2

The Benedictine Rule and Its Longevity

Benedict as “Textual Trace”

In the last decade of the sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) wrote a text in Rome that would soon be comparable to only a few others in its importance for shaping the development of monastic life in the West. The text concerns the origins of Benedictine life.

In four books entitled Dialogues on the Life and the Miracles of the Italian Fathers (Dialogi de vita et miraculis patrum italicorum),1 Gregory aimed to prove that the Italian peninsula had nurtured an asceticism equal in standing to that of the East.2 One of its protagonists was Benedict, from the central Italian city of Nursia (today Norcia), who for decades was the abbot of a monastery on Monte Cassino. The pope, as he admitted, did not know the abbot personally but had only heard of him through contemporary witnesses. Among them were even two of Benedict’s successors as abbot. Gregory seems to have seen in Benedict—who was “blessed in grace as well as in name” (Dialogues 2. Prologue)3—a particularly powerful model character, one worthy of the entire second book of his Dialogues.

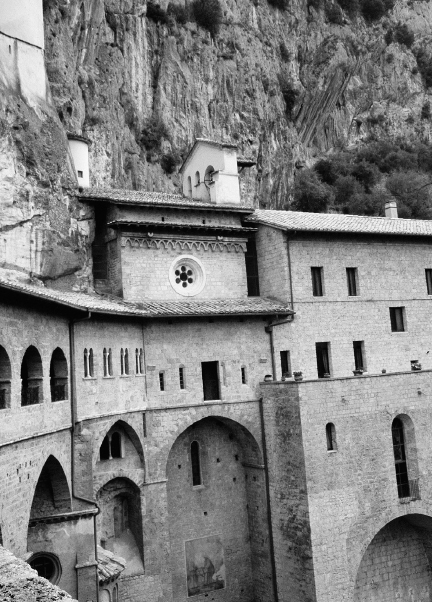

The Abbey San Benedetto near Subiaco. It is also called Sacro Speco, the Holy Cave. Here, according to Pope Gregory I, was Benedict’s first residence.

Gregory’s treatment of the life and work of an abbot who had previously inspired no written record should not be understood as a biography in any modern sense. The work was instead intended to convey an ideal image of an ascetic and a charismatic leader of a monastic community. Consequently, the author was less interested in historical facts than in their power to serve as examples. These bore witness to the abbot’s divine gifts, to the sanctity of his conversion and his ability to work miracles, and to his extraordinary power to communicate norms and values.

At the beginning of the text stands Benedict’s turn from the world of late antique Rome, which to him now seemed to be completely corrupt: “But as he saw many sink into the abyss of vice, he pulled back the foot that he had placed on the threshold of the world, so that he himself would not also fall into that horrible abyss, had he tasted something of worldly knowledge” (Dialogues 2. Prologue). His resolve led him first to the loneliness of a hidden cave near Subiaco on the slopes of the Apennines, where he aimed to live “alone in himself, under the eyes of the heavenly watchman” (Dialogues 2.3). But after a time he left this dwelling (over which was eventually built the imposing abbey of San Benedetto, which still stands today) to settle in the valley and to try to live a life of asceticism in community. He took over the leadership of one monastery, where he was almost poisoned by his own monks, and thereafter founded his own. Finally he set out from that region, heading to the south, and settled at Monte Cassino, where with his followers he established a monastery on the site of a ruined ancient temple.

Clearly Gregory’s text stylized Benedict’s life to this point as the narrative of his gradual steps toward redemption in order to bring him all the more powerfully to his destination. The story goes on to emphasize how Benedict set about fighting with the devil to establish his community, and how through his miracles he established not only its inner stability but also its social moorings in the world around it. The text then places special emphasis on the fact that Benedict wrote a rule there, one that “was excellent in its measured discernment [discretio], illuminating in its exposition.” “If one should want to learn of his life and his nature more precisely,” Gregory wrote, “he can find it all in the prescriptions of this rule, whose discipline he taught through deeds. For the holy man could not teach in any other way than the way he lived” (Dialogues 2.36).

Benedict reached the pinnacle of his ascent (a worldly ascent, if considered superficially, but in reality a spiritual one) one night as he stood high above in the window of his tower, in prayer. There, as the text relates (Dialogues 2.35), he saw a light as bright as day, and “the whole world” stood before his eyes, “drawn together as in a single ray of sunshine.” The scope of his life expanded from the narrows of the first cave near Subiaco to encompass the breadth of the whole world, and even at his death that same ascension was rendered visible one last time: where once his body had been hidden in the walls of caves, separated from all, he now died at Monte Cassino supported by his crowd of followers, lifted high and with his hands raised to heaven.

With this symbolically rich performance, the stage was set for Benedict’s future veneration not only as the paternal leader of a community but also, far beyond that, as a mediator between the narrowly bound earthly matters of this world and God’s boundlessness in heaven. That kind of message was about far more than any mere historiographical effort to communicate the facts. Without question it provided the foundation for a veneration of Benedict that later earned him the designation “Father of the West” or, as the 1964 papal expression put it, the “Patron of Europe.”4

All the more striking is that such a grand impact depends on a single text. What Gregory’s contemporaries knew of Benedict, what many generations afterward knew, and indeed what we know of Benedict today we know from this one text alone. That includes even Benedict’s very existence, since had Gregory not written a second book of the Dialogues, no “Benedictine” monasticism could ever have been established. From the point of view of historical criticism, therefore, the text itself becomes a problem.5 What, after all, guarantees its accuracy? For those in search of historical facts, the panegyric of the text both clouds the subject matter and in equal measure idealizes it in ways that move beyond history. Gregory provided no chronology anchored in specific years, because he needed nothing of that sort for his purpose. The dates of Benedict’s life must be extrapolated from other events or people known from the historical record—480 for his birth, 529 for the foundation of the community at Monte Cassino, and 547 for his death.

Gregory’s text was an orphan in its day, moreover, not only because it stood as a single textual witness.6 Behind it stood not even a contemporary physical monument that might have spoken to the abbot’s institutional impact. Gregory himself in fact mentions that the monastery at Monte Cassino had since Benedict’s time been destroyed by the Lombards (Dialogues 2.17)—an event that would seem to be well placed in the year 577, when forces led by Duke Zotto laid waste to wide stretches of the countryside, but which must date in any case to some point in the broad span of time between the 570s and 580s. A much later and uncertain source, the history of the Lombards written by Paul the Deacon in the 780s, suggests that some of the surviving monks fled to Rome. At the time of the composition of the Dialogues, no reliable trace of Benedictine life was to be found anywhere.

Any later impact Benedict might have had as a model of ascetic leadership in a community of monks thus clearly depended on how widely Gregory’s Dialogues were received. Gregory did nothing worthy of mention to publicize the text, though his name alone carried sufficient renown. The first mention of the work appeared in 613/14, far to the north among the Franks, in an explicit citation. In the course of the seventh century the work then came to be read all over southern and western Europe. Its reading thus allowed Benedict to become quite a familiar figure from an early date,7 and yet it took until the first decade of the eighth century—so far as we know—for anything about Benedict as a saint worthy of veneration to be written down outside of the Dialogues, in an entry in the calendar of the Northumbrian and Frisian missionary Willibrord.8

The Rule of Saint Benedict

Benedict’s actual appearance took place in a different way. It came about earlier, and in the end it had more of an impact than the hagiography. In the year 625 Venerandus, abbot of the Provençal monastery of Hauterive (Alta Ripa), wrote to the bishop of Albi that his community followed the Rule sancti Benedicti abbati Romensis—of the “Roman” abbot Saint Benedict.9 The text of the Rule itself prepared the way for the growth of the reputation of Benedict and the power of Benedictine monasticism.

Gregory had written that the Rule of Saint Benedict was filled with the spirit of discernment—discretio. The oldest surviving witness of the text that coalesced under the name of Benedict is from early eighth-century England, followed by a somewhat different version from the first third of the ninth,10 commissioned by Charlemagne. The text, along with others before it, is in fact shaped by the ideal of discernment (discretio).11 Through his normative power, the leader of the community—the abbot—was obligated to righteousness: “He must know,” says the text of the Rule, “what a difficult and demanding burden he has undertaken: directing souls and serving a variety of temperaments, coaxing, reproving and encouraging them as appropriate.” He must “accommodate and adapt himself to each one’s character and intelligence” (RB 2.31-32). He is to take heed of “this and other examples of discretion, the mother of virtues” (RB 64.19).12

These principles guided the allotment of necessities among all in common, the distribution of clothing, food, and drink or the assignment of work on particular tasks, the care of the old, children, and the ill, or the carrying out of punishment. The justification was found in this sentence from the Rule: “Everything he teaches and commands should, like the leaven of divine justice [divina iustitia], permeate the minds of his disciples” (RB 2.5). In this way the abbot was positioned to serve as a bridge between the monastery’s immanence and divine transcendence. Only by virtue of this double relationship was the abbot to be understood as the representative of Christ in the monastery, as the very beginning of the Rule emphasizes. The same relationship explains both the tremendous responsibility of the abbot with respect to his community and the fact that he alone is responsible for them before God.

The Rule is a spiritual text. Its opening words—“Listen, my son, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart” (RB Prol. 1)—indicate an inner, spiritual listening, one that should make the “heart wide” and that should make it possible to “run on the path of God’s commandments,” in “the inexpressible delight of love” (RB Prol. 49). The Rule’s admonitions, such as “Let us open our eyes to the divine light and let us hear with a startled ear what the voice of God calls us and urges us to do: ‘Today, if you hear his voice, do not let your heart be hardened’” (RB Prol. 9-10), are directed to those who strive for the highest possible perfection of their souls, which they seek to embed within the divine order.

Yet the Rule is also an organizational text. It assumes that the individual remains imperfect, and therefore endangered, and that a life in community, in a monastery cut off from the world, is the best safeguard in the struggle for perfection. In that respect the monastery is to be understood as a “school for the Lord’s service” (RB Prol. 45) and is presented as a “workshop” (RB 4.78) in which, with the help of the “tools for good works” (RB 4, heading), the soul is shaped for God. In this school every desire for the love of God and neighbor would be established, as well as the avoidance of moral vices like pride, contentiousness, and idleness.

But beyond that, certain monastic virtues of ascetic life are also important: to love fasting, to chastise the body, to deny fleshly desires, to practice silence, and to renounce personal property. Common prayer and liturgical celebration, common eating, sleeping, and manual labor establish the rhythms of the day. Regarding the last of these, the Rule says, “When they live by the labor of their hands, as our fathers and the apostles did, then they are really monks” (RB 48.8). This sentence had revolutionary potential in the best sense, because it reinterpreted the meaning of manual labor; once an activity that in the ancient tradition was appropriate for a slave but not for a free man, here it appeared as an activity that allowed access to heaven. Work was ascesis, and it had the power to ennoble all Christians, regardless of their status.

The Rule lays out in painstaking detail the norms that are to guide all of these relationships, and it thereby lays claim to the whole person, both inwardly and outwardly. At the same time it is a pragmatically oriented text that is able to organize daily life. As a set of legal instructions,13 it regulates the acceptance of new members, the division of labor among the offices of the monastery, the administration of economic resources, the duties of almsgiving to the poor at the gate, the provision of clothing and tools, and so on. It seeks to forestall deviance, sets out the conditions through which guilt can be acknowledged and atoned for, and lays out guidelines for punitive measures ranging from corporal punishment to exile from the community for serious infractions. The Rule envisions an enclosed community, one whose economy and organization are autarchic and one largely untouched by the interference of outside ecclesiastical authorities. The local bishop is to be called in only when the community’s priest has blatantly failed or when the abbot has tolerated moral decline.

The text of the Rule itself rests on the foundations of what was already a rich monastic tradition. It depends above all on the so-called Rule of the Master,14 composed around 500, a text whose strict asceticism and discipline it somewhat relaxed, and it also uses (as the text itself reveals) the “Rule of our Holy Father Basil” (d. 379), thus bringing together the intellectual legacy of Eastern and Western monasticism. It was thus probably the Rule’s humane balance between strictness and mercy, as well as its calculated syncretism, that especially contributed to the excellent quality of the text’s content and thus to its success. The Rule was exemplary in its moderation, seeking to bring spiritual challenges into harmony with the limits of bodily strength, so that the ascetic world of the monastery might be bearable—not a prison, but a joyful place whose inhabitants were set free to pursue their ultimate end.15

And yet it can nowhere be clearly shown that this fascinating text is identical to that which Gregory mentions in his Dialogues. When the pope wrote that the Rule written by Saint Benedict was shaped by discretio, that in itself was no sufficient basis for forming a judgment about it; the same could have been said, for example, of the Rule of Cassian.16

Even if Gregory made it clear that Benedict taught exactly as he lived, the Rule could thereby only give information about the way of life of its author, and not vice versa. The text offers not the slightest hint of biographical evidence. The attribution of the text to a Benedict appears quite early, however, and presumes as accepted fact that the Benedict of the Dialogues and the Benedict of the Rule are the same person. The fact that this Benedict was named the “Roman abbot” early on by Venerandus (in the case noted above), and more frequently still in later decades, was—according to the evidence of the Dialogues—historically inaccurate; questions thus arise about whether Gregory’s text had been understood very well.

Yet the Rule’s very orientation toward Rome—probably because the text was first identified in a remark by a Roman bishop—contributed to its success among those who were at the time predisposed to give it a warm reception: the Franks. In the seventh century a network of Gallo-Frankish patrons gathered around the Merovingian court were committed to founding and supporting monasteries; they had a clear interest in promoting the Rule of Saint Benedict, not least because the text was understood to be “Roman” in a normative sense.17 Benedict’s Rule thus gained in authority and at the same time presented itself as an ideal bridge to Rome, home to the prince of the apostles.

A growing interest in Rome and the life of its monasteries is also discernible in England. From there the Northumbrian abbot Benedict Biscop (629–690), among others, had several times traveled through the western Frankish kingdom and to Rome, in order to study monastic life and its texts in general. He also encountered the Rule of Saint Benedict in Lérins and then introduced it (in the form of a hybrid text) in his monasteries, Wearmouth and Jarrow, on the Northumbrian coast.18 It is also possible that his travels produced what remains the oldest surviving manuscript of the Rule of Saint Benedict, found today in Oxford (Bodleian Library, Hatton 48). At times Benedict Biscop was accompanied by his friend Wilfrid (ca. 634–709/10), a monk from the community of Lindisfarne.19 After Wilfrid had returned to his Northumbrian home in 661, he received from Ealhfrith, the son of the king, the abbey of Ripon (today in North Yorkshire). There he introduced both the Roman Rite and the Rule of Saint Benedict, albeit probably in a mixed form, with regional customs. This signaled the start of what would be a strong retreat of the Irish-Scottish traditions of monastic life in central England—a development only strengthened by the subsequent decrees of an Anglo-Saxon council held in Whitby in 664 under the growing influence of southern England.20

The Career of Benedict and His Rule

This phase of the “discovery” of Benedict’s Rule, which lasted well into the eighth century, fell within a multifaceted and lively epoch of Latin monasticism.21 It was an age shaped by the brisk pace of new foundations, especially those of kings and the upper nobility. Some significant examples, among many, include the male monastery of Corbie in the Somme Valley and the women’s monastery of Chelles near Paris, both founded by the Frankish queen Balthild (d. 680),22 and the women’s monastery of San Salvatore in Brescia, established in 753 by the Lombard king Desiderius.23 Also characteristic for the time, however, were the important missionary efforts that had their origins in the Irish, and later in the Anglo-Saxon, ideal of peregrinatio noted above and that found both organizational and spiritual manifestation in the founding of numerous new monasteries. Early examples include the foundations of the missionary bishop Pirmin, for example, the monastery of Reichenau, founded in 724.24 Women’s monasticism also found notably strong expression in the form not only of women’s communities but also in the rise of double monasteries,25 in which women and men lived separately yet together as one community. In England, Whitby,26 founded in 657, stood out as an example here, and in France the monastery of Remiremont in Alsace, founded in 620.27

In this era of new beginnings, the text of the Rule that was coming together under the name of Benedict began its career as part of the so-called mixed rules—that is, the textual products of a selective reading of a variety of surviving rules by various authors, shaped not least by local customs or the decisions of local abbots. Normative guidelines that one might call a “religious rule” were at that time not bound to unalterable texts.

One widespread combination blended the Rule of Saint Benedict with that of the Irish missionary Columbanus, who (as was noted above) had founded the monasteries of Luxeuil and Bobbio. Already under the second successor to Columbanus at Luxeuil, Waldebert (629–679), the community began to depart from strict adherence to Columbanus’s norms, taking up additional stipulations from the Benedictine rule.28 Such changes spread quickly. Evidence suggests that already by around 640, life at the new abbey of Fleury (today Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire) was lived “according to the Rule of most holy Benedict and lord Columbanus,”29 and that this normative guide was quickly passed on to Lérins, the renowned ancient Gallic monastery off the coast of Provence. The focal point of the spread was in Gaul, where up to the end of the seventh century, at least in the northern regions, almost every monastery was more or less strongly influenced by the Benedictine rule. Adding nuance to the pattern is the fact that new rules were also composed at the time using Benedict’s text. So, for example, Donatus, bishop of Besançon from 624–660 and strongly influenced by Luxeuil, composed a rule for nuns from texts of Caesarius of Arles and Columbanus as well as from the Benedictine rule.30 An anonymous author (probably from Luxeuil) was similarly inspired, composing a “rule for virgins” that survives as regula cuiusdam ad virgines, a text strongly (though not exclusively) based on the Rule of Saint Benedict.31

Yet for all of the places where the Benedict of the Dialogues had been active, early on he could be remembered nowhere—there was no Benedictine life in either Subiaco or Monte Cassino. Already in the second half of the seventh century it was believed that Benedict’s body had come to rest in the monastery of Fleury on the Loire. Italy seems to have simply forgotten the “humble provincial abbot”32 who had been stylized in the Dialogues as a saintly model.

The situation changed dramatically in 717. Looking back at around the end of the eighth century, the monk Paulus Diaconus wrote in his History of the Lombards33 that Petronax, a leading citizen of the city of Brescia, had moved first to Rome and then—at the insistence of Pope Gregory II (715–731)—to the “fortress” of Cassino, “to the holy body of the blessed father Benedict.” There he came upon a few simple men who chose him as their master (Senior). After attracting more monks, Petronax came to see himself as compelled to begin a life in community and to found the monastery anew, “under the yoke of the holy rule and according to the model of blessed Benedict.” Somewhat later Petronax is said to have received from Pope Zachary (741–752) the more substantial collection of books that was so essential for monastic life, among them the rule that the blessed father Benedict had supposedly written with his own hand. A genuine monastery had now been established, a visible and fixed monument, where previously there had been only the letters of a written report. That it should have turned out this way was certainly because of the personal commitment of Gregory II, who consciously sought to attach himself to the pontificate of his namesake and predecessor—and who wanted to develop good relations with the Franks in order to establish a certain counterbalance to the political and religious influence of the Byzantines.

A succession of visitors quickly began to arrive from the Frankish kingdom. Particularly frequent as guests were the students and associates of Winfrid Boniface of Wessex, whom Gregory II had consecrated as a missionary bishop. Among the first of those, arriving around 730, was Willibald, later bishop of Eichstätt, who had already lived according to the “institution of the regular life of holy Benedict” and who now passed on his experience to the new community at Monte Cassino. In 747 and 748 Sturmius followed, the abbot of Fulda, the community he had founded under the direction of Boniface, which already lived exclusively according to the Rule of Saint Benedict.34 That rule had certainly found in Boniface an early supporter with widespread influence. Under his direction, in 742/43 a reform synod had prescribed that the Rule of Saint Benedict should be the only authoritative guide for all Frankish monasteries.35

And yet something was still missing on Monte Cassino: the body of Benedict. Here too Pope Zacharias offered help, together with another esteemed guest at Monte Cassino: Carloman, the now resigned brother of Pippin, who with the aid of Pope Zacharias had become the Frankish king. In 750/51, Zacharias gave Carloman a letter to take with him to the Frankish kingdom. The letter asked that Benedict’s body (which was firmly believed to be at Fleury) be brought back to Monte Cassino. The effort was not very successful: Monte Cassino eventually received only a few bones. In his history (cited above), Paul the Deacon later offered the community the consolation that because no one would have been able to steal any decaying body parts immediately after Benedict’s death, they were surely still to be found at the place where he had died. Consequently, Paul said, he could rightly assert—as cited above—that Petronax “was drawn to the holy body of the blessed father Benedict.”

More and more Monte Cassino grew “into the role of a monastic model.”36 Abbot Theodomarus (778–797) soon sent a lengthy letter to Count Theodoric, a relative of Charlemagne, in which he wrote out and explained the customs of Monte Cassino for the use of certain brothers in Gaul.37 Charlemagne himself visited the abbey in 787, on the occasion of a campaign against the Duchy of Benevento, and asked for a copy of the version of the Rule that Pope Zachary had brought there. Charlemagne, who was generally concerned for the norma rectitudinis, for ordering his kingdom according to what was right, valued what he saw as the unadulterated text—a text that in his eyes, of course, stood as the autograph it was claimed to be. As the so-called Aachener Normalkodex, this version of the Rule lived on.

The Second Benedict and the Reform of the Frankish Monasteries

Yet the spread of the text of the Rule, and above all the recognition of the text as the normative standard for monastic life, unfolded more slowly than decrees—for example, the synod of 742/43 noted above—might suggest. Without doubt, in view of the challenge of holding the empire together, the Carolingians had a political interest in having the most uniform rule possible for their monasteries. The Benedictine rule, for both its inner balance and—as has been emphasized—its supposedly Roman origins, seemed best suited in this regard. The decrees of the synods and imperial diets presumed from 789 forward that monastic life should be exclusively Benedictine. Delegates to the diet held in Aachen in autumn of 802 brought with them from all parts of the empire letters reporting how matters stood regarding the recognition and implementation of the Benedictine rule.38

In light of their scandalous deficiencies, all monasteries were now strictly commanded to order their liturgical practices according to this rule. The monasteries, each one calling on local traditions foundational to their identity, resisted strongly. The renowned community of Corbie, for example, followed customs that had nothing to do with either the text or the spirit of the Benedictine rule, and at Saint Gall and Reichenau the story was no different. Moreover, especially during the reign of Charlemagne, other renowned male and female monasteries—for example, Saint Denis near Paris, Saint Bénigne in Dijon, Saint Victor in Marseille, Chelles near Paris, and Nivelles in Brabant—gave up their monastic observance and turned to the easier way of life lived by canons and canonesses.

At least in some regions, the measures of 802 were not without results. Archbishop Leidrad of Lyon (d. 813), for example, undertook a massive attempt to enforce the Rule of Saint Benedict in his diocese.39 But the broader breakthrough of enforcement came under the son of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, who embraced comprehensive reforms on the political, social, and ecclesiastical levels in order to ensure the unity of his kingdom. One of his most important supporters was Benedict of Aniane (ca. 750–821),40 born as Witiza, son of the Count of Maguelonne. Already in the late eighth century he had shaped the life of the southern French monastery of Aniane, which he had founded, into a strict Benedictine community guided by a blended, especially stern observance based on particular prescriptions from Basil and Pachomius.

Later he sent monks from Aniane to reform other monasteries across Aquitaine and Languedoc, gave these communities the Rule of Saint Benedict along with other written customs (consuetudines), and visited them. From these emerged a loose, nonhierarchical congregation of Benedictine houses. In 814 Benedict of Aniane was called to the side of Louis the Pious, and in 815/16, after a stay in the Alsatian monastery of Maursmünster, with Louis’s support he founded the abbey of Inden (later Kornelimünster) near Aachen. He developed that community into a kind of center for training personnel for other monasteries that wanted to embrace the observance of the Benedictine rule.

The remark in the Rule of Saint Benedict (61.2) that each monastery had a certain “local custom” (consuetudo loci) was for Benedict of Aniane the key provision that allowed him to assume a twofold normative guide, one based on the Rule as well as on custom—and thus to develop, on the basis of a single valid rule, a single custom for the entire kingdom. In a way consistent with the motto “one rule and one custom” (una regula et una consuetudo)41 and using Inden as a model for monastic life—with the help of royal assurance of immunity from the interference of other sovereigns, assurance of free abbatial elections, and assurance of royal protection even in matters that did not concern royal monasteries—Benedict sought to enforce a uniform monastic life across the Frankish kingdom.

In an unprecedentedly radical way—though the results only emerged after a long process—three synods (held at Aachen in 816, 817, and 818/19) commanded monastic communities to adhere exclusively to the dictates of the Benedictine rule. And as an aid to putting the new policy into practice, Benedict of Aniane himself authored a series of consuetudines that served as a kind of guide to implementation. Their guidelines were equally valid for both male and female monasteries, as the anonymous biographer of Louis the Pious emphasized: “the uniform and unchanging custom of life according to the rule of holy Benedict was carried to the monasteries, to men as well as to holy female nuns” (sanctis monialibus feminis).42

The decrees were broadcast throughout the kingdom by royal ambassadors—missi. Yet Benedict of Aniane admittedly did not use every opportunity to achieve as one possible aim of his measures the institutional incorporation of every monastery in the empire under a common Benedictine observance. The one binding consuetudo was insufficient, not least because it had not been established in a strictly monolithic form. There was no comprehensive cohesion within prayer confraternities, as might have been established according to the Irish/Anglo–Saxon mode,43 nor were the monasteries subordinated legally and hierarchically to Benedict of Aniane’s leadership, since he was concerned on principle to preserve the autonomous position of each monastery in the Benedictine sense. He sought much more to ensure the continuity of his reforms through the power of the Frankish ruler and the efficacy of his legal ordinances, which were aimed at the establishment and preservation of monasteries guided by the Benedictine rule and by a “regular” abbot (abbas regularis).

At the same time, and motivated by the same idea of the political unity of the realm, in 816 the Synod of Aachen reformed the clergy by giving them their own way of life alongside the monks—the ordo canonicus. Building on regulations that Bishop Chrodegang of Metz44 (ca. 715–766) had already developed for clergy in his diocese, as well as on the relevant decrees of councils held under Charlemagne (especially that of the year 794), the synod completed a “book on the establishment of the canons” (Liber de institutione canonicorum).45 It set out in detail how the clergy was to lead a life in community—a vita communis—in an enclosed, monastic space, whether within a bishop’s court or as an independent community; it further required that a praepositus—a “superior”—should stand at the head of such communities (called “foundations”), and finally that the canons were to have a common refectory and dormitory and were to pray and work together.

It can rightly be said that the intention of this legislation was thus to “monasticize” the clergy, but with two very important differences: there was no life-long commitment to membership, and the use of property was allowed. In all events, since from the time of the Carolingian reforms the vita canonica had always also been understood as the vita apostolica, the personal poverty of the now-regulated lives of the canons nevertheless remained one of their most essential founding ideals. This set of tensions would eventually nurture a number of later conflicts, each of which would inspire further efforts at reform.

The synods made parallel efforts to regulate the lives of canonesses—women who lived together in communities but who were not bound to a strict vow of poverty or lifelong membership.46 The 816 synod promulgated the Institutio Sanctimonialium, a statute that regulated the life in community of these women. Here too, as among the men, the daily life of community with its obligations of prayer, meals, and sleep in common rooms stood in the forefront. According to this legislation, canonesses were obligated to obedience to an abbess, though they could retain their own personal property (including the ownership of land), employ servants, and use private rooms for retreats within their strictly guarded enclosures. Social differences and sensibility to differences in rank were not denigrated, though no member was to be disadvantaged because of them.

The nature of the surviving sources, however, allows for neither proof of the immediate realization of the Institutio or even for the possibility of making a clear distinction over the next two centuries between which houses were occupied by canonesses and which by nuns of some form of Benedictine observance—in later terminology, whether the community was a “foundation” (Stift) or a monastery. The boundaries were fluid. This was especially true for the great wave of new women’s communities established from the ninth to the early eleventh century in the region of the duchy of Saxony—a wave that began in 800 with Herford, reached its first high point with the establishment of Essen before 850 and Gandersheim in 852, and then continued in the following century with Quedlinburg in 936 and others, eventually encompassing some sixty-four houses.47

Yet in the era that followed the Synod of Aachen—an era that saw the severe endangerment of monastic life across wide stretches of Europe through the destructive power of external invasions—the lifestyle of the canon provided for many monastic communities a kind of refuge from the strictness of their rules. Since Aachen’s prescriptions for canons or canonesses had been seen as less strict than the requirements for monks and nuns, from the eleventh century on they would become the object of strong attacks from reformers of the vita religiosa. As a consequence it would not be long before at least the elite among the clergy, with the support of the church hierarchy, actually embraced the monastic way of life and remembered the text that had not yet been rediscovered in the time of the Aachen Synod: the Rule of Augustine, with its command of personal poverty in keeping with the spirit of the apostolic community.48

But because monastic life in Western Christendom was so deeply embedded in the politics of the Frankish kingdom, it began slowly to change. Because of those political connections, Benedictine life—though with certain delays here and there—finally broke through against all of its competitors some 350 years after Gregory the Great told of its beginnings in the Dialogues and retained its dominant position for another 250 years. But the same politics also ensured that the monastic world became more strongly bound to earthly affairs and that it had to be acknowledged to a significant degree as both a provider of services and a source of power. By the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious at the latest, a political and also a politicized monastic life had fully developed.

Although Louis the Pious may also have seen his monastic reforms as a matter of serving the reputation (honor) of the church and of raising it up (exaltatio),49 monasteries had long since become notable centers of economic activity and focal points for the development of infrastructure. For the eastern regions of the empire, it is enough to cite by way of example older foundations such as Reichenau (founded in 724), Fulda (founded in 744), Tegernsee (founded in the middle of the eighth century), Lorsch (founded in 764), and the women’s community on the Odilienberg in Alsace (founded in the seventh century). But the same was true for more recent foundations like Corvey (founded, after its predecessors, in 822).50

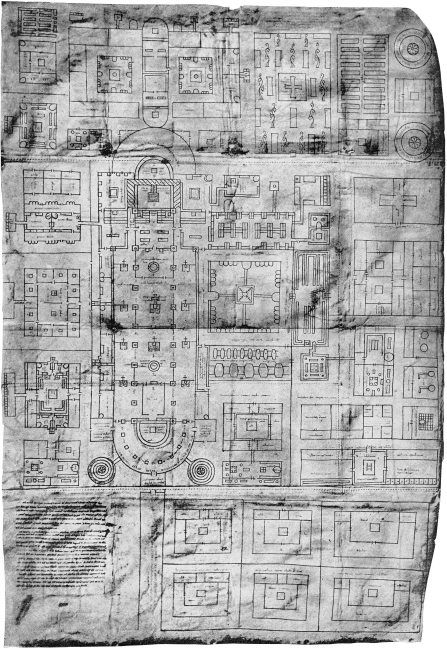

All of these communities enjoyed extensive landed estates. Fulda, founded in 744 by Sturmius under the direction of Winfrid Boniface, by 800 had estates and monastic cells that reached as far to the south as the Danube.51 Such wealthy monasteries, moreover, were a European-wide phenomenon, within what were at that time the boundaries of Christendom. In Italy, for example, Nonantola was founded in the middle of the eighth century, Pomposa was founded in the middle of the ninth century, and Farfa,52 the imperial abbey in the Sabine country, was founded at the beginning of the eighth century, its wealth soon so enormous that the abbey had its own tax-exempt commercial ship. An idealized plan of the monastery of Saint Gall (presumably drawn up between 820–830 at Reichenau) reveals the new, now architecturally tangible schemes of spatial organization that, though absent from the Rule of Saint Benedict, were being imagined for such massive abbeys.53 Centered on the church building, the plan was arranged to ensure economic independence, to meet the needs of the abbey’s guests (from the most renowned to the simple pilgrim), to ensure the integrity of its insulation from the world (only the abbot, by means of his own house, served as a link to the outside), and to provide for medical care and the education of the next generation. The layout thereby corresponded to the essential decrees of the reform synod at Aachen.

Charlemagne in particular—and his successors followed his lead—knew how to enlist monasteries to meet his kingdom’s various needs, whether in technical matters concerning the logistics of provision, in military affairs, or for the formation of a political elite. Most of these monasteries had been granted immunity and were thereby protected from interference by royal officials. They had also been granted sovereign jurisdictional rights. Many of them, moreover, because they had been handed over (traditio) to the ruler by a noble founder, had in fact become royal monasteries and thereby enjoyed both the king’s protection and the right of free abbatial election.54 Nearly all of them were also endowed with rich agricultural estates and their appropriate dependent farmers (socmen). The varying degrees of attention these monasteries received were thus not always oriented toward the realization of monastic ideals but rather toward political goals, dynastic ties, and the potential for service to the king (servitium regis), which included the obligation to provide lodging and provision for the king and to provide a military contingent drawn from the nobility tied to the household.55 More and more the abbots were able to articulate their concerns (these, too, often shaped by political interests) at the imperial synods. They were at the same time entangled more tightly than ever in the political struggles and rivalries of the day.

And yet this structure certainly had two sides. Charlemagne and his successors had already shown their great interest in upholding proper discipline and piety in the monastery. Encyclicals (capitularies) issued at imperial diets and the decrees of synods all spoke the same language: monasteries were (or at least should be), as it were, extraordinary places for connecting to God, places where one could expect the establishment of peace, the stability of sound royal rule, and protection from overpowering enemies, whether from hell or on earth, as well as the gift of good harvests and reward for good deeds on earth and in heaven. An old obligation of the monastery, well established by long tradition, now came to the fore: to “pray for the salvation of the emperor and his sons and the stability of the empire,” as was still said in 819, in the time of Louis the Pious.56

These external expectations about the proper relationship to God corresponded to a development within the monastery that was of overwhelming importance: the clericalization of the monks. Chapter 62 of the Rule of Saint Benedict had spoken of only a single priest in the monastic community, one whose task was to ensure against violations of obedience and to enforce the discipline of the Rule. Monks were laymen. Of course there were always a few among them who had been ordained as priests. But by the eighth and ninth centuries, this situation had fundamentally changed: members of the monastic community were now overwhelmingly also priests. It did not come about as a matter of pastoral care for the monks’ neighbors, because even when monasteries were responsible for parishes, those parishes were in principle cared for by secular priests who had been assigned to them. “Ordination was the crowning and the completion of spiritual life” and “a call to the holy altars,”57 in whose service one was more likely to merit a hearing before God than in the corporate prayer of the community.

This plan of an ideal monastery (112 x 77.5 cm) was drawn up in the first third of the ninth century on the island of Reichenau. It is preserved in the library of Saint Gall Abbey. See also the web-based project at www.stgallplan.org.

Moreover, an office had in the meantime emerged that was to protect a monastery from unjust interference, to represent it in legal matters, and to dispense justice in its name within the boundaries of its immunities: the office of the advocate (derived from the Latin advocatus), held by a secular lord who was at first usually appointed by the king.58 This office too was intended to free the monastic community from worldly matters and thereby allow monks to focus on spiritual concerns. Yet from the beginning the danger was clear: the advocates themselves would strive, in the interests of advancing their own power, to assert lordship over the monasteries, especially when the advocate was also—as was usually the case—the owner of the monastery or when (as was more and more the case from the ninth century on) the office of the advocate became inheritable within a particular noble family, thereby depriving the monastery of the possibility of itself choosing the advocate.

How strongly monasteries, despite all of their inner discipline, were shaped by the world around them—a world for whose stability the monasteries prayed in their own self-interest—became clear at the latest by the time of the Carolingian decline, when it did so in a remarkably dramatic way. The external attacks of the Northmen, Magyars, and Saracens, against whom the Frankish kings at first offered little resistance, began in the ninth century and reached far into the tenth. These attacks had fatal consequences for monastic life in central Europe. The Magyars destroyed a number of monasteries along and south of the Danube in the first half of the tenth century; in 926 they advanced as far as Saint Gall and pillaged it. In 883 the Saracens had already destroyed the abbey of Monte Cassino, so that the mountain remained a wasteland for decades. The Saracens also plundered the Burgundian royal abbey of Saint Maurice on Lake Geneva in 939, and in 940 they destroyed the Alpine monastery of Disentis.

The Northmen, too, left behind scorched earth. Most monasteries near the Atlantic coast—whether in Britain or on the continent—were abandoned, and many women’s houses retreated to seek new settlements farther east. So, for example, the members of Saint-Saveur (Redon), in the diocese of Vannes, resettled in the area of Auxerre in Burgundy in 921. But it was no more secure there than in its original site, as the two-time capture of the Eifel community of Prüm in 882 and 892 reveals, along with the plundering of the nearby monastery of Disibodenberg, also in 882—a community that would endure yet another round of destruction at the hands of the Avars in the first half of the tenth century. No cycle of wartime atrocities ever had such a cataclysmic impact on Europe’s landscape of monasteries as this series of annihilations.

The weakening of centralized royal power, and the breakdown of order within the empire that followed, had a destructive impact on the life of the monastery. The consequence, especially in the western Frankish kingdom, was the widespread transfer of the royal monasteries’ rights of ownership into the hands of the nobility, which thereby often led to a corrosion of monastic discipline, to exploitation, and to the ruin of the monasteries’ economic capacity. What the destructive force of external enemies could not accomplish, the private feuds and plundering expeditions of the regional nobility did, in a time whose transformations of power had brought about something close to anarchy.59

A serious consequence of this general political circumstance then appeared in the western Frankish kingdom: the renewed fragmentation of monastic life into a multiplicity of consuetudines, for which the word Benedictine was little more than a label. Countless monasteries lost their populations entirely and transformed themselves into canonries without even attempting to uphold the standards of the Aachen decrees.60 Especially disadvantageous in that day, moreover, were the nearly unbroken traditions of the proprietary church, through which (as has been noted) monasteries became a marker of a founder’s wealth and through which the protection and defense of a monastery’s rights were subordinated to the interests of a secular (though also often an ecclesiastical) owner—including the appropriation of the office of abbot by a noble layman, who was empowered by rights of ownership to dispose of the material resources of the community and who installed a prior to take care of religious matters. All of these changes fundamentally contradicted the spirit of the Rule of Saint Benedict, to be sure, but they need not in principle have had a negative impact on the welfare of a community. For, as has often been shown, even a “lay abbot”61 could take good care of both the spiritual and the material affairs of his monastery. In a time of generally weakened structures of order and values, however, such a betrayal of the actual spirit of monastic life had a powerfully threatening potential. It is thus revealing that when in 909, the provincial Synod of Trosly near Laon explicitly recognized laity as the owners of monasteries, it nevertheless emphatically noted that in view of the resulting abuses one could no longer speak of the condition of the monasteries, but only of their decline. To drive home the point, the synod noted that lay abbots (abbates laici) now lived in the monasteries with their wives, sons, and daughters, their vassals and hunting dogs.62

__________

1 Umberto Moricca, ed., Gregorii Magni Dialogi libri IV (Rome: Tipografia del Senato, 1924).

2 On early religious life in Italy, see Georg Jenal, Italia ascetica atque monastica. Das Asketen- und Mönchtum in Italien von den Anfängen bis zur Zeit der Langobarden (ca. 150/250–604), 2 vols. (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1995).

3 Here and below, translated from Dialogorum Libri IV de miraculis Patrum Italicorum, vol. 2, Kommentar zur “Vita Benedicti”: Gregor der Große: das zweite Buch der Dialoge—Leben und Wunder des ehrwürdiger Abtes Benedikt, ed. Michaela Puzicha (St. Ottilien: EOS, 2008). For an English translation, see John Zimmerman, Saint Gregory the Great: Dialogues (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1983).

4 Filips de Cloedt, ed., Benedictus. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Abendlandes (Geneva: Weber, 1980); Adalbert de Vogüé, “Benedikt von Nursia,” Theologische Realenzyklopädie (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1980), 5:538–49. See James G. Clark, Benedictines in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2011).

5 Note here the controversial arguments of Johannes Fried, Der Schleier der Erinnerung (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2004); Joachim Wollasch, “Benedikt von Nursia. Person der Geschichte oder fiktive Idealgestalt?” Studien und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Benediktinerordens und seiner Zweige 118 (2007): 7–30. On the same issue see also Gert Melville, “Montecassino,” in Erinnerungsorte des Christentums, ed. Christoph Markschies and Hubert Wolf (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2010), 322–44.

6 On the following remarks concerning Benedict’s impact, see in more detail Melville, “Montecassino.”

7 Adalbert de Vogüé, “Benedikt von Nursia,” Theologische Realenzyklopädie 5:549.

8 Pius Engelbert, “Neue Forschungen zu den ‘Dialogen’ Gregors des Großen. Antworten auf Clarks These,” Erbe und Auftrag 65 (1989): 376–93, here 381.

9 Joachim Wollasch, “Benedictus abbas Romensis. Das römische Element in der frühen benediktinischen Tradition,” in Tradition als historische Kraft, ed. Joachim Wollasch (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1982), 119–37; Pius Engelbert, “Regeltext und Romverehrung. Zur Frage der Verbreitung der Regula Benedicti im Frühmittelalter,” in Montecassino della prima alla seconda distruzione, ed. Faustino Avagliano (Montecassino: Pubblicazioni Cassinesi, 1987), 133–62.

10 Georg Holzherr, ed., Die Benediktsregel: Eine Anleitung zu christlichem Leben (Fribourg: Paulus, 2007), 37.

11 Adalbert de Vogüé, Reading Saint Benedict, CS 151 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1994). See also the concise treatment of Mirko Breitenstein, “Die Regel—Lebensprogramm und Glaubensfibel,” in Macht des Wortes, ed. Gerfried Sitar and Martin Kroker (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2009), 23–29.

12 Rudolf Hanslik, ed., Benedicti Regula (Vienna: Hoedler-Pichler-Tempsky, 1977); Latin/German trans. Die Benediktusregel (Beuron: Salzburger Äbtekonferenz, 1992); numerical annotations indicate chapter and line. English translations here from RB 1980: The Rule of St. Benedict in English, ed. Timothy Fry, et al. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981).

13 Uwe Kai Jacobs, Die Regula Benedicti als Rechtsbuch (Cologne: Böhlau, 1987).

14 La Règle du maître, ed. and trans. Adalbert de Vogüé (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1964); Die Magisterregel: Einführung und Übersetzung, trans. Karl Suso Frank (St. Ottilien: EOS, 1989).

15 Gregorio Penco, “Monasterium—Carcer,” Studia monastica 8 (1966): 133–43.

16 See chap. 1, p. 17.

17 Wollasch, “Benedictus abbas Romensis”; Engelbert, “Regeltext und Romverehrung.”

18 David Knowles, The Monastic Order in England (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1950), 21–22.

19 David Peter Kirby, ed., Saint Wilfrid at Hexham (Newcastle upon Tyne: Oriel Press, 1974).

20 Sarah Foot, Monastic Life in Anglo-Saxon England c. 600–900 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 24ff.

21 Prinz, Frühes Mönchtum, 263–92.

22 Jacques Dubois, “Sainte Bathilde et les fondations monastiques à l’époque mérovingienne,” Chelles notre ville, notre histoire. Bulletin de la société archéologique et historique de Chelles, New Series 14 (1995/96): 283–309.

23 Giancarlo Andenna, “San Salvatore di Brescia e la scelta religiosa delle donne aristocratiche tra età longobarda ed età franca (VIII–IX secolo),” in Female vita religiosa between Late Antiquity and the High Middle Ages: Structures, Developments and Spatial Contexts, ed. Gert Melville and Anne Müller (Berlin: LIT, 2011), 209–33.

24 Arnold Angenendt, Monachi peregrini (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1972); Peter Classen, ed., Die Gründungsurkunden der Reichenau (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1977).

25 Prinz, Frühes Mönchtum, 658–63.

26 Dagmar Beate Baltrusch-Schneider, “Die angelsächsischen Doppelklöster,” in Doppelklöster und andere Formen der Symbiose männlicher und weiblicher Religiosen im Mittelalter, ed. Kaspar Elm and Michel Parisse (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1992), 57–79; Isabelle R. Odile Charmantier, “Monasticism in Seventh-Century Northumbria and Neustria. A Comparative Study of the Monasteries of Chelles, Jouaree, Monkwearmouth/Jarrow, and Whitby,” PhD dissertation, University of Durham, 1998.

27 Michel Parisse, ed., Remiremont, l’abbaye et la ville (Nancy: Université de Nancy II, 1980).

28 Prinz, Frühes Mönchtum, 270–72.

29 Maurice Prou and Alexandre Vidier, Recueil des chartes de l’abbaye de Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, 2 vols. (Paris: Picard, 1900–1907), 1:1, 5.

30 Michaela Zelzer, “Die ‘Regula Donati,’ der älteste Textzeuge der Regula ‘Benedicti,’” Regulae Benedicti Studia 16 (1987): 23–36.

31 Albrecht Diem, “Das Ende des monastischen Experiments. Liebe, Beichte und Schweigen in der Regula cuiusdam ad virgines (mit einer Übersetzung im Anhang),” in Melville and Müller, Female vita religiosa, 80–136.

32 Vogüé, “Benedikt von Nursia,” 5:549.

33 Paulus Diaconus, Historia Langobardorum, ed. Georg Waitz, MGH, Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum (Hannover: Hahn, 1878), 6:230–31. On the later history of Monte Cassino see the detailed treatment of Melville, “Montecassino.”

34 Dieter Geuenich, “Bonifatius und ‘sein’ Kloster Fulda,” in Bonifatius—Leben und Nachwirken, ed. Franz J. Felten, et al. (Mainz: Gesellschaft für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte, 2007).

35 Winfried Hartmann, Die Synoden der Karolingerzeit im Frankenreich und in Italien (Paderborn: Schöningh, 1989), 47–63.

36 Pius Engelbert, “Regeltext und Romverehrung,” 133–62, here 157.

37 “Theodomari abbatis Casinensis epistola ad Theodoricum gloriosum,” ed. Jacob Winandy and Kassius Hallinger, in Initia consuetudinis Benedictinae. Consuetudines saeculi octavi et noni, ed. Kassius Hallinger, CCM 1 (Siegburg: Schmitt, 1963), 125–36.

38 MGH, Concilia aevi Karolini [742–842], Teil 1 [742–817]: 230.

39 Otto Gerhard Oexle, Forschungen zu monastischen und geistlichen Gemeinschaften im Westfränkischen Bereich (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1978), 134–57.

40 Emmanuel von Severus, “Benedikt von Aniane,” in Theologische Realenzyklopädie (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1980), 5:535–38; Pius Engelbert, “Benedikt von Aniane und die karolingische Reichsidee: Zur politischen Theologie des Frühmittelalters,” in Cultura e spiritualità nella tradizione monastica, ed. Gregorio Penco (Rome: Pontificio Ateneo S. Anselmo, 1990), 67–103; Walter Kettemann, “Subsidia Anianensia. Überlieferungs- und textgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur Geschichte Witiza-Benedikts, seines Klosters Aniane und zur sogenannten ‘anianischen Reform,’ ” PhD dissertation, Duisburg, 1999; Online: http://duepublico.uni-duisburg-essen.de/servlets/DocumentServlet?id=18245.

41 On the following, see Josef Semmler, “Benedictus II. Una regula—una consuetudo,” in Benedictine Culture 750–1050, ed. Willem Lourdaux (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1983), 1–49; Semmler, “Benediktinische Reform und kaiserliches Privileg. Zur Frage des institutionellen Zusammenschlusses der Klöster um Benedikt von Aniane,” in Institutionen und Geschichte, ed. Gert Melville (Cologne: Böhlau, 1992), 259–93. For corrections of past research and for further starting points, see Kettemann, “Subsidia Anianensia,” 1–32.

42 Reinhold Rau, ed., “Anonymi vita Hludowici,” in Quellen zur karolingischen Reichsgeschichte 1 (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1977), 1:302–3.

43 Dieter Geuenich, “Gebetsgedenken und anianische Reform. Beobachtungen zu den Verbrüderungsbeziehungen der Äbte im Reich Ludwigs des Frommen,” in Klöster und Bischof in Lotharingien, ed. Raymund Kottje and Helmut Maurer (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1989), 79–106.

44 Martin Allen Claussen, The Reform of the Frankish Church (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

45 Albert Werminghoff, “Die Beschlüsse des Aachener Concils im Jahre 816,” in Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche Geschichtskunde 27 (1902): 605–75.

46 Franz J. Felten, “Auf dem Weg zu Kanonissen und Kanonissenstift. Ordnungskonzepte der weiblichen vita religiosa bis ins 9. Jahrhundert,” in Vita religiosa sanctimonialium, ed. Christine Kleinjung (Korb: Didymos, 2011), 71–92. On the following, see Felten, “Wie adelig waren Kanonissenstifte (und andere weibliche Konvente) im (frühen und hohen) Mittelalter?” in Vita religiosa sanctimonialium, 93–162, here 128–32.

47 Jan Gerchow and Thomas Schilp, eds., Essen und die sächsischen Frauenstifte im Frühmittelalter (Essen: Klartext-Verlag, 2004).

48 See chap. 1, p. 10.

49 Semmler, “Benediktinische Reform,” 274.

50 For an overview, see Prinz, Frühes Mönchtum, 185–262.

51 Berthold Jäger, “Zur wirtschaftlichen und rechtlichen Entwicklung des Klosters Fulda in seiner Frühzeit,” in Hrabanus Maurus in Fulda, ed. Marc-Aeilko Aris and Susana Bullido del Barrio (Freiburg im Breisgau: Knecht, 2010), 81–120.

52 Cosimo Damiano Fonseca, “Farfa abbazia imperiale,” in Farfa abbazia imperiale (Negarine di S. Pietro in Cariano: Il Segno dei Gabrielli Ed., 2006), 1–17.

53 Konrad Hecht, Der St. Galler Klosterplan (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1983). See p. 46 and the website http://www.stgallplan.org/en/index_plan.html.

54 Josef Semmler, “Traditio und Königsschutz,” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung 45 (1959): 1–34.

55 For an overview, see Carlrichard Brühl, Fodrum, gistum, servitium regis (Cologne: Böhlau, 1968).

56 “Notitia de servitio monasteriorum,” ed. Petrus Becker, in Initia consuetudinis Benedictinae, ed. Hallinger, 483–99.

57 Arnold Angenendt, Das Frühmittelalter (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001), 403–6, here 403, 405.

58 For brief treatments in English see the articles “Advocatus/Avoué,” in Medieval France: An Encyclopedia, ed. William W. Kible, et al. (New York: Routledge, 1995), 9; and “Advocate,” in Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, ed. André Vauchez (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000), 1:20. See also Hans-Joachim Schmidt, “Vogt, Vogtei,” in Lexikon des Mittelalters (Munich and Zurich: Artemis & Winkler, 1997), 8:1811–14.

59 Hartmut Hoffmann, Gottesfriede und Treuga Dei (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1964), 11–14.

60 Elmar Hochholzer, “Die lothringische (Gorzer) Reform,” in Die Reformverbände und Kongregationen der Benediktiner im deutschen Sprachraum, ed. Ulrich Faust and Franz Quarthal (St. Ottilien: EOS, 1999), 45–87, here 45–46.

61 Franz J. Felten, Äbte und Laienäbte im Frankenreich (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1980).

62 Johannes Dominicus Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova Amplissima Collectio, vol. 18.1 (Venice, 1773), 271; Felten, Äbte und Laienäbte, 9, 303.