CHAPTER 33

Autogenous Reconstruction of the Temporomandibular Joint

John N. Kent1 and Christopher J. Haggerty2

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

2Private Practice, Lakewood Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Specialists, Lees Summit; and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri, USA

A means of reconstructing acquired and congenital temporomandibular joint (TMJ) abnormalities.

Indications

- Reconstruction of defects resulting from acquired joint abnormalities (primary fibrous and bony ankylosis, infection, osteoarthritis, idiopathic condylar resorption, rheumatic diseases, neoplasms, and posttraumatic deformities)

- Reconstruction of defects resulting from congenital joint abnormalities caused by malformations of the structures of the first and second branchial arches (hemi-facial microsomia, Goldenhar syndrome [oculo-auriculo-vertebral syndrome], otomandibular dysostosis, and lateral facial dysplasia)

- Failure of components of alloplastic joint prosthesis, if scar bed is not excessive

- When reconstruction with an alloplastic prosthesis is cost-prohibitive

- Severe occlusal discrepancies involving the TMJ and associated structures that are not amendable to conventional orthognathic surgery

Contraindications

- Children without the complete eruption of the primary dentition

- Multiple operated joints

- Active infection

- Psychiatric disorders

- Medically compromised individuals: the very elderly, those with uncontrolled systemic diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unstable cardiovascular issues, and poorly controlled diabetes), and those with drug and/or alcohol addiction

- Patients unable or unwilling to perform recommended postoperative physical therapy and cooperate with rehabilitation protocols

Autogenous TMJ Replacement Procedure: Costochondral Graft

- Intravenous antibiotics, steroids, and antisialogues are given preoperatively. The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table and nasally intubated. Short-acting paralytics are used in order to test for branches of the facial nerve during the procedure. Separate intraoral and facial–chest instrument tray setups are created. Protective draping and/or redraping and prepping are always recommended throughout the procedure to avoid cross-contamination between the mouth and face–chest when going back and forth between sterile and nonsterile (oral) environments.

- A throat pack is placed within the posterior oropharynx. If orthodontic appliances are not in place, mandibular and maxillary Erich arch bars are placed, but maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is not initiated.

- The patient is prepped in a sterile fashion. The oral cavity is prepped with Betadine paint (Betadine scrub is not recommended for mucous membranes application), and a sterile gauze is placed between the dentition and the internal surface of the lips to prevent the contamination of the extraoral field with saliva. The external auditory canals are prepped with Betadine paint, and an antibiotic impregnated ear wick is placed within the external auditory canals bilaterally. The remainder of the facial skeleton is prepped with Betadine paint from the scalp to the clavicles. The patient is draped to allow for exposure of bilateral pre-auricular and retromandibular incisions (even if only anticipating ipsilateral surgery) and the oral cavity.

- The head is turned 45° to the contralateral side. The affected joint is approached via a combined pre-auricular and modified-retromandibular approach (refer to Chapter 32). A nerve stimulator is used to test for branches of the facial nerve.

- A gap arthroplasty is performed from the glenoid fossa to the sigmoid notch. Diseased or deformed bone, scar tissue, and/or the involved condyle is removed, leaving a gap of approximately 15–20 mm from the ascending ramus osteotomy to the glenoid fossa. An ipsilateral coronoidectomy is performed. On occasion, if the patient has appreciable lateral pterygoid muscle function, the anterior aspect of the mandibular condyle with lateral pterygoid muscle attachment can be placed beneath the sigmoid notch area with a bone screw to preserve a portion of the lateral pterygoid function.

-

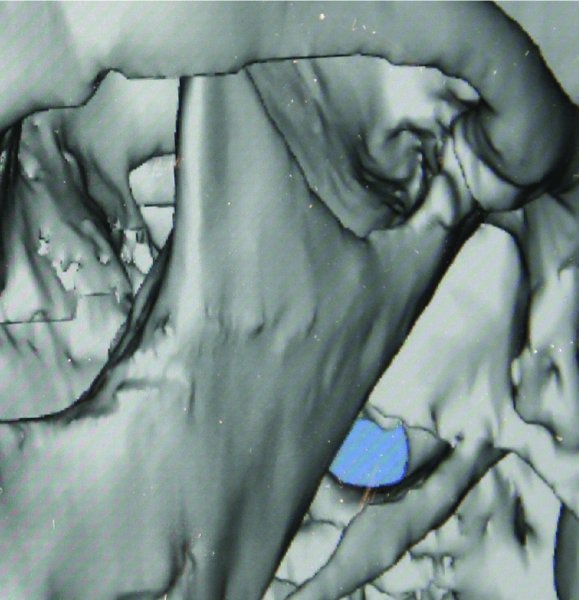

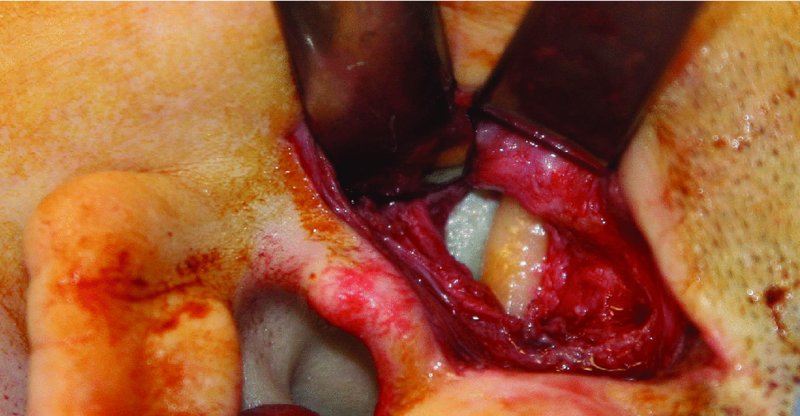

The glenoid fossa is smoothed or reshaped (Figure 33.6 [all figures cited in this list appear in Case Report 33.1]), and, if present, the native disc is preserved.

- After completion of the gap arthroplasty, the oral cavity is entered and mandibular movement is assessed to confirm unrestricted function. If mandibular movement is less than 35 mm, the gap arthroplasty site is inspected for interferences. Areas of scar tissue are removed from the ascending ramus, lateral and medial surfaces, and inferior border of the mandible. If interferences are identified on the contralateral side, a contralateral coronoidectomy should be performed. If contralateral interferences are present after coronoidectomy, contralateral open arthroplasty should be considered.

- After obtaining and confirming adequate mandibular movement, the patient is placed into MMF, the oral gauze located between the dentition and the internal surfaces of the lips is replaced, the patient is reprepped and draped extraorally with betadine paint, and the surgeon's gloves are changed to prevent contamination of the extraoral surgical sites with oral microbes.

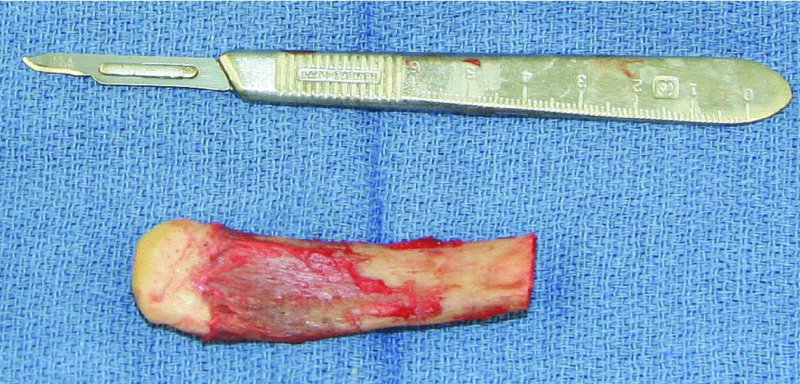

- The autogenous graft is harvested after the gap arthroplasty is completed and all interferences are addressed (Figure 33.7).

-

For costochondral grafts (CCGs), the cartilage head is reshaped to mimic a condylar head and to seat ideally within the glenoid fossa (Figure 33.8). Five to ten millimeters of cartilage are preserved at the rib– cartilage junction. The CCG should fit passively along the lateral surface of the ascending ramus while the CCG's cartilaginous cap is seated within the glenoid fossa (Figure 33.10).

- In order to maximize CCG contact with the lateral ascending ramus, autogenous interpositional grafting may need to be performed between the CCG and the lateral ascending ramus as the rib may be slightly curved as it opposes the flat ramus surface. It is prudent to harvest 1–2 cm of rib beyond the intended graft length. Sources of potential autogenous bone include the distal aspect of the rib harvested and/or adjacent ribs.

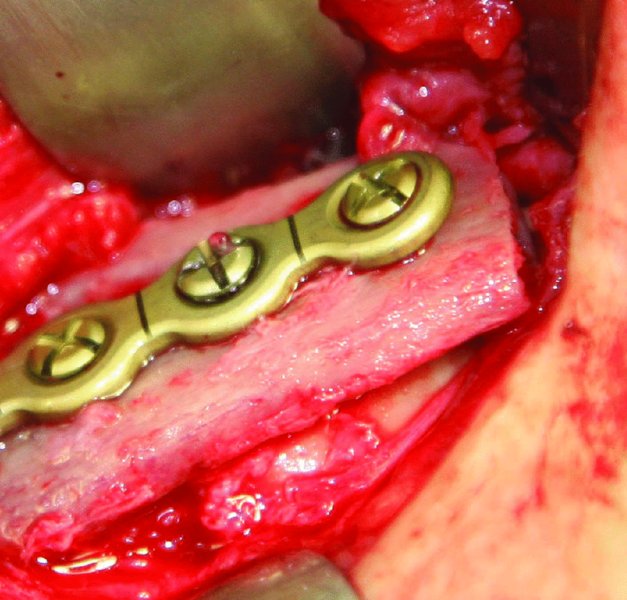

- The CCG is secured to the lateral ascending ramus with rigid fixation in the form of plate fixation using 3–4 screws (Figure 33.9).

- After fixation of the CCG, the face is draped out, and the oral cavity is entered. MMF is removed, and mandibular movement and occlusion are confirmed prior to closing the extraoral incisions in a layered fashion. Drains are typically not necessary. The patient is placed into light guiding elastics, and a pressure dressing is applied to the facial skeleton.

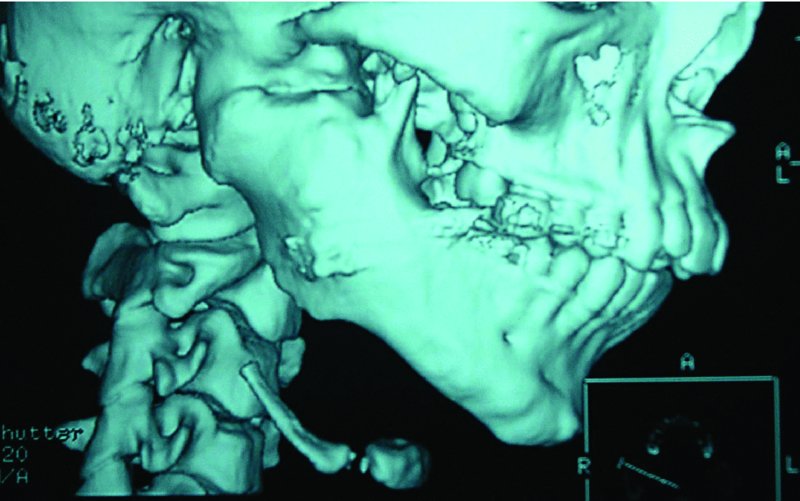

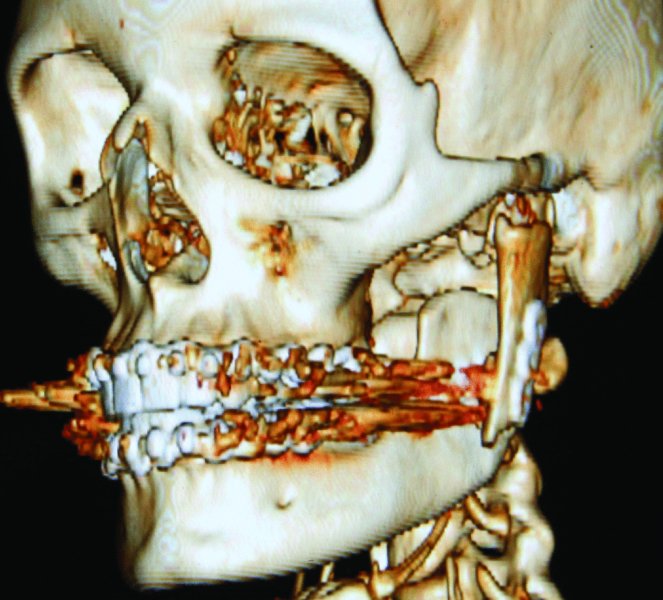

Figure 33.1. 3D reconstruction demonstrating a complete right-sided temporomandibular joint bony ankylosis.

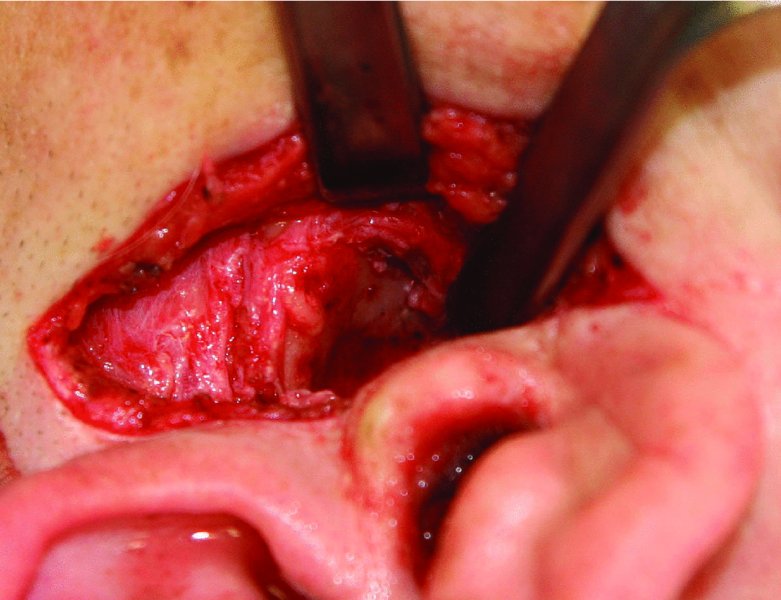

Figure 33.2. Intraoperative image of the patient in Figure 33.1 with complete bony ankylosis of the right temporomandibular joint space.

Figure 33.3. Larger ankylotic masses are sectioned and removed in smaller pieces.

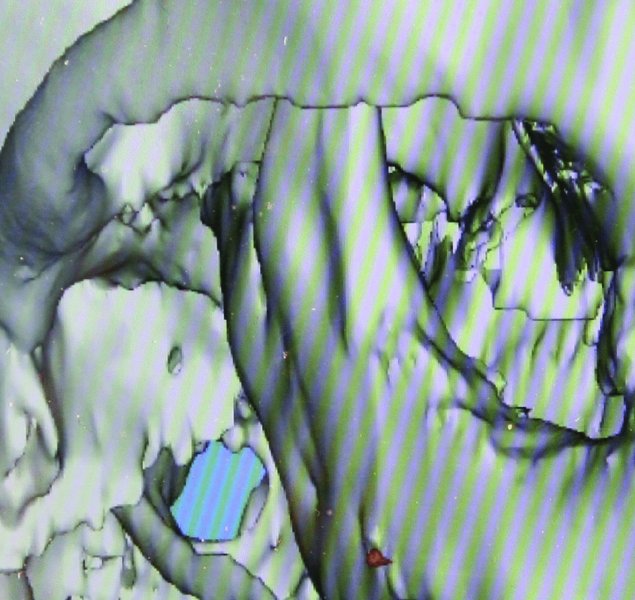

Figure 33.4. 3D reconstruction views demonstrating bilateral condylar degeneration secondary to rheumatoid disease.

Figure 33.5. The preauricular and modified-retromandibular approaches allow access to the mandibular condyle, coronoid process and ascending ramus.

Figure 33.6. The degenerative condyle and coronoid process have been excised, establishing a 15–20 mm gap between the ascending ramus and the glenoid fossa. The glenoid fossa has been reshaped and all interferences have been removed.

Figure 33.7. Bilateral degenerative condyles and coronoid processes. Ribs 5 and 6 prior to reshaping.

Figure 33.8. The costal cartilage is reshaped to function as a condyle and to articulate ideally within the glenoid fossa.

Figure 33.9. The costochondral graft (CCG) is secured to the lateral surface of the ascending ramus with plate fixation. The titanium plate acts as a washer and distributes the compression forces along the lateral surface of the CCG.

Figure 33.10. The cartilaginous cap of the costochondral graft articulates ideally within the glenoid fossa.

Postoperative Management

- Antibiotics are given immediately preoperatively and for 2 weeks postoperatively.

- The patient is functioned immediately after surgery with nonforceful, passive jaw exercises.

- For the first 10–12 weeks, patients are allowed to function with a soft mechanical (nonchew) diet and guiding elastics during the day. At night, patients are placed into MMF via heavy elastics.

- Arch bars or orthodontic appliances are removed at 3 months provided occlusion is satisfactory and the interincisal opening is reaching a 30 mm range. Aggressive physiotherapy is continued for 3–12 months in order to maintain a maximum opening of 30–35 mm and to minimize recurrent ankylosis.

Complications

- Donor site morbidity: Refer to Chapter 35.

- Reankylosis: Minimized with complete removal of the ankylotic mass and appropriate physiotherapy.

- CCG overgrowth and undergrowth: Minimized by leaving 10 mm or less of a cartilaginous cap at the rib–cartilage junction and with postpubertal CCGs.

- Facial nerve damage or paralysis: Minimized with appropriate incision placement, meticulous dissection, and the use of a nerve stimulator.

- Fracture at the costal cartilage–rib interface: Can be minimized by leaving 10 mm or less of cartilage at the rib–cartilage junction and avoiding early, excessive loading of the CCG.

- Fracture or splintering of the rib: Minimized by using plate fixation instead of lag or positional screw fixation.

- Hardware failure or graft mobility: Minimized with the use of screw and plate rigid fixation of the graft to the lateral ascending ramus. A minimum of three screws should be utilized to fixate the CCG to the ascending ramus.

- Infection: Minimized with strict attention to sterile technique and wound closure in a layered fashion. Gowns and gloves should be changed when alternating from the oral cavity to extraoral incisions in order to minimize contamination of the extraoral sites with oral microbes. Separate instruments and instrument tables should be established for oral and extraoral instruments in order to avoid cross-contamination.

- Malocclusion: Minimized with the use of a prefabricated occlusal splint, rigid fixation of the graft material, and the use of heavy elastic MMF at night for 3 months postoperatively.

- Graft resorption: Rare. When graft resorption occurs, it is typically seen in children and young adults.

Key Points

- TMJ reconstruction not only aids in correcting functional disorders (restricted mouth opening, malocclusion, and malnutrition), but also can improve cosmetic disabilities and dentofacial deformities.

- Autogenous sources for TMJ reconstruction include CCG, metatarsal, fibula, distraction osteogenesis, and the posterior border of the ascending ramus (sliding osteotomy).

- Advantages of CCG include a low complication rate, the ability to shape the cartilage to the anatomy of the glenoid fossa, the capacity for remodeling into an adaptive mandibular condyle, and possessing an adaptive growth center for growing patients. CCG should not be used in areas of recurrent ankylosis or active infection.

- The CCG is the graft of choice for growing pediatric patients.

- Prior to any surgical intervention, a thorough CT evaluation should be performed to evaluate both the involved and uninvolved joint to identify areas of potential abnormalities and/or restrictions to movement.

- For patients with moderate to severe dysgnathia, a prefabricated occlusal splint should be used in order to establish ideal intraoperative and postoperative occlusion.

- When performing gap arthroplasty on ankylosed joints, the ankylosed mass is typically removed en bloc. For larger ankylosed masses (Figure 33.1; see also Figure 33.2), the mass is sectioned and removed in smaller segments (Figure 33.3). When removing ankylosed masses, a line of separation or cleavage plane is frequently present between the ankylosed mass and the glenoid fossa. If present, a periosteal elevator can be placed within this plane to identify the caudal aspect of the glenoid fossa and to allow for the dissection of the ankylotic mass from the glenoid fossa. The removal of the ankylotic mass from the medial aspect of the glenoid fossa is imperative to allow for maximal function and to minimize the risk of recurrent ankylosis.

- In ankylosis cases resulting from condyle trauma, the fractured condyles are completely removed during excision of the fibrous or bony ankylotic mass.

- When securing the CCG to the lateral ascending ramus, positional and lag screws may propagate a fracture within the CCG and distract the costal cartilage cap from the glenoid fossa. Plate fixation will minimize the risk of fracture of the CCG by acting as a washer and distributing the forces of compression along the lateral surface of the CCG.

- When possible, the native disc should be preserved and maintained. Temporalis muscle fascia flaps, temporoparietal galea flaps, and dermis grafts can also be used to line the glenoid fossa. Well-contoured cartilage caps that articulate ideally within the glenoid fossa often require no lining.

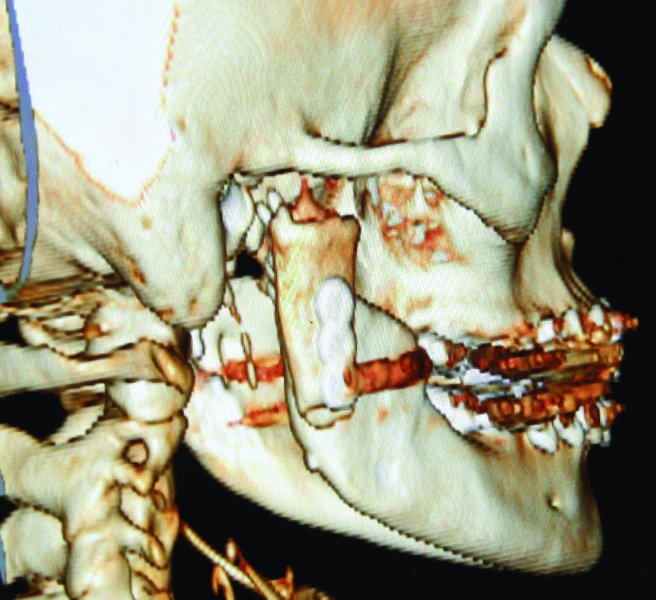

Figure 33.11. Postoperative computed tomography scan demonstrating costochondral grafts secured to the lateral aspect of the ascending ramus with articulation within the glenoid fossa.

Figure 33.12. Postoperative 3D reconstruction demonstrating placement of the right costochondral graft.

Figure 33.13. Postoperative 3D reconstruction demonstrating placement of the left costochondral graft.

References

- El-Sayed, K.M., 2008. Temporomandibular joint reconstruction with costochondral graft using modified approach. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 37, 897–902.

- Kaban, L.B., Bouchard, C. and Troulis, M.J., 2009. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 67, 1966–78.

- Khadka, A. and Hu, J., 2012. Autogenous grafts for condylar reconstruction in treatment of TMJ ankylosis: current concepts and considerations for the future. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 41, 94–102.

- Medra, A.M., 2005. Follow up of mandibular costochondral grafts after release of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joints. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 43, 118–22.

- Saeed, N.R. and Kent, J.N., 2003. A retrospective study of the costochondral graft in TMJ reconstruction. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 32, 606–9.

- Sahoo, N.K., Tomar, K., Kumar, A. and Roy, I.D. , 2012. Selecting reconstruction option for TMJ ankylosis: a surgeon's dilemma. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 23, 1796–801.

- Vega, L.C., Gonzalez-Garcia, R. and Louis, P.J., 2013. Reconstruction of acquired temporomandibular joint defects. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 25, 251–69.