Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents

Getting Oriented | Top Attractions | Worth Noting

Updated by James O’Neill

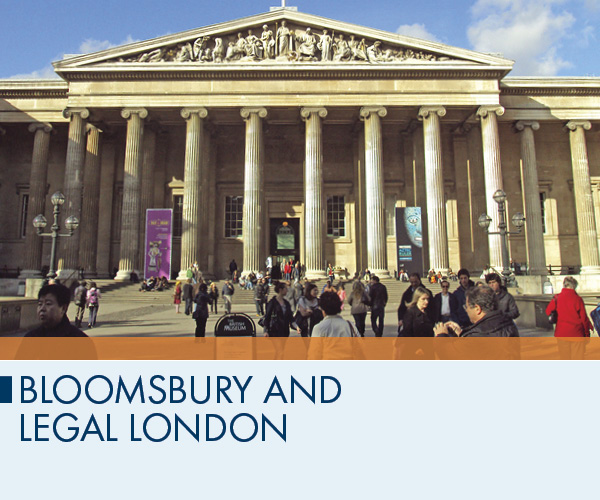

London can be a bit schizophrenic: Bloomsbury is only a mere couple of hundred yards from fun-loving, hedonistic Soho. Best known for the famous flowering of literary-arty bohemia in the early 20th century as personified by the Bloomsbury Group, the area encompasses the British Museum, the British Library, and the University of London. But don’t let all this highbrow talk put you off: filled with beautiful historic buildings, Bloomsbury is simply a delightful part of the city in which to walk and explore.

Fundamental to the region’s spirit of open expression and scholarly debate is the legacy of the Bloomsbury Group, an elite corps of artists and writers who lived in this neighborhood during the first part of the 20th century. Gordon Square was at one point home to Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes (both at No. 46), and Lytton Strachey (at No. 51). But perhaps the best-known square in Bloomsbury is the large, centrally located Russell Square, with its handsome gardens. Scattered around the University of London campus are Woburn Square, Torrington Square, and Tavistock Square. The British Library, with its vast treasures, is a few blocks north, across busy Euston Road.

The area from Somerset House on the Strand, all the way up Kingsway to the Euston Road, is known as London’s Museum Mile for the myriad historic houses and museums that dot the area. Charles Dickens Museum, where the author wrote Oliver Twist, pays homage to the master, and artists’ studios and design shops share space with tenants near the bright and modern British Museum. And guaranteed to raise a smile from the most blasé and footsore tourist is Sir John Soane’s Museum, where the colorful collection is a testimony to the namesake founder.

Bloomsbury also happens to be where London’s legal profession was born. In fact, the buildings associated with Holborn were some of the few structures spared during the Great Fire of 1666, and so the serpentine alleys, cobbled courts, and historic halls frequented by the city’s still-bewigged barristers ooze centuries of history. The massive Gothic-style Royal Courts of Justice ramble all the way to the Strand, and the Inns of Court—Gray’s Inn, Lincoln’s Inn, Middle Temple, and Inner Temple—are where most British trial lawyers have offices to this day.

Getting Oriented

Top Reasons to Go

Take a tour of “Mankind’s Attic”: From the Rosetta Stone to the Elgin Marbles, the British Museum is the golden hoard of booty amassed by centuries of the British Empire.

The Inns of Court: Stroll through the quiet courts, leafy gardens, and magnificent halls that comprise the heart of Holborn—the closest thing to the spirit of Oxford London has to offer.

Time travel at Sir John Soane’s Museum: Quirky and fascinating, the former home of the celebrated 19th-century architect is a treasure trove of antiquities and oddities.

Treasures at the British Library: In keeping with Bloomsbury’s literary traditions, this great repository shows off the Magna Carta, a Gutenberg Bible, Shakespeare’s First Folio, and other masterpieces of the written word.

Charles Dickens Museum: Pay your respects to the beloved author of Oliver Twist at his former residence.

Feeling Peckish?

The Betjeman Arms.

The Betjeman Arms, inside St. Pancras International’s wonderfully Victorian station (shining star of the Harry Potter films), is the perfect place to stop for a pint and grab some traditional pub fare. Perched above the tracks of the Eurostar Terminal, the view of the trains will keep you entertained for hours. | Unit 53, St. Pancras International Station | N1C 4QL | 020/7923–5440.

The Hare and Tortoise Dumpling & Noodle Bar.

This bright café serves scrumptious Asian fast food. A favorite with students, thanks to huge portions, reasonable bills, and all-natural ingredients. | 15–17 Brunswick Shopping Centre,

opposite the Renoir Cinema, Brunswick Square,

Bloomsbury | WC1N 1AF | 020/7278–9799.

Getting There

The Russell Square Tube stop on the Piccadilly line leaves you right at the corner of Russell Square.

The best Tube stops for the Inns of Court are Holborn on the Central and Piccadilly lines or Chancery Lane on the Central line.

Tottenham Court Road on the Northern and Central lines is best for the British Museum.

Once you’re in Bloomsbury, you can easily get around on foot.

Making the Most of Your Time

Bloomsbury can be seen in a day, or in half a day, depending on your interests and your time constraints.

If you plan to visit the Inns of Court as well as the British Museum, and you’d also like to get a feel for the neighborhood, then you may wish to devote an entire day to this literary and legal enclave.

An alternative scenario is to set aside a separate day for a visit the British Museum, which can easily consume as many hours as you have to spare.

It’s a pleasure to wander through the quiet, leafy squares at your leisure, examining historic Blue Plaques or relaxing at a street-side café. The many students in the neighborhood add bit of street life.

Top Attractions

British Library.

This collection of around 18 million volumes, formerly in the British Museum, now has a home in state-of-the-art surroundings. The library’s greatest treasures are on view to the general public: the Magna Carta, a Gutenberg Bible, Jane Austen’s writings, Shakespeare’s First Folio, and musical manuscripts by G.F. Handel as well as Sir Paul McCartney are on display in the Sir John Ritblat Gallery. Also in the gallery are headphones with which you can listen to pieces in

the National Sound Archive (it’s the world’s largest collection), such as the voice of Florence Nightingale and an extract from the Beatles’ last tour interview. Marvel at the six-story glass tower that holds the 65,000-volume collection of George III, plus a permanent exhibition of rare stamps. On weekends and during school vacations there are hands-on demonstrations of how a book comes together, and the library frequently mounts special

exhibitions. If all this wordiness is just too much, you can relax in the library’s piazza or restaurant, or take in one of the occasional free concerts in the amphitheater outside. | 96 Euston Rd.,

Bloomsbury | NW1 2DB | 0870/7412–7332 | www.bl.uk | Free, donations appreciated, charge for special exhibitions | Mon. and Wed.–Fri. 9:30–6, Tues. 9:30–8, Sat. 9:30–5, Sun. and bank holiday Mon. 11–5 | Station: Euston, Euston Sq., King’s Cross.

Fodor’s Choice |

British Museum.

With a facade like a great temple, this celebrated treasure house, filled with plunder of incalculable value and beauty from around the globe, occupies a ponderously dignified Greco-Victorian building that makes a suitably grand impression. This is only appropriate, for inside you’ll find some of the greatest relics of humankind: the Parthenon Sculptures (Elgin Marbles), the Rosetta Stone, the Sutton Hoo Treasure—almost everything, it seems, but the Ark of the Covenant.

The place is vast—there are 2 ½ miles of floor space inside, split into nearly 100 galleries—so arm yourself with a free floor plan directly as you go in or they’ll have to send our search parties to rescue you.

The three rooms that comprise the Sainsbury African Galleries are a must-see in the Lower Gallery—together they present 200,000 objects, highlighting such ancient kingdoms as the Benin and Asante. The museum’s focal point is the Great Court, a brilliant modern design with a vast glass roof that reveals the museum’s covered courtyard. The revered Reading Room has a blue-and-gold dome and hosts temporary exhibitions. If you want to navigate the highlights of the almost 100 galleries, join the free eyeOpener 30- to 40-minute tours by museum guides (details at the information desk).

The core collection began when Sir Hans Sloane, physician to Queen Anne and George II, bequeathed his personal collection of antiquities to the nation. It grew quickly, thanks to enthusiastic kleptomaniacs after the Napoleonic Wars—most notoriously the seventh Earl of Elgin, who acquired the marbles from the Parthenon and Erechtheion in Athens during his term as British ambassador in Constantinople. Here follows a highly edited résumé (in order of encounter) of the British Museum’s greatest hits: close to the entrance hall, in Room 4, is the Rosetta Stone, found by French soldiers in 1799, and carved in 196 BC by decree of Ptolemy V in Egyptian hieroglyphics, demotic (a cursive script developed in Egypt), and Greek. This inscription provided the French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion with the key to deciphering hieroglyphics. Also in Room 4 is the Colossal statue of Ramesses II, a 7-ton likeness of this member of the 19th dynasty’s (ca. 1270 BC) upper half. Maybe the Parthenon Sculptures should be back in Greece, but while the debate rages on, you can steal your own moment with the Elgin Marbles in Room 18. Carved in about 400 BC, these graceful decorations are displayed along with a high-tech exhibit of the Acropolis. Be sure to stop in the Enlightenment Gallery in Room 1 to explore the great age of discovery through the thousands of objects on display. Also in the West Wing is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—in fragment form—in Room 21: the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos. The JP Morgan Chase North American Gallery (Room 26) has one of the largest collections of native culture outside North America, going back to the earliest hunters 10,000 years ago. Next door, the Mexican Gallery holds such alluring pieces as the 15th century turquoise mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, the Mexican Fire God and Turquoise Lord. The Living and Dying displays in Room 24 include Cradle to the Grave, an installation by a collective of artists and a doctor displaying more than 14,000 drugs (the number estimated to be prescribed to every person in the U.K. in his lifetime) in a colorful tapestry of pills and tablets.

Upstairs are some of the most popular galleries, especially beloved by children: Rooms 62–63, where the Egyptian mummies live. Nearby are the glittering 4th-century Mildenhall Treasure and the equally splendid 8th-century Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo Treasure (with magnificent helmets and jewelry). A more prosaic exhibit is that of Pete Marsh, sentimentally named by the archaeologists who unearthed the Lindow Man from a Cheshire peat marsh; poor Pete was ritually slain in the 1st century, and lay perfectly pickled in his bog until 1984. The Korean Foundation Gallery (Room 67) delves into the art and archaeology of the country, including a reconstruction of a sarangbang, a traditional scholar’s study. | Great Russell St., Bloomsbury | WC1 | 020/7323–8000 | www.britishmuseum.org | Free; donations encouraged | Galleries Sat.–Thurs. 10–5:30, Fri. 10–8:30. Great Court Sat.–Thurs. 9–6, Fri. 9 – 8.30 | Station: Russell Square, Holborn, Tottemham Court Rd.

Fodor’s Choice |

Charles Dickens Museum.

This is the only one of the many London houses Charles Dickens (1812–70) inhabited that is still standing, and it would have had a real claim to his fame in any case because he wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby and finished Pickwick Papers here between 1837 and 1839. The house looks exactly as it would have in Dickens’s day, complete with first editions, letters, and a tall

clerk’s desk (where the master wrote standing up, often while chatting with visiting friends and relatives). Down in the basement is a replica of the Dingley Dell kitchen from Pickwick Papers. A program of changing special exhibitions gives insight into the Dickens family and the author’s works, with sessions where, for instance, you can try your own hand with a quill pen. Visitors have reported a “presence” upstairs in the Mary Hogarth bedroom,

where Dickens’s sister-in-law died—see for yourself! Christmas is a memorable time to visit, as the rooms are decorated in traditional style: better than any televised costume drama, this is the real thing. The museum also houses a shop and café. | 48 Doughty St.,

Bloomsbury | WC1N 2LX | 020/7405–2127 | www.dickensmuseum.com | £7 | Daily 10–5; last admission 4:30 | Station: Chancery La., Russell Sq.

Fodor’s Choice |

Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Guaranteed to raise a smile from the most blasé and footsore tourist, this museum hardly deserves the burden of its dry name. Sir John (1753–1837), architect of the Bank of England, bequeathed his house to the nation on condition that nothing be changed. We owe him our thanks because he obviously had enormous fun with his home: in the Picture Room, for instance, two of Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress series are among the paintings on panels that

swing away to reveal secret gallery pockets with even more paintings. Everywhere mirrors and colors play tricks with light and space, and split-level floors worthy of a fairground fun house disorient you. In a basement chamber sits the vast 1300 BC sarcophagus of Seti I, lighted by a domed skylight two stories above. (When Sir John acquired this priceless object for £2,000, after it was rejected by the British Museum, he celebrated with a three-day party.) The elegant,

tranquil courtyard gardens with statuary and plants are open to the public, and a below-street-level passage joins two of the courtyards to the museum. Because of the small size of the museum, limited numbers are allowed entry at any one time, so you may have a short wait outside. On the first Tuesday of the month, the museum opens for a special candlelit evening from 6 to 9 pm, but expect to wait in a queue for this unique experience. | 13 Lincoln’s Inn

Fields,

Bloomsbury | WC2A 3BP | 020/7405–2107 | www.soane.org | Free, Sat. tour £5 | Tues.–Sat. 10–5; also 6–9 on 1st Tues. of month | Station: Holborn.

Worth Noting

Gray’s Inn.

Although the least architecturally interesting of the four Inns of Court and the one most damaged by German bombs in the 1940s, Gray’s still has romantic associations. In 1594 Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors was performed for the first time in the hall—which was restored after World War II and has a fine Elizabethan screen of carved oak. You must make advance arrangements to view the hall, but the secluded and spacious gardens, first planted

by Francis Bacon in 1606, are open to the public. | Gray’s Inn Rd., Holborn | WC1R 5ET | 020/7458–7800 | www.graysinn.org.uk | Free | Weekdays noon–2:30 | Station: Holborn, Temple.

Lincoln’s Inn.

There’s plenty to see at one of the oldest, best preserved, and most attractive of the Inns of Court—from the Chancery Lane Tudor brick gatehouse to the wide-open, tree-lined, atmospheric Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the 15th-century chapel remodeled by Inigo Jones in 1620. Visitors are welcome to attend Sunday services in the chapel; otherwise, you must make prior arrangements to enter the buildings. | Chancery La.,

Bloomsbury | WC2A 3TL | 020/7405–1393 | www.lincolnsinn.org.uk | Free | Gardens weekdays 7–7, chapel weekdays noon–2:30; public may also attend Sun. service in chapel at 11:30 during legal terms | Station: Chancery La.

Royal Courts of Justice.

Here is the vast Victorian Gothic pile of 35 million bricks containing the nation’s principal law courts, with 1,000-odd rooms running off 3½ miles of corridors. This is where the most important civil law cases—that’s everything from divorce to fraud, with libel in between—are heard. You can sit in the viewing gallery to watch any trial you like, for a live version of Court TV. The more dramatic criminal cases are heard at the Old Bailey. Other sights are the

238-foot-long main hall and the compact exhibition of judges’ robes. | The Strand,

Bloomsbury | WC2A 2LL | 020/7947–6000 | www.hmcourts-service.gov.uk | Free | Weekdays 9–4:30 | Station: Temple.

Temple Church.

Featuring “the Round”—a rare, circular nave—this church was built by the Knights Templar in the 12th century. The Red Knights (so called after the red crosses they wore—you can see them in effigy around the nave) held their secret initiation rites in the crypt here. Having started poor, holy, and dedicated to the protection of pilgrims, they grew rich from showers of royal gifts, until in the 14th century they were charged with heresy, blasphemy, and sodomy, thrown into

the Tower, and stripped of their wealth. You might suppose the church to be thickly atmospheric, but Victorian and postwar restorers have tamed the air of antique mystery. Nevertheless, this is a fine Gothic-Romanesque church. | King’s Bench Walk, The Temple,

Bloomsbury | EC4Y 7BB | 020/7353–8559 | www.templechurch.com | £3 | Check website for details | Station: Temple.

University College London.

The college was founded in 1826 and set in a classical edifice designed by the architect of the National Gallery, William Wilkins. In 1907 it became part of the University of London, providing higher education without religious exclusion. The college has within its portals the Slade School of Fine Art, which did for many of Britain’s artists what the nearby Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (on Gower Street) did for actors. The South Cloisters

contain one of London’s weirder treasures: the skeleton of one of the university’s founders, Jeremy Bentham, who bequeathed himself to the college. Legend has it that students from a rival college, King’s College London, once stole Bentham’s head and played football with it. Whether or not the story is apocryphal, Bentham’s clothed skeleton, stuffed with straw and topped with a wax head, now sits (literally) in the UCL collection. Be sure to take a look at the stunning

Gotham-esque Senate House on Malet Street.

Petrie Museum. If you didn’t get your fill of Egyptian artifacts at the British Museum, you can see more in the neighboring Petrie Museum, accessed from the DMS Watson building. The museum houses an outstanding, huge collection of fascinating objects of Egyptian archaeology—jewelry, toys, papyri, and some of the world’s oldest garments. | 020/7679–2884 | www.petrie.ucl.ac.uk | Free, donations appreciated | Tues.–Sat. 1–5; closed over Christmas and Easter holidays | Malet Pl., Bloomsbury | WC1E 6BT | Station: Euston Sq., Goodge St.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Table of Contents