Chapter 1

Before Hollywood

New media always grow out of existing media, and film is no exception. Both early film technology and storytelling methods developed from older media. Most early film projectors, for example, were simply magic lantern slide projectors with jury-rigged film reels bolted on. The new technology (film) was grafted onto the older technology (slides). The aesthetic and narrative styles of early films were similarly lifted from newspaper comics, photography, vaudeville, and magic lantern shows. Film was never a new medium but always an outgrowth and mixture of many others.

From the phonograph to the Vitascope

Indeed, when inventor Thomas Edison set his company to work designing a film camera, he wrote that his goal was to do “for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear.” Edison had already developed a successful phonograph business, and he wanted to replicate it with moving pictures, adapting the phonograph experience and commercial model to the visual realm. The phonograph division of the Edison Manufacturing Company specialized in installing phonographs in storefront parlors, where patrons could move from one machine to the next, listening to popular songs or speeches recorded on Edison’s own record label.

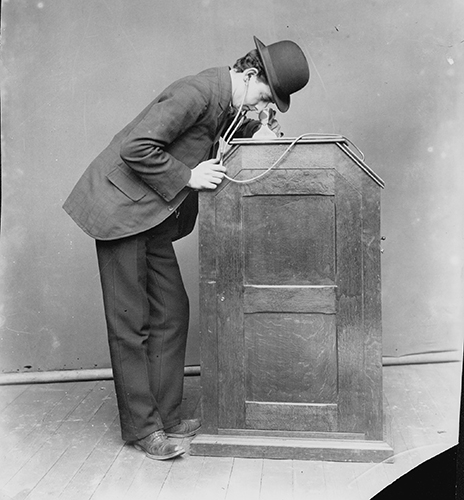

Following that model, Edison’s company developed peep-show viewers called Kinetoscopes, which displayed a minute or so of film to a patron who looked through the viewfinder. Popular subjects included boxing matches and passion plays, which could be broken down into scenes that unfolded as viewers moved from one Kinetoscope to the next, depositing coins at each turn. Other Kinetoscope films took advantage of the peep-show design, showing scenes that looked as if they had been filmed through a keyhole. Edison never lost sight of his goal: joining image and sound. He eventually filed a patent for a Kinetophone to display synchronized images and sounds, although only a few were made, and they never worked very well.

1. Boxing films were popular on Edison’s peep-show viewer, the Kinetoscope, before he abandoned it in favor of movie projection. Some critics have argued that mobile phones bring us back to the Kinetoscope’s individual viewing experience.

Edison was far from the only inventor working to develop motion picture technology. A number of inventors in the United States and Europe simultaneously devised similar machines, often learning from each other. Unlike Edison, however, most of his rivals had dreams of projecting moving images onto large screens, not showing them to individuals peering through small holes. (Later commenters have mused that watching movies on portable devices like mobile phones takes us full circle, back to Edison’s original peep-show model.)

When a projector designed by two French photographic equipment company owners, the Lumière brothers, began to be used in vaudeville houses in New York in 1896, it quickly became clear that projected images were a hit with audiences. Edison realized that he needed to rethink the direction of his film business. Rather than return to the laboratory, Edison bought the rights to a projector designed by two recent engineering school graduates, Thomas Armat and Charles Frances Jenkins, marketing the device as “Edison’s Vitascope,” with a small plaque crediting the original designers.

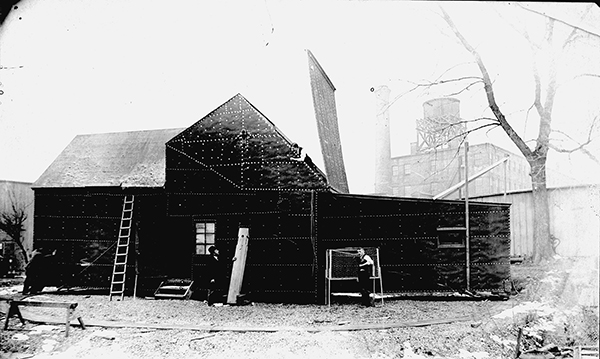

As he had with the phonograph, Edison went into the film production business to create content for his machines. He built a small film studio, known as the Black Maria, on the grounds of his West Orange, New Jersey, laboratory. Black Maria was slang for the police trucks used to transport prisoners, and it suggested the unseemly subjects being filmed—or at least that was how they were perceived. Many of the Edison Company’s earliest films were of vaudeville performers, who came up from New York to have their routines recorded for the Wizard of Menlo Park, as Edison was known. A succession of strong men, dancers, and animal acts performed within the black, tar-covered walls of Edison’s studio. The only light source was the sun, which shone in through the retractable roof. The entire building spun around 360 degrees to catch the light all day long. Other filmmakers built glass studios to let in the sunlight, and many films were shot outside in the direct sunlight. It would be another decade before lights were strong enough and film stock sensitive enough to allow artificial light to be used to illuminate filmed subjects. Using available light, early camera operators captured exotic vistas, newsworthy events, and scenes of everyday life, all called “actualities.”

As early as 1894 (and possibly 1893), Edison began depositing his films at the Library of Congress so that they would receive copyright protection. The company printed its films on long strips of paper—known as paper prints—and registered them as photographs with the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress. Because paper prints of so many Edison films were deposited in a government vault, they continue to exist, even though more than 90 percent of films made before 1910 have vanished.

2. Edison’s studio, the Black Maria, could spin 360 degrees to let sunlight in all day long. It was not until around 1913 that more sensitive film stock and more powerful bulbs made it possible to shoot movies using only artificial light.

The nickelodeon era

The earliest films were shown at amusement parks, vaudeville houses, and curiosity displays called dime museums. The first dedicated movie theaters, nickelodeons, began to appear around 1903. Nickelodeons were generally storefronts that had been fitted with a projector and a screen. Often they were converted saloons, and the transition from saloon to nickelodeon is significant. Saloons were spaces for working-class men to spend newly won leisure time and money. The conversion of saloons to nickelodeons indicated that working-class women and children were entering the space of public leisure entertainment. A family could stop in to a nickelodeon while shopping, stay for an hour or two, and then leave. The show of short films, however, went on all day, much like television programming would later. The mixing of genders, ages, classes, and ethnic communities in the space of the theater deterred many potential middle-class customers at first. Legislators soon took action. In New York, one provision stipulated that the lights in a nickelodeon had to be bright enough for a patron to read the newspaper, suggesting that nickelodeons might be places for middle-class leisure pursuits like reading the paper and not just a haven for pickpockets, “mashers” (sexual predators), and customers there to consume prurient images.

Although nickelodeons were potentially new democratic spaces, they were also deeply local. Films were short and could be shown in many different combinations. Musical accompaniment varied widely; one nickelodeon might have a piano player and another a jazz band playing alongside the same films. Some had actors who voiced characters and most had narrators to introduce and explain films. Whatever the setup, silent films were rarely shown silently. Many nickelodeons also had only one projector, so live entertainment or lantern slides were still used during reel changes. Nickelodeons were multimedia experiences, and viewing a movie was very different if you watched it on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, in nearby Chinatown, or halfway across the country in Chicago’s Loop. Films were mass-produced, but film viewing was far from a homogenous experience.

The short films projected in nickelodeons could be mixed and matched to produce very different experiences, and the exhibitor—the person arranging the show—was often the most creative individual behind the program. In some cases, exhibitors went on to become directors, most notably Edwin S. Porter, who rose from dime museum exhibitor to Edison’s top director (The Great Train Robbery, 1903). Nickelodeons were also an easy way to enter the emerging industry, and many Hollywood moguls began as nickelodeon owners, including Carl Laemmle (who founded Universal), Adolph Zukor (who cofounded Paramount), and Louis B. Mayer (who cofounded MGM).

Pre-1908 films have come to be known as “the cinema of attractions,” because they emphasized spectacle, motion, and shock. Filmmakers placed cameras on trains, boats, and amusement park rides to capture the pace of modern life. They filmed world leaders and famous monuments. They offered virtual travel and vicarious thrills. Edison’s 1896 film The May Irwin–John Rice Kiss, to take a popular example, remained on screens for years, and it was often repeated several times for the same audience. The film showed two portly actors engaging in a chaste kiss in a scene from a popular play, and it perfectly represented the power of film. As viewers of the film, we have a privileged close-up of the actors, a better view than even the best seat in the theater could offer. Moreover, the story is removed, offering only the most talked-about spectacle, or attraction, of the production: the kiss.

Other films played with the idea of the invisible fourth wall, separating the audience from the film. They showed salacious or dangerous scenes and then reminded the audience of their protected, voyeuristic position. A 1901 British film, The Big Swallow, for example, showed a close-up of a man walking toward the camera. Eventually the camera seems to descend down the man’s throat, and the screen turns black. Then we see a pair of legs fall into the cavernous black space. At first it appears as though the man has swallowed us—the audience—calling attention to the safe space of the theater in which no image could, in reality, physically harm us. But then we realize that the man in the film has seemingly swallowed the cameraman, and we are reminded of another displacement; we are reminded that the film is not live and was in fact filmed by an unseen technology, a camera, and by an offscreen cinematographer. Films like The Big Swallow trained early film audiences to experience the new virtuality of film and the voyeuristic experience of spectatorship.

Despite the common myth that it took years before filmmakers started telling stories, narrative films were prevalent from the earliest days of cinema. The stories were often based on existing material. Films recreated newspaper comics or old vaudeville routines. Many films required audiences to be familiar with the stories that the films illustrated, what film scholars often call “intertexts.” Early film audiences had narrators to explain the action, but it helped if you already knew the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes, for example, or King Lear, or the plots of Broadway plays. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, was the most popular American play of the nineteenth century and still a popular attraction in the early 1900s. Many companies, including Edison’s, made screen versions, staging highlights from the play for the film audience. If the audience did not know the intertexts—the novel and the play—they would be lost, although one could of course enjoy the sheer spectacle of the scenes.

Around 1908–1909, filmmaking and the film industry underwent a number of changes. Established film companies started to court a middle-class audience in order to expand the industry’s reach. Production companies made films based on novels and Broadway plays. And stories began to be told in new ways. In particular, filmmakers took over the job of narration from the live narrators in the theaters. Edison’s version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903) is a perfect example of a film made before this transformation. It is presented as a series of scenes with a cut—an edit—between each one. It is as if the curtain dropped and rose again between each shot. The filmmakers left it to the audience and the nickelodeon narrators to fill in the gaps.

Films made during the 1908–1909 change began to use a codified system of “continuity editing” to visually give the audience the most important pieces of information. Filmmakers developed a stylistic system to let audiences understand how two shots are connected in space and time while also relating characters’ thoughts and feelings.

When a character looks offscreen in one direction and we see a vista through a window in the next shot, we know that we are approximating the character’s gaze. This is called an “eyeline match.” Similarly, when a character begins to exit through a door in one shot and we pick up the same character completing the action in the next shot, we know the two shots are connected. It is a “match on action.” This stylistic code often seems natural and obvious to us, but it is in fact a human innovation, influenced by culture, technology, and history. It is the most basic but also one of the most amazing elements of film: spectators are able to construct a coherent idea of story time and space from the short fragments of film spliced together.

Other elements that helped filmmakers narrate their stories around the same time include intertitles, the cards of description or dialogue that were shown between shots. Intertitles directly usurped the job of live narrators, and they looked forward to dialogue in sound film.

Acting too saw a transformation. The exaggerated pantomime that we associate with early film became less popular during this period, and a more contained realistic style began to dominate. The broad gestures early film actors used to express emotions, as they had in the nineteenth-century theater, were replaced by subtle facial expressions glimpsed in close-up. Hungarian film theorist Béla Balázs called these close-ups “silent soliloquies.” Filmmakers had been experimenting with editing and different acting styles from early on, but this new unified style of storytelling took over very quickly.

One 1907 film, Edwin S. Porter’s The Teddy Bears, shows the industry right on the cusp of these changes. It combines two stories: the fairy tale “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” and the then-recent news story of President Teddy Roosevelt’s hunting expedition. Roosevelt started a national craze for stuffed “teddy” bears when, on a hunting trip, he spared a baby cub after orphaning it. Such was the state of early twentieth-century animal rights. In the film, Goldilocks sits in the bears’ chairs, eats their porridge, and is sleeping in the baby bear’s bed when the bear family returns. Goldilocks flees and is chased by the bears, only to run into President Roosevelt. Roosevelt, the hero of the story, shoots the mother and father bear, shackles the baby as a present for Goldilocks, and, in addition, gives Goldilocks a collection of stuffed teddy bears she had admired in the house.

Scholars have puzzled over the film’s meaning for decades. But one thing is clear; it combines the elements of the pre- and post-1908 cinematic storytelling. Like the early nickelodeon films, it requires knowledge of other stories. It even contains a keyhole film within it: Goldilocks spies on the stuffed teddy bears through the keyhole of a wooden door while they do acrobatic stunts in a still-impressive animated stop-motion sequence. But the film also looks forward: the acting alternates between the histrionic pantomime of early cinema and the realistic mode of later films. The editing style also reveals the film to be stuck between two aesthetic paradigms. In the opening sequence of the film each shot is a separate scene, but the final chase sequence relies on the direction of the action to connect shots within a scene. Although the moral of The Teddy Bears feels foreign to us today, the visual storytelling method is more familiar than many of its antecedents.

The Trust and the independents

In addition to undergoing a major change in storytelling methods between 1907 and 1909, the American film industry was also restructured. The first film companies in the United States engaged in fierce competition. The larger companies hired away talent from their competitors. Producers “duped” (copied) each other’s films and sold them as their own. The leaders of the industry also attempted to monopolize the market by asserting sweeping intellectual property claims. Edison, in particular, aggressively pursued litigation in an attempt to wipe out the competition, and, for a brief period, his tactics proved successful.

Edison held three broad patents on motion picture technology, and in court cases and the trade press he regularly claimed that all moviemaking endeavors were built on his inventions. Eventually, Edison’s patent claims were all overturned in court, although he reapplied and managed to claim credit for a few minor adjustments. But court losses did not stop Edison or his company from dragging other companies through legal battles that they could not afford to fight. It reveals a lot about the centrality of litigation to Edison’s business that the head of his legal department, Frank Dyer, rose to be the head of Edison’s entire film division.

Edison’s most formidable competitor was a company called American Mutoscope and Biograph, or Biograph for short. Biograph’s camera and projector had been designed in part by Edison’s former chief of motion picture development, W. K. L. Dickson, and the company claimed that its equipment was significantly different from Edison’s. More importantly, Biograph held the exclusive rights to one of the key film patents: the Latham loop. Patented by chemistry professor Woodville Latham, the Latham loop simply involves leaving a bit of slack in the filmstrip before and after it enters the gate of the projector, where light shines through it. One reason that early films were so short is that tension would build up in the projector, and the celluloid would break. The Latham loop absorbed the tension and allowed filmmakers to make longer films. No exhibitor could show a film without using the Latham loop, and it became one of the key pieces of intellectual property in the early American film industry.

In December 1908, Edison and Biograph agreed to pool their patents and set up the Motion Picture Patents Company (the Trust), a group of companies that also included celluloid manufacturer George Eastman and a number of US and European film producers and distributors. The Trust agreement was a Faustian pact for distributors and exhibitors. They gained access to the Trust’s exclusive technology and films, but they lost their autonomy and were forced to pay licensing fees that made it hard to turn a profit.

The Trust sought to standardize the industry, making film into a commodity rather than a unique good. No two films have exactly the same audience appeal, but the Trust treated all films equally. Producers had to meet a quota, and films were released on a set day of the week. Films were sold in reels, and every reel was sold at the same price, like pounds of sugar. Distributors also had to buy films in advance, sight unseen.

In its efforts to standardize the industry, the Trust even embraced censorship. Starting in 1909, the Trust agreed to let the National Board of Censorship, later renamed the National Board of Review, stamp each film with its seal of approval. As part of the effort to attract middle-class patrons and deter politicians eager to win votes by imposing restrictions on movie theaters, exhibitors wanted to make themselves appear more respectable. They agreed to show only films that had been approved by the National Board of Review. And once the Board had an exclusive agreement with the Trust, even more exhibitors became exclusive Trust licensees.

The Trust held a tight grip on every aspect of the industry, from the sale of film stock to the approval of the censor board. But standardization deterred innovation and bred dissention. The independents who opposed the Trust incorporated as Independent Moving Pictures (IMP) only ten days after the Trust itself. Led by film distributor Carl Laemmle, the independents bought film stock from the Lumière brothers’ company in France, and they established their own network outside of the Trust’s. The Trust had fixed its business methods just as the industry was in the process of changing, and it could not keep up with audience demands. The independents, on the other hand, exploited innovations that brought in the middle-class audiences so important to the next phase of industry growth.

First, the independents started to make feature films. Where the Trust insisted on selling films by the reel (about fifteen minutes each), the independents’ longer multireel films were better suited to the adaptations of plays and novels that appealed to middle-class patrons. The independents also imported spectacular Italian epics, which enjoyed a vogue in the United States at the time. The Trust members did release some films with stories that stretched across multiple reels, but in general they missed the opportunity to move into feature film production.

Second, the independents realized the value of movie stars. Movies come and go, but the actors continually reappear. Edison’s first instinct had been to bring vaudeville stars to his studio and capture their performances on film. But many Trust members resisted the idea of promoting movie stars or even crediting the actors in films. They knew that once actors had marquee value, they would demand higher salaries. Audiences, however, clamored to know more about the faces they saw every week.

Reporters began to refer to Biograph’s popular actress Florence Lawrence as the Biograph Girl long before audiences knew her name. Carl Laemmle hired Lawrence for IMP in 1909, and he promoted her as a movie star, circulating sensational stories about her private life and forthcoming films. Other independent producers capitalized on the demand for stars by luring stage talent to the screen. Nickelodeon owner Adolph Zukor based his production company on the rise of star appeal, calling it the Famous Players Film Company and importing a French film about Queen Elizabeth I starring the legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt.

As quickly as the Trust gained control of the industry, it lost its grip. It is as if the Hollywood studios were replaced by internet video companies in the space of only a few years. In addition to being left behind in the move to feature films and the star system, the Trust experienced a number of legal and operational blows. In 1911, the Eastman Company’s agreement with the Trust ended, and it began to supply film stock to the independents. Then the Latham Loop patent expired, and Trust member Kalem lost a landmark copyright case.

Backed by the legal resources of the Trust, Kalem defended its right to adapt books and plays without permission or payment. Most film companies before the Kalem decision specialized in unauthorized adaptations. It was not clear whether filmmakers needed permission to create filmed versions of popular works of literature, and they created adaptations of the bestselling novels and Broadway shows at will.

The case reached the Supreme Court, where the justices decided that film producers do in fact need permission to adapt works from other media. The resolution of the case initiated a race for film companies to strike exclusive arrangements with publishers and producers. The Trust members were outmaneuvered by the independents, who grabbed up the best partnerships, and by 1913 the Trust had been all but supplanted by the independents. In 1916 the Trust was found to be in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and broken up. This was the final nail in the coffin for an organization that quickly went from total control of the US film industry to being a calcified relic unable to meet market demands.