CHAPTER 51

Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap

Eric R. Carlson and Andrew Lee

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Tennessee Medical Center, University of Tennessee Cancer Institute, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA

A soft tissue reconstructive surgical procedure that provides oral lining and facial cover of soft tissue defects. Referred to as the workhorse flap of head and neck reconstruction.

Indications

- Immediate reconstruction of oral lining (floor of mouth, buccal mucosa, and mandibular gingiva) and lower third facial/neck cover in patients undergoing ablative cancer surgery of the oral and maxillofacial region

- Delayed reconstruction of oral lining and facial/neck cover tissue in patients who have experienced avulsive trauma of the oral and maxillofacial region

- Reconstruction of oral lining and facial/neck cover in patients undergoing surgical treatment of radiation tissue injury of the oral and maxillofacial region

- Immediate muscular coverage of the carotid artery in patients who have undergone radical and modified radical neck dissections

- Salvage reconstructive surgery for failed free microvascular flap reconstruction of the oral and maxillofacial region

- Primary method of reconstruction of the oral and maxillofacial region where systemic medical comorbidity (i.e., uncontrolled diabetes, cardiopulmonary failure, or renal insufficiency) precludes the execution of a microvascular flap for reconstruction

Contraindications

- Excessive trauma sustained by the subclavian artery during the placement of a central venous catheter, whereby the integrity of the thoracoacromial artery has been compromised. Preoperative angiography is indicated when an injury is suspected to this primary pedicle that might result in inadequate vascularity to the pectoralis major muscle if myocutaneous flap development were performed

- Midfacial, upper third facial, and maxillary soft tissue defects where the arc of rotation and length of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap are insufficient

- Excessively large skin paddle required to perform the reconstruction. Women are able to undergo pectoralis major myocutaneous flap development with larger skin paddles than men due to the redundancy of the female breast. Skin grafting the chest wall is not advisable in the event of inability to achieve primary closure of the chest wall due to the likely development of postoperative costochondritis

Anatomy of the Pectoralis Major Muscle

Pectoralis Major Muscle

A broad, flat, fan-shaped muscle that covers the pectoralis minor, subclavius, serratus anterior, and intercostal muscles on the anterior thoracic wall.

The muscle originates from the medial one-half to two-thirds of the clavicle, the lateral portion of the entire sternum and the adjacent cartilages of the first six ribs, and the bony portions of the fourth, fifth, and sixth ribs. The muscle inserts on the greater tubercle of the humerus.

Three major segmental subunits of the pectoralis muscle have been described: a clavicular segment, a sternocostal segment, and a laterally placed external segment. The clavicular segment arises from the midclavicular area, receives its blood supply from the deltoid branch of the thoracoacromial artery, and is innervated by branches of the lateral pectoral nerve. The sternocostal segment accounts for most of the pectoralis major muscle and receives its blood supply from the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery with its nerve supply from the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. The external segment has a variable blood supply with contributions from the lateral thoracic and thoracoacromial artery.

The motor action of the pectoralis major muscle is to medially rotate and adduct the humerus. The muscle is innervated by the medial and lateral pectoral nerves that develop from the brachial plexus. Development of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is of little functional ill consequence as the latissimus dorsi muscle compensates for otherwise lost adductor activity.

Thoracoacromial Artery

The muscle's primary blood supply is from the thoracoacromial artery that arises as the second branch of the axillary artery coming off the subclavian artery. Secondary pedicles include the lateral thoracic and superior thoracic arteries.

Deltopectoral Groove

This represents the anatomic junction of the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles through which the cephalic vein passes.

Bony landmarks of importance in the development of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap include the clavicle and the manubrial notch and xiphoid process that demarcate the midline of the chest wall.

Soft tissue landmarks of importance in the development of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap include the nipple and, in the case of a woman, the inframammary crease.

Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap Surgical Technique

- Development of the recipient tissue bed prior to the development of the myocutaneous flap is paramount in the performance of reconstruction with the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. In the case of immediate reconstruction of an ablative soft tissue defect (Figure 51.5), the delivery of the cancer specimen (Figure 51.4) permits a quantitative measurement of the defect with the subsequent design of this exact skin paddle size on the chest wall. In the case of an avulsive traumatic defect, the release of scar tissue in the recipient tissue bed permits a more accurate appreciation and measurement of the skin paddle requirement and subsequent design of this exact skin paddle size on the chest wall. Simultaneous recipient and donor site surgeries may result in the development of a skin paddle that is of insufficient size to adequately reconstruct the defect.

- Following the determination of the required skin paddle size, the skin paddle is designed medial and inferior to the nipple on the chest wall. The required skin paddle size is slightly overestimated when designing the skin paddle on the chest wall so as to reduce tension on the closure at the recipient site, thereby reducing possible dehiscence at the recipient site (Figure 51.6). In the case of a woman, the inferior aspect of the skin paddle is designed in the inframammary crease.

- A curvilinear incision is designed that connects the medial aspect of the skin paddle to the region approximating the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- The dissection is initiated by incising the skin and subcutaneous tissues about the proposed incision. The deeper dissection is performed with the electrocautery unit to the level of the pectoralis major muscle fascia that is maintained on the ventral aspect of the muscle (Figure 51.7). This dissection is carried superiorly to the region of the clavicle, supero-laterally to the deltopectoral groove, infero-laterally to the free margin of the pectoralis major muscle, and medially to the region of the lateral aspect of the sternum.

- In the area of the skin paddle, the deep dissection is performed so as to not undermine the skin paddle and risk its viability. The circumferential dissection of the skin paddle is completed down to the pectoralis fascia superiorly and down to the rectus abdominus fascia inferiorly. Often, the inferior dissection will divulge that the skin paddle is not supported by underlying pectoralis major muscle. This realization does not jeopardize the skin paddle's viability. The skin paddle is temporarily sutured to the underlying pectoralis major fascia and possibly to the inferiorly located rectus abdominus fascia.

- The elevation of the myocutaneous flap is initiated by elevating the rectus abdominus fascia off of its muscle that inserts on the inferior aspect of the sixth rib. The entirety of the pectoralis major muscle is elevated off the ribs’ superficial surfaces as well as the intercostal muscles that are encountered thereafter. This technique is continued from the free margin of the pectoralis major muscle laterally to the origination of the muscle medially. In general, approximately 1 cm of pectoralis major muscle is maintained on the lateral aspect of the sternum in the development of the myocutaneous flap. Further superior dissection will identify the pectoralis minor muscle. In addition, as the myocutaneous flap is mobilized superiorly, the axial vessels will be identified within the deep surface of the muscle. Retraction of the muscle during its elevation is important to avoid inadvertent trauma to the primary and secondary pedicles of the flap.

- Perforators from the intercostal artery coursing through the intercostal muscles and perforators from the internal mammary artery coursing in the parasternal region should be identified and properly coagulated or ligated during the dissection to prevent postoperative bleeding.

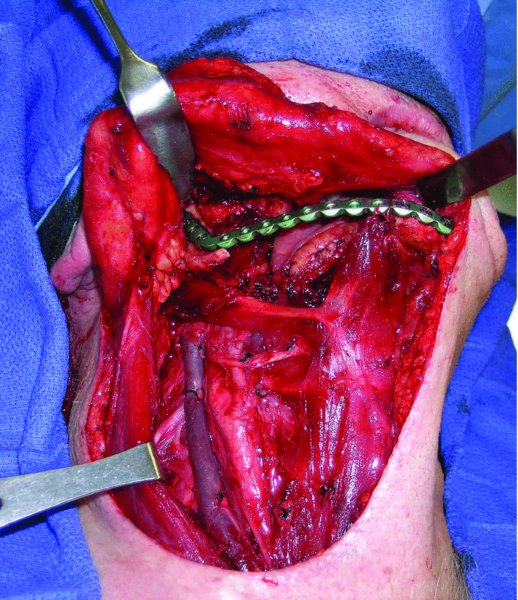

- The insertion of the pectoralis major muscle at the greater tubercle of the humerus will be identified supero-laterally. The cephalic vein is identified in the deltopectoral groove. The disinsertion of the pectoralis major muscle is performed in an incremental fashion with the electrocautery unit (Figure 51.8). Complete disinsertion is typically required to realize an effective arc of rotation of the myocutaneous flap into the recipient tissue bed (Figure 51.9).

- A bipedicled neck flap is required so as to pass the myocutaneous flap into the neck and ultimately into the oral cavity. This bipedicled neck flap serves to communicate the dissection of the neck with that of the chest wall. It is created deep to the platysma muscle and superficial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and clavicle. The bipedicled neck flap is created in this surgical plane from the neck approach as well as from the chest wall approach, after which the communication is created that must have the breadth of five fingers so as to not constrict the flap's vasculature.

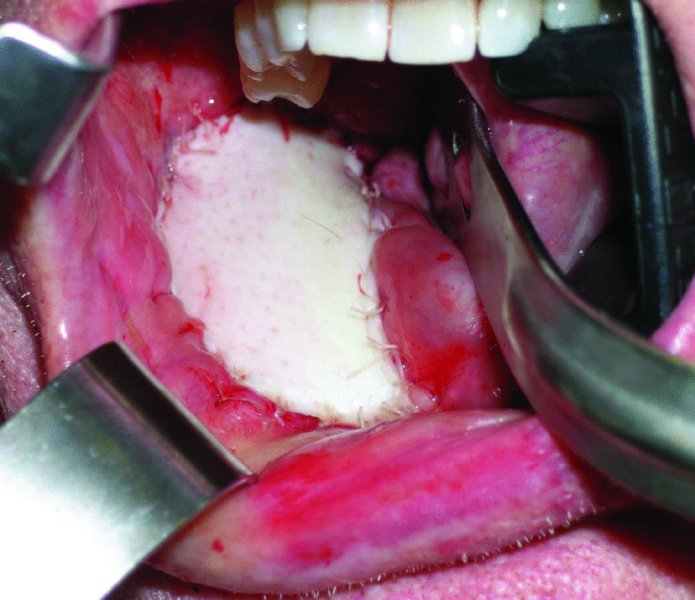

- The myocutaneous flap is passed deep to the bipedicled neck flap and into the oral cavity (Figure 51.10). The previously placed skin paddle sutures are removed prior to initiating the closure of the skin paddle to the oral mucosa to complete the reconstruction (Figure 51.11).

- Two suction drains are placed in the chest wall donor site. One is typically oriented vertically toward the disinsertion, and one is placed in a dependent horizontal fashion. The chest wall is closed in anatomic layers with staples placed at the skin surface.

- Two suction drains are commonly placed in the neck. If a neck dissection was performed, one drain will be placed in the carotid sheath area, and one drain will be placed in the submental triangle. The neck is closed in anatomic layers with sutures placed at the skin surface.

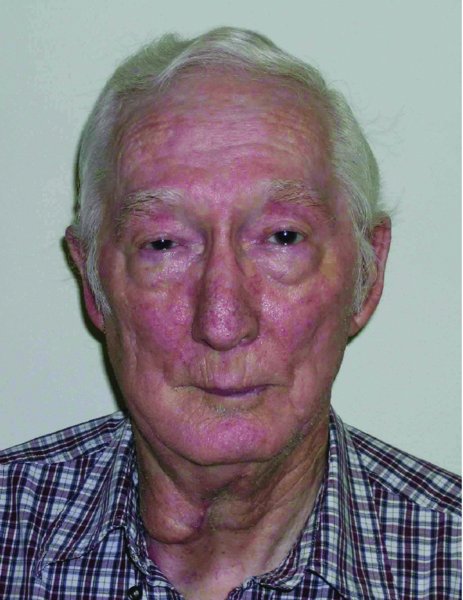

Figure 51.1. An 81-year-old patient presents with a chief complaint of a mass of his right lower jaw.

Figure 51.2. 3 cm biopsy proven SCCA of the right mandibular gingiva and underlying mandible. There was no evidence of cervical lymph node on physical or radiographic examinations. The SCCA was classified as a T4N0M0 based on the TNM classification by the AJCC.

Figure 51.3. Orthopantogram demonstrates bony involvement of the right posterior mandible.

Figure 51.4. Medial aspect of composite resection specimen of the right mandibular gingiva, mandible, and elective neck dissection.

Figure 51.5. Hard and soft tissue defect after ablative surgery. An oral soft tissue defect of 6 cm × 3.5 cm is present after composite resection.

Figure 51.6. Proposed skin paddle designed on the chest wall with slight overcorrection, 7 cm × 4 cm.

Figure 51.7. The dissection was performed at the donor site while maintaining the pectoralis fascia on the pectoralis major muscle.

Figure 51.8. The muscle is disinserted at the greater tubercle of the humerus, and the cephalic vein can be seen in the deltopectoral groove.

Figure 51.9. Superior mobilization of the myocutaneous flap.

Figure 51.10. Flap passed through the bipedicled neck tunnel and ultimately into the oral cavity.

Figure 51.11. Oral defect primarily reconstructed with the skin paddle from the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap.

Postoperative Management

- Following pectoralis major myocutaneous flap reconstruction, patients typically maintain their endotracheal intubation and ventilator support for at least 12 hours postoperatively due to the magnitude of these surgeries.

- Intravenous antibiotics are routinely ordered postoperatively for a time period determined by the preference of the surgeon.

- Perioperative corticosteroid administration is of benefit to patients due to the excessive swelling that otherwise occurs. If significant, oral swelling can prolong the time required to maintain the endotracheal tube postoperatively and may increase the likelihood of postoperative tracheotomy.

- Suction drains are maintained until trends in their drainage identify the ability to remove the drains. This is typically 10 days.

- The skin staples are typically removed in 10 days.

- Patients are typically fed via a nasogastric feeding tube that is maintained until acceptable healing without signs of infection or wound breakdown is realized within the oral cavity. This is commonly a 2-week period postoperatively.

Early Complications

- Bleeding: May result from ineffective coagulation or ligation of perforators from the intercostal or internal mammary vessels. In addition, ineffective coagulation of the disinsertion site at the greater tubercle of the humerus can lead to significant postoperative bleeding. When a postoperative hematoma is identified, a return to the operating room is required for evacuation of the hematoma and proper coagulation of the offending vessel(s).

- Infection: Minimized with meticulous adherence to sterile techniques, the use of perioperative antibiotics, and copious irrigation of the oral cavity, neck, and chest wall. Treatment is via drainage with culture-directed antibiotic therapy.

- Dehiscence: this complication is commonly noted and probably related to movement of the oral tissues during function. Wound dehiscence is managed with conservative measures, including local wound care. Complete healing is realized as long as exposure of the underlying reconstruction bone plate does not occur. Placing a skin paddle of slightly larger size than is required will decrease tension on the closure and decrease the likelihood of dehiscence postoperatively.

Late Complications

- Skin paddle necrosis: Marginal or complete skin paddle necrosis is occasionally observed. Most cases occur in women with pendulous breasts, whereby a significant volume of fat separates the skin paddle and underlying muscle of the myocutaneous flap.

- Lip incompetence: The weight of the myocutaneous flap is such that inferior migration of the lower lip may occur during healing. As such, maintenance of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve during neck dissection is beneficial to maintain motor innervation of the lower lip. The loss of motor innervation of the lower lip and the weight of the myocutaneous flap will discourage lip competence in the postoperative period. Failure to maintain lip competence compromises the patient's ability to successfully take an oral diet. This problem becomes clinically noticeable with the resolution of surgical edema and the development of scar tissue in the recipient tissue bed.

- Recurrent disease: The bulk of the pectoralis major muscle may hide early recurrence in the neck that might otherwise be readily detectable by palpation. As such, obtaining computed tomograms might be indicated in patients who underwent the placement of a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap whose neck dissection specimens showed microscopic evidence of metastatic nodal disease with or without extracapsular extension.

Key Points

- The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is supplied primarily by the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery and secondarily by the lateral thoracic artery and the superior thoracic artery. The incorporation of primary and secondary pedicles in the myocutaneous flap reduces the complication of partial or total loss of the skin paddle. This is a departure from the originally described technique for the development of this myocutaneous flap that was based exclusively on the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery.

- The skin paddle of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is able to reconstruct oral lining and facial cover, or it can be split to simultaneously reconstruct both.

- The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap is ideally suited to reconstruct oral soft tissue in the floor of mouth, ventral tongue, mandibular gingiva, and inferior buccal mucosa and skin in the lower third of the face. This flap does not practically possess an acceptable arc of rotation or length to reconstruct oral mucosa in the maxillary gingiva or palate or the skin of the upper two-thirds of the face.

- A quantitative assessment of the ratio of the chest wall length to the neck length is also important to determine preoperatively when considering the selection of a myocutaneous flap for oral and maxillofacial reconstruction. It is important to ensure that the distance from the proposed skin paddle to the clavicle exceeds the distance from the recipient tissue bed to the clavicle before committing to the use of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. A long neck and relatively shorter chest wall length will impair the arc of rotation of this flap into the recipient tissue bed.

- The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap has added value in its ability to cover the carotid artery when performed in conjunction with a radical or modified radical neck dissection where exposure of the carotid artery occurs.

- The skin color of the chest wall is generally not favorable compared to the upper neck and facial skin, such that a color mismatch will occur when performing a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap for facial/neck cover reconstruction.

Figure 51.12. Postoperative evaluation of the patient shows acceptable facial form and the obvious prominence of the pectoralis major muscle in the neck.

Figure 51.13. Well-healed skin paddle to intraoral defect.

References

- Ariyan, S., 1979. Further experiences with the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap for the immediate repair of defects from excisions of head and neck cancers. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 64, 605–12.

- Ariyan, S., 1979. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap: a versatile flap for reconstruction in the head and neck. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 63, 73–81.

- Carlson, E.R., 2003. Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 15, 565–75.

- Carlson, E.R. and Layne, J.M., 1997. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of soft tissue oncologic defects. Atlas of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 5, 15–35.

- Chiummariello, S., Iera, M., Domatsoglou, A. and Alfano, C., 2010. The use of pectoralis major myocutaneous flap as “salvage procedure” following intraoral and oropharyngeal cancer excision. Il Giornale di Chirurgia, 31, 191–6.

- Hsing, C.Y., Wong, Y.K., Wang, C.P., Wang, C.C., Jiang, R.S., Chen, F.J. and Liu, S.A., 2011. Comparison between free flap and pectoralis major pedicled flap for reconstruction in oral cavity cancer patients—a quality of life analysis. Oral Oncology, 47, 522–7.

- Kekatpure, V.D., Trivedi, N.P., Manjula, B.V., Mathan Mohan, A., Shetkar, G. and Kuriakose, M.A., 2012. Pectoralis major flap for head and neck reconstruction in era of free flaps. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 41, 453–7.

- Marx, R.E. and Smith, B.R., 1990. An improved technique for development of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 48, 1168–80.

- McLean, J.N., Carlson, G.W. and Losken, A., 2010. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap revisited: a reliable technique for head and neck reconstruction. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 64, 570–3.

- Moloy, P.J. and Gonzales, F.E., 1986. Vascular anatomy of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 112, 66–9.

- Ossoff, R.H., Wurster, C.F., Berktold, R.E., Krespi, Y.P. and Sisson, G.A., 1983. Complications after pectoralis major myocutaneous flap reconstruction of head and neck defects. Archives of Otolaryngology, 109, 812–14.

- Shah, J.P., Haribhakti, V., Loree, T. and Sutaria, P., 1990. Complications of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. American Journal of Surgery, 160, 352–5.