4

Indigeneity and Diaspora

Colonialism and the Classification of Displacement

KATHERINE H. HAYES

It is difficult to avoid using some kind of label when we attempt to interpret the experience of colonial subjects of the past despite our understanding that contemporary subject positions are the product, not precursor, of historical processes. In the United States, very often those labels are racialized; all the more so when we assume that racial tensions have their roots in the earliest colonial days of slavery. Certainly in the rhetoric of the colonists who wrote of enslaved Africans and Native Americans, the differences—in social status, physical appearance, and cultural practice—were stark. But in circumstances in which Native people and Africans, whom colonists saw as so clearly different, had the common role of laborer, must we assume that the differences the colonists saw (their emergent categories of race) were shared by all? In certain plantation contexts it is indeed exceedingly difficult to archaeologically distinguish enslaved African spaces and practices from those of Native Americans, precisely because they were doing much the same things in the same places. Yet Africans and Indians were also not the same. Each arrived at plantations via rather different routes and histories, and those differences might be best captured in the alternative frameworks of “diaspora” and “indigeneity.” What are the implications of using these terms in historical contexts?

Both of these terms have multiple valences. Though they may be thought of as essentially geographic referents, their emergences in archaeology derive also from politically specific conditions. Archaeologies of African America have been well established since the 1980s, arising from the era of civil rights movements, while the study of colonial-period Native Americans through archaeology took off from the historical consciousness of the Columbian quincentenary and the political consciousness of NAGPRA in the 1990s. In general, each is treated as a distinct subject of study, although many historians and archaeologists have acknowledged that their social spheres were not mutually exclusive. This distinction may be a product of the way we approach colonialism in our research. Colonialism is a process in which colonizing or settling populations exploit local resources, especially land and labor, but critically also impose new systems of social and economic order. In the United States it might be said that the former exploitation is largely yet not entirely in the past, but the latter—the imposition of social and economic orders—are sites of ongoing colonialism. In historical archaeology we have tended to focus our attention on the former process. Native Americans and African Americans are treated as separately oppressed groups, polarizing their experiences along lines like land removal versus labor exploitation; forcible transport to the Americas versus forcible displacement from American homelands; decreasing population versus increasing; and the contemporary categorization of descendant communities as diasporic versus indigenous. Although we recognize the inescapable contemporary political and social environment in which we interpret historical experiences (the environment in which indigenous and diasporic identity is most meaningful), still it is the historical experience that our evidence is taken to derive from—and we should strive to recognize how we have read those historical circumstances through the lenses of their longer-term outcomes (Leone 1982) rather than their immediate uncertainty.

Without dismissing the quite different historical points of entry and contemporary political priorities for Native and black communities, I question why we do not see more research in the intersection of the two in the study of colonialism. In this chapter I explore two main lines of speculation on this question: first, to think through current definitions of “indigeneity” and “diaspora”; and second, to argue that a comparative perspective highlights a significant distinction between the manner in which diasporic and indigenous communities imagined their political locations and futures. These geographic and political imaginaries are reduced and ignored when the terms are simply used as glosses for racialized or otherwise essentialized groups, something that occurs when we assume a kind of historical inevitability (Kenrick 2011). I compare two archaeological case studies throughout to speculate not just on how the past and memory informed the colonial encounter but also on how historical agents imagined and acted on ideas of what the future would bring.

From Opposite Sides of the Algonquian World

A comparison of two rather different sites of colonial entanglement from the eastern and western margins of the Algonquian world demonstrates how shared concepts of social inclusion yet radically different experiences of colonization play into colonial outcomes (map 4.1). In the east, European colonization proceeded at a fairly rapid pace where British colonies sought land for long-term settlement and the Dutch colony of New Netherland, though more interested in engaging in trade, was ultimately taken over by the British by 1674 (Siminoff 2004). In the west, the French colonizers struggled in their efforts to establish long-term settlement and were most successful in accessing the interior only through local trade partners, many of whom were Anishinaabe people migrating in that direction due to pressure from the eastern British colonies (White 1991).

For the northeast colonies, there is a popular narrative of the colonial era that has suppressed the consideration of indigeneity and diaspora: that due to the disappearance of Indian people and the lack of slavery, the colonies were quite socially homogeneous (Melish 1998; O’Brien 2010). Neither of these conditions was the case, and the site of Sylvester Manor is a prime counter example. This estate on Shelter Island, at the east end of Long Island in New York, was a provisioning plantation operated, per documentary evidence, by the labor of enslaved Africans. In initially approaching the interpretation of the site, the expectation was that difference according to black/white racialized identity would be evident, an approach that was confounded on two fronts. First, the plantation at Sylvester Manor was established in 1652, prior to the legal codification of slavery in racial categories (1674 at the earliest in New York). This is not to say that those categories were not already part of the colonists’ discourse, but they were inchoate. Second, the plantation laborers included not only the enslaved Africans as identified in wills and other documents but also Native Americans, based on the archaeological evidence of their technological traditions, skills, and iconographic representations. One such technological tradition identified was wampum production (figure 4.1), the manufacture of shell beads that served as a mainstay of coastal Algonquian tribute payments and as a standardized currency in both Dutch and English colonies. The structure of the plantation remains shows an intimately spaced core working and residential area and no evidence of separate spaces for laborers apart from the colonists or of one group of laborers from another (Hayes 2013; Mrozowski et al. 2007; Mrozowski, Hayes, and Hancock 2007).

Map 4.1. Eastern U.S. site areas: 1, Shelter Island, New York; 2, central Minnesota; Algonquian precolonial language areas, shaded in light gray. Map adapted by the author from “Algonquian langs.” Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Algonquian_langs.png#mediaviewer/File:Algonquian_langs.png.

Thus a shared heritage of enslavement—or at least plantation labor, as documentary remains do not record the status of the Indian laborers and only rarely acknowledge their presence in any capacity—appears to cut across the lines of race that our eyes have inherited. As some of the descendant communities in the region acknowledge, this shared heritage accompanies a history of intermarriage (for example, Boissevain 1956 on the Narragansetts’ refusal to reject tribal members with African ancestry), though given the implicit expectations for racial identity in federal recognition cases, such an admission is dangerous for tribes currently seeking recognition (McKinney 2006). Given this context, we need instead an approach that “decolonizes” our expectations for the kinds of affiliations and distinctions that arose on the plantation.

Figure 4.1. Wampum (shell beads) produced at Sylvester Manor plantation. Photo by Melody Henkel.

A contrasting colonial trajectory on the other side of the Algonquian world was first brought to my attention when engaging with the work of historian Michael Witgen (2012). A student of Richard White, Witgen recognized the contribution of White’s “middle ground” (1991) as a concept of creative misunderstanding in colonial contexts of mutual dependence in the Upper and Western Great Lakes (the pays d’en haut). In redescribing the early colonial encounters between French colonial authorities and the populous Native communities, however, Witgen insists that from the Native Anishinaabe perspective, the alliances with the vastly outnumbered French were only a small part of their own major reimagination of the political landscape. Reading through accounts of a 1660 Feast of the Dead written by Pierre Radisson, who claimed to have arranged the event as a means of declaring French authority through alliance, Witgen argues that instead the French presence was somewhat incidental to the efforts of the Anishinaabeg, who sought alliance with other Native political entities, the Cree and the Dakota, to construct a powerful network of trade and expand the territory of their hunting. Unlike in White’s historical reading, where the Anishinaabeg were viewed as refugees (a diaspora) pushed west by European settlement, Witgen posits that their alliance and kin network assured their access to place; in the Anishinaabe political world, rights are assured not in territory but in relations of either kin or enemy, categories that could and did shift over time (Bohaker 2006 offers a critique based in the role of kin groups). A refugee is a type of person who does not fit these categories. Neither, for that matter, do identifications like diasporic or indigenous. So what do these terms do analytically or politically today that we think to assign them to the past?

Defining Diaspora

If one were asked to provide the most immediate association of diaspora, likely the response would be of a dispersed population retaining cultural associations with and memories of a homeland to which they cannot return due to traumatic dislocation. Clifford (1997), in his oft-cited discussions of diaspora, notes that this forms the basis of Safran’s foundational contribution (1991). But Clifford urges us to introduce flexibility to this definition because of the boundary conditions the term implies. He notes, for example, that diaspora is often problematically defined in opposition to both nation-states and indigeneity (1997:250); to this I would add that diaspora, in the polarization of homeland and dispersal, draws attention to the originary rupture, precluding a more emergent or temporally fluid sense of diasporic identity.

The concept of diaspora has been a very productive framework for addressing enslaved Africans and African Americans. The nature of their dislocation and ongoing experience was certainly traumatic, their numbers were dispersed widely, and subsequent generations were barred from return. As neither essentialized identity nor an absolute rupture from culture and history, the diaspora concept allows us to explore the self-conscious reference and reproduction of a distinctive identity among the enslaved and their descendants. Archaeologists have well demonstrated the retention of certain cultural ties or memories through material and ritual practices, even as these retentions were reshaped under the conditions of enslavement (among them Fennell 2007; Franklin 2001; Heath and Bennett 2000; Wilkie and Farnsworth 2005). Historians of American slavery also have written eloquently about the self-conscious associations to Africa that enslaved and later free African American communities evoked as a form of survivance (Gomez 1998; Hall 2005; Horton and Horton 1979; Wilder 2005).

But Paul Gilroy (1991, 1993) and other cultural critics have pointed out that the location of diasporic African identity for many descendant communities has shifted away from Africa and more to the shared histories of enslavement and marginalization (prompting his use of the term “Black Atlantic”). How can a diasporic community remain so without reference to a homeland? Indeed, such a reference retains a form of opposition to nation-states—not purely American, but distinguished as African or black Americans. Gilroy argues emphatically against the static national or racial locations of diaspora and instead for transnationalism, culture located in transition and travel. Homeland is, to some extent, turned inward by a creative response to dislocation; as Barbara Bender (2001:78) has noted, “Dislocation is always also relocation.” Creative relocation is a theme that has been explored by archaeologists, for example in situating the experience of slavery in broader landscapes rather than singular sites (McKee 1992). This was likely the case at Sylvester Manor. We need not only consider the relocation of enslaved Africans into the core plantation, tightly controlled by the Sylvester family, for livestock, field, and orchard work would have brought them to landscapes little seen or controlled (Trigg and Landon 2010), perhaps even seen as an Indian landscape.

Clifford further explored the implied opposition of diaspora to indigeneity. Citing historical American Indian displacements and removals as well as contemporary migrations to and from reservation lands, he has noted that it seemed reasonable to speak of diasporic identity for “tribal peoples” (1997:253). In fact, these communities may most strongly identify with the original definitions of diaspora. Ironically, in making these distinctions Clifford also notes the specific legal contexts prompting his use of the term “tribal” rather than “indigenous” in which Indian land claims came to be judged based on historical continuity. “Tribe” is a term, like “continuity,” that he felt connoted rootedness rather than movement, which is implied in both “diaspora” and the anthropological term “band.” We see an ambiguous conflation of social structure (tribes and bands) with place in the context of Indian claims occurring in the aftermath of countless historical removals.

Finally we might think of diaspora’s location in experience and history rather than in place. Lilley (2006) has suggested viewing both indigenous and settler Australians as diasporic to draw attention to how each descendant group has located its identity to some extent in colonial oppression. Arguably such an approach carries a desire to avoid questions of origin, equating very different kinds of claims with one another and undercutting the position of indigenous polities in particular. On the other hand, from the perspective of vindicationist scholars, diasporan subjectivity directly challenges the essentialism of racial identity while still retaining shared history and heritage as a basis for defining community (Mullins 2008). Thus while diaspora might in a very basic way be defined by dislocation and movement, it must be more to set it apart from the dislocations and movements that occur on a common and massive scale today (Bender 2001; Connerton 2009). The “more” becomes apparent when comparing diaspora to concepts of indigeneity.

Defining Indigeneity

If the concept of diaspora is a moving target (so to speak), “indigenous” is no simpler despite its metaphors of rootedness. The term is most often taken as simply a marker of local descent or origins, as with “autochthonous.” In this sense, often heard in Europe, “indigenous” might be defined in opposition to “immigrant” (Holtorf 2009); viewed in this fashion, indigenous identity has been regarded with the suspicion for claims to essentialism (Kuper 2003; also Gausset, Kenrick, and Gibb 2011; Kenrick and Lewis 2004). But when related to issues of heritage, colonialism, and sovereignty, indigeneity quickly becomes complex. In his 2005 broad review of indigenous perspectives on archaeology, Watkins notes the construction of indigeneity in relation to colonization, either historical or contemporary. The term may refer to a history of structural disenfranchisement or marginalization and the maintenance of political and cultural distinction within a surrounding nation. These definitions indicate that indigeneity is a political identity; American Indians, for example, are not minorities (another term often mapped onto “diaspora”) because they occupy a categorically different relationship with the federal government (Wilkins and Stark 2011). Thus indigeneity in the initial sense may be applied to historical communities as a way of distinguishing local from nonlocal; but in the latter sense it is best understood in contemporary Native communities, encompassing a deep historical relationship with settler states. Within this framework, indigeneity also carries connotations of vulnerability, imminent risk, or threat to survival (Harrison 2013:30–31). While such an approach does characterize many contemporary Native nations’ experience, it also carries the double bind in equating indigeneity with poverty or disadvantage. Does indigeneity disappear when economic stability is achieved (Cattelino 2010), or does history not play a continuing role in defining community as it does through diaspora?

Though these issues figure heavily in settler societies, they may be less laden in Africa. Writing about how to conceptualize indigenous archaeologies in Africa, Lane (2011) notes that indigeneity there has parallels to ethnicity in its boundary construction. For many contemporary African societies, Kenrick and Lewis note (2004:6), indigeneity is relative: “Africans view themselves as indigenous relative to colonial and post-colonial powers. Additionally, Africans who live in the same regions as African hunter-gatherers and former hunter-gatherers recognize these groups as being indigenous relative to themselves.” In this sense, indigenous identity is an act of critical geography, a situated assertion of what is native or foreign. It is by such acts that communities project the imagined political landscape, much in the same way that Witgen (2012) describes in the pays d’en haut of the Western Great Lakes. This, I would argue, is a valuable approach if we want to employ the concept of indigeneity in a way that is neither analytically oversimplified nor politically overdetermined. It also presses us to consider boundaries beyond those of nation-states that were still historically significant (Chang 2011).

This framework for indigeneity shares other parallels with the discourse of diaspora. For Clifford, in his “flexible” construction, “the term ‘diaspora’ is a signifier not simply of transnationality and movement but of political struggles to define the local, as distinctive community, in historical contexts of displacement” (1997:252). In the contemporary political moment, those struggles may be defined by recourse to the capitalized “Indigenous” identification given the international movements and legal structures that are emergent. But to address the local and distinctive communities in the past and their imagined futures, we have to situate them within the historically contingent conditions of colonialism as well as their shifting grounds over time. Colonialism in the United States (and other places) has become reliant upon a racialized episteme, one that consistently separates diaspora and indigeneity and brings them into conflict with one another. Were we to attend to imagined futures instead, we might be exploring the historical struggles over the concepts of citizenship and sovereignty and highlighting how those comprise, in large part, the shifting grounds of colonial discourse (Byrd 2011; Camp 2013).

Here I want to reiterate that I am not suggesting there is no substantive difference between diaspora and indigeneity or even that these concepts are only meaningful in contemporary political discourse. Often, however, these critical nuances are overlooked in scholars’ appropriation of the terms. For example, one of the characteristics of diaspora included in Safran’s foundational definition (1991:83–84) is that members are dispersed to two or more locations; in other words, community itself is dispersed as perhaps family units or individuals in the case of African enslavement. Indigenous communities, on the other hand, often have been displaced as communities. This difference parlays into routes to defining the local and the distinctive nature of the community as well as the recourse to structures of governance that may be maintained by communities but not by families or individuals. We might also think about ethnogenesis and community formation, which perhaps have their roots in diasporic peoples but occur in conditions that allow for the development of indigenous (local) governance and identity, as in the Brothertown Indian Nation (Cipolla 2013, this volume). Here we see a clear connection to discourse of citizenship and sovereignty.

Comparing Cases

Is there any way to mobilize these nuanced concepts of political and geographic imagination, however, in archaeological interpretations? It might be enough that the concepts remind us of the ongoing impacts of colonialism in the very categories we might otherwise uncritically apply to past communities. In that sense, we should avoid the use of these two terms as simple glosses for race or ethnicity. Of greater significance to the historic contexts themselves, indigenous and diasporic identities trace different ideas about the reproduction of communities within larger societies rather than reflecting static attachments to origin and tradition. As such we should see these ideas as evolving through time, in part because the conditions and structures of colonial society that manage alterity have also evolved constantly. These colonial structures include discourses of race, governance, human rights, manifest destiny, social contracts, and the idea of free market economy. Thus in identifying groups as indigenous and/or diasporic, we could look to what options might have been open to a community at the time that would enable it to exist within or separate from those colonial structures.

As noted earlier, the context of the French in the Western Great Lakes provides a tantalizing comparative perspective. To take the case which Witgen (2012) wrote of in the pays d’en haut, we would stop thinking about the fur trade in the western interior, far from the large colonial posts, as either directed by Euro-American traders or an equal “middle ground” between traders and the Native communities they traveled with. Instead, we would view the traders as subject to the conditions and political landscape of the Anishinaabeg, who were themselves engaged in expanding their territory and in effect staking a claim to local sovereignty. Fur-trade-related sites in Minnesota, along the western edge of the eastern woodlands, are quite ephemeral because of the short-term occupation by Anishinaabe hunters and their families as they moved through the territories they claimed either through alliance or warfare with Eastern Dakota people. This is true also of the traders who either lived as their local partners did or who established rare winter-only fortified posts that they dismantled or destroyed upon leaving (Birk 1991, 1999; Hayes 2011, 2014). Rather than take this ephemerality as a marker of the precarious balance of indigenous lifeways under colonial conditions, it may be seen as the precarious nature of Euro-American lifeways under indigenous conditions.

Life in this region was dictated by the political landscape of negotiation, the terms of which were not set by white traders. In other words, their success in this landscape was dependent upon being incorporated into the local; incorporation has recently been explored as a process of indigenous autonomy among seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Haudenosaunee (Jordan 2013). Two late-eighteenth-century fur-trade sites in central Minnesota, Little Round Hill (Hayes 2014) and the Réaume Post site, demonstrate the radical difference that such incorporation makes.1

Both sites are located within the greater Mississippi River watershed within ten miles of each other, dating to a period when the rivers were a major highway system facilitating the fur trade in this ecologically rich transition between woodland and plains. The region was periodically contested by Anishinaabe and Dakota peoples (Warren 1984 [1885]), each staking claims to the rich hunting grounds. Both sites were temporary (winter-only) base camps, archaeologically and in historical records identified as places of engagement between Anishinaabe hunters and trappers and Euro-Canadian traders exchanging food and furs for a variety of trade goods. The two sites were, however, captured in very different kinds of archival records, hinting at their positions within the political landscape.

While the trader Joseph Réaume was employed variously by established companies and referred to by his fellow traders in their journals and memoirs (Allard 2013), the trader at Little Round Hill is nowhere to be found in the same archive. Instead he is referred to in William Warren’s 1885 History of the Ojibway People, a compilation of oral histories collected by Warren, who was partly of Ojibway ancestry, spoke the language fluently, and made it his mission to record what must be considered indigenous historiography (MacLeod 1992; Warren 1984 [1885]). In Warren’s account, the trader at Little Round Hill was named in English only “a Blacksmith,” a translation of Ah-wish-to-yah, though he was identified as French and at one point as white. Likely an independent trader and possibly of mixed ancestry, Ah-wish-to-yah’s camp was also occupied by a few of his coureurs-du-bois and ten Pillager band hunters and their families (Warren 1984 [1885]:275–278). While Réaume does make an appearance in Warren’s account, traveling with the well-known trader Jean Baptiste Cadotte (280), his engagement warrants no further mention.

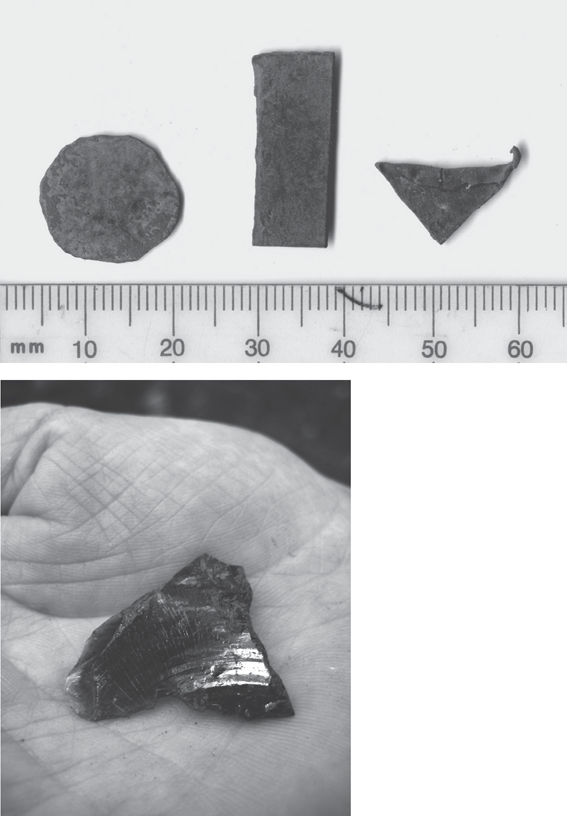

Caught in two different archives, from the perspective of the large fur-trade companies on the one hand and the perspective of Warren’s indigenous historians on the other, these two sites illustrate two quite different modes of dwelling on the landscape. Ah-wish-to-yah’s camp at Little Round Hill, though in a dangerous area and supposedly attacked by a band of Dakota warriors, resembles contemporaneous or earlier Anishinaabe or Dakota camps, with several semisubterranean structures, likely covered by light-framed superstructures, and central hearths. While the structures resembled one another, slight variations in associated artifacts suggest different occupants; for example, locally produced pottery was not found in all dwellings, and iron items were found only in one dwelling. Glass seed beads for embroidery were found in most dwellings, but many more were recovered in the activity areas between structures. The activity area was well-used; both lithic debris (including obsidian, a rare import from far west of Minnesota) and firearm fragments were found, along with fragments of reworked brass sheet fragments (figure 4.2). These items index participation in a multitude of trade networks. Faunal remains, evidence of past meals and of the business of the fur trade, were found across the site. Perhaps most telling, the camp was not protected by a stockade wall; its occupants likely regarded the features of the landscape, including the riverbanks themselves, as reliable defense. The occupants of this site appear, in their general lack of defensiveness, to have belonged there, perhaps assured by their place within a broader network of kin and allies despite the ethnic diversity we tend to assume was significant. It is an occupation at odds with the interpretive signage at the Little Round Hill site, depicting a somewhat idealized fur-trade post structure as a bastion in the wilderness (figure 4.3). In fact, the structures located in excavation most closely resemble the round dwellings meant to indicate Anishinaabe housing in the depiction.

Figure 4.2. Clipped and reworked brass items (above) and obsidian flake (left) recovered at the Little Round Hill site. Photos by the author.

Figure 4.3. Interpretive sign, including artist’s renditions, at the Little Round Hill site. The man depicted is Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe, also known as Flatmouth, the chief of the Pillager Leech Lake Ojibwe who related the site’s story. The stockade wall shown did not exist. The site is now on the National Register of Historic Places and located within Wadena County parkland. Photo by the author.

The Réaume Post site, on the other hand, appeared as a heavily fortified camp, carefully maintaining isolation behind sturdy stockade walls, timber structures, and substantial stone and daub chimneys, and more closely resembling the squared structures in the interpretive sign at Little Round Hill. Although a rather similar range of faunal remains and trade materials (particularly beads, copper or other metal adornments, iron implements, and firearms) were found within Réaume Post’s fortlike walls, no lithic debris or local pottery was found, suggesting that while Native trade partners may have come inside its walls, they likely were not living there. Faunal remains, though similar in species represented, appear to have been discarded in restricted areas, perhaps in an attempt to create a particular appearance for the post area. All of the wooden structures at the Réaume site were completely burned, though it may have occurred after the winter occupation was left behind. While Réaume may have been engaged in the trade, his post suggests that he was less engaged in the Native political landscape. I would suggest that he knew he was not in control of the arena in which he was operating; and though neither he nor other company traders had any interest in permanent settlement there, Réaume’s post indicates an insistence on separation that is not in evidence at Ah-wish-to-yah’s camp. In other words, each trader operated within a rather different construction of the local, Ah-wish-to-yah’s turned outward to the indigenous landscape and Réaume’s turned inward.

In the pays d’en haut we see an indigeneity negotiated not strictly in terms relative to colonists in a model of domination and resistance; the local was made by long-standing structures of kinship and alliance, not in reaction to colonists per se. Because the Native place was so created and European-descended traders were apparently willing to participate under these conditions (Sleeper-Smith 2001; White 1991), the future was anticipated through the ongoing negotiation of an alliance network. This perspective suggests a somewhat different way of looking at plantation contexts like Sylvester Manor and others where eastern Algonquian people were caught up in colonial enterprises.

Rather than viewing the rapid colonization and displacement of Native peoples in the Atlantic Northeast as a terminal narrative, we can focus on an ongoing renegotiation of their place in a much more complex network of belonging to secure a future. The Manhanset of Shelter Island in New York brought their complaints to the colonial court system when the Sylvesters and their financial partners began to build on the island in 1652. Though the details of the settlement are ambiguous, the case was resolved through what colonial authorities (and contemporary legal scholars) would regard as a quit claim, relinquishing control of the land to the Sylvesters. Archaeological excavations of the plantation subsequently built there show that the Manhanset did not leave the island, however, but rather were entangled in the plantation labor and production of wampum. Such a choice to stay might be regarded as acquiescence to the new colonial system. Instead I would suggest that the Manhanset saw the political landscape as still offering an indigenous system within which to work. They may have chosen to place themselves under the protection of the Sylvesters, yet still viewed their future as one of a sovereign community, in an understanding of political structure consistent with their earlier experiences with the Pequot or the Mohawk as tribute holders. A sovereign future is similarly acted upon by tribes today that petition for recognition and claim the right of historical self-representation (as described in Mrozowski, Gould, and Law Pezzarossi, this volume; and Hodge, Loren, and Capone, this volume).

By the same token, enslaved Africans may have regarded the Manhanset on the plantation as a potentially supportive network and possibly a means to create or maintain their own community. As noted earlier, the wider plantation landscape may have offered the opportunity to engage, to “relocate” as an emergent diaspora, or even to be incorporated into an Indian sovereign landscape. Such possibilities are difficult to imagine today because they require thinking past centuries of racial discourse. From the perspective of enslaved Africans in the seventeenth century, however, there was no reason to believe that one day their descendant generations would be pressed into mutually exclusive categories with quite different recourses to sovereignty (in-depth coverage of Sylvester Manor archaeology and history is presented in Hayes 2013 and in Hayes and Mrozowski 2007).

Conclusion

Diaspora and indigeneity are identifications that operate most apparently today but do indeed have significance for the way we approach the past. They are also subjectivities grounded in tracing a connection in past, present, and future. The African diaspora, as distinctive and local but simultaneously within a larger social structure, draws upon the past to push back against racialized structures in important ways. Diaspora today emphasizes the common historical background the community shares in defining itself in defiance of a neoliberal, “color-blind” rhetoric, while in the colonial past, we can imagine, it created the grounds for autonomy despite the system of racial slavery in which it existed. The African Burial Ground site in New York exemplifies both. The expression of diaspora in the past can be seen in the use of symbols of African origin on bodies or on coffins and in the apparent care taken by a community in committing the dead to their burials and maintaining the space itself for continued use (Perry, Howson, and Bianco 2006). In the recent past and present, the New York African diaspora community has pointed to a shared heritage of slavery to identify its right to be involved in the future of the rediscovered burial ground (Blakey 1998; LaRoche and Blakey 1997). In Brazil, maroon sites like Palmares have become places to locate a diverse heritage of diasporic cultural exchanges as well as slavery, a challenge to simple narratives of race and class as Ferreira and Funari (this volume) demonstrate. As Baker (1998) has described in his overview of anthropology’s evolving constructions of race, the Boasian contribution of culture as both not hierarchically comparable and historically particular has not been adopted in social policy in a balanced fashion, and references to diaspora can help to reappropriate the historically particular end of the formula.

I suppose, in a sense, the conclusion I draw from this extended musing over the terms “diaspora” and “indigeneity” is not so much that we should stop or radically reconsider our use of them. Indeed, in the examples just explored, a more nuanced consideration of how the terms intersect leads us potentially to new avenues and questions to pose of the archaeological contexts. Rather, it is that they incite us to introduce another level of temporality to the way we or other stakeholders portray past communities in the advent of colonization. We are accustomed to thinking about how the past (or tradition) has shaped our historical subjects’ way of living in the world and how colonialism was disruptive of that past. But I suggest we think also how their imagined political futures shaped their dwelling as well, even under conditions that were quite changed.

Note

1. Both sites were excavated by University of Minnesota archaeologists under the direction of the author from 2009 to 2013. This discussion is based on results reported in Hayes 2014 on Little Round Hill and preliminary analyses by Amélie Allard, whose dissertation on the Réaume site is in preparation as of this writing.

References Cited

Allard, Amélie

2013“Feeding the Crew: Foodways and Faunal Remains at Réaume’s Trading Post Site, Central Minnesota.” Paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Annual Meeting, January 9–12, Leicester, England.

Baker, Lee D.

1998From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896–1954. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Bender, Barbara

2001Landscapes on-the-Move. Journal of Social Archaeology 1(1):75–89.

Birk, Douglas

1991French Presence in Minnesota: The View from Site Mo20 near Little Falls. In French Colonial Archaeology: The Illinois Country and the Western Great Lakes, edited by John A. Walthall, pp. 237–266. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

1999The Archaeology of Sayer’s Fort: An 1804–1805 North West Company Wintering Quarters Site in East-Central Minnesota. Unpublished master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Minnesota Twin Cities.

Blakey, Michael L.

1998The New York African Burial Ground Project: An Examination of Enslaved Lives, A Construction of Ancestral Ties. Transforming Anthropology 7(1):53–58.

Bohaker, Heidi

2006“Nindoodemag”: The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600–1701. William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 63(1):23–52.

Boissevain, Ethel

1956The Detribalization of the Narragansett Indians: A Case Study. Ethnohistory 3(3):225–245.

Byrd, Jodi A.

2011The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Camp, Stacey Lynn

2013The Archaeology of Citizenship. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Cattelino, Jessica R.

2010The Double Bind of American Indian Need-Based Sovereignty. Cultural Anthropology 25(2):235–262.

Chang, David

2011Borderlands in a World at Sea: Concow Indians, Native Hawaiians, and South Chinese in Indigenous, Global, and National Spaces. Journal of American History 98:384–403.

Cipolla, Craig N.

2013Becoming Brothertown: Native American Ethnogenesis and Endurance in the Modern World. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Clifford, James

1997Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Connerton, Paul

2009How Modernity Forgets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Fennell, Christopher C.

2007Crossroads and Cosmologies: Diasporas and Ethnogenesis in the New World. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Franklin, Maria

2001The Archaeological Dimensions of Soul Food: Interpreting Race, Culture, and Afro-Virginian Identity. In Race and the Archaeology of Identity, edited by Charles E. Orser Jr., 88–107. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Gausset, Quentin, Justin Kenrick, and Robert Gibb

2011Indigeneity and Autochthony: A Couple of False Twins? Social Anthropology 19(2):135–142.

Gilroy, Paul

1991“There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack”: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

1993The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Gomez, Michael A.

1998Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo

2005Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Harrison, Rodney

2013Heritage: Critical Approaches. Routledge, London.

Hayes, Katherine

2011“Being Located in a Dangerous Neighborhood”: Investigating the Fur Trade in the Colonial Borderlands of Minnesota. Paper presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Austin, Texas, January 5–9.

2013Slavery Before Race: Europeans, Africans and Indians at Long Island’s Sylvester Manor Plantation, 1651–1884. New York University Press, New York.

2014Results of Survey and Excavation of the Little Round Hill (21WD16) and Cadotte Post (21WD17) Sites in Wadena County, Minnesota: A View of the Fur Trade in the Late Eighteenth Century. Report prepared for the Wadena County Historical Society and the Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office.

Hayes, Katherine, and Stephen Mrozowski (editors)

2007The Historical Archaeology of Sylvester Manor. Special issue, Northeast Historical Archaeology 36.

Heath, Barbara J., and Amber Bennett

2000“The Little Spots Allow’d Them”: The Archaeological Study of African-American Yards. Historical Archaeology 34(2):38–55.

Holtorf, Cornelius

2009A European Perspective on Indigenous and Immigrant Archaeologies. World Archaeology 41(4):672–681.

Horton, James Oliver, and Lois E. Horton

1979Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North. Holmes and Meier, New York.

Jordan, Kurt A.

2013Incorporation and Colonization: Post Columbian Iroquois Satellite Communities and Processes of Indigenous Autonomy. American Anthropologist 115(1):29–43.

Kenrick, Justin

2011Scottish Land Reform and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights: Self Determination and Historical Reversibility. Social Anthropology 19(2):189–203.

Kenrick, Justin, and Jerome Lewis

2004Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and the Politics of the Term “Indigenous.” Anthropology Today 20(2):4–9.

Kuper, Adam

2003The Return of the Native. Current Anthropology 44(3):389–402.

Lane, Paul

2011Possibilities for a Postcolonial Archaeology in Sub-Saharan Africa: Indigenous and Usable Pasts. World Archaeology 43(1):7–25.

LaRoche, Cheryl J., and Michael L. Blakey

1997Seizing Intellectual Power: The Dialogue at the New York African Burial Ground. Historical Archaeology 31(3):84–106.

Leone, Mark P.

1982Some Opinions about Recovering Mind. American Antiquity 47(4):742–760.

Lilley, Ian

2006Archaeology, Diaspora, and Decolonization. Journal of Social Archaeology 6(1):28–47.

MacLeod, D. Peter

1992The Anishinabeg Point of View: The History of the Great Lakes Region to 1800 in Nineteenth-Century Mississauga, Odawa, and Ojibwa Historiography. Canadian Historical Review 72(2):194–210.

McKee, Larry

1992The Ideals and Realities behind the Design and Use of 19th Century Virginia Slave Cabins. In The Art and Mystery of Historical Archaeology: Essays in Honor of James Deetz, edited by Anne Elizabeth Yentsch and Mary C. Beaudry, 195–213. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

McKinney, Tiffany M.

2006Race and Federal Recognition in Native New England. In Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country, edited by Tiya Miles and Sharon P. Holland, 57–79. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

Melish, Joanne Pope

1998Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Mrozowski, Stephen A., Katherine Hayes, and Anne P. Hancock

2007The Archaeology of Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36:1–15.

Mrozowski, Stephen A., Katherine Hayes, Heather Trigg, Jack Gary, David Landon, and Dennis Piechota

2007Conclusion: Meditations on the Archaeology of a Northern Plantation. Special issue, Northeast Historical Archaeology 36:143–156.

Mullins, Paul R.

2008Excavating America’s Metaphor: Race, Diaspora, and Vindicationist Archaeologies. Historical Archaeology 42(2):104–122.

O’Brien, Jean

2010Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Perry, Warren R., Jean Howson, and Barbara A. Bianco (editors)

2006New York African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report. Vol. I. Report prepared by Howard University, Washington, D.C., for the U.S. General Services Administration Northeastern and Caribbean Region.

Safran, William

1991Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return. Diaspora 1(1):83–99.

Siminoff, Faren R.

2004Crossing the Sound: The Rise of Atlantic American Communities in Seventeenth-Century Eastern Long Island. New York University Press, New York.

Sleeper-Smith, Susan

2001Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

Trigg, Heather B., and David B. Landon

2010Labor and Agricultural Production at Sylvester Manor Plantation, Shelter Island, New York. Historical Archaeology 44(3):36–53.

Warren, William W.

1984 [1885] History of the Ojibway People. Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul.

Watkins, Joe

2005Through Wary Eyes: Indigenous Perspectives on Archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 34:429–449.

White, Richard

1991The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Wilder, Craig Steven

2005Black Life in Freedom: Creating a Civic Culture. In Slavery in New York, edited by Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris, 215–237. New Press, New York.

Wilkie, Laurie A., and Paul Farnsworth

2005Sampling Many Pots: An Archaeology of Memory and Tradition at a Bahamian Plantation. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Wilkins, David E., and Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark

2011American Indian Politics and the American Political System. 3rd edition. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland.

Witgen, Michael

2012An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.