13. The hidden injuries of cognitive individualism

Chapter 1 mentioned research linking neoliberalism and depression, for example arguing that people’s mental health suffered when they were made entirely responsible for their own fate. Neoliberal individualism, it was suggested, subjected people to chronic insecurity, not simply because they might lose their jobs but because they never knew whether they were doing well enough in them. More recently, Paul Verhaeghe (2014), a Belgian professor of clinical psychology and psychoanalysis, claimed that neoliberalism caused not only depression but also self-harm, eating disorders and personality disorders.

According to Verhaeghe, all of these illnesses could be caused by the ersatz moralities described in previous chapters of this book, especially the attachment of moral meanings to success and failure in the labour market and workplace. Within the workplace, performance was ascertained through intrusive systems of monitoring, measurement and comparison, which increased our anxieties and made us fearful of other people, both as judges of our performance and as our competitors. One consequence of this fear was an increase in workplace bullying as workers vented their frustrations on those in the workplace who were unable to stand up for themselves.1 This was an example of a more general increase in childish behaviour as people became dependent on arbitrary, shifting and often trivial signs of their worth. As a classic American sociological study would have put it, they were ‘other-directed’ and unable to rely on their own moral sense (Riesman 1950).

The idea that neoliberalism involved a loss of personal autonomy was at the centre of Verhaeghe’s account, just as it is a major concern of this book. He argued that the promise of individualism was often deceptive, falsely claiming to offer freedoms that we could only blame ourselves for not grasping. He took much success and failure in the neoliberal economy to be beyond the control of the individuals involved, but argued that they generally did not realize how little control they had and so habitually attributed their success and failure to their own actions. This was especially corrosive of the mental health of those who blamed themselves for their lack of success. These are persuasive ideas but they are of limited use in helping us to understand the current situation without the right kind of data.

Even the notion that mental illness has increased is not securely anchored in empirical evidence. Chapter 1 noted that Alain Ehrenberg’s thesis about mental illness and neoliberalism took the increased presentation of symptoms, and levels of medication, as evidence of rising rates of depression (Ehrenberg 2009). Both trends might actually be the result of a higher public profile for mental illness, together with reduced stigma for its sufferers (Walker and Fincham 2011). They could also be the result of the medicalization of problems previously understood as aspects of character and disposition, or of innovations in clinical therapies including the availability of new drugs (Fee 2000). Indeed, all of these contributory causes could themselves be consequences of the expansion of the idea of individualism to include an expectation of mental health for everyone, beginning with adults and then expanding to include children (Meyer 1987). That so much effort has been devoted to explaining the benefits to employers of addressing mental health problems might indicate the same process of institutional response to the challenges posed by individualism already discussed in earlier chapters (Harder et al. 2014). Once again, employers, and particularly capitalist employers, are required to be guardians of individualism, particularly under neoliberalism.

Far from individualism causing mental illness in the way that Ehrenberg and Verhaeghe imply, mental illness would therefore owe its treatment, its profile and indeed its origins to individualism. The connection between mental illness and neoliberalism would then be a spurious one, caused by their separate relationships to the growth of individualism. If the evidence for a causal connection between neoliberalism and mental illness really is in such short supply, why are so many writers and commentators convinced of it? One possibility is that they are generalizing from their own experience as successful professionals.2 A British academic, for example, would have no difficulty in validating their proposition about increased performance anxiety by drawing on their own experience and the experiences of their acquaintances. Academics and writers are not necessarily representative of other occupations, however. We might also need to be wary of generalizing the experiences of European writers who have been embroiled in local struggles to preserve employment rights (for example, employment protection and limitations on the intrusion of work into family life) which do not exist elsewhere. In such cases, a public intellectual might well make arguments against the intrusion of Anglo-Saxon neoliberalism, without too much regard for the detailed correspondence between their arguments and the evidence base.

Now there are a great deal of data from many different countries on workplace stress: is increasing stress the obvious proof of the impossible and damaging demands of individualism? Finding evidence of a long-term increase in workplace stress is not easy and, even if it could be established, such an increase might have other causes. Moreover, it is possible that, as with mental illness, individualism has been implicated in the increased attention given to stress rather than in the underlying phenomenon (Meyer and Bromley 2013; Wainwright and Calnan 2002).3 The institutionalization of stress looks very like the kind of institutional responses to the expansion of individualism we have encountered so many times in recent chapters, for example considerable effort has been devoted to arguing that capitalism has a vested interest in reducing stress. Thus, bodies like the Health and Safety Executive and the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service in the UK, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the American Institute of Stress in the USA, and the International Labour Organization have presented the elimination of stress as an organizational imperative, citing working days lost to stress and associated mental illnesses and making estimates of the cost of lost productivity, income and medical treatment.

Other sources of the data needed to support the idea that neoliberal individualism causes mental illness might include international evidence of the relationship between social capital and mental health (Brown and Harris 1978) or the relationship between inequality and mental illness (Wilkinson et al. 2011). In the case of the former, it could be argued that the replacement of collective agreements by an individualized employment rights framework is tantamount to the loss of the social networks and rich associational life theorized as social capital. The fact that, when faced with problems at work, employees still seek out the support of trade unions could be adduced as supporting evidence (Bagguley 2013, Barmes 2015). Evidence that inequality is associated with mental illness (amongst other health problems) might be offered as support for the suggestion that the imposition of moral responsibility on the individual for their success or failure creates psychological and emotional problems.

A third source of evidence is worth considering at greater length. This is the research drawn from many different countries that has established the range of health effects, including mental illness, caused by bullying and harassment in the workplace. The sheer number of studies, and the robust nature of many of their findings, suggests that the links between bullying and harassment and depression, anxiety and other disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, are now accepted (Einarsen et al. 2010). What these studies have not established is that the ill-treatment which psychologists label as bullying and harassment has increased because of individualism. There are no robust time-series data on which we can establish an upward trend and, even if one could be established, the incidence of bullying recorded in representative studies of working populations with sound research methods is frequently in single figures (Fevre et al. 2010). Such low figures hardly suggest that bullying and harassment have made a major contribution to the ill health caused by neoliberal individualism.

Perhaps, as with stress, individualism has not caused bullying and harassment but simply drawn our attention to it and made its eradication the responsibility of the employer? Encouraged by the psychologists who have catalogued its ill-effects, including the loss of organizational efficiency occasioned by the psychological effects of bullying and harassment, employers have accepted bullying and harassment as their latest test in the effort to prove themselves as the guardians of individualism.4 We might therefore conclude that Verhaeghe’s (2014) analysis was too superficial when he posited an association between bullying and harassment and individualism caused by anxious employees taking out their frustrations on vulnerable colleagues.

I want to suggest that the connections between bullying and harassment, individualism and neoliberalism run much deeper than is usually assumed. I have argued throughout this book that the original stimulus to the apparently limitless expansion of individualism was sentimental sense-making. Sentimental beliefs about what human life could be like made the extension of self-determination possible, and cognitive individualism had the task of adapting institutions to make these beliefs a reality. Whether this cognitive individualism was in tune with the American ideology of the nineteenth century, twentieth-century British socialism or twenty-first century neoliberalism, it was prone to over-claim how much the institutions could offer. To avoid over-reach, institutions might endeavour to take care to reduce their aspirations of sentimental individualism to a scale that would be achievable.

Cognitive individualism’s treatment of human dignity is a good example of this more restrained approach. If injuries to human dignity are defined as the kind of interpersonal behaviour which brings to mind a parallel with the behaviour of schoolchildren, organizations are excused the much more difficult job of attending to the injuries that they have directly caused. Bringing the concepts of workplace bullying and harassment into wide circulation has helped to reduce the concept of human dignity so that it can be addressed with the (weak) regulation of interpersonal relations, organizational policies and procedures and its achievement monitored and audited with employee surveys.

As we saw in the previous chapter, this need not prevent employers presenting their policies on bullying as designed to achieve the much greater aim of protecting dignity at work. Nevertheless, we can predict that what employers and psychologists recognize as bullying and harassment will fall far short of what people feel is an assault on their dignity (cf. Wainwright and Calnan 2002). Evidence for such a shortfall might lend support to the idea that one link between neoliberalism and mental health problems can be located in the disappointed expectations of employees. In this case, so far as they have (sole or contributory) workplace causes, depression, anxiety and other conditions are caused by not having enough individualism rather than too much.

This is not to say that these employees recognize their employers have been party to ramping up expectations and then failing to satisfy them. As we will see, it is entirely feasible that employees experience the disappointment of their expectations as the consequence of their own, personal failings. This might be particularly likely when employers are insistent that they have all the policies and procedures required to ensure dignity at work. Self-blame would be a further aggravating factor: employees are told to expect to keep their dignity at work, but when they suffer indignities they add shame and guilt to a situation that may already be conducive to emotional and psychological problems.

INSUFFICIENT INDIVIDUALISM

What, if any, is the evidence for the idea that neoliberalism creates new risks to mental health because it offers to satisfy ambitions for individualism that it cannot possibly fulfil? From the foregoing analysis, it is clear that data on bullying and harassment are ultimately of little help in investigating the idea of a link between mental illness and disappointed expectations of individualism. Largely by confining aspirations to improved interpersonal relations between rank-and-file employees, these concepts have served to put a limit on the expansion of individualism. By definition, they can tell us nothing of what the organizations have been unable to deliver. We require a different conceptualization of human dignity which does not reduce it to the subject matter of psychology. To make a start, we need a neutral concept like ‘ill-treatment’ that takes dignity out of the schoolyard and leaves behind the notion that injuries to dignity in the workplace necessarily take the form of interpersonal conflicts (Fevre et al. 2012). How are we to operationalize ‘ill-treatment’ in order to find out how common it is, and compare its frequency to that of bullying and harassment?

In fact, the psychologists who were researching workplace bullying made a major contribution towards solving this problem, albeit that this might not have been their intention. In order to identify the kinds of behaviour that occurred during bullying, they developed a questionnaire for counting the frequency of ‘negative acts’ in the workplace (Einarsen et al. 2010). In choosing these ‘negative acts’, they seemed to have been mainly thinking about just the kind of ill-treatment that would injure dignity and signal a failure to deliver on individualism.

Since they were chosen to indicate what bullying might entail, we would expect some overlap between the negative acts and bullying but we would also expect the measures of ill-treatment to be more common. In the pilot survey (with over a thousand employees) for the BWBS, respondents were asked the questions in the ‘negative acts’ questionnaire as well as one of the standard bullying questions. Most of the people who had experienced this ill-treatment did not think they had suffered bullying (Fevre et al. 2012). Research by psychologists had usually shown that less than half of those who experienced a negative act reported bullying (Fevre et al. 2010), but in the BWBS the overlap was even smaller. For only 2 of the 22 negative acts did more than 4 out of 10 think they had been bullied and in most cases the proportion was much smaller.

The BWBS pilot was followed up with ‘cognitive testing’ designed to refine the psychologists’ questions about ‘negative acts’, in order to produce 21 questions which would be valid and reliable measures of ill-treatment in the workplace (Fevre et al. 2010). The data from the main BWBS were analysed using component factor analysis which distributed the 21 items into three types of ill-treatment (Fevre et al. 2012). The first type was labelled ‘unreasonable treatment’ and included these eight items: (1) someone withholding information which affects your performance, (2) pressure from someone else to do work below your level of competence, (3) having your views and opinions ignored, (4) someone continually checking up on you or your work when it is not necessary, (5) pressure from someone else not to claim something which by right you are entitled to, (6) being given an unmanageable workload or impossible deadlines, (7) your employer not following proper procedures and (8) being treated unfairly compared to others in your workplace.

The second type of ill-treatment produced by the factor analysis, termed ‘incivility and disrespect’, covered: (9) being humiliated or ridiculed in connection with your work, (10) gossip and rumours being spread about you or having allegations made against you, (11) being insulted or having offensive remarks made about you, (12) being treated in a disrespectful or rude way, (13) people excluding you from their group, (14) hints or signals from others that you should quit your job, (15) persistent criticism of your work or performance which is unfair, (16) teasing, mocking, sarcasm or jokes which go too far, (17) being shouted at or someone losing their temper with you, (18) intimidating behaviour from people at work and (19) feeling threatened in any way while at work.

The final type was ‘violence’, consisting of (20) actual physical violence at work and (21) injury in some way as a result of violence or aggression at work. The researchers were surprised to find that the incidence of violence (6 per cent) was comparable to the incidence of workplace bullying in more representative studies with good sampling and data collection methods. Nearly all of those who experienced violence in the workplace also experienced both of the other types of ill-treatment (Fevre et al. 2012). The others types were far more frequent than violence: half of the British workforce had some experience of unreasonable treatment and 2 out of every 5 workers had experienced incivility and disrespect. A total of one in three had experienced a combination of unreasonable treatment and incivility and disrespect. Within each of these types, many respondents experienced several different types of ill-treatment. Amongst those who experienced unreasonable treatment (items 1–8), 1 in 4 had suffered three or more different kinds of unreasonable treatment, and 1 in 10 reported five or more kinds. Within the group which reported ‘incivility or disrespect’, 1 in 4 experienced three or more types of this behaviour and it was, once more, about 1 in 10 who reported five or more varieties of incivility or disrespect.

These data may allow us to measure the gap between what employees feel is an assault on their dignity and what the employers and the psychologists see as bullying and harassment. However, if we are going to use this data to investigate the connection between individualism and mental illness, we will need to establish that the gap really does refer to disappointed expectations. We will also need to establish that these wider measures of injured dignity have anything to do with mental illness. Finally, we will need to investigate whether these data shed any light on speculative explanations of the mechanisms involved in the relationship between neoliberalism, individualism and mental illness, including the possibly corrosive effects of ersatz morality and the role of performance anxiety and self-blame.

BROKEN PROMISES AND MENTAL HEALTH

Carefully reading the 21 items listed above suggests that many of them ought to be very effective indicators of employees’ disappointments with individualism in the workplace. If employees take individualism seriously, they have a right to expect to have a workload they can manage and to be asked to do what they are good at with the information they need to perform well. But it is not just unreasonable treatment that indicates the broken promises of individualism since employees who are treated as individuals will not expect to suffer gratuitous incivility and disrespect. In both cases (and even more so when there is violence), these measures of ill-treatment suggest that employees’ fate seems to be out of their hands. Without the autonomy promised by individualism, there is nothing they can do to make work rewarding or, perhaps, even bearable.

On face value, then, it would be hard to consider any of the 21 counts of ill-treatment as anything other than obstacles to self-determination and infringements on individualism. Moreover, many of these measures, and particularly those of unreasonable treatment, take us further from the psychologists’ analogy with the behaviour of the schoolyard and closer to the specification of the organization’s direct responsibility for injuries to dignity (Bolton 2007; Sayer 2007). Moving beyond a psychological view of injuries to individualism widens the area of normal organizational activities that are affected beyond the inter-personal relations of rank-and-file employees. It now covers many areas of organizational life that employers may be uncomfortable dealing with, or incapable of addressing, through cognitive individualism. This is well justified theoretically: instead of reducing the aspirations of sentimental individualism to objectives that can comfortably be encompassed with familiar organizational responses, they are presented as fundamental challenges to organizational claims to value individualism. Stating the organization’s position on inappropriate joking is one thing, but making the connection between injuries to individualism and pay or performance management opens up whole new areas of organizational activity for consideration. In some cases, we may even find that the organizational monopoly over the division of labour is shown to be incompatible with individualism.

The BWBS showed that 1 in 2 British employees had experienced one or more injuries to individualism in the previous two years (and 1 in 5 had experienced frequent and multiple frustrations of individualism). At first glance, it seems difficult to imagine how the idea of employers as the guardians of individualism could survive but, thus far, we are relying on our own interpretation of the ill-treatment measures. Was it the case that employees saw these measures differently, perhaps in the limited terms of bullying and harassment which reduce injuries to individualism to transgressions that organizations can accommodate without undermining their employees’ belief that individualism is the key to organizational success?

In the BWBS, about a quarter of those experiencing unreasonable treatment and/or incivility and disrespect had experience of three or more types of ill-treatment. This ‘troubled minority’ were asked follow-up questions about the most serious ill-treatment they had suffered, for example workplace violence (Fevre et al. 2012). These questions included the type of person responsible for the ill-treatment: were they a client or a customer, a subordinate, a peer or a manager? Most unreasonable treatment originated with managers and supervisors, and even in incivility and disrespect, where co-workers and customers or clients were more frequently blamed, managers and supervisors were the most important. Violence was the only type of ill-treatment for which managers and supervisors did not receive most of the blame.

These results suggest that employees were more likely to see ill-treatment in terms of organizational failure than interpersonal problems like bullying. To confirm this, we simply need to revisit the list of the different kinds of ill-treatment with the knowledge that each of them was more likely to originate with a manager or supervisor. If you were on the receiving end of each of these forms of ill-treatment, what might you conclude about your employer’s commitment to dignity at work? What might you conclude about the way your employer was selecting, training and managing your manager? Might you conclude that your manager had been told that, whatever the rhetorical commitment made by the organization, dignity and respect were superfluous to organizational objectives (Foster and Scott 2015)?

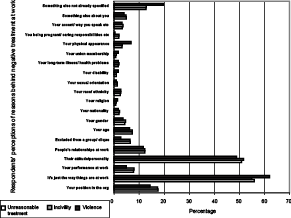

The troubled minority were also given a list from which they could choose as many reasons for their ill-treatment as they thought appropriate. The two most popular reasons were the same for violence, incivility and disrespect and unreasonable treatment. In all three cases, the majority reported ‘it’s just the way things are at work’ and around a half cited ‘the attitude or personality of the other person’. The only other options that attracted more than one in ten responses were ‘your position in the organization’ and ‘people’s relationships at work’. Figure 13.1 summarizes the bivariate analyses of all causes of ill-treatment.

Figure 13.1 The causes of ill-treatment in the British Workplace Behaviour Survey

A brief review of the results for violence and injury will show how these results can inform our discussion. Roughly half of the employees who experienced violence and injury said it was a consequence of the ‘attitude or personality of the other person’ involved (all data from Fevre et al. 2012). We might imagine that this suggested they understood the causes of violence as lying well outside the direct responsibility of their employers and that a commitment to dignity at work, for example a ‘zero-tolerance’ approach to violence which promised the employer would prosecute all cases of violence against employees, was enough to preserve their reputation as guardians of individualism. Yet, two-thirds of those who had experienced violence and injury – including some of those who also blamed another person’s attitude or personality – said this was ‘just the way things are at work’.

It becomes easier to understand these results when we learn that many of the employees who experienced workplace violence were employed in personal service occupations where low-level violence from clients might be a frequent occurrence. As well as police officers, paramedics and firefighters, it was care assistants and nurses working in residential care settings or private households who reported that their experience of violence was just the way things were where they worked. While this might suggest a pattern of repeated, less serious assaults, it also suggested that zero-tolerance approaches which promised prosecution of any assault were so impracticable as to have fallen into disrepute.

The rhetorical commitment to zero-tolerance cost the employer nothing, whereas employees – and especially those who said it was their role that exposed them to violence – were aware that the risk of violence could only be reduced by significant change in the division of labour, including job redesign and higher staffing levels. In this case, there seemed to be strict limits on how much individualism they could expect of their employer. This conclusion was writ large in the 1 in 8 cases where employees agreed that a cause of the violence they had experienced was their ‘position in the organization’. In other words, it really had not mattered who filled their role since they would have received the same treatment. Moreover, since it was the employer who created these positions they had indirect responsibility for their exposure to violence. It might be expected that if the ill-treatment measures were better understood in terms of interpersonal problems like bullying, this would be particularly obvious in the case of incivility and disrespect. In fact, the results for this type of ill-treatment varied little from the other two types.

As before, most respondents said that this was just the way things were in their workplace. Indeed, this was given as the more common reason than the attitude or personality of another person for most types of incivility and disrespect, with the exception of shouting, rudeness, intimidation and threats. It is quite salutary that exclusion by other employees and humiliation, gossip and teasing were all more likely to be traced back to the nature of the workplace, than to the interpersonal explanations that are usually associated with bullying. Exclusion and gossip were also associated with another minor reason for ill-treatment: relationships at work. This reason was cited more frequently for incivility and disrespect than it was for unreasonable treatment, nevertheless it hardly figured as a reason for insults and rudeness (Fevre et al. 2012).

The final evidence that the measures of ill-treatment are a valid and reliable way of measuring employees’ perceptions of their employers’ inability to deliver on their promises of individualism comes from MV analysis of all the factors that might be correlated with each measure. Excluding the two measures of violence and injury, the strongest correlations across all of the remaining measures were found to be with the three general questions on individualism described in Chapter 12: whether respondents thought that people always came second to the organization, whether they had to compromise their principles at work and whether their employer treated them as individuals. In Chapter 12, we used these questions to show how much consent and resistance might have been excited by the long process of rolling out cognitive individualism within organizations. Moreover, they are such a strong predictor of ill-treatment that they can also be used to represent important characteristics of workplaces that are hard to capture in a survey of employees.5 However, here we use them to confirm that most measures of ill-treatment also record a broken promise of individualism.

Employees who thought people were not treated as individuals in their workplace were at the greatest risk of unreasonable treatment across the board. There were other strong predictors of unreasonable treatment – such as having less control over one’s work or having a disability – but none were as strong as this direct measure of an employer’s commitment to individualism. The other general question about not having to compromise your principles at work was just as significant a risk factor for unreasonable treatment as having less control and stronger than having a disability. Taken together, the three general questions about individualism were as good at predicting the risks of incivility and disrespect as they were for unreasonable treatment. At least two of the questions were a risk for every type of incivility and disrespect in the MV models for each of the 11 measures. Earlier in this chapter, we noted that Verhaeghe and others thought that forcing employees to compromise their principles in the neoliberal workplace might have a lot to do with work-related mental illness. We now know that compromising your principles is one of three general questions about individualism which were strongly correlated with the measures of ill-treatment, even when other variables were taken into account. However, we still require some less circumstantial evidence if we are to be convinced that injuries to individualism are implicated in mental illness.

ILL-TREATMENT AND MENTAL ILLNESS

The first data of interest are derived from the questions that respondents to the Fair Treatment survey were asked about the impact of seven of the 21 measures of ill-treatment. The seven were selected to represent unreasonable treatment, incivility and disrespect, and violence. They were: pressure from someone else to do work below your level of competence, your employer not following proper procedures, being given an unmanageable workload or impossible deadlines, being insulted or having offensive remarks made about you, being treated in a disrespectful or rude way, being humiliated or ridiculed in connection with your work, and actual physical violence at work (Fevre et al. 2013). Although the size of the effect was not as high as for the Fair Treatment question about bullying and harassment,6 around 1 in 8 employees who had experienced one of these forms of ill-treatment suffered ‘severe psychological effects’. In addition, at least 1 in 5 said they had suffered ‘moderate psychological effects’ for every 1 of the 7 measures bar the last one: actual violence.

This last, surprising result was the only case in which there was no statistically significant difference between the employees who had experienced ill-treatment and those who had not. In all of the other six types of ill-treatment, there was a clear statistical difference in the likelihood of both moderate and severe psychological effects. However, the fact that the result for violence did not achieve statistical significance is interesting when we remember that violence was the one area in which the three general questions about individualism were not strongly correlated with ill-treatment in MV analysis. Since the general questions about individualism were so strongly predictive of unreasonable treatment and incivility and respect, there is a suggestion here that ill-treatment is most likely to lead to psychological problems when it is most clearly and unambiguously an indicator of broken promises about individualism. This perhaps brings to mind an observation made by Fleischacker when commenting on a quote from Adam Smith (see Chapter 3):

[E]ven where the material harm done is slight, an act of injustice suggests that the victim is somehow less worthy than the agent, and thereby constitutes an important symbolic harm. The anger that boils out of the passage indeed captures wonderfully how we feel when another person seems to imagine that we ‘may be sacrificed at any time, to his conveniency or his humour’. (Fleischacker 2013: 488)

These reflections might give pause to anyone tempted to dismiss these results as simply confirming what we already know about the extent of the psychological harm associated with bullying and harassment. Between a third and a half of those experiencing these much more common forms of ill-treatment than bullying suffered moderate or severe psychological effects. If we take the most common type of ill-treatment – that of being given an impossible deadline or unmanageable workload – slightly more than 1 in 10 British workers experienced psychological harm from this one type of ill-treatment, perhaps four times as many workers as might suffer harm from bullying.

Other relevant data which come from further MV analysis of the BWBS showed impressive correlations between several types of ill-treatment and respondents’ declarations that they had psychological or emotional problems (Fevre et al. 2012, 2013). We will, however, postpone detailed consideration of these data until later in the chapter and consider further data about work and the workplace instead. From what we have learnt so far, we would expect the most concerted efforts to persuade employees of employers’ commitment to neoliberalism to take place in organizations which expect high levels of commitment from their employees. These are two sides of the same neoliberal coin: in return for safeguarding individualism and, indeed, because they safeguard individualism, organizations benefit from higher productivity.

The data on ill-treatment confirm what has sometimes been suggested in studies of workplace bullying, namely that some of the characteristics of high-commitment workplaces successfully predict ill-treatment even with statistical controls for other variables. In MV analysis of the BWBS, the predictors of ill-treatment included working at a fast pace and larger organizations. For example, feeling that the pace of work was too intense increased people’s exposure to ill-treatment by 56 per cent. MV analysis also showed that it was those employees who would be most exposed to the expectations of high commitment who were more likely to report ill-treatment.

In MV analysis of the BWBS, permanent staff with managerial responsibilities were more likely to experience both unreasonable treatment and workplace violence. Better-paid employees were more likely to experience unreasonable treatment (Fevre et al. 2012). As Anthony (1977) noted 40 years ago, managers in particular have provided the model for high-commitment relations in the workplace.7 They have therefore been amongst those most exposed to the disappointment of expectations, and we would expect them to report some of the ill-treatment that indicates broken promises, perhaps particularly unreasonable treatment. Once more, this underlines the departure from the expectations of Verhaeghe (2014) and many researchers of bullying8 that it is mostly the weak and the vulnerable who are affected. This is perhaps much less the case for injuries to individualism than it is in bullying and harassment.

A further predictor of ill-treatment (most unreasonable treatment and several types of incivility and disrespect) was reduced control, and it was more strongly associated with unreasonable treatment, incivility and disrespect and violence than almost any other factor (Fevre et al. 2012). The key issue to note here is that the analysis also included a measure of low control which was not associated with any of the 21 measures of ill-treatment. It was the feeling of being deprived of autonomy, rather than never possessing it, that went with ill-treatment, and it is of course the former rather than the latter that we would associate with an affront to individualism and, particularly, with the disappointment of employees who had expected they were to have a more rewarding relationship with their work.

Some evidence of the effect of broken promises also came from MV analysis in which change in the nature of work and work intensification were shown to be risk factors for unreasonable treatment, although not for incivility and disrespect (Fevre et al. 2012). As with reduced control, employers who change the nature and pace of work put in jeopardy the work they have done to persuade their employees to see them as the guardians of individualism. Qualitative research confirms that a great deal of planning and operational attention is required to retain this reputation while also making significant changes to the nature and pace of work (Fevre et al. 2012). Without this effort, employees may begin to doubt that their individual contribution is valued and was perhaps ever valued. This need not imply, however, that they blame their employer.

The qualitative research undertaken in the companion case studies to the BWBS chronicled the stories of employees trying to respond to the pressures of high-commitment workplaces and pushing themselves to breaking point (Fevre et al. 2012; Foster and Scott 2015). They felt that their work had become unmanageable, their deadlines impossible, that what was happening to them was unfair and irrational, that there was a more reasonable way to achieve the organization’s goals but that nobody was listening to them. If they resisted, they put themselves in line for personal attacks, especially from those senior staff who were passing on the pressures of the high-commitment workplace (Barmes 2015). Sometimes these managers told them they were not up to the job and should leave before things became even more unpleasant for them.

Some of the workers who chose to stay, or had nowhere else to go, blamed their managers (often in very bitter language) for what had happened to them (Fevre et al. 2012). They usually ascribed character faults to their managers which would explain why the managers were unable to uphold the organization’s commitment to individualism. If there were colleagues who were obviously in the same position, this might lead to incivility and disrespect aimed at the managers, and even to what psychologists term ‘upward bullying’.

If there were no colleagues to hold responsible, or it was implausible that the manager’s character faults were to blame, employees who suffered ill-treatment could only conclude that their managers were pursuing the goals of the organization and that it was they, the employees, who were undermining these goals. They responded to the pressure and criticism by working harder and faster, and this often produced what their general practitioner or occupational health professional might eventually label as stress. With or without the label, employees in this position would often push themselves to the point at which they concluded that they were incapable of living up to the opportunities that they had been offered. Their employer was committed to individualism, certainly, but this had only exposed the employees’ failings.

This qualitative research suggests that Verhaeghe (2014) and others are right to suggest that neoliberal individualism is implicated in the relationship between mental illness and the workplace. The cognitive individualism of the neoliberal workplace demands that the individual be judged according to the criteria the employer sets to measure their contribution. When employees fall short, there is no place to hide. Cognitive individualism puts all of the onus on the individuals’ demonstration of their worth and it repeatedly demands new evidence of this (with every financial quarter, new project, new manager, new organizational initiative). Everything comes down to how you, on your own, handle the demands of work and this turns out to be an invitation to self-destruction.

In effect, the self-destruction of employees is the safety valve which allows neoliberalism to keep its promise of safeguarding individualism. If employees can respond to the demands that are placed on them, then the promise remains intact: their employer has simply given them an opportunity for self-development and to demonstrate flexibility and they have altered their habits and feelings about work accordingly. However, if they cannot respond – even if nobody could respond – the promise is preserved by blaming the employee rather than the employer. For this to work most effectively, the employee must accept the blame they are offered and in this way they are led into putting their own mental health at risk.

I have already noted that employees may sometimes support each other by sharing their uncomplimentary (and often reprehensible) views about the character of the person, usually a manager, they feel is failing to treat them as an individual. Given that roughly half of the British working population has some recent experience of injuries to individualism, this raises the question of why they do not turn from blaming their managers to identifying their private problems as a public issue. Yet, few of them are in a position to understand that there are so many other employees with whom to make common cause. This privilege is reserved for social researchers, worker representatives and those trade union members who read their trade union’s literature. The rest of the workforce (a sizeable majority) have no way of knowing that there is a public issue at stake here and they only have their own families to tell them that it is not their fault and they are not on their own (Barmes 2015). Friends and family can confirm they are being badly treated, even bullied, but it is almost impossible for them to see this private problem as a public issue common not just to one organization but in the wider world of work (Fevre et al. 2012).

Despite what they might have assumed prior to suffering ill-treatment, employees cannot rid themselves of the feeling that they must be failing to meet the rational expectations of their employer, and this often produces an existential crisis that may lead to psychological and emotional problems. The risk of internalizing the problems created by organizations promising cognitive individualism they cannot deliver is common to everyone including managers. In MV analysis, managers were more likely to report unreasonable treatment (and violence), but we know from Chapter 12 that managers were also more likely to hold onto the idea that individualism was safe in their workplace. I also mentioned earlier in the chapter that employees with disabilities were more likely to experience ill-treatment and it is to detailed consideration of this group of employees that we now turn.

COGNITIVE INDIVIDUALISM AND DISABILITY

While not taking away from the way ill-treatment can trigger illnesses or make them worse, there is also a great deal of MV evidence from the BWBS to show that those who already had disabilities (including long-standing psychological conditions)9 were more likely to suffer a variety of different forms of ill-treatment. Some of this treatment occurred in high-commitment organizations but the ill-treatment of employees with disabilities also illustrates some other ways in which employees pay for the broken promises of cognitive individualism. The British research discussed in this chapter shows that employing someone with a disability – especially certain disabilities (see below) – is a crucial test of an employer’s ability to deliver on these promises and that, when they fail to deliver, the blame is invariably assigned to the employee (Fevre et al. 2012, 2013). Usually, this involves denying that the disability has anything to do with the individual’s needs or capacities, and often this means that the employer will deny the employee has a disability at all.

Here, we are no longer always investigating the effect of change occasioned by the employer but rather the way the requirements of illness or impairment set tests for employers which they regularly fail. The test may be as simple as allowing an employee to keep a hospital appointment but, if the employer decides they cannot accommodate this, a similar situation is produced as when employees experience reduced control or work intensification. The promise to recognize people as individuals, to take seriously what they say and what their requirements are, is broken. In the BWBS and its associated qualitative case studies, employers were seen to fail these tests every day when they made decisions about sick leave, employees returning to work after sickness absence, the management of ongoing conditions, and ‘reasonable adjustments’ to work and the workplace required by UK legislation (Fevre et al. 2012; Foster and Scott 2015; also see Foster 2007). The Fair Treatment at Work survey also showed that employees with disabilities were twice as likely as other employees to experience a range of employment rights problems. In bivariate analysis, they were especially likely to report problems with sick leave or pay but also with holidays, rest breaks, number of hours or days worked, pay, contracts, complaints procedures, grievance procedures, health and safety, and retirement (Fevre et al. 2009).

The more common way of conceptualizing the idea of a broken promise in respect of employees with disabilities is provided by the social model of disability (Oliver 1983, 1990, 2003; also see Barnes and Mercer 2004). In the model, an impairment or a condition only becomes a handicap when society provides an environment (for example, the workplace) and structures social action (for example, work) in such a way that those with an impairment or a condition are put at a disadvantage (Fevre et al. 2013). The social construction of disability is one and the same as the failure of an employer to accommodate disability as one of the many requirements of treating employees as individuals.

Since most employees do not know the social model, they often blame themselves for their disadvantages (for example, their ill-treatment). This is especially likely in the case of mental illness where people may be less likely to recognize they are ill and even less likely to recognize they have a disability. In this connection, it is salutary to note that MV analysis of the BWBS shows that, of all the possible types of disability, it was a physical disability that was the more weakly associated with ill-treatment (Fevre et al. 2013).10 That it was only significant for two of the 21 items, even at the lowest (90 per cent) level of significance, suggests that employers are better able to stick to their promises when their employees have an obvious physical disability like an impairment of sight, hearing or mobility. Of course, this only applies to those employers who hire such workers in the first place. Since their disabilities are so obvious, it makes them the easiest targets for discrimination at the recruitment stage and, in the UK at least, this discrimination contributes to an increasing gap in the employment rates of employees with and without disabilities (Fevre et al. 2013).

We now move on to consider other categories of employees where their disability would necessarily be less visible at recruitment and may not have been disclosed to employers. Because they are more likely to involve later-onset illnesses than physical disability, these same categories of disability are also more likely to be acquired after recruitment. A measure of the total impact of having a disability across the 21 multivariate models applied to the BWBS data set showed that for those with the obvious physical disabilities the likelihood of experiencing any ill-treatment at work was increased by 15 per cent. For those with a learning difficulty, psychological or emotional condition, the likelihood of experiencing any ill-treatment at work was increased by 177 per cent. For those with other health problems (including life-threatening conditions) like cancer, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart disease, pulmonary conditions, asthma and digestive or bowel disorders, the likelihood of ill-treatment was increased by 102 per cent.

MV analysis also allowed better specification of which categories of disability were associated with each kind of ill-treatment. Employees with psychological problems and learning difficulties were four times as likely to be treated unfairly, and employees with other health problems were seven times more likely to say they had been pressured not to claim something (perhaps sick leave or sick pay) to which they were entitled and three times more likely to say somebody was continually checking up on them. Those with other health problems and psychological conditions were three times more likely to say their employer had not followed proper procedures (Fevre et al. 2012).

It is certain that some of the association recorded in the BWBS between ill-treatment and psychological problems was further proof that ill-treatment had effects on employees’ mental health. However, for reasons discussed elsewhere, these correlations also confirm that employees are more likely to suffer ill-treatment if they have a pre-existing psychological condition (Fevre et al. 2013). More fine-grained MV analysis of the BWBS tells us more about the way that different types of ill-treatment were associated with different categories of disability. Specifically, those in the psychological category were the most likely to experience nine types of ill-treatment, whereas those in the category of other health problems were the most likely to experience six types of ill-treatment (Fevre et al. 2013).

There was very little overlap between the types of ill-treatment associated with these two categories. Apart from being treated unfairly, and finding their employer not following proper procedures (one of the few types which was also associated with other health conditions), most ill-treatment of those in the psychological category took the form of incivility and disrespect. The ill-treatment of those with other health problems was more widely spread. While this might lend some support to the idea that some of the associations for the psychological category were the effects of ill-treatment on mental health,11 the particular patterns of ill-treatment associated with the different categories could as well be a result of tailoring the ill-treatment to the disability or, rather, of the nuanced way in which disability is signalled in the workplace. For example, those in the category of psychological disabilities were much more likely to be subject to gossip and socially excluded.

In common with other employees, respondents with disabilities were more likely to blame managers for their ill-treatment: four in every nine said their managers were responsible followed by clients and customers (28 per cent) with co-workers a distant third (18 per cent).12 They were also asked what they felt to be the root causes of this ill-treatment (Fevre et al. 2013). We might imagine that having a disability and experiencing persistent criticism, being shouted at, or even threats or violence at work, would lead to a conclusion that this ill-treatment was related to the impairment, but this was very unusual. Only 11 out of 284 respondents thought their impairment had anything to do with their ill-treatment and only 25 out of 284 felt that their ill-treatment was related to long-term illness or other health problems. Just like the majority of other types of workers, those with disabilities were most likely to give the reason for their ill-treatment as just the way things were at work, their position in the organization or their performance at work. Of course, this means that very few employees were recognizing their ill-treatment as discrimination which is not permitted under UK law (Fevre et al. 2012, 2013).

This is one more proof (see Chapter 11) of how ineffective the equality legislation delivered as part of the ambitious programme of cognitive individualism has proved itself. However, the whole story of the fate of workers with a disability, for example as captured in the social model, is proof of the general tendency of cognitive individualism to lead organizations to claim far more than they can ever deliver. People with disabilities offer employers the hardest test of their sincerity because they cannot be treated as the normal – meaning largely invariant – worker who employers have in mind when they make their promise to treat everyone they employ as an individual (Foster and Wass 2013). They can make good on this promise as long as those individuals do not actually behave like individuals. People with disabilities are the most likely to do this and they will always provide one of the key tests of how much individualism a society can claim to have achieved. They are the embodiment of the ideal of individualism which organizations cannot live up to and because of this they cannot escape punishment. Unfortunately, they are not alone: in MV analysis of the BWBS, being gay, lesbian or bisexual increased the overall risk of ill-treatment by 56 per cent.

LGB employees constitute another group whose existence puts the promises of individualism to the test. As with employees with less visible disabilities, it is hard for employers to screen them out with discriminatory recruitment practices,13 yet their ill-treatment within the workplace amounts to discrimination. Moreover, as with employees with disabilities, LGB employees do not recognize that they suffer discrimination but find instead that their hopes about the freedoms that individualism ought to permit are unlikely to be borne out by their experience of the workplace (Einarsdottir et al. 2015a). They may be affected by this even where they have not disclosed their sexuality, indeed this may be why they do not disclose. Voluntary disclosure suggests a freedom they may not feel they have in the workplace, for example it implies that their idea of who they are as gay men or lesbian women will not collide with a stereotype (Einarsdottir et al. 2015b). However, like almost everyone else who suffers ill-treatment, LGBs rarely reach conclusions about the broken promises of individualism because, failing to see any obvious prejudice to resist, they resolve to adapt themselves to the situation. As with many employees with disabilities, they try hard to make themselves less like individuals to fit into a workplace that promised them something more (Einarsdottir et al. 2015a). In fact, it is a paper-thin individualism they are being offered – one that is highly gendered and one with concealed traps, many of which lead to ill-treatment (Einarsdottir et al. 2015b).

CONCLUSION

There is an alternative to employees taking on the burden of keeping cognitive individualism afloat by being less individual, making themselves ill or finding another job. They might choose to build a social movement which could turn their private problems into public issues. This movement would expose the broken promises and their attendant discriminations and, by demanding radical changes in work, and particularly the division of labour, would stimulate a new politics. The catalogue of ill-treatment shows us how high ambitions could be for individualism in the workplace, but how could such a social movement come about? From the previous two chapters, we know that, in Britain at least, it is only a minority that are sceptical about their employer’s ability to deliver genuine individualism. However, we know from those chapters how important personal experience is to building scepticism. If this works for the experience of employment rights problems, unfair treatment and discrimination, sexual harassment, bullying and harassment, might it not also apply to ill-treatment in the workplace?

Trade unions provide one possible source of the leadership for such a movement but we have heard in previous chapters about the burdens they allow to accumulate on the worker representatives in workplaces which already have a union presence. The way in which the trade unions treat the worker representatives who deal with mounting caseloads of workers who have experienced ill-treatment gives little cause for confidence in their ability to assume leadership. We will return to these questions in the final chapter but first we need to deal with some other unexamined questions about the relationship between capitalism and individualism – questions that we have, up to this point, managed to keep at bay with the idea of neoliberalism.