| CHAPTER 8 |

|

My alarm woke me at 2 AM. I roused Walid and, to my surprise, he rose without resisting. With help from Baba and Abdi, we loaded Lachmar and L’beyya quickly. Since it felt like we’d said our real good-byes the night before, our final farewells were brief. I promised Abdi I’d deliver the letters he wrote and thanked him again for everything, then shook Baba’s hand and said, “May Allah watch over you.”

“Safe travels,” he replied. “Peace be upon you.”

“And upon you, too,” I answered.

Walid grunted, slapped L’beyya lightly with his stick, and we set off toward the south. I’d thought we were going to rendezvous with our new caravan before departing, but something about Walid’s manner implied that we were hitting the trail for real, not casually sauntering to a meeting place. I wanted to know what was going on.

“Where’s the caravan?” I asked.

“Just up ahead,” Walid said. “We’ll catch it in a minute.”

Too reminiscent of what I’d heard so many times on the way to the mines, Walid’s words conjured a dread-filled premonition that we were in for a replay of the trip north, ever chasing the caravan and mostly traveling without it. Should I stop and refuse to leave Taoudenni until we were with a caravan, I asked myself, even if it meant waiting a few more days? But what if Walid was right this time? My head spun as I weighed the possible options and outcomes, knowing this was a crucial decision, feeling pressured to make it quickly, and having no actionable intelligence, just hopes and fears.

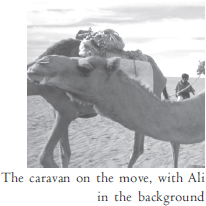

Before I could make up my mind, a man who was seeing off another caravan came walking in our direction. He told Walid that ours hadn’t left yet, and if we waited it’d probably pass by in a few minutes. So we stopped where we were and, true to the man’s word, a shadowy string of twenty-six camels soon shuffled up in the darkness. At its head was an azalai named (what else?) Baba; taking up the rear was his helper, a young boy named Ali. We all exchanged greetings as Walid and I fell in alongside them, I awash with relief.

The waning moon hovered in the east, the constellations shimmered brightly against the inky blackness of a perfectly clear sky. My turban was wrapped around my face for warmth; walking took the chill from my body. As we moved through the night, Baba sang lilting Koranic chants, one after the next, to keep the evil spirits at bay.

Images of the past few days flashed through my mind. What I’d discovered at Taoudenni was as unexpected as it had been profound. Each memory was a jewel without price and, like a beggar who stumbles upon a treasure chest, admiring them one after another made me drunk with exuberance. I had to deliberately slow my strides if I didn’t want to leave the caravan behind.

After a couple of hours, we mounted up and rode into the morning. At dawn, by silent agreement, everyone slid from their animals and took to their feet once again. It was time to pray. Walid handed me our camels’ rope and, to my astonishment, Baba asked me to lead his caravan as well. While the three nomads knelt in the sand, I marched on with a grass rope over each of my shoulders, pulling twenty-eight camels behind me.

Now that it was light out, I was able to get my first glimpse of my new companions. With a patchy beard over his sunken cheeks, eyes bulging from deep sockets, and a nearly shaved scalp, Baba looked like a well-tanned Hare Krishna on a hunger strike. A shredded blue sweater covered his ragged blue boubou. I guessed he was in his mid-fifties, but later learned he was thirty-three, the same age as me. Ali, on the other hand, was fifteen but looked no older than eight. His face was full, his ears stuck out to the side, and his gleaming, squarish teeth were a little too big for his mouth. Over his boubou, he wore a navy-blue hooded sweatshirt with a zipper in the front. It was his second season working on a salt caravan. Walid teased that he was the littlest azalai in the Sahara, and Ali scowled silently at the gibe. He could be playful and credulous—like the child he resembled—but turned touchy and spiteful when his inferiority complex got the best of him.

With the night behind us and prayers out of the way, it was teatime. Baba untied the portable brazier that was lashed to his camel; Walid leapt atop L’beyya, fished the teapot out of his bag, and filled it with water and tea leaves. I traded Baba the caravan for the brazier, which Ali and I packed with camel dung we picked up on the trail. The two of us worked as a team, heating the water, brewing the tea, mixing the sugar, and passing glasses to everyone else, careful not to spill a drop while we strode over the sand. Though of course the azalai could have managed just fine without me, I was already feeling more useful than I had at virtually any point on the trip to Taoudenni. Having led the caravan during prayer and contributed to our morning’s caffeine fix, I was making their lives just a little bit easier and was glad to prove myself an asset—however small—so early in our journey south. Traveling with twenty-eight camels lacked some of the majesty of traveling with seventy-five, but the large caravan had an impersonal, almost corporate feel to it. This was like a family-run operation and gave me a chance to have a more hands-on experience. I was happy with the trade. And, soon enough, I’d have the best of both.

Traversing a plain of red sand, we followed a trail trampled by countless camels, crisscrossed by the textured ruts left by truck tires. Before, I might have seen this juxtaposition as symbolic of the coming death of the caravans; with what I now knew, it seemed like an apt metaphor for the harmonious coexistence of camels and trucks, and the system that worked for their mutual survival. Up ahead, another caravan came into view, snaking up a rounded ridge, the slabs of salt slung over the camels’ backs reflecting the light of the rising sun like pieces of moon. Seeing us, the caravan slowed, allowing us to catch up to it.

It was a little smaller than ours—twenty camels led by two azalai. One of them was dressed in a dark blue bathrobe that hung below his knees, as though he’d just stepped outside to grab the morning paper. It was cinched around his waist with a wide leather ammunition belt, like an empty bandolier. His name was Hamid. His cousin, Dah, dressed more traditionally, wearing a dark sweater over his boubou. Both were twenty-one years old, and each had just a faint trace of a mustache with no beard to speak of. After the greetings finally came to an end, Dah pulled out a bag of peanuts and offered everyone a handful. To reciprocate, I passed some biscuits around. The food sealed a tacit agreement that we’d stick together from here on.

As the morning wore on and we neared our tenth hour on the trail, a heavy languor settled over the caravan. Unlike the trip north when the sun was often at our backs, it now blazed directly into our faces, persuading me to close my eyes. We rode in weary silence, smothered by heat, swayed into semi-consciousness by the hypnotic motion of the camels, until a sudden burst of chaos jarred us to attention.

With no warning or cause, two camels went berserk, jerking their leads away from the camels in front of them, breaking the ranks, bucking and rearing like broncos stung by bees. Cargo pads, bags, and bars of salt flew from their backs and crashed to the ground. In an instant the five azalai and I were off our mounts. Walid ordered me to the front of the caravan and told me to hold the ropes of all the lead camels to prevent a general mutiny, while he and the others surrounded the renegades. Walid darted in front of the bigger of the two beasts, reaching for the rope that was still attached to its mouth. The camel leapt and flailed, kicked and roared—towering tall on its hind legs, its front feet thrashing the air, it was terrifying and ridiculous, looking like some bizarre creature out of a fairy tale that might shoot flames from its mouth. With its strength and clumsiness it could surely do some serious damage to a man whether or not it intended to.

Walid, however, was unflapped. Once he seized the camel’s rope, he didn’t let go. Trying not to spook it further, he waited patiently for his moment, then pulled its head toward the ground. The others then rushed in like wolves and forced the camel to its knees while Walid pressed its head pressed against the sand. He held it there until the camel calmed down, while the others went to wrestle with the second animal. Seeing its cohort subdued, it lost heart for the struggle and offered little resistance. I continued to hold the caravan in place while the azalai loaded the fallen goods back atop the camels that had flung them off. A couple of the salt bars had split upon impact, and had to be bound together with rope before they could be carried.

While watching the azalai quell the camel rebellion, I’d desperately wanted to take photographs of these cool headed nomads—one of them in a bathrobe—wrangling with crazed camels like they were in some kind of Saharan rodeo. But I’d been given a job, and couldn’t do it and take pictures at the same time. Torn between my roles as an observer of the caravan and a participant in it, the temptation to leave my post and pick up my camera was tremendous. In my gut, however, I knew my duty to the caravan had to come first; aside from enhancing our overall welfare, it was the only way I could hope to be accepted as anything more than a total outsider.

Before starting out again, Baba took the big camel, the one that started all the trouble, and moved it to the front of the line, tying it to the tail of his own camel on a very short lead, like the caravan version of sending a kid to the principal’s office. Though there were occasional outbursts among the ranks in the days that followed, they were very rare and very minor. Contrary to their reputations for nastiness and obstinance, for spitting and other forms of rudeness, the camels were generally compliant and well behaved, especially considering what was demanded of them day after day.

We continued on across the sand, now orange in the full glare of the sun. Mirages flowed like cool, sparkling streams. I realized that this was the last time in my life I’d ever see this place; I had no illusions about returning someday in the future.

We reached camp—a flat hollow among low, sharply cut dunes of rose-colored sand flecked with black—a little after 3 PM. The azalai couched their camels and began unloading salt immediately. When Walid and I had our bags off Lachmar and L’beyya, we went over to help. If I’d been expecting Walid to patiently demonstrate the proper technique for taking salt off a camel’s back, I’d have been disappointed. There was simply no time for instruction. The azalai worked as though unloading the camels quickly was a matter of saving lives, so I just jumped in and lent a hand, observing, learning, and doing simultaneously, hoping I didn’t screw anything up. At first the others tried to shoo me away, afraid I’d break the precious bars, and I understood. After all, this was their income, and they’d risked their lives for it. But unloading salt was definitely not rocket science, or even cooking. With the camels prone, one man took hold of a bar on one side of a camel while another man grabbed its sister bar; they were lifted off simultaneously and carried a few feet behind the camel, where they were propped against each other at an angle, so they stood up forming an A-frame. The same was done with the second set of bars, which were rested up against the first set. It had to be done with care, especially since each weighed more than eighty pounds, but it was pretty simple. I knew that if I stayed on the sidelines, it’d only create the perception that I was useless and establish a routine in which I was left out. Walid, remembering his promise to include me in all things azalai, worked with me. By the time the last camel had been freed from its burden, the azalai conceded that I was fit to help, and even congratulated me on doing a good job. The camels were set to graze upon the fodder cached here days earlier.

Shortly before sunset, I wandered off to take some pictures of the dunes. After about ten minutes of meandering around the sand, it occurred to me that even though I spent much of my days in silence, this was the longest I’d been alone since leaving Timbuktu. It was profoundly liberating; for the first time in weeks, I could fly around that internal space that only expands when no one else is around; a place where I need to spend time regularly in order to stay sane. Loath to leave it before I had to, I stayed out until it was nearly dark.

By the time I returned, Walid had started dinner. Another caravan had arrived during my absence, with thirty-four camels and three azalai. Though I didn’t meet them then, we would all depart and travel together from then on.

After eating, Walid told me to set my alarm for 2 AM. I lay down at 7:30 PM and fell asleep quickly. The next thing I knew, I was being shaken awake and told to get moving. It was 9:30 PM. As usual, Walid’s estimates of time were a little less than precise.

Due to the time it took to load all the camels, it was nearly two hours before we actually left camp. When we did, we made a number of false starts. Baba and the leader of the new caravan, named Sidali, struggled in the total darkness to find the channel that would take us through the dunes in the right direction. The camels were led one way, then the opposite way, so the camel train doubled back on itself in a U. Baba swept the weak beam of his flashlight across the sand, with inconclusive results. At last Walid, who had kept his counsel to himself until this point, strode to the head of the line and kept on going, with a clipped, confident pace. I was right behind him and, even though the others had the benefit of the light, I trusted Walid’s instincts more than anyone else’s eyes. Apparently they did, too, for they followed along behind us. Aside from not needing a light, I believed it would be beneath Walid to use one.

Just as I finished that thought, as though to deliberately shatter my idealization of him, he asked Baba if he could borrow the flashlight. But he only needed to see in order to fix his flip-flop; the piece that ran between his toes had broken. Once he assessed the damage, he clicked the light off and put it in his pocket, took a handful of grass, lit it on fire, then melted the severed plastic back together.

About five minutes later, Baba questioned Walid’s route, pointing to Sidali, who was beginning to set out on a different angle. “Look,” Walid said, snapping the light on and pointing it at the ground for a few seconds, just long enough to prove his point. We were walking directly atop a trail of camel prints left by the last caravan to pass this way.

Emerging from the dunes onto the open flats, we were met with a blast of frigid wind. Walking kept me just warm enough, but when I mounted Lachmar and sat motionless and high, the breeze drilled through my clothes and my body. My bones felt brittle, my flesh frozen. For a few moments, I weighed the merits of putting on my sweater, which I’d been using as extra saddle padding, but there was little to debate—only whether or not I’d gone nuts, since I couldn’t believe it could be this cold in the Sahara. Even the sweater wasn’t enough. Reluctantly accepting whatever price my ass would pay, I unfolded the blanket I was sitting on and wrapped it around myself, as the other azalai had done. My legs, however, unlike theirs, were too long to tuck under the folds of the blanket. My bare feet dangled, fully exposed, going numb. I pressed them into the soft fur on Lachmar’s chest and neck, trying to warm them. I periodically checked my watch—after weeks of praying for the moment the sun would go down, I couldn’t believe I was desperate to see it rise! By the time it did, my water bottle had iced over.

Confronted with a new form of suffering, my thoughts turned to death. I no longer feared it as I had when embarking on the caravan, not because I was any more confident I’d make it back alive, but because I felt that if I did die, I’d have no regrets. My experiences at the mines had made everything I’d endured thus far, and almost anything I could endure, worth it. Since there were few ways in which I’d die instantly, I imagined that if I became injured or ill I’d have at least a few hours in which to bring some closure to my life. I would first write a letter to my parents, then I’d write about Taoudenni, so others could glimpse what I had seen there. I’d leave instructions for it to be read at my funeral as my last farewell, as the last thing I had brought back from the world to family and friends. Thinking about this scenario, which was admittedly a little grandiose, I saw that greater than my fear of death was my fear of dying for something stupid—now that I didn’t have to worry about that, I could accept a hypothetical demise more readily.

I slipped off Lachmar about an hour before sunrise to get the blood moving in my feet. As on the previous morning, the others paused to pray when light began to fill the sky, and I became captain of the caravan—only this time, with our additional companions having hitched their animals to ours, I single-handedly led a train of eighty-two camels into the dawn. I looked at myself as if from above, and starting laughing, touched by the image, as beautiful as it was absurd, of a man living out his farthest-fetched dreams.

When the azalai caught up to me, the morning tea was started and I met the members of the new caravan. Sidali, its leader, was forty-two, with a shock of wild black hair, a heavy black beard and mustache, a prominent nose, and creased mahogany skin. Over a soiled tan djellaba, he wore a long, dark plaid trench coat that might have been from London Fog’s mid-1970s line. His twenty-year-old son, Bakar, was equally fashionable, sporting a gray wool suit jacket over a brown, blue, and beige djellaba, plus yellow pants and a teal turban. Omar, the third member of their team, was Sidali’s twenty-one-year-old nephew; judging by his outfit, he was like their poor relation—his standard blue boubou was torn and frayed around the edges. While Sidali and Bakar welcomed me with warmth and respect, Omar immediately demanded that I give him my lighter, which Ali had used to start the tea. When I laughed at his brashness and said no, he asked me to give him some food.

Since it was teatime, I conceded, passing some biscuits around to everyone, and setting a problematic precedent. Aside from millet and rice, which were only eaten at camp, the azalai carried virtually no other food (though Dah had some peanuts, he didn’t have many), meaning they had nothing to eat during the long hours on the trail. Walid and I, of course, had biscuits, peanuts, and dates, but just enough for us to indulge a little bit every day; if we regularly shared with seven other people, our supplies would’ve been quickly exhausted.

As Walid had promised, we only had time to eat one plate of rice a day. It felt like one plate too many. Since the camel meat we’d bought at the mines had to be carried in a bag, it hadn’t dried thoroughly and had gone foul, though it was hard to tell when doused with our rancid, sunaged goat butter—now going on four weeks old. And as always, the rice was sprinkled with generous helpings of sand. It reminded me of the joke Woody Allen recounts in Annie Hall, the one in which two women complain about a restaurant: “This food is terrible.” “And such small portions!” Though I’d force myself to eat my entire serving purely to keep up my strength, it only sated my hunger for a short time; I relied on our snack food to quell the gnawing in my belly during the long nights and days on the march and didn’t want to give it all away.

My instincts for self-preservation conflicted with my ethical ideals, especially in a Muslim context, where food is treated as communal property. After all, I was traveling with these people and felt like there was a moral imperative to share what I had. But driven by hunger and the fear of future hunger, I tried to rationalize my way around it. These men, I told myself, were accustomed to their Spartan ways, and if I wasn’t there they’d be fine surviving on their meager diet with no extras. Moreover, by sharing with everyone, the food would be spread so thinly among us that no one would ever get enough to even dent his hunger. Still, a part of me was unconvinced, so that evening I asked Walid what he thought about this dilemma. His answer was unequivocal.

“It’s your food,” he said, “and you need it. They know it, but will ask for it anyway. You don’t have to give them anything.”

Even with Walid’s blessing, I felt uncomfortable about eating in front of the others and not offering to share. At night this was no problem, thanks to the darkness; when I got hungry during the day, I’d hide a small bag of peanuts and dates in my lap and shuttle them to my mouth a few at a time, as discreetly as possible. Every so often I’d share with everyone else.

For the most part the others obeyed an unwritten code: Since I didn’t flaunt it, they didn’t ask for it. Baba and Omar, however, were the exceptions, and they didn’t limit their requests to food. Over the next week, they demanded everything from peanuts to my sunglasses to my shirt. Sometimes they cajoled, other times they pouted. At camp each afternoon, when Walid dished up a couple handfuls of peanuts and dates to eat along with our dorno, Baba inevitably appeared, knowing he wouldn’t be turned away; finally Walid, of his own volition, pretended we had eaten the last of them—fooling even me into believing him—so Baba would stop expecting to be fed. But he still expected me to supply him with black tea. Every afternoon, without fail, he’d approach, imploring, “Michael, Lipton? Lipton?” Since I had plenty, I gave it to him freely, and it turned into a joke; I’d pull out a tea bag and hand it to him before he even said a word. Omar so persistently asked me for my lighter that I finally gave it to him, just to shut him up. I had a spare one anyway.

I felt I had to deal delicately with Omar. He was energetic and charismatic and could be quite charming. But he was capricious and would turn suddenly, becoming obnoxiously dismissive or mildly menacing. He reminded me of one of those classic teenage types, one of whom I imagine everyone knew back in high school: They’re popular, athletic, and good looking, usually in a Nordic kind of way. They treat you like a buddy one day and a loser the next, drawing you in then putting you down. This was similar to the game Omar played, keeping me ever off balance—such as the time he asked me to take his picture, then aggressively demanded that I pay him for the privilege after I did (he calmed down only when I reminded him about the lighter I gave him). But there was one big difference between Omar and those high school kids, and it was me—back in high school, as an insecure teenager, I’d really wanted those jerks to like me. In the desert, I wanted to be able to like Omar but didn’t really care how he felt about me—though I figured it was important that he not dislike me too much.

For the most part, though, I felt very much at ease among the azalai. Sidali and Bakar were funny and kind. Dah and Hamid were quiet and usually kept to themselves in camp. Of the two, I became particularly friendly with Hamid, who came to me every day for medical treatment for his hands, which were covered with lacerations he’d acquired when harvesting the bales of tall desert grasses carried and cached for camel fodder; the edges of the grasses were so sharp, they’d cut into his skin like razors when he yanked them from the ground. Seeing me apply New-Skin to Hamid, Baba, naturally, wanted some for his own cracked fingers. Since I had plenty of the stuff to spare, I happily doled it out, but convinced him that his wounds weren’t bad enough to require the Band-Aids I gave Hamid. Though his perpetual pleas for tea and food were occasionally annoying, Baba, too, was easy to get along with, and I had a sense that, in a pinch, he’d have my back. He gracefully tolerated my imitations of him: I’d mimic the call he often uttered while driving his caravan—which was a wordless chant similar to Tarzan’s trademark cry—and I’d ape the way he shouted to his partner, a high-pitched “Yeh, Aliiiiiiiiiiiiiiii!” The other azalai loved these impersonations, and would ask me repeatedly to “do Baba, do Baba,” after which they’d break into hysterical laughter.

We arrived at our second camp in the full heat of midafternoon after fifteen hours on the trail. We unloaded the camels, made tea and dorno, then I collapsed for an hour or so under the shade of our blanket shelter. After dinner, I passed out again, getting in about three hours of sleep before being woken around 10 PM to start packing for the evening march. This time I kept my socks handy.

Though it was easier on the camels to march through the cold nights than to face the afternoon heat, I found it even more demanding than traveling during the day. With a late-rising moon near the end of its cycle, the desert was usually pitch dark. Unable to see the ground before me, I slammed my feet into countless rocks, which would’ve resulted in many broken toes had my sandal soles been a few millimeters shorter. If I had to go to the bathroom while riding, I’d slide off Lachmar and step to the side as the caravan continued on, all sight of it quickly absorbed by the night. At times, when it would get far ahead, I feared I’d wander off course, completely alone, while trying to catch up to it. I’d only find it again thanks to the call-and-response system Walid and I had practiced since our first day on the trail; I would shout, an azalai at the back of the caravan would shout back, and I would follow the sound, moving as quickly as I could, until I could hear the soft shuffling of hundreds of camel feet and the exotic melody of Baba’s chants. Fortunately I’d become deft at mounting a moving camel, and could do so in the dark without disrupting the camel train.

Most challenging of all, by 2 or 3 AM, having snuck in only a few hours of sleep at camp, it was nearly impossible to stay awake. Exhaustion posed no problems for the azalai; having grown up in the saddle, they could slumber for hours at a time while we rode. Often they slept sitting upright; other times, they’d lie down and curl up on their blankets; the only ones who had to stay partially alert were those at the front of the line. But every time I’d start to drift off, I’d wake with the terrifying jolt of my body righting itself just as I was about to topple off my camel. The scare would be enough to keep me awake for a few minutes, but I was so tired that sleep soon seduced me back into its sweet caress. Again, I’d be jarred awake moments before tumbling from my perch. I tried lying down like the azalai did, but couldn’t; my head and feet hung down over the slopes of Lachmar’s hump, and the camel rocked like a rowboat on rough seas. Aware that falling would result in serious injury, I had no choice but to fend off sleep with all my will. After flirting seriously with it for a while, as with a woman I found irresistible but knew I’d best keep away from, I’d muster my resolve and renounce it.

I devised activities, physical and mental, to help me stay awake. I took the loose rope dangling in front of me and challenged myself to tie different kinds of knots in total darkness, pretending I’d gone blind. I bit my dirty nails and the cuticles around them. I sang. I made lists: the best meals I ever ate, letting my mind travel from Cairo to the Loire Valley to Houston Street; the worst meals I ever ate: the festival of guts on the way to Araouane; the dinner I’d had a few hours earlier. I tried to run through Descartes’s ontological argument for the existence of God, which, as a college philosophy student, I would review in my head while I was having sex, since I didn’t know any baseball statistics. (In the desert, I couldn’t remember it all—obviously I hadn’t gone over it enough times back in school.) Sometimes I would remember particular scenes from my past, trying to recall them in supersharp detail, down to textures, smells, and shadows, unsure how many of those details my mind was inventing. One night, in groggy delirium, my mind wandered back to the night of a concert I’d seen when I was a teenager, and I made the terrible mistake of listing all the Billy Joel songs I could think of—for days afterward, I was cursed with verses of “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” playing in my head, and came to rue the day I ever heard the names Brenda and Eddie.

When nothing worked and sleep seeped through me like a drug, I would get off and walk. At least if I fell over then, I’d be much closer to the ground.

Between camps we never, ever stopped and hardly ever slowed, moving anywhere from fifteen to nineteen hours at a stretch. That men did this was impressive; what the camels did was astonishing. Many of them carried more than four hundred pounds. None of them drank a single drop of water for twelve days.

We reached our next camp in mid afternoon. It was at the small well called Ounane, the one at the base of a low hill at which Walid, Baba, and I had briefly stopped on our way north. Our arrival was followed by a frenzy of action—unloading the camels, then rushing to fill our guerbas. Since it would take hours to water all the camels and they could survive without it, we only drew enough for ourselves. My job was to scoop water from the trough into the inner tubes, and as usual, I didn’t do it fast enough to meet azalai standards. As Walid and Baba hauled up the water, Ali knelt by the side of the trough, “coaching” me with all the compassion of a drill sergeant. For the first time in his camel-driving career, Ali wasn’t the low man on the totem pole. Finally there was someone he could boss around, and he never missed an opportunity to do so. At first, thinking he was trying to tell me how I could best help out with whatever job was at hand, I followed his instructions. But after a day or two, when I realized he was simply exercising the little bit of power that he had and that what he told me to do was sometimes ill advised, I felt free to ignore him. As I poured water into the guerbas at the well, Ali peppered me with criticism and finally, to demonstrate what a poor job I was doing, took the metal bowl from my hands. I bristled, then after a minute of standing dumbly, stalked back to where Walid and I had left our bags and started a fire and a pot of green tea.

Meanwhile, Sidali, Bakar, and Omar were busy branding some of their younger camels. The camels seemed to sense something unpleasant was about to happen to them and resisted couching on command. Together, the three azalai would muscle one to the ground and lash its front feet close together so it couldn’t get back up. Omar held the camel in as much of a headlock as can be managed on a creature with a yardlong neck. Bakar pressed the weight of his body against the front of the camel’s hump. Sidali drew his knife and cut into the camel’s hide on its front flank, deeply enough to draw blood and, ultimately, create a scar.

Massive gray clouds swept in from the west, like an armada of warships steaming across open ocean. The leading edge sprayed us with a gentle drizzle, which suddenly exploded into a raging deluge. Rain poured in torrents. Gusts of wind ripped through camp, battering us with waves of airborne sand. Hail the size of grapes fell like shrapnel, chasing us under our blankets to protect us from their stinging, bruising impact. Lightning shot from the clouds. Thunder echoed across the sky. Parked as we were in a vast, open plain, we were in one of worst possible places to sit out an electrical storm. Of the many ways I’d imagined dying in the Sahara, being struck by lightning wasn’t one. I was glad that the camels were so tall, thinking they might act as lightning rods.

In fifteen minutes, the heart of the storm had passed, though rain fell intermittently into the night. The azalai decided we would lay over the next day to make sure the salt bars and the leather tie straps had a chance to dry completely and regain their integrity before being transported. I greeted the news gladly.

Our things had been so thoroughly drenched that nothing had dried by the time dinner was over. Wearing my damp clothing, I headed for a clammy night’s sleep, slipping between the folds of my dirty, soggy blanket that reeked like wet camel—an odor not unlike wet dog, but much more gamey.

By morning the clouds were gone. Blankets and clothing and salt all dried quickly. With nowhere to go, we enjoyed a day of leisure. I took out my map of Mali, which actually showed the main wells between Timbuktu and Taoudenni, and upon which I’d been marking the general location of our camps each night. Omar and Sidali were intrigued, so I showed them the route we were following. Since they couldn’t read, I listed off and pointed to the wells, while they nodded in excited recognition, thrilled that the features of their isolated world had been published on a map. I explained how to estimate distances using the kilometer scale, then gave them the map; they spread their fingers between Timbuktu and Araouane and Taoudenni, then compared it with the scale, then debated how many kilometers actually lay between each place.

When they tired of that, Sidali decided it was time for some personal grooming. He lay on his stomach in the sand, still dressed in his trench coat. Bakar pulled out a pair of old metal scissors, crouched by his father’s head, and proceeded to crop Sidali’s hair nearly down to the scalp. Walid criticized the unevenness of the cut, so took the scissors and finished the job. He then asked to borrow my Swiss army knife and used its small scissors to prune Sidali’s beard. When Sidali was cleaned up to everyone’s satisfaction, Walid trimmed his own beard, then used a razor blade to shave his cheeks—no water, no soap, just steel on skin. Omar borrowed the blade afterward, and shaved himself. I felt like I was hanging out with a bunch of guys playing beauty parlor in the middle of the desert.

The late-morning heat rose quickly, so I set up a blanket for shelter, which Walid and I crawled under for a mid day nap. We woke after a couple of hours and I read for a while, now Kipling’s Kim. I restitched my shirt, which had split along the seams between the sleeves and the shoulders, and sewed up a few tears in my pants, then helped Walid with dinner and tea. I was able to sneak in another two hours of sleep before being wakened and told to start packing. It was only 8 PM.

The next five days and nights were a grueling exercise in endurance. Each evening we broke camp between eight and nine, meaning that every day I was only able to get an hour or two of sleep in the afternoon and an hour or two after an increasingly disgusting dinner. We walked and rode and walked and rode for what seemed like forever, through freezing nights, into blistering days. Though I had many years of wilderness experience behind me and had often pushed myself beyond my perceived limitations, nothing I had ever done came close to comparing to the endless rigors of traveling with the caravan. Walid had been right—it was far more challenging than traveling on our own schedule. When not on the move, I closed my eyes at every opportunity and, regardless of how hot it was, who was talking around me, or whether or not I was even feeling tired at that moment, I could throw my internal circuit breaker and shut myself down as fast as if I’d injected sodium pentathol.

There were times when thinking about the rest of the day, the rest of the journey, became overwhelming. As I fought to put one weary foot in front of the other, to bear the sun staring me in the face, or to stay seated atop Lachmar when ready to drop from exhaustion, it was impossible to imagine making it to the next camp, let alone all the way back to Timbuktu. In order to slip from beneath the crushing weight of future thoughts, I adopted a technique of focusing solely on the moment I was living. In itself, removed from the time line that stretched forward and backward from the present, no single moment was that bad. Perhaps I was walking under a starry sky at 2 AM; forgetting that we’d already been on the move for five hours, and probably had another twelve to go, I could find pleasure in being exactly where I was, right then. Maybe because I was so tired it was easy to achieve an altered state of consciousness; with a little focus I was able to travel through the desert as though in a temporal bubble, totally immersed in the present, as though past and future no longer existed. It became something of a spiritual practice—the transcendence of suffering by meditating on “the now”—and I nearly signed on wholeheartedly to the clichéd mantra of “Live the moment.” Then I realized that, while I spent half my time doing just that, I spent the other half of the time escaping the moment—distracting myself with mind games, reading while I rode—and that that was just as crucial to maintaining my sanity.

At times, when all else failed and I felt myself succumbing to exhaustion, doubting that I had it in me to reach the next camp, I’d gain strength by thinking about my grandmother.

She had grown up in Romania, and was sixteen years old when that country’s fascist regime, complicit with the Nazis, ordered the deportation—or death—of the entire Jewish populations of Bessarabia and Bukovina in 1941. In many ways a trial run for the mass exterminations that followed in other parts of Europe, Jews were rounded up in towns and villages and sent east on forced marches into an area of Ukraine between the Dniester and Bug Rivers, known as Transnistria. Rather than leading the deportees directly to the Transnistrian camps, German and Romanian soldiers herded them in circuitous routes. My grandmother and her family marched, at the prodding of Nazi rifles, every day for more than two months. The roads were knee-deep in mud. Typhus raged unchecked through the convoys. No food was provided, so the Jews scavenged what they could from fields they passed or traded diamonds for onions with local peasants. Regardless of the weather, they slept in the open—and they were walking straight into the Ukrainian winter with little more than the summer clothes they had on their backs when they first left their homes. My grandmother’s group only stopped when waist-high snowdrifts made further travel impossible. While some deportees were shot by the soldiers for lagging behind, most were simply left to die. Of the estimated 190,000 Jews who lived in the provinces of Bessarabia and Bukovina in the spring of 1941, some 65,000 died before ever crossing the River Dniester—some in orchestrated massacres, many more while in transit. Another seventy-five thousand perished on the roads and in the camps of Transnistria. If my grandmother could survive such a nightmarish trek as a teenage girl, I thought, surely I could meet any challenges this caravan posed.

Surprisingly, I wasn’t always miserable. Though the tough times were barely bearable, at other times I felt energetic, even inspired. Without fail, sunrise filled me with new life, with relief, with humor. As the morning tea was made and we could see each other again, the azalai and I reveled in one another’s company like men who’d been separated and spent a lonely night traversing some mythic Underworld. We talked and joked—once, spying a piece of wood that had fallen from another caravan, I went to pick it up. It would burn hotter and longer than dung. But little Ali snuck up behind me, trying to steal the prize for himself. We raced, and when I beat him, I held the fat stick over my head in triumph while everyone else hooted with laugher—except Ali.

Our eighth day out from Taoudenni was first day of the Muslim month of Shawwal—the holiday of Eid-al-Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan. Being a time of great celebration across the Islamic world, during which prayers are offered, charity is given, families visit one another, and feasts are held, I wondered if the azalai would do anything special for it. Just because they hadn’t observed the fast, I thought, was no reason not to take advantage of a good excuse to party. But the day passed just like all the others, as though there was nothing special about it.

Two nights later, we left camp at nine. After about four hours, Walid and I, whose camels were hitched together, veered away from the caravan, striking off from it an angle. At first I thought he wanted to give us a little bit more space, but the distance between us kept growing, so I asked what was going on.

“Araouane is this way,” he said.

“Well, why are they going the other way? Don’t they know the route?”

“Sure they do, but they aren’t going through Araouane.”

“What do you mean? Aren’t we all traveling back to Timbuktu together?”

“No. They’re not going to Timbuktu. They’re going home first, and Araouane is out of their way.” I wouldn’t learn exactly why this was for two more days.

I was speechless. Parting ways with the caravan so suddenly, with no warning, was like having something stolen out of my hands. I couldn’t believe that Walid hadn’t mentioned anything about it in advance, and I prickled inside. But worst of all, I hadn’t even had a chance to say good-bye to any of the azalai. I felt like something important had been left incomplete.

I was so thrown by the abrupt shift in my reality that I hardly realized how incredible it was that, in the middle of a pitch-dark featureless plain with even the stars obscured by haze, Walid had known when and in which direction to turn in order to lead us to Araouane.

After an hour or so of juggling a jumble of emotions, from anger to loss to anxiety, I let them all drop and left them behind me in the sand. I’d had an incredible experience with the azalai, and this shining truth easily burned off the disappointment of leaving them sooner than I’d expected. Besides, thanks to what the trials of caravan life had taught me, I knew in my bones, not just my brain, that there was little worth getting upset about as long as I was alive and well. And, though I didn’t know it then, leaving the others would allow us to enter an entirely different, even more exotic kind of nomadic world.

Walid and I rode on and on, into what would be our longest day on the trail of the entire journey.

Dawn broke beautifully. The sun poured like molten brass between platinum-fingered clouds. The ivory sand was drenched with pinks and blues and yellows absorbed from the sky. I heard the twitter of a birdsong for the first time in weeks. The entire world seemed at peace with itself. And I was no exception. I felt clean inside, utterly content, and gave heartfelt thanks for all that I had in that moment, and in my life. It was an appropriate time to do so, since it was Thanksgiving morning.

Though I was half a world away from family and friends, nibbling on peanuts rather than gorging on turkey, riding forever on a camel rather than resting on a couch, I found myself in a more natural state of gratitude than I ever have when celebrating the holiday at home. With nothing but the essentials for survival, surrounded by nothing but desert, I felt like a rich man. I had my memories of Taoudenni, and of the azalai. I had a trusty camel beneath me. I was sharing the day with a man whose life and language were so different than my own, yet with whom the seeds of friendship had blossomed in the common ground of our humanity. Most of all, I was grateful that my body and mind had been able to adapt to the insane regimen of caravan life.

This attitude stayed with me throughout the day. I felt strong, like I’d crossed a threshold into a new level of endurance, where no amount of strain could break my body or my spirit. And it served me well: except for two brief stops for tea and dorno, we traveled on until sunset, a total of twenty-two hours on the march.

For the effort, we earned ourselves a full night of sleep, though for the reward I was really looking forward to, I’d have to wait one more day.