'To see only the ball is to see nothing at all.'

Nelson Rodrigues

The proprietor picks up the phone and introduces himself.

'Mauro Shampoo,' he says, firmly. 'Football player, hairdresser and man. I'm the only one in Brazil.'

He adds: 'Would you like to make an appointment?'

Mauro Shampoo is dressed in his football kit. He finishes the call, puts the phone and scissors to one side and starts to kick a ball in the air. He wants to show me that even though he has hung up his boots he has not lost his touch. He manages to juggle the ball in the tiny space between his customers without it falling down.

In his permed prime Mauro Shampoo was captain of Ibis, a club in the first division of the Pernambuco state championship. In the late 1970s, Ibis went for three years without winning a game. The team became known as the Worst in the World. 'It was a great privilege to have that reputation,' he says. 'We even had a fan club in Portugal. When we started to win they sent us angry telegrams.'

While he was a footballer Mauro kept his day job as a hairdresser, hence the nickname Shampoo. It also inspired him to call his wife Pente Fino, or Toothcomb, and his children Cream Rinse, Secador and Shampoozinho, or Dryer and Little Shampoo. Retired from the game, he runs his own salon in Recife. He is a cult figure among local footballers, who regularly drop in for a cut and dry.

Silly nicknames are not exclusive to Brazil's worst players. Dozens of the best have been known by preposterous noms-de-plume. The habit started early. In the national team's first match, in 1914, there was a forward called Formiga, or Ant. Brazil's attack in the 1930 World Cup was led by Preguinho, or Little Nail. The following decades saw the new faces Bigode, Nariz and Boquinha (Moustache, Nose and Little Mouth) all play for their country. Most inappropriately, the tough-looking captain of Brazil's 1994 World Cup-winning squad was called Dunga. It is the name of Dopey in translations of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

Brazilians are obsessive nicknamers. It reflects their informal, oral culture. There is a town where so many people have nicknames that the phone directory lists them that way. Cláudio, in Minas Gerais, has 22,000 inhabitants. 'We rarely know people by their real names here,' explains the book's editor. 'If we didn't have a nickname directory, people would hardly use the phone.'

Nicknames may be used by the members of any profession, no matter how high-level. The ex-governor of Piaui state is formally called Mao Santa, Holy Hand, and the president of the Rio Football Federation is Caixa D'Agua, Water Tank. Luis Inacio da Silva, the left-wing presidential candidate in the last three general elections, changed his name by deed poll to include his nickname 'Lula' so as to make it clear on ballot papers who he was.

I raised my eyebrows one lunchtime in April 2001, when the TV sports bulletin announced that Caniggia and Maradona had both scored goals in domestic games. I had thought that Caniggia was playing in Scotland and Maradona had retired years ago. Yet Caniggia had put one away for Rio Branco in the Paraná state championship and Maradona for Ferroviaria in Ceara. Both players are Brazilian duplicates, named after the Argentinians for physical similarities; Caniggia because he used to have long hair and Maradona because he is stocky and short.

Footballers are often nicknamed after other footballers. It makes sense. A boy with outstanding sporting skills is more likely to be called Zico than, say, Zarathustra. In 1990, Argentina knocked Brazil out of the World Cup. (It was a Caniggia goal from a Maradona pass.) The defeated team included Luis Antonio Correa da Costa, whose professional name is Müller. He was named after the German striker Gerd Müller. Gerd went to two World Cups, in 1970 and 1974. Not bad, but his namesake went one better – he went in 1986, 1990 and 1994.

The age gap between the Müllers meant that they never faced each other. In Brazil footballers have played against the people who inspired their names. Roma was so called because he reminded friends of Romario, who is thirteen years his senior. In late 2000, they eventually played in the same match, Roma for Flamengo and Romario for Vasco. Newspapers commented that the younger one played more like Romario than the veteran did.

Sometimes names describe the way the footballer plays, such as Manteiga, Butter, whose passes were slick. Pe-de-Valsa, Waltzing-Foot, danced for Fluminense and Nasa, who played for Vasco, heads the ball like a rocket. Nicknames also paint a social portrait. In 1919, when the Brazilian national team was made up uniquely of whites and mulattos, they played a Uruguayan team that included a black player, Gradin. He was the first black international to play in Rio. Soon afterwards many black Brazilians were given the nickname Gradim (the 'm' is the Portuguese transliteration). By 1932 a Gradim appeared in the Brazilian national side.

Coming from a European culture very sensitive about racism, I was very struck when I first arrived in Brazil about how common and acceptable it is to refer to someone by their skin-colour. Many footballers' names, were they British, would mobilise the Commission for Racial Equality. There was once a famous player called Escurinho, or Darky. Telefone was so called since telephones used always to be black. Neither Petroleo, Petrol, nor Meia Noite, Midnight, left any doubt as to their complexions.

Pretinha, which means Little Black Girl, played for the women's national team during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Her name manages to offend European sensibilities not only of race but also of gender. And what to make of her teammate Marileia dos Santos? Ms dos Santos registered herself in the competition under the name Michael Jackson. She was named after the pop star because of a musical gait. When she was put on as a substitute in the third-place playoff, she did not moonwalk on to the pitch. Even so, when her name was announced, the crowd erupted in laughter.

Referring to someone by their nationality – or by the nationality that their physical features suggests – is not offensive. You could draw a map of Brazilian immigration just by tracing the names of footballers' international nicknames. Polaca, Mexicano, Paraguaio, Tcheco, Japinha, Chinesinho, Alemao, Somalia and Congo (Polack, Mexican, Paraguayan, Czech, Little Japanese, Little Chinese, German, Somalia and Congo) were all players. Near the Uruguayan border many are called Castelhano, Castilian, just because they speak Spanish.

As well as providing a lesson in world geography, names also sketch a map of Brazil. Many players gain the nickname of the town or state they are from. Brazil is a huge country and internal migration is great. Often a player's home town is the most obvious thing that distinguishes him from his colleagues. In recent years the accepted way of differentiating two players with the same name is to add the home state. When Juninho was transferred back to Brazil after playing at Middlesbrough he became known as Juninho Paulista – Juninho from São Paulo-because his team contained another Juninho, who became Juninho Pernambucano – Juninho from Pernambuco. The more informal moniker is always preferred, rather than – heaven forbid! – using the Juninhos' surnames.

Brazilians are a very body-conscious people. To call someone vaidoso, or vain, is often a compliment, since they are fulfilling their social obligation to be beautiful. Unfortunately for Airton Beleza, Airton Goodlooking, he won his title for being the opposite. Marciano, Martian, was not named ironically. Neither was Medonho, Frightful. Tony Adams is lucky he is not Brazilian. Otherwise there could have been two footballers called Cara de Jegue, Donkey Face.

Footballers have been nicknamed almost everything. Even numbers. There was a player called 84, one called 109 and another called Duzentos, Two Hundred. Animals are well catered for – Piolho, Lice, Abelha, Bee, and Jacare, Alligator. (Jacare is less remarkable for his name – the result of a hereditary protuberant chin – than for his status as tennis player Gustavo Kuerten's favourite footballer. When Kuerten won the 1997 French Open he praised Jacare in interviews. On the back of the recommendation, the footballer was sold from the small club in Kuerten's home town to a big club. He ended up in Portugal, although he returned shortly afterwards. Kuerten is a tennis player, not a talent scout.)

Nicknames increase the theatrical aspect of Brazilian football. They contribute to its romance. Pelé would have played the same had he been known by his real name, Edson Arantes. Yet the word 'Pelé' contains some of his magic. Its simplicity and childishness reflects the purity of his genius. How could Pelé be real if he did not have a real name? Pelé is less a nickname than it is a badge of his greatness, the name of the myth, not of the man.

'Pelé' has no other meaning in Portuguese, which increases the sense that it is an invented international brand name, like Kodak or Compaq. The etymological origin of 'Pelé' is much discussed but still unclear. Edson was known as Dico at home. When he joined Santos he was called Gasolina, Gasoline. Then he became 'Pelé'. Nicknames, like wines, can improve through time.

The use of nicknames also conveys the idea of extended childhood – of men who have not grown up. Some Brazilians believe this is internalised, creating a low sense of self-esteem.

The writer Luis Fernando Verissimo goes further. He believes that nicknames are a historical relic from the times of slavery. 'The footballer's nickname was less a "stage name" than a name from the slave quarters, a way for him to know his place and his limits,' he writes. Instead of showing equality and inclusiveness, he argues, nicknames reinforce a culture of submission.

Imagine you were faced with a team consisisting of Picole, Ventilador, Solteiro, Fumanchu, Ferrugem, Gordo, Astronauta, Portuario, Gago, Geada and Santo Cristo {Lollipop, Ventilator Fan, Single Man, Fu Manchu, Rust, Fatso, Astronaut, Docker, Stutterer, Frost and Holy Christ)-all of which are or were names of professional players. You probably wouldn't take them seriously. Exactly, thought the radio commentator Edson Leite.

After the 1962 World Cup many players were near retirement. Brazil overhauled its squad. The new team started to lose. Whose fault was it? Edson Leite blamed the nicknames. They were at best childish and at worst embarrassing. Of course a team that sounded like it had been found in a kindergarten playground would be awed in the presence of, for example, Argentina, which had grand, almost pompous-sounding players called Marzolini, Rattin and Onega.

For a brief while Edson Leite ran a campaign to call Pelé, Edson Arantes, and Garrincha, Manuel Francisco. It gained a fair momentum, but eventually failed. There was one major flaw. Nicknames may be puerile but they are often a lot less silly-sounding than players' real names.

Luiz Gustavo Vieira de Castro runs the register at the Brazilian Football Confederation. When I meet him a pile of paper is stacked high on his desk. The forms are applications to inscribe new players. He picks up one arbitrarily and reads it aloud.

'Belziran José de Sousa.

'Bel. Zi. Ran' he repeats, dwelling on each syllable.

'Elerubes Dias da Silva.'

'Ele. Rubes,' he sighs.

'Look – just one of the first seven names is normal.'

'Belziran?' he asks, as if it was a particularly rare species of Amazonian beetle. 'Elerubes?' Luiz Gustavo's mouth curls and he shakes his head.

'Whatever happened to José?' he implores. 'Now there's a good name.'

Luiz Gustavo says that Brazilians' names are increasingly ornate. It saddens him. He feels it is an indication of a lack of education. Made-up names are an embarrassment – not just for the poor soul involved but for the country too. He shows me a list of about 200 professional footballers that prove his point. The roll call goes from Aderoilton and Amisterdan to Wandermilson and Wellijonh.

Whether or not Brazil's culture of naming is the result of ignorance, it is certainly an extension of the creativity applied in other fields. If Brazil changed football it did so only by breaking orthodoxies and rewriting the rules with a playful, elastic flamboyance. The same process produced Tospericagerja.

In 1970 the aforementioned baby was born. He incorporates the first syllable of more than half the team that won that year's World Cup: Tostao, Pelé, Rivelino, Carlos Alberto, Gerson and Jairzinho. Another 1970 child was Jules Rimet de Souza Cruz Soares, named after the World Cup trophy. Jules Rimet proved worthy of the tribute – he became a professional footballer, in the Amazonian state Roraima.

World Cups have left a trail of onomastic devastation. In celebration of victory in 1962, a child was named Gol (Goal) Santana Silva. Perhaps Gooooool Santana Silva would have been more accurate. Whenever his mother screamed at him, passers-by must have thought: 'Who scored?' During the 1998 World Cup semi-final penalty shoot-out with Holland, a baby was named Taffarel each time he made a save. Regardless of the tot's sex. First, Bruna Taffarel de Carvalho was born in Brasilia. A few minutes later, when the keeper's defence won the match, Igor Taffarel Marques was born in Belo Horizonte.

Zicomengo and Flamozer sound like two Texan cops from a low-budget TV show. They are, no less glamorously, two brothers who incorporate 'Flamengo' with two of its stars from the 1980s, Zico and Mozer. It was the idea of Fransisco Nego dos Santos, a night watchman who lives more than 1,000 miles from Rio. Even his daughter, Flamena, could not escape his passion. When Fransisco took his children to meet Zico, he was deeply disillusioned. He said bitterly afterwards: 'Zico treated me like I was a mental retard.'

A conventional Brazilian way to name a child is by creating a hybrid word from the mother and father's name – as if the name is a metaphor for the physical union. Gilmar, for example, is the joining of Gilberto and Maria. Gilmar dos Santos Neves was born in 1930. Gilmar grew up to become Brazil's most successful goalkeeper, winning the 1958 and 1962 World Cups.

Gilmar Luiz Rinaldi, born in 1959, was one of several children named in his honour. As may be expected, the young Gilmar was a hostage to his namesake. 'Whenever I played football I was always put in goal,' he says. 'No one let me play in any other position.' But Gilmar discovered he had a talent. He eventually turned professional and was called up for the national side. In 1994 he won a World Cup-winners medal as Taffarel's reserve. Name had determined nature. Gilmar had become his namesake.

First names are especially relevant in Brazilian football since, together with nicknames, that is how footballers are generally known. Brazil and Portugal, its former colonial power, are the only countries in which this is the case – and Portugal much less so, since it is a more traditional, ceremonious society. First-name footballers are a reflection of the informality of Brazilian life. 'The Brazilian contribution to civilisation is cordiality – we gave the world the cordial man,' wrote the historian Sérgio Buarque de Holanda. You can call someone by their first name or nickname even in the most official situations. Politicians, doctors, lawyers and teachers are addressed the same way as you address a close friend. In a Brazilian record shop George Benson, George Harrison and George Michael are listed together, under G. (Brazilians are also tireless in using the suffixes '-inho' and '-ao' – meaning 'little' and 'big' – which increases the impression that the country is both excessively intimate and exaggerative. In the 1990s many Ronaldos played for the national side. The first three were easy to name: Ronaldao, Ronaldinho and Ronaldo, Big, Little and Regular-sized Ronaldo. Easy. But in 1999 another Ronaldinho turned up. What was left? Would he be nicknamed Ronaldinhozinho, Even Littler Ronaldo} No. He was first called Ronaldinho Gaucho, Little Ronaldo from Rio Grande do Sul. Then, since he was no longer so little, the original Ronaldinho graduated to Ronaldo (the first Ronaldo was no longer in the squad) and so Ronaldinho Gaucho became Ronaldinho.)

Using first names was one of the first ways, in the early years of the last century, that Brazilians changed football's conventions. They at first imitated the English expats, whose teams were listed by surname. But it did not stick. How could you distinguish two brothers? The confusion was resolved the Brazilian way. When teams were mixed with Europeans and Brazilians, naming style determined nationality. Sidney Pullen was known as Sidney because he was a Brazilian, albeit of English descent. His team-mate Harry Welfare, born in Liverpool, was always Welfare.

Brazilian football is an international advert for the cordiality of Brazilian life because of its players' names. Calling someone by their first name is a demonstration of intimacy – calling someone by their nickname more so. Brazil feels like a team of close friends; mates from the kickabout at the park. It fosters an affection that no other national team commands. The fan personalises his relationship with Ronaldo by virtue of using his first name, which does not happen when you call someone Beckenbauer, Cruyff, or Keegan.

Because footballers are known by first names and because Brazilians are imaginative namers, players are a great window on national concerns. One of the most common names for footballers is Donizete. In 2000 there were three Donizetes in the Brazilian first division. It is not a traditional name. Fifty years ago there were no Donizetes. Two centuries ago, however, there was an Italian opera composer called Donizetti. A Brazilian music-lover named his sons Chopin, Mozart, Bellini, Verdi and Donizetti. The latter became a priest who, in the 1950s in São Paulo, became a famous miracle-worker. It spawned a wave of Donizetes. One estimate puts the number at more than a million people.

American culture is a strong inspiration for babies' names, especially Hollywood. Not just film stars but the place itself. Oleiide was a strong club player in the 1990s. He tended, however, to be known by his nickname, Capitao, or Captain. Since he was often captain, this was very convenient. How long before Brazilian football does away with proper names all together?

Alain Delon, the French actor, once said: 'It's much more exciting being a football player than being a film star. To be honest, that's really what I wanted to do.' He must be tickled by the success, if not at the spelling, of his South American namesake. For a period in 2001 Allann Delon was highest scorer in the Brazilian league. 'I might not have the actor's eyes, but I'm charismatic and always a success with the ladies,' jokes the twenty-one-year-old, a squat mulatto with thick eyebrows and matty black hair. He was very nearly called Christopher Reeves, but his mother changed her mind – swapping one misspelt film idol for another. 'Can you imagine how weird it would sound "Christopher Reeves shoots into the corner of the net",' he says. 'Allann Delon is much better.'

The cast list of Brazilian Football: The Movie also includes Maicon, who has played for Brazil's youth side. His father paid tribute to Kirk Douglas by naming his son Maicon Douglas, after Kirk's son Michael. The man at the register office wrote it down wrong.

Other celebrities in football boots include Roberto Carlos, the veteran left back, who was so called because his mother liked the real Roberto Carlos, who is Brazil's equivalent of Frank Sinatra. The tribute turned out to be especially poignant, since the singer was run over by a train in his youth. In other words: the footballer with one of the most coveted kicks in the game was named after a man with a gammy leg.

Roberto Carlos's music is subtly contained in another footballer: Odvan, who played for the national team in 1998. His mother was so taken by the song O Diva, The Divan, that she immortalised it on his birth certificate.

Spelling mistakes due to transliterations are often the result of ignorance, but not always. Brazilians have a relaxed attitude to spelling. It is often used as a device to customise names, rather than as a convention to be obeyed. Less-educated parents tend to prefer the aesthetics of the letters 'w', 'k' and 'y', which are not part of the Portuguese alphabet, and also lovingly run two consonants together. Allann Delon's father could not remember how the Frenchman spelt his name so he added an T and an 'n' for good measure. Registrars are obliged to take down the name that the parent dictates. In 2000, a magazine reported that 'Stephanie' was so popular that a registrar in São Paulo listed seventeen different spellings (from Stefani to Sthephanny) and asked parents to choose by number.

Inconsistent spelling was not one of the major grounds for Congress's football investigations. It could have been. And for a moment it seemed that it was. At the beginning of ex-national coach Wanderley Luxemburgo's testimony, Senator Geraldo Althoff asked him: 'How will you sign your name?'

The senator looked like an exasperated headmaster berating a naughty pupil. He said: 'Will you use a W and a Y or a V and an I?'

It was a simple question, in spite of the accusatorial tone and the humiliating circumstances of the interrogation, but Luxemburgo could not give a straight answer.

He replied that his signature would be Wanderley and his documents would read Vanderlei. Althoff had the rankled expression of a man at the end of his tether. How could he believe a word the man said if he was in two minds as to his own identity?

Questionable spelling, it seems, comes with the job of national coach. Luxemburgo's predecessor, Mário Zagallo, misspelt his name for almost fifty years.

Zagallo was born Zagallo on 9 August 1931. He became the footballer Zagalo during the 1940s. Zagalo played for Flamengo, Botafogo and the national side. Zagalo won four World Cup-winners medals. Always Zagalo. Never Zagallo.

Then one day, around 1995, the veteran was giving a talk at a São Paulo newspaper. A reporter enquired about his surname. He replied that on his birth certificate it had a double T. The following day the newspaper printed Zagallo.

Gradually other newspapers and TV stations followed suit. Books rewrote his achievements with his 'correct' name. The desire for spelling rigour turned into a self-contradictory mess. For a while Zagallo kept on signing a newspaper column Zagalo, even though the same newspaper in other articles spelt him differently. Zagalo might have been a mistake, yet it was nevertheless his footballing identity. It was doomed to be erased from history.

The episode is less a victory of thoroughness over inaccuracy – or of punctiliousness over common sense – than a demonstration that Brazil is a strongly oral culture. What does it matter to Luxemburgo if he is Wanderley or Vanderlei, or to Zagallo if he is has one '1' or two? Both names sound the same.

Zagallo's name stands out in another way. He is the only Brazilian forward who has won a World Cup final to be known by his surname. So what? This explains a great deal. The coup de grace of Brazilian naming customs is that you can often identify the position of a footballer depending on how he is known. Goalkeepers tend to be known by their surnames and first names; forwards by their nicknames. Zagallo is the exception that proves the rule.

I compiled a quick list of the Brazilian national team's all-time top scorers. Seven of the first ten are known by their nicknames. In fact, the only surname among the top twenty-five is Rivelino – but this should not really count. First, it sounds like a nickname. Secondly, Rivelino really is a nickname – his real name is Rivellino. Part of the artifice of a Brazilian goalscorer is to have a name that bluffs.

Zagallo was not a flashy left-winger. He did not deserve a nickname. He did what was expected, nothing more.

Likewise, Brazilian goalkeepers rarely have nicknames. Of the nine goalkeepers to have had more than twenty national caps, four are known by their surname and four by their first name. Only one is known by his nickname – Dida-and that took eighty years to come about. He won his first cap in 1995.

Defenders also tend not to have nicknames, although the phenomenon is less extreme than for goalkeepers. 'There is always the impression that a defender who uses a nickname does not take responsibility for his actions. Who can trust a defence that has a pseudonym?' asks Luis Fernando Verissimo. 'The ideal defensive line-up should list the defenders with their surname, their parents' name, national insurance number and a telephone number for complaints.'

If referring to someone by their nickname shows intimacy and affection, then Brazilians are fonder of their attackers than of their defenders. Which we know already. And as for goalkeepers? Their surnames reinforce the fact that they are loved less. No wonder they are tormented souls. According to a popular saying: 'The goalkeeper is such a miserable wretch that the grass doesn't even grow where he stands on the pitch.'

The list of unhappy owners of the number one shirt predates Barbosa, who suffered for fifty years after letting in one goal. Jaguare was Brazil's best keeper in the 1920s and 1930s. He would catch the ball with one hand and then spin it on his index finger. He would dribble opponents or bounce the ball on their heads when their backs were turned. Jaguare went to Europe, where he played for Barcelona and Olympique de Marseille. But he spent all his money as soon as he earned it. One year after returning to Brazil, in 1940, he was found dead in a gutter. Castilho, who played for Fluminense between 1947 and 1964, committed suicide. Pompeia and Veludo – two other flamboyant Rio goalkeepers from the 1950s, ended up alcoholics.

Brazilian goalkeepers have to find love from other quarters. Pompeia said: 'The goalkeeper likes the ball the most. Everyone else kicks it. Only the keeper hugs it.' This affection was reciprocated in a delightful children's book written by Jorge Amado, Brazil's most famous novelist. It tells the story of a ball who falls in love with a talentless goalkeeper. The keeper becomes unbeatable since the ball always heads for his arms, where it is kissed and then warmly held to his chest. One day, the goalkeeper has to defend a penalty which he does not want to save. So he runs away, leaving the goal wide open. But the ball chooses to follow him. They marry and live happily ever after.

It is not only in Brazilian literature that the ball is considered a real person. Players of a certain generation – when football was less about force and more about delicacy-describe the ball as a lady to be courted. 'The ball never hit me in the shin, never betrayed me,' says Nilton Santos, who played for the national side between 1949 and 1962. 'If she was my lover, she was the lover I liked the best.' Didi, Nilton Santos's team-mate in the 1958 and 1962 World Cups, opined: 'I always treated her with care. Because if you don't, she doesn't obey you. I would dominate her and she would obey me. Sometimes she came and I said: "Hey! My little girl," . . . I treated her with as much care as I treated my wife. I had tremendous affection for her. Because she's tough. If you treat her badly she will break your leg!'

One of the reasons why Brazilians regard a ball as a woman is semantic. In Portuguese, 'a bola' – the ball – is a feminine noun. (Unlike 'el balon' in Spanish or 'le ballon' in French, which are masculine.) Since Portuguese has no word for 'it', the ball is always described as 'her' or 'she'. In a verbal culture in which there is a tendency to give everything nicknames, it was only a small step until the ball grew human characteristics.

If a player is scared of touching the ball, commentators say he is 'calling the ball "Your Excellency"'. If he is displaying

intimacy with the ball, he is 'calling the ball "my darling"'. I cannot imagine that eskimos have as many words for 'snow'

as Brazilians do for 'bola', ball. Haroldo Maranhao, in his Football Dictionary, lists thirty-seven synonyms:

Leather balloon, child, girl, doll, chubby one, Maricota, Leonor, pellet, Maria, round one, mate, sphere, kernel-stone, balloon,

her, infidel, plum, leather, little round one, baby, pursued one, globe, wart, chestnut, leather sphere, young lady, Guiomar,

Margarida, mortadela, little animal, capricious one, deceitful one, demon, tyre, bladder, number five, leather ball.

Five are women's names. Margarida is Margaret. It gives a whole new meaning to the phrase: 'Pass the Marge.'

'In Brazil you can call the ball anything,' jokes the radio commentator Washington Rodrigues. 'Except "ball".'

Once before a match between two small Rio teams, Washington took the personification to another extreme. He declined to interview

the players. Instead, he interviewed the Margaret. How did she feel to play among two small teams when she had once played

with Pelé? Didn't she feel like giving up, throwing in the towel? The interview lasted ten minutes and ended with the ball

in tears.

Radio bears a lot of the responsibility for the richness of Brazilian football talk. Radio influenced football more than any other medium. It was the vehicle that turned football into a mass sport by allowing all corners of the country to follow games. Radio was more suited to Brazil than newspapers since the country is so big and large parts of the population were illiterate. Radio grew in parallel with football-the 1950s and 1960s were both the golden age of Brazilian football and the peak of popularity of transmissions.

Radio gave football a language of its own. Right from the earliest sports broadcasts the aim was to create as much excitement as possible rather than clinically describe what was going on. In 1942 Rebelo Junior, a commentator who started his career narrating horse-races, invented sport's most famous prolongated vowel. A player scored and he shouted 'gooooooaP.

Rebelo Junior was nicknamed the Man of the Unconfoundable Goal. His unconfoundable 'gooooooaP echoed through history and is now a mark of all Brazilian – and Latin American – radio and television football coverage. His colleagues found that it had advantages. Raul Longas, nicknamed the Man of the Electrifying Goal, wailed like a siren for longer than his peers. There was a reason. He was short-sighted and could not properly see who scored. The extra seconds allowed his sidekick to write down for him the player's name on a piece of paper.

The most listened-to football commentator during the 1940s and 1950s was also the most idiosyncratic and colourful. He is, still, one of the most listened-to Brazilians in the world. Ary Barroso wrote many of Carmen Miranda's most famous songs. He also wrote the light samba 'Aquarela do BrasiP, translated as 'Brazil', which is one of the most performed pieces of music of all time. It has been recorded by as diverse artists as Frank Sinatra, Wire, Kate Bush and S'Express.

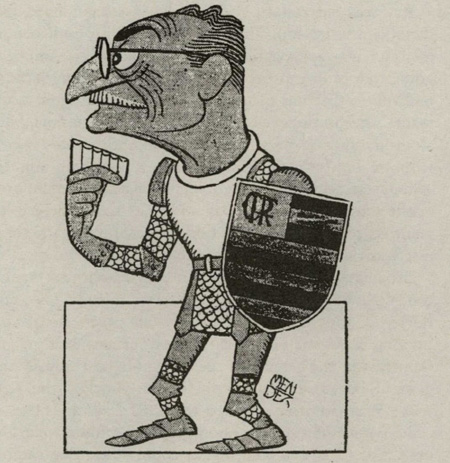

Ary was a Renaissance man. As well as writing music he was a football commentator, pianist, writer, local councillor and, later, a television-show host. Ary was also a Flamengo fan. It would not be unfair to say that he was a Flamengo fan above all his other roles. In the early 1940s his compositions had made him internationally famous. He flew to Hollywood and was invited to become musical director of Walt Disney Productions. For a composer, there was possibly no higher position in showbusiness. He refused.

Ary Barroso

'Because don't have Flamengo here,' he explained, ungrammatically.

Ary's love for Flamengo eclipsed any impartiality he might have had as a commentator. Instead of shouting 'goooooal' Ary blew into a plastic mouth organ. It was easy to tell who had scored. If it was Flamengo the mouth organ would squeal repeatedly with joy. He would blow extended flourishes like an excited child. If it was against Flamengo the organ would emit a short, embarrassed 'frrp'.

Ary was entertaining because he was passionate, unpredictable and irresponsible. He once told his audience when a striker was approaching the Flamengo box: 'I'm not even going to look.' Another time the radio fell silent because he had run to the edge of the pitch to celebrate a goal with the team. Yet, his audience was not just Flamengo fans. He was a parody of the general Brazilian assumption that everything is motivated by personal interest. In the closing minutes of a match in which Flamengo was losing 6-0, a man arrived at the stadium willing to pay any price to be let in. 'I don't want to see the game,' he told the confused gatekeeper. 'I just want to see Ary Barroso's face.'

Brazilian football authorities allow journalists on the touchline during the match, interviewing players and the referee as they come on and off. This practice was started by Ary Barroso. He was the first broadcaster to put a reporter on the pitch – to get him different angles on the game. This created situations which shocked the English when Southampton travelled to Brazil in 1948. 'The usual radio commentators and photographers refused to be kicked off the field so that the match could start. The radio and press seem to be the deciding factors in this country about the time when a match shall commence!' tut-tutted referee George Reader in a dispatch to the Southern Daily Echo.

The importance of radio within football has led to another peculiarly Brazilian phenomenon – the 'radialista'. The radi-alista is ostensibly a radio broadcaster, yet because the idea is to be as showy as possible they are celebrities in their own right. Many radialistas take advantage of football's prominence to launch themselves in other spheres. Reporting on football matches teaches you skills such as public speaking, thinking on the spot and how to rouse a crowd. The list of politicians, businessmen and lawyers who started their careers commentating on local football matches is a long one. Rio state governor Anthony Garotinho aims to be the first ex-radialista to become Brazilian president.

Radialistas can be anything they want to be. Washington Rodrigues, the interviewer who reduced a football to tears, jumped to the other side and became coach of Brazil's largest club. It was the equivalent of making Des Lynam coach of Manchester United.

Washington does not look like a sportsman. When I meet him at his radio studio his ample physique is comfortably rested in a chair. He is genial and soft-spoken. Washington's broadcasting style is not the firework variety; he is the most verbally creative of his peers. He has coined more than eighty phrases, of which several have passed into common usage. His style is witty and intimate, for example calling fans in the geral standing area Geraldines and those in the arquiban-cada terraces Archibalds.

Washington – like Ary Barroso – is a dyed-in-the-wool Flamengo supporter. He has never hidden it. It is a trademark of his style. When, in 1995, Flamengo were in trouble the club's president – himself an ex-radialista – wondered who could pull them out of the crisis. He asked Washington, even though he had never been a coach, a player or even a linesman before.

'What were Flamengo looking for?' Washington says. 'The club wanted internal peace. They wanted someone who could identify with the fans. I am not a coach, nor do I have pretensions of being one. But everyone knows what football is. We are all football coaches really.'

The radialista was given a four-month contract as coach. 'What did I do?', he asks. 'Tactics is like a buffet. If there are forty plates you eat four or five. You don't eat all forty. I asked all the players to put on the table their ideas about the best way to play. Then I put mine and afterwards we chose the best.'

Washington introduced other unorthodox methods. He was unable to understand games standing on the touchline because he had only ever seen football from his position in the radio cabin. So he asked the Brazilian Football Confederation if he could install a television in the dugout. They were unsure and asked FIFA. FIFA replied that it was unsure, since it had never been asked before. Eventually, it gave him the all-clear. Washington sat in the dugout, watching television instead of watching the players.

He lasted his four-month contract. He did not turn Flamengo into champions, yet he had moderate success. The club must have been happy enough since three years later, when the club was again in difficulties, he was given another four-month contract. In his second stint he helped Flamengo avoid relegation from the first division of the national league.

He adds: 'It was an educative experience. In forty years I didn't learn as much as I learnt in those eight months. I started to see players in a different light, how they are during the week, what their personal lives are like. It made me regret a lot of things I had said or written before. I am really careful now in criticising a coach.'

Football journalism has been the start of many eminent Brazilians' careers. On 5 March 1961, Joelmir Beting was at the Maracanã, reporting on a game between Santos and Fluminense. He saw Pelé take the ball just past the centre line and dribble one, two, three, four, five . . . six players before beating the goalkeeper. It was a work of art. Those present say it was the most wonderful goal he ever scored. But it was before the era of televised games. The dribble would never be seen again.

Joelmir thought that a way to make the goal eternal was to cast it in bronze. He commissioned a plaque that was put up in the stadium the following week, dedicated to 'the most beautiful goal in the history of the Maracanã'. The phrase 'gol de placa' – goal worthy of a plaque-entered the lingua franca, and is still the highest compliment in Brazilian football.

Joelmir now has a different plaque. He is a distinguished financial commentator.

Football was also a trampoline for Brazil's Monty-Pythonesque comedy troupe Casseta & Planeta. The humorists started a satirical magazine in the 1970s. Later they were given their own show by Globo, the main TV station. In 1994, Globo asked them to provide daily sketches during the World Cup. During the tournament they broadcast clips from the United States for the lunchtime and evening news bulletins. 'None of the international journalists really knew what was going on,' says Bussunda, one of Casseta &c Planeta's comedians. 'Here was a bunch of Brazilians dressed up in ridiculous costumes making complete fools of ourselves wherever the national team went.'

When Brazil won the final – in Los Angeles' Rose Bowl – they filmed a spoof video dressed as Californian hippies singing 'The Age of Romarius', to the tune of the 1960s anthem 'Aquarius'. It was one of their best-received gags. By the end of the World Cup Casseta & Planeta had a celebrity status almost as big as the footballers themselves.

'When we flew back to Brazil it felt like we were champions too,' says Bussunda, whom I meet sitting in his office in Ipanema.

Casseta & Planeta now have a weekly primetime show on Globo. They carry on writing gags based around football. 'Football is a very rich seam. If we were writing just about what goes on on the pitch, then maybe there wouldn't be enough material. But when you are talking about football you are talking about Brazil,' he says.

Bussunda is a TV natural. He makes you laugh just by looking at him. His expression is wonderfully glum and he is blessed with a portly comedy stomach. His obesity is part of his act. The catchline for his weekly articles in the sports newspaper Lance! is: 'the columnist who is a ball already'.

Casseta & Planeta is my favourite Brazilian television programme. The satire is no-holds-barred. They send up politicians, personalities and even Globo itself. Sometimes I can't believe what they get away with.

I ask Bussunda whether any of their victims have ever complained? He looks at me with a straight face. 'The only time we ever received external censorship was when we were planning a sketch about Fluminense.'

The incident occurred when Romario was playing for Flamengo, who are Fluminense's arch rivals. Casseta &Planeta invited him on the show and asked him to wear a T-shirt that said, 'Não use drogas. Não torça para o Fluminense'. Literally, this means, 'Don't take drugs. Don't support Fluminense'. But it is a pun on the word 'droga', which also means 'something rubbish'.

Fluminense went to court and obtained an injunction against the broadcast.

'So what did we do?' asks Bussunda. 'We played the interview with Romario right up to the moment he was going to show the T-shirt. Then we cut to images of three goals that had been scored against Fluminense the Sunday before.'

Bussunda did not realise the offence it would cause. His voice is deadly serious. 'I received several threats. I received emails saying that people knew where I lived, that they knew which school my daughter goes to. I was really taken aback. I even had to change telephone numbers.'

He adds: 'In my career it is the one joke I regret. I realised that the joke had hit the wrong target. We wanted to poke fun at the Fluminense directors. But we hurt the fans.'

Bussunda learnt that in Brazil there is only one thing you cannot joke about: a fan's passion for his club.

As well as Ary Barroso and Jorge Amado, football has been part of the public lives of many important cultural figures. Pixinguinha, a black musician who pioneered the use of Afro-Brazilian percussion instruments, wrote the first major composition dedicated to the sport. The song '1x0' was written in 1919 immediately after Brazil won the South American Cup by a goal to nil. The speed and dexterity of the music portrayed the skills of the goalscorer, Friedenreich. More recently, Chico Buarque, who is probably Brazil's most highly respected singer-songwriter, has written songs and articles about football. Chico also owns his own football pitch and amateur football club, where he plays three times a week.

In 1976 the contemporary artist Nelson Leirner was asked to design a trophy for Corinthians. A veteran of artistic 'happenings' during the 1960s, he decided to make a trophy that was a 'performance' rather than an object to keep. He made a Corinthians flag which was 4m by 8m and tied it to helium-filled balloons. The trophy was presented to the club during a match at the Morumbi in São Paulo – it was set free at the beginning of the game and drifted up and away out of the stadium.

Corinthians lost the game and Leirner was accused of causing the team bad luck.

A week later, the flag landed on a farm four hundred miles away. It was taken and put up in a bar in the nearest town. From that moment on the local team lost match after match. Its supporters blamed the flag. Corinthians had gone twenty-two years without winning a title. Perhaps the flag had brought the curse? They began to perform religious rituals to exorcise the bad spirits. Eventually, a television station heard of the story and returned the flag to São Paulo.

Literature and football have been linked since football's early days. In 1930, Preguinho, the Little Nail, scored Brazil's first goal in a World Cup. His father, Coelho Neto, was a novelist and founder of the Brazilian Academy of Letters. Coelho Neto was a die-hard Fluminense supporter. He attended games wearing a white suit, straw hat and walking stick. His elegant attire was no guarantee of writerly reserve – in 1916, complaining against a penalty, Coelho Neto led one of Brazil's first pitch invasions.

Despite his love of football, Coelho Neto did not include it in his fiction. Football, though enjoyed by all levels of society, was for many years not deemed serious enough for art. In 1953 it was considered scandalous when it featured in a play. A Falecida, The Deceased Woman, tells the story of Tuninho, a widower who wastes his wife's burial money on football because he discovers that she had been unfaithful.

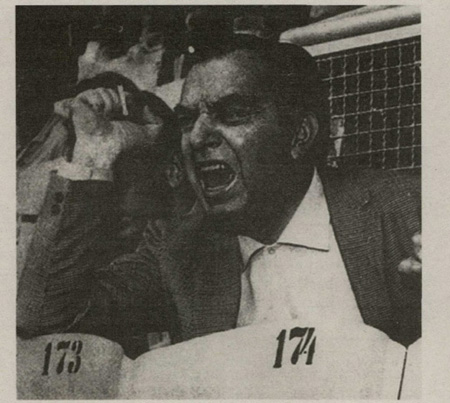

The Deceased Woman is by Nelson Rodrigues, Brazil's greatest playwright. Nelson adored causing offence. Usually the taboos he broke were more subversive than mentioning sport. He was obsessed with adultery and incest. Between 1951 and 1961 he published daily short stories in a Rio newspaper, almost always about marital infidelity. Nelson had a wonderful gift for dialogue and a wickedly perverse sense of humour. He described the hypocrisies of lower-middle-class Rio like no one before or since.

Nelson Rodrigues at the Maracanã

Nelson was the younger brother of Mário Filho, the pioneer of Brazilian sports journalism and the man who conceived the Maracanã. Of their ten other siblings that survived infancy, all went into journalism. When two of them started a sports magazine in 1955, Nelson was asked to lend a helping hand.

Nelson's columns took football-writing into a new dimension. For a start, he made up characters and situations. Perhaps he felt the freedom to do this was because he was not a sportswriter – he was a famous playwright. An equally likely reason was because he was so short-sighted that he could hardly make out the events on the pitch. For example, in order to explain flukish occurences, Nelson said it was the work of the Supernatural de Almeida, a man from the Middle Ages now living in a fetid room in a northern suburb of Rio. The Supernatural is an absurd concept, but his public loved it because it played into their own superstitions. It became part of football's vernacular. Several times I have heard commentators say, when trying to explain an unlucky bounce: 'Look! It's the Supernatural of Almeida!'

Nelson, without intending to, gave Brazilian football its clearest voice. It is a peculiar, if explainable twist of fate that Brazil's two most important football writers were brothers-since Nelson might never have started without Mário Filho's influence. Their styles were very different. Mário Filho's texts were serious opuses. Nelson, on the other hand, articulated the hyperbolic passion of a fan. 'I'm Fluminense, I always was Fluminense. I'd say I was Fluminense in my past lives.' He coined dozens of phrases that seem as relevant now as when he wrote them four decades ago. He described players like Pelé and Garrincha as transcendent icons – which no one had done before. Nelson was the first person to describe Pelé as royalty. 'Racially perfect, invisible mantles appear to hang from-his chest,' he said when the player was just seventeen. Pelé, of course, later became known as The King.

When games started to be televised, Nelson was not impressed. 'If the videotape shows it's a penalty then all the worse for the videotape. The videotape is stupid,' he said, famously. Nelson's Luddite comments are often quoted today. Partly this is because he reminds people of the golden years. But also it's because Nelson got it right. Brazilians do not like to be objective about their football. They like it to be halfway between fact and fiction. They like it to be as informal as possible; full of stories, mythologies and inexplicable passion. Football is about Ronaldo and Rivaldo but it is also about Margaret and Tospericagerja and Mauro Shampoo.