CHAPTER 17

Nasal Fractures

Hani F. Braidy and Vincent B. Ziccardi

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, New Jersey Dental School, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey, USA

Reduction of displaced nasal bones and associated nasal structures.

Indications for Closed Reduction of Nasoseptal Fractures

- Displaced fractures with cosmetic deformity

- Fractures with resulting nasal obstruction

- Severely comminuted fractures

Indications for Open Reduction of Nasoseptal Fractures

- Severely displaced fractures

- Severe displacement of the nasal cartilage complex

- Concomitant extensive lacerations

- Remaining deformity after closed reduction

Contraindications

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea

- Old fractures (>4 weeks)

Anatomy

- The pyramidal-shaped nasal bone complex includes the paired nasal bones that articulate with the nasal processes of the frontal bone and the maxilla.

- The nasal septum consists of the following structures: crest of the maxillary and palatine bone, perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, vomer, and quadrangular cartilage.

- The nose has an extensive blood supply derived from the internal carotid (anterior ethmoidal artery and branches) and external carotid (greater palatine, superior labial, sphenopalatine, and angular arteries) artery.

- Anterior epistaxis typically involves a complex of vessels known as Little's area or Kiesselbach's plexus (the confluence of the anterior ethmoidal, greater palatine, superior labial, and sphenopalatine arteries).

Closed Nasoseptal Reduction Technique

- Depending on the degree of displacement, patients are treated with local, intravenous, or general anesthesia. With general anesthesia, the patient is orally intubated, and the nasal cavities and maxillofacial skeleton are prepped and draped.

- The nasal complex is anesthetized with local anesthetic containing a vasoconstrictor injected along the nasal floor, lateral nasal walls, septum, turbinates, and nasal bridge. Infraorbital, infratrochlear, and supratrochlear bilateral blocks are performed as well.

-

Intranasal packings containing oxymetazolin (or 4% cocaine) are placed within the bilateral nasal cavities (see Figure 17.4 in Case Report 17.1).

- A sterile marking pen is used to mark the location of the medial canthal tendons (MCT) and the midline.

-

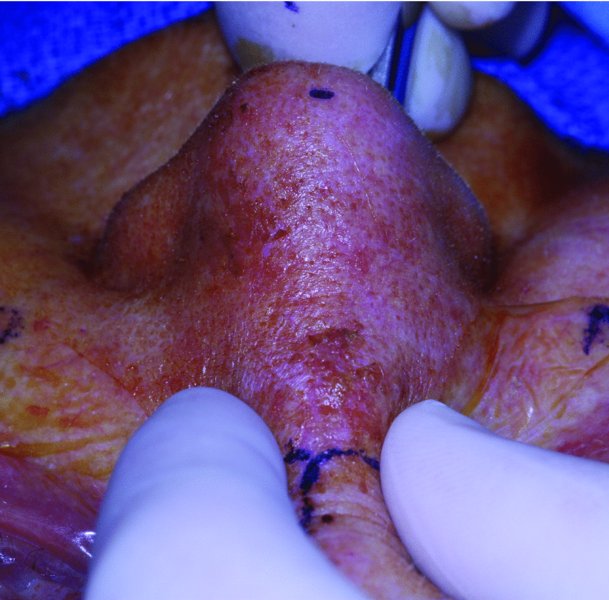

The distance between the nostril and the bridge of the nose (nasofrontal suture) is estimated by placing the Goldman elevator against the external surface of the nose with its tip next to the medial canthus (Figure 17.5, Case Report 17.1). A fingertip from the dominant hand is placed on the instrument to “mark” that distance. The instrument is introduced into the nose and directed superiorly and laterally to reduce the displaced nasal bones, while the fingers of the nondominant hand provide counterpressure externally and aid in molding the nasal bones (Figure 17.1; and see Figure 17.6, Case Report 17.1).

- An Asch forceps is then used to reduce the nasal septum over the maxillary crest (Figure 17.7, Case Report 17.1). If the nasal septum cannot be reduced with the Asch forceps alone, a septoplasty can be performed with a Killian or hemi-transfixion incision with mucoperichondrial flap elevation.

-

The nose is reexamined with a nasal speculum to view the position of the septum and to evaluate the nasal passages for obstruction and septal hematoma formation. Doyle splints are placed if septal hematoma evacuation has been performed or if tears are present within the nasal mucosa to minimize synechiae formation (Figure 17.9, Case Report 17.1). Doyle splits are impregnated with triple antibiotic ointment, placed within the nasal passages, and secured to the membranous septum with a 3-0 silk suture (Figure 17.10, Case Report 17.1).

-

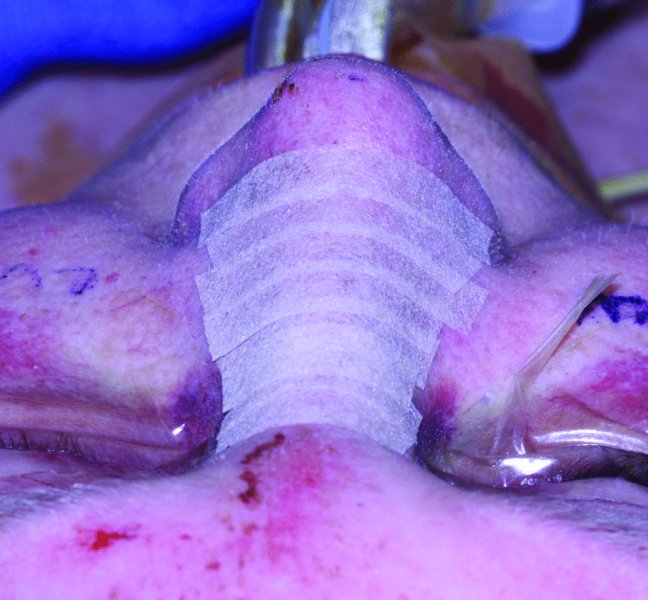

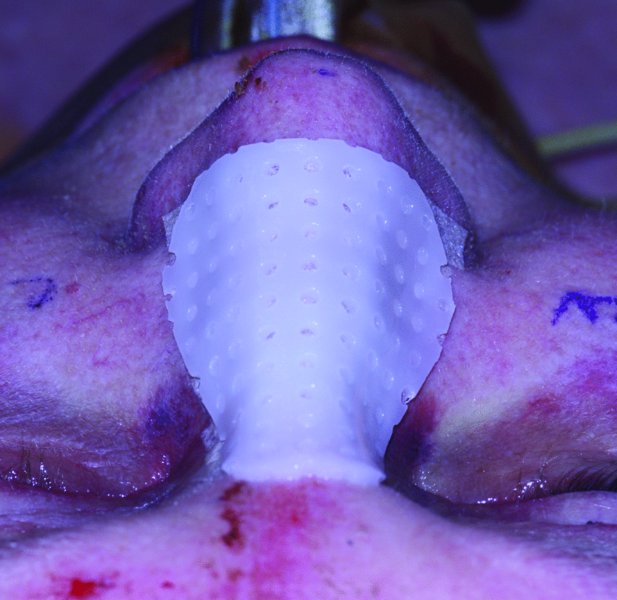

Steri-strips are placed over the nasal bridge (Figure 17.11, Case Report 17.1), and an Aquaplast thermoplastic nasal splint is heated, trimmed, and applied to the nasal dorsum (Figure 17.12, Case Report 17.1).

Figure 17.1. The nasal fracture is reduced with a lateral and superior rotation of the reduction forcep.

Figure 17.2. Epistat nasal catheter capable of placing anterior, posterior, or combined nasal pressure to arrest epistaxis.

Figure 17.3. Gross nasal and septal deformity.

Figure 17.4. Oxymetazolin pads placed within the nasal cavities for hemostasis.

Figure 17.5. Marks are placed at the midline and the medial canthal tendons (MCT). The distance from the nostril to the MCT is estimated with a Goldman elevator.

Figure 17.6. A Goldman elevator is used to reduce the displaced nasal fractures. The nondominant hand is used to apply counterpressure and to mold the fractured nasal bones.

Figure 17.7. Asch forceps used to reduce the septal fracture and position the septum midline.

Figure 17.8. Postreduction view. Nasal tip, septum, and nasal bones are midline.

Figure 17.9. Doyle splints impregnated with antibiotic ointment are placed.

Figure 17.10. Doyle splints are secured to the membranous septum with silk sutures.

Figure 17.11. Steri-strips are placed over the nasal dorsum.

Figure 17.12. Aquaplast thermogenic splint in place.

Open Nasoseptal Reduction Technique

- General anesthesia is utilized. Patient prepping, draping, local anesthetic placement, and intranasal packings are placed in a similar fashion to the closed nasoseptal reduction technique.

-

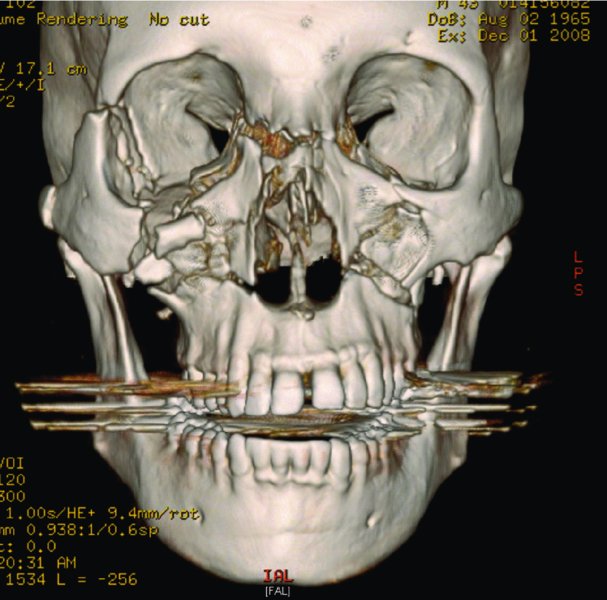

Open exposure of the nasal complex is performed using any combination of skin lacerations, lynch incisions, open-sky (“H”) incisions (Figures 17.14 and 17.16, Case Report 17.2), open rhinoplasty, and septoplasty incisions.

- Conservative exposure of the cartilage and bony fragments is recommended to minimize the risk of devitalization. Care is taken to not strip the media canthal tendons from their insertions.

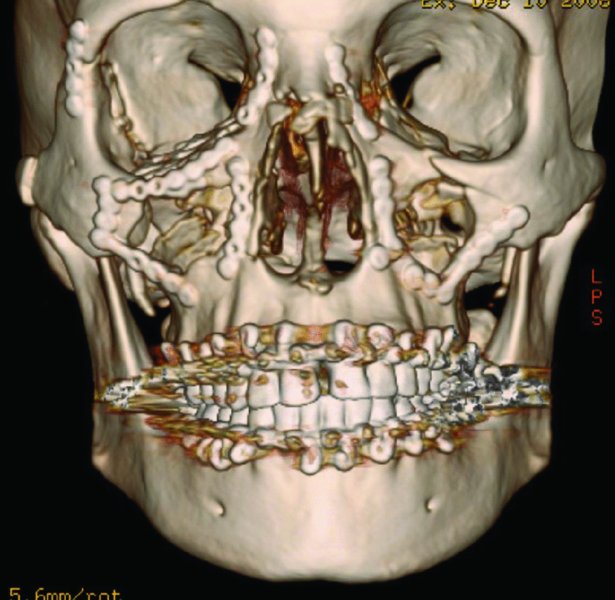

- Mini-plates and screws are used to stabilize the displaced fragments (Figure 17.14, Case Report 17.2). In avulsive injuries or when extreme comminution is present, a split calvarial bone graft or other autogenous or alloplastic implant may be required to reconstruct the nasal bridge.

- Cartilage is sutured in place with slow resorbing sutures. Doyle splints will provide additional support for comminuted segments.

- Skin and intranasal incisions are closed with resorbable sutures.

- If nasal dorsal sutures are placed, Aquaplast thermoplastic nasal splints are typically not placed as they will interfere with wound care.

Figure 17.13. 3D reconstruction demonstrating comminuted midface and nasal fractures.

Figure 17.14. Open-sky (“H”) incision is utilized to gain access to the comminuted nasal fractures.

Figure 17.15. Postoperative 3D reconstruction demonstrating reduction of comminuted nasal fractures and associated facial fractures.

Figure 17.16. 10 weeks postoperative appearance of the open-sky (“H”) approach.

Postoperative Management

- The patient is instructed to apply ice to the face and keep the head elevated for 48 hours.

- The patient is instructed to avoid nose blowing, sneezing, and strenuous activity to avoid rebleeding or fracture displacement.

- Analgesics, decongestants, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed.

- Intranasal packing (iodoform gauze) is removed 3–5 days postoperatively to prevent toxic shock syndrome and sinusitis. If additional internal support is required, a new intranasal packing can be placed. Doyle splints can be left in place for several weeks. External nasal splints are removed 7–10 days postoperatively.

Complications

Early Complications

- Epistaxis: Minor bleeding may be controlled by elevation of the head and external pressure. More persistent nasal bleeding may require placing an intranasal pack.

- Septal hematoma: Immediate drainage of the hematoma and placement of an intranasal pressure packing is paramount to prevent cartilage necrosis, septal perforations, and saddle nose deformity.

- Nasolacrimal duct injury: A consultation with an ophthalmologist is necessary if epiphora does not improve within a few weeks after resolution of edema.

- CSF rhinorrhea: Typically present with fractures of the cribriform plate. Diagnosed with B2 transferrin (preferred method), ring test, or CSF glucose analysis.

Late Complications

- Nasal deformity, septal deformity, or saddle nose deformity: Secondary rhinoplasty may be needed to address this late complication.

- Nasal obstruction: Typically results from a deviated septum, this complication can be addressed by secondary septorhinoplasty.

- Septal perforation: Typically results from unrecognized septal hematoma. Treatment involves local flap advancements.

- Synechiae: Synechiae result from damage to the nasal mucosa resulting in scar tissue formation, commonly between the turbinate and the septum. Synechiae formation results in nasal obstruction. Treatment requires secondary release.

Key Points

- Thorough clinical and radiographic examinations are performed in order to evaluate for cribriform plate fractures, septal hematoma, and CSF rhinorrhea.

- If extensive facial edema is present, reduction is delayed 5–7 days until the majority of the edema has resolved.

- Most causes of nasal epistaxis are effectively treated with an anterior nasal pack. One-fourth-inch Vaseline iodoform gauze is packed in a layered fashion starting at the nasal floor. Alternatively, commercially prepared nasal packs such as a Merocel pack (Medtronic, Jacksonville, FL, USA) or a Rapid Rhino (ArthroCare ENT, Austin, TX, USA) act as nasal tampons to stop anterior nasal bleeds. In the event that hemostasis is not achieved with the placement of an anterior nasal pack, a posterior nasal bleed is suspected. A pediatric Foley catheter is lubricated with an antibiotic ointment, introduced into the nostril, and inserted posteriorly until its tip can be visualized in the posterior pharynx. The balloon is inflated with 7–10 cc of normal saline and pulled against the nasopharynx, and tightly secured by clamping a hemostat adjacent to the nostril. To prevent alar necrosis, the nostril is padded with gauze. The anterior nasal cavity is then packed with iodoform gauze or other commercial nasal packs. Alternatively, an Epistat nasal catheter (Medtronic) (Figure 17.2) can be introduced into the nasal passage, and pressure may be applied to an anterior bleed, posterior bleed, or both. For persistent epistaxis that is refractory to treatment, interventional radiology may be required to embolize the offending vessel.

References

- Bartkiw, T.P., Pynn, B.R. and Brown, D.H., 1995. Diagnosis and management of nasal fractures. International Journal of Trauma Nursing, 1(1), 11–18.

- Fattahi, T., Steinberg, B., Fernandes, R., Mohan, M. and Reitter, E., 2006. Repair of nasal complex fractures and the need for secondary septo-rhinoplasty. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 64(12), 1785–9.

- Indresano, T., 2005. Nasal fractures. In: R. Fonseca, ed. Oral and maxillofacial trauma. Vol. 2. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. Pp. 737–50.

- Kucik, C.J. and Clenney, T., 2005. Management of epistaxis. American Family Physician, 71(2), 305–11.

- Mondin, V., Rinaldo, A. and Ferlito, A., 2005. Management of nasal bone fractures. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 26(3), 181–5.

- Powers, M.P., 2005. Management of soft tissue injuries. In: R. Fonseca, ed. Oral and maxillofacial trauma. Vol. 2. 3rd ed. St. Louis MO: Elsevier Saunders. Pp. 791–800.

- Ziccardi, V.B. and Braidy, H., 2009. Management of nasal fractures. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 221(2), 203–8, vi.