Chapter 2

The studio system

Carl Laemmle, Adolph Zukor, William Fox, and the other independents overthrew the Trust, only to form their own closely linked group of industry power brokers—what economists call an oligopoly. The independents moved to California and founded the Hollywood studios, including Universal, Paramount, and Fox. Ever since, Hollywood has been dominated by eight or so companies, although the ranks of major studios have been shuffled many times. Much like the Trust, the Hollywood studios set out to standardize the industry through corporate control and risk management strategies. But Hollywood has proven to be more resilient than Edison and his partners.

The birth of the studios

Even before the Trust fell apart, the independents relocated film production from New York and New Jersey to Los Angeles. The story that the independents moved west to escape Edison’s clutches is often repeated, but the real reasons were much more practical (and Trust members were actually some of the first studios to reach the West Coast). Most movies were still shot using sunlight. Studios searched for longer winter days in Florida, Mexico, and even Cuba, but Los Angeles proved to be the best option. In Los Angeles, producers enjoyed good weather all year long, and within a few hours they could reach a wide variety of locations, traveling to the desert, beach, mountains, and farm country of southern California. Los Angeles was also a non-union town, and the studios could avoid the expenses of organized labor, at least until film technicians unionized under the Studio Basic Agreement of 1921. All of the studios continued to maintain finance offices in New York, which they consulted daily, and some film production continued on the East Coast, too, largely to take advantage of Broadway talent. But by 1922, 84 percent of American film production was based in the Los Angeles area.

A number of mergers in the 1910s led to the consolidation of the Hollywood studios. As they became vertically integrated, combining every aspect of filmmaking and delivery, production companies joined with distributors and theater chains as well. Distributor W. W. Hodkinson, for example, merged several statewide distributors to form the first national chain specializing in feature films, the Paramount Pictures Corporation.

Paramount attracted top feature film producers Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky, who had recently hired a new director named Cecil B. DeMille. Eventually, Paramount merged with its producers and theater owners (known as exhibitors), and together they became a powerful entity able to bully the exhibitors who were not already in its network. Exhibitors relied on Paramount’s stable of stars and exclusive adaptation deals with Broadway companies, and Paramount insisted that theater owners rent the studio’s entire season of films or nothing, a practice known as “block booking.” Since the theater owners needed to commit to the films even before many of them had been shot, they were booked “blind,” sight unseen, as well. The Supreme Court eventually banned the practice of block booking as anticompetitive, but not until after World War II.

Big budget “A” movies would premiere at the top movie palaces like the Strand Theater in Times Square, where they were accompanied by live performances, orchestras, and often product giveaways. After a period of time, the films moved on to the lower rung of theaters, where they were shown with less fanfare but at a cheaper price. In the industry parlance of the time, the films “cleared” their “zones,” and it could take up to two years for a film to make its way through all of the zones before finally ending its run at a rural movie house. In fact, one large collection of previously lost films was discovered buried under an ice skating rink in Canada, where they had been deposited and unwittingly preserved in the cold ground after completing their long run through the North American theater circuit.

The studios’ reach extended far beyond the United States, and after World War I Hollywood became the global industry leader that it remains. Before the war, France had dominated the world’s film market, with Italy a distant second. European film companies, however, were forced to reduce their operations during the war, turning over personnel and facilities to the war effort and leaving theaters with little to show after the armistice.

As the European film industries rebuilt, Hollywood studios filled the vacuum. They set up international distribution subsidiaries and flooded screens in Europe and throughout the world with American films. When one of Hollywood’s biggest rivals in the 1920s, the German studio Ufa, ran into financial trouble, Paramount and MGM bailed it out with a $4 million loan that ensured the two Hollywood studios would get distribution priority in Germany. They called the new venture Parufamet.

To expedite international distribution, many Hollywood films were shot with two cameras in order to produce dual negatives. Once the negatives were cut, one set would remain in Los Angeles to strike prints for domestic distribution, and the second would be sent to London, the hub of international distribution. Hollywood’s international revenues continued to rise, and by 1953 international sales surpassed domestic box office profits.

Hollywood’s global dominance caused a crisis in Europe, where a number of countries sought to protect their markets from American saturation. Germany, England, and other countries imposed quotas on the importation of Hollywood films, and eventually European countries banded together to attempt to rival America. Under the auspices of the League of Nations, the Film Europe movement promoted European cinema while blocking Hollywood. The United States responded by setting up a State Department film office to negotiate better trade agreements for Hollywood. The US Congress also passed the Webb-Pomerene Act (1918), allowing Hollywood and other industries to work together overseas in ways that would have constituted illegal collusion in the United States.

In 1922 the studios started their own organization, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), run by former postmaster general Will Hays. Hays and the MPPDA later became known as Hollywood’s censors, but in the early 1920s, working from his New York office, Hays lobbied Congress on Hollywood’s behalf, while the MPPDA’s international division pushed for smoother global distribution.

Hays also worked to redefine Hollywood’s image, highlighting the central role of films in spreading American culture and products globally. “Every foot of American film,” Hays often repeated, “sells $1.00 worth of manufactured products some place in the world.” In other speeches, Hays claimed, “The motion picture carries to every American at home, and to millions of purchasers abroad, the visual, vivid perception of American manufactured products.”

Ironically, what became the classical Hollywood style of filmmaking had been an international style before World War I. Films circulated rapidly, and filmmakers learned from each other in a global conversation about film art. But once Hollywood dominated world film distribution, European countries began to develop new national styles to distinguish their films in the market. There are many cultural, political, and aesthetic reasons for the emergence of German Expressionist film, French Impressionist film, and other national styles in the 1920s. But one motivation clearly was finding a way to stand apart from and compete with Hollywood.

Back in Los Angeles, the new moguls restructured the studios, rationalizing filmmaking and turning it into an art that could be practiced on an industrial scale. Many of the changes to film production methods were pioneered by the precocious producer Thomas Ince. Ince made some of the most important films of the 1910s, including The Italian (1915) and Civilization (1916). He also owned a large studio, Inceville, for several years, before embarking on a series of partnerships with other moguls. Ince did all of this before he died at the age of forty-two, just a few days after celebrating his birthday on William Randolph Hearst’s yacht. Ince officially died of heart failure, but the legend that he died from bullet wounds inflicted by Hearst continues to stimulate the imaginations of historians, novelists, and filmmakers.

Before Inceville, film studios tended to have autonomous teams of collaborators who came up with ideas and brought them to fruition, like individual chemistry laboratories working independently under the same roof to share overhead costs. This was how D. W. Griffith worked at Biograph, where his close-knit production unit included cameraman Billy Bitzer and actresses Lillian and Dorothy Gish.

Inceville, on the other hand, was a top-down and efficient system. Ince simultaneously oversaw five shooting stages. Every film was preceded by a “continuity script” that laid it out shot by shot. With a detailed blueprint, every aspect of production could be managed more systematically. Scenes could be filmed out of sequence, and actors and other personnel only had to appear on sets when they were needed. Film crews became highly specialized, so there was an economical division of labor. Soon, all of the studios became moviemaking factories—dream factories, as they were sometimes called.

Although the moguls who built the studios were all men, in its early days, Hollywood had many women working on both the creative and business sides of the industry. Some of Hollywood’s most prolific and successful screenwriters were women, including Anita Loos, Louis Weber, and two-time Academy Award–winner Frances Marion. Weber also had a successful directing career, and Alice Guy-Blaché, who owned her own production company, is said to have directed over one thousand films stretching from 1890s French shorts to 1920s American features. Screenwriter June Mathis became one of the most powerful executives in the industry, holding high-level positions at Metro and Goldwyn Pictures (both would later become part of MGM) and Famous Players–Lasky (which became part of Paramount). By the 1930s, however, many fewer women could be found behind the camera. Dorothy Arzner was the most successful and one of the few women who directed studio films during the 1930s and 1940s, and Arzner’s distinctive voice was important. She created strong female roles for many top stars, including Lucille Ball, Clara Bow, Katharine Hepburn, and Rosalind Russell.

3. Film pioneer Alice Guy-Blaché directed more than one thousand films and was one of the first women to manage her own studio.

The star system

The studios also brought more stability to their business through branding and consistent storytelling. Over time, each studio developed its own distinct house style. MGM celebrated the glamour of its stars. “More stars than there are in heaven,” the studio’s publicity department boasted. Paramount was known for its European sex symbols like Marlene Dietrich, while Warner Bros. specialized in grittier films geared towards an urban working-class audience. Since many of the studios owned theater chains and dealt regularly with the same exhibitors, they also had detailed demographic information about their ticket buyers.

Nevertheless, every studio diversified its offerings in order to reach a range of theatergoers and weather changes in taste. In addition to its gangster films, for example, Warner Bros. adapted literary fare for John Barrymore. And Warner Bros. discovered a new market for musicals with Busby Berkeley’s depression-era hits like 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Footlight Parade (all 1933). Most studios also made a few prestige pictures every year, calculated to improve the studio’s reputation even if the films did not turn a profit. At the first Oscar ceremony in 1929, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognized both the commercial and artistic sides of studio output, giving top awards to both the best picture of the year and the most “unique and artistic” picture.

The studios’ most stable commodities were their stars. Stars had always had a place in the American movie business. Edison’s first films, we have already seen, featured vaudeville stars in the hope of bringing established audiences to the new medium. Later, the independents capitalized on well-known theater stars in their bid to draw middle-class patrons to the movies.

Stars promise repetition and consistency, counteracting the uncertainties of filmmaking. Over time, the studios developed a system for crafting and controlling star personas that would remain stable across films and keep moviegoers’ attention with publicity between new releases. The English-born Charles Chaplin played a series of different roles before discovering the Little Tramp character that he would play into the sound era. The Little Tramp wore the same hat, pants, and shoes from film to film, and he always exuded pathos and resilience as he failed at work but (often) triumphed in love.

Chaplin’s devotion to a single character was extreme, but it was only an amplification of the consistency offered by other stars. Humphrey Bogart played Bogie whether he was a club owner in North Africa or a Los Angeles private detective. Katharine Hepburn played Katharine Hepburn whether she was a Philadelphia socialite or a New York reporter.

It almost always took time to refine a star’s image. In his first films, for example, Cary Grant (born Archibald Leach in Bristol, England) did not play the suave, comic, well-dressed leading man that he would become. In his early film Blonde Venus (1932), with Marlene Dietrich, Grant has a sinister side, and in a series of Mae West films Grant played the innocent. It was not until The Awful Truth in 1937 that Grant found his debonair persona. Like most stars, Grant’s image was carefully crafted, and it remained coherent even as he worked in different genres and enjoyed ongoing collaborations with some of the most distinctive directors in Hollywood, including Alfred Hitchcock, George Cukor, and Howard Hawks.

Grant’s offscreen persona complemented the dapper demeanor and charmed life he led onscreen. Fan magazines reported on Grant’s glamorous nightlife and multiple marriages to costars and socialites. Stars’ high profile relationships would often develop into popular press soap operas on their own, part real, part studio publicity, and part public fantasy. When Grant married Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, for example, the press began to refer contemptuously to the made-for-publicity couple as “Cash and Cary.” It was a precursor to the later celebrity relationships worthy of their own names like Brangelina (Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie), Bennifer (Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez), and TomKat (Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes).

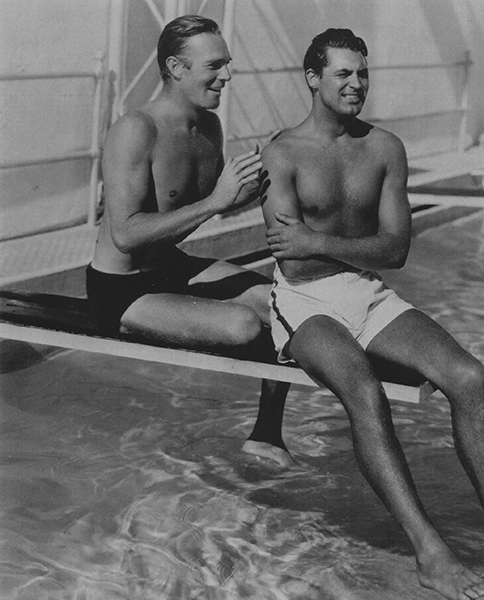

Reporting on stars’ personal lives often allowed for multiple and contradictory interpretations of their star persona. Photos of Grant exercising with his longtime roommate Randolph Scott, for example, could reinforce the image of them as playboys or stir speculation about Grant’s bisexuality. Either way, the carefully curated images brought in more devoted fans.

Whatever fans saw and read in newspapers they took with them into the next film. Studios carefully constructed star images, producing their own fan magazines, training stars for public appearances, and in many cases even orchestrating stars’ private lives. As a result, audiences could not help but watch movie stars with double vision, as both the part they played in a particular film and as the star persona that developed offscreen and across films. The studios counted on this dual vision to anchor the unpredictable successes and failures of individual films in the consistency of the star system.

4. Studio publicity departments used images that appealed to multiple publics. Photos of longtime roommates Cary Grant and Randolph Scott portrayed the active lifestyle of the two screen heartthrobs, but the images could also be interpreted as showing them as a couple.

There is no better evidence of the value of stars than the animated films of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Disney had Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, and Pluto, while Warner Bros. had Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Elmer Fudd. The star system became so important to making, marketing, and consuming movies that even animated movies needed stars to build audience loyalty and character recognition.

During the classical studio era, stars were closely associated with a studio’s house style as well, because stars were generally long-term studio employees. They were under contract to a single studio for five to seven years and worked forty weeks a year with twelve weeks of unpaid vacation. Even top-billed stars had very little say about the roles that they were assigned.

As production heads came up with a plan for the year’s slate of films, they chose projects around their stable of stars. And if a star was not needed, he or she could be loaned out to another studio, often at a very high price. In rare cases, top stars had one loan-out a year built into their contracts, so that they could pursue artistic ambitions. But lending out a star could help the home studio as well. When MGM loaned Clark Gable to Columbia Pictures to make Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934), Gable won an Oscar and came back to MGM more bankable than ever. The loan was also beneficial to Columbia, which had a top director, Capra, but a modest stable of actors.

In the 1930s, a few stars, including Fred Astaire, Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, and Ginger Rogers, were able to remain successful as freelancers, liberated from long studio contracts. But they were the exceptions. Stars, for the most part, were tied to an individual studio and remained an essential part of that studio’s identity.

As stars’ celebrity grew, so did their power in the studio system. In the mid-1910s, Chaplin and Mary Pickford were able to convert their audience draw into lucrative salaries and creative autonomy. Chaplin built his own studio, and Pickford shared in the profits from her films as early as 1915 (although many histories claim incorrectly that Jimmy Stewart was the first star to get profit-sharing “points” for his role in Winchester ’73 (1950). In 1919 Chaplin and Pickford teamed up with Douglas Fairbanks and director D. W. Griffith to start United Artists, which served as a distributor for independent production companies before becoming a full-fledged studio itself.

During the height of the constricting contact system in the 1930s, several of the most successful stars fought for more control over their own careers, including Bette Davis, Myrna Loy, and James Cagney, who all lost battles with their respective studios. It was Olivia de Havilland, frustrated with repetitive ingénue roles, who successfully took on the studios and won some rights for her peers, at great personal expense. In 1946, de Havilland thought she had completed her seven-year contract with Warner Bros. But the studio informed her that an additional six months had been added on to compensate for periods when she had turned down roles and not been actively working—a common studio practice. De Havilland sued the studio and won in California’s Supreme Court, which decided that her contract lasted for seven years regardless of whether she was shooting a film or not. It was an important victory, both legally and symbolically, demonstrating that actors could no longer be treated like the property of the studios. It also showed the strength of the Screen Actors Guild, the actors’ union incorporated in 1933, which supported de Havilland. The victory proved to be costly for de Havilland, however. In retribution the studios refused to hire her for two years.

The genre system

Stars bring consistency to filmmaking and filmgoing; genres bring order. Throughout the history of Hollywood, westerns, musicals, and other genres have been important to all aspects of film production, distribution, marketing, exhibition, and consumption. Genres breed familiarity by standardizing storytelling, offering formulas for defining characters, and controlling viewers’ expectations. Genres also provide a vocabulary for inserting political meaning into film—even a small change in a genre movie can have large repercussions for how the film is interpreted by audiences and critics.

Of course genres preceded movies. There are genres of painting, theater, literature, and music, many of which migrated to film. Yet it is difficult to articulate an adequate definition of genre or even to define a specific genre. Many different elements make up a genre, some or all of which can be present in a specific film. Settings, iconography, narrative patterns, and aesthetic styles are just some of the ingredients that make up a genre. Westerns can be identified by their prairie, ranch, or frontier-town locations. Zombies or vampires indicate that we are watching a horror movie. All that is needed to make a film a comedy is a light attitude or ironic tone. And films noirs are characterized by high-contrast lighting and femmes fatales characters, if indeed film noir is a genre and not an aesthetic style or historical period, as critics have debated. To make matters more complicated, a single film can mix genres, such as the longstanding comic-horror genre, which stretches from Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) to Young Frankenstein (1974) to Scary Movie 3 (2003).

During the classical studio period, the 1910s–1960s, genres were closely tied to both house styles and the star system, and it is impossible to determine which component of the studio system led the others. Warner Bros. specialized in gangster films in the 1930s, creating an identity for the studio. The genre appealed to the studio’s working-class urban audience and made use of its tough male stars such as James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and John Garfield.

In the 1930s, Universal Studios became known for a successful run of horror films, starting with Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), and The Old Dark House (1932). The Universal horror cycle adapted popular plays, and it employed the production design, lighting, and cinematography that German émigré filmmakers trained in the expressionist style brought with them to Hollywood. Universal horror became one of the best-known studio genre brands. Although genres became part of studios’ identities, no studio claimed exclusive rights to any one genre. Every studio made musicals and westerns, and when one studio had a breakaway hit with a genre film, the other studios invariably jumped in with their own follow-up film.

The star system, too, was deeply intertwined with the genre system. The early success of westerns in the 1900s was among the factors that drove production from New York City to Fort Lee, New Jersey, and eventually west to Los Angeles in search of rugged terrain and sunshine. Westerns also called for iconic heroes and villains, and many of the early male stars rose to prominence as distinctly western stars, including William S. Hart, Tom Mix, Roy Rogers, and Gene Autry. The iconicity of both the hero and the star overlapped perfectly and reinforced each other. Some stars became so closely identified with particular genres that they were typecast, unable to break out of their defined role. John Wayne made westerns. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers made musicals. Errol Flynn made costume dramas. Esther Williams was restricted almost entirely to aquatic ballet musicals.

Like stars, producers and directors became associated with genres, and the structure of the studios revolved around genre production. Units within studios were devoted entirely to making romantic comedies or westerns. Producer Val Lewton ran the horror unit at RKO. At Warner Bros., director William Dieterle specialized in biographical films (a genre later dubbed the biopic) starring Paul Muni, and MGM’s Freed Unit became famous for making some of the most successful musicals of the classical studio era.

Under the direction of lyricist-turned-producer Arthur Freed, the Freed Unit employed top songwriting teams, including Richard Rodgers–Lorenz Hart and Betty Comden–Adolph Green. At different times, the Freed Unit also included singing and dancing stars Gene Kelly, Lena Horne, Cyd Charisse, and Frank Sinatra.

The Freed Unit’s commercial and artistic success owed much to its novel approach to the musical genre. The problem that all musicals seek to overcome is how to incorporate music into everyday life in a way that audiences will find believable (or at least not laughable). Musicals frequently explain all the singing and dancing by using a backstage musical plot, the most common subgenre. Everyone is singing because they are putting on a show. In other musicals, there is a pause, music swells up on the soundtrack, and the characters burst into song. Freed aimed for a more integrated approach to music and dancing. First, Freed Unit musicals contain what Freed called a “thesis,” which explains why a character will break into song, and, second, the song is essential to the plot. The narrative does not come to a halt, making way for a musical number; the number advances the story.

Director Vincente Minnelli’s 1944 Freed Unit musical Meet Me in St. Louis, for example, contains a trolley car scene with a clear thesis. The film’s star, Judy Garland, boards a trolley as it clangs along and the conductor dings the bell. The vehicle is almost musical, and indeed the rhythm and noise of the trolley begin to mingle with music on the soundtrack. Garland starts to feel her love for a boy swell inside her, and she begins to explain in a half talking, half singing voice that she “went to lose a jolly hour on the trolley and lost [her] heart instead.” Then she states the thesis clearly:

Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

Ding, ding, ding went the bell

Zing, zing, zing went my heartstrings

From the moment I saw him I fell.

The musical sounds of the trolley mirror the rhythm of her heart. That metaphorical thesis is the springboard for a song, and the musical number is seamlessly integrated into the narrative and action of the scene.

The Freed Unit tweaked the musical formula, but providing storytelling formulas is the primary function of genres. Genres offer premade characters, settings, tensions, endings, and subplots. A producer can turn to a writer, as the fictional producer does in Barton Fink (1991), the Coen brothers’ movie about Hollywood history, and say, “We’re gonna put you to work on a wrestling picture.” And the writer (like the audience) should already know exactly what to expect from the movie. When the producer tells Barton Fink that the wrestling movie will star Wallace Beery, the brawny real-life star of such films as The Champ (1931), the writer should have all of the elements needed to construct the main character and plot. Indeed, the pleasure of watching movie stars and genre films is not discovering how the film will end. We already know that the hero will triumph (or die if it is a tragedy). The pleasure comes from watching the complications that defer the ending and alter the narrative formula we are familiar with.

Moreover, every tiny alteration to a heist plot or an alien-invasion film is an opportunity for a writer or director to stamp the film with his or her authorial mark and make a statement about society. The reuse of the same plots in genre films makes them into rituals, like fables and bedtime stories, that reflect the times in which they are told. And small changes to the expected formula speak volumes.

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), director John Ford self-consciously calls attention to many of the tropes of the western while simultaneously looking out to American culture of the early 1960s. It is a film with two heroes. One is Tom Doniphon, a tough rancher played by John Wayne. The other is a frail lawyer, Ransom Stoddard, played by Jimmy Stewart. The film plays out their competing approaches to bringing civilization to the wilderness of the American West. Stoddard supports democratic institutions: the press, the school, and the rule of law. Doniphon claims that only violence gets results. Doniphon clearly represents a fading approach to law and order in the west, while Stoddard points to the future.

In the end, the story and the film’s message culminate with a three-person shoot-out involving Doniphon, Stoddard, and the villain terrorizing the town, Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin). And—spoiler alert—both heroes are proven right. The villain Liberty Valance is shot. At first it appears that Stoddard has killed Valance in self-defense, and, based on that one act of bravery, Stoddard goes on to win a seat in the US Senate and bring law and order to the state. We learn in a flashback, however, that it was really Doniphon who shot Valance, while hiding in the shadows. Cold-blooded murder, not justified self-defense, led to Stoddard’s political rise. Violence, the film suggests, is the necessary foundation for the institutions of civilization. And we need our wild heroes just as much as we need our political leaders.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance sets up a classic western plot point: the shoot-out. By repeating the scene, Ford shows us how the staging of the shoot-out can lead to different interpretations of the film and society. Ford trains his audience to read the meaning of the smallest genre details. The film also contains not so oblique references to the civil rights movement and the Cold War, just in case audiences missed the film’s relevance to contemporary politics.

Genre films like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance serve an allegorical function, retelling stories in ways that reflect back on society. And the more successful genre films are the ones that connect with the fears and concerns of audiences. For that reason, genres generally appear in cycles. We often hear that westerns, musicals, or other genres have died out and lost their relevance, only to see them return in new cycles that reimagine the genres for a new time.

The 1990s, for example, saw independently made westerns with black (Posse, 1993), female (Ballad of Little Jo, 1993), and, later, gay (Brokeback Mountain, 2005) heroes, inserting greater diversity into American national mythology. Westerns, in particular, remain important, because they symbolize the always new social and political frontiers of American society. And genre films retain their power, because they turn filmgoing into a ritual. Audiences go to genre movies for a communal retelling of familiar narratives, reading for meaning in the details.