CHAPTER 16

Orbital Fractures

Eric Nordstrom,1 Michael R. Markiewicz,2 and R. Bryan Bell3

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oregon Health and Science University; and Head and Neck Surgical Associates, Portland, Oregon, USA; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Anchorage Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Anchorage, Alaska, USA

2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

3Providence Cancer Center; Trauma Service/Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Service, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center; Oregon Health and Science University; and Head and Neck Surgical Associates, Portland, Oregon, USA

Reconstruction of traumatic orbital defects and restoration of pre-traumatic orbital volume.

Indications for Reduction of Orbital Fractures

- Entrapment demonstrated with a positive forced duction test

- Significant increase in orbital volume

- Dystopia (vertical or horizontal)

- Enophthalmos

- Binocular diplopia that lasts longer than 10–14 days

- Foreign body

- Hard and/or soft tissue loss: orbital floor defect of greater than 1 cm or greater than half of the orbital floor surface area

Contraindications

- Medically unstable

- Edema significant enough to limit clinical exam (relative contraindication)

- Globe rupture or hyphema, or other forms of ocular trauma

- Active infection

Anatomy

- Bones composing the orbit (7): Maxilla, palatine, sphenoid (greater and lesser), zygomatic, frontal, ethmoidal, and lacrimal. The superior orbital fissure separates the greater and the lesser wings of the sphenoid bone

- Contents of the superior orbital fissure: CN III, IV, V1 (nasociliary, frontal and lacrimal branches of the ophthalmic nerve), and VI; sympathetic fibers from the cavernous plexus and the inferior and superior ophthalmic veins

- Contents of the inferior orbital fissure: CN V2 (maxillary nerve), zygomatic nerve, infraorbital nerve, parasympathetic fibers from the pterygopalatine (Meckel's) ganglion, the infraorbital vessels and emissary veins connecting the inferior ophthalmic vein to the pterygoid venous pl

- Contents of optic canal: Optic nerve, meninges, sympathetic fibers, and the ophthalmic artery.

Important orbital wall landmarks

- The optic nerve is located 42 mm, on average, from an intact adult infraorbital (inferior orbital) rim

- The anterior ethmoidal foramen-artery is located 24 mm posterior to the infraorbital rim and anterior lacrimal crest

- The posterior ethmoidal foramen-artery is located 36 mm posterior to the infraorbital rim and anterior lacrimal crest

Transconjunctival (Retro-Septal) Approach

- The patient is placed under general anesthesia with either oral or nasal intubation depending on the nature of the associated facial fractures and the need for maxillomandibular fixation (MMF).

- The patient is positioned within a Mayfield headrest to allow for manipulation of the head during the procedure.

- The patient is prepped with ophthalmic betadine solution (betadine scrub is not recommended for mucous membranes application) and draped. Lacrilube and corneal shields are placed.

- Local anesthesia containing a vasoconstrictor is injected at the sites of the proposed incisions. A higher concentration of local anesthetic should be utilized to decrease the volume injected and minimize distortion of the soft tissue architecture.

- The lower lid is retracted anteriorly with a Desmarres lid retractor (see Figure 16.9 in Case Report 16.1). A malleable retractor is used in conjunction with the corneal shield to retract the globe posterosuperiorly. Care is taken to avoid excessive globe pressure. Additionally, the anesthesiologist should be informed that there will be pressure on the globe to alert him or her of the possibility of decreased pulse rate (oculocardiac reflex).

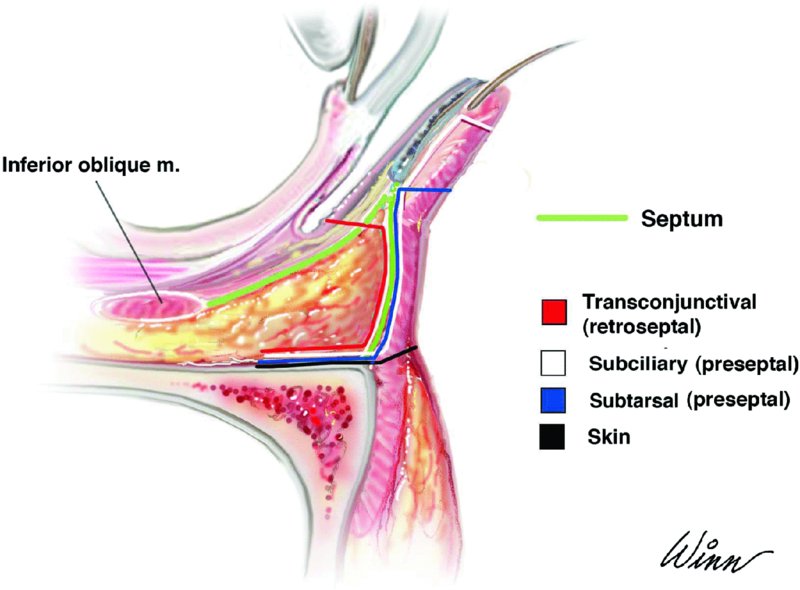

- The transconjunctival incision is initiated lateral to the medial puncta and 5 mm anterior to the scleral- conjunctival interface with a protected needle tip or Colorado tip bovie. The incision transects mucosa directly overlying the infraorbital rim. Once the mucosa is transected, the postseptal approach (Figure 16.1) results in herniation of peri-orbital fat within the incision site. Herniated fat is retracted posteriorly with an orbital or malleable retractor. Dissection proceeds toward the periosteum overlying the infraorbital rim. The periosteum is transected and reflected to expose the infraorbital rim/floor of the orbit. Care is taken to not transect the inferior oblique muscle as it passes between the nasal (medial) and central fad pads.

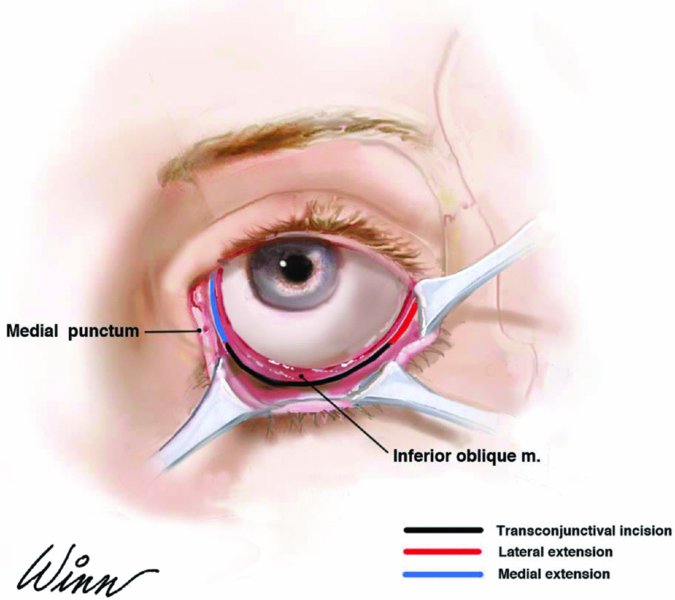

- All displaced fractures (rim and floor) are exposed. Subperiosteal dissection is performed anterior to the transconjunctival incision to expose the infraorbital rim (Figure 16.10, Case Report 16.1) and posteriorly to expose any defects within the orbital floor. The transconjunctival incision may be extended laterally (Figure 16.2) to the zygomaticofrontal suture if additional exposure of the lateral orbital rim is necessary. A lateral canthotomy may be employed if sufficient exposure of the lateral rim cannot be achieved without stretching the lateral orbital tissues excessively.

- If additional exposure of the medial orbital wall is necessary, the transconjunctival incision may be extended medially (Figure 16.2), posterior to the caruncle (transcaruncular incision), and extended along the medial orbital wall. The transcaruncular incision is placed along the conjunctival groove just posterior to the lacrimal sac and semilunar fold. The incision can be extended along the medial orbital rim for approximately 12 mm. A subperiosteal tissue dissection is utilized to expose the medial orbital rim and orbital wall.

- All orbital rim fractures should be exposed to include adjacent uninvolved bone for adequate fixation. All orbital floor fractures should ideally have an area of intact bone circumferentially surrounding the defect.

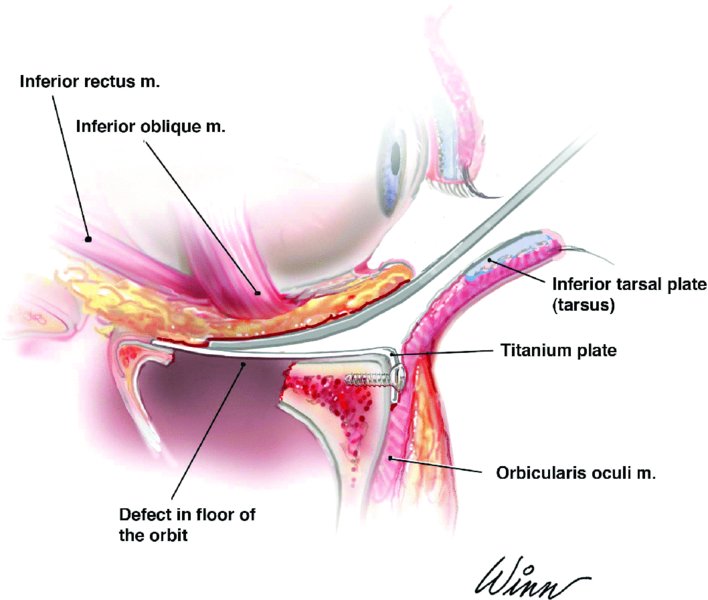

- All areas of tissue entrapment are carefully freed from the orbital floor defect with a blunt-tipped elevator (Cottle or freer elevator) prior to the placement of any orbital fixation devices (Figure 16.3).

- Orbital fixation devices include orbital rim plates, stock titanium orbital meshes, stock preformed titanium orbital reconstruction plates, and custom, prefabricated implants. Orbital rims are typically fixated prior to orbital floors. Orbital rim plates are adapted to the orbital rim and fixated to the uninvolved adjacent orbital rim bone once reduction is obtained. Orbital floor devices are placed, ensuring that all edges of the orbital floor device are positioned on solid bone and with no entrapment of orbital tissues beneath the device (Figure 16.3; see also Figure 16.11, Case Report 16.1). The posterior ledge of an orbital floor device requires a minimum of a 2–3 mm purchase. The orbital floor device is evaluated for adequate antral bulge reconstruction, orbital volume restoration, and intact bone along the periphery of the device prior to fixation.

- The orbital floor device can be fixated with self-drilling 4 mm screws along the infraorbital rim (provided the rim is intact). If an orbital floor device cannot be placed without entrapment of tissues, a molded piece of smooth alloplastic material can be utilized if the defect is not excessively large to accept the material without distortion. Once materials have been fixated, the orbital soft tissue around the margins of the device are reevaluated to ensure no tissue entrapment, and a final forced duction test is performed.

- Once anatomic reduction has been verified, additional fixation screws are placed. Complete closure of the transconjunctival incision is not recommended as excessive suturing can contribute to shortening of conjunctival tissues. For large incisions, 2-4, 6-0 plain gut sutures may be placed in an interrupted fashion to loosely reapproximate the conjunctiva.

Figure 16.1. Approaches to the infraorbital (inferior orbital) rim and floor. Note that the subciliary and the subtarsal approaches access the rim by creating a stair-step incision through the orbicularis oculi muscle at any point along the dissection.

Figure 16.2. Locations of the transconjunctival incision with medial and lateral extensions.

Figure 16.3. Transconjunctival approach depicting appropriate reconstruction of an orbital floor defect with elevation of herniated contents from the maxillary sinus and the posterior aspect of the orbital floor device resting on solid bone.

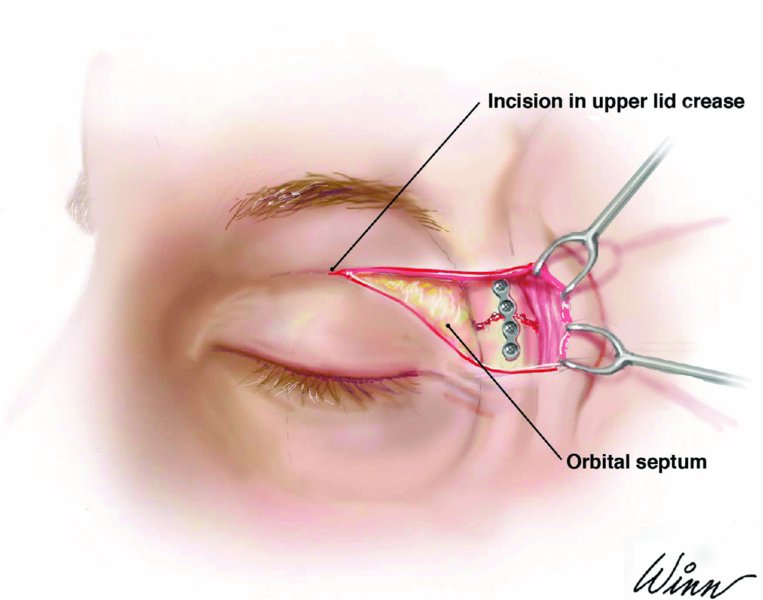

Figure 16.4. While retracting the skin-muscle flap superiorly with a double-ended skin hook, the periosteum is incised and the orbital rim fractures are exposed, reduced, and fixated.

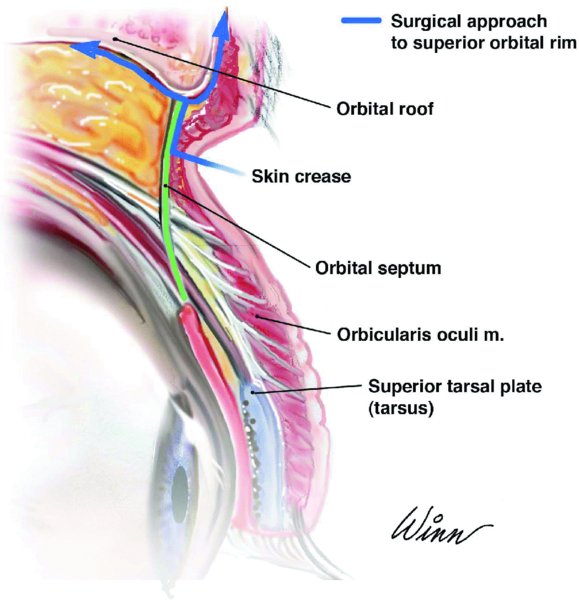

Figure 16.5. A superior blepharoplasty approach is initiated with a skin incision made parallel to the superior palpebral sulcus within a naturally occurring skin crease. The dissection remains superficial to the orbital septum.

Figure 16.6. Infraorbital (mid-lid) or subtarsal incisions allow for wide surgical exposure of the infraorbital rim and floor without the need for a lateral canthotomy when repairing complex orbital fractures and/or in cases of significant periorbital edema.

Figure 16.7. Grossly comminuted or displaced fractures of the supraorbital roof, combined neurosurgical intervention or orbital fractures combined with additional facial fractures are best managed with wide surgical access via a coronal approach with or without additional approaches.

Figure 16.8. Coronal computed tomography scan demonstrating a right orbital floor fracture, a significant change in right orbital volume, and fluid within the bilateral maxillary sinuses.

Figure 16.9. A malleable retractor is used to retract the globe posterosuperiorly, and a Desmarres lid retractor is utilized to retract the lower lid anteroinferiorly in preparation for a retroseptal transconjunctival incision.

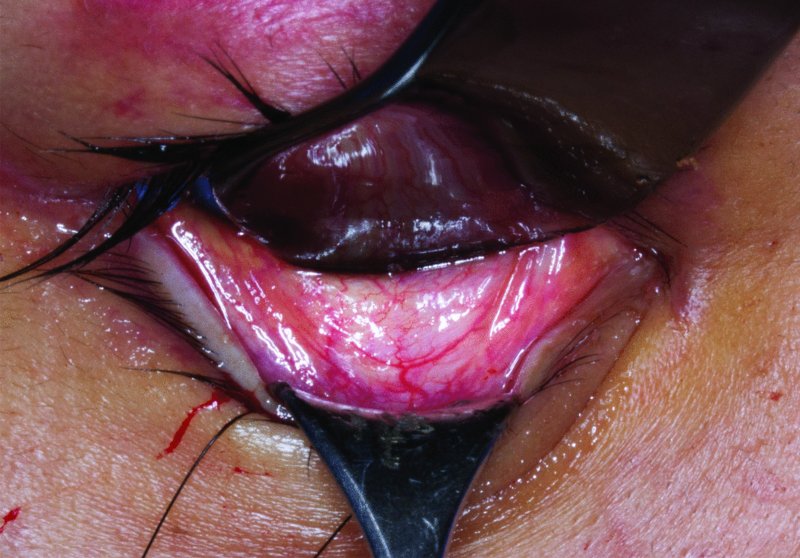

Figure 16.10. The orbital rim and orbital floor are exposed.

Figure 16.11. A titanium mesh is bent to reestablish pre-traumatic orbital volume, to elevate herniated tissue from the sinus, and to bridge any continuity defects located within the fractured orbital floor.

Figure 16.12. Postoperative coronal computed tomography scan demonstrating appropriate reconstruction of the orbital floor defect and reestablishment of pre-traumatic orbital volume.

Upper Eyelid (Superior Blepharoplasty, Supratarsal Fold) Incision Approach

- Steps 1–4 of the above transconjunctival approach are followed.

- An incision is made parallel to the superior palpebral sulcus within a naturally occurring skin crease (Figure 16.4) or, if edema is present, 10 mm above the upper eyelid. The involved upper eyelid may be compared to the contralateral side to ensure appropriate incision placement. The incision may be extended laterally into the crow's feet area for additional exposure, staying 6 mm superior to the lateral canthus to avoid the frontal branch of the facial nerve.

- The incision transverses skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the orbicularis oculi. A skin-muscle flap is developed, staying superficial to the orbital septum–levator aponeurosis (Figure 16.5). The dissection is directed superiorly and laterally toward the zygomaticofrontal suture or supraorbital rim. While retracting the skin-muscle flap superiorly with a double-ended skin hook, a periosteal incision is made over the rim (Figure 16.4). The trochlea and superior oblique muscle may be dissected from the trochlear fossa for added exposure of the orbital rim. Fractures are exposed, reduced, and fixated with orbital rim plates (Figure 16.4) and/or mesh.

- After appropriate supraorbital rim reconstruction and orbital volume restoration, closure of the upper eyelid incision is performed in a layered fashion with 4-0 Vicryl sutures to close the periosteum and running 6-0 fast-absorbing gut sutures to close skin. Avoid excessive bites of skin as this can contribute to shortening of the upper lid and increase scleral show.

Postoperative Management

- Immediate postoperative visual acuity and extraocular muscle movement tests are performed. Evaluation is ideally performed within the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) so that deficits amenable to surgical intervention may be performed as soon as possible. Basic salt solution (BSS) irrigant should be used if there is suspicion that eye lubricants could be interfering with visual exams. Except in the setting of true entrapment with significant inflammation, extraocular movement should not cause pain postoperatively.

- Patients are typically admitted for 23-hour observation following extensive orbital surgery.

- If intraoperative computed tomography (CT) scanning is not readily available, a postoperative CT scan should be performed to evaluate the position of the orbital fixation device and to identify any areas of potential entrapment.

- A course of steroids and antibiotics in the perioperative period is recommended.

- Head-of-bed elevation is recommended during the immediate postoperative period.

- Ice is applied to the affected periorbital region for the first 48 hours.

- Sinus precautions are used preoperatively and for 2 weeks after orbital repair.

- Oxymetazoline nasal spray is recommended for symptomatic relief in the immediate postoperative period for 2–3 days only.

- Pseudoephedrine hydrochloride is recommended for symptomatic relief in the immediate postoperative period and is scheduled for 5 days.

- Lacrilube may be used in the setting of severe chemosis.

- Ophthalmic eye drops are not routinely prescribed, but they may be used for lagopthalmos with transconjunctival incisions for 5–7 days.

Complications

Early Complications

- Optic neuropathy resulting in partial or complete vision loss

- Entrapment of the extraocular muscles, esotropia, or disorders of ocular motility

- Corneal abrasion or other globe injury

Late Complications

- Volume-associated changes resulting from inadequate reduction of orbital contents: enophthalmos, lateral or vertical dystopia, or hypoglobus

- Ectropion or entropion with or without lower lid retraction and increased scleral show

Key Points

- Pre-septal approaches are prone to ectropion, which is particularly true when combined with a lateral canthotomy. When performing lateral canthotomies, care should be taken to resuspend the periorbital musculature and to perform an accurate lateral canthopexy upon closure. When wide access is required to expose the infraorbital rim, particularly in a posttraumatic patient where edema persists, an infraorbital (mid-lid) incision (Figure 16.6) is a predictable means of obtaining wide surgical exposure of the infraorbital rim and orbital floor without the need for a lateral canthotomy. The infraorbital incision provides acceptable cosmesis, while minimizing the risk of ectropion and increased scleral show.

- In the author's experience, a transconjunctival incision combined with a lateral canthotomy for disarticulation of the lower lid often results in an unnatural appearance of the lateral periorbita. An isolated postseptal transconjunctival approach combined with an upper lid blepharoplasty approach typically provides adequate access to the orbit for most applications and results in better postoperative cosmesis. For grossly comminuted or displaced fractures of the supraorbital rim, combined neurosurgical intervention or orbital fractures combined with additional facial fractures, a coronal approach provides direct access to the upper half of the orbit and supraorbital roof (Figure 16.7).

- The key to successful orbital reconstruction is to reestablish pre-traumatic orbital volume through restoration of the critical orbital bulges located postero-inferiorly (antral bulge) and postero-medially (ethmoidal bulge). The typical error is that the surgeon places the orbital implant flush with the anterior portion of the orbit, and it extends directly back to the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus. A similar error is made along the medial orbital wall by inaccurately positioning the orbital implant into the ethmoidal labyrinth.

- In the author's experience, titanium plates are the most predictable and versatile implant materials due to the rapid bending of the devices to the anatomical contours of orbital floor and medial orbital wall fractures without the need for a second surgical site. For larger fractures, preformed titanium orbital reconstruction plates (Synthes, Paoli PA) allow for rapid and accurate restoration of orbital volume. Care must be taken to avoid “yaw” inaccuracies during device placement, which result in unfavorable positioning of the implant within the posterior-medial orbit with resultant postoperative enophthalmos.

- Once the orbital device is secured, a forced duction should be performed to verify free ocular mobility. Projection, globe position, and eyelid anatomy should also be evaluated prior to extubation.

- Intraoperative CT scanners provide immediate quality control and allow for intraoperative revision of inaccurately positioned orbital devices. A radiolucent and carbon-fiber Mayfield headrest is required, and preoperative consent for the possibility of multiple CT scans is advisable. Modern mobile CT scanners can be linked to navigation systems to provide real-time assistance in accurate implant placement.

- Recently, preoperative computer-assisted planning with virtual correction and construction of stereolithographic models has been combined with intraoperative navigation in an attempt to more accurately reconstruct the bony orbit and optimize treatment outcomes. Surgical procedures are preplanned with virtual correction by mirroring an individually defined 3D segment of the unaffected side into the deformed side, creating an ideal unilateral reconstruction. These computer models are used intraoperatively as a virtual template to navigate the preplanned bony contours and globe projection.

References

- Baumann, A. and Ewers, R., 2000. Transcaruncular approach for reconstruction of medial orbital wall fracture. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 29(4), 264–7.

- Bell, R.B. and Al Bustani, S., 2012. Management of orbital fractures. In: S.C. Bagheri, R.B. Bell and H.A. Kahn, eds. Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier.

- Bell, R.B. and Markiewicz M.R., 2009. Computer assisted planning, stereolithographic modeling and intraoperative navigation for complex orbital reconstruction: a descriptive study on a preliminary cohort. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 67(12), 2559–70.

- Converse, J.M., Firmin, F., Wood-Smith, D. and Friedland, J.A., 1973. The conjunctival approach in orbital fractures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 52(6), 656–7.

- Ducic, Y. and Verret, D.J., 2009. Endoscopic transantral repair of orbital floor fractures. Otolaryngology—Head Neck Surgery, 140(6), 849–54.

- Markiewicz, M.R., Dierks, E.J. and Bell, R.B., 2012. Does intraoperative navigation restore orbital dimensions in traumatic and post-ablative defects? Journal of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery, 40(2), 142–8.

- Markiewicz, M.R., Dierks, E.J., Potter, B.E. and Bell, R.B., 2011. Reliability of intraoperative navigation in restoring normal orbital dimensions. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 69(11), 2833–40.

- Shorr, N., Baylis, H.I., Goldberg, R.A. and Perry, J.D., 2000. Transcaruncular approach to the medial orbit and orbital apex. Ophthalmology, 107(8), 1459–63.

- Tessier, P., 1969. Surgical widening of the orbit. Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthétique, 14(3), 207–14.

- Tessier, P., 1973. The conjunctival approach to the orbital floor and maxilla in congenital malformation and trauma. Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery, 1(1), 3–8.

- Walter, W.L., 1972. Early surgical repair of blowout fracture of the orbital floor by using the transantral approach. Southern Medical Journal, 65(10), 1229–43.