1. Neoliberalism takes over

Inequality was rising up the political agenda of many affluent countries before the financial crisis of 2008. Five years later, most of these countries were returning economic data which showed the worst of the recession was over.1 With growth and prosperity slowly returning, inequality was a pressing issue once more, described by Barak Obama in this way:

Since 1979, when I graduated from high school, our productivity is up by more than 90 percent, but the income of the typical family has increased by less than eight percent. Since 1979, our economy has more than doubled in size, but most of that growth has flowed to a fortunate few … The top 10 percent no longer takes in one-third of our income – it now takes half. Whereas in the past, the average CEO made about 20 to 30 times the income of the average worker, today’s CEO now makes 273 times more. And meanwhile, a family in the top 1 percent has a net worth 288 times higher than the typical family, which is a record for this country. (Obama 2013: n.p.)

The president emphasized that these trends were worse in the USA but had nevertheless affected almost all the rich countries of the world.

The largest study of inequality so far undertaken suggested that the more equal world Obama remembered in the 1970s was something of an anomaly (Piketty 2014). Most incomes did not come from investing in capital but incomes from capital tended to grow much more quickly than incomes from wages or state benefits. Capitalism naturally concentrated the ownership of capital (which generated further wealth) in fewer and fewer hands. Even if capital was destroyed by wars and depressions, states had to take extraordinary measures in order to avoid concentrations of income and wealth. From the 1970s, most rich countries ceased to take effective counter-measures and inequality returned to historic levels and then kept on growing. Further impetus was given to the growth of inequality because, over this same period, more powerful employees (like the CEOs mentioned by Obama) got away with paying themselves larger incomes which, in turn, gave them access to capital.

Why should country after country have apparently lost the will to control the concentration of wealth and prevent higher-earners taking home ever-higher incomes? President Obama blamed the kind of politics that had taken hold in the United States since the 1970s, for example the unpopularity of taxation for the rich, and of public-spending which was of most benefit to the poor. He also identified the loss of power amongst lower-earners with the weakening of trade unions, and equated the bulging portfolios of the CEOs and other high-earners with the loss of community. At the end of the twentieth century, the decline in community had actually been a bigger concern in the USA than rising inequality. There was over-whelming evidence that people were much less likely to take part in collective endeavours in their neighbourhoods, cities and workplaces (e.g. Putnam 2004). Declining membership of civil society associations might be related to the growing gap between rich and poor (Skocpol 2004; Wuthnow 2004), but the link between inequality and declining collectivism is easiest to demonstrate using data on trade union membership.2

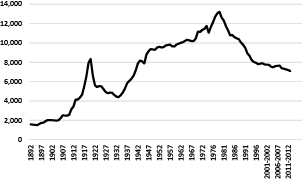

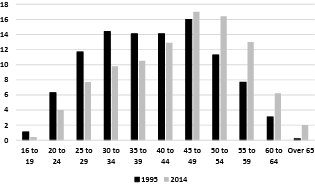

As Obama pointed out, the USA was far from the only country to have seen steeply rising inequality. The United Kingdom consistently appeared, along with the USA, amongst the four or five rich countries with the most extreme inequality (OECD 2014). Trade union membership in the UK topped out at 13 million in the late 1970s and then fell apace in the 1980s. From the mid-1990s, it settled down at under 8 million (Figure 1.1). People were more likely to be in a union if they were older but membership declined for all ages after 1999 (Figure 1.2).

Sources: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (2015a: 20), drawing on Department for Employment (1892–1973) and Certification Office (1974–2012).

Figure 1.1 UK trade union membership since 1892 (thousands of members)

Source: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (2015b: table A103) drawing on the Labour Force survey.

Figure 1.2 Age of trade union members, 1995 and 2014 (percentages)

Several reasons were offered to explain this decline. The legal status of trade unions was weakened by successive Conservative governments and strategic industrial disputes engineered by employers, often with government connivance (Bagguley 2013; Fevre 1989). Other possible causes included structural changes in employment and, although this is highly unlikely,3 changes in the gender mix of various occupations (Rosenfeld 2014; Willman et al. 2007).

Whatever the reasons behind it, the trend in UK union membership confirmed that inequality increased as collectivism declined from the 1980s. There were straightforward reasons to think these trends were connected. For example, in the UK in the 1960s and 1970s the main purpose of trade unions seemed to be to use any evidence of widening pay inequality to leverage pay claims and therefore ratchet up wages so that their members kept pace with the richest employees. This ratchet acted as a natural adjustment to any sign of increased inequality and, at a time of high inflation, it also meant most employees thought of union membership as a necessity. If collectivism declined from the end of the 1970s, and depressed union membership, the weakening of catch-up pay claims would provide at least one clear reason to expect inequality to grow.

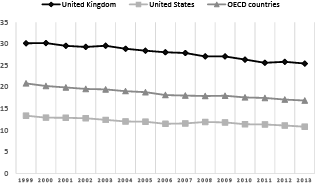

Similar changes may well have occurred elsewhere because the proportion of employees in trade unions fell across all the richer countries from 1999 (Figure 1.3). This international proof of weakened collectivism was a good fit with generally increasing inequality (Streeck 2014). On the other hand, countries with similar experiences of rising inequality still had very different trade union densities. Of course, there could be other contributory causes, but if declining collectivism was the major contributor to rising inequality we might have expected to see UK union density, for example, well below the OECD average instead of well above it. If it was the absence of collectivism that placed the UK with the USA amongst the most unequal rich countries, we would be hard put to explain why 25 per cent of UK employees remained in trade unions whereas only 11 per cent of US employees did so. Perhaps there was something else that these societies had in common that would serve as an explanation for their common inequality?

Source: Data extracted 18 December 2015 from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=UN_DEN#.

Figure 1.3 OECD trade union density, selected countries 1999–2013 (percentages)

President Obama was taking a risk by making inequality the focus of his second term of office but he would have been taking a far greater risk if he had blamed it on individualism – the idea that society ought to give each of its members the chance to make of themselves what they will. In a society which values individualism, the way that people’s lives turn out is not determined by the accidents of their birth. What work they do, who they will marry (if they marry at all), which if any God they worship and how they will spend their leisure is not pre-determined by society’s expectations of them. On the other hand, people are expected to know their own minds, and be able to make plans, and take decisions, which help them to achieve personal objectives.4 There is no requirement for these objectives to be different from other people’s goals however. Individualism and conformity are not enemies and individualism need not imply individuality. It requires only that people follow their dreams even if those dreams are the same as everyone else’s.

Approval of the idea that individuals must be given every chance to make their own lives was so fundamental to Americans’ self-image, so much a part of the political consensus, that to blame it for inequality would have immediately lost Obama most of the potential support he wished to build for action against inequality. All the same, it would have been easy to make a connection between individualism and inequality since a society which gave individuals their heads might find that some used their freedom to increase their incomes and wealth while others failed (Spicker 2013). Individualism would also explain the unpopularity of taxation for the rich because high taxes could be seen as a limitation on individual freedom. Over the long term, a society which was committed to individualism would become more and more unequal.

Another politician, this time from the UK, explained some of this in the week before the president’s remarks quoted at the start of this chapter. The Mayor of London’s metaphor for a society shaped by people who realized they were in charge of their own fates was a cereal box which was being vigorously shaken by an invisible hand:

The harder you shake the pack, the easier it will be for some cornflakes to get to the top. And for one reason or another – boardroom greed or, as I am assured, the natural and God-given talent of boardroom inhabitants – the income gap between the top cornflakes and the bottom cornflakes is getting wider than ever. (Johnson, 2013: n.p.)

Since the UK and the USA were consistently seen as the most individualistic of countries (Hofstede 2001; Macfarlane 1978; Tocqueville [1840]2003), this might explain why they both had so much inequality; but surely less collectivism and more individualism are different sides of the same coin (Dorling 2011; Gans 1988; Gilbert 2013)?

On this view, when more and more of us realize that what we do for ourselves can have much more effect on our health, wealth and happiness than any joint ventures, we increasingly shape the world so that those efforts pay off. In this way, increased individualism affects the climate for public policy. It makes us less favourable towards progressive taxation, collective agreements over jobs and pay, public spending and oversight over high-earners’ pay rises. As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, this amounts to releasing the brakes on capitalism’s tendency to increase inequality. In sum, if we strive harder on our own behalf, and those efforts are more likely to pay off, there will be less collectivism and more inequality.

In this case, individualism cannot explain why inequality levels in the USA and the UK were so similar even though they had such different levels of unionization. If the UK had more people in trade unions, it must, therefore, have had less individualism. This forces us to consider whether there are different types of individualism and whether the inverse relationship between collectivism and individualism is as straightforward as is usually assumed (Lukes 1973). This book argues that the UK was for some time more committed to collectivism (including unions and high taxes) than the USA, but was nevertheless also committed to individualism (also see Spicker 2013). The USA was the laboratory for the development of a strain of individualism which was more hostile to collectivism, and the nature of individualism in the UK eventually changed under the influence of this American strain.

The Mayor of London’s remarks were made as part of the annual Margaret Thatcher lecture, commemorating the British Prime Minister most closely associated with the conversion of Britons to a more American individualism. They were persuaded to vote for her Conservative party in sufficient numbers to provide her with the mandate to wrestle with Britain’s collectivist institutions. They did not see a need for trade unions in their own workplaces and saw wresting power from the trade unions as good reason for voting for the Conservatives (see Chapter 11). Other reasons for voting Conservative included disquiet over high levels of taxation and public spending, particularly on welfare (Clery et al. 2013; Gilbert 2013).

The fact that the UK retains a higher rate of unionization than many other countries suggests that American individualism has not yet fully replaced the older, British individualism. The same might also apply to the differences in the health of civil society in the two countries, which suggest that other types of collectivism have also been more persistent in the UK (Grenier and Wright 2006; Hall 1999, 2002). All of this tells us that, without the conversion of enough British voters to American individualism, progress would have been much more difficult, perhaps impossible, for the neoliberal bandwagon which Thatcher helped to get on the road.5 The older British individualism not only found the rampant inequality that accompanied neoliberalism morally repugnant but also played a key role in shifting power and resources from capital to labour over many decades (Streeck 2014). The political defeat signalled by the election of the first Thatcher government helped capital to win back the lost power and treasure and, as it did so, inequality increased.

Despite all of this apparent concentration on the USA and the UK, this book also has something to say about the future of work and politics in other countries. This claim rests on the knowledge that all politics, and all possible ways of organizing work, will have to reckon with one type of individualism or another for the foreseeable future. There seems to be little doubt that many other countries will follow the USA and the UK in completing the transition to the kind of individualism which is wholly compatible with neoliberalism and burgeoning inequality (Streeck 2014). Understanding more about the way in which American and British individualism first diverged, and then converged, will help us to think sensibly about the future of European countries with long histories of social solidarity and former communist countries able to claim none of the individualistic heritage of the USA and the UK (Dardot and Laval 2014; Harvey 2005). In the last two countries, the issue is simple enough for anyone unhappy with inequality: how do they get off the neoliberal train? For Americans and Britons, it would be helpful to understand why they got on the train in the first place and what keeps most people in their seats, even though they may feel the train is no longer headed for a place they want to go to.

MORAL INDIVIDUALISM

Several chapters of this book will be spent explaining the divergence between American and British individualisms in the nineteenth century, but there was an earlier time in which many people in both countries were galvanized by the ideas of individualism propounded by one man, Thomas Paine. Paine, who migrated from Britain to America, was an important actor in the process which extended individualism from elites to the mass of the population or, at least, the male population. This process had in fact begun three centuries before with the Protestant Reformation and continued with the rising prosperity which was necessary to explain the need for, and attraction of, individualism (Hofstede 2001; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Norris and Inglehart 2009). Elites could get richer without any increase in the majority’s appetite for individualism but, with more general prosperity in prospect, men and women could begin to dream of autonomy and self-development, not just for themselves but for all (Spicker 2013). At the end of the eighteenth century, the fault lines between a new mass individualism, which assumed future prosperity for all, and an older elite individualism were visible in their different views of self-interest and charitable giving.

Edmund Burke – once Paine’s friend and subsequently his greatest opponent – spoke for the elite individualism which was anchored in a religion holding out against the wilder repercussions of the Reformation. Burke was an Anglican with Catholic leanings and his individualism was centred on the human quality of self-interest supported by religious belief: it was God who had placed self-interest in human hearts (Tawney 1926). The example of charitable giving helps to explain the contrast between this elite individualism and the mass individualism of Paine, in which religious belief was of little account. In eighteenth-century Britain, following God’s plan meant, for the most part, pursing self-interest and thereby promoting general prosperity. It was rare when something more than self-interest was required of the British elites and these were occasions for philanthropy. In 1774 Edmund Burke explained that charity was a Christian duty, on a level with settling our debts (though more enjoyable), but we had some choice in regard to when and how we met those obligations. This element of choice definitely added to our satisfaction but it was doing our duty that was the main source of our enjoyment because this earned us ‘divine favour’. In other words, philanthropy was mostly self-interest with a small admixture of choice (Burke [1774]1999).

Paine’s view of our duties to our fellows was very different. If individualism was for everyone, this required equality of opportunity and that, in turn, meant collective action. His commitment to mass individualism arose from a moral conviction that extending individualism beyond the elites would make for a better world, and not simply a richer one. In The Rights of Man ([1792]2014), Paine saw God as the source of both the equality of men and of their equal natural rights ‘which appertain to man in right of his existence’ (Paine [1792]2014: 198). God was also the source of our duty to treat our neighbours as we expect them to treat us. But, at least so far as political principles were concerned, Paine took the Deist view that God set the world in motion, with natural rights as part of the mechanism, and then sat on his hands.

From this point, Paine thought it was up to men, and sometimes women (Botting 2014), to make those rights a reality. This had been the point of not only the French and American Revolutions of the eighteenth century but also the (British) Glorious Revolution of the seventeenth. Political change was required to enact all the natural rights: ‘intellectual rights, or rights of the mind, and also all those rights of acting as an individual for his own comfort and happiness, which are not injurious to the natural rights of others’ (Paine [1792]2014: 198). From Paine we can look forward to the extension of democracy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including women’s suffrage, the abolition of the slave trade and slavery itself, the civil rights movement and anti-discrimination legislation. All of these struggles were intended to enact natural rights for those who had not yet had the opportunity to determine their own fates (Lukes 1973; Spicker 2013).

The contrast with Burke’s self-interested philanthropy is obvious. In Burke’s view, God had not left us to our own devices and guided us to carry on with both our self-interest and our occasional charitable giving to curry divine favour. Paine thought that the moral condition of a nation would be measured by its progress in enacting natural rights but he argued that this process required that individuals must also become more moral. In contrast to most eighteenth-century women and men, Paine thought there were many unfortunates who lacked the moral training which would show them how to act to advance their own health, wealth and happiness, while at the same time respecting the rights of others. Even if their natural rights were enacted, these people could not help themselves and would remain both wretched and poor:

Why is it that scarcely any are executed but the poor? The fact is a proof, among other things, of a wretchedness in their condition. Bred up without morals, and cast upon the world without a prospect, they are the exposed sacrifice of vice and legal barbarity … It is to my advantage that I have served an apprenticeship to life. I know the value of moral instruction, and I have seen the danger of the contrary. (Paine [1792]2014: 316)

Paine thought that government should spend the money it currently wasted on supporting the poor (and on ‘legal barbarity’) on a comprehensive scheme to provide general moral education. He also recommended several other innovations, including rudimentary welfare benefits and pensions which anticipated the welfare state, in the cause of putting everyone in the position where they would be able to make sensible efforts to advance their own health, wealth and happiness.

For Paine, enacting the principle of equal natural rights meant getting rid of priests as well as despots, and all established religion (including Burke’s) got in the way of the new morality that was so desperately needed by nations and individuals. All religions eventually lose ‘their native mildness, and become morose and intolerant’ (Paine [1792]2014: 214) and must make way for individualism which was the perfect substitute for religion as a source of the morality of nations and individuals. If the pious sought their principles and policies in the interpretation of God’s will, the principles and policies of individualism originated in the interpretation and enactment of natural rights. Of course, these natural rights still required men and women to believe in something, just as they might once have believed that the will of God was enshrined in the principles of religion. What was required now, however, was not a belief in supernatural intentions but a belief that every individual shared a common humanity which compelled others to recognize those natural rights. In this respect, humanity had replaced God as the first cause of the belief system from which morality could be developed (Fevre 2000a).

A century later, the French sociologist Emile Durkheim reached the conclusion that the replacement of conventional religion by a religion of individualism had become general (Cladis 1992a, 1992b). It is worth quoting him at some length because his words convey how much of religion’s mystique carries over into individualism. In an essay defending the campaigning role of intellectuals like himself in the Dreyfus case, Durkheim explained why any person could expect their natural rights to be treated as sacred by their fellows:

If he has the right to this religious respect, it is because he has in him something of humanity. It is humanity that is sacred and worthy of respect. And this is not his exclusive possession. It is distributed among all his fellows, and in consequence he cannot take it as a goal for his conduct without being obliged to go beyond himself and turn towards others. The cult of which he is at once both object and follower does not address itself to the particular being that constitutes himself and carries his name, but to the human person, wherever it is to be found, and in whatever form it is incarnated. Impersonal and anonymous, such an end soars far above all particular consciences and can thus serve as a rallying-point for them … In short, individualism thus understood is the glorification not of the self, but of the individual in general. Its motive force is not egoism but sympathy for all that is human, a wider pity for all sufferings, for all human miseries, a more ardent desire to combat and alleviate them, a greater thirst for justice. Is this not the way to achieve a community of all men of good will? (Durkheim [1898]1969: 23–4)

The relationship between the religious mystique of this individualism and the moral obligation that it placed on its followers to extend its benefits to all humanity will be explored in later chapters. For the moment, we need only to recognize that the individualism of The Rights of Man underpinned the reforming social movements of the nineteenth century, including those which most eloquently demonstrated the idea of a social conscience and the importance of emotion to the popularity and success of these ventures in collectivism (Flam and King 2005; Goodwin et al. 2001; Nussbaum 2013).

This is not to argue, however, that all of these necessary conditions for the development of this individualism originated in the nineteenth century and we have to remember that not everyone saw moral individualism as an alternative to religion. I noted the significance of the Reformation a little earlier, and it was through Protestantism (but not Burke’s Anglo-Catholicism) that individualism reformed Christianity. In the nineteenth century, evangelical Protestantism produced its own version of moral individualism for the masses but the ‘sacralization’ of the person – on which the elaboration of human rights has depended – has a very long history. Within this history, Christian thinkers and their secular opponents argued over the meaning of common Judeo-Christian traditions (Joas 2013; Siedentop 2014).

As the nineteenth century advanced, the general loss of religious belief meant that the social movements which pursued equality were increasingly dependent on Paine’s kind of moral individualism rather than on its religious counterpart. We will call it sentimental individualism. Durkheim often referred to moral feelings as sentiments, and for the author of this book ‘sentimental morality’ is always derived from beliefs about the qualities of human beings rather than religious beliefs (Fevre 2000a). As we have seen, Paine’s sentimental individualism entailed moral convictions. He believed that it was making our own moral decisions that made us autonomous moral beings. Since we live in a time when self-interest is thought to be best served by limitless choice, it is perhaps hard to grasp the connection being made between morality and choice in sentimental individualism.

One way of grasping the connection is to remember that in pre-modern times people had no choice but to fulfil the roles they had been assigned to. They did their duty as king or farmer or miller and this was how they acted morally. When morality is no longer defined by roles, we are speaking of moral individualism in which the choices we make are not defined by roles and yet allow others to judge how moral we are (MacIntyre 1966). This was why Paine contended that moral education was needed to make sure people were equipped to make their choices in a moral way.6 Simply giving them choices and trusting to self-interest were the cause of vice and degradation and their subsequent punishment.

By the mid-nineteenth century, God had entirely disappeared from John Stuart Mill’s statement of sentimental individualism in On Liberty:

We followed not God’s plan but our own framing the plan of our life to suit our own character; of doing as we like, subject to such consequences as may follow: without impediment from our fellow-creatures, so long as what we do does not harm them, even though they should think our conduct foolish, perverse, or wrong. (Mill [1859]2015: 612)

In other words, we must not take away their capacity to be autonomous moral beings. Choice had been directly substituted for self-interest as the source of our morality. It was a very different thing to go in for philanthropy when ‘framing the plan of our life to suit our own character’ as opposed to ascertaining we have God’s favour (Spicker 2013). Mill’s book on Utilitarianism (1863) explored some of the implications of the change, including the idea that, with the progress of civilization, our plans would be dominated by the idea of serving others. The ability to show ourselves moral by choice would lead us to make the most determinedly altruistic choices. There was a real danger that our social consciences would be over-developed but, in any event, the story of civilization entailed self-interest diminishing, then vanishing, in society’s rear-view mirror (Thilly 1923).7

All of this suggests we should not be surprised that individualism and collectivism, indeed individualism and socialism, could comfortably co-exist for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Cladis 1992a, 1992b; Gagnier 2010; Lukes 1969, 1973; Spicker 2013; Thilly 1923). Arguably the most important twentieth-century product of sentimental individualism was feminism, and the women’s movement offered a paradigm for the co-determination of social change by individualism and collectivism right up to the 1970s. Yet self-interest reappeared once more in the secular individualism of nineteenth-century liberalism and, eventually, neoliberalism. We know that when it did so the significance of choice in individualism was radically revised. While many were still able to see philanthropy as a moral choice, many more were preoccupied by the idea that choice was their highway to the satisfaction of whatever wishes and desires they might have. If self-interest was back in charge, where was the reward in philanthropy if there was no God who could show his favour to the philanthropist?

If we are going to explain why neoliberal individualism is responsible for generating and justifying inequality, we must understand why moral individualism apparently fell so far out of favour. Ultimately, this means understanding why people ceased to believe that every individual possessed qualities that required everyone else to recognize their natural rights. During the twentieth century, this belief in human qualities was gradually replaced by knowledge of human qualities, which stimulated the growth of the neoliberal incarnation of individualism. Chief amongst this knowledge was the certainty that all humans were motivated by self-interest.

Some commentators on individualism have argued that the recognition of the self-interest of the individual was present at its inception.8 It might be easy for us to take the same view, influenced as we are by the neoliberal version of individualism. This is why it has been necessary to explore the way in which the knowledge of self-interest was kept at arm’s length in moral individualism, but we must also spend a little time exploring neoliberal individualism itself. This will also provide an opportunity to explore those writers who argued that the transfer of allegiance from moral to neoliberal individualism made almost all of us worse off because it entailed a Faustian bargain which was hidden from us until long after the deal was sealed.

NEOLIBERAL INDIVIDUALISM

Understanding that neoliberal individualism justifies inequality is straightforward. Since it is founded on the knowledge that everyone who lives in neoliberal society is free to determine their fate, economic success or failure is the responsibility of individuals alone (Boltanski and Chiapello [1999]2005; Dardot and Laval 2014; Honneth 2012). Unlike the societies which Tom Paine was taking to task, all neoliberal societies incorporate the knowledge that the best has been done to ensure (for example, through universal public education and anti-discrimination legislation) that every one of these individuals is in a position to benefit from this freedom (Brown 2015). The poor and indigent can no longer be excused by their lack of moral education in the way that Paine had argued. If their morality is in question, this is the fault of the earlier insistence of the state (in line with Paine’s original plan) on providing welfare which made them unfit to take advantage of the myriad opportunities for self-determination provided for them (Somers and Block 2005). Less state interference in their lives will ensure that they fully appreciate the opportunities they have and the responsibility they bear. The proper welfare policies to facilitate individualism are those which make sure work is always more of an attractive alternative than state hand-outs (Dardot and Laval 2014; Spicker 2013). So, inequality is justified, but a wider point applies well beyond those in the bottom 10 per cent of income distribution.

Critics of neoliberalism argue that, for most people in neoliberal societies, individualism now condemns them to less and less freedom, even as common knowledge declares it self-evident that their fates are in their own hands (Boltanski and Chiapello [1999]2005). Most of the writing which argues this point draws on European social theory and social and political philosophy (Bowring 2015). In particular, it draws on French philosopher Michel Foucault (Brown 2015; Dardot and Laval 2014) and German Critical Theory.9 Yet, it is the recent history of Britain that provides a disproportionate share of the examples given to explain the idea that neoliberal individualism delivers less freedom than it promises. It is often implied that Britain pioneered many of its key features, including the extension of neoliberal individualism to the public sector with ‘new public management’ (Streeck 2014). The emphasis on the British experience arose from the way European theorists could see in it the starkest, and earliest, example of a society jumping the European tracks to join the USA in a dash towards a neoliberal future. There was also the fascination with the personality of Margaret Thatcher, sometimes portrayed as the author of neoliberal individualism and responsible for the ‘clearest formulation of neoliberal rationality’.10

In all of this writing, neoliberal individualism is portrayed as making impossible demands on people that diminish their wellbeing and even make them ill. By agreeing that neoliberal rationality describes how the world works, and making its knowledge our own, we commit to much more than keeping our résumés up to date (Rose 1999). Whereas in the early nineteenth century individualism was just a matter of self-determination, later in that century some elite members began to explore the additional opportunities that the advent of Romanticism had created for self-realization.11 By the (later) 1960s and 1970s, such opportunities had become more general and people could apparently use their freedoms not only to act as autonomous human beings determining their own futures but to express themselves and, through experimentation, discover wishes and desires that they might use their autonomy to pursue (cf. Bowring 2015).

This development was most obvious in the sphere of consumption (Streeck 2014), but self-realization was also insinuated in the process by which people determined their own fates by selling their services on the market. The presentation of wishes and desires became an indispensable part of the marketing of individuals who began to act as entrepreneurs on their own behalf, focusing all their capacities and emotional resources on getting a job or succeeding at work. The self that the nineteenth-century Romantics were seeking turned out to have identical interests to employers. The innovation of self-government through entrepreneurship can be traced back to the 1940s but, once fully developed, it meant that all employees who were free to govern themselves must be ready to take advantage of any new opportunities they had to make more from exchanging their services. At the same time, their motivations had to match whatever the opportunity (whether a new project or an entirely new job) might require. They must be prepared to embrace enthusiastically every change in their work and market position as the product of their own choices. In this way, their own wishes and preferences were revealed as identical with those who authored the changes, usually their employers.

Managers could not escape the Faustian bargain of neoliberal individualism, indeed they might put more of themselves at stake, but the services they provided to their employer supplied the technology required to enforce the bargain. This might be most obvious in the writings of Peter Drucker, the American management writer (born in Austria) who gave us the term ‘management by objectives’, or in the British experience of new public management which Drucker influenced, but numerous empirical studies showed the techniques management used to force people to behave like entrepreneurs (Fevre 2003). This meant discontinuing any remaining collective objectives or rewards and making all objectives and rewards effective at the level of individual employees. The employment relation was entirely reduced to that between the employer and the individual, with quantitative data apparently underpinning robust and objective knowledge of the individual’s contribution.

The supposedly objective judgement of individual employees was meant to derive in some way from assessment of the degree to which the needs of the client or customer had been met rather than against criteria derived from the organization’s hierarchy or procedures. In this way, every employee, not simply those with managerial responsibilities, was placed under direct market pressure. All of these techniques were geared to ensuring that employees were continually reminded that they were in competition with each other (Streeck 2014). One aspect of the Faustian bargain is revealed: an individual’s autonomy at work could only be used to put them in a position where they were required to use greater and greater self-control. In typical Foucauldian fashion, the managerial technology meant individuals only did well if they submitted to disciplining themselves and learning to live with the increasing demands they were obliged to heap on their own heads (Brown 2015; cf. Bowring 2015).

There is a large English-language empirical literature on these management innovations (see Chapter 9), but the theoretical literature on neoliberal individualism draws mainly on the French management and work literature (Coutrot 1998; Le Goff 1999, 2003). Similarly, although there is a great deal of American and British empirical sociology on the way workers suffer from the demand to counterfeit authenticity, the theorists all made use of the work of French sociologist Ehrenberg (2009) on the rise of depression (as measured both by presentations of symptoms and the consumption of medication). Ehrenberg ascribed this phenomenon to employees’ permanent state of anxiety about their performance, not simply their fear of losing their jobs but an existential insecurity about themselves and their capacities which floated free from any specific fear of loss on income. They were in fact made ill by their experience of the gap between the promise and the reality of neoliberal individualism.

While not always as specific as self-blame, the gap was filled with a type of introspection that ushered employees onto a slide into depression. Indeed, depression might begin when individuals were told to make the plan of their lives out of the resources they found inside themselves (Ehrenberg 2009). Self-realization now appeared to be a curse which insisted on constant self-examination which damaged people. Later in the book, we will explore the idea that those who were most at risk of this damage were those employees who had not yet abandoned the idea that their choices made them autonomous moral individuals. They therefore retained an expectation of recognition whereas their organizations had no memory of their mutual history and cared only for the entrepreneurial employee and the demands of the project in hand.

Though writers of social theory disagreed on how much was intended and how much was a sort of happy accident (for capitalism that is), for all of them neoliberal individualism represented a way of getting more out of employees. For some, the benefits for capital lay in the delayering of management, the refinement of flexibility and the facilitation of ‘network capitalism’ that self-governing neoliberal individuals offered. We should not, however, under-estimate the more straightforward benefits of work intensification (see Chapter 14). These benefits depended on reducing employees’ commitment to trade unions and collective bargaining and on a straightforward shift in the balance of power between capital and labour (Perelman 2005; Streeck 2014). Getting employees to abandon collectivism meant persuading them of something that was far from straightforward: that a new, American kind of individualism was in their interests and that neoliberal capitalism was the guarantor of that individualism.

The journey from the individualism of the early nineteenth century to its neoliberal version involved transforming the capitalist enterprise’s supreme indifference to the self-determination (and still more, the self-realization) of its employees to such a degree that the enterprise, along with the market, would seem to be individualism’s natural home. Employees had to be persuaded that the success of enterprises depended on the thoroughness of their adherence to the principles of individualism. They had to believe, in the hackneyed phrase of their managers, that this was a ‘win-win situation’ in which it was the individualism that really was in their employees’ interests that would best serve capitalism. So successful was this approach that 4 out of 5 employees became convinced that they were treated as individuals in their workplaces (see Chapter 10). In fact, neoliberalism portrayed the enterprise and the market as the only legitimate arena for individualism to flourish. All of this persuasion required a heroic effort from ‘administrative elites, management experts, economists, pliant journalists and political leaders … in virtually every country’ (Dardot and Laval 2014: 229), but also ‘human resources departments, recruitment agencies and training experts’. Responsibility even extended into academics and ‘well-intentioned reformers, who believed that a secure, flourishing worker was a more motivated, and therefore more efficient, worker’ (Dardot and Laval 2014: 286).

PROSPECT

This rarely, if ever, features in the writing we have been discussing, but the success of a mission to persuade employees that the individualism they crave could only be found in the market and the workplace goes some way towards explaining why so many employees of relatively modest means showed their support for neoliberal politics at the ballot box. This success is not a sufficient explanation for burgeoning inequality, however. The opening chapters of this book show how sentimental individualism did much to stimulate reform in the nineteenth century because the status quo was so far from that in which people could put any trust in their own actions to prosper (Meyer 1987: 250). When so many had so little control over their own fates, this kind of individualism was utopian and, for that reason, it moved millions to activism and to demands for reform. Yet, when utopia failed to arrive for decade after decade, the conditions needed for popular support for sentimental individualism began to dissolve. The evident disenchantment with sentimental individualism came to the fore long after the structural changes that it demanded had been completed. For example, the complaints of too much trade union power, or a burgeoning culture of poverty, became a popular chorus only at the point that changes in social policy, education, economic policy and employment relations appeared to have failed (Streeck 2014). By this I mean that they had not levelled the playing field for individualism in the way Tom Paine had anticipated when he planned to put an end to ‘wretchedness’ (Somers and Block 2005).

The dissolution of the elements that had succoured sentimental individualism involved not only disappointment and disillusion with failure but also the concrete achievements that individualism wrought in the architecture of the richest nations. Neoliberal societies did more than simply incorporate the knowledge that the best had been done to ensure (for example, with universal public education and anti-discrimination legislation) that every individual was now in a position to benefit from the freedom to determine their own fate. For example, individuals’ access to universal education and their acquaintance with modern employment relations systems made them open to the idea that everyone, including their employers, could benefit from a self-interested individualism. In other words, the concrete achievements of sentimental individualism helped to put in place the necessary conditions for the reappearance of an individualism that could be equated with self-interest.

Almost all of the writers referenced in the previous section saw the triumph of neoliberal individualism as neither a conspiracy nor a reflection of the logic of capital. It was not the result of a well-worked plan but was tentative, contingent and gradual. At times, developments in very different spheres (sociological, philosophical and economic, for example) came together in an uncoordinated way that might be described, after Max Weber, as ‘an elective affinity’ (Honneth, 2012). I share this reluctance to read co-ordination and strategy into history. I prefer to see neoliberal individualism as the consequence of the failure of promised utopia to arrive and changes within capitalism and individualism which produced an apparent symbiosis in neoliberal individualism.

If history and contingency are inescapable, I ought to be very reluctant to make predictions but, nevertheless, this book can tell us something important about the future of work and politics. As Marx might have said, neoliberalism contains the seeds of its own transformation, and this is especially true of work. Later chapters suggest that the experience of employment provides a daily test of the fidelity of neoliberal individualism which it frequently fails. At the end of the book, I consider the possibility that awareness of this failure might re-establish sentimental individualism in a way that re-activates the perceived need for collective action and reinvigorates the politics of inequality. Inviting people to think of themselves as individuals while at work turned out to be a trap for employees in the medium term but perhaps, in the longer term, the invitation might rebound on capitalism? Making employees think they can make a difference at work is presently the key to their self-control, but what if they refused to give up on the promise they thought they had been made? If people refuse to abandon the hope that they are individuals, rather than undifferentiated labour power, individualism might once again offer a utopian ideal which cannot condone inequality and stimulates criticism and reform (Spicker 2013).