All roads may lead to Rome, but for much of recorded history all sea lanes have led to Sicily. The island’s position, strategically sited in the middle of the Mediterranean, has been both the proverbial curse and a blessing. Sicilians haven’t enjoyed too many centuries of peace, but the various powers that coveted and ruled their island over the centuries left behind a heady mix of cultures and riches.

The Greeks, Romans and Carthaginians turned the island into one of the great battlefields of ancient times; the Normans routed the Saracens, and the Spanish stepped in to replace the French.

The Phoenicians

Ever since the Phoenicians began pulling ashore, sometime around the 8th century BC, many of the powers of the Mediterranean and European world have fought for a stake in Sicily.

The Phoenicians left a remarkable settlement, Mozia, on the little island of San Pantaleo, off the western coast while Sicily’s Ancient Greek cities, especially those at Siracusa, Agrigento, Selinunte and Segesta, provide us with some of the best-preserved architectural remnants to come down from the classical age. The sumptuous mosaics at Casale are just some of the many remains of the Romans, who were here until the last days of the Empire; and the Cappella Palatina in Palermo as well as the cathedral at Monreale show off the considerable achievements of the Normans, who came to Sicily from the lands of northern France. The Castello Ursino in Catania is an example of the fortifications required to defend a foothold in Sicily during the Middle Ages.

Early settlers

Long before these empires began to establish strongholds in Sicily, Paleolithic and Neolithic peoples were occupying settlements scattered across the island. By the 10th century BC, a tribe known as the Sicili had migrated from mainland Italy to Sicily, giving the island its name. The Sicili settled in the east; the Sicani, from North Africa, and the Elymians, thought to have descended from the Trojans, established themselves in the west.

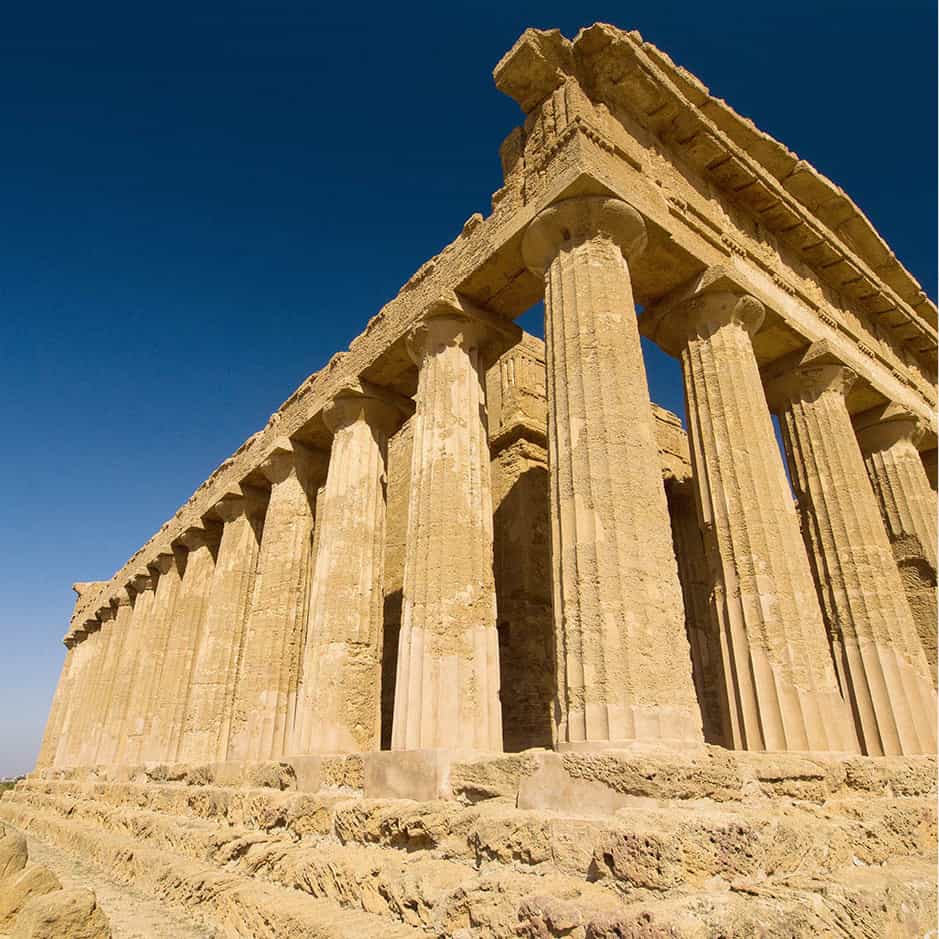

Sometime around the 8th century BC, Phoenicians sailed from the shores of the eastern Mediterranean to establish outposts at Mozia and elsewhere in Sicily. The Greeks, who would eventually overpower all these cultures, began arriving about the same time. Most of the Greek settlers came in search of land to farm, and Sicily offered vast tracts of fertile soil and ideal growing conditions. From colonies in Siracusa and elsewhere along the east coast, the Greeks spread across the island, establishing colonies at Gela, Agrigento and Selinunte. Agrigento, known to the ancients as Akragras, became especially powerful, and enough is left of this city on the southern coast to suggest the extent of its wealth. However, Siracusa soon became the supreme power on Sicily.

Temple of Concord, Valley of the Temples

Neil Buchan-Grant/Apa Publications

The Greek centuries

In 480 BC, the armies of the various Greek colonies joined forces under Gelon, the tyrannical ruler of Siracusa, to defeat the Carthaginians at Himera, on Sicily’s northern coast. The Greek victory ensured the supremacy of Siracusa in the affairs of Sicily until the city fell to the Romans some 250 years later. The victory also assured that Sicily would become a major Greek power in the Mediterranean; in fact, Sicily and the southern Italian mainland became known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) and had a larger Greek population than Greece itself.

Greek tyrants

Although in general usage the word ‘tyrant’ implies someone oppressive and cruel, in the Ancient world the word existed more as a title which declared a man to be the absolute ruler of a Greek colony, and probably someone who had seized power – not unlike today’s dictators. Some tyrants, like Theron, father-in-law of Gelon of Siracusa, were considered wise and fair.

Greek dominance, however, didn’t bring an end to warfare. The colonies often fought among themselves. Segesta, an Athenian satellite on the northwestern coast, was almost continually at war with Selinunte, an ally of Siracusa on the southern coast. Athens was alarmed by the ambitions of Siracusa and saw an opportunity to attack when Segesta asked for help in repelling the attacks from Selinunte. Athens assembled a massive fleet and sailed to Sicily in 415 BC; but the so-called Great Expedition ended in a humiliating defeat for the Athenians. The Siracusans imprisoned some 7,000 Athenian soldiers and put them to work in its limestone quarries, the Latomie.

Carthage, the colony the Phoenicians settled on the north shore of Africa near modern-day Tunis, wasn’t as easy to quell. The Carthaginian general Hannibal attacked Selinunte, Agrigento and other Sicilian cities. Siracusa’s tyrannical ruler, Dionysius I, retaliated in 397 BC by levelling Mozia, the Carthaginian stronghold on the island. Under Agathocles, Sicilian troops crossed the Mediterranean and attacked the Carthaginians on their own turf.

In the 3rd century BC, Sicily became the battleground of the Punic Wars that broke out between Rome and Carthage. When Siracusa sided with the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War, Rome sacked the city in 211 BC and took control of the island. The Roman Empire continued to control Sicily for the next seven centuries.

Detail of Triumph of Death fresco at Palazzo Abatellis

Neil Buchan-Grant/Apa Publications

Romans and Saracens

For Rome, Sicily was one vast wheat field, supplying the Empire with grain. For the most part Roman rule brought a commodity that until then was unknown in Sicily – peace, as well as the amphitheatres, baths and other Roman structures that still stand around the island.

Christianity arrived in Sicily around AD 200, and Siracusa became one of the most fervent early Christian strongholds in the Mediterranean, thousands of Siracusans worshipping and burying their dead in catacombs beneath the city until the Emperor Constantine lifted the prohibition against Christians a century later. Not long after Rome fell to the Visigoths in 410, Sicily became prey to Vandals and Ostrogoths who sacked the coasts. By 535 the island had fallen into the hands of the Byzantines; Siracusa was capital of the Eastern Byzantine Empire for five years, from 663 to 668.

The next wave of invasion came from North Africa. The island of Pantelleria, where an Arabic influence is still much in evidence, fell first in 700. It wasn’t until the 9th century that the assault began in force. After decades of fighting, the so-called Saracens – including Arabs, Spanish Muslims and Berbers – took Palermo in 831 and Siracusa in 878. Arab rule ushered in another golden age for Sicily. Palermo became one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world, comparable to Constantinople and Baghdad. The Muslim rulers revitalised the countryside, building irrigation systems and introducing oranges and lemons to the landscape.

Once again, the prosperity of Sicily proved to be irresistible to other powers. This time it was a Norman lord, Roger de Hauteville, who set his sights on the island and took Messina in 1061. All of Sicily was under Norman rule by 1091, with Palermo as its capital and Roger as its ruler. Rather than impose a foreign yoke on the island, Roger accommodated the island’s rich Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Roman heritage – Norman art and architecture, so richly preserved in the Norman churches in Palermo, Monreale and Cefalù, displays this fusion. When Roger’s son was crowned Roger II, King of Sicily, in 1130, his holdings included Sicily and most of southern Italy and his court was one of the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan in the world.

Masters of a Sicilian Style

While the achievements of Greeks and Normans are often what capture a visitor’s attention, Sicilian artists have made considerable contributions of their own – several artists developed a distinctly Sicilian style in their work. You will encounter them frequently around the island.

Domenico Gagini (1448–1492) came to Palermo in 1458 and spent the rest of his life gracing churches with his elegant Madonnas and other sculptures; his son, Antonello (1478–1536), carried on the tradition by becoming Sicily’s foremost sculptor of the Renaissance. You will find their work in numerous churches and in Palermo’s Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, where a room is filled with Gagini masterpieces.

Rosario Gagliardi (1700–1770) is the architect who created many of the Baroque churches and public buildings that transform towns like Noto and Ragusa into stage sets. The church of San Giorgio in Ragusa is a fine example of his mastery of this whimsical style.

Antonello da Messina (1430–1479) combined a mastery of light and spatial depth to create such masterpieces as his Portrait of an Unknown Man, now in the Museo Mandralisca in Cefalù.

Giacomo Serpotta (1656–1732) perfected the art of stucco work, or moulded plaster. His creations, which adorn the Oratorio del Rosario di San Domenico and other oratorios in Palermo, cover the walls with delicate religious imagery.

Castle in Erice

Neil Buchan-Grant/Apa Publications

Stupor Mundi and the Sicilian Vespers

A descendant, Frederick II von Hohenstaufen, was to carry on the Norman tradition of enlightened rule when he took the crown in 1220. His mother was Catherine, Roger II’s daughter, and his father was Henry VI of Swabia; this heritage gave him control of Sicily, much of Italy and parts of Germany. He introduced a unified legal system, promoted the arts and sciences and encouraged a blending of Islamic, Jewish and Christian cultures. Frederick ruled for more than 40 years and became known as Stupor Mundi, the Wonder of the World.

Frederick’s death once again left Sicily up for grabs. Among the contenders was the Papacy under Pope Urban IV, eager to get control of the lands of southern Italy. Backed by the Pope, Charles of Anjou, brother of the French King Saint Louis (Louis IX), defeated the Hohenstaufen supporters in a series of battles and became King of Sicily and Naples in 1268. Determined to punish Sicily for its loyalty to the Hohenstaufens, Charles imposed heavy taxes and confiscated lands.

An uprising against French rule broke out in Palermo on 30 March 1282; the first shots rang out at the hour the bells of the church of Santo Spirito rang for Vespers, and the revolt has come to be known as the Sicilian Vespers. Some scholars claim that it was instigated by the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII, who had learned that Charles was plotting to attack Constantinople and wrest control of Byzantine lands, and wished to divert the French by keeping them busy in Sicily. The immediate cause was an incident in which a French soldier stopped a Sicilian bride on her way to church and searched her for concealed weapons. An angry crowd killed the soldier immediately, and within days the citizenry had slaughtered more than 8,000 French troops across the island.

King Peter III of Aragón (whose wife, Constance, was a Hohenstaufen) arrived in a flotilla five months later, and the Sicilian nobles offered the Spaniard the throne. The Angevins and the Aragonese skirmished for control of the island for the next 20 years, and in the end Sicily belonged to the Spanish – and would remain in their hands for the next 400 years.

Puppet shows in Sicily date back centuries

Neil Buchan-Grant/Apa Publications

Spanish rule

Sicily became more or less a backwater when the European powers directed their expansionist ambitions to the New World. This inattention ensured that Sicily enjoyed one of the few periods of long peace in its history. In the absence of human drama, nature stepped in. The plague, brought to Sicily by the ships that called at its harbours, broke out repeatedly and decimated large portions of the population.

The end of the 17th century was especially calamitous. Mount Etna erupted in 1669 and sent molten lava flowing through the streets of Catania. An earthquake in 1693, also centred in the east, was even more destructive and took an enormous toll on human life. Sicilians rebuilt Noto and other cities in a distinctive style, the Sicilian Baroque.

The Treaty of Utrecht divided Spanish holdings, and in the early 18th century Sicily once again became a pawn of foreign powers. The island passed from the Italian House of Savoy to the Austrians and, in 1734, back to the Spanish, this time to the Bourbons. The British convinced the Bourbon king Ferdinand I to introduce a constitution, but he soon repealed it and called in Austrian mercenaries when citizens took to the streets of Palermo and other cities calling for independence; his successor, Ferdinand II, bombarded Messina in 1848 to quell an uprising for independence there.

Origins of the Mafia

The Mafia took root in Sicily in the 1860s, ostensibly to help the rural poor have their share of the land reform and other benefits that were to accompany freedom from rule. In effect, the Mafia became an integral part of the island’s power structure, controlling business and the workings of government, and today is said to ensure that Sicily remains a centre for drug trafficking.

From unification into the present

This unrest set the stage for Giuseppe Garibaldi, leader of the Risorgimento, the campaign for the unification of Italy. He sailed into Marsala on 11 May 1860 with his so-called Thousand, a reference to the guerrilla army that accompanied him. Garibaldi’s soldiers and Sicilian partisans were soon fighting in Palermo, and the island was free of Bourbon rule within a year. Sicilians were soon disillusioned – widespread poverty and government repression made life as part of a unified Italy more difficult than it had been under the Bourbons.

For many Sicilians, the only escape from impoverishment was emigration. By 1914, more than a million and a half Sicilians had left the island, usually for North and South America. The reforms introduced later by Mussolini and his fascist government did little to alleviate poverty, illiteracy and unemployment in Sicily.

The island once again became a battleground in World War II. In July 1943, the Allies made their first European landings at Gela on the southern coast while British and Canadian forces tackled the east coast. Allied bombardments flattened Messina, where the German defensive was entrenched. Other cities were not spared. In fact, parts of Palermo are still strewn with rubble from World War II bombings, largely because government funds for rebuilding were misappropriated by corrupt officials who were linked with the Mafia.

In the early 1980s, a Mafia war left Palermo’s streets strewn with blood and the Corleone-based clan the undisputed victors. In 1992 two anti-Mafia magistrates were murdered. The terror continued with bombs in Milan and Rome that killed bystanders. The revulsion sparked in Sicilians by these assassinations has since weakened the Mafia’s grip on public opinion and dented the age-old code of loyalty (omertà). A grassroots association (Addiopizzo) was set up to fight against the payment of the pizzo, protection money, and since it was founded hundreds of businesses across Sicily have signed up.

No one could pretend however that Costa Nostra has disappeared. Its influence is still shaping politics and it is more often than not seen as the cause of Sicily’s economic stagnation. In 2016 the island had a debt pile of €8 billion, which is endangering Italy’s already frail financial state. Sicily’s economy is based on public sector wages: there are around 150,000 public sector employees among a population of over 5 million, mostly underused and employed on the traditional jobs-for-votes exchange. Unemployment is at 22 percent, twice the national average. Also, Sicily, and its tiny island of Lampedusa in particular, has been struggling for several years with the influx of migrants from Africa. Since 2014, over 500,000 migrants have landed in Italian ports and the surge shows no sign of abating. On the positive side, tourism is on the up, with an increasing number of visitors to the island, attracted by vastly improved accommodation, rural and island retreats, restored sites and rejuvenated historic centres.