it is also important to point out the differences between the Eastern Pequot, Mashantucket Pequot, and Brothertown communities. For example, sites studied on the Mashantucket and Eastern Pequot reservations may have been created and used by individuals and families of comparatively lesser means than individuals and families living in the Brothertown settlements. This is partially because Brothertown Indians had more arable land than did reservation communities back east. The first generations of Brothertown Indians also made conscious choices to leave coastal reservations, rejecting traditional political structures and spiritualities while also leaving friends and family members behind (Cipolla 2013a).

I use data collected from each of these contexts to address two seemingly different forms of consumption: household items, such as ceramics, and grave markers. I see these two forms of consumption as distinct in terms of discursiveness, time scale, and social engagement. Many grave markers produced during the modern era were designed to explicitly say something about the deceased, while household tablewares functioned as part of a much more subtle form of social discourse (Mullins and Ylimaunu, this volume) that was perhaps unknown to—or resisted by—indigenous communities. Gravestones are also designed to last longer than ceramics. Finally, compared to household spaces, cemeteries were potentially visible to different types of people over time.

Notwithstanding these inferred distinctions, archaeologists must use caution when applying labels to past peoples and practices (Fowles 2013). It is highly plausible that Pequot and Brothertown peoples living in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries regarded these practices differently than their descendants do today. The quotidian and the sacred may have been far less secularized than in contemporary perspectives. For instance, one of my indigenous colleagues once asked my field students to define “sacred” and pointed out that his ancestors likely applied the concept more liberally than he does today, perhaps not even distinguishing between the two categories. Due to these interpretive challenges, I treat these two types of consumption in terms of the contextual differences outlined above rather than assuming fundamental distinctions between household items and grave markers.

Building Homes and Setting Tables

With only a few exceptions, archaeologists have yet to pay much attention to the materiality of everyday life in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Native contexts. To date, Stephen Silliman (2009) has reported the results of three household excavations from his ongoing work on the Eastern Pequot Reservation in North Stonington, Connecticut (also Hayden 2012; Witt 2007). These households provide a promising albeit tentative baseline with which to track Eastern Pequot consumption patterns between the mid-eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. Diagnostic material culture from the earliest household indicates an approximate date of occupation between 1740 and 1760 (Silliman 2009:219). However, these dates should be taken with a grain of salt since household contexts from the nearby Mashantucket Pequot Reservation often yield mean ceramic dates that predate the recorded period of occupation by five or more years, indicating the consumption of out-of-date or second-hand ceramics (Kevin McBride, personal communication). Silliman (2009:219–220) describes this mid-eighteenth-century dwelling as either a wigwam with “some nailed elements and at least one glass window pane or, alternatively, a small wooden framed structure with no foundation.” He goes on to discuss the presence of nonindigenous-produced ceramics, both European and locally made, such as basic redware, Astbury-type ware, Staffordshire slipware, white salt-glazed stoneware, and Brown Reserve porcelain (Silliman 2009:220; Silliman and Witt 2010). In addition to ceramics, the dwelling contained a variety of European- or Euro-American-made items such as kettle fragments, straight pins, glass beads, and clay pipe fragments.

Kevin McBride has excavated similar types of dwellings on the neighboring Mashantucket Reservation. Like Silliman, McBride (1990:113) interprets these mid-eighteenth-century structures as a combination of wigwam and Euro-American-style framed houses. He and Sturtevant (1975) discuss observations recorded in the mid- to late eighteenth century by Ezra Stiles, an American academic who was keenly interested in Native American culture in New England. Stiles recorded the typical Pequot or Niantic dwelling structure in the 1760s as a “traditional” or unmodified wigwam. He noted the presence of “plates” in the wigwam (Sturtevant 1975:438); although he gave no further detail, these plates were likely of European manufacture. In summary, the mid-eighteenth-century structures studied by Silliman and McBride were distinct from the earlier structures described by Stiles, though the material culture might have been similar in the sense that it was possibly European- or Euro-American-produced.

The second structure described by Silliman was likely used during the last four decades of the eighteenth century. Distinct from the first, this structure included “significant surface and subsurface components as well as prominent alterations to the surrounding landscape” (Silliman 2009:220). Most notably, the site contained a comparatively large amount of fieldstone architectural debris, including two collapsed stone chimneys along with several other intact archaeological features, among them a full cellar. Silliman uncovered a wide variety of European-produced ceramics at this second structure, including white salt-glazed stoneware, slipware, agateware, creamware, early forms of pearlware, English brown stoneware, and Chinese porcelain (ibid.; also Silliman and Witt 2010). Compared to the older dwelling, this site contained an even wider variety of nonindigenous-produced material culture (Silliman 2009:220). Similar to the first, this structure roughly resembles contemporaneous structures studied by McBride (1990:113) on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation. For instance, McBride notes an increase in fieldstone architectural elements at this time. Research on the types of material culture recovered from Mashantucket Pequot households dating to this period is still under way (Cipolla and McBride 2014).

The third dwelling reported by Silliman (2009:221) dates approximately to the first three or four decades of the nineteenth century. In form, this structure was a framed house with a large stone chimney, a small crawl space, and a rich trash deposit in a pit feature just outside the house. Similar to the other dwellings discussed by Silliman, this last structure also contained redware, creamware, pearlware, English brown stoneware, and porcelain, along with pipe fragments, window and bottle glass, and a variety of other nonindigenous-produced items (ibid.). Of note, my own research on this site focused on the faunal remains (Cipolla 2005, 2008; Cipolla, Silliman, and Landon 2007) and offered insights into how European-produced materials such as metal knives and bottle glass may have been socialized in private reservation household contexts. Analysis of cut marks found on animal remains indicated that nearly half of the marks were made with metal cutting implements, while more than a quarter were made with nonmetal, chipped tools (possibly glass). This interpretation was strengthened with the excavation of the second structure discussed above, which contained a few stone flakes and chipped-glass artifacts (Silliman 2009:221).

This architectural pattern mirrors the general patterns observed archaeologically by McBride (1990:113) on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation. Complementing the archaeology from this general period, in 1762 Ezra Stiles mentioned twenty-three Mashantucket Pequot dwellings, sixteen of which were described as wigwams and seven as framed houses (McBride 1990:113–114). Based on the archaeology and ethnohistory of the reservation, McBride interprets framed houses as the typical house form on the reservation by the mid-nineteenth century.

In summary, the two Pequot reservations provide important information on changes in household architecture and associated material culture during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. There is no indication that the ceramic sherds studied on either reservation represent complete matching sets of tableware. This makes sense when considering the means by which Pequot peoples acquired such goods. Ledger books kept by Jonathan Wheeler, a white farmer and merchant living in the vicinity of the Pequot reservations, document Pequot men working as day laborers on the farm in exchange for cash and for credit that were often used to purchase seeds, vegetables, and goods from Wheeler or from local merchants through Wheeler (Silliman and Witt 2010:54–57; Witt 2007). Pequots also traded fish and wool to Wheeler in exchange for credit.

The presence of unexpected wares like porcelain in impoverished reservation contexts speaks to a theme discussed by Mullins and Ylimaunu (this volume). Like Mullins and Ylimaunu’s silver items, the porcelain in these indigenous contexts demonstrates the need to move beyond the compilation of “laundry lists” of recovered ceramics to actually delving into the biographies of such items and asking how they were acquired, how they were used, and how their users’ patterns of consumption compare to those among other contemporaneous sites. I would tentatively suggest that despite the similarities in the types of material culture present in these varied contexts, there were significant differences among households on each reservation and between Pequot and English households such as frequencies of European-produced ceramics, possible differences in use wear, and so forth. However, a detailed comparison of the various contexts has yet to be made.

Compared with the Pequot reservations, there has been little excavation conducted on Brothertown homes in New York and Wisconsin. Despite this lack of archaeological data, archival evidence does provide some initial clues into the structure of Brothertown dwellings and a few hints concerning Brothertown consumption of everyday household items. For example, on September 26, 1799, Timothy Dwight, president of Yale University, passed through Brothertown, New York, and recorded his observations (in Love 1899:304–305). Dwight held a strong interest in observing “civilized” Indian life and was impressed with the Brothertown Indians. He described an agricultural landscape: “Here forty families of these people have fixed themselves in the business of agriculture.” He noted that only three families (among sixty documented as living in Brothertown at this time) lived in framed houses, with most other families living in log cabins similar to “those of whites.” Dwight was particularly impressed with the household of Amos Hutton, writing, “He is probably the fairest example of industry, economy, and punctuality, which these people can boast” (304).

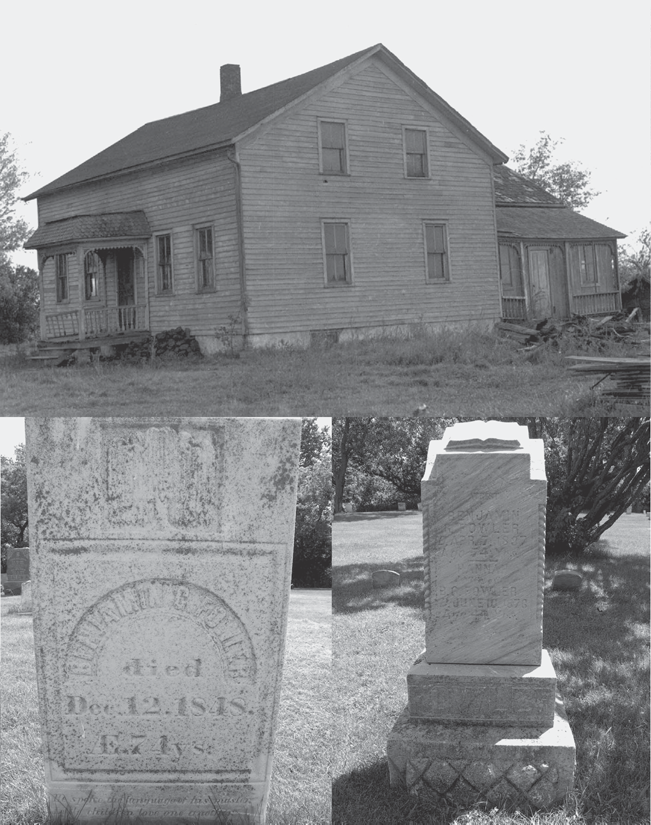

A collection of photographs of Brothertown homes in the next Brothertown settlement, in Wisconsin, affirms that most Brothertown Indians lived in either log cabins or framed structures like the house pictured on the top in figure 2.1. Built in 1842, this was the home of Benjamin Garret Fowler I, an important leader in the Brothertown community.

Brothertown record books (Brothertown Indians 1796) dating to the late eighteenth century provide indirect evidence of imported household goods. For instance, on November 15, 1796, the community received a large shipment of foodstuffs (a few barrels of pork), livestock (four yoke of oxen, six cows, fifty sheep) along with manufactured goods—“crockery, pens needles & sundry small articles” (34). On December 17 of the same year, the community received another large shipment, which included two dozen bibles, three gross blue cups and saucers, and two dozen flowered tea pots (42). Limited excavations in Brothertown, Wisconsin, uncovered European-produced earthenwares and stonewares along with a variety of metal objects, including fragments of food-related cans and agricultural hardware.

Figure 2.1. Benjamin Garret Fowler I’s house (top) and grave marker, Brothertown, Wisconsin (bottom left); shared grave marker of Benjamin Garret Fowler II and his wife, Hannah, Brothertown, Wisconsin (bottom right). The inscription on Benjamin Garret Fowler I’s stone reads: “Benjamin G. Fowler died Dec. 12, 1848 AE 74 y’s, He spoke the language of his Master, little children love one another.” The epitaph likely refers to Benjamin’s role as a minister and elder in the Freewill Baptist community at Brothertown (Love 1899:345). The stone of Benjamin’s son and daughter-in-law reads, “AT REST, BENJAMIN G. FOWLER, D. APRIL 7 1887, Age 74 Yrs., HANNAH, WIFE of B. G. FOWLER, D. JUNE 10 1876, Age 44 Yrs.” House photo from author’s collection, courtesy of the Brothertown Indian Nation. Cemetery photos by the author.

Marking Sacred Spaces

During the Great Awakening of the early eighteenth century, Christianity spread through much of Native New England and many Native peoples began regularly marking the graves of their loved ones above the ground with unmodified fieldstones, stone piles, and stones modified into head- and footstones (Cipolla 2013a). Occasionally, Native communities marked burials from this period in ways similar to those of their Euro-American neighbors, with inscribed stones purchased from semiprofessional and professional carvers. This practice was rare, however. For instance, out of all of the cemeteries on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation, only one text-bearing gravestone, dating to the late nineteenth century, was purchased from a professional carver during the entirety of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries (ibid.). This dearth of purchased stones certainly ties to economic limitations, but it also complied with traditional modes of commemoration in Native New England, discussed shortly.

There are many parallels between pre-twentieth-century cemeteries on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation and those in Brothertown, New York. Between the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, Brothertown Indians created no fewer than seven burial grounds in their first settlement (ibid.). Several Brothertown stones also sit in a multi-ethnic cemetery founded in the early nineteenth century by the increasing white population in the area. The first few generations of Brothertown Indians largely replicated the forms of commemoration practiced in their home communities at the time of the Brothertown exodus. Even the grave of Amos Hutton, whom Timothy Dwight mentioned as prosperous and well-off, was likely marked with a blank limestone grave marker, suggesting that this choice was not determined by the cost of store-bought markers. Rather than purchasing headstones from carvers, most Brothertown Indians marked the graves of their loved ones with locally made blank gravestones that ranged in form from unmodified fieldstones to stones roughly shaped to resemble those found in local white, Christian cemeteries.

The Brothertown Indians only began purchasing grave markers from professional carvers during the nineteenth century, and this practice became increasingly popular after 1830 (ibid.). The new store-bought markers often displayed inscribed names, death dates, and other biographical details of the deceased along with occasional décor and imagery such as the urn and willow motif. Just as they were beginning to radically transform their commemoration practices in the 1830s (by becoming consumers), the Brothertown Indians migrated once again. Ninety-nine percent of the markers in the Wisconsin settlement were store-bought. The assemblage includes headstones, obelisks, ledgers or flat slabs, and several other marker types catalogued in eight cemeteries. Figure 2.1 (bottom) shows a set of typical Brothertown grave markers. Compared to neighboring non-Brothertown Indian stones, the inscription details—combined with specific knowledge of Brothertown genealogy—and the general spatial distribution of the stones are the only means of distinguishing Brothertown grave markers from those of outsiders (Cipolla 2013a). As discussed next, I see the shift to these types of grave markers as partially related to Brothertown Indians’ efforts to blur social distinctions between whites and Indians in Brothertown, Wisconsin.

Consuming the Quotidian and the Sacred

On the two Pequot reservations, European-produced ceramics and other household items largely replaced Native-made materials (specifically pottery) by the mid-eighteenth century, while there are no indications that Brothertown Indians in either New York or Wisconsin made their own ceramics. There is still much work to be done in terms of researching the ways in which Brothertown families socialized “foreign” things, but the archival record does suggest that Brothertown Indians had access to a plethora of European-produced goods, including ceramics. Overall, this brief synthesis of consumption on four closely related colonial contexts emphasizes the need for further comparison across reservation and other site boundaries. Further synthesis could shed more light on the shifting materialities of reservation households in terms of functionality, symbolism, and social relations, both intra- and intercommunally.

Changes in everyday material culture and cemetery material culture occurred in similar sequences across the different sites. Compared to the household contexts summarized, cemeteries changed much later. In Brothertown, New York, Brothertown Indians only purchased eight grave markers from professional stonemasons during the first three decades of the nineteenth century. The cemetery data from both Brothertown settlements show a sharp increase in purchased stones during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. This change is particularly evident in the cemeteries of Brothertown, Wisconsin, which house only four “homemade” (blank) grave markers, compared to 266 purchased stones. On the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation, there was at least a 150-year gap between changes in household consumption and changes in cemetery consumption. There was approximately an 80-year lag between shifts in Brothertown household consumption and changes in grave marker consumption. So, why was there such a delay between the consumption of nonindigenous-produced household items and nonindigenous-produced grave markers? With this question, I aim to explore much more than teleological arguments that employ purely technological or economic explanations as their central tenets.

To explain these patterns primarily in terms of financial issues oversimplifies colonial interaction and indigenous choice. Perhaps New England Indians simply did not have the money to purchase professionally made grave markers with inscriptions. This was certainly an important factor, but it was far from deterministic. As outlined in Silliman and Witt’s (2010) important research, during the eighteenth century, some Pequot people had the financial means to purchase grave markers if they wished. Furthermore, the Brothertown Indians had productive farms, especially when compared to those of their families and friends who stayed behind on the home reservations. More specifically, there is evidence that Brothertown Indians paid two to three dollars for coffins in New York, while cheap gravestones likely sold for about four dollars and up during the early nineteenth century (Cipolla 2013a). Further demonstrating the independence of economic prosperity and the purchase of gravestones, Brothertown Indians only began purchasing stones en masse after 1830, precisely when the first settlement was becoming crowded, making farmland scarce and money tight (Jarvis 2010).

Others might explain this sequence in terms of literacy. Perhaps Indians did not purchase professionally made markers because most of them did not read. Given the prevalence of Indian schools and missionary efforts near each reservation during the eighteenth century (Fish 1983; Jarvis 2010; Love 1899; Silverman 2010), at least some individuals residing on reservations were familiar with the English language in some capacity. The Brothertown Indians, who were largely literate by the nineteenth century (Cipolla 2012a, 2012b), also avoided purchasing professionally made markers bearing text for several decades after gaining fluency in the English language. Also of note, five of the stones that they did purchase in the 1830s and 1840s were shaped by professional stonemasons but left completely blank (Cipolla 2013a).

I see the sequences of changing consumption patterns as related to a combination of these factors but also as driven by changing social relations and memory practices in Indian communities during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Text-bearing grave markers took on new functions in communities like those of the Brothertown Indians, but the changes were far from straightforward replacements of indigenous practices and things (“the local”) with European practices and things (“the nonlocal”). New forms of grave markers used in Brothertown cemeteries reconfigured enduring traditions of remembrance in coastal Algonquian societies, perhaps further segregating the quotidian from the sacred. New marker types in Brothertown, Wisconsin, also aided Brothertown Indians in their efforts to remain on their lands in a time when the federal government was pushing many Indian groups westward. Text-bearing stones literally allowed the deceased’s loved ones to preserve their genealogical histories in stone, solidifying their rights to family-owned land. However, it is important to point out that by adopting “foreign” conceptions of landownership at this time, Brothertown Indians also held onto the rest of their community. Change and continuity went hand in hand.

The forms of commemoration practiced on eighteenth-century reservations and at both Brothertown settlements, which made use of blank handmade grave markers, represented a significant change from memory practices of the seventeenth century but not an abrupt replacement. These changes had pragmatic implications for the ways in which individuals and families remembered and related to one another (Cipolla 2013a). During the seventeenth century, indigenous communities of New England seemingly avoided using enduring forms of grave markers such as stones (Gibson 1980; Rubertone 2001; Simmons 1970). Outsiders observed Indians leaving garments belonging to the deceased above the graves, on the ground surface, or hung from nearby trees (DeForest 1964 [1851]; Williams 1973 [1643]). The garments were then left untouched and allowed to waste away, creating an iconic relationship between the mortal remains below the ground and the fabrics left out in the elements above it. This general pattern complements ethnohistoric accounts (Morgan 1962 [1851]; Williams 1973 [1643]) that noted that local Native American communities forbade the utterance of names of the deceased. Combined, these parallel practices encouraged a form of social forgetting over the long term. While the omission of purchased, inscribed grave markers in these cemeteries likely ties, in part, to the economic status of Native communities at the time, it should be noted that this pattern also relates to deeper traditions of spirituality and socially instituted forgetting in which emphasis was placed on a community of deceased ancestors who once lived in the deity Cauntantowitt’s house (Simmons 1970). In this scenario, the quotidian and the sacred were perhaps much more closely melded (Rubertone 2001:127) than in modern, secular understandings of the world. (Fowles 2013 presents a postsecular approach to related problems.)

The case of Samson Occom’s grave exemplifies the shift between seventeenth-century commemoration practices and those that emerged in the second quarter of the nineteenth century (Cipolla 2013a). Occom, a Presbyterian minister of Mohegan descent, was one of the Brothertown community’s most famous leaders. At the time of his death in 1792, the Brothertown Indians were a community in transition; they still upheld forms of forgetting that tied back to the seventeenth-century practices just discussed. While Occom’s grave likely sits in the largest communal cemetery in Brothertown, New York, its specific location within it is unknown because the community refrained from using an enduring form of text to mark the grave of its most prominent leader.

New forms of gravestone consumption in the coming decades transformed this tradition further by marking specific burial locations with names and basic biographical information of the deceased etched in stone (figure 2.1). Just as the Brothertown Indians began to embrace new memory practices, they also became U.S. citizens in 1839 with individual land rights (Cipolla 2013a). They petitioned the federal government arguing that they were a progressive group of Native peoples who embraced aspects of colonial change but yet had no means of protecting their lands as their Euro-American neighbors did. They were awarded citizenship, and their land was allotted to individuals and family groups within the community for the first time. The material changes I describe here supported the Brothertown Indians’ general argument, aiding the community in its successful petition. Grave markers that emphasized the individuality of the dead solidified genealogical ties and familial land rights for the living. Benjamin Garret Fowler’s land and house (figure 2.1) were passed down from generation to generation. Grave markers helped solidify these new connections but also served to further transform memory practices and conceptions of personhood and individuality within the community.

Consumption and Community

In Mullins’s review article on the archaeology of consumption (2011:141), he notes that recent studies acknowledge “the complicated effects of commodity consumption across lines of difference.” Such studies focus on the myriad ways in which different groups like overseas Chinese or African Americans accepted or resisted consumer culture. As a cursory analysis of consumption patterns in colonial New England, New York, and Wisconsin, in this chapter I have taken a similar tack. Rather than approaching these contexts in terms of acculturation or the preservation of untouched “Indianisms,” I attempt to move beyond the dichotomizing tropes (essences of Indian and European) that still lurk in archaeologies of colonial North America. Brothertown consumption practices blurred boundaries between Indian and white and fostered new and likely unforeseen conceptions of personhood and individuality by way of shifts in long-term memory practices within the community. However, the changes also played a key role in maintaining intracommunal relations—in some ways portraying the boundary between insiders and outsiders as much more diffuse than in previous decades. These new representations aided the Brothertown community in its quest for citizenship and land rights.

The consumption of text-bearing gravestones also tied to Christianity, a central unifying force for the community since the eighteenth century. As evinced by Belva Mosher’s diary entries, the Methodist church in Brothertown, Wisconsin, remained at the figurative center of the community in the early twentieth century. Perhaps Belva envisioned wearing her new silk taffeta skirt to communal events such as church meetings, dances, and other occasions at the Brothertown ballroom (figure 2.2), which she mentions frequently in her diary. She may have worn the skirt to the Brothertown Homecoming, an annual summer event for which Brothertown Indians from far away come back to Brothertown, Wisconsin, to reconnect with family and friends. Of note, Belva’s diary contains the earliest written mention of the event (Mosher 1917–1923), which still takes place today.

Figure 2.2. Brothertown ballroom, Brothertown, Wisconsin. Photo from the author’s collection, courtesy of the Brothertown Indian Nation.

Consumption practices offer new slants on changing communal structures, including both continuities and changes in materiality, cultural traditions, and community relations. This brief summary of indigenous consumption speaks also to contemporary debates and struggles over indigenous sovereignty and identity (Hayes and Cipolla, this volume; Mrozowski, Gould, and Law Pezzarossi, this volume). Following recent calls in archaeology to address contemporary social issues in Native North America (Cipolla 2011, 2013a; Lightfoot et al. 2013; Mrozowski et al. 2009), I contend that the complexities of colonial interaction and endurance provide an important critique of the federal recognition process in the United States. As Kent Lightfoot and his colleagues (2013) point out, far too little attention has been paid to the ways in which indigenous societies shaped colonial developments in North America (how these broader processes were localized). Casting away simplistic narratives of cultural loss, Lightfoot and his colleagues (2013:99) argue that archaeologies of colonialism provide “ideal frameworks for evaluating what happened to specific tribal groups as they dealt with various colonial programs in a long-term perspective.”

Rather than ending the colonial narrative with Pequot and Brothertown adoptions of foreign house styles, ceramics, and grave markers, I have attempted to extrapolate the reasons behind certain sequences of material change. Some of these practices related to deeper traditions of commemoration and symbolism despite their overtly “Europeanized” appearance in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Tracking the changes in consumption from the eighteenth century to the present also sheds light on the long-term outcomes of certain cultural transformations. By linking consumer goods like Belva Mosher’s skirt and Samson Occom’s grave marker to internal social dynamics, new light is cast on the ways in which indigenous communities made their places in—and survived—the modern world. Yet, similar to the findings of Lightfoot et al. (2013), in this study I show the inequities of the federal recognition process. By asking tribal groups to demonstrate that they maintained communal ties, political structures, and identities in only one way and with only one result, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) has set many indigenous communities up for failure. This is evident in the BIA’s recent negative ruling on the Brothertown Indians’ petition for tribal sovereignty (Cipolla 2011, 2013a, 2013b). By bringing examples of colonial consumption into dialogue with more ancient cases, this chapter helps to demonstrate the complexities of colonial entanglement, highlighting the role that archaeology could play in reshaping the world in which we live.

References Cited

Bross, Kristina, and Hilary E. Wyss

2008Introduction. In Early Native Literacies in New England: A Documentary and Critical Anthology, edited by Kristina Bross and Hilary E. Wyss, pp. 1–14. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

Brothertown Indians

1788–1810, 1901 Brothertown Records. Manuscript on file, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison.

Cipolla, Craig N.

2005Negotiating Boundaries of Colonialism: Nineteenth-Century Lifeways on the Eastern Pequot Reservation, North Stonington, Connecticut. Unpublished master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts Boston.

2008Signs of Identity, Signs of Memory. Archaeological Dialogues 15(2):196–215.

2011Commemoration, Community, and Colonial Politics at Brothertown. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 36(2):145–172.

2012aPeopling the Place, “Placing” the People: An Archaeology of Brothertown Discourse. Ethnohistory 59(1):51–78.

2012bTextual Artifacts, Artifactual Texts: An Historical Archaeology of Brothertown Writing. Historical Archaeology 46(2):91–109.

2013aBecoming Brothertown: Native American Ethnogenesis and Endurance in the Modern World. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

2013bNative American Historical Archaeology and the Trope of Authenticity. Historical Archaeology 47(3):12–22.

Cipolla, Craig N., and Kevin A. McBride

2014Globalizing the Local and Localizing the Global at Mashantucket. Paper presented at the 79th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Austin.

Cipolla, Craig N., Stephen W. Silliman, and David B. Landon

2007‘Making Do’: Nineteenth-Century Subsistence Practices on the Eastern Pequot Reservation. Northeast Anthropology 74:41–64.

Cogley, Richard W.

1999John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Crosby, Constance A.

1988From Myth to History, or Why King Philip’s Ghost Walks Abroad. In The Recovery of Meaning: Historical Archaeology in the Eastern United States, edited by Mark P. Leone and Parker B. Potter, pp. 183–210. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

DeForest, John W.

1964 [1851] History of the Indians of Connecticut: From the Earliest Known Period to 1850. Shoe String Press, Hamden, Connecticut.

Den Ouden, Amy

2005Beyond Conquest: Native Peoples, Reservation Land, and the Struggle for History. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Dietler, Michael

2010Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Douglas, Mary, and Baron Isherwood

1979The World of Goods: Toward an Anthropology of Consumption. Norton, New York.

Ferris, Neal

2009The Archaeology of Native-Lived Colonialism: Challenging History in the Great Lakes. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Fish, Joseph

1983Old Light on Separate Ways: The Narragansett Diary of Joseph Fish 1765–1776, edited by William S. Simmons and Cheryl L. Simmons. University Press of New England, Providence, Rhode Island.

Fowles, Severin M.

2013An Archaeology of Doings: Secularism and the Study of Pueblo Religion. School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe.

Gibson, Susan G. (editor)

1980Burr’s Hill, a 17th Century Wampanoag Burial Ground in Warren, Rhode Island. Brown University Press, Providence.

Hayden, Anna K.

2012Household Spaces: 18th- and 19th-Century Spatial Practices on the Eastern Pequot Reservation. Unpublished master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts Boston.

James, Simon

2011Rome and the Sword: How Warriors and Weapons Shaped Roman History. Thames and Hudson, New York.

Jarvis, Brad

2010The Brothertown Nation of Indians: Land Ownership and Nationalism in Early America, 1740–1840. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Latour, Bruno

2005Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

Lightfoot, Kent G., Lee M. Panich, Tsim D. Schneider, Sara L. Gonzalez, Mathew A. Russell, Darren Modzelewski, Theresa Molino, and Elliot H. Blair

2013The Study of Indigenous Political Economies and Colonialism: Implications for Contemporary Tribal Groups and Federal Recognition. American Antiquity 78(1):89–103.

Love, William D.

1899Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, New York.

McBride, Kevin

1990The Historical Archaeology of the Mashantucket Pequot. In The Pequots: The Fall and Rise of an American Indian Nation, edited by Laurence M. Hauptman and James D. Wherry, pp. 96–116. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Miller, Christopher L., and George R. Hamell

1986A New Perspective on Indian-White Contact: Cultural Symbols and Colonial Trade. Journal of American History 73(2):311–328.

Miller, Daniel

1987Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Blackwell, New York.

Miller, Daniel (editor)

1995Acknowledging Consumption: A Review of New Studies. Routledge, New York.

Morgan, Lewis H.

1962 [1851] League of the Iroquois. Citadel Press, Secaucus, New Jersey.

Mosher, Belva

1917–1923 Diary. Manuscript on file, Brothertown Indian Nation Archive, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

Mrozowski, Stephen A., Holly Herbster, David Brown, and Katherine L. Priddy

2009Magunkaquog Materiality, Federal Recognition, and the Search for a Deeper History. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13(4):430–463.

Mullins, Paul

2004Ideology, Power, and Capitalism: The Historical Archaeology of Consumption. In A Companion to Social Archaeology, edited by Lynn Meskell and Robert W. Preucel, pp. 195–211. Blackwell, Malden, Massachusetts.

2011The Archaeology of Consumption. Annual Review of Anthropology 40:133–144.

O’Brien, Jean M.

1997Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rubertone, Patricia E.

2000The Historical Archaeology of Native Americans. Annual Review of Anthropology 29:425–446.

2001Grave Undertakings: An Archaeology of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Salisbury, Neal

1974Red Puritans: The “Praying Indians” of Massachusetts Bay and John Eliot. William and Mary Quarterly 31(1):27–54.

Scheiber, Laura L., and Mark D. Mitchell (editors)

2010Across a Great Divide: Continuity and Change in Native North American Societies, 1400–1900. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Silliman, Stephen W.

2005Culture Contact or Colonialism? Challenges in the Archaeology of Native North America. American Antiquity 70 (1):55–74.

2009Change and Continuity, Practice and Memory: Native American Persistence in Colonial New England. American Antiquity, 74(2):211–230.

Silliman, Stephen W., and Thomas A. Witt

2010The Complexities of Consumption: Eastern Pequot Cultural Economics in 18th-Century Colonial New England. Historical Archaeology 44(4):46–68.

Silverman, David J.

2010Red Brethren: The Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians and the Problem of Race in Early America. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Simmons, William S.

1970Cautantowwit’s House: An Indian Burial Ground on the Island of Conanicut in Narragansett Bay. Brown University Press, Providence, Rhode Island.

Sturtevant, William C.

1975Two 1761 Wigwams at Niantic. American Antiquity 40(4):437–444.

White, Richard

1991The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. University of Cambridge Press, Cambridge, England.

Williams, Rodger

1973 [1643] A Key into the Language of America, edited by J. J. Teunissen and E. J. Hinz. Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan.

Witt, Thomas A.

2007Negotiating Colonial Markets: The Navigation of 18th-Century Colonial Economies by the Eastern Pequot. Unpublished master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts Boston.