Branns & Parsons

Branns & ParsonsTowards the end, as Christmas approached, there had to be not just a card list but—

a present list

a food list

a drink list

a party list

a decoration list

and a guest list too.

All grew longer with the years. Finally, Louise opened an actual Christmas file, which would start in the first week of September, as soon as she had settled down after the summer holiday. By settling down she meant

— putting piles of post-holiday clothes through the washing machine.

— sorting, ironing, folding and finding places for the above.

— drying, shaking, brushing and storing the children’s tents and backpacks.

— finding space for touring bicycles somewhere other than the hall.

— collating, answering and paying accumulated letters and bills.

— telephoning, soothing, and generally re-establishing contact with relatives and friends.

— collecting, de-fleaing and worming pets.

— finding, collating and if necessary purchasing assorted school, college and sporting wear.

— putting in early orders, before the rush, for coal, wood, oil and getting the heating system serviced.

— getting the car serviced.

— getting the garden back under control.

The Christmas file, opened more-or-less as soon as all this was more-or-less done, would be closed in the second week of January, after the last straggling revellers had drifted back to work, and the last thank-you letters or I’m-sorry cards posted.

Then she would look at her hands: she would see broken nails and chapping skin and stand-out veins and know it was as much her fault as the season’s. Why didn’t she wear rubber gloves or remember to use handcream? Other women did. Perhaps it was her form of protest? But why did she want to protest? It was what she wanted to do, turkeys and tinsel and toys. She loved Christmas. Christmas was a kind of powerful bell, chiming once a year, deep and profound, to mask the passage of life. There was no point staring at her hands and lamenting the passing of the years. They passed anyway. She lived a busy and useful life. She loved her husband, and he loved her. The children were healthy and lively and attractive. She had nothing to complain about, except a kind of extraordinary proliferation, a domestic infiltration, which meant you couldn’t keep Christmas in the head any longer, but had to keep lists, and even lists of lists.

‘The difficulty is,’ Rupert (Louise’s husband) said to Louise, when they were both forty-five, ‘that we’re pinned between the generations. As the family below grows up, the family above grows down. One lot’s too young and the other lot too old to be responsible for themselves, so we have to do it.’

She made a list of the people he had to support. She made it on the paper napkin of the restaurant where they were having their twenty-second wedding anniversary dinner. It was 1979. The restaurant had offered linen napkins as late as 1977, before being finally forced, by the increasing costs of laundering, to go over to paper.

‘We shouldn’t mind,’ said Louise, comfortingly, ‘it means the laundry workers are getting a better deal.’ But Rupert minded. What was the point of struggle and success, if the traditional rewards melted before your eyes, disintegrated?

The list of the people Rupert supported, according to Louise, in 1979, went like this:

— Louise

— Adam (19)

— Simon (17)

— Polly (15)

— Zoë (12)

— Louise’s parents (contributions towards)

— Rupert’s parents (contributions towards)

— Rupert’s sister-in-law (contributions towards)

— Rupert’s nephew and niece (school fees)

— a workforce of 48 people

— secretarial staff of 3

— Louise’s cleaning lady

— the unemployed (contributions towards)

— non-ratepayers (contributions towards)

— the sick, the infirm, those too old, too young, or too disturbed in the head to work.

‘Not only are we pinned between the generations,’ said Rupert, ‘but we are squashed by ubiquitous taxes. We, the workers, the wealth-producers of this country, are just a thin, thin filling between thick slabs of non-productive bread. The thirty per cent of the population who work have to carry the burden of the seventy per cent who don’t. No wonder we’re tired.’ He never used to talk like that. Louise supposed it to be just the general drift towards the right that happened as men grew richer and older.

In 1979 Rupert’s firm – known as Rupert’s Own to the family – was in some slight difficulties, but nothing, no one imagined, that couldn’t be lived through. One day the recession would end. It just had to be lived through.

Rupert’s Own made dashboard instruments for specialist cars, for both home and export markets. The current difficulties were:

— contracting home markets

— new employment taxes

— inflation

— increasing union pressure

— the high cost and low quality of raw materials

— shortage of skilled labour

— a strong pound, limiting competitiveness abroad

and so forth. If the new light Californian wine they drank with their Osso Bucco – for everyone nowadays was diet conscious and meant to live for ever – tasted slightly sour, and he longed for good old-fashioned rich and gravelly claret, it was hardly surprising.

‘Well,’ said Louise, ‘never mind! I suppose we’ll be allowed to grow incompetent with the years in our turn, and then our children will have to look after us, as well as their children and then they’ll know what it was like for us.’

But would they? Nothing was what it had been. The children seemed uninterested in careers or earning money, but were content enough to just get by, and there was a distinct lack of grandchildren in their particular patch of the world. Without grandchildren how could there be grandparents? Self-help, it seemed, would have to go on till the grave, and beyond. You’d have to say prayers for yourself, for who else would there be to pray for you?

Louise and Rupert’s wedding anniversary was on December 3rd. In their early years together they’d saved the discussion of Christmas plans, such as they were, for that particular day.

— what do you want for Christmas?

— are we going to your parents or mine?

— if we bought Adam and Simon bunk beds would they accept that as a Christmas present, or would we have to supplement it with, say, a robot for Adam and a teddy bear for Simon, knowing they’re each sure to want what the other’s got?

— what shall we buy the in-laws?

The first Christmas had been the best – 1957. She and Rupert, students, he of engineering, she of mathematics – defying both sets of parents, neither going home, sharing the Christmas holidays in the days – well, the nights – before people did that kind of thing.

— a fir branch of a Christmas tree

— one silver star upon it

— a chicken and some packet stuffing

— a pound of potatoes for roasting

— some peas, some mushrooms (luxury) for frying

— a Woolworth’s Christmas pudding

— top of the milk to pour upon it

— some cigarettes, from her to him

— a new black bra, from him to her

— from both of them unto the other, the gift of themselves, the knowledge that this was the beginning, the great adventure

— a single bottle of wine.

Enough, enough! ‘No present,’ said her parents, the Parsons, ‘not this year, since you’re not coming home, but we understand and when you both actually get married we’ll put down the deposit on a house for you.’

General, but conditional, as always.

‘They really believe,’ Rupert and Louise sighed and smiled, unable in their happiness to take offence, ‘they really believe we’ll end up like them!’

Rupert’s parents gave him a dozen pairs of throw-away socks, and her a cookery book, which she still used, year after year, for the Christmas pudding. But at the time she puzzled and brooded. Presents have meanings – if the giver isn’t aware of it, the recipient usually is. She wrote alternatives down on the back of the one Christmas card she received that year – it was from a former boyfriend and she despised it.

Throw-away socks to Rupert – significance of

a) I can’t be trusted to wash his socks properly: i.e. domestically incompetent.

b) I’m not the kind to wash socks at all: i.e. a slut.

c) I’m eager to wash his socks: i.e. trying to trap him into marriage.

d) I shouldn’t waste my time washing his socks: i.e. too good for him.

Well, which did they mean?

‘For heaven’s sake,’ said Rupert, ‘they just gave me some throw-away socks.’

Recipe book for Louise – significance of

a) Can’t cook and should learn: i.e. has at least some kind of future with Rupert.

b) So boring that’s all she can do: i.e. has no future at all with Rupert.

The gifts seemed to be throwing up inconsistent signals. She didn’t understand them.

‘Look,’ said Rupert, ‘let’s not worry about this kind of thing. Stop making lists. It isn’t necessary.’

‘I have a kind of feeling it is,’ she said.

Within a few months she needed more than a suitcase under his bed for her clothes: she needed drawers and cupboards. She had a kind of vision of the way things were going to be. ‘Let’s just go to bed,’ he said. And so they did. Bounce, bounce, on top of the bulging suitcase. They went to the market and bought a proper chest-of-drawers, and by the following Christmas had a flat, not a room, and a cupboard under the stairs to stack the suitcases, and by the next Christmas were married and on the 1st of December the following year Louise gave birth to Adam. She had to spend Christmas Day in hospital because

a) the baby was slow to suckle

b) her stitches went septic

and Rupert went home to his parents, the elder Branns, and had far too much to drink. Now that would never have happened had it been her parents, the Parsons.

— one glass of sherry before dinner

— one bottle of wine with dinner, no matter how many guests

— and more than enough rum in the pudding for anyone, let alone brandy on top of it.

‘We’ll all be too tipsy to listen to the Queen’s speech,’ Mrs Parsons would say in alarm, as the wine cork was pulled, and because it was Christmas everyone tut-tutted in sympathetic alarm, instead of saying sadly, ‘I wish to God we were!’

For the following ten years the young Branns went alternatively to his parents on Christmas Day, and her parents on Christmas Day. Louise, Rupert, Adam, then Simon, then Polly, then Zoë. The senior Branns lived thirty miles away, the Parsons forty-five, fifteen miles, wonderfully enough, further down the same road. The car would be packed neatly and quickly on Christmas Eve, as would the children’s stockings. Into the car, as well as the everyday nappies, wipes, carry-cots and so forth went:

— 1 neat cardboard box, containing four prettily wrapped presents, two for the senior Branns, two for the Parsons.

They’d call in on the Branns for mid-morning sherry and mince pies and to drop off the presents, if they were Christmas lunching at the Parsons, and if lunching at the Branns, would drive on to the Parsons for Christmas high tea, and to drop off their presents. Simple.

When the children grew to complaining age – which seemed remarkably early – Adam and Polly complained when they went to the Branns, and Simon and Zoë when they went to the Parsons. The Branns were generous, noisy and slapdash about their Christmases – the Parsons careful, tidy, exact and full of ritual.

‘Couldn’t we just relax and have our own Christmas, in our own home?’ Rupert would lament. ‘Do we have to do all this organising?’ But neither wanted to hurt anyone. It seemed to them that the parents needed them, to add event to their increasingly quiet and suddenly elderly lives.

In those days, when Christmas still started (just) in December, an allocation of money would be made by Rupert, scrupulously administered by Louise. The sum available went up every year, as Rupert’s Own became little by little more prosperous, but every year he had less and less to do with its spending: there was not enough time, not enough energy. ‘I suppose it’s a sensible division of labour,’ said Rupert, sadly, ‘but I do miss all the present-wrapping!’ And the notion somehow grew up between them, that she was the lucky one, because she had the annual making of Christmas, and he had to do without.

While the young Branns and their children spent Christmas Day away from home, Louise would make do not so much with a list as with a master-plan scribbled on the back of an envelope. If total spending was to be £x, then it would be allocated thus:

Branns & Parsons

Branns & Parsons

Children

Children

Each other

Each other

Employees, friends, relatives

Employees, friends, relatives

Sundries, inc. cards, decorations, wrappings

Sundries, inc. cards, decorations, wrappings

The initial division in caring, the allocation of love, its spread across the field of acquaintance, was acknowledged on the chart, and then a money value given to that allocation. How else was it to be done?

As the children grew older, the chart had to be adapted; the in-laws received less, the children more, proportionately.

And in the end, after ten years of marriage, on the eleventh Christmas, she abandoned the chart, and started lists.

That was the year they moved to a big Victorian house with a large, long dining room, and Louise picked up a heavy oak refectory table for almost nothing (in the late sixties, when oak was still unfashionable) and they had an excuse for saying, at last – ‘Look, come to us for Christmas! Everyone!’

And so they did; though the older Branns were to go on alternate years, for a time, to Rupert’s brother Luke, and his wife Veronica, and their two children, Vernon and Lucinda, cousins to Adam, Simon, Polly and Zoë. Louise rather wondered, at the time, at the slight look of relief, not despondency, which crossed the in-laws’ faces at the notion that the tradition was to change.

So, every second year, sitting round the Christmas table, would be:

Louise

Rupert

Adam

Simon

Polly

Zoë

Mr Brann senior

Mrs Brann senior

Mr Parsons senior

Mrs Parsons senior

Nye Evans (Rupert’s partner)

Wendy Evans (Rupert’s partner’s wife, with sclerosis)

A child (from the Give-a-Child-a-Christmas-Scheme centre)

And a few friends or visitors from abroad, or business contacts of Rupert’s who had nowhere else to go and who wanted to experience a proper Christmas.

Around twenty, usually. Never mind. If there was much to be done, there was much to be celebrated!

One dreadful day, when Louise and Rupert had been married for thirteen years, Luke’s wife Veronica woke up to find Luke beside her, dead in bed, and after that she and Vernon and Lucinda came to Christmas dinner too. They never smiled, either, though the years passed and everyone did their best. Veronica would sniff into the stuffing, and Lucinda would mope into the pudding, and Vernon would sulk if he didn’t get one of the silver sixpences, and never give it back if he did get one, in exchange for an ordinary 50p piece, as her own children were expected to; for silver sixpences, with the years, became in shorter and shorter supply, and modern coins tarnished when in contact with the hot, modern, paraffin-washed and dried fruit of the Christmas pudding.

‘The children were like that before Luke died,’ said Rupert in exasperation, one Boxing Day, when the noise of quarrelling and wails rose from the children’s rooms, as the cousins disturbed the delicate equilibrium of post-Christmas relationships. ‘Veronica too. In fact, I daresay that’s why Luke died. He couldn’t stand it a moment longer.’

Everyone tried to like Veronica. They managed to love her, and be protective to her, but like, as everyone knew, was a different matter. With some people, hearts simply sank when they entered a room. And the children seemed to have taken after her. And of course it was only fair to take Veronica, Vernon and Lucinda along on summer holidays too.

Never mind. The family spirit, sheer Christmas energy, swept all before it. Roughs and smooths were ironed out. Mrs Parsons still raised her eyebrows as Mrs Brann raised her glass; Louise learned not to intervene, not to worry; not to try to distract her mother’s attention as her husband (wilfully?) poured his mother yet another glass of brandy.

She learned not to mind her father watching to make sure Rupert wasn’t maltreating her, and his father watching to make sure she wasn’t exploiting him. She learned how to manage the delicate transitions, as both sets of parents little by little relinquished the parental role – asked advice, instead of giving it, unasked.

Louise’s only sister, Madeleine, had left for Australia years back; she’d opted out. She had a career, not a family. Every few years she’d be there, at the Christmas table, blonde and bold and free, with someone different always in tow, an airline pilot or a screen writer. ‘Hard,’ Rupert said, softly, gratefully, his arms round soft, sensible, loving Louise. ‘She’s brittle and hard.’

Madeleine never touched Christmas pudding; pushed the roast potatoes to the side of the plate. In Australia Christmases were salad with cold turkey. Hard to remember this wasn’t universal, cosmic: merely some kind of regional obsession!

There were a couple of bad, bad Christmases, well, you only know you’re happy if you have something extreme to set it against. One, when Rupert was in love with someone else Louise had never met, and never wanted to meet, but was very like her, she’d heard. Rupert exhibited all the symptoms of a husband illicitly in love:

1) taking extra care dressing in the morning.

2) buying new clothes.

3) looking at himself a lot in the mirror.

4) disturbed sleep patterns.

5) intensive fault-finding alternating with maudlin over-appreciation.

6) Radio 2 on the car radio and Vivaldi on the cassette player.

7) detailed and unnecessary accounts of where he’d been and who he’d seen.

8) making love twice as long and twice as often as usual.

She’d sat that out, grimly, and it had all faded away, and just as well, because otherwise she’d have burned the house down and made the children commit mass suicide, and then done it herself, because the family was all of them, and if the all was broken, then they were all as good as dead and the sooner it happened the better. She hadn’t said this at the time: she’d put no pressure on him. If Rupert didn’t know it, what was the point of saying it? But it seemed he did. Rupert had come back, delivered himself again into her safe-keeping. She did not dismay him with reproaches.

And now, of course, later, the children all but grown and gone, the sense of family, as all, had diminished. She was amazed, in retrospect, at the savagery, the extremeness, of her reaction to danger. She’d meant it. She’d have done it. The children had been part of her, then. Not so much now.

And then there’d been the Christmas she’d been in love, distracted, unable to concentrate: alternately singing and weeping about the house, the children following after her, pattering and puzzled. She’d have sacrificed them at the drop of her lover’s hat, run off with him, anywhere, anyhow, just for the feel of his body against hers, to have his mind caught up in her mind, and hers in his – but he hadn’t dropped the hat, in the end. He’d been playing games, teasing his wife.

‘You’ve been using me,’ she wept.

‘Using you?’ He was puzzled. ‘I thought you were using me! Being revenged on your Rupert. Weren’t you? Did you think it was real? Illicit love is never real. That’s why it’s so powerful.’

She was humiliated in the New Year, unhappy until Easter, guilty until Summer, and better and herself by the following Christmas. Did Rupert know? Perhaps not. It had been a busy year, down at Rupert’s Own. Would he have killed himself, if she had gone? Probably not! But the thing was, neither had gone.

And there had been years when one or other of the children had been difficult, had pushed and heaved against the restraining pressure of the warm Christmas blanket. They had various ways of demonstrating their discontent. They would:

a) stay in bed all day

b) stay out all Christmas Eve

c) get drunk or high

d) vomit at the Christmas table

e) quarrel over Christmas TV programmes

f) forget each other’s presents

g) weep all day

h) announce over mince pies: i) loss of virginity, ii) homosexuality, iii) abandonment of education, iv) drug addiction

i) Christmas-out – that is in other people’s houses

j) ask grossly unsuitable friends home

k) be rude to parents in public

But they seldom all did it at once. They acknowledged a kind of family balance, in which any person at any one time could behave very badly or more than one rather badly, so long as everyone else carried on as usual; that is, with a basic politesse, and sense of continued order. And those who erred had still been contained, loved and understood – which of course drove them wilder still, for a time, until reason reasserted itself.

‘Poor things,’ Louise would say to Rupert, and Rupert to Louise, with that strange mixture of complicity, love and resentment with which good parents regard their growing children, ‘all this understanding must be maddening. We must seem like cotton-wool to them. Butt their heads, as they may, all we do is give. They’d be happier, in the short term, with a brick wall to batter at.’ ‘But not in the long term,’ the other would say, and both would nod.

There had been a Christmas or so when she’d been unaccountably irritable and snappy, and had regarded the long rows of expectant faces on either side of the refectory table with less than love. But she had tried, and managed, not to show it. And she had wept and wept one year on discovering that when she handed Rupert his ritual share of the £x (Christmas) in cash, for him to buy her present from him, he had merely put it in the petty cash and sent his secretary out to buy something to its value.

‘You have no idea,’ he said, ‘no idea how busy I am, how worrying everything is. The whole export market is closing down… Exchange rates are so firmly and permanently against us!’

‘Then let’s spend less,’ she begged. ‘We could halve Christmas, we really could, somehow!’

But she could see how difficult it would be, in a world in which everything grew and grew, to offer suddenly less. The children, who had once expected one present each, now felt aggravated if they received less than three or four. It wasn’t that they were greedy, just that the young these days equated giving with love. Give less, and they took it that you loved less, and so construed your explanations and excuses. Not their fault, either, yours, for having got caught up in the world, for being what you were. How could you say to your ageing parents – ‘sorry, cook your own!’ – or to Nye Evans, who now had to cut up his wife’s dinner on the plate, ‘sorry, time’s up!’ or to poor widowed Veronica, ‘Christ! Isn’t it time to stand on your own two feet?’ when her ankles were so obviously and so permanently weak?

They had to reconcile themselves to it all, and pray it would not just end in bankruptcy. Christmas had become Louise’s version of the ‘vicious tax spiral’ of which Rupert had complained – when you had to pay last year’s tax out of this year’s earnings, which were taxed higher than last, and that was that. Do it well this year, and you had to do it better the next. Partly Louise’s own nature, partly the world’s pressure – as in so much else in life, reflected in the way they lived.

1981 was a bad year. The business was in trouble. Not just the export market, but the home market was contracting. There were redundancies, as the business streamlined itself. Rupert was preoccupied, moody, ready to blame anyone for anything, gave up demonstrating his love to her either in bed or anywhere else, fell asleep the minute his head touched the pillow or couldn’t sleep at all and thought it was an indignity to use sex as a soporific (which she construed as him saying to her, if I’m not having a good time, I’ll be damned if you will either) and Zoë had to re-sit her A-levels, and Polly got pregnant and at first wouldn’t have a termination and then suddenly had one much too late, and was ill, and accused Louise of spoiling her life by giving birth to Zoë, so then Zoë was hysterical, and failed more A-levels, and Simon left home too early, and Adam, who had finished college, wouldn’t leave home at all, and Veronica had a nervous breakdown and Vernon and Lucinda had to be made room for, so Zoë walked out and went to live with the Branns senior, whereupon Mr Brann had a mild coronary – or so Mrs Brann claimed – and Zoë said what was the point of education anyway, since everything only ended in unemployment and death, and came home. There wasn’t any time even to make lists of the troubles, so fast did they occur, that Spring.

By the summer holidays everyone had pulled themselves together, of course, and backpacks were filled and friends organised – and off they all went, for once, leaving Louise and Rupert with the wonderful notion that they would have a holiday on their own, for the first time in twenty-one years: except of course then Veronica slipped a disc and so Vernon and Lucinda came along too, to the rented Italian villa. Vernon had a verruca and couldn’t or wouldn’t walk and Lucinda had sunstroke, of the serve-you-right kind. It didn’t really make much difference, Louise thought. To be alone with Rupert suddenly seemed not quite such a good idea. Perhaps he was going mad?

He had the following symptoms:

a) he was careless.

b) he was slovenly in his habits, slopping food and drink and wiping greasy hands on his clothes.

c) he complained of sleeplessness and nightmares.

d) he was rude to guests.

e) he drank too much.

f) he was obsessional – seeing plots where none were.

g) he was for the most part morose, but occasionally noisy and high-spirited.

h) he regarded his wife as his enemy.

i) he went off sex.

A friend, in whom Louise confided her fears – tentatively, for she did not wish to appear disloyal – said ‘Mad? That’s not madness, that’s the male menopause. He’ll grow out of it.’ Another said, ‘Mad? That’s not madness, that’s business worries. Is he impotent too?’ to which Louise could only reply, gloomily, ‘How would I know?’ ‘I expect he is,’ said the friend. ‘Most men of his age are. It’s the women’s movement that’s done it. All those assertive women going about!’

‘I’m not an assertive woman,’ protested Louise. ‘I’m a traditional woman.’

‘Yes, but you’re a busy woman,’ said the friend. ‘God, how busy!’

She wasn’t above accepting an invitation to Christmas dinner, all the same. The Branns’ Christmas was famous.

In the first week of that September, when Louise brought out her file, Rupert said, ‘You can’t be thinking about Christmas already, Louise,’ and Louise did not reply, so he said, ‘Well, I suppose you have to have something to think about.’

In the first week of October Rupert said, ‘Let’s just keep Christmas simple this year, shall we?’ And she did not reply, so he said, ‘But I suppose you’re just not a simple person any more, are you.’

In the second week of October he gave her the Christmas cheque. It was made out for £1800 which represented a twelve per cent increase over the previous year. He peered at it rather curiously, as if it were nothing to do with him, and at her as if she were an oddity.

‘Is that enough?’ he asked.

‘It just about keeps pace with inflation,’ Louise said. Then she said, ‘Take it back. I don’t want anything. There won’t be a Christmas this year.’

‘There has to be Christmas,’ he said, with a kind of heavy meaningless irony. ‘Happy families and all that.’

‘I could sell something,’ she offered, ‘if things are as bad as you say.’

‘Sell what?’ he enquired, and for a moment she thought he was going to hit her.

She made the Christmas lists as usual, very late, and without pleasure.

At the beginning of November he said, ‘If you weren’t such an obsessive hausfrau you could have had a career and kept us both.’

He said it in front of her parents, and she thought perhaps she hated him. She knew it was only temporary, but did not know how to endure until it was all over and Rupert was returned to his normal self. She marvelled at the fragility of the male psyche, which dented so under the impact of material misfortune.

The housekeeping money was transferred from his bank account to hers, each month, as usual: index-linked to keep pace with inflation and with a built-in five per cent annual increase on top of that, which they had decided on and kept to, some fifteen years back. The household was accustomed to a small but steady rise in its standard of living. The price of meat went up, but the size of the steak upon the plate remained much the same, and its quality, if anything, was better.

At the end of November, staring at the piece of fillet steak upon his plate, and watching Polly picking at hers, and Zoë pushing hers away and declaring vegetarianism, and Adam devouring his in three mouthfuls – as do many eldest children, he ate as if terrified someone would snatch the food from his fork – Rupert said:

‘We do live well, don’t we! And all around us are the unemployed and the redundant!’

To which Adam observed, ‘The highest good is to consume, and the second highest good is to employ, which makes you a very good man indeed, Pa,’ and Simon remarked, ‘Eat now, pay later, that’s the only answer to this.’ (He was to the far left, politically, the better to annoy his father.) And Rupert got up and left the table, and thereafter appeared at family meals only sporadically. When Louise asked what was the matter, he replied ‘nothing’.

But Rupert, she knew, was beginning to take the children seriously, as if their phases were them. She saw a real dislike of him dawning in their eyes, or what was worse, a sort of understanding and forgiveness.

‘Mum,’ said Simon, returning blithely from college, ‘don’t take him so seriously. He’s going through a hard time.’

Not take Rupert seriously? How could she not? Were they not, each of them, in the other’s keeping? Now the children seemed to be suggesting she separate herself out from him. How could she? What did they understand, this new, strange, flaring, kindly, idle generation she and Rupert had created?

On December 3rd, on their wedding anniversary, Rupert said, ‘You make such a meal of Christmas. You really shouldn’t. It’s embarrassing to everyone. A file! Who else keeps a Christmas file? Christmas should come from the heart, spontaneously! What do you put in the file?’ She told him, and she went on telling him all night, shaking him awake if he fell asleep; even knowing as she did that he had to be fresh for the next day: that he had a meeting of creditors. She told him about the cards, to begin with.

‘Pages 2–8,’ she said. ‘Cards.’

‘What about Page 1?’ he demanded. ‘You’ve forgotten page 1. Or do you draw Father Christmas on Page 1?’

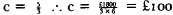

‘Page 1! Page 1 is the overall spending pattern of the Christmas. This year x = £1800. Thank God it’s neatly divisible by six. I need to know how much to spend on cards. Cards is  of sundries. Sundries is

of sundries. Sundries is  of x. That is if x = £1800 and

of x. That is if x = £1800 and  and

and  . Nice and neat, for once! 150 cards or so for £100? You could just about do it. Just.’

. Nice and neat, for once! 150 cards or so for £100? You could just about do it. Just.’

She continued:

1) She made five initial headings, as an aide-mémoir. Family. Friends. Acquaintances. Business. Duty.

2) She entered recipients under appropriate headings.

3) She checked for extra names from previous files of cards sent and received, and entered those.

4) She struck off those who had received cards but not returned them for two years running, exempting the senior citizens and the mentally deranged.

5) She upgraded and downgraded. Acquaintances could become friends: aunts become duty rather than affection.

6) She checked addresses, with reference to the year’s supply of change-of-address cards. Remarkable the number of people whose telephone number one knew but whose address was irrelevant, except at Christmas time.

7) She prepared a section for late cards – unexpected last moment receipts which required immediate response. A small but important section, which would run at 7% of the whole, and had to be prepared for, otherwise the post-Christmas period would be punctuated by telephone calls. Thank-you-for-your-card, I’m-so-sorry – etc.

8) She prepared a section for the children’s cards—

‘Wait a moment,’ he said (he was still at that stage listening), ‘the children have their own Christmas money.’

‘Yes,’ said Louise, ‘but on December 23rd they will remember who they have so far forgotten, in the face of constant reminders, tutors, teachers, music-masters, the parents of friends who have loved them and left them and fed them and housed them during the year; those who have helped and are needed to help again and who will expect cards, and certainly should have them.’

‘You mean like Polly’s abortionist?’

‘Quite so,’ said Louise. She was beyond taking offence. She hurried on to Section 9.

9) She allocated P, SS or CH ratings to all the names on her various lists, actual and estimated. P = posh, SS = serious, CH = cheap and cheerful, and totalled these. Most P’s would be in the business and duty lists, most SS’s in the family, most CH’s in the acquaintance list – but there were several upgraded CH’s every year. The recipients were simply not cheap and cheerful people any more. Now, to find a rough average of what c each P card, each SS card and each CH card could be this year, with c equalling the total of £100, the sums would go like this: no, she would have to refer to the file for the actual workings.

10) E.P.’s warnings would be entered. Early Postings for abroad. Amazing how many people had left, over the years.

Cross-references had of course to be made to sundries.

Means had to be found of displaying received cards: the mantelpiece had long ago ceased to be adequate: string strung from wall to wall was unsatisfactory as the cards tended to drift towards the dip in the middle: lately, fortunately, wire card stands had started to appear in the shops, each holding about twenty cards, and these could be stood about here and there in the house. They had a tendency to topple, but it was the best solution she could find. Which cards were to take pride of place where was always tricky: people judged you on that, too. If you put the posh ones too much in evidence, you were boasting: if you put the humble ones forward you were being overly sentimental. Of course, anyone who called liked to see their own card well displayed, and unannounced callers were frequent at Christmas time. You just had to predict them. You needed a lot of sherry too, but that was part of the food and drink section in the file, and she was still only on cards.

She found it best, she told her husband, to make separate expeditions to the shops for her various Christmas purposes, otherwise she ended up forgetting things. She would make one or two journeys for the cards, another for the ingredients for the Christmas pudding, another for decorations and wrappings, another for sundries, three usually for presents, and four carloads of food shopping. Drink, fortunately, was delivered, as were hired glasses. But you had to get in early with an order for those, at Christmas time. More advance planning. If they were giving a party, she would make a separate expedition for the food required for that: two parties over the Christmas season, two expeditions, two separate, and if possible remote, cupboards, to store the food in, once bought. The children and their friends, late home one night and hungry, could eat party tit-bits for fifty and still be looking for more.

But she digressed; Christmas was full of digressions. All she could really say was, one learned seasonal tricks from seasonal experience.

She didn’t, she went on, like cutting down on wrappings. Experience proved you always ran out on Christmas Eve, no matter how early you opened the Christmas file, how efficiently you planned. She did try, in the very early hours of Boxing Day, when she was clearing up and the rest of the house slept happily, and boozily, in the knowledge of another good family Christmas spent, to smooth and fold and save at least some of the expensive paper for the following year, but she usually found herself too tired to care: she would just go through the house, abandoning all discrimination, stuffing black plastic sacks with the litter left by generosity and joviality. Twenty-one people to Christmas, each of whom would give a present to everyone else, meant 21 × 20 presents, which meant 420 discarded pieces of paper, not to mention tags, bows, and the debris of crackers. Everyone loved crackers, of course. She had a special page in the file for crackers. Somehow, even so, she always managed to forget the crackers. The children were neurotic about crackers – always had been. Sibling rivalry somehow focused on crackers. Crackers were a winner-takes-all situation. Adam, who had after all suffered three psychic blows, as three times his position in the family had been usurped, had to hold back tears whenever Simon, Polly or Zoë bettered him in cracker-pulling. The only solution was lots and lots of crackers, to make them nothing special. She’d tried no crackers, but Mr Brann had said Christmas isn’t Christmas without crackers, did you forget, Louise, good heavens – you’re usually so organised about Christmas, Louise, meaning but you have nothing else to do, Louise, but buy crackers...

‘You’re getting upset,’ he said. They were in bed. She talked on. He had this meeting in the morning. He wanted to sleep. ‘No, I’m not upset,’ she said. ‘I’m just telling you about Christmas. I’m still on cards: we’ve just had a minor digression into wrappings and crackers. I haven’t started on presents, let alone food, let alone drink.’

She was still talking at four in the morning; he had managed to fall asleep. When he woke, with the dawn, she was describing the unthawing of the turkey and the search for a big enough roasting pan, not too big for the oven, and the hope that the unending roll of foil would not in fact choose that day to end.

Rupert said, as he woke, ‘If Luke was alive, he might have been able to help me,’ and Louise hit him. He hit her back and they rolled about in the bed, as they had so often in love and laughter, biting, scratching, snarling and hurting. It had never happened before, never.

Rupert went to work without breakfast. His cheek was scored by her nails. She had a sprained wrist.

‘A wonderful way to meet my creditors,’ he observed as he got into the Jaguar. It was not a new car, but it was splendid. Crimson, with real red leather upholstery.

‘Really, creditors?’

‘You just spend your Christmas money,’ he said. ‘Open your file, and have a happy Christmas.’ She would have slashed his tyres, and possibly his throat, but he left smartly, before she could. He did not deal properly with the creditors – a little more enthusiasm, a little more energy and perhaps he would have carried the day. As it was, he failed.

When he returned that evening she was glad to see him, and he to see her. The habits and affections of years can stand up to a little truth-telling. He could complain, with fairness, that her inability to enjoy the good things he gave her – that is, the family Christmas – undermined the point of his very existence, and she, equally fairly, that he failed to appreciate how much that existence depended on her martyrdom, but each complaint held the other in equilibrium.

Christmas came and went.

In February the factory was closed: in March the Official Receiver was called in. It was amazing how quickly things moved, once they’d begun. The house was put up for sale, and sold, with contents, at a knock-down price. Rupert was morose and drank a great deal: he suffered from nightmares. He slipped a disc, and had to lie on his back in his parents’ home while Louise found somewhere to live, and sorted the children out. Polly moved in with her boyfriend; Zoë, who was still at school, moved in with the Parsons grandparents, and for the first time started working for her exams, as if realising that if she didn’t, she’d have to live with them for ever. Veronica, who seemed greatly invigorated by Rupert’s and Louise’s misfortunes, suddenly got herself a job and a new flat, and said Adam and Simon could stay with her whenever they wanted, and she’d do Christmas that year, for everyone.

By October Rupert and Louise were living in a very small terraced house in an outer suburb, just where the city drifted off into countryside. There was no chance of Rupert finding work for a year or so – until his back was better and his mental state more positive. He was now a declared bankrupt, which meant that he could not sign cheques or engage in business activities. After many visits from social workers and much dealing with bureaucracy, Louise managed to arrange for him to get welfare payments, on which they lived. He did not like going out: he thought people would stare at him. He did not want the children to visit, to witness his failure, his downfall. ‘What do you mean, failure?’ she would cry out in irritation. ‘It isn’t failure, it’s the way the world is now. There are three million unemployed, apart from anything else, and most of those don’t even have bad backs.’

‘If you don’t know what failure means, you’re a fool,’ he said. He was not pleasant to her. Much of the time he seemed to actively hate her. He slept as far away from her as he could, at night. She told herself it was because they were so close to each other, he couldn’t distinguish which was him and which was her, and since he hated himself must seem to hate her. It was temporary, she told herself. It would pass. She remained as pleasant, and as positive, and as bracing as she could.

The winter closed down. Christmas was coming. She had saved a box of Christmas decorations, from the Fall – as she described it – but she didn’t put them up. What was there to celebrate?

‘Veronica has asked us for Christmas dinner,’ she said, at the beginning of December.

‘We can’t afford the fares,’ he said. She knew he meant that he could not bear the humiliation of sitting at someone else’s table, and not the head of his own. She did not press the point. They did not go to Veronica’s. Some thirty Christmas cards came through their letterbox that year, most of them with kindly notes inscribed, ‘Just a greeting! Don’t bother to respond!’ Why had she never thought of that? Why, because to accept is so much more difficult than to give. She had never realised that. She began to be sorry for the recipients of her generosity in the past.

It snowed a little. The ground crackled agreeably underfoot. A branch nailed itself, with frost, against the chilly bathroom windowpane. They both stood and admired it.

‘It’s so simple and so beautiful,’ said Louise. ‘Chinese!’

‘Japanese,’ he corrected her. He smiled, she thought for the first time since they had come to live here. He rubbed his hands together.

‘Let’s light a fire,’ he said. ‘Get warm. We can gather sticks in the lane.’ He built a great mound of dead wood in the back garden, gritting his teeth against the pain in his back. Louise wondered if the wood was not somehow someone else’s property, but kept her thoughts to herself.

A very heavy parcel arrived from Madeleine in Australia. When opened, it proved to be a food parcel. It contained Australian tinned and dried fruits and jams, and some kangaroo soup and some dried baby shark.

It was Louise’s turn to weep and weep from the shame and desolation of it all, and to rage at him, and her moral collapse seemed to make him better. They were regaining some kind of equilibrium. He dried her tears and was fond of her again.

‘Now you know what I feel,’ he said. He made love to her that night, and very frequently thereafter.

‘We have time to develop the art,’ he said. ‘At last.’

Welfare provided a ten-pound Christmas bonus that year and she spent it on a chicken, some potatoes, some mushrooms (luxury!) and a Christmas pudding from Woolworth’s. The Brann parents sent two bottles of wine, the Parsons parents a kitchen gift-set of washing-up bowl, brushes and so forth, in red plastic. The children appeared with various inappropriate but touching gifts on Christmas Eve, guilty about the proper Family Christmas, now at Veronica’s, but unwilling – ‘thank God,’ Rupert said – to renounce it, and somehow feeling the better and the more united, for their parents’ reduced circumstances.

Christmas Day dawned to a clear blue sky and the crackle of frost. They lay in bed for a long time, and presently he got up and put the chicken in the oven. He bent to light it without wincing. His back was much better.

‘I suppose,’ he said, ‘now we’re back to the beginning, there’s nothing to stop us starting all over again. But let there be no more lists.’